Abstract

The paper studies the effects of the real exchange rate (RER) on capital accumulation in Mexico in the period since the late 1980s. By testing for the existence of potential asymmetries, the paper seeks to clarify some of the controversies surrounding the subject. It shows the RER’s long-run effects to be qualitatively symmetric but quantitatively asymmetric; thus, while appreciations slow accumulation, depreciations accelerate it, but to a lesser degree. Depreciations, moreover, have dynamically asymmetric effects, expansionary in the long run but contractionary in the short run. The effects are derived from non-linear autoregressive distributed lag models for the private capital accumulation rate in the manufacturing, tradables, and non-tradables sectors, and for the aggregate level of private fixed investment. The results help to reconcile the contradictory conclusions reached by previous studies of Mexico, and to clarify the potential role of the real exchange rate as either barrier or engine of growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

According to recent development studies, a depreciated real-exchange-rate (RER) level can increase the rate of economic growth, particularly so in developing countries and in the medium run. But although many studies have supported this proposition, others have questioned it: a depreciated RER may facilitate but not ensure faster growth; or appreciations may hurt growth while depreciations play a more neutral role; or both appreciations and depreciations relative to an equilibrium level may in fact decelerate growth.

Mexico, with its history of wide RER fluctuations and protracted appreciation trends, has not been immune to these controversies. But while different studies have reached contradictory results, none has tried to establish why this is so. The possible role of asymmetries, in particular, has not been properly studied. While there may be some consensus around the negative growth effects of appreciations, for example, the possibility of positive effects from depreciations remains more controversial.

The present paper contributes to the literature on RER and growth with a detailed study of the Mexican case. Applying a methodology specifically designed to test for asymmetries, the paper shows the RER effects on capital accumulation in Mexico to be qualitatively symmetric but quantitatively asymmetric; thus, while appreciations indeed are detrimental to capital accumulation—particularly in manufacturing and the tradables sector—depreciations are beneficial, but to a lesser degree. The effects, moreover, are dynamically asymmetric, with depreciations leading to expansions in the long run but contractions in the short run. The results point to a possible explanation of the contradictory conclusions reached by previous studies of Mexico. Because of the country’s rich RER experience and its puzzling growth facts, it is hoped that the results will also contribute to a better understanding of the international evidence.

The analysis relies on the estimation of non-linear error-correction autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) models. Recently developed by Shin et al. (2014) as an extension of the bounds-testing approach of Pesaran et al. (2001), the non-linear ARDL model can be used to explore in a rigorous and flexible way the multiple asymmetries that may arise out of changes in the RER. Based on this model, the paper presents two sets of estimations. In the first one, the dependent variable is the capital accumulation rate (the growth rate of the real net capital stock) in the private, non-residential sector of the Mexican economy. Using annual series from Mexico’s KLEMS database for the period 1992–2015, the paper estimates separate equations for manufacturing, tradables as a whole, and non-tradables. The results shed light on the role of tradables in the transmission of the RER to economic growth, a frequently mentioned but not much studied channel in the literature.

In the second set of estimations, the dependent variable is the aggregate level of private investment (gross fixed capital formation in the private sector). Because of data restrictions, this second set of estimations cannot distinguish between tradables and non-tradables. But the higher frequency of the investment series—with quarterly observations for the period 1988–2016—allows a detailed analysis of trajectories based on the dynamic multipliers of the non-linear ARDL model. The multipliers trace the path followed by investment after a permanent change in the RER, thus revealing possible asymmetries between the short and long run.

The paper proceeds as follows. After a brief review of the literature in Sect. 2, Sect. 3 describes the data and methodology, Sect. 4 presents the results—first for the capital accumulation rate, then for the investment level—and Sect. 5 concludes. An Appendix details data sources and definitions and provides the unit-root test results—showing a combination of stationary and non-stationary variables—that motivate the choice of estimation methodology.

2 Literature review

A key proposition from the recent development literature is that a higher (depreciated) RER level can raise the rate of economic growth, particularly so in developing countries and in the medium run. Typically, these studies—launched by Gala (2008) and Rodrik (2008)—exploit country panels containing 5-year averages of data. To make the data comparable across countries, the studies often measure the RER in relation to an equilibrium value, with the latter calculated either as the RER adjusted for the Balassa–Samuelson effect or alternatively as the RER consistent with internal and external equilibrium a la Nurkse. As noted below, though, calculating an equilibrium RER may create uncertainty about the robustness of results, and therefore other studies have used the actual RER level instead.Footnote 1

According to one view, a depreciated RER level raises the rate of economic growth by redistributing income from wages to profits, thus increasing the economy’s saving and investment rates (see for example Gluzmann et al. 2012). The dominant theoretical approach (as articulated for example by Rodrik 2008), however, takes a more disaggregated view and argues that a depreciated RER level affects the rate of economic growth by its differentiated effects on the tradables and non-tradables sectors. In particular, a depreciation increases the relative price and profitability of tradables, stimulating its expansion. Since the tradables sector is characterized by the use of modern, capital-intensive technology, its expansion leads to higher rates of capital accumulation and productivity growth for the economy as a whole (see Rapetti 2016 for a discussion of the RER’s growth channels, and Ibarra 2016 for a review of the literature).

But while many studies have confirmed the RER’s positive growth effects, others have questioned them. Typically, doubts are framed in terms of potential asymmetries between the effects of appreciations and depreciations (or alternatively between those of overvaluation and undervaluation). The asymmetries can be of a quantitative or qualitative nature. A qualitative asymmetry arises when in the growth equation the estimated RER coefficient switches sign depending on whether the currency is appreciating or depreciating. A quantitative asymmetry, in contrast, arises when the estimated value but not the sign of the RER coefficient changes between appreciations and depreciations. Examples of both types of asymmetry are noted below.

Rodrik (2008) tested for the existence of asymmetries but found no significant evidence for it: in his growth equations the estimated effect of the RER remains mostly unchanged across different levels of undervaluation. Berg and Miao (2010) include in their growth equations a series of dummies to separate the effects of overvaluation and undervaluation, and find no evidence of a switch in the sign of the estimated coefficients. Béreau et al. (2012) reach a similar conclusion within a panel smooth transition regression model.

