Abstract

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative disease associated with exposure to repetitive head impacts (RHI) and characterized by perivascular accumulations of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (p-tau) at the depths of the cortical sulci. Studies of living athletes exposed to RHI, including concussive and nonconcussive impacts, have shown increased blood–brain barrier permeability, reduced cerebral blood flow, and alterations in vasoreactivity. Blood–brain barrier abnormalities have also been reported in individuals neuropathologically diagnosed with CTE. To further investigate the three-dimensional microvascular changes in individuals diagnosed with CTE and controls, we used SHIELD tissue processing and passive delipidation to optically clear and label blocks of postmortem human dorsolateral frontal cortex. We used fluorescent confocal microscopy to quantitate vascular branch density and fraction volume. We compared the findings in 41 male brain donors, age at death 31–89 years, mean age 64 years, including 12 donors with low CTE (McKee stage I–II), 13 with high CTE (McKee stage III–IV) to 16 age- and sex-matched non-CTE controls (7 with RHI exposure and 9 with no RHI exposure). The density of vessel branches in the gray matter sulcus was significantly greater in CTE cases than in controls. The ratios of sulcus versus gyrus vessel branch density and fraction volume were also greater in CTE than in controls and significantly above one for the CTE group. Hyperphosphorylated tau pathology density correlated with gray matter sulcus fraction volume. These findings point towards increased vascular coverage and branching in the dorsolateral frontal cortex (DLF) sulci in CTE, that correlates with p-tau pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive neurodegenerative tauopathy caused in part by exposure to repetitive head impacts (RHI), such as those experienced through contact sport participation, military combat, and physical violence [49, 51, 54, 67]. RHI are a form of multiple brain injuries that include symptomatic concussion, characterized by symptoms such as headache, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and sleep disturbances, and non-concussive asymptomatic head impacts. A definitive diagnosis of CTE requires post-mortem neuropathological exam and the presence of the pathognomonic lesion, a perivascular accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) aggregates in neurons, with or without astrocytic p-tau inclusions, at the depths of the cortical sulci [11, 50]. In 2013, McKee and colleagues proposed a staging scheme to characterize the severity of the p-tau pathology in CTE, stages I–IV, based on the density and regional deposition of p-tau pathology [4, 8].

Several studies have demonstrated a dose–response relationship between the duration of exposure to RHI and risk for CTE and CTE severity [4, 51, 53, 54, 56, 57]. In addition, the location of the diagnostic perivascular lesions of CTE at the sulcal depths of the frontal cortex parallels the areas of greatest tissue deformation and strain in computational and finite element models of helmeted head impact injury [14, 21, 83]. Exposure to RHI and CTE are also associated with increases in neuroinflammation that parallels the severity of p-tau pathology and correlates with years of RHI exposure [18].

Vascular dysfunction and injury have been observed after mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI), RHI, and in CTE. Breakdown of the blood–brain barrier has been shown in the acute period in TBI-exposed mice [10], after mTBI in rodent models [28, 36, 71, 80, 81], and in the context of RHI in football players [75]. Reduced blood–brain barrier permeability regulator levels have been found in regions of high p-tau pathology in an individual with pathologically verified CTE [24] and in the serum of military personnel after acute repetitive blast exposure [2]. Markers of vascular injury were increased in the dorsolateral frontal cortex (DLF) of individuals with CTE [38]. Vascular dysfunction in rodent models includes reduced meningeal lymphatic drainage up to at least one month-post TBI [13] and reduced vasoreactivity after mTBI and RHI [31, 47]. In addition, decreased cerebral blood flow has been observed after single mTBI exposure in mice [32, 33, 79], RHI exposure in mice [1, 46], mTBI patients [42], and in elite rugby players [84].

Cerebrovascular structural changes have also been observed in mTBI, RHI, and CTE. Twenty-four hours after mTBI in rodents, microscopic changes can be seen, including microvascular degeneration, vascular cell apoptosis [37], and decreased vessel density compared to controls [45]. In the post-acute period in mouse models, cerebrovascular volume is increased after exposure to RHI [1] and mTBI [34, 80]. In humans, traumatic microbleeds can be found after acute TBI [30], and individuals with CTE show a propensity toward comorbid arteriolosclerosis [7]. RHI exposure has been associated with increased white matter hyperintensities on FLAIR magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), possibly due to microvascular injury [5, 74]. Microvascular abnormalities have also been observed in postmortem brain of individuals with CTE [7, 52, 53, 69]. Studies of the chronic effects of repetitive mTBI on vascular morphology in human subjects have demonstrated an expanded perivascular space around large caliber vessels on MRI [64]. Given the evidence for vascular structural changes, functional alterations and cognitive impairment in rodent models [42, 46, 78] and vascular comorbidities in human subjects with CTE, we sought to investigate the vascular changes in CTE DLF cortex using fluorescent microscopy and three-dimensional (3-D) imaging of blood vessel morphology within optically cleared tissue blocks.

Light microscopic studies are limited in detecting and quantifying morphologic changes in brain capillaries due to the sparse sampling of vascular cross-sections in two dimensions. In contrast, tissue clearing methods are well suited for characterizing small 3-D structures in the brain, as light scattering is minimized and vascular branching can be assessed using 200 µm tissue sections. Electrophoresis-driven clearing and fluorescent labeling have been successfully employed to image whole mouse brains [19, 37, 82] and many human organs, including the kidney, pancreas, heart, lung, spleen, and brain [48, 68]. Previous studies clearing postmortem human brain sections have either required minimal fixation, several months of clearing [20, 41, 43, 44, 60, 63], or the use of 100 µm sections cleared over a few weeks that warped the tissue surface [61]. The utility of tissue clearing has been demonstrated through the qualitative visualization of Alzheimer's Disease (AD) plaques in the human brain [8]. Recently, SHIELD postfixation has been developed for single cell three-dimensional microscopy with various methods of tissue clearing [62].

Here, we applied SHIELD, tissue clearing and staining protocols over 2 weeks using 200 µm thick slices of postmortem human brain to visualize DLF capillary morphology in brain donors with and without CTE.

