Abstract

Background

Patient education is identified as one of the core and fundamental management strategies in the management of allergic rhinitis. The Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines developed guidance for the management of allergic respiratory disease, and the guidelines are applicable to the international context. The ARIA guidelines for the pharmacy have specifically encouraged the creation of local pharmacist-led intervention in allergic rhinitis management. This study aims to develop a pharmacist-led educational model using a multi-phase study approach.

Method

In phase one, we conducted a literature review using four databases to extract relevant articles and clinical practice guidelines published between 2017 and 2022. The information was structured into a questionnaire consisting of patient education material (10 domains with 130 items) and pharmacist counseling scopes (15 domains with 43 items), with each item having a rating scale ranging from 1 (lowest) to 9 (highest) level of agreement. Fifty-two panellists, including otorhinolaryngologists and pharmacists, were invited to complete the questionnaire. A consensus agreement was considered when at least 70% of panellists scored 7 to 9 (critically important). A two-round survey was conducted, and descriptive analysis, inter-rater reliability (≥ 0.5–1 indicate moderate to excellent reliability), variation in the relative interquartile (VRIR < 0.3 indicate good stability), and variation in the coefficient of variation (VCV < 40% considered consensus achieved) were performed. In phase two, patient education material was developed into audio-visual format, and in phase three, patients rated its understandability and actionability using a validated Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool.

Results

In the round one Delphi survey, 43 panellists responded, with 171 out of 173 items achieving “consensus agreement” (75.4–100%). In the second survey, 32 out of 43 panellists responded, with most items (171 out of 173 items) stable across rounds and all items had acceptable internal consistency (VCV: − 12.21–15.81). Two items did not achieve “consensus agreement” (64%) but improved in round two (92.9%), however, instability was observed (VRIR: 0.36). These two items were retained in the model due to achieving the minimum level of agreement and internal consistency (VCV = 15.81). Inter-rater reliability was 0.608 and 0.970 in the respective rounds. Patients rated the educational material as understandable (81.8–100%) and actionable (100%).

Conclusion

The validated pharmacist-led education model, with its educational materials tested on end-users, provides structured patient education and pharmaceutical care in assisting patients with allergic rhinitis. The educational material allows the delivery of standardized information by the healthcare providers to the patients. Further research on the effectiveness of this model in improving patients’ symptom control and quality of life is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is an inflammatory reaction following allergens exposure, causing symptoms like rhinorrhoea, nasal congestion, and itchiness [1]. It results in significant financial burdens on healthcare, with annual costs in the U.S.A. reaching 3.4 billion USD while indirect cost accounted for 5.2 billion USD in 1996 [2]. The increasing prevalence of AR has led to a global prevalence of 1.0–54.5% up to 2020 [3]. The healthcare cost and economic burden are primarily due to the increasing prevalence of AR in industrialized countries [4].

AR is a chronic condition requiring patients’ self-management and healthcare providers’ support [5]. The fundamental of management involves educating patients on understanding disease nature, allergens avoidance, and medication adherence [1, 6,7,8]. However, there is a significant knowledge gap, with a range of 22–70.1% of patients having knowledge about AR [9, 10]. Non-adherence to intranasal corticosteroid is prevalent among AR patients (36.9–67.3%) [11,12,13]. Patients’ lack of knowledge and skill was predictor of non-adherence [6]. The current educational material online is not standardized, the techniques of intranasal spray administration have differed across online information [12, 18,19,20,21], leading to conflicting information for patients.

Pharmacist-led educational interventions improve patients' quality of life and symptom severity [14]. Pharmacists significantly influence patients' management of AR [15, 16] by setting goals for care and providing pharmacist-led educational interventions [17, 18]. The roles of pharmacists are included in the integrated pathway (ICPs) of Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines [19], which encourage the development of local standard pharmaceutical care guides for AR management [20]. ARIA is a non-governmental organization that educates, advocates and puts evidence-based management of AR and asthma into practice worldwide. The first ARIA documents were made by a panel of experts in 1999 that provide a basis for healthcare providers and health organizations to develop country-specific local standards of care [21].

This study aimed to develop and validate a pharmacist-led education model through a multi-phase approach, considering patient education and the need for local pharmaceutical care guidance.

