Abstract

Background

Phosphorus (P) is the limiting nutrient in many mature tropical forests. The ecological significance of declining P stocks as soils age is exacerbated by much of the remaining P being progressively sequestered. However, the details of how and where P is sequestered during the ageing in tropical forest soils remains unclear.

Results

We examined the relationships between various forms of the Fe and Al sesquioxides and the Hedley fractions of P in soils of an incipient ferralitic chronosequence on an altitudinal series of gently sloping benches on Green Island, off the southeastern coast of Taiwan. These soils contain limited amounts of easily exchangeable P. Of the sesquioxide variables, only Fe and Al crystallinities increased significantly with bench altitude/soil age, indicating that the ferralisation trend is weak. The bulk of the soil P was in the NaOH and residual extractable fractions, and of low lability. The P fractions that correlated best with the sesquioxides were the organic components of the NaHCO3 and NaOH extracts.

Conclusions

The amorphous sesquioxides, Feo and Alo, were the forms that correlated best with the P fractions. A substantial proportion of the labile P appears to be organic and to be associated with Alo in organic-aluminium complexes. The progression of P sequestration appears to be slightly slower than the chemical and mineralogical indicators of ferralisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Phosphorus (P) is the single most limiting nutrient in many mature tropical forests (Vitousek 2004). Even where N and cationic nutrients are important, they are often co-determinants with P (Baillie et al. 1987; Wright et al. 2011). P is relatively stable in most soils, and can even accumulate in the organic layers of some forest soils, such as in humid subtropical subalpine Taiwan (Shiau et al. 2018; Wu and Chen 2005). However, prolonged and intense weathering, leaching and erosion generally deplete P stocks, although slowly in most cases (Vitousek 2004). The ecological significance of declining P stocks as soils age is exacerbated by much of the remaining P being progressively sequestered in stable complexes and becoming less labile. Shortage of P can significantly hinder the cycling of other nutrients, as in montane soils in Borneo, where it inhibits the decomposition of organic matter and induces N deficiency (Kitayama et al. 2004).

Many studies have shown that iron and aluminium are involved in the immobilisation of P in intensively weathered tropical soils, either through co-precipitation as Fe and Al phosphates or by sorption onto the variably charged surfaces of particles of various free oxides and hydroxides (the ‘sesquioxides’) (Metzger 1941; Ghani and Islam 1946; Dubus and Becquer 2001). The sesquioxides are residual weathering products, and accumulate as aluminosilicate minerals are progressively weathered (Blume and Schwertmann 1969; Nagatsuka 1972). The increasing quantities and crystallinities of sesquioxides mean that soil capacity to sequester P often increases with age (Walker and Syers 1976). As well as the sesquioxides, stable fractions of the soil organic matter can also immobilise P by sorption and incorporation (Yusrani 2010).

In their summary of the general decrease in P lability with soil age, Walker and Syers (1976) depicted most inorganic P being finally occluded and non-labile within accreting crystalline sesquioxide particles. The organically sequestered P is shown as increasing to a broad mid-age maximum, but then declining with advancing pedo-senility. This paradigm has clarified general trends in P dynamics during the ageing of soils in tropical forests and elsewhere, and has been a useful start point for much subsequent detailed research (Vitousek 2004; Richter et al. 2006; Daniela et al. 2010; Turner and Condron 2013).

Other studies have focused on the contributions of the different sesquioxides as sites for P sorption and immobilisation, particularly the relative effects of the amorphous (oxalate extractable, Feo and Alo) and free forms (citrate-dithionite-bicarbonate extractable, Fed and Ald) (Cajuste et al. 1994; Syers et al. 1971). Some have examined how the quantities and rates of sorption from solutions of known initial P contents are related to various sesquioxides. The findings are variable, as the effects can depend on the lithology of soil parent materials. Adejumo and Omueti (2016) found that P sorption was best correlated with Feo in soils from sedimentary rocks in Nigeria, whereas the both amorphous and crystalline forms were involved in soils derived from Basement Complex granites and gneisses. However, it often appears that amorphous Feo and Alo are more active than the crystalline forms (Singh and Gilkes 1991; Udo and Uzu 1972) found both amorphous (Feo and Alo) and crystalline (Fed–Feo and Ald-Alo) forms were active sorbents in Nigeria, but Alo was the most active. In contrast, Karim and Adams (1984) found that sorption was better correlated with Fed and Ald in a toposequence of soils in Malawi. They also noted that kaolinite accounted for up to one quarter of the total P sorption, especially in midslope soils. Saunders (1965) concluded that P sorption in topsoils was most closely related to organic matter in topsoils, but that various Fe and Al sesquioxides were more significant in subsoils, and that sorption initially increased with weathering intensity, but declined in highly weathered soils. Bortoluzzi et al. (2015) found that goethite and ferrihydrite were more active in P sorption than more crystalline and less hydrated hematite and gibbsite in an altitudinal sequence of basaltic Ferralsols in Southern Brazil.

