Abstract

Background

β-blockers may protect against catecholaminergic myocardial injury in critically ill patients. Long-term β-blocker users are known to have lower lactate concentrations and favorable sepsis outcomes. However, the effects of β1-selective and nonselective β-blockers on sepsis outcomes have not been compared. This study was conducted to investigate the impacts of different β-blocker classes on the mortality rate in septic patients.

Methods

We retrospectively screened 2678 patients admitted to the medical or surgical intensive care unit (ICU) between December 2015 and July 2017. Data from patients who met the Sepsis-3 criteria at ICU admission were included in the analysis. Premorbid β-blocker exposure was defined as the prescription of any β-blocker for at least 1 month. Bisoprolol, metoprolol, and atenolol were classified as β1-selective β-blockers, and others were classified as nonselective β-blockers. All patients were followed for 28 days or until death.

Results

Among 1262 septic patients, 209 (16.6%) patients were long-term β-blocker users. Patients with premorbid β-blocker exposure had lower heart rates, initial lactate concentrations, and ICU mortality. After adjustment for disease severity, comorbidities, blood pressure, heart rate, and laboratory data, reduced ICU mortality was associated with premorbid β1-selective [adjusted hazard ratio, 0.40; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.18–0.92; P = 0.030], but not non-selective β-blocker use.

Conclusion

Premorbid β1-selective, but not non-selective, β-blocker use was associated with improved mortality in septic patients. This finding supports the protective effect of β1-selective β-blockers in septic patients. Prospective studies are needed to confirm it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis, defined as organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection [1], is a leading cause of death in the intensive care unit (ICU). Despite significant advances in intensive care medicine, septic shock mortality rates remain high, ranging from 40 to 50% [1]. Hence, more knowledge of the pathophysiology of sepsis is needed. Overwhelming inflammation, arterial vasodilation, and hypovolemia are the main components of the early phase of sepsis. Sympathetic activation is triggered to maintain systemic perfusion and oxygen delivery to vital organs. Adverse effects of catecholamine overactivation in sepsis include tachycardia-induced myocardial damage [2], inflammatory cytokine production [3], insulin resistance [4], and thrombogenicity [5]. Of note, tachycardia occurring with sepsis can increase the cardiac workload and result in myocardial oxygen consumption.

The use of β-adrenergic blockade is beneficial in patients with diverse cardiovascular diseases. In the recent decades, it has emerged as a possible treatment option in early sepsis to blunt the overwhelming adrenergic responses of cardiogenic [2, 6], metabolic [7], immunological [8], and coagulopathic [5] derangement. In animal models, β-blocker administration during sepsis appears to reduce the heart rate (HR) and adrenergic activation [9]. In a prospective study, esmolol use permitted the maintenance of target HRs within the range of 80–94 bpm, increased stroke volumes, and improved 28-day survival in septic patients [10]. An observational study revealed that patients with sepsis who had been prescribed β-blockers before admission had significantly lesser mortality [11]. Other clinical studies also suggest that premorbid β-blocker exposure has beneficial effects on sepsis outcomes [12, 13]. However, data on the effects of different types of β-blocker (β1-selective and non-selective) on sepsis outcomes are scarce. This study was conducted to investigate the impacts of premorbid β1-selective and non-selective β-blocker use on sepsis outcomes using data from a single medical center. We hypothesized that mortality after sepsis development would be lesser among patients who used β-blockers, especially β1-selective β-blockers, in the premorbid period.

Materials and methods

Patient selection and data collection

This retrospective single-center study was conducted with data from patients admitted to the medical or surgical ICU of the Taipei Veterans General Hospital, a tertiary medical center, between December 2015 and July 2017. Selected subjects’ medical records, including all accessible records of hospitalization, outpatient visits, prescriptions, and examinations, were reviewed. The following data were collected: (1) age, sex, and comorbidities; (2) source of infection and severity of sepsis; and (3) laboratory measurements obtained at the time of ICU admission. The arterial blood gas samples were used for determination of pH, PaO2, PaCO2, and HCO3−. PaO2/FiO2 ratio (PF ratio) was calculated as PaO2 divided by FiO2 at the time PaO2 was measured. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) scores were calculated within 24 hours after ICU admission to evaluate disease severity [14]. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was recorded by the ICU physicians upon patients admitted to our ICU. The lowest mean arterial blood pressure (BP) and highest HR within 24 h after ICU admission were recorded. The study protocol is in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and international ethical standards and was approved by the hospital’s ethics board (Num. 2017-09-018BC).