Other studies differ. Eichengreen (2008) and Di Nino et al. (2011) argue that a depreciated currency should be considered more a facilitating condition than a sufficient one to achieve faster growth rates. Razin and Collins (1997), Aguirre and Calderón (2006), and Nouira and Sekkat (2012) find negative effects from overvaluation but neutral or even negative effects also from undervaluation, thus exemplifying a case of qualitative asymmetries. In some of these studies, the switch in sign reflects the presence of non-linearities, according to which a moderate degree of undervaluation raises growth but an extreme one depresses it. Recently, Missio et al. (2015) showed this type of non-linearity in panel regressions for the output level rather than its growth rate. These asymmetries, however, depend on the presence of extreme RER values and leave open the question of whether they may arise under more normal RER circumstances. Following a different approach, Schröder (2013) concludes that both undervaluation and overvaluation are detrimental to growth (a case again of qualitative asymmetry), a finding he attributes to his approach of calculating an individual Balassa–Samuelson effect by country instead of the homogenous cross-country effect calculated by Rodrik (2008) and many others. The finding calls attention to how the results of growth regressions may be sensitive to the way the equilibrium RER is calculated.

As mentioned above, the RER’s growth effects are typically understood to operate through either faster capital accumulation or stronger productivity growth. Possible asymmetries in these channels have been considered by a few studies. Oreiro and Araujo (2013) estimate a quadratic function for capital accumulation in Brazil and find that a real depreciation has a positive effect on accumulation, which however turns negative at high RER levels.Footnote 2 Razmi et al. (2012) divide their sample of developing countries into those with undervalued and overvalued currencies and estimate separate equations for the growth rate of investment. They find that the (negative) effect of overvaluation may be larger in absolute terms than the (positive) effect of undervaluation, thus illustrating a case in which the RER effects are qualitatively symmetric but quantitatively asymmetric. Mbaye (2013) calculates separate indices of undervaluation and overvaluation, and shows the effects of undervaluation on total factor productivity growth to be somewhat larger than those of overvaluation, particularly so in developing countries; whether the difference is statistically significant is not tested, though.

Turning to Mexico, several studies have provided conflicting evidence on the RER’s growth effects. For aggregate output, studies finding contractionary effects include Kamin and Rogers (1997), Garcés (2008), and López et al. (2011); Galindo and Ros (2008), in contrast, show expansionary long-run effects. For aggregate investment, Caballero and Lopez (2012) find contractionary effects, while Ibarra (2010, 2015) shows the opposite ones. In an intermediate position, Blecker (2009) found a negative direct effect on the investment rate, which however was mostly offset by a positive indirect effect operating through the output growth rate. While the contractionary effects are typically motivated by the rising costs of imported inputs and higher payments of dollar-denominated debt—factors that may be particularly relevant for firms in the non-tradables sector—the expansionary ones are attributed to greater profit margins in the tradables sector, or alternatively to a relaxation of the external constraint on growth thanks to greater price competitiveness. But with the exception of Galindo and Ros (2008), who show the existence of contractionary effects in separate short-run equations, none of these studies applied a methodology to detect possible asymmetries.

As in other areas of research, the conflicting results may be explained by the use of different methodologies, the focus on different periods—particularly in Mexico, which transited in the mid-1980s from having a heavily regulated trade regime to a mostly liberalized one, a transition that may have altered the way macroeconomic variables adjust to changes in relative prices—and the way the estimations handle the impact of the financial crises often linked to large depreciations. Because of the latter factor, some of the estimates may be picking up contractionary effects of a short-run nature, a possibility that arises from the way the equations are sometimes specified.

Thus, while the recent international research relates the rate of economic growth to the level of the RER, studies of Mexico have estimated relationships between the level of the RER and the level (rather than the growth rate) of output, the first difference of both variables, or even the first difference of the RER and the level of output (as in some of the works cited by Kamin and Rogers 1997). As an important advantage, the econometric methodology to be applied in the present paper allows for clearly distinguishing between short- and long-run effects, and for doing so separately for depreciations and appreciations, all within a single estimated model. As we will see, this contributes to reconciling the apparently contradictory conclusions reached in previous research.

3 Data and methodology

To test for the presence of asymmetries, the estimations in the paper follow the non-linear ARDL approach of Shin et al. (2014). For this, the peso’s RER series was split into its appreciation and depreciation components as follows:

where RER0 is an initial RER value, and RERD and RERA are partial sum processes of positive (depreciation) and negative (appreciation) RER changes: \({\text{RERD}}_{t} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^{t} { \text{max} }\left( {\Delta {\text{RER}}_{j} ,0} \right)\;{\text{and}}\;{\text{RERA}}_{t} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{j = 1}^{t} { \hbox{min} }\left( {\Delta {\text{RER}}_{j} ,0} \right).\)

In contrast to panel-data studies which, for the reasons noted in Sect. 2, frequently measure the RER in relation to an estimated equilibrium level, the present paper uses the actual RER series to calculate RERD and RERA (see Bahmani-Oskooee and Mohammadian 2016 for a similar approach). This makes the interpretation of the estimation results more transparent, as the latter do not depend on the choices—regarding methodology, estimation period, explanatory variables—that must be made to estimate an equilibrium RER level.Footnote 3 It is not clear, moreover, which definition of equilibrium is the relevant one for an analysis of capital accumulation—as opposed to for example an assessment of external balance, which is more firmly established in the literature. In any event, the highly significant estimates reported below support the approach followed in the present paper: real appreciations, for example, slow capital accumulation, which should not be the case if appreciations were an equilibrium phenomenon that reflected gains in productivity.

