Abstract

Up to now, there have been few monographic analyses of metal ornaments in China. This study presents a case study of the metallurgical archaeology on bracelets from Huili (会理), which may shed light on the issue as production status, technical level, use of raw material and workmanship exchange. Ten bronze bracelets from the Fenjiwan (粪箕湾) site, Huili County and nine ancient slags within 2 km were analyzed by pXRF and MC-ICP-MS methods. The classification of bronze bracelets according to alloy ratio is exactly the same as that of lead isotope. One group used local copper from Huili without adding lead, while the other group added lead material from the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Combined with other relevant data, the results indicate that the technology route of bronze in Southwest China was from Cu-Sn binary alloys to Cu-Sn–Pb ternary alloys, and during the Warring States period (475-221 BC), this region may have certain contacts and exchanges with the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and even the Central Plains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal is very attractive for decorative, representational, instrumental, offensive or ritual purposes in both modern and ancient time. Moreover, metal is relatively easy to process into some small accessories. Among them, the bracelet is one of the most common ornaments on the wrist or ankle, which is circular or oval in shape. Technically, the bracelet was first made of bone or stone [1]. After entering Bronze Age, the ancestors began to cast or make bracelets from metal. Specifically, the ratio between the diameter of the bracelet and the diameter of its metal wire or the width of its metal sheet is usually greater than 5, which is the main feature that can be roughly distinguished from the armband [2]. In addition, bracelets differ in many aspects such as pattern, size, gap, cross-sectional shape, etc.

In China, the earliest known metal bracelets appeared in some ruins of Qijia culture (around 420–3600 BC) and Siba culture (around 3900–3400 BC) in the northwest [3, 4]. After preliminary analysis, it was found that most of them were cast, and the raw materials were red copper or arsenic copper. In the ensuing time, the metal bracelets only spread southward along the crescent-shaped cultural-communication belt, and there was almost no trace in the Central Plains before Han Dynasty [5]. Especially when Southwest China entered bronze age, bronze bracelets began to appear on a large scale and became a prominent feature of this region [6].

Archaeological research in Southwest China in the pre-Han period is currently receiving increasing attention. Some of the results achieved in several relatively large areas have expanded our knowledge of various aspects of southwestern societies during the first millennium BC, as well as the prehistoric communications between this region and areas outside its borders [7,8,9]. Meanwhile, the information provided by metallurgical archaeology has also played a pivotal role. However, most previous research has focused on larger bronzes such as drums and weapons, with little attention paid to smaller objects involving accessories and ornaments [10]. As a portable item, the bracelet is more personalized and more capable of embodying cultural and technical exchange [11].

Therefore, this paper focuses on the technical status of the bronze bracelets in the southwest before the Han Dynasty. At that time, this region was quite closed and less subject to the Central Plains influence. The analysis of a batch of bracelets from the Fenjiwan site in Huili County can help us to better understand the local bronze culture. By revealing alloy characteristics and raw material sources, and combining relevant scientific data, some issues about the production status, technical level, use of raw material, workmanship exchange and even external interactions in Southwestern China can be discussed in more depth.

The archaeological context and samples

The background of Huili

Huili has convenient water and land transportation, and has been a turning point in the trade and commerce between southwest Sichuan, western Yunnan, and South Asia since ancient times. Known as the the ‘lock of Sichuan and Yunnan’, it is across the Jinsha River from Yunnan Province and is the gateway and fortress of the Southern Silk Road. In addition, Huili could also reach eastward to Chongqing by the Jinsha River. Previous archaeological investigations have found stone models for casting copper spears and dagger-axe in Huili, which indicated that local casting activities existed as early as the Warring States Period [12, 13].

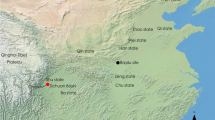

As recorded in Historical Records (史记), ‘Of the dozens of chiefs north of Dian (滇), the most important is Qiongdu (邛都)’. Book of the Later Han (后汉书) depicted that Qiongdu was conquered by Emperor Wu of Han, and the land became an administrative unit of the Han Dynasty. Historians have concluded that the Qiongdu people’s scope of activity was centered on today’s Xichang City (西昌), Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture (凉山彝族自治州), Sichuan Province and Huili County was on the southern border [6].