Methods

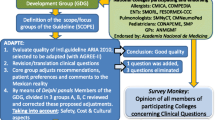

This study aimed to present a valid and reliable pharmacist-led education model for educating AR patients. This material was developed using a methodological approach in three phases: (1) the modified Delphi process; (2) the design and development of the educational video; (3) the evaluation of the educational video (Fig. 1).

Phase 1: modified Delphi process

The Delphi technique is a systematic method for controlling group communication to address an issue as a whole [22]. It has increasingly been used in pharmacy practice research to achieve consensus on knowledge, roles, competencies, medication literacy service optimization, and a collaborative model [23].

We adopted the modified Delphi method that used structured items with a 9-point Likert scale in round one Delphi survey. This quantitative technique was used due to readily available research model development information [23, 24]. This technique helped to simplify consensus-building in respective domains [25]. The two-round modified Delphi process utilized controlled feedback on expert input to obtain consensus among a panel of experts through three stages: preparing, conducting, and analysing [26] (Fig. 1).

Preparing

The Delphi process was started on a literature review of academic journals, randomised controlled trials, international and local clinical practice guidelines, and reviewed articles. A search for practice guidelines and journals in the management of AR was performed on different databases, including PubMed, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and EBSCOHost. The keywords entered included “allergy rhinitis and practise guidelines”, “clinical practice guidelines”, “patient education”, “pharmacist-led educational protocol”, “pharmacist-led intervention”, and “AR”.

The relevant literature published between 2017 and 2022 in the English language by excluding articles with the title of “paediatric”, “child”, “children”, “infant”, and “adolescent” were searched. Practice guidelines from various countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Malaysia, were compared to the Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guideline. The initial search generated over 604 articles gathered in the Zotero citation manager to identify duplication. The principal investigator, who has research experience in otorhinolaryngology, read these articles and removed irrelevant ones. Finally, 37 articles were reviewed for potential competencies. A list of 173 competencies items was generated, with the definition, pathology, and causes of AR were adapted from the first ARIA guidelines developed in year 2008 [21].

A superior reference panel, including consultants, an otorhinolaryngology specialist, and researchers, aimed to construct, define, and set domains for the study model. A consensus meeting was held to confirm competency items [27]. Senior pharmacists discussed competencies items related to pharmacy practice. The Delphi questionnaire, including patient education information and pharmacist counselling scope, was finalized by an academic supervisor. A nine-point Likert scale from very low (1) to very high (9) agreement levels was used. An open response field for additional comments was added to gain extra insight. The domains and the associated items are presented in Table 1.

Conducting

-

I.

Expert panel

The criteria for expert panel selection include (i) otorhinolaryngologist; (ii) family medicine specialist; (iii) medical doctor with at least 5 years of experience in the Otolaryngology department; (iv) pharmacist with five years of experience in the hospital pharmacy practices [28]. The literature suggests that the minimum number of panellists ranges from 10 to 18 per area of expertise [29]. The study team sampled a minimum of 10 panellists from each area of expertise. Based on a similar study, a ratio of medical doctors to pharmacists 3:1 was used to sample the panellists [30], resulting in a sample size of 30 medical doctors and 10 pharmacists. By estimating 20% of the non-response rate, the research team invited 37 medical doctors and 15 pharmacists. A minimum response rate of 70% is required for a Delphi survey round (65).

-

II.

Delphi survey rounds

Round one In round one (R1), the panellists were invited via telephone calls, email, and face-to-face meeting. The questionnaires were sent to them by email (n = 32) and hand-delivered (n = 20). Each panellist was given a 2-week period to complete the first round of the survey. Those who were yet submitted their comments after the due date were given a 1-week extension and an email to remind them [31]. After the first round, the data were analysed to determine the individual and group median scores.

Round two In round two (R2) of the Delphi survey, the questionnaire was sent to them by email (n = 20) and hand-delivered (n = 23). Each panellist was sent a first-round report illustrating each item’s individual and group median scores. Participants were invited to re-rate the consensus-building process only for items needing clarification, not achieving a “consensus agreement”, or new items suggested by the panellist in R1 via free-text responses. Up to two email reminders were sent to request completion [31].

Analysis The data analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 and Microsoft Excel®. The consensus of the agreement (%) for each item was calculated as the number of respondents rated at a particular score divided by the total of panel responses to that item. The central tendency and dispersion measures were calculated [24, 32, 33].