Materials and methods

Study design and brain donors

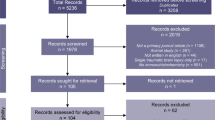

Autopsy participants included 41 male brain donors from three brain banks housed at VA Boston Healthcare System with harmonized neuropathological processing protocols and diagnostic procedures: Understanding Neurological Injury and Traumatic Encephalopathy (UNITE, n = 31), Boston University Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (ADRC, n = 1) and the National Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Brain Bank (PTSD, n = 9). For this study, participants were categorized based on their CTE diagnosis into two groups: "non-CTE" (n = 16) and "CTE" (high and low severity), n = 25. Participants were excluded if there was neuropathological evidence of co-morbid neurodegenerative disease [i.e. Alzheimer's disease, Lewy body disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, significant vascular disease (including infarcts, microinfarcts, and lacunes in the DLF) or causes of death that might affect tissue integrity (e.g., gunshot wounds to the head, drowning) as well as for missing primary study variables (CTE severity, CAA status)]. Participants with arteriolosclerosis and/or mild to moderate atherosclerosis were included and adjusted for statistically. Participants' causes of death and comorbidities are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. The donors' next of kin provided consent for brain donation and research participation. Institutional review boards from the Boston University Medical Center approved brain donation, postmortem clinical record review, neuropathological evaluation, and clinical interviews with donor family members.

Clinical assessment and diagnosis

Demographic information, medical history, and other antemortem clinical variables were obtained during retrospective clinical evaluation with informants for all brain donors and included a detailed assessment of RHI exposure, including sports played, primary sport, position, age at first exposure, years played, concussion history, and all other TBI history [58].

Tissue processing and pathological assessment

Postmortem brain tissue was fixed in periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde (PLP) for at least 3 months at 4 °C. The neuropathological assessment was performed using procedures previously established [58, 76]. Neuropathological evaluations were made by board-certified neuropathologists (ACM, TDS, BRH) according to published diagnostic criteria and were kept blinded to antemortem clinical information [58]. Cerebral arteriolosclerosis, atherosclerosis, and CAA were evaluated on a semiquantitative scale [12, 73].

For immunohistochemical assessment, 20 µm slides from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from the DLF were prepared and stained for AT8 as previously described [16]. Slides were scanned, digitized at 20× magnification, and analyzed for AT8 density (total area in the sulcus positive for AT8 staining divided by the total area of tissue analyzed) using Aperio Scanscope (Leica) as previously described [17]. The depth of the cortical sulcus was defined as the bottom third of two connecting gyri. Ki67 staining was completed using Leica’s Ready-to-Use Ki67 antibody reagent on the BOND staining system (Leica, Deer Park, IL) and imaged on the Vectra Polaris slide scanner (Akoya, Marlborough, MA).

Passive tissue clearing and labeling

PLP-fixed DLF (Brodmann area 46) tissue blocks were harvested with a 16mm2 leather punch with a thickness of 3 mm. Tissue harvesting was performed blinded to CTE status based on a standardized blocking scheme that is used in al cases. The 16 × 16 × 3 mm tissue sections were incubated in SHIELD OFF solution (LifeCanvas SHIELD-buffer solution, LifeCanvas SHIELD-Epoxy solution, and deionized water) for three days with shaking at 4 °C, transferred to SHIELD ON buffer and incubated for 24 h with shaking at 37 °C, and stored in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 0.02% sodium azide for up to several weeks. SHIELD-preserved sections were embedded in 2% agarose gel and cut into 200 µm slices using a vibratome (VF-700-0Z Microtome, Precisionary Instruments, Inc, Natick, MA). Slices were stored in PBS with 0.02% sodium azide. To delipidate, slices were incubated overnight at 37 °C with light shaking in passive clearing buffer [300 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10 mM boric acid, 100 mM sodium sulfite, pH 9]. Slices were subsequently washed twice with PBST (PBS + 0.4% Triton-X) at room temperature with light shaking to wash out the SDS then photobleached for five days in PBST as previously described [40]. Slices were incubated with 40 µg tomato lectin649 in 1 mL of PBST for 24 h with light shaking. Samples were washed three times with PBST for 30 min and incubated overnight in 4% PFA (Affymetrix) to post-fix the dye to the tissue. The next day the samples were washed three times, two hours per wash, in PBS. Samples were incubated overnight in EasyIndex (LifeCanvas) before mounting onto a 25 × 75 × 1.0 mm glass slide (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) and covered with a No. 1 22 × 30 mm glass coverslip (Corning GlassWorks, Corning, NY). Imaging was performed with a Nikon Eclipse Ti2-E spinning disk confocal microscope and Nikon Elements software (Nikon, Melville, NY) (Fig. 1).

Workflow for tissue clearing and staining. a Before the clearing process, tissue is prepared for clearing by cross-linking proteins and nucleic acids using epoxides. This cross-linking provides increased structural stability in preparation of lipid removal from the tissue [62]. Lipids are washed from the tissue using sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS). The fully cleared tissue can be fluorescently labeled and incubated in an index of refraction matching solution so that its refractive index matches that of a glass cover-slip. b Passive tissue clearing is diffusion based using a floating sections protocol. c Fluorescent molecules diffuse to their target sites in the floating section. d After the fluorescent dyes have been fixed in place and the sample has been refractive-index (RI) matched to the glass coverslip, the tissue becomes translucent. Fluorophores can be visualized at any point in the Z-dimension of the respective samples. Created with www.BioRender.com

Imaging of cleared tissue

Tomato lectin649 was excited using the 633 nm laser line of a Celesta light source, at 72.8% power with an exposure time of 400 ms. A Plan Apo λ 20 × air objective (Nikon, Melville, NY) was used to acquire up to four regions each in the gray matter crest, gray matter sulcus, white matter crest, and white matter sulcus. Sulcus imaging regions were randomly selected in the bottom third of two connecting gyri, and crest imaging regions were randomly selected in the top third of the gyrus. For each image stack, image slices were taken 0.9 µm apart. To capture the highest resolution images, we used a Plan Apo λ 60 × oil-immersion objective (Nikon, Melville, NY). Tissue imaging and image analysis were performed blinded to CTE status.

Quantification of blood vessels and variables measured using fluorescence microscopy

Passively cleared DLF samples were quantified using Imaris 9.6 and 9.7 (Oxford Instruments, Abington, Oxfordshire UK), (Table 1). For each image, a surface was generated in Imaris using the Surface Tool to represent blood vessels based on fluorescent intensity and volume. Pixels outside of the generated surface were set to zero to eliminate non-specific background fluorescence. The volume of that surface divided by the total volume of the image stack represented the unitless fraction volume calculation. Blood vessel branches were drawn manually using the Imaris Filament Tool. The total number of drawn filament segments was divided by the total volume of the image stack to calculate branch density in units of branches/µm3. For each case, the fraction volume and branch density measurements were an average of the measurements made from the replicate image stacks per region.

In order to quantify differences in vascular morphology, we quantified blood vessel branch density via the number of blood vessel branches per unit volume. We used blood vessel fraction volume, the fraction of the image volume composed of blood vessels, to quantify vascular coverage. Because the pathognomonic CTE lesion is in sulcal depths, we compared measurements in the sulcus vs the gyrus. Similarly we correlated the vascular fraction volume and branch density with p-tau pathology to determine if p-tau accumulation colocalized with altered vascular morphology.

