Abstract

Background

Eucalyptus species can be alternative plantation species to Pinus radiata D.Don (radiata pine) for New Zealand. One promising high value use for eucalypts is laminated veneer lumber (LVL) due to their fast growth and high stiffness. This study investigated the suitability of Eucalyptus globoidea Blakely for veneer and LVL production.

Methods

Twenty-six logs were recovered from nine 30-year-old E. globoidea trees. Growth-strain was measured using the CIRAD method for each log before they were peeled into veneers. Veneer recovery, veneer splitting and wood properties were evaluated and correlated with growth-strain. Laminated veneer lumber (LVL) panels were made from eucalypt veneers only or mixed with radiata pine veneers to investigate the bonding performance of E. globoidea.

Results

Veneers with no, or limited, defects can be obtained from E. globoidea. Veneer recovery (54.5%) correlated with growth-strain and was highly variable between logs ranging from 23.6% to 74.5%. Average splitting length in a veneer sheet was 3.01 m. There was a moderate positive association between splitting length and growth-strain (r = 0.73), but no significant association with wood stiffness (r = 0.27). Bond quality of LVL panels prepared using E. globoidea veneer and a phenol formaldehyde adhesive did not satisfy AS/NZ 2098.2.

Conclusion

Usable veneers for structural products could be obtained from E. globoidea at yields of up to 74.5%, but variation in the existing resource (which has not been genetically improved) was large. In particular, growth-strain reduced veneer recovery by splitting, largely independent of stiffness. The considerable variation in growth-strain and stiffness indicated a possibility for genetic improvement. Furthermore, a technical solution to improve bonding of E. globoidea veneers needs to be developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eucalyptus species are hardwoods and make up 26% of the global forest plantation estate (FSC 2012). Plantation eucalypt species can grow fast, reaching up to 30 cm at the base in 8 years (de Carvalho et al. 2004), and are currently mostly grown for chip wood to supply the pulp & paper industry. However, eucalypt timber is generally of higher stiffness than that of most softwood species, the main plantation resource for solid-wood processing. High stiffness is beneficial for products used in structural applications, such as in laminated veneer lumber (LVL) (Bal and Bektaş 2012). Plantation-grown eucalypts have been investigated previously for use in LVL. In general, good veneer qualities (Acevedo et al. 2012), satisfactory mechanical properties (de Carvalho et al. 2004; Palma and Ballarin 2011) and no major gluing problems were reported for eucalypt resources with air-dry densities less than 650 kg/m3 (Hague 2013, Ozarska 1999).

A major obstacle to using eucalypts for veneers and LVL is the high level of growth-stresses present in the logs. These growth-stresses are generated by the newly formed wood cells. The exact molecular mechanism by which the cell walls generate such large stresses is unknown (Alméras and Clair 2016; Okuyama et al. 1994; Toba et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2005). However, the newly formed cells tend to contract longitudinally and expand transversely during cell wall maturation. As a consequence, the centre of the stem is under axial compression while the outside is under axial tension (Kubler 1987). These growth-stresses are released when cutting into the stem i.e. during felling, sawing or veneer peeling. The release of growth-stresses can lead to severe end-splitting following a crosscut, board distortion during sawing and breakage of veneers in the peeling process (Archer 1987; Jacobs 1945; Yang and Waugh 2001). These defects are more prominent in smaller diameter logs, i.e. a plantation resource. Splitting of veneers caused by growth-stress lowers veneer quality and reduces yield. For example, only 20% usable veneers were recovered from E. grandis W.Hill due to severe end-splitting (Margadant 1981). To date, no technological solution to reduce the effects of growth-stresses has been implemented successfully.

Unlike the global plantation estate, eucalypts and other hardwood species account for only 2% of the New Zealand plantation area, which is dominated by Pinus radiata D.Don (radiata pine) (90%) (MPI 2016). Interest in establishing commercial eucalypt plantations dates back to the late nineteenth century with the introduction and testing of many eucalypt species around that time (Barr 1996; McWhannell 1960; Miller et al. 1992; Miller et al. 2000; Shelbourne et al. 2002; Simmonds 1927). Their work identified various Eucalyptus species that suit New Zealand conditions. However, today E. nitens (H.Deane & Maiden) Maiden is the only Eucalyptus species that is currently grown commercially on a large scale. There are more than 10,000 ha E. nitens in Southland and Otago (in the southern South Island), but the species suffers from fungal and insect attack in the warmer North Island (McKenzie et al. 2003; Miller et al. 1992). Some small commercial plantings of E. fastigata H. Deane & Maiden and a small amount of E. regnans F.Muell. can also be found (Miller et al. 2000). The development of these three species is supported by breeding programmes: E. nitens (Telfer et al. 2015); E. fastigata (Kennedy et al. 2011); and E. regnans (Suontama et al. 2015). Eucalyptus nitens is currently grown for chip wood export for the pulp industry. Generally, it is possible to manufacture quality LVL from 15-year old E. nitens, which was reported to have an average MoE of 14.3 GPa and achieving F17 grade according to AS/NZS 2269 (2012) (Gaunt et al. 2003). This compares favourably to the majority of radiata pine LVL products manufactured in New Zealand, the MoE of which range between 8 and 13 GPa, and which relies on using the better part of the radiata pine resource. Apart from growth-stress, E. nitens has been reported to suffer from collapse and internal checking during drying (Lausberg et al. 1995; McKenzie et al. 2003; McKinley et al. 2002).