In the first scenario, a “consensus agreement” was defined as 70% of the panellists scoring 7–9 [34]. The score within this range indicated a “critically important” item and would be accepted and acknowledged in the subsequent round without having to re-rate [32, 33, 35]. Besides, the consensus for an item is considered achieved by using an alternative criterion of the interquartile range (IQR) ≤ 2.00 on a 9-point scale [36].

In the second scenario, a “consensus disagreement” is defined as 70% of the panellist scoring 1–3, where these scores are defined as “not important item”, and would not be presented to the next round. They would be dropped from the model [32, 33, 35]. No specific cut-off of IQR value indicates absolute disagreement. An IQR of 3.00 signify the least agreement was adapted as a reference point [37].

In the third scenario, the items which scored 4 to 6 are considered “important but not critical” to include in the model and would be brought forward to the next round for re-rating [32, 33, 35].

In the fourth scenario, the items that received comments from the panellist were collated for discussion among the study team members. Literature reviews were performed to confirm the panellists’ suggestions [24, 32]. The items with changes made were presented in the round two surveys for re-rating.

Triangulation strategies were used to determine consensus in Delphi survey rounds, using parameters like IQR, variation in the relative interquartile (VRIR), and variation in the coefficient of variation (VCV). Mann–Whitney’s U test analysis was used to check statistically significant differences between rounds, with a p-value less than 0.05 [33].

The study assesses proximity responses among panellists to achieve consensus, using an IQR of less than 0.5. Group stability is achieved when the relative interquartile range (VRIR) variation is less than 0.30. Internal agreement is indicated by a coefficient of variation (VCV) of less than 40% between rounds [33]. Inter-rater reliability is determined using intra-class correlation (ICC) estimates. The ICC 95% confidence intervals were calculated using a mean rating (k = 43), absolute agreement, and a 2-way mixed-effects model [38].

Phase 2: design and development of the educational video

The research team created an 8-min educational video using the CanvaⒸ software programme. Each statement was supported by a colourful illustration and audio description that was easily understood. The topics covered in the video include AR definition, causes, risk factors, disease nature, symptoms, and methods to effectively manage the symptoms. The methods involved allergen identification and avoidance strategies, the importance of regular use of intranasal corticosteroids, and attending follow-up at the clinic. The measures to be taken when symptoms become worse, and the consequences of inadequate control of AR were included in the last part of the video.

Phase 3: evaluation of the educational video

A Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT-A/V) [39] was used to evaluate audio-visual patient education materials. The PEMAT-A/V tool (English) was validated by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [40]. This tool had a moderate agreement per Kappa (average K = 0.57), strong agreement per Gwet’s AC1 (average = 0.74), and strong internal consistency (α = 0.71; average item-total correlation = 0.62). The tool evaluates end-user’s “understandability” and “actionability” in patient education materials. “Understandability” domain assesses content, word choice, style, organization, layout, design, and visual aids. The “Actionability” domain evaluates their ability to take action. The domain of “Understandability” consists of 11 questions after excluding two questions that did not apply to video format, while “Actionability” has 4 questions [40].

A Malay-translated PEMAT-A/V (M) version with excellent inter-rater reliability 0.791 (95% CI: 0.635–0.915) and 0.733 (95% CI: 0.559–0.887) in understandability and actionability domains, respectively, was used in this study. PEMAT-A/V (M) was adapted for the local population and obtained permission from the originator [39].

The PEMAT-A/V uses a scoring system (scale of 0 to 100%) to generate the score in percentage by summing the score of each item, whereby 1 point is given to the item marked “agree” and 0 points to disagree. The total score was divided by the total number of items and multiplied by 100% to generate each score for “understandability” and “actionability”. A cut-off of 70% is used to determine whether the patient education material in the form of video is sufficiently “understandable” and “actionable” by the end-users [40]. Seventy-nine patients with AR were estimated using a G* power sample size, with an effect size of 0.2 based on Cohen's d [41], a constant proportion of 0.5, a significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.95. A consecutive sampling technique was employed to recruit patients who diagnosed with AR attending the outpatient otorhinolaryngology clinic.

Results

Expert panel

In R1, of the 52 panellists invited, 25 otorhinolaryngologists, 13 pharmacists, 4 senior medical doctors, and a family medicine specialist responded (response rate: 82.7%). They had working experience of 6–27 years, and the estimated proportion of AR patients managed in a month ranged from 25 to 75% (Table 2). The R2 received a response rate of 74.4%, with 32 out of 43 panellists responding.