The archaeological site

The Fenjiwan site is located in Lixi Town, Huili County, within 5 km from the Jinsha River (Fig. 1). Huili County Office for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments revealed 150 densely arranged earthen-pit burials. The walls of these tombs are straight and neat. Generally, the tombs are elongated rectangular in shape, 2 to 4 m long and 0.4 to 0.6 m wide, and up to 2 m deep. Judging from the remaims, the burial style is mainly extended supine, and no funeral implements are found. Pottery occupies a large proportion in funerary objects, accounting for about 90%. Each tomb is usually buried with 1 to 4 pieces of pottery, a few tombs up to 10 pieces. Most of the funerary objects are placed at the head of the tomb, occasionally in the middle of the tomb. Black smoke marks on most potteries indicate that they were practical utensils in life. The yellow color characteristic of the local clay suggests that the ceramic vessels were locally produced. Besides, the number of bronze artifacts is small and most of them are crudely made. The main types of bronze are spears, knives, bracelets and ornaments [12, 14]. According to typology analysis, these tombs should be in the Warring States period, and most of the objects seem to come from local or nearby areas [14, 15].

It is worth noting that gray-green flat-round pebbles were found in almost all tombs. There are only one pebble object in most tombs, while two or three in a few tombs. This funeral custom is very rare in the tombs of the same period in Southwest China. This discovery coincides with the record of Huayangguo Zhi (华阳国志), which is a local chronicle book completed around 350 AD, specialized in ancient China’s southwestern region. It should be that the recorder was also impressed by this unique burial custom and felt the need to take notes [16].

The bronze bracelet and slag samples

The bracelets from the Fenjiwan site are made of plain sheet metal without decoration (Fig. 2). They are relatively uniform in size, leaving a certain gap, and are around 6 cm in diameter. The width and thickness of these bracelets range from 0.1 cm to 0.3 cm, and no more tham 0.5 cm. In addition, the cross sectional shape of all the bracelets is rectangular rather than circular or elliptical. This very popular type in Southwest China makes it difficult to determine whether they are influenced by any particular cultural factors [11, 15].

In addition, for data comparison, Huili County Office for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments provides nine ancient slags (around the 15th century) from Raojiadi (饶家地). It is also located in Lixi Town, Huili County, less than 2 km from the Fenjiwan site and therefore these slags can adequately reflect the information of local deposits and geochemical background.

Analytical methods and results

Component analyses

Since these bronze bracelet are intact and pretty precious, pieces removing or sampling is not encouraged. By the chance of cultural relic restoration, a small part of the surface area of the bracelets was polished until the metal base was exposed. Using a hand-held XRF (Niton XL3t 900He by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Billerica, USA) to obtain the alloy compositions instantly. Slags data were acquired in a similar way. The main filter operates at voltage of 40 kV and current of 100 μA. The alloy mode was selected for bronzes and mining mode for slags. The X-ray beam spot on the sample was about 3 mm in diameter. Elemental data were collected with acquisition time set to 120 s. Final results was obtained by averaging three random analyses.

Lead isotope analyses

Because the analysis of lead isotopes requires very small amounts of samples and does not need to touch the metallic body of the samples, some metal powders are collected for analysis, which are mainly scraped off after polishing to the metal base. Lead isotope analyses were carried out at School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University in Beijing, China and by a MC-ICP-MS (VG AXIOM, Thermo-Elemental Inc., Winsford, England). Firstly, about 2 mg of bronze powders needed to be totally dissolved in mixed solution of 3 ml of HCl and 1 ml of HNO3. Later, the clear solution was leached and diluted with deionized water to 10 ml. The solutions were then measured to detect the lead contents by ICP-AES (PHD, Leeman Labs Inc., California, USA). According to the results representing the lead contents, the solutions were diluted to 1000 ppb. The thallium (T1) standard SRM997 was added in the solutions. Lead isotope analyses were carried out by a MC-ICP-MS (VG AXIOM, Thermo-Elemental Inc., Winsford, England). The spectrometer is a double focusing magnetic sector instrument equipped with an array of 10 variable Faraday collectors. And it has a further fixed Faraday and an electron multiplier detector. Based on repeated analysis of SRM981, the overall analytical 2σ error for all lead isotope ratios was less than 0.106% (Table 1). The results are in good agreement with published values.

Result and discussion

Chemical compositions in bracelets

The pXRF analysis indicates that the bracelets have a concentrated chemical composition with a copper content of about 80% and a tin content of 15%. Based on lead content, they can be divided into two categories (Table 2). Six of them belong to the first category (HL01 ~ 06), with lead content roughly between 2 to 3%. While the lead content of the other category (HL07 ~ 10) do not exceed 0.6%. Some scholars propose that when the lead content is greater than 2%, it should be regarded as an intentional alloy composition [18]. Conversely, lead with low amount indicates that it comes from the original copper ore. According to such criterion, these bracelets have completely different alloy systems. One is Cu-Sn–Pb ternary alloy, and the other is Cu-Sn binary metal.