None of the currently commercially grown eucalypts produce naturally ground-durable and coloured timber even though the value of such a resource was identified many years ago by early eucalypt enthusiasts (McWhannell 1960; Simmonds 1927). Interest in growing these eucalypt species to produce high-value speciality timbers continued in the forestry sector but smaller growers favoured different species so no critical mass has been achieved to date. Furthermore, a successful plantation industry needs to be supported by a breeding programme (Miller et al. 2000). Tree-breeding programmes require a wide genetic basis and are costly, highlighting the need to focus resources on a few species.

Three major research initiatives involving durable eucalypts in New Zealand have been initiated in the last two decades. The Forest Research Institute (Scion) and the New Zealand Forestry Association undertook a series of trials on eucalypts with stringy bark. However, these were either discontinued due to a lack of funding or have a narrow genetic base (van Ballekom and Millen 2017). The New Zealand Dryland Forests Initiative (NZDFI) has been working since 2008 to establish a eucalypt forest industry producing naturally durable timber based on a large scale-breeding programme of three species E. bosistoana F.Muell., E. quadrangulata H. Deane & Maiden and E. globoidea (Millen 2009). This breeding programme took a range of wood-quality traits into account (including low growth-stress). While primarily chosen for the natural durability of their heartwood, these species also produce wood of high stiffness - up to 20 GPa (Bootle 2005). Demand for engineered timber products with exceptional stiffness has been generated by the emergence of high-rise timber buildings (Van de Kuilen et al. 2011). These species also have naturally durable heartwood so it may be possible to produce preservative-free durable LVL (McKenzie 1993; Page and Singh 2014). Some information on the wood properties of E. bosistoana, E. quadrangulata and E. globoidea is available from old-growth resources in Australia (Bootle 2005), but only young plantation-grown E. globoidea has been studied previously in New Zealand. Eucalyptus globoidea has been reported to be well suited for plantation forestry with good tree health, growth and adaptability combined with favourable timber properties of good stiffness and natural durability (Barr 1996; Haslett 1990; Millner 2006). Additionally, it is easy to dry and has relatively low growth-stress levels (Jones et al. 2010; Poynton 1979). No information on peeling parameters, veneer drying or bonding has been reported for this species, however.

Eucalyptus globoidea was selected for the present study to evaluate its suitability for veneer and LVL production considering the fact that sufficiently large trees could be sourced from a farm-forestry operation. To the best of our knowledge, no sufficiently large E. bosistoana or E. quadrangulata trees are available in New Zealand for processing research. Growth-strain of logs was measured and then peeled into veneers. Green veneer recovery and peeling quality were evaluated and relationships between these attributes and both growth-strain and dynamic modulus of elasticity (MoE) were investigated. Physical properties including density, shrinkage and moisture content of dried veneer were also monitored. E. globoidea veneers were used to manufacture pure eucalypts LVL and mixed LVL with radiata pine veneers to investigate the bonding performances.

Methods

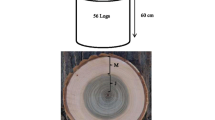

Nine E. globoidea trees with straight form were randomly chosen and felled from a 30-year-old stand in the lower North Island (latitude 40° 11′ 12" S, longitude 175° 20' 35" E, elevation 60 m) in May 2016. The stems were manually debarked immediately after felling. From these stems, 26 suitable logs for peeling of 2.7 m length were recovered. The small end (SED) and large end diameters (LED) were measured for each log in order to calculate log volume.

Growth-strain measurement

For each log, the amount of growth-strain was determined with the CIRAD method (Gerard et al. 1995). The growth-strain is variable on the surface of a stem (Gerard et al. 1995). Therefore, growth-strain was measured on four positions at ~1.35 m spaced by ~900 around the circumference of each 2.7 m log. The four assessments for each log were averaged. Measuring points were chosen in straight-grained areas in close proximity to the above described positions in order to avoid knots. It was calculated from the measured change in distance between the pins according to Eq. (1).