Figure 1 presents quarterly series for the RER and its components. Given the RER’s ample variability, the decomposition creates well-defined trends for both RERD and RERA. For the post-liberalization period 1988–2016—the focus of our analysis—the first difference of RERD contains 49 non-zero observations, while that of RERA contains 66. The number of non-zero observations is larger for RERA than for RERD, but not overwhelmingly so. The estimates reported below, therefore, do not seem open to the critique—raised for example by Nouira and Sekkat (2012)—that the results of growth regressions may be biased by the predominance of one RER regime over the other.Footnote 4

Real exchange rate and its components, 1980Q1–2016Q4. RER is the Bank of Mexico’s effective index, based on consumer price indices for 111 countries, where an increase means a real peso depreciation. RERD and RERA are partial sum processes of positive (depreciation) and negative (appreciation) RER changes. The series are expressed in natural logs times 100

Using the above decomposition, the paper presents two sets of estimations: one for the growth rate of the net private non-residential capital stock (or capital accumulation rate, for short), and the other for the level of gross private fixed capital formation (or private investment level). The estimations for the capital accumulation rate use the available annual series for the period 1990–2015, which after computing first differences and lags is reduced to 1992–2015. Given the relatively small number of observations (which however cover a long historical period), and to minimize the number of coefficients to be estimated, the estimations control only for the production growth rate.Footnote 5 On the plus side, the data—which were obtained from INEGI’s (Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics) KLEMS database—allow us to estimate separate equations for manufacturing, tradables as a whole, and non-tradables. Details on these data and the delimitation of sectors can be consulted in the Appendix.

The second set of estimations, those for the private investment level, use quarterly data for the period 1988–2016 (ending in the third quarter of the latter year), thus covering the entire period after the liberalization of the trade regime in Mexico. In this case, the large number and high frequency of observations allow us to control for a wide set of macroeconomic determinants of investment, and to carry out a detailed analysis of short-run effects and trajectories.

The investment series come from National Accounts. The estimations use the most up-to-date data, which are those based on the year 2008; these series, which begin in 1993, were completed with data taken from the 1980-based National Accounts. The spliced series are shown, as series A, in Fig. 2. These are the series used in the majority of estimations in the paper. For the overlapping period 1993–2007, however, preliminary exploration showed a large discrepancy between the 2008-based series and the also available 1993-based ones. Most notably, while the public investment series A declined markedly in the early 1990s and again during the late 1990s and early 2000s, the 1993-based series (series B in Fig. 2) remained flat. As a counterpart, private investment increased more sharply in series A than in series B. Given these differences, as a robustness exercise the paper will present alternative estimates from equations based on series B.

Private and public investment, alternative series, 1980Q1–2016Q3. Four-quarter moving averages based on constant-price data. Series A splice National Accounts (NA) data based on the years 1980 (from 1980Q1 to 1993Q1) and 2008 (from 1993Q2 to 2016Q3). Series B use 1993-based NA data from 1993Q2 to 2007Q4. The series are expressed in natural logs times 100

The ARDL model of Shin et al. (2014) extends to the non-linear case the error-correction bounds-testing approach of Pesaran et al. (2001). Among its main advantages, the approach allows the estimation of long-run relationships between the levels of variables that may be stationary or not, a feature of our dataset (see the unit-root test results in the Appendix).Footnote 6 It yields, within a single equation, estimates of both the long- and short-run coefficients—including the error correction one. It eliminates, through the inclusion of lags, the possible endogeneity bias in the estimation of the long-run coefficients (see Pesaran and Shin 1998). The non-linear version of the model, finally, detects possible asymmetries based not on extreme values of the RER but on its direction of change, that is, on whether the currency appreciates or depreciates.

To obtain the above results, the first step is to estimate an error-correction ARDL model allowing for non-linear RER effects as follows:

where g is the capital accumulation rate (in manufacturing, tradables as a whole, or non-tradables), RERD and RERA the RER’s depreciation and appreciation components, y the growth rate of real gross production, ρ the error-correction coefficient, d0 an intercept, e the residual, Δ the first-difference operator, and p = q the initial number of lags. Preliminary estimations showed that one lag was sufficient to pass the diagnostic tests. Finally, du stands for 0–1 dummies that capture transitory or permanent shifts in the intercept of some of the estimated equations, as explained below.

After simplifying the initial equation by removing the longest non-significant lags in the first-differenced variables, t and F tests are applied to the estimated coefficients to determine whether the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship between the variables can be rejected;Footnote 7 rejection requires the t (in absolute value) and F statistics to lie above the asymptotic upper critical values (or upper bounds) calculated by Pesaran et al. (2001) and the small-sample critical values calculated by Narayan (2005), respectively. If the latter conditions are met, the null hypothesis can be rejected irrespective of whether the variables are stationary or not—that is, whether they are integrated of order zero, one, or a combination. Finally, the estimated coefficients from the simplified version of (2a) can be used to form the long-run equation,

where the long-run coefficients are calculated as δi = − di/ρ, with i = 0, 1, 2, 3.

For the investment equations, the initial error-correction ARDL model took the form,

where PI is the real private investment level, the Z’s its k–2 potential determinants (in addition to the RER), and the initial number of lags was set to three (which would be equivalent to four lags in a traditional ARDL model in levels). The list of investment determinants includes the industrial production index or alternatively the gross domestic product (GDP, both intended to capture accelerator effects), public investment (to control for complementary or substitution effects), the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate (as components of the real interest rate, intended to capture the cost of credit), the monetary aggregate M3 as a percentage of GDP (to control for the credit channel), and the level of real manufactured exports (as an additional source of accelerator effects, given the pattern of export-led growth followed by the Mexican economy during the period). Some equations also include permanent intercept shifts, as explained below. After following the estimation procedure described above, Eq. (3a) can be used to derive the long-run equation,

where to avoid an unnecessarily large notation we use the same letters from the capital accumulation equations to denote the estimated coefficients.

The estimated coefficients δ1 and δ2 in Eqs. (2b) and (3b) measure the long-run effects of depreciations and appreciations. The effects may be asymmetric, either qualitatively or quantitatively. They will be qualitatively asymmetric when the sign of the effect depends on whether the currency is appreciating or depreciating, in which case δ1 and δ2 will have different signs or one of them may be zero.Footnote 8 The effects will be quantitatively asymmetric, in contrast, when only their size, but not their sign, depends on whether the currency appreciates or depreciates, in which case δ1 and δ2 will have the same sign but different estimated value. If δ2 > δ1 > 0, for example, the effects would be qualitatively symmetric: while a real appreciation slows capital accumulation, a real depreciation accelerates it. Quantitatively, however, the effects would be asymmetric, meaning that an appreciation would be more detrimental to capital accumulation than a depreciation would be beneficial to it. As shown by Shin et al. (2014), the statistical significance of the latter asymmetry can be tested by a Wald test.