Moreover, we have also collected all published chemical composition data of bronze bracelets unearthed in the Southwest China before the Han Dynasty (Table 2, Fig. 3). The results shows that the alloy types of these bracelets are complex and the bronze techniques are diverse. Some bracelets even applied special craftsmanship. For instance, tin plating was found in a bracelet from Eryuan (data in the lower right corner of Fig. 3) [20]. Unlike the early copper bracelets in the Northwest China, the bracelets in the southwest are more often added with tin. However, some bracelets from Deqin and Yanyuan are made of copper, which reflect the primitive nature of the material processing [19]. The geographical location of the two places is also relatively close to the north, supporting the idea that metal bracelets were transported from the northwest to the southwest [11]. The emergence and popularity of Cu-Sn alloys in small objects shows that it was known that adding tin could lower the melting point and obtain better properties of the bronze, such as improving the hardness [24]. Furthermore, certain other metallic minerals like lead and arsenic (e.g. two bracelets from Yanyuan) were probably added intentionally or the raw metal ores rich in these elements were deliberately selected to improve the malleability or to enhance the color [23]. However, even with intentional addition of tin and lead, the proportions vary considerably.

In general, metal bracelets do not contain more than 16% tin (the outlier in Fig. 3 is affected by tin plating). After simulating the forging process of bronze with 5–30% tin content, it was noted that copper-tin binary alloys have two ductile forging zones: bronze with tin content less than 18% at 200–300 °C and 20–30% tin at 500–700 °C. The former is more suitable for some degree of thermal processing [25]. From this point of view, the ancestors in Southwest China may have recognized this rule of thumb. Lower machining temperatures are not only easier to achieve and control, but also allow sufficient time for the forging process to further ensure a good structure and performance [26]. Moreover, the tin content of the bracelets unearthed from different places is relatively concentrated and has its own range. The bracelets from Huili, Luliang and Eryuan (only partially) contain relatively similar tin content. And the Huili bracelets with low lead content have almostly the same alloy ratio as the Luliang bracelet and two Yanyuan bracelets, suggesting that potential technical exchanges have taken in these places.

However, the alloy composition of Huili bracelets is more regular and concentrated than that of bracelets from other regions, indicating a stable craft characteristic and good bronze-making skill. It is noteworthy that the difference in lead content is not only found on Huili bracelets. Similar situations arise in Chuxiong Wanjiaba and Jianchuan Haimenkou, where the fluctuations in lead content are more dramatic, which may reflect the experimental stage of adding lead material into bronzes at that time [21, 24]. According to the statistics of the alloy composition analysis of ancient Chinese bronzes by previous scholars, the biggest feature of the alloy technology of bronzes in the Central Plains after Shang Dynasty is that a large amount of lead was added to the bronze, and the lead content is usually above 5%. While most of the bronzes in Southwest China are of little lead, mainly tin bronzes [10]. This shows that the bronze technology route in Southwest China at that time was from Cu–Sn binary alloy to Cu–Sn–Pb ternary alloy.

As for slags, the main chemical element results reveal generally high iron content (Table 3). Regarding to ancient metallurgical industry of China, the iron content of copper slag is relatively high, which is more than 20%, while the iron content of iron slag is generally less than 10% [27]. Accordingly, it can be considered that the slags may be related to copper smelting. The lead content of all slag samples from Raojiadi is below detection limit which demonstrates that the raw metal ores in Huili should not contain high levels of lead. The lead isotopes of these slags reflect the characteristics of the copper deposits. In fact, even if these slags are independent with copper smelting, they can also reflect the geochemical characteristics of the local metallic minerals to a certain extent.

Lead isotopic result

The results of lead isotope analysis of Huili bronze bracelets are given in Table 4. Comparing these LIA data with those of the late Shang bronzes in ancient China, they do not indicate highly radiogenic lead [28]. These lead isotope ratios need to be treated in two parts. One part reflects the characteristics of the lead ore, and the other part reveals the characteristics of the copper ore. However, the isotope data is also divided into two groups without overlap, and is completely consistent with the classification based on chemical composition. The first group (HL01-06) ranges from 17.5 to 17.7 for 206Pb/204Pb, 0.88 to 0.89 for 207Pb/206Pb and 2.16 to 2.19 for 208Pb/206Pb. And the second group (HL07-10) fluctuates from 18.2 to 18.6 for 206Pb/204Pb, 0.84 to 0.86 for 207Pb/206Pb and 2.06 to 2.10 for 208Pb/206Pb.