An alternative approach is to examine the loci and lability of the P once it is sorbed, using Hedley-type P fractionation. As with the sorption studies, fractionation results can vary with the lithology of the soil parent materials (Daniela et al. 2010). Maranaguit et al. (2017) found that most of the P in highly weathered soils under different land uses in Indonesia was inorganic, and that some P in the putatively less labile Hedley P fractions was available for uptake by rubber and oil palm crops. Agbenin (1994) fractionated P in two toposequences in Brazil: one on homogenously high-P parent material and one on heterogenous parent materials. He concluded that P was immobilized in the mid- and lower slope soils of both toposequences by weathering and occlusion in the accreting amorphous sesquioxides. Guo et al. (2000) found that NaHCO3-P and some residual P were the main sources depleted by exhaustive cropping on less weathered soils, but NaOH-P was accessed more in highly weathered soils. Baumann et al. (2020) found that about a quarter of the total P in the topsoils of three imperfectly drained soils in Northern Germany was labile (i.e. water + resin + bicarbonate extractable) and much of the rest was sorbed on sesquioxides, including a substantial proportion of occluded P, especially in the subsoils. Dubus and Becquer (2001) found that P was intensely adsorbed by the wholly sesquioxidic clay fractions in Ferralsols in New Caledonia, and that P availability was positively related to organic matter.

In this study we use Hedley-type fractionation to examine the effects of the incipient ferralisation and the sesquioxides on the forms, quantities and retention of soil P in relation to sesquioxides and organic matter in the soils of a topo- and chrono-sequence in the tropical environment of Green Island, Taiwan. An earlier pedogenic study showed that the highest and oldest members of this sequence are weakly ferralitic, with more intense weathering and leaching and fewer argillic features than the younger soils downslope (Jien et al. 2016). We hypothesise that the older soils have a greater capacity for P sorption, that the sorbed P becomes less labile as it becomes more occluded, and that these changes are associated with increasing contents and crystallinities of sesquioxides as the soils age.

Methods

Study site and soils

Green Island, also known as Ludao, (22.6 N, 121.4 E), lies about 30 km off the south-eastern coast of Taiwan (Fig. 1); it has a mean temperature of 23.5 °C and mean precipitation of about 2500 mm. The original forest vegetation in this island has been heavily disturbed by wildfire and human activities. A large-scale afforestation effort was conducted in the 1960s, and consequently most of the area is now covered with secondary broadleaved forest. The dominant tree species in these broadleaf forests are Ardisia sieboldii, Schefflera octophylla, and Ficus nervosa.The island is underlain by Miocene and Pliocene andesitic-basaltic pyroclastic deposits and lava flows. The topography consists of irregular low hills with an altitudinal series of discontinuous, gently sloping benches (Fig. 1). There has been no volcanic activity for about two million years, but seismic activity continues and the benches appear to be formed in still- stands of spasmodic seismic uplift (Huang et al. 2012). Reefs developed along the coast during Quaternary still-stands, and now form coral benches at about 10 and 30 m above sea level (Fig. 1). These are distinct from the higher benches located on volcanic parent materials. Chen and Liu (1992) estimated the ages of the seven terraces they identified on Green Island as: about 80 ka for the 245–255 m level, 70 ka (190–200 m), 60 ka (165–175 m), 50 ka (140–150 m), 40 ka (80–90 m), 33∼35 ka (20–40 m) and < 5.5 ka (2–15 m). Progression in the degree of weathering of the benches with altitude has given rise to a chrono-sequence of soils of increasing ferralisation (Jien et al. 2016).