α = −φ δ (1).

where α is the strain in microstrain; δ is the measured displacement in μm and φ is a constant dependent on tree species. The published value for eucalypt of φ = 11.6 was used (Fournier et al. 1994).

Rotary peeling and veneer evaluation

The trees were transported to Nelson Pine Industries Ltd. (NPI), Richmond, NZ for processing. All logs were heated at 85 °C for 24 h in a water bath before peeling 8 days after felling. 23 of the 26 logs were peeled to a core diameter of 82 mm using a spindled lathe (Raute, Finland) with three-stage chucks. The remaining three logs fell off the lathe with a larger peeler core (133 to 162 mm in diameter) due to severe end-splitting. Veneers with a thickness of 3.74 mm were produced from all 26 logs. During the peeling process, the recovery and volumes of different types of waste (core, round-up, spur, clipper defects) were recorded for each log. After clipping, 296 veneer sheets were obtained. Recovery was defined as the ratio of the obtained veneer volume to log volume. Veneer volume was calculated based on the number of sheets and the thickness and dimensions of sheets. For comparison, NPI provided the average recovery data of more than 46,000 radiata pine logs (2.7 m long) collected previously from the production line. The radiata pine logs used in this study were sourced from plantations and woodlots in Nelson and Marlborough. Veneer splitting was the major defect with few knots or other defects found so the aggregate defect rule according to AS/NZS 2269.0 (2012) was not applied. The green veneer sheets were visually graded to four classes (face, core, composer, waste) according to their splitting severity by the technical manager in NPI. Only face and core grades were considered to be usable veneer.

From the dryer line with the Metriguard 2655 DFX instrument (USA), ultrasonic propagation velocity and width data were made available for each veneer sheet. The individual veneer sheets could be tracked back to the individual logs. With the clipping width known, the width data were used to calculate the tangential shrinkage. The number of splits in each veneer was counted from the Novascan grader (Grenzebach, Germany) images. ImageJ software (National Institute of Health, USA) was used to analyse the splitting lengths.

After drying, a strip approximately 200-300 mm wide was taken from a sheet near the start and the end of each veneer mat. The dimension and weight of this strip were measured to obtain dried density. These test pieces were then dried further in an oven at 103 °C until constant weight to obtain the moisture content.

The dynamic modulus of elasticity (MoE) was calculated from ultrasound acoustic propagation velocity and wood density data according to Eq. (2).

E= V2ρ (2).

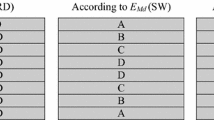

Where V is the ultrasonic velocity, E is the dynamic MoE and ρ is the density. Static MoE for the population of sheets was estimated by multiplying the dynamic MoE with a factor of 0.868. The factor was empirically determined by laminating test panels of Eucalyptus globodiea veneers with known dynamic MoE and conducting static 4-point bending tests in the edgewise direction.

Bonding quality of eucalyptus veneer

Ten laboratory-scale 10-ply LVL panels were manufactured. Six panels were made of eucalypt veneer only, choosing veneer sheets of defined MoE grades based on their dynamic MoE values. One panel each was made from 12, 14, or 17.5 GPa sheets and three panels were made from 16 GPa sheets. Each LVL panel contained veneer from one or two logs only. Another four panels were made of five radiata pine and five eucalypt veneer plies. A range of eucalypt grades were used in these panels. The first (14 GPa), third (17 GPa), sixth (14 GPa), eighth (12 GPa) and tenth layers (12 GPa) were eucalypt veneers and the rest were radiata pine. Two panels were made from each of G2 and G4 radiata-pine grades. A typical phenolic formaldehyde adhesive manufactured by Aica NZ Limited was used at a rate of 180 g/m2. Panels were hot-pressed at 160 °C with a pressure of 1.2 MPa.

The quality of the glueline was assessed according to AS/NZS 2098.2 (2012), which measures the percentage of area covered by wood after two veneers have been split apart. According to AS/NZS 2269.0 (2012), bonding between the plies in LVL shall be a Type A bond. This specification requires a phenolic adhesive complying with AS/NZS 2754.1 (2016) and also a bond quality of any single glueline not less than 2 and an average of all gluelines not less than 5 when tested according to AS/NZS 2098.2 (2012). Both a steam and a vacuum pressure method were used to assess glueline quality (AS/NZS 2098.2 2012).