Most of the lead isotope data collected for lead-bearing minerals in Yunnan are concentrated in the following ranges: 18.0 to 18.5 for 206Pb/204Pb, 0.84 to 0.86 for 207Pb/206Pb, and 2.05 to 2.15 for 208Pb/206Pb (region A in Fig. 4), which indicates that these deposits are very similar in terms of metallogenic history and ore evolution [10]. Based on geochemical provinces theory and the latest summary of lead isotope distribution in China, the first group (HL01-06) is definitely not the lead material produced in the Southwestern China, but from the Yangtze river basin. While the second group (HL07-10) belongs to South China, similar to copper in Yunnan and southern Sichuan [29, 30].

As recorded in Huayangguo Zhi, Qiongdu was famous for producing copper ores in Han Dynasty. It is likely to be developed and utilized earlier than that time. More importantly, there are many copper mines within Huili County, such as the Lala deposit, the Datongkuang deposit, the Xiaoqingshan deposit, and the Tianbaoshan deposit etc. [31,32,33,34]. Thereinto, the Lala deposit produces copper ores with a wide range of lead isotopes, which are usually highly radiogenic. The same situation occurs only occasionally in the other Huili copper deposits. In Fig. 4, we plot only the common lead data for the above four copper deposits and the slags collected near the Fenjiwan site. The ellipse region C represents the extent of lowly radiogenic galena in Southwest China (according to [10, 30]). Since the distribution of lead isotopes in copper is always wider than that in lead, it is easy to understand that region C is covered by region A.

The low-lead group of the bracelets falls into the region A rather than region C, again suggesting that the lead content is not from galena, but from copper ores. Although the data of these bracelets do not exaty match the lead isotope data for the entire southwest China (mainly Yunnan and southern Sichuan), but within the encirclement of the data of slags and ores from Huili (the isotopic ratios of the four bracelets can be derived from a linear combination of the data of slags and ores). Given the particularly large fluctuations in lead isotope of copper ores in this area, it is likely that the data of some small deposits in Huili may be consistent with that of the copper bracelets. Thus, these bracelets should be made of local copper.

On the other hand, region B in Fig. 4 represents the predominated lead isotope ratios in bronzes in central China and middle reaches of the Yangtze River during the late Warring States period [35, 36]. Another group of bracelets completely falls within this range. Besides, we specially collected some LIA data of Yibi coins (蚁鼻钱) of ancient Chu State, as a typical example, for comparison with the high-lead group (Fig. 4). The Yibi coin, which is a unique currency with distinctive Chu style widely used during the Warring States period [37]. Considering that the coinage activities were strictly controlled by the central authority, the Yibi coins should be minted within the territory of Chu with domestic resources. The lead isotope ratios of the bracelets and Chu coins are similar. The three data points of the bracelets almost coincide with one data of the coin. Both the bracelets and the coins belong to region B, which indicates that the lead materials used for the high-lead group of Huili bracelets were probably from Chu at that time.

Other archaeological and historical evidence can also support this judgment. Some traces of the suspected Chu culture have been found on certain types and decorative motifs of bronze wares unearthed in Yunnan [38], especially in some weapons (bronze axe and sword), clothing (hair ornament, hair style and feathered decoration) and musical instruments, etc. [39]. According to Historical Records, King Qingxiang of Chu sent a military force to the southwest in the 3rd century BC. A general of Chu, Zhuang Qiao (庄蹻), reached the Dian Lake as part of the Chu military campaign. When Chu’s homeland was invaded by Qin, Zhuang Qiao decided to stay in Yunnan and adopt indigenous ways to establish the Dian kingdom. In the process, it is likely that some artifacts and culture of Chu were brought into the southwest. However, since the exact date of the Fenjiwan sites could not be determined, the above statement is only a reasonable conjecture. Previous studies of bronzes unearthed in southern Sichuan have shown that there were multiple cultural interactions within Southwest China [40]. Nevertheless, from the perspective of lead isotopes, it can be confirmed that during the Warring States period, the southwest region had certain contacts and exchanges with the Chu state and even the Central Plains region.