Inter-rater reliability

In the R1, the reliability among panellists was moderate with an ICC estimate of 0.608 (95% CI 0.512–0.695), but improved to excellent reliability with an ICC estimate of 0.970 (95% CI 0.945–0.987) in the R2 survey.

Two-round Delphi survey

Patient educational material

In R1, a “consensus agreement” was achieved for 9 domains consisting of 111 items, with 85.8 to 95.9% rated critically important. However, two out of 19 items under the domain “allergen identification and avoidance” did not meet “consensus agreement”, with 64.0% of the panellists rating them as critically important. These items had a median score of 7.50 (IQR: 5.00–9.00), indicating the least agreement among the panellists. The statements of these two items were “wearing goggles” and “keeping doors and windows closed”. Their comments were that “what types of goggles” and "the instruction of execution were not explicit", respectively. Panellists suggested that “types and timing of wearing goggles” and "the timing for patients to take action” be specified (Additional file 1: Appendix I: Rating of panellist in R1 survey). The panellist's suggestions were adopted and brought the items forward for re-rating in subsequent rounds. In R2, the median score improved to 8.50, with 92.9% rating the items as critically important (Table 3). Although there was slight group instability between rounds (VRIR = 0.36) (Fig. 2a), the VCV was 15.81% (< 40.0%), indicating a consensus was achieved.

In R2, 90.9–97.0% of panellists rated all items as critically important. The relative interquartile range between rounds showed group stability (VRIR = − 0.11–0.36), with variation within acceptable ranges (− 3.86 to 15.81%). Mann–Whitney’s U test did not show significant differences in ratings between rounds at all domains (p = 0.317–1.000, z = − 1.000 to 0.000) (Table 3).

Pharmacist counselling scopes and algorithm

The R1 found that 15 domains with 43 items achieved consensus agreement, with 86.5–100% rating them as critically important. In R2, 87.5–100% of panellists rating the items as critically important (Additional file 1: Appendix I). Between-round variations were stable across 0.00 to 0.13 (VRIR) and − 12.21 to 6.84% (VCV) (Fig. 2b and d).

The first and ninth domains showed slightly higher VRIR, 0.09 and 0.13, respectively (Fig. 2b). The first domain focused on patient selection criteria with the inclusion of moderate-to-severe AR for counselling and management, while the ninth domain involved a flow chart for stepwise patient assessment and counselling. The panellists suggested that patients with all levels of severity should be included, and the flowchart structure was improved for better clarity. Improvements were observed in the mean score, IQR, and percentage of consensus agreement in R2 (Table 3).

The highest variation between rounds was observed in the "Evaluation of existing nasal spray users" (VCV = − 12.21). The R1 statement was to evaluate patients' corticosteroid nasal spray administration technique and correct it when necessary. However, some panellists deemed it unnecessary due to the heavy patient load. A statement “considering patients with uncontrolled symptoms or poor clinical outcomes only if human resources are a limitation” was added in R2. The consensus agreement dropped slightly from 97.7% in R1 to 90.6% in R2. The study team adopted the statement in R2 by considering the panellists’ comments and patient census (Table 3).

No significant differences were found between rounds, as shown in the Mann–Whitney U test (p = 0.317–1.000) (Table 3). The full pharmacist-led educational material is available in Additional file 1: Appendix II: Pharmacist-led education material.

Educational video evaluation

The third study phase recruited 79 participants diagnosed with AR, where the median age of the respondents was 47.00 (IQR: 33). The majority were female (60.8%), had secondary school education (50.6%), and had Malay ethnicity (54.4%).

Overall, the education material was “understandable” and “actionable”; the material secured at least 70% for each domain. Of 11 items under the “understandability” domain, 6 scored 100%, 3 scored 98.7%, and 1 scored 97.5% and 89.9%, respectively. Although all items achieved the minimum score of 70%, the least agreement rated was on ‘the material allows the user to hear the words clearly (e.g., not too fast, not garbled)’. Meanwhile, the “actionability” domain secured scores of 100% for all items (Table 4).

Discussion

This study developed a pharmacist-led education model using a multi-phase approach. One of the approaches used, the Delphi technique, was convenient, time- and cost-efficient for panellists from diverse backgrounds [42]. The Delphi technique emerged and retained important competencies after reflection while restructuring less clearly defined ones [43, 44]. This study assessed group stability, internal agreement, and inter-rater reliability, contrasting previous studies that reported consensus agreement in percentage [31] or median score [45].