In addition to testing for differences in long-run effects, a second type of asymmetry—namely, that between short- and long-run effects—can be explored by using the estimated coefficients on the first-differenced variables in Eq. (3a). Of particular interest is the possibility of a switch in coefficient signs as we move from the initial to the final lags. The often discussed possibility of expansionary depreciation effects in the long run, but with contractionary ones in the short run, for example, would correspond to a case in which δ1 > 0 in Eq. (3b) but with a predominance of negative b1 coefficients in the first lags of Eq. (3a).

To more easily detect a switch in sign, in Sect. 4.2 the estimated coefficients from Eq. (3a) will be used to calculate the path followed by investment after a permanent change in both RERD and RERA; this will make it visually straightforward to compare short- and long-run effects. The path will be obtained from the dynamic multipliers,

which define the dynamic adjustment of investment after a positive or negative change in the RER (see Shin et al. 2014 for details).

4 Estimation results

4.1 Capital accumulation equations

Table 1 presents estimated equations for the capital accumulation rate in manufacturing, tradables as a whole, and non-tradables in Mexico during the period 1992–2015. To pass the diagnostic tests, the equations include outlier year dummies for the crisis years 2009 and 1995 (plus 1994 in tradables), and also for 2013 (or 2012 in non-tradables). Without the dummies for the latter 2 years, the equations show abnormally large positive residuals; the residuals reflect a puzzling increase in the actual accumulation rate, which contrasts with the fall in the predicted rate in a context of slow production growth and real currency appreciation. The increase in the actual accumulation rate seems anomalous also in light of the deceleration of investment as reported in the National Accounts, and which will be further discussed below, in the estimation of the investment equations.

As a preliminary step, the equations in Table 1 include the actual RER series without decomposing it into RERA and RERD. According to the bounds-test results, the three equations can be interpreted as long-run relationships. Consistent with these results, the estimated error-correction coefficient is negative and highly significant in economic and statistical terms. Controlling for the accelerator effect, the equations show a positive correlation between the RER and capital accumulation in manufacturing and tradables, according to which a 10% higher RER level (that is, a 10% permanent depreciation) would tend to increase the accumulation rate by about 2.5% points. In non-tradables, in contrast, the RER coefficient is negative and smaller in absolute terms. The RER, therefore, affects the sectoral pattern of capital accumulation, with a higher RER level shifting accumulation from non-tradables to tradables.Footnote 9

Turning to our main results, Table 2a presents estimated equations that include the appreciation RERA and depreciation RERD series. In addition to the results for the different sectors, the last column in the table shows estimates for the whole economy. As shown in the table, the sign of the estimated coefficients on RERA and RERD differs across sectors but does not switch within each sector. Thus, the estimated coefficients are negative in non-tradables, but positive in manufacturing, tradables, and—reflecting the dominance of the latter sector—the whole economy. This implies that, qualitatively, the RER effects are symmetric: in manufacturing, tradables, and the economy as a whole, a depreciation accelerates capital accumulation while an appreciation decelerates it; in non-tradables the effects are the opposite but also symmetric: the accumulation rate falls with depreciations and rises with appreciations.Footnote 10

But while the RER effects are qualitatively symmetric, there is strong evidence that they are quantitatively asymmetric. In manufacturing and tradables, in particular, the estimated coefficients on RERA are visibly larger than those on RERD, a difference which according to a Wald test is statistically significant. A similar difference is observed for the whole economy, although with a weaker Wald test result. According to this difference, appreciations affect capital accumulation more strongly than do depreciations. In manufacturing, for example, while a 10% appreciation decreases the accumulation rate by 2.47% points, a similar 10% depreciation increases it by only 2.03 points. The difference is larger for tradables as a whole. In non-tradables, in contrast, the effects of appreciations and depreciations seem to be completely symmetrical.

The previous estimations were made under the implicit assumption that changes in the production growth rate have symmetrical effects on the accumulation rate. As a robustness exercise, the accumulation equations were re-estimated allowing for possible asymmetries in the effects of production growth. For this, the production growth rate was split into two series: one corresponding to a “high” growth rate, equal to the actual growth rate when this was above the average rate for the whole period, and equal to zero otherwise; and another one for a “low” growth rate, equal to the actual growth rate when this was below the average growth rate for the whole period, and to zero otherwise.Footnote 11 The new equations are shown in Table 2b. As can be seen, they have very good diagnostic test results and the bounds tests support their interpretation as long-run relationships; the error-correction coefficient in non-tradables, though, is too large (in absolute terms) and thus the equation must be taken with some caution.

The estimation results show clear evidence of asymmetric effects from the production growth rate: in manufacturing and tradables, the asymmetry consists of larger effects of low (including negative) growth rates on capital accumulation than those of high growth rates, while in non-tradables the opposite is true, with larger effects from high growth rates than those of low growth rates. Thus, in tradables for example, a relatively low production growth rate (or a negative one) tends to reduce the capital accumulation rate by more than it is increased by a high production growth rate. Note, however, that the new results do not affect the conclusions previously obtained for the RER: as in the original equations, we still observe that in manufacturing and tradables an appreciation tends to reduce the capital accumulation rate by more than a depreciation tends to increase it.

4.2 Investment equations

Next, we consider estimates for the aggregate investment level. Initially two sets of estimations are presented, one which allows for a permanent downward intercept shift after the peso crisis of 1994–1995 (plus an additional one in 2013), and another set without such shifts. The shifts are consistent with studies showing protracted falls in investment after a financial crisis, such as the one in Mexico in 1994–1995 (see Reinhart and Tashiro 2013; Chari and Henry 2014). Although no such crisis occurred immediately before 2013–2016, the latter is a period characterized by abnormally slow investment growth in developing economies, including in Latin America (see World Bank 2017), and the downward shift appears to capture this phenomenon. In any event, while the fit of the estimated equations improves, our qualitative results regarding the RER’s effects on investment do not depend on including the intercept shifts.Footnote 12

Table 3 begins with the equations excluding permanent intercept shifts. While all the equations include the RER level decomposed into RERD and RERA, different specifications are used to test the robustness of the estimated effects. Column (3.1) presents the simplest one, which controls only for the industrial production index and public investment level; column (3.2) adds the nominal interest rate and inflation rate, and column (3.3) the monetary aggregate M3; column (3.4), finally, discards the latter variable and adds the manufacturing export level.