P sorption in the coral-derived soils on the lower benches is not considered in detail, as it is determined by calcareous reactions, rather than by sesquioxide sorption. In the sesquioxidic soils on the benches at 50 m and above, pH and base saturation decline with altitude and age. The subsoil matrix became more intensely red, with Munsell 2.5 YR, rather than 5 YR, hues predominant. Transient textural B horizons developed at intermediate altitudes but fade in the older soils upslope. The detail of pedological observation at each site was described elsewhere (Jien et al. 2016). They interpreted the changes as a trend of initial waxing and then waning of argillisation, through to incipient ferralisation. Taxonomically, the non-coral soils progress from Eutric Cambisol, through Acrisol, to incipient Ferralsol (FAO 2014), i.e. Eutrudept - Udalf - Udult - Udox in Soil Taxonomy (Soil Survey Staff 2014).

The soil on the 100 m bench appears to be anomalously eutrophic, with elevated pH and base saturation. This was attributed either to aeolian inputs of coral sand from the coast and lowest benches, or to a more mafic inclusion within the volcanic deposits.

Sesquioxide fractionation

The sesquioxide fractionations are for a single sample from each horizon. We determined total Fe and Al (Fet and Alt) with an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer (Rigaku ZSX Mini II XRF Analyzer, Japan). Free sesquioxides (Fed and Ald) were extracted with dithionite-citrate buffered with bicarbonate (Mehra and Jackson 1960). Amorphous sesquioxides (Feo and Alo) were extracted with ammonium oxalate at pH 3.0 (McKeague and Day 1966). The Fe and Al contents of the extracts were assayed by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP–AES) (JY124, Horiba Jobin–Yvon, France). Fed-Feo and Ald-Alo were taken as the crystalline fractions of the sesquioxides (Nagatsuka 1972; Maejima et al. 2002). The activity (Blume and Schwertmann 1969) or crystallinity (Maejima et al. 2002) ratios of the free sesquioxides were estimated by (Fed-Feo)/Fed and (Ald-Alo)/Ald.

P fractionation

P was fractionated for duplicate samples from each horizon, using a Hedley sequence of progressively more aggressive extractants (Table 1) applied sequentially to the same sample (Hedley et al. 1982; Levy and Schelsinger 1999). Before the sequential extractions, we determined the total P (Pt) by digesting a separate sample in concentrated H2SO4, 30% H2O2 and MgCl2 at 300 °C. The first stage in the sequential extraction removed labile P with a dilute salt (0.1 M KCl), rather than a resin (Elliot et al. 2002; Olila et al. 1997). The moderately labile P was extracted from the residue with 0.5 M NaHCO3. The residue from that was extracted with 0.1 M NaOH, for the P that is perceived to be sorbed on sesquioxides and stable organic matter and of low lability. We used the procedure of Tiessen and Moir (1993) to differentiate the inorganic and organic forms of P in both of the NaHCO3 and NaOH extracts. We first assayed initial P and took them as the inorganic (Pi) components. We digested the extracts at 200 °C with concentrated H2SO4 and 30% H2O2 to solubilise the organic P. The assayed P in these digests was taken as the total P for that fraction, and the organic P (Po) was estimated by subtraction of Pi. The P in apatite or associated with calcareous particles was extracted with 1 M HCl. The final extraction was for residual P (Pr) using concentrated H2SO4 and 30% H2O2 and was aimed at the occluded P with severely restricted or zero lability. The P concentrations in all extracts and digests were assayed colourimetrically by the malachite green procedure (Lajtha et al. 1999). The sums of the extracts exceed the initial Pt values throughout, giving apparent extraction values in excess of 100%. This suggests that the initial non-sequential XRF determination of total P (Pt) from the untreated fine earth was only partially effective.

Data analyses

The laboratory procedures for the fractionations of both sesquioxides and P require substantial time and effort. The potential for replication in studies like this is therefore limited, and n values, degrees of freedom, and the power of statistical analyses are low. As there were only single values for each sesquioxide fraction for each horizon, we used the means of the duplicate values for the P fractions for the correlations. For the statistical analyses we used the A horizon samples as the topsoils and the samples from the horizons showing the greatest pedogenic development, i.e. the most argic in the mid-altitude soils and most rubefied in the upper bench soils, as the subsoils.

The effect of bench height rank (which is taken as a surrogate for relative soil age) on general soil characteristics and pedogenic maturity, was examined by one-way analysis of variance for the sesquioxides, clay, pH and organic matter against bench height.

To examine for possible soil maturity trends in the sesquioxide and P variables, they were Spearman rank-based correlated against bench height/relative age. This was initially done for the whole data set, and then with the lower bench coral soils excluded.

To examine the associations between the sesquioxide and P variables, it was possible to estimate Pearson value-based correlations for all samples from the non-coral soils, and then separately for topsoils and for diagnostic subsoil horizons. All analyses were conducted using the Python sciPy, numPy, Pandas, and matplot.lib software packages language (Bezanson et al. 2017; https://www.scipy.org/citing.html).