The study adopted a two-round modified Delphi process, with structured items and a 9-point Likert scale in the first round. This approach simplifies consensus-building and is suitable for generating consensus on critically important topics for patients [25]. The quantitative approach was adapted based on the availability of basic information from the pharmacist-led educational model [23, 24]. This method can be applied when the information needed to be delivered to patients is broad that panellists are needed to reach a consensus [46].

All items met the standard for consensus agreements among panellists in the final round. Nonetheless, two items under “allergen avoidance” did not achieve consensus due to impractical action and unclear instructions in R1. The item indicating “Wearing goggles” was incomplete and unclear, so it was clarified as “Wear wrap-around sunglasses when being outside.” The item “Ensuring the door and window are kept closed” was unrealistic in real life. The panellists suggested closing windows and doors when outdoor air quality was poor and providing examples of poor air quality. Consensus agreements were achieved for these items in R2, but slight instability was noticed for these two items. The application of VCV suggested an internal agreement was reached for these items in R2. Additionally, an improvement in the proportion of panellists rating items with scores of “7 to 9” was observed, indicating that the items were critically important to be included in the model.

The second part of the model focuses on pharmacist counselling scopes and algorithms. In R1, a satisfactory consensus agreement was achieved, and all domains remained stable. However, some suggestions for statement improvement were adapted for R2, resulting in higher consensus agreement. For example, the panellist suggested recruiting all patients into the pharmacist-led education model instead of only adult patients with moderate-to-severe AR. This was based on the substantial patient load at outpatient pharmacies, which refilled 44.9 million prescriptions in 2021 in the public healthcare setting [47]. Improvements were observed in R2, with an increase in “consensus agreement” from 88.1% to 90.6% and a reduction in the width of the IQR from 7.25–9.00 to 8.00–9.00.

The stepwise pharmacological management approach and disease classification adopted from the ARIA guidelines raised concerns among panellists, who assumed a shift from physicians to pharmacists in patient treatment decisions. The statement in R1 was restructured in accordance to the level of agreement of the panellist to include this information in the pharmacist counselling. The panellists might misunderstand that the pharmacists would change the regimes by following the stepwise pharmacological treatment according to the disease severity. The R2 rating explained that the inclusion was only for the knowledge of practising pharmacists, with the concern that most pharmacists had inadequate awareness of ARIA guidelines (40.4%) [48]. The revised version assuring the panellist that there is no shift of the role of physicians to pharmacists in the treatment decision.

This study tested the understanding of patient education material in video format on patients at the final phase, enhancing its robustness. Educational videos were the most effective medium for improving knowledge in an easy-to-understand way [49]. The study converted the patient education material from text to audio-visual format to facilitate patient understanding [49,50,51]. A local study found that providing patient education via video had the highest impact on nasal spray usage [52]. However, the video mainly focused on nasal spray administration without addressing other aspects of AR management.

Patients with adequate information about their diseases and management strategies are more proactive in medication intake and controlling symptoms [7]. However, 31% of YouTube’s videos on AR were found unreliable and may negatively impact patient outcomes [53]. Access to legitimate sources is also a concern due to differences in educational background and patient health literacy levels. Patient education information varies slightly among online references [7, 54,55,56,57,58,59]. Hence, having the material validated by an expert panel to ensure its validity and usability is crucial. Testing the material on patients further confirms its credibility.

This study developed a pharmacist-led education model to provide comprehensive information on AR and counselling. In contrast, the previous studies focused on educating the pharmacist and their assistant through intensive training and workshops [16, 28, 60]. Our study model includes patient education, healthcare professional support, and patient selection criteria for pharmacists to support AR patient management in public health services settings. The model also includes specific parameters like symptom control, quality of life, and nasal spray administration technique assessment. This approach may give greater patients self-assurance in their ability to cope with AR and achieve desired symptom control levels [18].

The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT-A/V) was utilized to assess patients’ understandability and actionability after watching the video. Unlike other tools, PEMAT-A/V evaluates content dimensions, word choice, style, organization, layout, design, and visual aids [39]. Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) was also used to test patient education materials, but focusing more on instruction and actionability [61]. The Educational Content Validation Instrument in Health that tests educational content in video was considered for adaptation, but its usability could be limited due to its focus on written content without considering images, graphics, or drawings [62].