Results and discussion

Rotary peeling and veneer recovery

For the 26 logs of 2.7 m tested, the small end diameter averaged 34.4 cm with a standard deviation of 4.3 cm while the large end diameter averaged 38.9 cm with a standard deviation of 6.3 cm. The average diameter of the E. globoidea logs (36.3 cm) was comparable to the radiata pine logs (34.9 cm) used in the plant for LVL production. In a preliminary test, an additional E. globoidea log was peeled cold. This was unsuccessful and, therefore, preheating to soften the wood was deemed necessary.

The average veneer recovery for the 26 E. globoidea logs (54.5%) was lower than for radiata pine logs (69.8%) but the best E. globoidea log had a recovery of 74.5% (Tables 1 and 2). This result was mainly due to a 6% higher loss in the peeler core caused by severe splits in the supplied E. globoidea logs and an 11.7% greater clipper loss caused by end-splitting of the veneers compared with the radiata pine logs. However, the amount of round-up waste was lower for the eucalypt logs than the radiata pine logs, which indicated a better log form for E. globoidea. Veneer recovery from individual logs was highly variable ranging from 23.6% to 74.5% (Table 2). A previous peeling study with E. nitens reported an overall recovery of 59% (McKenzie et al. 2003). However, part-sheets were included in that study while only full sheets were calculated in the present study.

A spindled lathe was used to peel the logs in the current study but spindleless lathes are extensively used in China. They are suitable for rotary peeling smaller diameter logs from young and fast-grown hardwood plantations (McGavin 2016). Spindleless lathes achieve higher yields because they can peel logs to smaller peeler core diameters compared to spindled lathes currently used for radiata pine. Moreover, spindleless lathes can control splits by pressing the splits together during peeling. Therefore, using this type of lathe may generate higher recovery and quality of veneer sheets.

Growth-strain and veneer splitting

High quality veneers can be obtained from E. globoidea although splitting significantly degraded the visual appearance of many veneers (55% of the veneers had splitting lengths longer than 2 m). Veneers with no and severe splitting are shown in Fig. 1.

The average recovery of useable veneer (face and core grades) from E. globoidea was 33.4%. Severe splitting caused by growth-stress contributed to the low recovery. The average growth-strain was 839.4 με measured by the CIRAD method. The log with the lowest growth-strain had approximately half the growth-strain compared with that with the highest. Usable veneer recovery was negatively associated with growth-strain (Fig. 2). The average useable veneer recovery for the logs in the bottom quartile (growth-strain >965.7 με) was 5.8%, while that for the top quartile (growth-strain <701.8 με) was 57.2%.

The mean splitting length per veneer for individual logs ranged from 0.15 m to 8.66 m. For a veneer 2.65 m in length and 1.26 m in width, the average total splitting length was 3.01 m. This suggested splitting was limiting veneer quality.

The splitting length was measured after the veneers were dried. Drying was likely to exaggerate the splitting lengths but was assumed to affect all veneers equally in this study. In addition, rough handling and peeling settings can also contribute to the splitting of veneers. It was assumed that all veneers were equally affected in these ways and the differences among them were mainly caused by growth-stress.

A positive correlation (r = 0.73) was observed between splitting lengths in veneers and growth-strain of corresponding logs (Fig. 3). In this study, average splitting length was low when growth-strain was less than ~800 με (CIRAD). Longitudinal growth-strain was reported to be positively related to end-splitting of E. nitens and E. globulus logs (Valencia et al. 2011; Yang and Pongracic 2004). The number of splits in a veneer sheet is another measure to evaluate veneer spitting. A strong linear relationship (r = 0.91) was obtained between splitting length and split numbers (Fig. 3). Considering that the measurement of the number of splits is less time consuming than quantifying splitting length, it might be a better option for future studies.

This result indicated that higher veneer recovery and quality would be possible if growth-stresses were reduced. Methods to control the growth-stress and minimise splitting are difficult to perform, have not been successful in industrial applications and incur ongoing costs (Archer 1987; Malan 1995; Yang and Waugh 2001). Growth-stresses are heritable and selecting trees with low growth-stress in a breeding programme can potentially solve this problem for a future resource such as E. globoidea (Davies et al. 2017; Malan 1995). For existing eucalypt plantations grown for the lower-value wood chips, such as E. nitens, segregation would be an option. However, current methods of measuring growth-stress are time consuming and cumbersome, making this approach impractical (Yang and Waugh 2001). Rapid and non-destructive segregation methods need to be developed. For example, Yang et al. (2006) measured growth-strain of 10-year-old E. globulus and found correlations with cellulose crystallite width measured using a SilviScan-2 instrument.

The relationship between splitting length and radial position for five logs is shown in Fig. 4. The splitting length of the veneer sheets tended to increase towards the centre of the stem (position 0). The decreasing circumference with decreasing radius results in shorter tangential distances between the radial end-splits of the logs. Furthermore, the increasing curvature with decreasing radius can facilitate splitting. However, the variation between the stems was much bigger than the radial effect, with the veneer splitting independent of radius for the worst and the best logs.