Except in the simplest specification in column (3.1), which presents serially correlated residuals, the diagnostic test results are satisfactory. In all the equations, the F bounds test rejects the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship, while the error-correction term shows a large (in absolute terms) negative estimated coefficient. The t bounds test also rejects the null of no long-run relationship in column (3.3), while it fails to do so, but only marginally, in column (3.2).Footnote 13 Overall, the evidence supports the existence of a long-run equation for the determination of the private investment level in Mexico.

The estimated coefficients on the majority of control variables show the expected signs. According to these, private investment responds positively to variations in industrial production and manufacturing exports, and negatively so to variations in the real interest rate—where the latter may come from a higher nominal rate or a lower inflation rate. Adding M3 improves the statistical fit of the estimated equation, but with an unexpected negative coefficient on the new variable which suggests a spurious result. The negative coefficient on government investment, finally, indicates a predominance of substitution effects on private investment, perhaps reflecting the protracted decline of public investment and privatization of assets in Mexico during this period.

Turning to our main results, the estimated coefficients on both RERD and RERA show a positive sign, indicating the presence of qualitatively symmetric effects: while a real peso depreciation tends to increase the investment level, an appreciation does the opposite. Quantitatively, however, the effects are asymmetric: in column (3.2), for example, the estimated coefficient on RER appreciations, at 0.97, is more than twice the estimated coefficient on depreciations. Thus, while an appreciation tends to decrease investment, a depreciation tends to increase it, but to a lesser degree. The results resemble those obtained for the capital accumulation rate in manufacturing, tradables, and the economy as a whole.

4.2.1 Downward shifts

Next, we consider equations that allow for permanent intercept shifts after the peso crisis of 1994–1995 and during the post-2012 global slowdown. To facilitate their interpretation, the estimated shifts are reported as a percentage of the investment levels observed in 1994 and 2012, respectively. Table 4 presents four different specifications: the one in column (4.1) controls for the industrial production index, public investment, and the components of the real interest rate; columns (4.2) and (4.3) add manufacturing exports, and the latter replaces the industrial production index with real GDP; column (4.4), finally, keeps GDP and adds the monetary aggregate M3. Again, the different specifications are intended to explore the robustness of the estimated coefficients on RERD and RERA.

The case for downward shifts in the investment equation is strong. With their inclusion, the statistical fit of the equations improves visibly: both the error-correction coefficient and the F bounds-test statistic increase (compare the equations in columns 4.1 and 4.2 with those in 3.2 and 3.4), and the t test moves to consistently reject the null of no long-run relationship. According to the estimates, and after controlling for a large set of macroeconomic determinants, investment shifted down by about 7% following the currency crisis of 1994–1995, and an additional 2% during the post-2012 global slowdown. For the rest of determinants, the results carry over from those presented in Table 3. In addition, manufacturing exports become statistically significant, suggesting they have a positive effect on investment beyond that of aggregate industrial activity or GDP.

Irrespective of the new intercept shifts, the equations continue to show qualitatively symmetric RER effects: while an appreciation tends to decrease investment, a depreciation tends to increase it. Allowing for intercept shifts, however, does reduce the size of the estimated coefficients on the RER components, particularly so on RERA. This creates some ambiguity about the extent of quantitative asymmetry. In column (4.1), in particular, the Wald test cannot reject the null of equal coefficients on RERD and RERA. Column (4.4) shows the same result, but the equation may be misspecified due to the inclusion of M3. Columns (4.2) and (4.3), finally, do reject the null of equal coefficients. Overall, the evidence continues supporting the hypothesis of quantitatively asymmetric effects of appreciations and depreciations.

4.2.2 Alternative investment series

We now consider whether using the 1993-based investment series changes the estimation results. To do so, we re-estimate the investment equations using the alternative investment (and, for consistency, GDP) series shown as series B in Fig. 2. Table 5 shows the estimation results.Footnote 14 In all the equations, the F bounds test supports the existence of a long-run relationship, while the t test does so in columns (5.1) and (5.4). Also supporting the existence of a long-run relationship, the estimated error-correction coefficient is negative in all the equations. The coefficient is visibly larger in the equations including the industrial production index rather than GDP (as was the case also in Table 4), which suggests the specification with industrial production is to be preferred. Qualitatively, the estimates for the control variables are similar to those reported in previous tables.

Turning to the RER components, the estimated coefficients are positive for both RERD and RERA, which again is consistent with the presence of qualitatively symmetric effects. Also consistent with the previous results, the estimated coefficient on RERA is visibly larger than that on RERD, a difference that is confirmed in statistical terms by the Wald tests. Thus, an appreciation appears to have a larger effect on investment than does a depreciation of similar size. This type of asymmetry is displayed by all equations, except the one in column (5.3), which exceptionallyFootnote 15 shows the opposite pattern. In summary, the use of the alternative investment series does not invalidate the previously reported results; the estimated coefficients on RERD and RERA are in fact larger here than in the corresponding equations in Table 4.

4.2.3 Short versus long run

All the previous results refer to the RER’s final, long-run effects on investment. To conclude, we analyze the path followed by investment before the long-run effects materialize. The paths, which are based on the dynamic multipliers presented in Eq. (4), use the whole structure of coefficients estimated on the lags of the dependent variable and the current and lagged values of the RER component in each equation. While the paths, as must be the case, eventually converge to the long-run coefficients, they may reveal differences between short- and long-run effects.