Limitations

The choice to involve local panellists may restrict the applicability of this model on a global scale. Paradoxically, this limitation can be viewed as a strength of the study, as local panellists possess an in-depth understanding of the specific nuances and practices within the local context, thereby enhancing the model's relevance and effectiveness within that specific region [31]. The use of consecutive sampling in phase 3 lacked the nature of probability sampling. However, the inclusion of all accessible participants would be considered most reflecting the common scenario in a clinical setting, and it is a better choice of non-probability sampling as compared to convenience sampling.

Conclusion

The pharmacist-led education model in managing patients with AR achieved consensus agreement among the expert panels, with good stability and within-range VCV between rounds. Two items indicated lesser stability remained in the model, with most of the panels deemed that these items were critically important and further supported by acceptable VCV. Therefore, this model is a valid tool for healthcare providers, especially among pharmacists conducting educational interventions in patients with AR. Most importantly, a high level of understandability and actionability of the educational material among the targeted population, i.e. patients with AR, would promote the adaption of this model into daily clinical practice and potentially serve as a standard guide for healthcare providers in patient education.

Availability of data and materials

The data belonged to Clinical Research Centre and the Perak State Health Department under the Malaysian Ministry of Health. Hence, it cannot be shared publicly. However, with a reasonable request, should any party require the data, they can send their request to the corresponding author with permission from the Director General of Health prior to being shared with any party.

References

Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, Denburg J, Fokkens WJ, Togias A, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008*: ARIA: 2008 update. Allergy. 2008;63:8–160.

Dierick BJH, van der Molen T, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, Muraro A, Postma MJ, Kocks JWH, et al. Burden and socioeconomics of asthma, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and food allergy. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;20:437–53.

Savouré M, Bousquet J, Jaakkola JJK, Jaakkola MS, Jacquemin B, Nadif R. Worldwide prevalence of rhinitis in adults: a review of definitions and temporal evolution. Clin Transl Allergy. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/clt2.12130.

Pawankar R, Canonica GW, Holgate ST, Lockey RF, Blaiss MS. World Allergy Organization (WAO) White Book on Allergy: Update 2013 [Internet]. United States of America: World Allergy Organization; 2013 p. 248. Available from: https://www.worldallergy.org/UserFiles/file/WhiteBook2-2013-v8.pdf.

Cvetkovski B, Kritikos V, Tan R, Yan K, Azzi E, Srour P, et al. A qualitative investigation of the allergic rhinitis network from the perspective of the patient. npj Prim Care Respir Med. 2019;29:35.

Bender BG. Motivating patient adherence to allergic rhinitis treatments. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15:10.

Levin ME. Education for allergic rhinitis. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;27:101–6.

Bousquet J, Anto JM, Bachert C, Baiardini I, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Walter Canonica G, et al. Allergic Rhinitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:95.

Hellings PW, Dobbels F, Denhaerynck K, Piessens M, Ceuppens JL, De Geest S. Explorative study on patient’s perceived knowledge level, expectations, preferences and fear of side effects for treatment for allergic rhinitis. Clin Transl Allergy. 2012;2:1–8.

Retinasekharan S, Md Shukri N, Ismail AF, Abdullah B. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of intranasal corticosteroid in allergic rhinitis patients: development of a new questionnaire. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;10:8.

Manjit Singh PK, Krishnan EK, Mat Lazim N, Yaacob NM, Abdullah B. Medication adherence to intranasal corticosteroids in allergic rhinitis patients with comorbid medical conditions. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:2459.

Lee BW, Lee CS, Lim ER, Tham AC. Intranasal steroid use and satisfaction in allergic rhinitis: a cross-sectional study from an Asian perspective. ORL. 2022;84:55–61.

Hankin CS, Cox L, Lang D, Bronstone A, Wang Z, Lepore MS, et al. Medical costs and adherence in patients receiving aqueous versus pressurized aerosol formulations of intranasal corticosteroids. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33:258–64.

José J, Cvetkovski B, Kritikos V, Tan R, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Lourenço O. Interventions delivered in the community pharmacy to manage allergic rhinitis- a systematic review of the literature. Pharmacy. 2020;8:80.

Cvetkovski B, Tan R, Kritikos V, Yan K, Azzi E, Srour P, et al. A patient-centric analysis to identify key influences in allergic rhinitis management. npj Prim Care Resp Med. 2018;28:34.