It is worth noting that the log preheating and peeling settings in this study were optimised for radiata pine. Acevedo et al. (2012) reported that better quality veneers were obtained from E. nitens by adjusting nose bar pressure and peeling knife angle.

Physical and mechanical properties of veneer

After drying, the average dry density was 668 kg/m3 and the average moisture content was 7.3% (Table 3). No excessively high or low moisture contents were found, which indicated homogeneous drying of the E. globoidea veneers.

The average shrinkage of the E. globoidea veneers was 9.9% tangentially and varied between 8.5 and 11.3%. Most veneers were heartwood as the sapwood in E. globoidea is very narrow. For comparison, typical tangential shrinkage values for radiata pine veneers are 6.4% for sapwood and 4.4% for heartwood. Higher shrinkage will result in greater volume loss. It should be noted that, within species, heartwood typically displays lower shrinkage than sapwood.

The average dynamic MoE calculated for the E. globoidea veneer sheets from Metriguard acoustic velocity and interpolated lab density was 14.67 GPa ranging from 9.59 to 20.26 GPa (Fig. 5). The equivalent static MoE was estimated to be 12.73 GPa based on the empirical conversion equation. Common LVL products manufactured from radiata pine range from 8 to 11 GPa. Jones et al. (2010) investigated 25-year-old E. globoidea for high-quality solid wood production. Boards from the butt logs were reported to have an average density of 655 kg/m3, dynamic MoE of 13 GPa and static MoE of 12 GPa. According to Haslett (1990), the timber of E. globoidea (over 25 years old) in New Zealand has an MoE of 14.6 GPa at a moisture content of 12%.

High stiffness wood tended to have higher growth-strain (Fig. 6). This is an unfavourable association as stiff wood with low growth-strain is desirable. However, the association between MoE and growth-strain was moderate (r = 0.65) implying the existence of stiff logs which are low in growth-strain. Several logs produced veneers with MoEs above 15 GPa and growth-strain levels below 800 με. More importantly no association (r = 0.27) was found between veneer splitting and stiffness, which demonstrated that peeling quality needs to be improved through reducing growth-stress rather than through MoE. The stiffest logs yielded veneers with an MoE of up to 19.5 GPa, but these did not necessarily have a severe splitting problem. Therefore, it seems possible to obtain a stiff eucalypt resource that yields high-quality veneers.

A weak positive association (R2 = 0.26) between CIRAD longitudinal displacement and MoE has been found previously in E. globulus (Yang et al. 2006). With the increase of longitudinal displacement, microfibril angle tended to decline while density increased. Similar associations between growth-strain and wood properties have been reported for wood from Populus deltoides Bartr (Fang et al. 2008). However, no statistically significant associations were found between growth-stain and dynamic MoE or density for E. nitens (Chauhan and Walker 2004).

The average distribution of MoEs for the veneers obtained from the nine trees assessed is shown in Fig. 7. As for veneer splitting, the variance in MoE among trees was large with the average stiffness ranging from 12.1 GPa to 18.0 GPa. Analysis of variance found significant differences (P < 0.001) in MoE values of veneers from different trees.

It has to be noted that the tested E. globoidea was genetically unimproved material of unknown provenance. Wood properties like growth-stress and MoE are under genetic control (Davies et al. 2017). Murphy et al. (2005) reported a heritability of 0.3 to 0.5 for growth-strain in Eucalyptus dunnii Maiden and indicated tree breeding can be an effective method to reduce growth-stress. Considerable variation among trees was observed, indicating a potential for genetic improvement. The relatively high acoustic velocity of eucalypts in the corewood could allow peeling veneers to a smaller peeler core with spindleless lathes, improving yields and allowing the use of a small diameter younger resource.

Bonding quality

The bond test revealed poor bonding of the plies. None of the panels made with E. globoidea alone passed the specifications for structural LVL (Table 4). Density seemed to exaggerate the bonding difficulty for the 100% E. globoidea LVL. Eucalyptus globoidea panels with densities higher than 800 kg/m3 had average bonding qualities lower than 3. Alternating E. globoidea and P. radiata veneers improved bond quality, and all samples passed the steam test, but only one sample passed the immersion test. The glueline between radiata pine plies was excellent (Table 5).