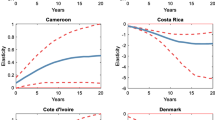

The details of the calculated trajectories change depending on the specific set of controls included in the investment equation, whether intercept shifts are allowed or not, etc. But the different trajectories share some common patterns. First, the effects from both appreciations and depreciations increase over time, gradually moving toward their long-run values. Second, the effects from depreciations fluctuate over time more widely than those from appreciations. And third, but most importantly, while the effects from appreciations are consistently negative in both the short and long run, in the case of depreciations there is a switch in sign, with a positive effect on investment in the long run, but a negative one in the short run. This is consistent with the hypothesis of contractionary effects of depreciations in the short run, but expansionary ones in the long run.Footnote 16

The patterns are illustrated by the time series in Fig. 3. The series show the estimated path followed by investment after a permanent change of one percent—positive (depreciation) or negative (appreciation)—in the RER. In panel (a), the paths were derived from the estimated equations in Tables 3, 4, and 5, columns 3.4, 4.2, and 5.2, which in all cases control for the industrial production index, public investment, the components of the real interest rate, and manufacturing exports. As may be recalled, the equations from Tables 4 and 5 allow for permanent intercept shifts in 1995 and 2013, while the equation from Table 5 uses the alternative series (series B) for public and private investment. The paths in panel (b) were obtained from similar equations but excluding manufacturing exports (columns 3.2, 4.1, and 5.1 in Tables 3, 4, and 5, respectively).

Dynamic multipliers. The series show the path, or dynamic adjustment, of private investment after a permanent one-unit RER depreciation (RERD) or appreciation (RERA), with all the variables measured in natural logs. The paths are based on the dynamic multipliers defined in Eq. (4) in the text and the estimated coefficients in the following equations from Tables 3, 4, and 5: m1, (3.4); m2, (4.2); m3, (5.2) in panel (a); and m4, (3.2); m5, (4.1); m6, (5.1) in panel (b)

As shown in the figure, after an appreciation the effect on investment may increase gradually in absolute terms, but it is always negative. After a depreciation, in contrast, the effect eventually switches sign: it begins negative, but after several quarters it becomes positive. In other words, while appreciations have consistently negative effects on investment, depreciations have contractionary effects in the short run but expansionary ones in the long run.

5 Conclusions

The estimations presented in the paper show that, qualitatively, the RER’s long-run effects on capital accumulation in Mexico are symmetric: while an appreciation decreases the capital accumulation rate in manufacturing, tradables, and the whole economy, a depreciation increases it (with symmetric but opposite and smaller effects in non-tradables); similarly, while an appreciation decreases the aggregate private investment level, a depreciation increases it. Quantitatively, however, the effects appear to be asymmetric, with stronger effects from appreciations than from depreciations; thus, depreciations are beneficial to capital accumulation, but not as much as appreciations are detrimental to it.

The qualitative symmetry implies not only that the appreciation trend of the Mexican peso during much of its post-trade liberalization period slowed the pace of capital accumulation, but that accumulation would have been faster with a depreciated rather than appreciated currency: appreciations act as a barrier while depreciations can be an engine of growth. The quantitative asymmetry, moreover, implies that an alternation of appreciation and depreciation episodes may leave the rate of capital accumulation in manufacturing and tradables, and the overall level of private investment, at persistently lower values. To offset the negative effects of an appreciation episode, the RER must depreciate by more than it initially appreciated.

The estimations in the paper also uncovered the existence of dynamic asymmetries. Indeed, while a depreciation increases the aggregate level of investment in the long run, it decreases it in the short run, in a contractionary effect that may last for several quarters. This dynamic asymmetry contributes to reconciling the apparently contradictory results reached by previous studies that show either contractionary or expansionary RER effects on economic activity in Mexico.

Studying the sources of the RER’s growth asymmetries remains an interesting area of research. One line could follow the growth diagnostics literature (Hausmann et al. 2005b) and test the hypothesis that while depreciations turn the RER into a potential constraint on growth, appreciations in contrast turn it into an actual one. A second line could follow the literature on non-linear exchange-rate pass-through: appreciations may have stronger effects than those of depreciations to the extent that profit margins adjust more easily downwards than upwards. Both lines of research seem promising in the Mexican case.

Notes

Studies using the first definition of the equilibrium RER level include Gala (2008), Rodrik (2008), Di Nino et al. (2011), Berg et al. (2012), Gluzmann et al. (2012), Rapetti et al. (2012), Razmi et al. (2012), and Missio et al. (2015), while among those following the second definition are Béreau et al. (2012), MacDonald and Vieira (2012), Nouira and Sekkat (2012), and Schröder (2013). Several of them, though, use both definitions. Studies that have used the actual RER level instead of an equilibrium one include Hausmann et al. (2005a), Eichengreen (2008), Kappler et al. (2013), Oreiro and Araujo (2013), and De la Torre and Ize (2015). Di Nino et al. (2011) and Rodrik (2008) do so in their robustness exercises.

A review of the general literature on the link between the RER and investment is beyond the scope of this section, but see Blecker (2016) for a recent discussion of investment functions, Baltar et al. (2016) for a look at the empirical literature, and Bahmani-Oskooee and Hajilee (2010) for times-series estimates in a large sample of countries.

To appreciate the sensitivity of such estimates to just one factor—model specification—see the analysis of “thousands of BEERs” by Adler and Grisse (2017).

Note that the choice of base period (or initial value) in the RER decomposition of Eq. (1) does not affect in any way the econometric results to be shown below, except for a change in the estimated value of the equations’ intercept.

In addition, to account for the small number of observations in the accumulation equations, the F bounds test for the existence of a long-run relationship (to be described below) will rely on the small-sample critical values calculated by Narayan (2005).

More specifically, the estimation can combine variables integrated of order zero or one but not higher. The unit-root tests show that this latter condition is met (even without allowing for possible structural breaks in the series) since without exception all variables become stationary after taking their first difference.

Thus, following what has become the common practice (see for example Giles 2013), the t and F tests are applied after simplifying the lag structure of the model. Note also that the number of lags is similar across variables only in the equation’s initial specification, but is allowed to vary in the final specification.

Recalling the discussion in Sect. 2, this type of asymmetry would correspond to a case in which, for example, an appreciation has a negative effect on capital accumulation but a depreciation has no effect: in this case δ2 would be positive but δ1 would not be statistically different from zero.

Note that the estimation methodology makes it possible to obtain statistically significant results for the RER, including a separation between short- and long-run effects, without having to lag the level of the RER with respect to the dependent variable, as previous studies had to do (see for example Blecker 2009 and Ibarra 2010). The better results may be explained by the inclusion of lags in the first-difference segment of the ARDL model.