Results

Sesquioxides

The initial one-way analyses of variance for Fed, Feo, Fed-Feo, Fed-Feo/Fed, Ald, and Ald-Alo against bench height rank are highly significant (p < 0.001), but only because of the substantial differences between the coral soils on the lower benches and the non-coral soils upslope. As our focus is on the effects of sesquioxides in the ferralisation chronosequence, further analyses are restricted to the non-coral soils on the benches at 50 m and above.

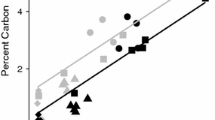

Total contents of iron (Fet) were moderate to high (mostly > 50 g kg−1), with highest values in the oldest soil, Pedon 240 (Table 2), but the Spearman correlation with bench height rank is not significant. The contents of free pedogenic iron (Fed) are moderate (> 20 g kg−1) throughout, but the intensity of iron weathering (Fed/Fet) is high, with Fed accounting for well over half of the total Fet. Iron weathering intensity (Fed/Fet) increases slightly and erratically with bench height (Fig. 2) but the Spearman correlation is not significant. Within profiles, Fe weathering is most intense in the diagnostic subsoil argic (argillic) or ferralic (oxic) B horizons, with lower values in both the topsoils and weathering C horizons. Contents of amorphous Fe (Feo) are low throughout, with a gradual decrease from 50 m up to 170 m, but are somewhat higher in the soils on the 190 and 240 m benches (Fig. 2). The low proportions of amorphous Feo imply that bulk of the free Fe (Fed) is crystalline, shown by the high crystallinity ratios ((Fed–Feo)/Fed) throughout, with the highest values in the oldest soils at 240 m, and the significant Spearman correlation (r = 0.504, p < 0.01) with bench height.

Total contents of aluminium (Alt) were similar to those for Fet (Table 2), and the Spearman correlation with bench height for the non-coral soils is also not significant. However, the weathering of Al follows a different trajectory from that of Fe, and the proportion of the liberated Al that remains free Al (Ald) is lower than for Fe, and the weathering intensity (Ald/Alt) therefore appears to be lower (Fig. 2). However, some of the Al released by weathering appears to co-precipitate with labile Si to form secondary aluminosilicates, particularly those with gibbsite interlayers, and some crystallizes out as gibbsite, particularly in topsoils (Jien et al. 2016). Aluminium in these forms does not register in the Ald values. The contents of amorphous Al (Alo) are low, slightly lower than those of Feo, and show no discernible altitudinal trend. The crystallinities of the free Ald ((Ald–Alo)/Ald) are high but substantially less than those for Fed, but the Spearman correlation with bench height rank is highly significant (r = 0.641, p < 0.001). However, apart from crystallinity, the associations of the sesquioxide indicators of ferralisation with bench height/age are erratic, and the original designation of the ferralisation trend as ‘incipient’ was correct (Jien et al. 2016).

P fractions

Total content of P (Pt) is higher in the topsoils than in the diagnostic subsoil horizons (Table 3), probably due to biotic recycling (Shiau et al. 2018). Total P values rise again with depth in some saprolitic C horizon. Comparison of the diagnostic subsoil horizons in the non-coralline soils show substantial differences in Pt between profiles, but no altitudinal trend. The differences are attributed to minor but variable aeolian inputs of coral material from downslope and to lithological variations in the volcanic parent materials.

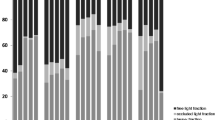

Although labile P, as extracted with KCl, is low throughout, values are consistently slightly higher in the topsoils, due to biotic recycling. The levels of Pi in the moderately labile NaHCO3 extracts are moderate, and are consistently lower than those from the NaOH extracts. The organic components of the NaOH extracts are consistently larger than the inorganic, by an order of magnitude or more. The preponderance of organic over inorganic components is also apparent in the NaHCO3 extracts, but the differences are less marked (Fig. 3). There are substantial quantities of residual Pr. As in the other fractions, values are higher in the topsoils than in the diagnostic subsoil horizons, suggesting that even the least labile P is substantially organic. Pr values increase with bench height, indicating a moderate increase in P sequestration with age.