Statistical analyses

The fluorescence microscopy data were analyzed using SPSS (v.27, IBM, Inc, Armonk, NY) and GraphPad Prism (v.9.0.0, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare fraction volume or branch density changes among control and CTE groups. Age at death was included in all analyses as a covariate to control for age-associated differences. Arteriolosclerosis and atherosclerosis were not included as covariates, as the F-statistic was not significant for any measured variables. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) was also included as a covariate. Associations among p-tau burden and vascular variables were measured with multiple linear regression models with p-tau staining density, age of death, and CTE status as the independent variables and gray matter vessel fraction volume or branch density as the dependent variable. Cases with p-tau staining data were those with CTE (n = 22) and a subset of non-CTE controls (n = 8). Descriptive statistics were generated with SPSS. The significance level was set a priori to 5%. Statistical power was calculated with MATLAB 2020a’s samplesizepwr function. The full dataset with clinical, neuropathological, and measured vascular variables can be found in Additional file 2.

Results

Demographic statistics of experimental groups

Experimental groups were all male did not differ in mean age at death (Table 2). Individual participants may have more than one RHI exposure source.

Visualization of microvascular networks with tomato lectin649 fluorescence (Fig. 2)

Images of blood vessels labeled with tomato lectin649 (green) in cleared and labeled PLP-fixed human DLF tissue. a 200 µm thick DLF tissue section after clearing and staining with tomato lectin649, imaged at 4x. Overlaid squares represent the areas sampled per case: gray matter crest (red), white matter crest (white), gray matter sulcus (red dashed), and white matter sulcus (white dashed). 20 × images of each region are shown at top, dimension of each 347 × 336 × 91 µm. b 20 × image of a branching blood vessel and 60 × optical slices taken at 9 µm (c), 27.6 µm (d), and 35.4 µm into the tissue slice (e). f and g both show 20 × images of passively cleared and tomato lectin649-stained DLF tissue from different cases in the gray matter sulcus. A CTE case with high blood vessel fraction volume and branch density is shown in (f), with fraction volumes of 0.10 and and branch densitiy of 1500 branches/mm3. g shows an image stack from a non-CTEcontrol with lower vessel fraction volume (of 0.069) and branch density (980 branches/mm3). Each image stack is 81 µm thick

SHIELD tissue treatment, passive delipidation, and staining was successful for visualizing blood vessels in three dimensions. The patterns of tomato lectin649 fluorescence were distinctive in the gray and white matter, with many branching curving vessels in the gray matter and more linear vessels in the white matter with fewer branches (Fig. 2a, top). As seen in Fig. 2b–e, a branching blood vessel visualized in a single plane can appear as either one (Fig. 2c), an individual vessel with multiple lumina (Fig. 2d), or as two vessels (Fig. 2e) depending on the focal plane. Imaging a 200 µm tissue section allows visualization of the vessel in 3-D and captures vascular branching points and vascular network structure.

CTE is associated with increased vascular branching in the gray matter sulcus

Vascular density and blood vessel branching could be qualitatively observed in image stacks of at least 100 µm thickness. In general, blood vessel density was greater, and there were more branching blood vessels in CTE compared to control cases (Fig. 2f–g). Blood vessel branch density was increased in the DLF gray matter sulcus of the CTE group compared to the control group. Means of blood vessel branch densities were compared using an ANCOVA with the age of death as a covariate. The CTE group had a 24% higher branch density than the controls. Gray matter sulcus branch density of the CTE group (1180 ± 40 branches/mm3) was significantly higher than controls (950 ± 50 branches/mm3), p = 0.0011. The statistical power for this difference was 0.9963. There were no significant differences in blood vessel branch density among groups in the white matter. The significance between groups was unaffected whether or not CAA, arteriolosclerosis, and atherosclerosis were included as covariates.

Vascular branching and density are greater in the sulcus than the crest in CTE but not controls

We compared vascular density and branching in the sulcal depth to that in the gyral crest by dividing the mean branch density and fraction volume in the sulcus by the measurements in the crest for each case. The group means of the calculated ratio were compared between groups with ANCOVA using the age of death as a covariate. The ratio of gray matter blood vessel branch density in the sulcus compared to the crest was 1.25 ± 0.04 for the CTE group and 1.04 ± 0.06 for the control group, a significant difference (p = 0.0076) with a power of 0.9613, (Fig. 3b).

Quantification of DLF vascular branching and coverage. Differences between groups were established by ANCOVA with means adjusted for evaluation at mean age of death = 64.2 years and CAA = 0.3659. The gray matter branch density and fraction volume ratios were calculated by dividing the branch density or fraction volume of the sulcus by the branch density or fraction volume of the crest. a Gray matter sulcus branch density, b Gray matter branch density ratio c Gray matter fraction volume ratio. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. CTE n = 25, controls n = 15

The CTE group also had a higher ratio of sulcus:crest fraction volume than controls. Controls showed a fraction volume of 1.00 ± 0.05. The CTE group had a significantly greater fraction volume ratio, 1.15 ± 0.04, p = 0.0336, (Fig. 3c). The statistical power of this difference was 0.8445. No significant differences between CTE and controls were seen with the blood vessel branch density ratios or fraction volume in the white matter. Arteriolosclerosis and atherosclerosis were not significant predictors of blood vessel fraction volume ratio or blood vessel branch density ratio.

CTE is associated with greater vascular coverage in the absence of CAA

When cases with CAA were removed from the analysis, CTE cases had a higher gray matter sulcus fraction volume than control cases. With our full dataset, changes in fraction volume were driven primarily by CAA (p = 0.007 for gray matter sulcus fraction volume), as calculated via ANCOVA with the age of death as a covariate comparing groups with and without CAA. As CAA is characterized by amyloid-beta deposits in the vessel walls, it is likely that there is a greater fraction volume detected in CAA cases because of the thickened vessel walls. To eliminate the effect of CAA on comparisons between CTE and controls, cases with CAA were eliminated from the analysis such that n = 13 control cases without CAA and n = 17 CTE cases without CAA. With this subset of data, there was a 17% increase (p = 0.0282) in gray matter sulcus vessel fraction volume of CTE cases compared to controls (Fig. 4a). Removing cases with CAA did not take away statistical significance from any of the other comparisons of measured vascular variables (Fig. 4b–d).