We included consecutive patients aged ≥ 18 years who were admitted to the ICU with the diagnosis of sepsis and fulfilled the Sepsis-3 criteria [1]. We considered patients who had been prescribed β-blockers for >1 month before ICU admission to be premorbid β-blocker users. We classified β-blockers as β1-selective (bisoprolol, metoprolol, atenolol) and non-selective (carvedilol, propranolol, labetalol, and acebutolol) [15].

Outcome measurement

The primary outcome was to evaluate the association between previous β-blocker prescription and all-cause mortality in the ICU. Secondary outcomes were the amount of fluid resuscitation and norepinephrine usage (defined as any dose of norepinephrine administration to keep mean BP>65 mmHg) in the first 24 h of ICU admission, lactate concentrations at 0 and 6 h after ICU admission, duration of ventilator use, and ICU stay duration. All patients were followed for 28 days or until death.

Statistical analysis

We express continuous variables as medians ± standard deviations. Student’s t test and analysis of variance were used to compare continuous variables. We express categorical values as absolute numbers with percentages; statistical comparisons were made using the chi-squared test. Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis was performed to investigate independent associations between clinical variables and ICU mortality. Variables with significant associations in the univariable analysis were adjusted for in a final multivariable regression model. To investigate the effects of premorbid β-blocker use modified by different conditions, we performed subgroup analyses with the cohort stratified by comorbidities and septic shock [1]. The survival curve was plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method with the statistical significance examined by the log-rank test. Two-tailed P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc 19.1 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics

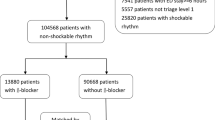

Of 2678 cases assessed, 1262 subjects fulfilled the Sepsis-3 criteria. In total, 209 (16.6%) patients were premorbid β-blocker users and 1053 patients had no previous β-blocker exposure. Of the 209 users, 137 patients took β1-selective and 72 patients took non-selective β-blockers. Figure 1 is the flowchart of patient enrollment and classification. Patient characteristics according to β-blocker use are presented in Table 1. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), cirrhosis, heart failure, arrhythmia, and coronary artery disease were more prevalent among subjects with premorbid β-blocker exposure. Hypertension and coronary artery disease were more prevalent, and liver cirrhosis was less prevalent, among β1-selective than among non-selective β-blocker users. During initial ICU admission, patients with premorbid exposure to β1-selective β-blockers had lower HRs than did those with no exposure. Disease severity, reflected by APACHE II scores, did not differ among the three groups. There was also no significant difference of hemogram, including white blood cell count (WBC), hemoglobin, platelet count, serum electrolytes, arterial blood gas, and PF ratio, between the three groups (Table 1). The missing data of each variables were reported in the Supplement Table 1.

Premorbid β-blocker use and clinical outcomes

Compared with non-users, premorbid β1-selective β-blocker users had significant lower ICU mortality. Premorbid β1-selective β-blocker use also contributed to lower percentage of norepinephrine usage and lower lactate concentrations at 0 and 6 h after ICU admission. The total amount of fluid infusion, ICU stay, and days of ventilator use did not differ among the three groups (Table 2). In univariate Cox regression analysis, reduced 28-day mortality was associated with β1-selective [hazard ratio, 0.36; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.19–0.68; P = 0.002; Table 3], but not non-selective β-blocker use. Higher HRs and lower arterial mean BP also were associated with greater ICU mortality. In the multivariate regression analysis adjusted for age, APACHE II score, hypertension, diabetes, hematological malignancy, HR, mean BP, and white blood cell count, β1-selective β-blocker exposure remained associated independently with lesser ICU mortality (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.18–0.92; P = 0.030). A Kaplan–Meier curve also showed that premorbid β1-selective β-blocker exposure was associated with better 28-day survival (log-rank P = 0.002; Fig. 2).