Although the coralline soils are not the main focus of this study, it is worth noting that their labile KCl-P values are as low as those in the non-coral soils, but their NaHCO3-P and NaOH-P values are considerably lower. They also have higher values in the topsoils than the subsoil, and a predominance of organic over inorganic forms. As expected, the P associated with calcareous soil components, as extracted with dilute HCl, is an order of magnitude greater than in the non-coral soils. Although lower than in the non-coral soils on the higher benches, residual Pr values are surprisingly substantial.

P associations with sesquioxides

The Pearson correlations of the P fractions with the sesquioxides and other soil constituents for all of the non-coral samples (Table 4) show that the predominant organic forms of P in the NaHCO3 and NaOH extracts are significantly correlated with amorphous Feo and Alo. The importance of the amorphous sesquioxides is also apparent in the significant negative correlations for all of the topsoil and subsoil NaHCO3-Po and NaOH-Po extracts with the crystallinity of the free iron ((Fed–Feo)/Fed) and, to a lesser extent, with that of free aluminium ((Ald – Alo)/Ald). The inorganic P fractions are weak and correlated only with the crystallinities of Ald and Fed. The other sesquioxide variables, i.e. totals and total free contents, hardly register as significant correlates with any of the P fractions.

Repeating the correlations for topsoils and the diagnostic subsoil horizons separately reduces the n values, degrees of freedom and significance of the correlations. However, separating the different parts of the profiles clarifies the P relationships, and r values are higher than for the mixed data (Table 4). The pattern of correlations in the topsoils differs from that in the mixed data. The inorganic component of the labile NaHCO3 extractable fraction is highly and significantly correlated with crystalline Fed and Ald. The correlation of the organic component of the same fraction with Feo has a high r value but only weak significance. There are no significant correlations with soil organic carbon.

The pattern of correlations in the subsoil is similar to that for the mixed data. This is to be expected as subsoil values make up most of the mixed data. The organic component of the NaHCO3 P fraction is correlated highly and significantly positively with Feo and Alo, and highly and significantly negatively with the crystallinity of the free iron ((Fed–Feo)/Fed). However, there is no significant correlation with the crystallinity of the free Ald. As in the topsoils, there are no significant correlations with soil organic carbon, but the inorganic component of the NaHCO3 extract has a high and significant negative correlation with clay content in topsoils.

Discussion

A study in Java showed that P retention is a serious problem for young volcanic soils, even where highly weathered and tending to ferralic (Sukarman et al. 2020). The chemical and mineralogical attributes of the sesquioxidic soils of Green Island indicate significant, if still incipient ferralisation. However, the soils straddle the middle regions of the Walker and Syers (1976) pedo-senility paradigm, with P being sequestered in both organic and mineral forms. Together with the slight rises of Pt in some saprolitic horizons that may be due to traces of unweathered apatite (Nezata et al. 2007), this suggests that the P-sequestration trajectory has progressed less that of the chemical and mineralogical indicators.

Nonetheless substantial proportions of the soil P are sequestered in the inorganic NaOH and residual fractions (Fig. 3; Table 4). These inorganic subfractions are correlated with the age-related increasing crystallinities of the free sesquioxides. It is assumed this P is strongly adsorbed onto, and occluded into the particles of the accreting and increasingly crystallised free sesquioxides (Walker and Syers 1976). This P is likely to be sequestered for long periods, possibly >105 years, as its recycling is mainly affected by geological-scale weathering (Yang et al. 2013).

As quantities of highly available KCl-extractable P are very low, it appears that the limited quantities of labile P reside mainly in the substantial organic subfractions of the NaHCO3 and, to a limited extent, NaOH extracts. The preponderance of organic subfractions in these extracts has been noted in other tropical soils and coastal sand dune forest soils (Lin et al. 2018; Mirabello et al. 2012; Turner and Engelbrecht 2011). The importance of cryptic organic matter, the dark colours of which are masked by the intense rubefaction of the free iron sesquioxides, has been noted in deep ferralitic soils elsewhere in the tropics (Harper and Tibbett 2013). In our results, these P subfractions are not significantly correlated with soil organic carbon, and this P appears not to be simply adsorbed onto or incorporated into the chemical structures of free organic matter. In our study, these subfractions are correlated with amorphous Feo and Alo, even though these account for small proportions of the total free Fe and Al (Agbenin 1994; Singh and Gilkes 1991) (Fig. 2). These organic subfractions of P therefore appear to be sorbed onto and incorporated into complexes of organic matter and amorphous sesquioxides, especially Alo (Wang et al. 2019). This P is more available than that associated with crystallising sesquioxides, but its recycling depends on the dynamics of the complexes, and the rate at which the organic components are decomposed (Barthes et al. 2008; Hernandez-Soriano 2012).