To interpret the coefficients, recall that a depreciation means an increase in the positively signed RERD series, while an appreciation means an increase in the absolute value of the negatively signed RERA series.

The average growth rate was used as a threshold to ensure that the new series have a relatively similar number of non-zero observations. Otherwise, if a zero threshold had been used (as was done in the RER decomposition of Eq. 1), then the series for the negative production growth rate would have had a disproportionately large number of zeros.

It was not possible to find similar statistically significant shifts in the capital accumulation models of Sect. 4.1, which suggests that a crisis may cause a long-lasting fall in the level but not the rate of capital accumulation.

In this column, the t statistic has a value of − 3.99, while its upper critical bound at 10% of significance is − 4.04.

Since the equations’ statistical fit was better when intercept shifts were included, while the qualitative results were the same with or without them, only the estimates including intercept shifts are reported here, but the results of equations without shifts are available from the author upon request.

The result comes from a very specific combination, namely, (a) using the older 1993-based series, (b) including GDP instead of the industrial production index, and (c) failing to control for manufacturing exports.

Detecting the switch in sign—from negative in the short run to positive in the long run—seems to depend on the use of high frequency (in this case, quarterly) data. Using the dynamic multipliers from the estimates based on the annual data from KLEMS, the path of the capital accumulation rate shows initially small effects that increase gradually over time, in a pattern similar to that of aggregate investment, but with effects in the case of depreciation that are positive from the very first year (results available upon request).

References

Adler K, Grisse C (2017) Thousands of BEERs: take your pick. Rev Int Econ 25:1078–1104

Aguirre A, Calderón C (2006) Real exchange rate misalignments and economic performance. Central Bank of Chile working paper 315, August, revised version

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Hajilee M (2010) On the relation between currency depreciation and domestic investment. J Post Keynesian Econ 32(4):645–660

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Mohammadian A (2016) Asymmetry effects of exchange rate changes in domestic production: evidence from nonlinear ARDL approach. Aus Econ Papers. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8454.12073

Baltar CT, Hiratuka C, Lima GT (2016) Real exchange rate and investment in the Brazilian manufacturing industry. J Econ Stud 43(2):288–308

Béreau S, López-Villavicencio A, Mignon V (2012) Currency misalignment and growth: a new look using nonlinear panel data methods. Appl Econ 44:3503–3511

Berg A, Miao Y (2010) The real exchange rate and growth revisited: the Washington Consensus strikes back? IMF working paper 10/58, March

Berg A, Ostry JD, Zettelmeyer J (2012) What makes growth sustained? J Dev Econ 98:149–166

Blecker RA (2009) External shocks, structural change, and economic growth in Mexico, 1979–2007. World Dev 37:1274–1284

Blecker RA (2016) Wage-led versus profit-led demand regimes: the long and the short of it. Rev Keynesian Econ 4(4):373–390

Caballero E, Lopez J (2012) Gasto público, impuesto sobre la renta e inversión privada en México. Investigación Económica LXXI 280:55–84

Chari A, Henry PB (2014) Two tales of adjustment: East Asian lessons for European growth. NBER working paper 19840, January

De la Torre A, Ize A (2015) Should Latin America save more to grow faster?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 7386, August

Di Nino V, Eichengreen B, Sbracia M (2011) Real exchange rates, trade, and growth: Italy 1861–2011. Bank of Italy Economic History working paper no. 10, October

Eichengreen B (2008) The real exchange rate and economic growth. Commission on growth and development working paper no. 4.The World Bank

Gala P (2008) Real exchange rate levels and economic development: theoretical analysis and econometric evidence. Camb J Econ 32:273–288

Galindo LM, Ros J (2008) Alternatives to inflation targeting in Mexico. Int Rev Appl Econ 22(2):201–214

Garcés D (2008) An empirical analysis of the economic integration between Mexico and the U.S. and its connection with real exchange rate fluctuations (1980–2000). Int Trade J XXII 4:484–513

Giles D (2013) ARDL Models—Part II-Bounds tests. In: Blog post. http://davegiles.blogspot.mx/2013/06/ardl-models-part-ii-bounds-tests.html. Accessed 19 June

Gluzmann PA, Levy-Yeyati E, Sturzenegger F (2012) Exchange rate undervaluation and economic growth: Díaz Alejandro (1965) revisited. Econ Lett 117(3):666–672

Hausmann R, Pritchett L, Rodrik D (2005a) Growth accelerations. J Econ Growth 10:303–329

Hausmann R, Velasco A, Rodrik D (2005b) Growth diagnostics. In: Rodrik D (ed) One economics, many recipes. Globalization, institutions, and economic growth. Princeton University Press, 2007, Princeton, pp 56–84

Ibarra CA (2010) Exporting without growing: investment, real currency appreciation, and export-led growth in Mexico. J Int Trade Econ Dev 19(3):439–464

Ibarra CA (2015) Investment and the real exchange rate’s profitability channel in Mexico. Int Rev Appl Econ 29(5):716–739

Ibarra CA (2016) Tipo de cambio real y crecimiento: una revisión de la literatura, Revista de Economía Mexicana. Anuario UNAM 1:39–86

Kamin SB, Rogers JH (1997) Output and the real exchange rate in developing countries: An application to Mexico. International Finance Discussion Papers 580, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, May

Kappler M, Reisen H, Schularick M, Turkisch E (2013) The macroeconomic effects of large exchange rate appreciations. Open Econ Rev 24:471–494

López J, Sanchez A, Spanos A (2011) Macroeconomic linkages in Mexico. Metroeconomica 62(2):356–385

MacDonald R, Vieira F (2012) A panel data investigation of real exchange rate misalignment and growth. Estudos Económicos 42(3):433–456

Mbaye S (2013) Currency undervaluation and growth: is there a productivity channel? Int Econ 133:8–28

Missio FJ, Jayme FG Jr, Britto G, Oreiro JL (2015) Real exchange rate and economic growth: new empirical evidence. Metroeconomica 66(4):686–714

Narayan PK (2005) The saving and investment nexus for China: evidence from cointegration tests. Appl Econ 37:1979–1990

Nouira R, Sekkat K (2012) Desperately seeking the positive impact of undervaluation on growth. J Macroecon 34(2):537–552