Quantification of DLF vascular branching and coverage in cases without CAA. Differences between groups were established by ANCOVA with means adjusted for evaluation at mean age of death = 61.4 years. The gray matter branch density and fraction volume ratios were calculated by dividing the branch density or fraction volume of the sulcus by the branch density or fraction volume of the crest. a vessel fraction volume in the gray matter sulcus, b vessel branch density in the gray matter sulcus, c gray matter fraction volume ratio, and d gray matter branch density ratio. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. CTE n = 17, controls n = 13

P-tau pathology correlates with increased DLF gray matter vascular density

We compared p-tau pathology with blood vessel branch density and fraction volume in the gray matter sulcus. We pooled the control and CTE groups and conducted multiple linear regression with the age of death and CTE status as a covariate, p-tau staining density as the independent variable, and branch density or fraction volume as the dependent variable. P-tau staining density in the sulcus correlated positively with sulcal gray matter fraction volume (Table 3). The correlation coefficient between the two variables was 0.472 with a corresponding p-value of 0.013 (indicated in bold). Age at death did not significantly predict gray matter fraction volume or branch density. The correlation between AT8 staining density and gray matter sulcus fraction volume was not driven by CTE status.

Discussion

Using SHIELD postfixation and passive delipidation, we found increased vascular branching and coverage in the gray matter sulcus in CTE and increased vascular branching and coverage in the sulcus compared to the crest in CTE. We also found that vascular coverage in the sulcus correlated with p-tau pathology. These findings suggest that there is increased vascular branching and coverage in regions with p-tau pathology in CTE. Figure 5 outlines vascular branching in the DLF gray matter sulcus as seen in our measurements.

Vascular branching and coverage in the setting of repetitive head impacts and CTE. Scheme for the association between vascular branching, RHI, and CTE in the DLF gray matter sulcus. Illustrations representing a controls and b CTE cases. Each illustration is paired with a 347 µm × 335 µm × 81 µm fluorescent tomato lectin649 (green) image stack of DLF gray matter sulcus tissue from a representative case. As reflected in our data, b shows a significantly higher branch density in the sulcus than a

The increased vessel branching and coverage found in DLF gray matter sulcus in CTE may be explained by prior angiogenesis. Cortical neovascularization may be a chronically active process that occurs in parallel with CTE p-tau pathology development and progression. The combination of direct injury to vascular endothelial cells, inflammation, and secondary tissue hypoxia creates a proangiogenic environment. Chronic neuroinflammation and tissue hypoxia due to compromised vasculature results in the release of proangiogenic proteins [3, 9, 25, 59, 66, 70]. Neoangiogenic processes are activated by inadequate tissue oxygenation and hypoxia to increase vascular coverage [65]. RHI itself may also induce angiogenesis mechanically [29, 35]. Military veterans that have mTBI from blast exposure have increased serum concentrations of vascular endothelia growth factor (VEGF-A), indicating a correlation between mTBI and pro-angiogenic signaling [55]. Molecular markers of vascular injury have also been observed in tissue from the biorepositories used in this study [38]. The observed increased vessel branch density in CTE cases compared to controls supports prior angiogenesis due to the branching progression of new vessel formation [15, 23, 65]. If the increased branching observed in CTE cases is due to angiogenesis, it is likely to have occurred in the distant past. None of our cases showed positive staining for Ki67, a marker of cellular proliferation (Additional file 3: Supplementary Fig. S1). Another putative line of evidence for prior angiogenesis is increased vascular coverage, measured as increased vessel fraction volume. The ratios of gray matter branch density and fraction volume were greater than 1 in CTE but below 1 in controls, suggesting that sulcus-specific increased vascular branching and coverage are associated with CTE. Previous antemortem MRI work has highlighted the susceptibility of blood vessels in the gray matter sulci to damage as a result of impact forces [39]. In CTE, gray matter sulci have been exposed to repetitive forces and secondary hypoxia from vessel damage that creates a proangiogenic environment. Cortical neovascularization may be a chronically active process that occurs in parallel with CTE p-tau pathology development and progression.

The observed increase in vessel branching and fraction volume in the sulcus compared to the crest may also be due to atrophy of surrounding brain tissue. Lower volumes of gray matter and white matter in the cortical sulci have been observed in individuals exposed to TBI compared to unexposed controls [22]. Individuals with postmortem neuropathologically diagnosed CTE also had more atrophy in the frontal cortex, visualized with antemortem MRI, compared to controls [6]. It is possible that there are more vessel branches per unit volume in CTE cases compared to controls, because there is less surrounding tissue to contribute to the total unit volume.

There was a correlation between p-tau density with increased vascular fraction volume in the gray matter sulci of individuals with exposure to RHI. This correlation suggests potential prior vascular remodeling and/or tissue atrophy of high p-tau burden in CTE. Vascular remodeling and p-tau accumulation may be dependent or independent, as mechanical force alone is enough to cause tau mislocalization and expression of pro-angiogenic factors in vitro [14, 29].

Furthermore, this work demonstrates that microvascular networks in postmortem human brain tissue preserved for years in paraformaldehyde can be cleared, labeled, and confocally imaged in three dimensions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using tissue clearing to probe human disease using banked, long-term fixed brain tissue with quantitative results.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this work. Changes in vascular branching in the white matter were not detected by our techniques because the fraction volume and branch density of white matter vasculature was lower and dominated by a smaller number of larger vessels. Imaging greater volumes of tissue would be needed to robustly detect white matter changes. While the technique used here is well suited to the microvasculature, lower magnification optical coherence tomography is better for visualization of larger white matter vessels [72, 77]. Moreover, there are unavoidable drawbacks to using postmortem human tissue such as varying tissue extraction and fixation conditions, small sample size, comorbidities, clinical data collection, and convenience sampling. Although we adjusted for age, confounding by age may exist because the age ranges do not entirely overlap. We addressed comorbidities by statistically determining which comorbidities affected our data and included them in the models as covariates. The diversity of the study population was constrained by the tissue available in the UNITE and PTSD brain banks. Future work should include participants of all genders and races as more tissue is available.

Future directions

The results of this research suggest several avenues for future inquiry. The sulcus-to-crest ratios of vascular branching and fraction volume are worth further exploration for possible use in clinical diagnosis. In addition, since small vascular disease or arteriolosclerosis is associated with dementia in CTE [7, 26], future work will help determine whether the vascular changes found in this work are also associated with cognitive impairment. The SHIELD tissue post-fixing and clearing techniques used here could also be combined with immunofluorescence to evaluate multiple markers in future studies.

Conclusions

We used tissue clearing to measure and compare vascular coverage and branching in postmortem brain tissue from individuals with CTE and controls. Our work suggests an association between vascular branching and density and CTE. Sulcus-specific vascular coverage increases also correlated positively with p-tau pathology providing further evidence to suggest that microvascular abnormalities and p-tau pathology might be mechanistically linked in CTE.