Conclusions

In this paper, ten bronze bracelets and nine slags from Huili County have been analyzed. All bracelets contain about 80% copper and 15% tin, suitable for low temperature forging. It shows the stable process characteristics and production levels. According to the level of lead content, these bronze bracelets can be divided into two groups, which coincide with the classification by lead isotope. One group used local copper from Huili without adding lead; while the other group utilized lead material from the middle reaches of the Yangtze River.

Combined with other data of bracelets in Southwest China, it is clear that there are few bracelets directly made of copper, mostly tin bronze, revealing that at that time the ancestors may have recognized the experience of adding tin material to improve alloy properties. But the low lead content shows that the bronze technology route in Southwest China is from Cu-Sn binary alloys to Cu-Sn–Pb ternary alloys. Analysis of the sources of lead suggests that the southwest region had some contacts and exchanges with the the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and even the Central Plains region during the Warring States period. These scientific data provide new evidence for speculation beyond previous style analyses and typology comparisons.

Certainly, more research is needed to verify this conjecture. To further investigate, is is necessary to conduct more scientific analyses of other bronzes in Southwest China.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Gao CM. Research on the name of Chinese dresses and accessories. Shanghai: Shanghai Culture Press; 2001. p. 476–7.

Sun HY. A study of metal jewelries from Han Dynasty to the Southern and Northern Dynasties. Master’s Degree Thesis of Jilin Universit; 2013 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Xu JW. A Scientific Study of Early Metals and Metallurgical Relics Excavated in the Region of Gansu-Qinghai, Northwest China. Master’s Degree Thesis of Beijing University of science and technology; 2009 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Wang L. Scientific Study on Early Copper and Bronze Objects in the Gansu-Qinghai region: with a focus on the Mogou site in Lintan. Doctoral Dissertation of Beijing University of science and technology; 2018 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Tong EZ. Ethnical identification of the megalithic tombs in Southwest Sichuan Province. Kaogu. 1978;02:104–10 (in Chinese).

Sun C, Tang L. Investigation and research on ancient culture in anning River Basin. Beijing: Science Press; 2012 (in Chinese).

Francis A. The archaeology of Dian: trends and tradition. Antiquity. 1999;73:279.

Yao A. Recent developments in the archaeology of Southwestern China. J Archaeol Res. 2010;18(3):203–39.

Zhang HR. Archaeological observation of Yelang civilization. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House; 2014 (in Chinese).

Cui JF, Wu XH. Lead isotope archaeology: a case study of bronzes unearthed in Yunnan, China and Vietnam. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House; 2008 (in Chinese).

Lv HL. A Preliminary study on body ornaments of the southwest barbarians (Xinan Yi), Master’s Degree Thesis of Sichuan University; 2003 (in Chinese).

Tang X. Summary of Huili bronze culture. Sichuan Cultural Relics. 1999;04:51–7 (in Chinese).

Hein AM. Cultural geography and interregional contacts in prehistoric liangshan (southwest china). Dissertations and Theses—Gradworks; 2013.

Tang X. Excavation of Feijiwan Tombs in Huili County, Sichuan Province. Archaeology. 2004;10:36–46 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Hein AM. Interregional contacts and geographic preconditions in the prehistoric liangshan region, southwest china. Quatern Int. 2014;348:194–213.

Liu H. Megalithic graves in Southwest Sichuan and seven tribes of Qiongdu. Wen Wu. 1993;03:85–92 (in Chinese).

Cattin F, et al. Provenance of Early Bronze Age metal artefacts in Western Switzerland using elemental and lead isotopic compositions and their possible relation with copper minerals of the nearby Valais. J Archeol Sci. 2011;38(6):1221–33.

Figueiredo E, Valério P, Araújo MF, Senna-Martinez JC. Micro-EDXRF surface analyses of a bronze spear head: lead content in metal and corrosion layers. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res. 2007;580(1):725–7.