Eucalypts have a higher density and extractive content than radiata pine, and both these factors can make gluing difficult. In Australia, difficulty in bonding veneers from dense eucalypts (air-dry density above 700 kg/cm3) are known and some special adhesive formulations have been developed for these species (Carrick and Mathieu 2005; Ozarska 1999). It is commonly stated that low and medium density (below 650 kg/cm3) eucalypts glue well but young E. nitens was found to have bonding issues however (de Carvalho et al. 2004, Farrell et al. 2011, Hague 2013). Plywood products made from various Eucalyptus species have been reported in China, Malaysia, Uruguay and Brazil indicating that satisfactory bonding can be achieved for many Eucalyptus species (de Carvalho et al. 2004; Hague 2013; Turnbull 2007; Yu et al. 2006). Therefore, it seems probable that a technical solution for gluing E. globoidea can be found.

Conclusions

-

1)

Veneer recovery ranged from 23.6% to 74.5% among 26 E. globoidea logs. Larger peeler core and higher clipper losses occurred compared to radiata pine.

-

2)

High-quality veneers could be obtained from E. globoidea. Low growth-strain logs produced more usable veneers. Splitting degraded veneer quality.

-

3)

Splitting length in veneers was correlated to growth-strain of the corresponding logs. Split number was strongly associated with splitting length and can be used to evaluate veneer splitting severity. Veneers from inner wood tended to a have longer splitting lengths; however differences among logs were more pronounced.

-

4)

Moisture contents of dried veneers indicated good drying of E. globoidea. The average tangential shrinkage was 9.9% and the volume loss was higher than for radiata pine. Larger shrinkage is a common feature of high-density timbers.

-

5)

The average dynamic MoE was 14.67 GPa ranging from 9.59 to 20.26 GPa. No association was found between splitting length and stiffness. It should be possible to find stiff logs, however, which would yield satisfactory veneers. The considerable variation in stiffness observed here indicated a potential for genetic improvement.

-

6)

The lack of association between stiffness and splitting length suggested that quick acoustic measurements for segregating eucalypt logs suitable peeling are unlikely to be successful.

-

7)

Bond performance of E. globoidea LVL was poor and did not meet the New Zealand standard. Alternating E. globoidea and P. radiata veneers improved bond quality, but bonding of E. globoidea veneers still needs to be addressed.

References

Acevedo, A, Bustos, C, Lasserre, JP, Gacitua, W. (2012). Nose bar pressure effect in the lathe check morphology to Eucalyptus nitens veneers. Maderas. Ciencia y tecnologia, 14(3), 289–301.

Alméras, T, & Clair, B. (2016). Critical review on the mechanisms of maturation stress generation in trees. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 13(122), 20160550.

Archer, RR (1987). Growth stresses and strains in trees. Berlin: Springer-Verlag Gmbh.

AS/NZS 2098.2 (2012). Methods of test for veneer and plywood. Method 2: Bond quality of plywood (chisel test). Wellington: Standards Australia/ Standards New Zealand.

AS/NZS 2269.0 (2012). Plywood-structural. Part 0: Specifications. Wellington: Standards Australia/ Standards New Zealand.

AS/NZS 2754.1 (2016). Adhesives for timber and timber products. Part 1: Adhesives for manufacture of plywood and laminated veneer lumber (LVL). Wellington: Standards Australia/ Standards New Zealand.

Bal, BC, & Bektaş, I. (2012). The effects of some factors on the impact bending strength of laminated veneer lumber. BioResources, 7(4), 5855–5863.

Barr, N. (1996). Growing eucalypt trees for milling on New Zealand farms. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Farm Forestry Association.

Bootle, KR (2005). Wood in Australia. Types, properties and uses, (2nd ed., ). Sydney: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Carrick, J, & Mathieu, K (2005). Durability of laminated veneer lumber made from Blackbutt. In Proceedings of the 10DBMC international conference on durability of building materials and components, France.

Chauhan, SS, & Walker, J. (2004). Relationships between longitudinal growth strain and some wood properties in Eucalyptus nitens. Australian Forestry, 67(4), 254–260.

Davies, NT, Apiolaza, LA, Sharma, M. (2017). Heritability of growth strain in Eucalyptus bosistoana: A Bayesian approach with left-censored data. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 47, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-017-0086-2.

De Carvalho, AM, Lahr, FAR, Bortoletto Jr, G. (2004). Use of Brazilian eucalyptus to produce LVL panels. Forest Products Journal, 54(11), 61.

Fang, C-H, Guibal, D, Clair, B, Gril, J, Liu, Y-M, Liu, S-Q. (2008). Relationships between growth stress and wood properties in poplar I-69 (Populus Deltoides Bartr. Cv. “Lux” ex I-69/55). Annals of Forest Science, 65(3), 307.

Farrell, R, Blum, S, Williams, D, Blackburn, D (2011). The potential to recover higher value veneer products from fibre managed plantation eucalypts and broaden market opportunities for this resource: Part A. (project no: PNB139-0809). Melbourne: Forest & Wood Products Australia.