Smith S, Porteous T, Bond C, Francis J, Lee AJ, Lowrie R, et al. The Help for Hay Fever community pharmacy-based pilot randomised controlled trial for intermittent allergic rhinitis. npj Prim Care Respir Med. 2020;30:23.

Abdullah B, Kandiah R, Hassan NFHN, Ismail AF, Mohammad ZW, Wang DY. Assessment of perception, attitude, and practice of primary care practitioners towards allergic rhinitis practice guidelines: development and validation of a new questionnaire. World Allergy Organ J. 2020;13: 100482.

Chew C-C, Chang C-T, Lim X-J, Yong W-Y, George D, Letchumanan P, et al. The management of allergic rhinitis by pharmacists in public services: a proposed PhaRmacISt-led Education Model (AR-PRISE). J of Pharm Policy and Pract. 2022;15:80.

the ARIA Study Group, the MASK Study Group, Bousquet JJ, Schünemann HJ, Togias A, Erhola M, et al. Next-generation ARIA care pathways for rhinitis and asthma: a model for multimorbid chronic diseases. Clin Transl Allergy. 2019;9:44.

Bosnic-Anticevich S, Costa E, Menditto E, Lourenço O, Novellino E, Bialek S, et al. ARIA pharmacy 2018 “allergic rhinitis care pathways for community pharmacy.” Allergy. 2019;74:1219–36.

European Forum for Research and Education in Allergy and Airway Diseases. Euforea | ARIA [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 22]. Available from: https://www.euforea.eu/aria.

Turoff M, Linstone HA. The Delphi method: techniques and applications [Internet]. 2002. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237035943_The_Delphi_Method_Techniques_and_Applications.

Jaam M, Awaisu A, El-Awaisi A, Stewart D, El Hajj MS. Use of the Delphi technique in pharmacy practice research. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2022;18:2237–48.

Hsu C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12:1–8.

Shariff NJ. Utilizing the Delphi Survey Approach: A Review. J Nurs Care [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2022 May 23];04. Available from: https://www.omicsgroup.org/journals/utilizing-the-delphi-survey-approach-a-review--2167-1168-1000246.php?aid=51677.

Spinelli T. The Delphi decision-making process. J Psychol. 1983;113:73–80.

Naghi M, Salem M. A modified Delphi study for the development of a leadership curriculum for pediatric oncology. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2021;22:1659–65.

Arsoy G, Varış A, Saloumi LM, Abdi A, Başgut B. Insights on allergic rhinitis management from a Northern Cyprus perspective and evaluation of the impact of pharmacist-led educational intervention on patients’ outcomes. Medicina (Lithuania). 2018;54:83.

Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag. 2004;42:15–29.

Gopal, Cynthia Priyadarshin. An evaluation on the effectiveness, development and establishment of the pharmacist-assisted heart failure management tools. [Penang]: Universiti Sains Malaysia.; 2016.

Gopal CP, Ranga A, Joseph KL, Tangiisuran B. Development and validation of algorithms for heart failure patient care: a Delphi study. Singapore Med J. 2015;56:217–23.

Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31:684–706.

Mengual-Andrés S, Roig-Vila R, Mira JB. Delphi study for the design and validation of a questionnaire about digital competences in higher education. Int J Educ Technol High Educ. 2016;13:12.

Downar J, Hawryluck L. What should we say when discussing “code status” and life support with a patient? A Delphi analysis. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:185–95.

Dorcas B, Lara M, Shawna G, Bev S, Peter T, Clifton O. BI. The OMERACT Handbook [Internet]. Canada: OMERACT; 2021. Report No.: 2.1. Available from: https://omeract.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/OMERACT-Handbook-Chapter-Final-June_2_2021.pdf.

von der Gracht HA, Darkow I-L. Scenarios for the logistics services industry: a Delphi-based analysis for 2025. Int J Prod Econ. 2010;127:46–59.

Hahn EJ, Rayens MK. Consensus for tobacco policy among former state legislators using the policy Delphi method. Tob Control. 1999;8:137–40.

Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–63.

Wong ST, Saddki N, Arifin WN. Reliability of the Bahasa Malaysia version of Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool. Malaysian J Public Health Med. 2018;18:63–4.

Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96:395–403.

Cohen J. A power primer. Phychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–9.

Waggoner J, Carline JD, Durning SJ. Is there a consensus on consensus methodology? Descriptions and recommendations for future consensus research. Acad Med. 2016;91:663.