Availability of data and materials

The raw images analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The dataset quantified from the images in the current study is available online (Additional file 2).

References

Adams C, Bazzigaluppi P, Beckett TL, Bishay J, Weisspapir I, Dorr A, Mester JR, Steinman J, Hirschler L, Warnking JM, Barbier EL, McLaurin J, Sled JG, Stefanovic B (2018) Neurogliovascular dysfunction in a model of repeated traumatic brain injury. Theranostics 8:4824–4836. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.24747

Agoston DV, McCullough J, Aniceto R, Lin I-H, Kamnaksh A, Eklund M, Graves WM, Dunbar C, Engall J, Schneider EB, Leonessa F, Duckworth JL (2022) Blood-based biomarkers of repetitive, subconcussive blast overpressure exposure in the training environment: a pilot study. Neurotrauma Rep 3:479–490. https://doi.org/10.1089/neur.2022.0029

Alford PW, Dabiri BE, Goss JA, Hemphill MA, Brigham MD, Parker KK (2011) Blast-induced phenotypic switching in cerebral vasospasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:12705–12710. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1105860108

Alosco ML, Cherry JD, Huber BR, Tripodis Y, Baucom Z, Kowall NW, Saltiel N, Goldstein LE, Katz DI, Dwyer B, Daneshvar DH, Palmisano JN, Martin B, Cantu RC, Stern RA, Alvarez VE, Mez J, Stein TD, McKee AC (2020) Characterizing tau deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE): utility of the McKee CTE staging scheme. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-020-02197-9

Alosco ML, Koerte IK, Tripodis Y, Mariani M, Chua AS, Jarnagin J, Rahimpour Y, Puzo C, Healy RC, Martin B, Chaisson CE, Cantu RC, Au R, McClean M, McKee AC, Lin AP, Shenton ME, Killiany RJ, Stern RA (2018) White matter signal abnormalities in former National Football League players. Alzheimers Dement Diagn Assess Dis Monit 10:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2017.10.003

Alosco ML, Mian AZ, Buch K, Farris CW, Uretsky M, Tripodis Y, Baucom Z, Martin B, Palmisano J, Puzo C, Ang TFA, Joshi P, Goldstein LE, Au R, Katz DI, Dwyer B, Daneshvar DH, Nowinski C, Cantu RC, Kowall NW, Huber BR, Alvarez VE, Stern RA, Stein TD, Killiany RJ, McKee AC, Mez J (2021) Structural MRI profiles and tau correlates of atrophy in autopsy-confirmed CTE. Alzheimers Res Ther 13:193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-021-00928-y

Alosco ML, Stein TD, Tripodis Y, Chua AS, Kowall NW, Huber BR, Goldstein LE, Cantu RC, Katz DI, Palmisano JN (2019) Association of white matter rarefaction, arteriolosclerosis, and tau with dementia in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. JAMA Neurol 76:1298–1308

Ando K, Laborde Q, Lazar A, Godefroy D, Youssef I, Amar M, Pooler A, Potier M-C, Delatour B, Duyckaerts C (2014) Inside Alzheimer brain with CLARITY: senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and axons in 3-D. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 128:457–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-014-1322-y

Andrews AM, Lutton EM, Merkel SF, Razmpour R, Ramirez SH (2016) Mechanical injury induces brain endothelial-derived microvesicle release: implications for cerebral vascular injury during traumatic brain injury. Front Cell Neurosci 10:43

Bhowmick S, D’Mello V, Caruso D, Wallerstein A, Abdul-Muneer PM (2019) Impairment of pericyte-endothelium crosstalk leads to blood-brain barrier dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol 317:260–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.03.014

Bieniek KF, Cairns NJ, Crary JF, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Keene CD, Litvan I, Perl DP, Stein TD, Vonsattel J-P, Stewart W, Dams-O’Connor K, Gordon WA, Tripodis Y, Alvarez VE, Mez J, Alosco ML, McKee AC (2021) The second NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlab001

Blevins BL, Vinters HV, Love S, Wilcock DM, Grinberg LT, Schneider JA, Kalaria RN, Katsumata Y, Gold BT, Wang DJJ, Ma SJ, Shade LMP, Fardo DW, Hartz AMS, Jicha GA, Nelson KB, Magaki SD, Schmitt FA, Teylan MA, Ighodaro ET, Phe P, Abner EL, Cykowski MD, Van Eldik LJ, Nelson PT (2021) Brain arteriolosclerosis. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 141:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-020-02235-6

Bolte AC, Dutta AB, Hurt ME, Smirnov I, Kovacs MA, McKee CA, Ennerfelt HE, Shapiro D, Nguyen BH, Frost EL, Lammert CR, Kipnis J, Lukens JR (2020) Meningeal lymphatic dysfunction exacerbates traumatic brain injury pathogenesis. Nat Commun 11:4524. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18113-4

Braun NJ, Liao D, Alford PW (2021) Orientation of neurites influences severity of mechanically induced tau pathology. Biophys J 120:3272–3282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.07.011

Burri PH, Djonov V (2002) Intussusceptive angiogenesis––the alternative to capillary sprouting. Mol Aspects Med 23:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0098-2997(02)00096-1

Cherry JD, Meng G, Daley S, Xia W, Svirsky S, Alvarez VE, Nicks R, Pothast M, Kelley H, Huber B, Tripodis Y, Alosco ML, Mez J, McKee AC, Stein TD (2020) CCL2 is associated with microglia and macrophage recruitment in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuroinflammation 17:370. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-02036-4

Cherry JD, Stein TD, Tripodis Y, Alvarez VE, Huber BR, Au R, Kiernan PT, Daneshvar DH, Mez J, Solomon TM, Alosco ML, McKee AC (2017) CCL11 is increased in the CNS in chronic traumatic encephalopathy but not in Alzheimer’s disease. PLOS ONE 12:e0185541. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185541

Cherry JD, Tripodis Y, Alvarez VE, Huber B, Kiernan PT, Daneshvar DH, Mez J, Montenigro PH, Solomon TM, Alosco ML, Stern RA, McKee AC, Stein TD (2016) Microglial neuroinflammation contributes to tau accumulation in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun 4:112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-016-0382-8

Chung K, Deisseroth K (2013) CLARITY for mapping the nervous system. Nat Methods 10:508–513. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2481