Subgroup findings

The results of subgroup analyses are shown in Table 4. Compared with non-use, premorbid β1-selective β-blocker use was associated with lesser ICU mortality, regardless of the presence or absence of hypertension, diabetes, ESRD, cirrhosis, heart failure, arrhythmia, coronary artery disease, cancer, and septic shock. No significant interaction between any of these variables and β1-selective β-blocker use was detected.

Discussion

In this retrospective study of data from 1262 septic patients, ICU mortality was lower among patients with premorbid β1-selective β-blocker exposure. Compared with non-use, premorbid β1-selective use was associated with lower lactate concentrations and lower percentage of norepinephrine use. Only β1-selective β-blocker use was associated with an improvement in 28-day ICU mortality. This study is the first to illustrate the effects of premorbid exposure to different types of β-blocker on short-term mortality among septic patients. The findings encourage long-term β1-selective β-blocker use, but prospective studies are needed to confirm the protective effect of such use in septic patients.

Tachycardia increases the cardiac workload and myocardial oxygen consumption. The shortening of the diastolic filling time during tachycardia decreases the stroke volume and coronary perfusion, contributing to the reduction of the ischemic threshold. Elevated HRs are associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients [16, 17], as shown in this study, and a survival benefit of β1-adrenergic selective blockade has been found in animal models [9]. By decreasing the HR, β-blockers decrease myocardial oxygen consumption and prolong the diastolic time and coronary perfusion, reducing the risk of myocardial ischemia. Several studies have shown that diastolic dysfunction is present in about half of septic patients and is a significant predictor of mortality [18]. Β-blockers have been shown to improve the diastolic function of patients with heart failure [19].

Nevertheless, the treatment of tachycardia during septic shock remains controversial. In the early phase of septic shock, tachycardia compensates for any reduction in cardiac output; HR reduction may interfere with this physiological response, reducing cardiac output and improving oxygen delivery [20]. However, tachycardia that persists after adequate resuscitation may represent sympathetic overstimulation. In patients with tachycardia (HR > 95 bpm) who received a titrated esmolol infusion with the goal of reducing the HR to 80–94 bpm, decreased HRs were offset by increased ventricular filling time and volume, ultimately resulting in increased stroke volume, which compensated for the HR decrease [10]. Similar hemodynamic effects of β1-adrenergic selective blockade by esmolol administration have been reported [21, 22]. With adequate preloading, HR reduction improves cardiac performance and efficiency [23], with the maintenance or even increase of the stroke volume. In our study, long-term β1-selective β-blocker users had significantly lower baseline HRs on ICU admission than did non-selective β-blocker users; this difference may translate into better outcomes.

Mechanisms other than HR reduction may explain the better sepsis outcomes associated with β-blocker use. The physiological response to stress includes the increased release of catecholamine. The early phase of sepsis is typically characterized by high cardiac output with decreased vascular tone, tachycardia, and impaired myocardial function. All of these factors can be associated with the elevation of the adrenergic drive to increase global and microvascular blood flow and oxygen delivery to vital organs. The direct cardiotoxic effects of catecholamine, especially norepinephrine, had been recognized for decades. A sustained increase in cardiac adrenergic drive adversely affected myocardial biology and structure phenotype in a heart failure model. The treatment of cardiac myocytes with norepinephrine caused a 60% loss of these cells [24], and the exposure of cardiac myocytes to isoproterenol had similar effects [25]. Several animal studies have demonstrated the occurrence of β1-adrenergic receptor signaling, which is considered to be more harmful to cardiac myocytes than is β2-adrenergic receptor signaling [25, 26]; these findings suggest that β1-adrenergic receptor signaling is the key mechanism for adrenergic-driven cardiotoxicity. In a clinical trial, differences in β1-adrenergic and β2-adrenergic receptor blocking doses indicated that β1adrenergic selective blockade had a better treatment effect for heart failure [27]. Previous studies have shown that activation of Na/K ATPase, which is stimulated by catecholamine, enhances glycolytic turnover and increases lactate production [28, 29]. Our findings were consistent with these results that premorbid β-blocker use had lower lactate production, probably due to the reduction of β-stimulation; and we found that only β1-selective rather than nonselective β-blocker had this effect. Hence, chronic β-blocker use may contribute to systemic protection from the catecholamine surge that occurs during sepsis.