Rana J, Sullivan A, Brett M, Weinstein AR, Atkins KM, SaT Delphi Working Group. Defining curricular priorities for student-as-teacher programs: a National Delphi Study. Med Teach. 2018;40:259–66.

Penciner R, Langhan T, Lee R, McEwen J, Woods RA, Bandiera G. Using a Delphi process to establish consensus on emergency medicine clerkship competencies. Med Teach. 2011;33:e333-339.

Feagan BG, Lémann M, Befrits R, Connell W, D’Haens G, Ghosh S, et al. Recommendations for the treatment of Crohn’s disease with tumor necrosis factor antagonists: an expert consensus report. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:152–60.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–15.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Pharmaceutical Services Programme Annual Report 2021 [Internet]. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Pharmaceutical Services Programme Annual; 2021 p. 190. Available from: https://www.pharmacy.gov.my/v2/sites/default/files/document-upload/laporan-tahunan-program-perkhidmatan-farmasi-2021_0.pdf.

Abdullah B, Ramli RR, Shukri NM, Mohamad S. Closing the knowledge gap in Malaysian pharmacists: a virtual Allergic Rhinitis Boot Camp initiative. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2021;16:775.

Latif S, Ahmed I, Amin MS, Syed I, Ahmed N. Exploring the potential impact of health promotion videos as a low cost intervention to reduce health inequalities: a pilot before and after study on Bangladeshis in inner-city London. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2016;8:66–71.

Isaacs T, Hunt D, Ward D, Rooshenas L, Edwards L. The inclusion of ethnic minority patients and the role of language in telehealth trials for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18: e256.

Morony S, McCaffery KJ, Kirkendall S, Jansen J, Webster AC. Health literacy demand of printed lifestyle patient information materials aimed at people with chronic kidney disease: are materials easy to understand and act on and do they use meaningful visual aids? J Health Commun. 2017;22:163–70.

Nasir FB, Mann BS. Patient education on nasal spray technique for allergic rhinitis. Int J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;7:250.

Doluoglu S, Gultuna S. Are YouTube videos on allergic rhinitis a good source of information for patients seeking a cure for their illness? Revue Française d’Allergologie. 2021;61:568–72.

DeShazo RD, Kemp SF. Patient Education: Allergic Rhinitis (Beyond the Basics). Topic 370. UpToDate. Wolter Kluwer; 2021. p. 1–12.

Sur DKC, Plesa ML. Treatment of allergic rhinitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92:985–92.

Kelleher KC. Optimal technique for application of corticosteroid nasal spray. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94:185.

Jean T. Allergic Rhinitis [Internet]. Medscape. 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 14]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/134825-overview.

Fowler J, Sowerby LJ. Using intranasal corticosteroids. CMAJ. 2021;193:E47.

Ambizas EM, Dimitropoulos E. Allergic rhinitis and intranasal corticosteroid sprays. US Pharm. 2015;40:8–11.

Porteous T, Wyke S, Smith S, Bond C, Francis J, Lee AJ, et al. ‘Help for Hay Fever’, a goal-focused intervention for people with intermittent allergic rhinitis, delivered in Scottish community pharmacies: study protocol for a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:217.

Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills [Internet]. American Journal of Nursing; 1996 [cited 2023 Apr 19]. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Citation/1996/12000/Teaching_Patients_with_Low_Literacy_Skills.22.aspx.

de Leite S, Áfio ACE, de Carvalho LV, da Silva JM, de Almeida PC, Pagliuca LMF. Construction and validation of an Educational Content Validation Instrument in Health. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71:1635–41.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article.

Funding

This study is not funded by any organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first two authors each wrote the first draught of the manuscript. The third and fourth edited and reviewed the article. The fifth author provided administrative support and proof-read the article. The last authors proof-read and finalized the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval to conduct this study has been obtained from the Malaysian Medical Research & Ethics Committee. This study has been registered with the Malaysian National Medical Research Register [NMRR ID-22-01229-XXW (IIR)].

Consent for publication

All authors agree to the submission of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Appendix I. Rating of panellist in R1 survey. Appendix ll. Pharmacist-led education material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chew, CC., Lim, XJ., Letchumanan, P. et al. Development and validation of a pharmacist-led education model in allergic rhinitis management: a multi-phase study. J of Pharm Policy and Pract 16, 116 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-023-00625-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-023-00625-1