Chung K, Wallace J, Kim S-Y, Kalyanasundaram S, Andalman AS, Davidson TJ, Mirzabekov JJ, Zalocusky KA, Mattis J, Denisin AK, Pak S, Bernstein H, Ramakrishnan C, Grosenick L, Gradinaru V, Deisseroth K (2013) Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature 497:332–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12107

Cloots RJH, Gervaise HMT, Van Dommelen JAW, Geers MGD (2008) Biomechanics of traumatic brain injury: influences of the morphologic heterogeneities of the cerebral cortex. Ann Biomed Eng 36:1203

Cole JH, Jolly A, De Simoni S, Bourke N, Patel MC, Scott G, Sharp DJ (2018) Spatial patterns of progressive brain volume loss after moderate-severe traumatic brain injury. Brain 141:822–836. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx354

Djonov V, Baum O, Burri PH (2003) Vascular remodeling by intussusceptive angiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res 314:107–117

Doherty CP, O’Keefe E, Wallace E, Loftus T, Keaney J, Kealy J, Humphries MM, Molloy MG, Meaney JF, Farrell M, Campbell M (2016) Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction as a Hallmark Pathology in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 75:656–662. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlw036

Fisher AB, Chien S, Barakat AI, Nerem RM (2001) Endothelial cellular response to altered shear stress. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281:L529–L533

Fuh J-L (2005) Neuropsychiatric profiles in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:1337–1341. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2004.056408

Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Janssen PL, Yuk FJ, Anazodo PC, Pricop PE, Paulino AJ, Wicinski B, Shaughness MC, Maudlin-Jeronimo E, Hall AA, Dickstein DL, McCarron RM, Chavko M, Hof PR, Ahlers ST, Elder GA (2014) Selective vulnerability of the cerebral vasculature to blast injury in a rat model of mild traumatic brain injury. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-5960-2-67

Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R, Perez Garcia GS, Perez GM, Searcy C, Vargas D, Spencer A, Janssen PL, Tschiffely AE, McCarron RM, Ache B, Manoharan R, Janssen WG, Tappan SJ, Hanson RW, Gandy S, Hof PR, Ahlers ST, Elder GA (2019) Low-level blast exposure disrupts gliovascular and neurovascular connections and induces a chronic vascular pathology in rat brain. Acta Neuropathol Commun 7:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0647-5

Gloe T, Sohn HY, Meininger GA, Pohl U (2002) Shear Stress-induced Release of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor from Endothelial Cells Is Mediated by Matrix Interaction via Integrin αVβ3. J Biol Chem 277:23453–23458. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M203889200

Griffin AD, Turtzo LC, Parikh GY, Tolpygo A, Lodato Z, Moses AD, Nair G, Perl DP, Edwards NA, Dardzinski BJ, Armstrong RC, Ray-Chaudhury A, Mitra PP, Latour LL (2019) Traumatic microbleeds suggest vascular injury and predict disability in traumatic brain injury. Brain 142:3550–3564. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz290

Griffiths DR, Law LM, Young C, Fuentes A, Truran S, Karamanova N, Bell LC, Turner G, Emerson H, Mastroeni D, Gonzales RJ, Reaven PD, Quarles CC, Migrino RQ, Lifshitz J (2022) Chronic cognitive and cerebrovascular function after mild traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurotrauma 39:1429–1441. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2022.0015

Han X, Chai Z, Ping X, Song L-J, Ma C, Ruan Y, Jin X (2020) In vivo two-photon imaging reveals acute cerebral vascular spasm and microthrombosis after mild traumatic brain injury in mice. Front Neurosci 14:210. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00210

Hanalioglu S, Hidayatov T, Isikay I, Cakir Aktas C, Yemisci M, Mut M (2022) Early cerebral blood flow changes, cerebrovascular reactivity and cortical spreading depolarizations in experimental mild traumatic brain injury model. Turk Neurosurg. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.37742-22.1

Hayward NMEA, Tuunanen PI, Immonen R, Ndode-Ekane XE, Pitkänen A, Gröhn O (2011) Magnetic resonance imaging of regional hemodynamic and cerebrovascular recovery after lateral fluid-percussion brain injury in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31:166–177. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2010.67

Hodivala-Dilke KM, Reynolds AR, Reynolds LE (2003) Integrins in angiogenesis: multitalented molecules in a balancing act. Cell Tissue Res 314:131–144

Hubbard B, Velmurugan GV, Brown E, Sullivan PG (2022) Resilience of females to acute blood-brain barrier damage and anxiety behavior following mild blast traumatic brain injury. In Review

Kim S-Y, Cho JH, Murray E, Bakh N, Choi H, Ohn K, Ruelas L, Hubbert A, McCue M, Vassallo SL, Keller PJ, Chung K (2015) Stochastic electrotransport selectively enhances the transport of highly electromobile molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112:E6274–E6283. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1510133112

Kirsch D, Shah A, Dixon E, Kelley H, Cherry JD, Xia W, Daley S, Aytan N, Cormier K, Kubilus C, Mathias R, Alvarez VE, Huber BR, McKee AC, Stein TD (2023) Vascular injury is associated with repetitive head impacts and tau pathology in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol Publish Ahead of Print. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlac122

Kornguth S, Rutledge N, Perlaza G, Bray J, Hardin A (2017) A proposed mechanism for development of CTE following concussive events: head impact, water hammer injury, neurofilament release, and autoimmune processes. Brain Sci 7:164. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7120164

Ku T, Guan W, Evans NB, Sohn CH, Albanese A, Kim J-G, Frosch MP, Chung K (2020) Elasticizing tissues for reversible shape transformation and accelerated molecular labeling. Nat Methods 17:609–613. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-020-0823-y

Lai HM, Liu AKL, Ng HHM, Goldfinger MH, Chau TW, DeFelice J, Tilley BS, Wong WM, Wu W, Gentleman SM (2018) Next generation histology methods for three-dimensional imaging of fresh and archival human brain tissues. Nat Commun 9:1066. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03359-w

Li F, Lu L, Shang S, Chen H, Wang P, Haidari NA, Chen Y-C, Yin X (2020) Cerebral blood flow and its connectivity deficits in mild traumatic brain injury at the acute stage. Neural Plast 2020:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2174371

Liebmann T, Renier N, Bettayeb K, Greengard P, Tessier-Lavigne M, Flajolet M (2016) Three-dimensional study of Alzheimer’s disease hallmarks using the iDISCO clearing method. Cell Rep 16:1138–1152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.060

Liu AKL, Hurry MED, Ng OTW, DeFelice J, Lai HM, Pearce RKB, Wong GT, Chang RC, Gentleman SM (2016) Bringing CLARITY to the human brain: visualization of Lewy pathology in three dimensions. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 42:573–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12293