Hyperproduction of NO by the inducible form of NO synthase (iNOS) may contribute to the hypotension and vascular hyporeactivity during septic shock [30]. Downregulation of alpha1-receptor expression also contributed to hypotension in the septic animal models [31, 32]. Esmolol infusion decreased the iNOS expression in vascular tissues [32, 33], and up-regulated mRNA expression of alpha1-receptors [32] in experimental septic shock models. In our study, we found a lower norepinephrine requirement in the β1-selective β-blocker group, which could be due to the improvement of vascular function caused by the β1-selective β-blocker. The lower vasopressor requirement also protected patients from potential side effects of high-dose catecholamine. The improved vascular function may translate to better tissue perfusion, and the lower lactate levels in the β1-selective β-blocker group.

Esmolol also improves coagulation and microvascular circulation, as determined by assessment of the sublingual microcirculatory blood flow [21]. During sepsis, physiological anticoagulation and fibrinolytic mechanisms are impaired, and the coagulation pathway shifts toward a pro-coagulant state [5]. Coagulation system dysregulation causes the dissemination of intravascular coagulation, leading to microcirculatory dysfunction and tissue production at the cellular level [17]. β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors act differently on coagulation functions. β2-adrenergic stimulation suppresses platelet aggregation [34]. β1-adrenergic stimulation inhibits fibrinolysis by reducing prostacyclin synthesis [35], whereas β2-adrenergic stimulation promotes tissue plasminogen activator release, leading to enhanced fibrinolytic activity. Thus, β1-selective β-blocker may reduce platelet activation via relative β2-adrenergic activation, and enhance fibrinolysis through increased plasminogen activation and prostacyclin synthesis [36]. In the present study, premorbid β-blocker users had lower baseline lactate levels than did non-users. After initial resuscitation, more premorbid β1-selective than non-selective β-blocker users achieved >10% lactate clearance, suggesting that β1-selective β-blockers could possibly play a role in enhancing microcirculation function by improving the pro-coagulation state during sepsis.

β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors also seem to have different actions on the immune system. Th1 cells stimulate macrophages and natural killer T cells, and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, whereas Th2 cells have the opposite actions, inhibiting macrophage activation and T cell proliferation. Th1, but not Th2, cells have β2-adrenergic receptors. Hence, β2-receptor stimulation suppresses Th1 cell activation with a relative increase in the Th2 cell response [2]. Thus, selective β1-blockade could promote β2-adrenergic pathway activation and contribute to the suppression of the pro-inflammatory status. In septic animal models, esmolol reduced the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in blood [6] and peritoneal fluid [37]. Metoprolol reduced the hepatic expression of proinflammatory cytokines and the plasma interleukin (IL)-6 level [9]. In contrast, the non-selective β-blocker propranolol enhanced inflammation and increased the TNF-α and IL-6 levels [38, 39]. The serum levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, are increased with stimulation by the selective β1-blocker atenolol [8] and by β2-blockers [40]. Hence, the benefits of β-blockers may also be immune mediated. Selective β-blockers have anti-inflammatory effects, which could explain the better sepsis outcomes in chronic β1-selective β-blocker users in this study.

Postmorbid usage of β-blockers after sepsis established was reported to improve circulatory and metabolic status and reduce mortality [10, 23]. In most clinical trials, β-blockers were started after 24 h of ICU admission [10, 21, 22]. On the other hand, premorbid β-blocker usage before sepsis development was reported to provide survival advantage in database study [11] or experimental study [9]. Ackland et al. found better protective effect of β-blocker, with reduction of proinflammatory cytokines, once it was given before septic insult than after induction of endotoxemia [9]. Our study provided clinical evidence for the benefit of premorbid β-blocker use in septic patients. We postulated that long-term, premorbid β-blocker use may increase patients’ tolerance to the excessive catecholamine surge during acute stress and contribute to hemodynamic or metabolic benefits long before sepsis occurred. Further prospective studies are needed to delineate the optimal timing of initiating β-blocker therapy.