Reported turnover rates of Al-organo complexes vary considerably but the more stable seem to range in age from 500 to 5000 years (Hagerty et al. 2014; Lützow et al. 2008; Mahia et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2017). This makes the P within such complexes as unavailable over the life spans of individual trees, but some may participate in the centennial and millennial nutrient cycling of stable forests and affect succession trajectories.

Conclusions

Soil macromorphology, chemistry and mineralogy indicate incipient ferralisation in the soils of the chronosequence, but the parallel trends in P sequestration are weak. Some of the P is sorbed into Al-organo complexes, which vary in their turnover rates. Some of the complexes persist for millennia and the recycling of their sorbed P is likely to be very slow. Although the increase in the quantities of sesquioxides with age are only slightly significant, their crystallinities increase with age. P occluded within the crystalline forms is likely to be completely immobilised, and to be recycled only within time scales of geological weathering. The current dynamics of P in the soils of the Green Island chronosequence appear to be mainly determined by complexes of amorphous Al and organic matter.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- Ald :

-

Free form aluminium oxide

- Alo :

-

Amorphous aluminium oxide

- Alt :

-

Total aluminium

- Fed :

-

Free form iron oxide

- Feo :

-

Amorphous iron oxide

- Fet :

-

Total iron

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- Pi :

-

Inorganic P

- Po :

-

Organic P

- Pr :

-

Residual P

- Pt :

-

Total P

- XRF:

-

X-ray fluorescence

References

Adejumo MA, Omueti JAI (2016) Phosphorus sorption characteristics in soils of basement complex and sedimentary parent materials in south western Nigeria. Agri Biol J N Am 7:153–162

Agbenin JO (1994) Phosphorus fractions, mineralogy and transformations in soils of two catenary sequences from northeastern Brazil. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Saskatchewan

Baillie IC, Ashton PS, Court MN, Anderson JAR, Fitzpatrick EA, Tinsley J (1987) Site characteristics and the distribution of tree species in mixed Dipterocarp forest on tertiary sediments in central Sarawak, Malaysia. J Trop Ecol 3:201–220

Barthes BG, Kouakoua E, Larre-Larouy MC, Razafimbelo TM, de Luca EF, Azotonde A, Neves CSVJ, de Freitas PL, Feller CL (2008) Texture and sesquioxide effects on water-stable aggregates and organic matter in some tropical soils. Geoderma 143:14–25

Baumann K, Shaheen SM, Hu YF, Gros P, Heilmann E, Morshedizad M, Wang JX, Wang SL, Rinklebe J, Leinweber P (2020) Speciation and sorption of phosphorus in agricultural soil profiles of redoximorphic character. Environ Geochem Health 42:3231–3246

Bezanson J, Edelman A, Karpinski S, Shah VB (2017) Julia: a fresh approach to numerical computing. SIAM Review 59(1):65–98

Blume HP, Schwertmann U (1969) Genetic evaluation of profile distribution of aluminum, iron, and manganese oxides. Soil Sci Soc Am Proc 33:438–444

Bortoluzzi EC, Perez CAS, Ardisson JD, Tiecher T, Caner L (2015) Occurrence of iron and aluminum sesquioxides and their implications for the P sorption in subtropical soils. Appl Clay Sci 104:196–204

Cajuste LJ, Laird RJ, Cruz D, Cajuste JrL (1994) Phosphate availability in tropical soils as related to phosphorus fractions and chemical tests. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 25:1881–1889

Chen YG, Liu TK (1992) Vertical crustal movement of a tectonic uplifting volcanic island – Lutao. J Geol Soc China 35:231–246

Daniela D, Elsenbeer H, Turner BL (2010) Phosphorus fractionation in lowland tropical rainforest soils in central Panama. Catena 82:1189–1125

Dubus IG, Becquer T (2001) Phosphorus sorption and desorption in oxide-rich Ferralsols of New Caledonia. Aust J Soil Res 39:403–414

Elliot HA, O’Connor GA, Brinton S (2002) Phosphorus leaching from biosolids-amended sandy soils. J Environ Qual 31:681–689

FAO (2014) World Reference Base for Soil Resources A Framework for International Classification, Correlation and Communication. World Soil Resources Reports 106. Food and Agriculture Organisation of United Nations, Rome