Lu L, Steinman J, Sled JG, Mao H (2021) Brain microvascular damage linked to a moderate level of strain induced by controlled cortical impact. J Biomech 122:110452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110452

Lynch CE, Crynen G, Ferguson S, Mouzon B, Paris D, Ojo J, Leary P, Crawford F, Bachmeier C (2016) Chronic cerebrovascular abnormalities in a mouse model of repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 30:1414–1427. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2016.1219060

Lynch CE, Eisenbaum M, Algamal M, Balbi M, Ferguson S, Mouzon B, Saltiel N, Ojo J, Diaz-Arrastia R, Mullan M, Crawford F, Bachmeier C (2021) Impairment of cerebrovascular reactivity in response to hypercapnic challenge in a mouse model of repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 41:1362–1378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X20954015

Mai H, Rong Z, Zhao S, Cai R, Steinke H, Bechmann I, Ertürk A (2022) Scalable tissue labeling and clearing of intact human organs. Nat Protoc 17:2188–2215. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-022-00712-8

Martland HS (1928) Punch drunk. J Am Med Assoc 91:1103–1107. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1928.02700150029009

McKee AC, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Folkerth RD, Dirk Keene C, Litvan I, Perl DP, Stein TD, Vonsattel J-P, Stewart W, Tripodis Y, Crary JF, Bieniek KF, Dams-O’Connor K, Alvarez VE, Gordon WA (2016) The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 131:75–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1515-z

McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, Santini VE, Lee H-S, Kubilus CA, Stern RA (2009) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68:709–735

Mckee AC, Daneshvar DH (2015) Chapter 4—The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. In: Grafman J, Salazar AM (eds) Handbook of clinical neurology. Elsevier, pp 45–66

McKee AC, Stein TD, Kiernan PT, Alvarez VE (2015) The neuropathology of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain Pathol 25:350–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12248

McKee AC, Stein TD, Nowinski CJ, Stern RA, Daneshvar DH, Alvarez VE, Lee H-S, Hall G, Wojtowicz SM, Baugh CM, Riley DO, Kubilus CA, Cormier KA, Jacobs MA, Martin BR, Abraham CR, Ikezu T, Reichard RR, Wolozin BL, Budson AE, Goldstein LE, Kowall NW, Cantu RC (2013) The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 136:43–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws307

Meabon JS, Cook DG, Yagi M, Terry GE, Cross DJ, Muzi M, Pagulayan KF, Logsdon AF, Schindler AG, Ghai V, Wang K, Fallen S, Zhou Y, Kim T-K, Lee I, Banks WA, Carlson ES, Mayer C, Hendrickson RC, Raskind MA, Marshall DA, Perl DP, Keene CD, Peskind ER (2020) Chronic elevation of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) is associated with a history of blast exposure. J Neurol Sci 417:117049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2020.117049

Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Abdolmohammadi B, Chua AS, Alosco ML, Kiernan PT, Evers L, Marshall L, Martin BM, Palmisano JN, Nowinski CJ, Mahar I, Cherry JD, Alvarez VE, Dwyer B, Huber BR, Stein TD, Goldstein LE, Katz DI, Cantu RC, Au R, Kowall NW, Stern RA, McClean MD, Weuve J, Tripodis Y, McKee AC (2020) Duration of American Football Play and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Ann Neurol 87:116–131. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25611

Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, Abdolmohammadi B, Alvarez VE, Huber BR, Alosco ML, Solomon TM, Nowinski CJ, McHale L (2017) Clinicopathological evaluation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in players of American football. JAMA 318:360–370

Mez J, Solomon TM, Daneshvar DH, Murphy L, Kiernan PT, Montenigro PH, Kriegel J, Abdolmohammadi B, Fry B, Babcock KJ, Adams JW, Bourlas AP, Papadopoulos Z, McHale L, Ardaugh BM, Martin BR, Dixon D, Nowinski CJ, Chaisson C, Alvarez VE, Tripodis Y, Stein TD, Goldstein LE, Katz DI, Kowall NW, Cantu RC, Stern RA, McKee AC (2015) Assessing clinicopathological correlation in chronic traumatic encephalopathy: rationale and methods for the UNITE study. Alzheimers Res Ther 7:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-015-0148-8

Monson KL, Converse MI, Manley GT (2019) Cerebral blood vessel damage in traumatic brain injury. Clin Biomech 64:98–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.02.011

Morawski M, Kirilina E, Scherf N, Jäger C, Reimann K, Trampel R, Gavriilidis F, Geyer S, Biedermann B, Arendt T, Weiskopf N (2018) Developing 3D microscopy with CLARITY on human brain tissue: Towards a tool for informing and validating MRI-based histology. Neuroimage 182:417–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.060

Murray E, Cho JH, Goodwin D, Ku T, Swaney J, Kim S-Y, Choi H, Park Y-G, Park J-Y, Hubbert A, McCue M, Vassallo S, Bakh N, Frosch MP, Wedeen VJ, Seung HS, Chung K (2015) Simple, Scalable Proteomic Imaging for High-Dimensional Profiling of Intact Systems. Cell 163:1500–1514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.025

Park Y-G, Sohn CH, Chen R, McCue M, Yun DH, Drummond GT, Ku T, Evans NB, Oak HC, Trieu W, Choi H, Jin X, Lilascharoen V, Wang J, Truttmann MC, Qi HW, Ploegh HL, Golub TR, Chen S-C, Frosch MP, Kulik HJ, Lim BK, Chung K (2019) Protection of tissue physicochemical properties using polyfunctional crosslinkers. Nat Biotechnol 37:73–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4281

Phillips J, Laude A, Lightowlers R, Morris CM, Turnbull DM, Lax NZ (2016) Development of passive CLARITY and immunofluorescent labelling of multiple proteins in human cerebellum: understanding mechanisms of neurodegeneration in mitochondrial disease. Sci Rep 6:26013. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26013

Piantino J, Schwartz DL, Luther M, Newgard C, Silbert L, Raskind M, Pagulayan K, Kleinhans N, Iliff J, Peskind E (2021) Link between Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, Poor Sleep, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Visible Perivascular Spaces in Veterans. J Neurotrauma neu.2020.7447. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2020.7447

Plate KH (1999) Mechanisms of Angiogenesis in the Brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 58:313–320. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005072-199904000-00001

Proescholdt MA, Heiss JD, Walbridge S, Mühlhauser J, Capogrossi MC, Oldfield EH, Merrill MJ (1999) Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Modulates Vascular Permeability and Inflammation in Rat Brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 58:613–627. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005072-199906000-00006

Roberts GW, Whitwell HL, Acland PR, Bruton CJ (1990) Dementia in a punch-drunk wife. The Lancet 335:918–919