Our findings are in line with previous findings that premorbid β-blocker exposure is associated with the improvement of outcomes in patients with sepsis [11,12,13]. Contrary to our findings, Singer et al. [12] reported that the mortality rate was lower among patients with premorbid exposure to non-selective β-blockers than among those with premorbid β1-selective β-blocker exposure. However, their study was based on Medicare administrative data, with patient inclusion in 2009–2011 according to ICD-9 diagnostic codes for sepsis, septic shock, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome, without consideration of clinical markers such as laboratory values and vital signs. In the present study, we used the Sepsis-3 criteria for patient inclusion, and considered a broad range of clinical information and data dating to 2015–2017, when sepsis management was more in line with treatment guidelines.

This study has several limitations. First, as it was retrospective, we could not determine the causal relationship between premorbid β1-selective β-blocker exposure and mortality. Second, it was based on the review of medical records from a single center. Disease severity was greater in our sample than in previous samples; thus, the observed benefits of β1-selective β-blockers in terms of sepsis outcomes may not extend to all septic patients. Third, the types of β-blocker prescribed were distributed unevenly; β1-selective β-blockers are preferred in our region when β-blocker use is indicated, and non-selective β-blocker use is predominant for certain diseases, such as liver cirrhosis, which may have caused bias. We attempted to correct for such bias by adjusting the multivariate regression and subgroup analyses for comorbidities. Fourth, as previous mentioned, β-blocker can influence the platelet and coagulation functions. However, we do not routinely evaluate platelet function or coagulation factors in the daily practice. Troponin-I, which is a useful marker to indicate myocardial injury, was also not routinely measured. We did not adjust it in the analysis since there was too much missing data of coagulation factors and troponin-I. Finally, we only collected the data from the point of ICU admission, which may had been treated partially in the emergency department or ordinary ward.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that premorbid β1-selective, but not non-selective, β-blocker use is associated with lower ICU mortality among septic patients. The protective effect of β1-selective β-blockers may be related to their role in the suppression of the overwhelming adrenergic response, enhancement of cardiac performance, improvement of vascular and microcirculation dysfunction, and anti-inflammatory effects. The results of this study increase our knowledge of the β-adrenergic activity during sepsis. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the therapeutic potential of β1-selective β-blocker use in septic patients.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- PF ratio :

-

PaO 2 /FiO 2 ratio

- APACHE II:

-

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II

- GCS :

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- WBC :

-

White blood cell

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

References

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). Jama. 2016;315(8):801–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287.

Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, Okuda J, Kurazumi T, Suhara T, Ueda T, et al. Sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction and β-adrenergic blockade therapy for sepsis. J Intensive Care. 2017;5(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-017-0215-2.

Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES. The sympathetic nerve--an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52(4):595–638.

Träger K, DeBacker D, Radermacher P. Metabolic alterations in sepsis and vasoactive drug-related metabolic effects. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2003;9(4):271–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00075198-200308000-00004.

Schouten M, Wiersinga WJ, Levi M, van der Poll T. Inflammation, endothelium, and coagulation in sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(3):536–45. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0607373.

Suzuki T, Morisaki H, Serita R, Yamamoto M, Kotake Y, Ishizaka A, et al. Infusion of the beta-adrenergic blocker esmolol attenuates myocardial dysfunction in septic rats. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10):2294–301. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000182796.11329.3B.

Norbury WB, Jeschke MG, Herndon DN. Metabolism modulators in sepsis: propranolol. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9 Suppl):S616–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000278599.30298.80.

Calzavacca P, Lankadeva YR, Bailey SR, Bailey M, Bellomo R, May CN. Effects of selective β1-adrenoceptor blockade on cardiovascular and renal function and circulating cytokines in ovine hyperdynamic sepsis. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):610. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-014-0610-1.