Fournier, M, Chanson, B, Thibaut, B, Guitard, D. (1994). Measurements of residual growth strains at the stem surface. Observations on different species. Annales des Sciences Forestières, 51(3), 249–266.

FSC (2012). Strategic review on the future of forest plantations. Helsinki, Finland: Forest Stewardship Council.

Gaunt, D, Penellum, B, McKenzie, HM. (2003). Eucalyptus nitens laminated veneer lumber structural properties. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 33(1), 114–125.

Gerard, J, Bailleres, H, Fournier, M, Thibaut, B. (1995). Wood quality in plantation eucalyptus - a study of variation in three reference properties. Bois et Forêts des Tropiques, 245, 101–110.

Hague, J. R. B. (2013). Utilisation of plantation eucalypts in engineered wood products. Melbourne, Australia.

Haslett, A. N. (1990). Properties and utilisation of exotic speciality timbers grown in New Zealand. Part VI: Eastern blue gums and stringy barks. Eucalyptus botryoides Sm. Eucalyptus saligna Sm. Eucalyptus globoidea Blakey. Eucalyptus muellerana Howitt. Eucalyptus pilularis Sm. (FRI Bulletin 119). Rotorua: New Zealand Forest Research Institute.

Jacobs, MR (1945). The growth stresses of woody stems. Canberra: Commonwealth Forestry Bureau.

Jones, TG, McConnochie, RM, Shelbourne, T, Low, CB. (2010). Sawing and grade recovery of 25-year-old Eucalyptus fastigata, E. globoidea, E. muelleriana and E. pilularis. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 40, 19–31.

Kennedy, S, Dungey, H, Yanchuk, A, Low, C. (2011). Eucalyptus fastigata: Its current status in New Zealand and breeding objectives for the future. Silvae Genetica, 60(6), 259–266.

Kubler, H. (1987). Growth stresses in trees and related wood properties. Forestry abstracts, 48(3), 131–189.

Lausberg, M, Gilchrist, K, Skipwith, J. (1995). Wood properties of Eucalyptus nitens grown in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 25(2), 147–163.

Malan, FS. (1995). Eucalyptus improvement for lumber production. Seminario Internacional de Utilização da Madeira de Eucalipto, 15, 1–19.

Margadant, R. (1981). Why not peel locally grown eucalyptus. Wood Southern Africa, 6(10), 8–22.

McGavin, RL (2016). Analysis of small-log processing to achieve structural veneer from juvenile hardwood plantations. Melbourne: The University of Melbourne.

McKenzie, H. (1993). Growing durable hardwoods - a research strategy. New Zealand Journal of Forestry, 38(3), 25–27.

McKenzie, H, Turner, J, Shelbourne, C. (2003). Processing young plantation-grown Eucalyptus nitens for solid-wood products. 1: Individual-tree variation in quality and recovery of appearance-grade lumber and veneer. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 33(1), 62–78.

McKinley, R, Shelbourne, C, Low, C, Penellum, B, Kimberley, M. (2002). Wood properties of young Eucalyptus nitens, E. globulus, and E. maidenii in northland, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 32(3), 334–356.

McWhannell, F. B. (1960). Eucalypts for New Zealand farms, parks and gardens. Hamilton, N.Z: Paul's Book Arcade.

Millen, P (2009). NZ Dryland forests initiative: A market focused durable eucalypt R&D project. In L Apiolaza, S Chauhan, J Walker (Eds.), Revisiting eucalypts 2009 : Workshop proceedings, (pp. 57–74). Christchurch: Wood Technology Research Centre, Univeristy of Canterbury.

Miller, JT, Cannon, P, Ecroyd, CE (1992). Introduced forest trees in New Zealand: Recognition, role, and seed source. 11. Eucalyptus nitens (Deane et maiden) maiden. (FRI Bulletin 124). Rotorua: New Zeland Forest Research Institute.

Miller, JT, Hay, AE, Ecroyd, CE (2000). Introduced forest trees in New Zealand: Recognition, role, and seed source. 18. Ash eucalypts. (FRI Bulletin 124). Rotorua: New Zealand Forest Research Institute.

Millner, J. (2006). The performance of eucalyptus species in hill country. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Massey University.

MPI (2016). National exotic forest description (NEFD). Wellington: Ministry for Primary Industries.

Murphy, TN, Henson, M, Vanclay, JK. (2005). Growth stress in Eucalyptus dunnii. Australian Forestry, 68(2), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049158.2005.10674958.