Oreiro JL, Araujo E (2013) Exchange rate misalignment, capital accumulation and income distribution: theory and evidence from the case of Brazil. Panoeconomicus 3(Special issue):381–396

Pesaran MH, Shin Y (1998) An autoregressive distributed-lag approach to cointegration analysis. In: Strom S (ed) Econometrics and economic theory in the 20th century: the Ragnar Frisch centennial symposium. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 371–413

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16:289–326

Rapetti M (2016) The real exchange rate and economic growth: some observations on the possible channels. In: Damill M, Rapetti M, Rozenwurcel G (eds) Macroeconomics and development: Roberto Frenkel and the economics of latin America. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 250–268

Rapetti M, Skott P, Razmi A (2012) The real exchange rate and economic growth: are developing countries different. Int Rev Appl Econ 26(6):735–753

Razin O, Collins SM (1997) Real exchange rate misalignments and growth. NBER working paper 6174, September

Razmi A, Rapetti M, Skott P (2012) The real exchange rate and economic development. Struct Change Econ Dyn 23(2):151–169

Reinhart CM, Tashiro T (2013) Crowding out redefined: the role of reserve accumulation. NBER working paper 19652, November

Rodrik D (2008) The real exchange rate and economic growth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, fall issue, 365–409

Schröder M (2013) Should developing countries undervalue their currencies? J Dev Econ 105:140–151

Shin Y, Yu B, Greenwood-Nimmo M (2014) Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In: Sickles RC, Horrace WC (eds) Festschrift in honor of peter schmidt: econometric methods and applications. Springer, New York, pp 281–314

World Bank (2017) Global economic prospects: weak investment in uncertain times. World Bank Group, Washington, D. C.

Authors’ contributions

CI carried out the entire research and drafted the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank two anonymous referees for their very helpful comments on a previous version of this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed consent

I confirm that I am the sole author of the paper, which contains entirely new and original research and has not been submitted or published elsewhere. If accepted, I will not seek to publish it elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, including electronically.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

I confirm that the research did not involve the participation of humans or animals.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data sources and definitions

1.1.1 Capital accumulation equations

Capital accumulation rate: Percentage growth rate of the net capital stock in manufacturing, tradables as a whole, and non-tradables (see sector definitions below), in referenced prices of 2008. Source Author’s calculations with annual series from the KLEMS database from Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics (INEGI).

Production growth rate: Percentage growth rate of gross production in manufacturing, tradables as a whole, and non-tradables, in constant prices of 2008. Source Same as for capital accumulation rate.

Manufacturing: Sector 31 excluding subsector 324 (petroleum and coal products) in the KLEMS database.

Tradables: Sectors 11 (agriculture, etc.), 21 (mining, excluding subsectors 211, 213, 486: petroleum and gas extraction), and 31 (manufacturing, excluding subsector 324).

Non-tradables: Construction (sector 23) plus whole tertiary sector (services), excluding real estate (subsector 531), education and health services (sectors 61 and 62), and government activities (sector 93).

Real exchange rate (RER) series: See definitions in section on investment equations, below.

1.1.2 Investment equations

Annual inflation rate: Four-quarter change in the consumer price index, in percentage. Source Bank of Mexico (BOM) and INEGI.

Monetary aggregate M3: Ratio of the quarterly average of end-of-month M3 to GDP, both originally in nominal terms, in percentage. Source BOM (for M3) and INEGI (for GDP).

Government investment, series A: Gross fixed capital formation by the public sector, in constant pesos; spliced series: 1988Q1–1993Q1, base 1980; 1993Q2–2016Q3, base 2008; in natural logs times 100. Source INEGI, National Accounts.

Government investment, series B: Spliced series: 1988Q1–1993Q1, base 1980; 1993Q2–2007Q4, base 1993; 2008Q1–2016Q3, base 2008; in natural logs times 100. Source INEGI, National Accounts.

Gross Domestic Product, series A: GDP in constant pesos; spliced series: 1988Q1–1993Q1, base 1980; 1993Q2–2016Q3, base 2008; in natural logs times 100. Source INEGI, National Accounts.

Gross Domestic Product, series B: Spliced series: 1988Q1–1993Q1, base 1980; 1993Q2–2007Q4, base 1993; 2008Q1–2016Q3, base 2008, in natural logs times 100. Source INEGI, National Accounts.

Industrial production index: Quarterly average of seasonally adjusted monthly series; spliced series: 1988Q1–2007Q4: base 1993; 2008Q1–2012Q4: base 2003; 2013Q1–2016Q3: base 2008; in natural logs times 100. Source INEGI.

Manufacturing exports: Exports of manufacturing goods, in US dollars, divided by the US producer price index for industrial commodities less fuel; in natural logs times 100. Source: BOM (for balance of payments data) and US BLS (for price index).

Nominal interest rate: Annual rate on 91-day Treasury bills (CETES); quarterly average of monthly series, in percentage. Source BOM.

Private investment, series A: Gross fixed capital formation by the private sector, in constant pesos; spliced series: 1988Q1–1993Q1, base 1980; 1993Q2–2016Q3, base 2008; in natural logs times 100. Source INEGI, National Accounts.

Private investment, series B: Spliced series: 1988Q1–1993Q1, base 1980; 1993Q2–2007Q4, base 1993; 2008Q1–2016Q3, base 2008; in natural logs times 100. Source INEGI, National Accounts.

RER depreciation component, RERD: Partial sum process corresponding to the sum of positive (depreciation) changes in RER, where RER is the quarterly average (annual average, in the case of the capital accumulation equations) of the real effective exchange rate monthly index (in natural log times 100) calculated by the Bank of Mexico with the consumer price indices of 111 countries. Source Author’s calculations with data from BOM.

RER appreciation component, RERA: Partial sum process corresponding to the sum of negative (appreciation) changes in RER. See RERD for a full description.

1.2 Unit-root tests

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ibarra, C.A. Asymmetric real-exchange-rate effects on capital accumulation: evidence from non-linear ARDL models for Mexico. Lat Am Econ Rev 27, 10 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-018-0057-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-018-0057-x

Keywords

- Real exchange rate

- Capital accumulation

- Investment determinants

- Asymmetric effects

- Non-linear ARDL model

- Mexico