Ackland GL, Yao ST, Rudiger A, Dyson A, Stidwill R, Poputnikov D, et al. Cardioprotection, attenuated systemic inflammation, and survival benefit of beta1-adrenoceptor blockade in severe sepsis in rats. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):388–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c03dfa.

Morelli A, Ertmer C, Westphal M, Rehberg S, Kampmeier T, Ligges S, et al. Effect of heart rate control with esmolol on hemodynamic and clinical outcomes in patients with septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2013;310(16):1683–91. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.278477.

Macchia A, Romero M, Comignani PD, Mariani J, D'Ettorre A, Prini N, et al. Previous prescription of β-blockers is associated with reduced mortality among patients hospitalized in intensive care units for sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(10):2768–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b9509.

Singer KE, Collins CE, Flahive JM, Wyman AS, Ayturk MD, Santry HP. Outpatient beta-blockers and survival from sepsis: results from a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Surg. 2017;214(4):577–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.007.

Tan K, Harazim M, Tang B, McLean A, Nalos M. The association between premorbid beta blocker exposure and mortality in sepsis-a systematic review. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):298. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2562-y.

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–29. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009.

Bristow MR. beta-adrenergic receptor blockade in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101(5):558–69. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.5.558.

Sander O, Welters ID, Foëx P, Sear JW. Impact of prolonged elevated heart rate on incidence of major cardiac events in critically ill patients with a high risk of cardiac complications. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(1):81–8 discussion 241-242.

Vellinga NA, Boerma EC, Koopmans M, Donati A, Dubin A, Shapiro NI, et al. International study on microcirculatory shock occurrence in acutely ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(1):48–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000553.

Sanfilippo F, Corredor C, Fletcher N, Landesberg G, Benedetto U, Foex P, et al. Diastolic dysfunction and mortality in septic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(6):1004–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3748-7.

Bergström A, Andersson B, Edner M, Nylander E, Persson H, Dahlström U. Effect of carvedilol on diastolic function in patients with diastolic heart failure and preserved systolic function. Results of the Swedish Doppler-echocardiographic study (SWEDIC). Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6(4):453–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.02.003.

Magder SA. The ups and downs of heart rate. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):239–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232e50c.

Morelli A, Donati A, Ertmer C, Rehberg S, Kampmeier T, Orecchioni A, et al. Microvascular effects of heart rate control with esmolol in patients with septic shock: a pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9):2162–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a678d.

Balik M, Rulisek J, Leden P, Zakharchenko M, Otahal M, Bartakova H, et al. Concomitant use of beta-1 adrenoreceptor blocker and norepinephrine in patients with septic shock. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124(15-16):552–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00508-012-0209-y.

Morelli A, Singer M, Ranieri VM, D'Egidio A, Mascia L, Orecchioni A, et al. Heart rate reduction with esmolol is associated with improved arterial elastance in patients with septic shock: a prospective observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(10):1528–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-016-4351-2.

Mann DL, Kent RL, Parsons B, Cooper G. Adrenergic effects on the biology of the adult mammalian cardiocyte. Circulation. 1992;85(2):790–804. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.85.2.790.

Communal C, Singh K, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS. Opposing effects of beta(1)- and beta(2)-adrenergic receptors on cardiac myocyte apoptosis: role of a pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein. Circulation. 1999;100(22):2210–2. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.100.22.2210.

Communal C, Colucci WS, Singh K. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway protects adult rat ventricular myocytes against beta-adrenergic receptor-stimulated apoptosis. Evidence for Gi-dependent activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(25):19395–400. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M910471199.

Bristow MR, Feldman AM, Adams KF Jr, Goldstein S. Selective versus nonselective beta-blockade for heart failure therapy: are there lessons to be learned from the COMET trial? J Card Fail. 2003;9(6):444–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.10.009.