Li XC, Yuan YL, He GH. A Preliminary Analysis of Bronzes and Ironware Unearthed from Ancient Tombs at Yongzhi. J Natl Mus China. 2014;05:148–54 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Li XC, Liu J, Yuan YL, Yang DW. A preliminary study of the Yunnan Eryuan North Mountain pit tombs unearthed bronzes. Jianghan Archaeol. 2015;03:109–15 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Li XC, Min R. Analysis and age of bronze and iron wares from Haimen site in Jianchuan, Yunnan Province in the Third excavation. Archaeol Cult Relics. 2016;03:120–8 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Cui JF, Yang Y, Zhu ZH. Metallurgical analysis and relative study of bronze wares found in Xueguanbao Cemetery, Luliang County, Yunnan Province. South Ethnol Archaeol. 2015;00:115–27 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Cui JF, Wu XH, Zhou ZQ, Jiang ZH, Liu H, Tang L. Metallurgical microscope and chemical analysis of the bronzes from Yanyuan County, Liangshan, Sichuan. South Ethnol Archaeol. 2010;6(00):217–34 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Qiu XK, Wang DD, Huang DR, Wang H. Excavation report of Wanjiaba Ancient Tombs in Chuxiong. Kao Gu Xue Bao. 1983;409:347–82 (in Chinese).

Chadwick R. The effect of composition and constitution on the working and on some physical properties of tin Bronzes. J Inst Metals. 1969;97:331–46.

Qin Y, Li SC, Yan DF, Luo WG. Scientific analysis of hot-forged bronze containers from Eastern Zhou to Qin and Han dynasties unearthed in Hubei and Anhui. Cult Relics. 2015;7:89–96 (in Chinese).

Luo WG, Qing Y, Yuan WQ, Dong YW, Wang CC. Characteristic distinguishment of smelting site by determination results based on some examples. Nonferrous Metals. 2007;04:180–5 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Jin ZY, Liu RL, Rawson J, Pollard AM. Revisiting lead isotope data in shang and western zhou bronzes. Antiquity. 2017;91(360):1574–87.

Zhu BQ. The mapping of geochemical provinces in China based on Pb isotopes. J Geochem Explor. 1995;55:171–81.

Hsu YK, Sabatini BJ. A geochemical characterization of lead ores in China: an isotope database for provenancing archaeological materials. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(4):e0215973.

Sun Y, Shu XL, Xiao YF. Isotopic geochemistry of the Lala copper deposit, Sichuan Province, China and its metallogenetic significance. Geochimica. 2006;5(35):553–9 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Yang ZF. The ore genesis and prospecting direction of Datongkuang copper deposit, Huili County, Sichuan Province. Master’s thesis of Chengdu University of Technology; 2010 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Wen CQ, et al. Geochemical characteristics of Xiaoqingshan copper deposit in Huili County, Sichuan. Acta Geosci Sinica. 1994;14(2):75–83 (in Chinese).

Sun HR, et al. The genetic relationship between Cu-and Zn-dominant mineralization in the Tianbaoshan deposit, Southwest China. Acta Petrol Sinica. 2016;32(11):3407–17 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang J, Chen JL. A preliminary study on the lead isotope ratios of Eastern Zhou bronzes. Cult Relics South China. 2017;02:94–102 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Chen D, Luo WG, Zeng QS, Cui BX. The lead ores circulation in Central China during the Early Western Han Dynasty: a case study with bronze vessels from the Gejiagou site. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0205866.

Jin ZY, Chase WT, Hirao H, Mabuchi H, Yang XZ, and Miwa K. Yellow River Valley and Yangtze River Valley: the question of contact with distant bronze cultures, in Essays from the international conference on the Shang Culture (ed. Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences), 425–3, Great Encyclopedia Press, Beijing, 1993 (in Chinese).

Rawson J. ‘Forward’ The Chinese Bronzes of Yunnan. (London: Sidgwick and Jackson Limited; Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House; 1983, pp. 7–9.

Chiou-Peng T. Horsemen in the Dian culture of Yunnan. In: Linduff KM, Sun Y, editors. Gender and Chinese archaeology. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press; 2004. p. 289–313.

Liu ZF, Yang YD, Luo WG. A lead isotope Study of the Han dynasty bronze artifacts from Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture Museum, Sichuan Province, Southwest China. Curr Anal Chem. 2016;12:553.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved the quality of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is Supported by the Ancient Shu Civilization Protection and Inheritance Project, the Chengdu Archaeological Institute (201812-187), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS, the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. 2019-Y954026XX2), the youth fund of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education, P. R. China (19C14430008), National Social Science Fund of China (No. 17XKG003), China Scholarship Council (CSC NO. 201904910738), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41471167).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DC and WL performed the data analysis and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. JD analyzed the lead isotope data. YY, and XT provided the archaeological context. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Yang, Y., Du, J. et al. Alloy ratio and raw material sourcing of Warring States Period bronze bracelets in Huili County, Southwest China by pXRF and MC-ICP-MS. Herit Sci 8, 69 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00413-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-020-00413-z