Ghani MO, Islam MA (1946) Phosphate fixation in acid soils and its mechanism. Soil Sci 62(4):293–306

Guo F, Yost RS, Hue NV, Evensen CI, Silva JA (2000) Changes in phosphorus fractions in soils under intensive plant growth. Soil Sci Soc Am J 64:1681–1689

Hagerty SB, van Groenigen KJ, Allison SD, Hungate BA, Schwartz E, Koch GW, Kolka RK, Dijkstra P (2014) Accelerated microbial turnover but constant growth efficiency with warming in soil. Nat Clim Chang 4:903–906

Harper RJ, Tibbett M (2013) The hidden organic carbon in deep mineral soils. Plant Soil 368:641–648

Hedley MJ, Stewart JWB, Chauhan BS (1982) Changes in inorganic and organic soil-phosphorus fractions induced by cultivation practices and by laboratory incubations. Soil Sci Soc Am J 46:970–976

Hernandez-Soriano MC (2012) The role of aluminium-organo complexes in soil organic matter dynamics. In: Hernandez-Soriano MC (ed) Soil Health and Land Use Management, Rijeka. pp 17–32

Huang HH, Shyu JBH, Wu YM, Chang CH, Chen YG (2012) Seismotectonics of northeastern Taiwan: Kinematics of the transition from waning collision to subduction and post collisional extension. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 117:B01313

Jien SH, Baillie I, Huang WS, Chiu CY (2016) Incipient ferralization and weathering indices along a soil chronosequence in Taiwan. Eur J Soil Sci 67:583–596

Karim MI, Adams WA (1984) Relationships between sesquioxides, kaolinite, and phosphate sorption in a catena of Oxisols in Malawi. Soil Sci Soc Am J 48:406–409

Kitayama K, Aiba SI, Takyu M, Majalap N, Wagai R (2004) Soil phosphorus fractionation and phosphorus-use efficiency of a Bornean tropical montane rain forest during soil aging with podozolization. Ecosystems 7:259–274

Lajtha K, Driscoll CT, Jarrell WM, Elliott ET (1999) Soil phosphorus. Characterization and total element analysis. In: Robertson GP, Coleman DC, Bledsoe CS, Sollins P (eds) Standard soil methods for long-term ecological research. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 115–142

Levy ET, Schlesinger WH (1999) A comparison of fractionation methods for forms of soil phosphorus. Biogeochemistry 47:25–38

Lin CW, Tian G, Pai CW, Chiu CY (2018) Characterization of phosphorus in subtropical coastal sand dune forest soils. Forests 9:710

Lützow Mv, Kögel-Knabner I, Ludwig B, Matzner B, Flessa H, Ekschmitt K, Guggenberger G, Marschner B, Kalbitz K (2008) Stabilization mechanisms of organic matter in four temperate soils: Development and application of a conceptual model. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 171:111–124

Maejima Y, Nagatsuka S, Higashi T (2002) Application of crystallinity ratio of free iron for dating soils developed on the raised coral reef terraces of Kikai and Minami-Daito islands, southwest Japan. Quat Res (Daiyonki-Kenkyu) 41:485–493

McKeague JA, Day JH (1966) Dithionite and oxalate extractable Fe and Al as aids in differentiating various classes of soils. Can J Soil Sci 46(1):13–22

Mahía J, Pérez-Ventura L, Cabaneiro A, Díaz-Raviña M (2006) Soil microbial biomass under pine forests in the north-western Spain: Influence of stand age, site index and parent material. For Syst 15:152–159

Maranguit D, Guillaume T, Kuzyakov Y (2017) Land-use change affects phosphorus fractions in highly weathered tropical soils. Catena 149:385–393 ()

Mehra OP, Jackson ML (1960) Iron oxides removed from soils and clays by a dithionite-citrate system buffered with sodium bicarbonate. Clays Clay Miner 7:317–327

Metzger WH (1941) Phosphorus fixation in relation to the iron and aluminium of the soil. Agron J 33:1093–1099

Mirabello MJ, Yavitt JB, Garcia M, Harms KE, Turner BL, Wright SJ (2012) Soil phosphorus responses to chronic nutrient fertilisation and seasonal drought in a humid lowland forest, Panama. Soil Res 51(3):215–221

Nagatsuka S (1972) Studies on genesis and classification of soils in warm-temperate region of Southwest Japan. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 18(4):147–154

Nezata CA, Blum JD, Yanai RD, Hamburg SP (2007) A sequential extraction to determine the distribution of apatite in granitoid soil mineral pools with application to weathering at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, NH, USA. Appl Geochem 22:2406–2421