McCarter FD, James JH, Luchette FA, Wang L, Friend LA, King JK, et al. Adrenergic blockade reduces skeletal muscle glycolysis and Na(+), K(+)-ATPase activity during hemorrhage. J Surg Res. 2001;99(2):235–44. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsre.2001.6175.

Levy B, Gibot S, Franck P, Cravoisy A, Bollaert PE. Relation between muscle Na+K+ ATPase activity and raised lactate concentrations in septic shock: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;365(9462):871–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71045-X.

Kirkebøen KA, Strand OA. The role of nitric oxide in sepsis--an overview. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43(3):275–88. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-6576.1999.430307.x.

Schmidt C, Kurt B, Höcherl K, Bucher M. Inhibition of NF-kappaB activity prevents downregulation of alpha1-adrenergic receptors and circulatory failure during CLP-induced sepsis. Shock. 2009;32(3):239–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181994752.

Kimmoun A, Louis H, Al Kattani N, Delemazure J, Dessales N, Wei C, et al. β1-adrenergic inhibition improves cardiac and vascular function in experimental septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(9):e332–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001078.

Wei C, Louis H, Schmitt M, Albuisson E, Orlowski S, Levy B, et al. Effects of low doses of esmolol on cardiac and vascular function in experimental septic shock. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):407. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1580-2.

Hjemdahl P, Larsson PT, Wallén NH. Effects of stress and beta-blockade on platelet function. Circulation. 1991;84(6 Suppl):Vi44–61.

Adler B, Gimbrone MA Jr, Schafer AI, Handin RI. Prostacyclin and beta-adrenergic catecholamines inhibit arachidonate release and PGI2 synthesis by vascular endothelium. Blood. 1981;58(3):514–7.

Teger-Nilsson AC, Larsson PT, Hjemdahl P, Olsson G. Fibrinogen and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels in hypertension and coronary heart disease. Potential effects of beta-blockade. Circulation. 1991;84(6 Suppl):Vi72–7.

Mori K, Morisaki H, Yajima S, Suzuki T, Ishikawa A, Nakamura N, et al. Beta-1 blocker improves survival of septic rats through preservation of gut barrier function. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(11):1849–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2326-x.

Lang CH, Nystrom G, Frost RA. Beta-adrenergic blockade exacerbates sepsis-induced changes in tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 in skeletal muscle and is associated with impaired translation initiation. J Trauma. 2008;64(2):477–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.TA.0000249375.43015.01.

Schmitz D, Wilsenack K, Lendemanns S, Schedlowski M, Oberbeck R. beta-Adrenergic blockade during systemic inflammation: impact on cellular immune functions and survival in a murine model of sepsis. Resuscitation. 2007;72(2):286–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.07.001.

Muthu K, Deng J, Gamelli R, Shankar R, Jones SB. Adrenergic modulation of cytokine release in bone marrow progenitor-derived macrophage following polymicrobial sepsis. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;158(1-2):50–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.003.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported, in part, by research grants from the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 106-2314-B-350-001-MY3); the Novel Bioengineering and Technological Approaches to Solve Two Major Health Problems in Taiwan program, sponsored by the Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology Academic Excellence Program (MOST 108-2633-B-009-001); the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW106-TDU-B-211-113001); and Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V105C-207, V106C-045, V108C-195, V109B-010, V109D50-003-MY3-1). The funding institutions took no part in the study design, data collection or analysis, publication intent, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research idea and study design: MJ Kuo, RH Chou, and PH Huang; data acquisition: MJ Kuo, YW Lu, JY Guo, and YL Tsai; data analysis/interpretation: MJ Kuo and RH Chou; statistical analysis: MJ Kuo, RH Chou, and CH Wu; supervision or mentorship: PH Huang and SJ Lin. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee of the Taipei Veterans General Hospital approved this study and waived the requirement for informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ming-Jen Kuo and Ruey-Hsing Chou are co-first authors.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table.

Numbers of study subjects with missing data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuo, MJ., Chou, RH., Lu, YW. et al. Premorbid β1-selective (but not non-selective) β-blocker exposure reduces intensive care unit mortality among septic patients. j intensive care 9, 40 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-021-00553-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-021-00553-9