Okuyama, T, Yamamoto, H, Yoshida, M, Hattori, Y, Archer, R. (1994). Growth stresses in tension wood: Role of microfibrils and lignification. Annales des Sciences Forestières, 51(3), 291–300.

Ozarska, B. (1999). A review of the utilisation of hardwoods for LVL. Wood Science and Technology, 33(4), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002260050120.

Page, D, & Singh, T. (2014). Durability of New Zealand grown timbers. New Zealand Journal of Forestry, 58(4), 26–30.

Palma, HAL, & Ballarin, AW. (2011). Physical and mechanical properties of LVL panels made from Eucalyptus grandis. Ciência Florestal, 21(3), 559–566. https://doi.org/10.5902/198050983813.

Poynton, RJ (1979). Eucalyptus globoidea Blakely. In RJ Poynton (Ed.), Tree planting in southern Africa: The eucalypts, (pp. 316–324). South Africa: Department of Forestry.

Shelbourne, C, Bulloch, B, Low, C, McConnochie, R. (2002). Performance to age 22 years of 49 eucalypts in the Wairarapa district, New Zealand, reviewed with results from other trials. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 32(2), 256–278.

Simmonds, JH (1927). Trees from other lands for shelter and timber in New Zealand: Eucalypts. Auckland: Brett Printing and Publishing Company.

Suontama, M, Low, CB, Stovold, GT, Miller, MA, Fleet, KR, Li, Y, Dungey, HS. (2015). Genetic parameters and genetic gains across three breeding cycles for growth and form traits of Eucalyptus regnans in New Zealand. Tree Genetics & Genomes, 11(6), 133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-015-0957-8.

Telfer, EJ, Stovold, GT, Li, YJ, Silva, OB, Grattapaglia, DG, Dungey, HS. (2015). Parentage reconstruction in Eucalyptus nitens using SNPs and microsatellite markers: A comparative analysis of marker data power and robustness. PLoS One, 10(7), e0130601. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130601.

Toba, K, Yamamoto, H, Yoshida, M. (2013). Micromechanical detection of growth stress in wood cell wall by wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAX). Holzforschung, 67(3), 315–323.

Turnbull, J (2007). Development of sustainable forestry plantations in China: A review. (impact assessment series report no. 45). Canberra: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

Valencia, J, Harwood, C, Washusen, R, Morrow, A, Wood, M, Volker, P. (2011). Longitudinal growth strain as a log and wood quality predictor for plantation-grown Eucalyptus nitens sawlogs. Wood Science and Technology, 45(1), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00226-010-0302-1.

Van Ballekom, S., & Millen, P. NZDFI: Achievements, constraints and opportunities. In CM Altaner, TJ Murray, & J Morgenroth (Eds.), Durable eucalypts on drylands: Protecting and enhancing value, Blenheim, New Zealand, 2017 (pp. 1-11): New Zealand School of Forestry

Van de Kuilen, JWG, Ceccotti, A, Xia, Z, He, M. (2011). Very tall wooden buildings with cross laminated timber. Procedia Engineering, 14, 1621–1628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.07.204.

Yang, JL, Baillères, H, Evans, R, Downes, G. (2006). Evaluating growth strain of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. From SilviScan measurements. Holzforschung, 60(5), 574–579.

Yang, JL, Baillères, H, Okuyama, T, Muneri, A, Downes, G. (2005). Measurement methods for longitudinal surface strain in trees: A review. Australian Forestry, 68(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049158.2005.10676224.

Yang, J, & Pongracic, S (2004). The impact of growth stress on sawn distortion and log end splitting of 32-year old plantation blue gum. (project no: PN03.1312). Vicroria: Forest and Wood Products Research & Development Corporation.

Yang, JL, & Waugh, G. (2001). Growth stress, its measurement and effects. Australian Forestry, 64(2), 127–135.

Yu, Y, Ren, D, Zhou, Y, Yu, W. (2006). Preliminary study on gluability of E. urophylla veneer. China Forest Products Industry, 33(4), 20–23.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Richard Barry from Nelson Pine Industries for overseeing the veneer peeling and LVL testing as well as for his contributions to the manuscript. Paul Millen's coordination in harvesting the trees is also appreciated.

Funding

This research project was financially supported by the Ministry of Primary Industries’ Sustainable Farming Fund (SFF407602). FG would also like to thank the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC) for supporting his study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FG carried out the field work, growth-strain measurement, veneer peeling, data analysis and prepared the manuscript. CMA designed and organised the study contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, F., Altaner, C.M. Properties of rotary peeled veneer and laminated veneer lumber (LVL) from New Zealand grown Eucalyptus globoidea. N.Z. j. of For. Sci. 48, 3 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-018-0109-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-018-0109-7