Olila OG, Reddy KR, Stites DL (1997) Influence of draining on soil phosphorus forms and distribution in a constructed wetland. Ecol Eng 9:157–169

Richter DD, Allen HL, Li J, Markewits D, Raikes J (2006) Bioavailability of slowly cycling soil phosphorus: major restructuring of soil P fractions over four decades in an aggrading forest. Oecologia 150:259–271

Saunders WMH (1965) Phosphate retention by New Zealand soils and its relationship to free sesquioxides, organic matter, and other soil properties. New Zealand J Agri Res 8:30–57

Shiau YY, Pai CW, Tsai JY, Liu WC, Yam RSW, Chang SC, Tang ST, Chiu CY (2018) Characterization of phosphorus in a toposequence of subtropical perhumid forest soils facing a subalpine lake. Forests 9(6):294

Singh B, Gilkes RJ (1991) Phosphorus sorption in relation to soil properties for the major soil types of South-Western Australia. Soil Res 29:603–618

Sukarman, Barus PA, Gani RA (2020) Soil mineralogy and chemical properties as a basis for establishing nutrient management strategies in volcanic soils of Mount Ceremai, West Java. J Degraded Mining Lands Management 8:2419–2430

Syers JK, Evans TD, Williams JDH, Murdock JT (1971) Phosphate sorption parameters of representative soils from Ro Grande do Sul, Brazil. Soil Sci 112:267–275

Tiessen H, Moir JO (1993) Characterisation of available P by sequential extraction. In: Carter MR (ed) Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis. Lewis Publisher, Boca Raton, pp 75–86

Turner BL, Engelbrecht BMJ (2011) Soil organic phosphorus in lowland tropical rain forests. Biogeochemistry 103:297–315

Turner BL, Condron LM (2013) Pedogenesis, nutrient dynamics, and ecosystem development: the legacy of TW Walker and JK Syers. Plant Soil 367:1–10

Udo EJ, Uzu FO (1972) Characteristics of phosphorus adsorption by some Nigerian soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 36:879–883

Vitousek P (2004) Nutrient cycling and limitation. Hawai’i as a model system. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Walker TW, Syers JK (1976) The fate of phosphorus during pedogenesis. Geoderma 15:1–19

Wang XM, Phillips BL, Boily JF, Hu YF, Hu Z, Yang P, Feng XG, Xu WQ, Zhu MQ (2019) Phosphate sorption speciation and precipitation mechanisms on amorphous aluminium hydroxide. Soil Syst 3(20):1–17

Wright SJ, Yavitt JB, Wurzburger N, Turner BL, Tanner EVJ, Sayer EJ, Santiago LS, Kaspari M, Hedin LO, Harms KE, Garcia MN, Corre MD (2011) Potassium, phosphorus or nitrogen limit root allocation, tree growth, or litter production in a lowland tropical forest. Ecol 92(8):1616–1625

Wu SP, Chen ZS (2005) Characteristics and genesis of Inceptisols with placic horizons in the subalpine forest soils of Taiwan. Geoderma 125:331–341

Xu X, Schimel JP, Janssens IA, Song X, Song C, Yu G, Sinsabaugh RL, Tang D, Zhang X, Thornton PE (2017) Global pattern and controls of soil microbial metabolic quotient. Ecol Monogr 87:429–441

Yang X, Post WM, Thornton PE, Jain A (2013) The distribution of soil phosphorus for global biogeochemical modelling. Biogeosciences 10:2525–2537

Yusrani FA (2010) The Relationship between Phosphate Adsorption and Soil Organic Carbon from Organic Matter Addition. J Trop Soils 15(1):1–10

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Academia Sinica, and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 109-2313-B-001-014-MY2). We are grateful for constructive comments from Brian Kerr on an early version of this submission. We acknowledge the use of the ‘Ecosystem Services Databank and Visualisation for Terrestrial Informatics’ facility, supported by NERC (NE/L012774/1).

Funding

Academia Sinica, and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CYC and IB originally formulated the idea and developed methodology. IB and CYC wrote the manuscript with inputs from other authors. SHJ performed soil survey. LH and SH helped in analyzing and interpreting data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for publication

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiu, CY., Baillie, I., Jien, SH. et al. Sequestration of P fractions in the soils of an incipient ferralisation chronosequence on a humid tropical volcanic island. Bot Stud 62, 20 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-021-00326-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40529-021-00326-5