Shi L, Wei M, Miao Y, Qian N, Shi L, Singer RA, Benninger RKP, Min W (2022) Highly-multiplexed volumetric mapping with Raman dye imaging and tissue clearing. Nat Biotechnol 40:364–373. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-01041-z

Silver JM, McAllister TW, Yudofsky SC (2005) Textbook of traumatic brain injury, 1st edn. American Psychiatric Pub, Washington

Snyder B, Shell B, Cunningham JT, Cunningham RL (2017) Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces oxidative stress and inflammation in brain regions associated with early-stage neurodegeneration. Physiol Rep 5:e13258. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13258

Tagge CA, Fisher AM, Minaeva OV, Gaudreau-Balderrama A, Moncaster JA, Zhang X-L, Wojnarowicz MW, Casey N, Lu H, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Saman S, Ericsson M, Onos KD, Veksler R, Senatorov VV, Kondo A, Zhou XZ, Miry O, Vose LR, Gopaul KR, Upreti C, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, Alvarez VE, Hildebrandt AM, Franz ES, Konrad J, Hamilton JA, Hua N, Tripodis Y, Anderson AT, Howell GR, Kaufer D, Hall GF, Lu KP, Ransohoff RM, Cleveland RO, Kowall NW, Stein TD, Lamb BT, Huber BR, Moss WC, Friedman A, Stanton PK, McKee AC, Goldstein LE (2018) Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model. Brain 141:422–458. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx350

Tang J, Erdener SE, Sunil S, Boas DA (2019) Normalized field autocorrelation function-based optical coherence tomography three-dimensional angiography. J Biomed Opt 24:1. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.24.3.036005

Toledo JB, Arnold SE, Raible K, Brettschneider J, Xie SX, Grossman M, Monsell SE, Kukull WA, Trojanowski JQ (2013) Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre. Brain 136:2697–2706. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt188

Uretsky M, Bouix S, Killiany RJ, Tripodis Y, Martin B, Palmisano J, Mian AZ, Buch K, Farris C, Daneshvar DH, Dwyer B, Goldstein L, Katz D, Nowinski C, Cantu R, Kowall N, Huber BR, Stern RA, Alvarez VE, Stein TD, McKee A, Mez J, Alosco ML (2021) Association Between Antemortem FLAIR White Matter Hyperintensities and Neuropathology in Brain Donors Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts. Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000013012.10.1212/WNL.0000000000013012

Veksler R, Vazana U, Serlin Y, Prager O, Ofer J, Shemen N, Fisher AM, Minaeva O, Hua N, Saar-Ashkenazy R, Benou I, Riklin-Raviv T, Parker E, Mumby G, Kamintsky L, Beyea S, Bowen CV, Shelef I, O’Keeffe E, Campbell M, Kaufer D, Goldstein LE, Friedman A (2020) Slow blood-to-brain transport underlies enduring barrier dysfunction in American football players. Brain 143:1826–1842. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa140

Vonsattel JPG, del Amaya MP, Keller CE (2008) Twenty-first century brain banking. Processing brains for research: the Columbia University methods. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 115:509–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-007-0311-9

Wang H, Magnain C, Sakadžić S, Fischl B, Boas DA (2017) Characterizing the optical properties of human brain tissue with high numerical aperture optical coherence tomography. Biomed Opt Express 8:5617. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.8.005617

Weil ZM, Karelina K, Whitehead B, Velazquez-Cruz R, Oliverio R, Pinti M, Nwafor DC, Nicholson S, Fitzgerald JA, Hollander J, Brown CM, Zhang N, DeVries AC (2021) Mild traumatic brain injury increases vulnerability to cerebral ischemia in mice. Exp Neurol 342:113765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113765

Wendel KM, Lee JB, Affeldt BM, Hamer M, Harahap-Carrillo IS, Pardo AC, Obenaus A (2019) Corpus Callosum Vasculature Predicts White Matter Microstructure Abnormalities after Pediatric Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma 36:152–164. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2018.5670

Whitehead B, Velazquez-Cruz R, Albowaidey A, Zhang N, Karelina K, Weil ZM (2022) Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Induces Time- and Sex-Dependent Cerebrovascular Dysfunction and Stroke Vulnerability. J Neurotrauma neu.2022.0335. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2022.0335

Wu Y, Wu H, Zeng J, Pluimer B, Dong S, Xie X, Guo X, Ge T, Liang X, Feng S, Yan Y, Chen J-F, Sta Maria N, Ma Q, Gomez-Pinilla F, Zhao Z (2021) Mild traumatic brain injury induces microvascular injury and accelerates Alzheimer-like pathogenesis in mice. Acta Neuropathol Commun 9:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-021-01178-7

Yun DH, Park Y-G, Cho JH, Kamentsky L, Evans NB, Albanese A, Xie K, Swaney J, Sohn CH, Tian Y, Drummond G, Guan W, DiNapoli N, Choi H, Ruelas L, Feng G, Chung K Ultrafast immunostaining of organ-scale tissues for scalable proteomic phenotyping. 28

Zimmerman KA, Kim J, Karton C, Lochhead L, Sharp DJ, Hoshizaki T, Ghajari M (2021) Player position in American football influences the magnitude of mechanical strains produced in the location of chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology: A computational modelling study. J Biomech 118:110256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110256

Zimmerman KA, Laverse E, Samra R, Yanez Lopez M, Jolly AE, Bourke NJ, Graham NSN, Patel MC, Hardy J, Kemp S, Morris HR, Sharp DJ (2021) White matter abnormalities in active elite adult rugby players. Brain Commun 3:fcab133. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab133

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of resources and facilities at the VA Boston Healthcare System and National Center for PTSD Brain Bank.

Funding

This work was supported by grants NINDS/NIA RF1NS122854, NINDS K23NS102399, NINDS/NIA F31NS127449, United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, BLRD Merit Award (I01BX005933); National Institute of Aging (R01AG075876); National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U54NS115266); National Institute of Aging Boston University AD Research Center (P30AG072978).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GAR, BRH, TDS and ACM assisted with study design. GAR performed the tissue clearing, staining, and imaging. GAR and SH performed image analysis. GAR and YT performed statistical analysis. JDC provided p-tau density measurements. DK stained tissue with Ki67 and imaged it. BRH, ACM, TDS, and VEA conducted neuropathological diagnoses. JM and MLA conducted diagnostic assessments. RN and HK harvested the tissue. MU assisted with obtaining clinical data variables. KD conducted a preliminary case review. RM, KAC, and CAK performed histology. GAR, DK, BRH, and ACM wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Studies were approved by the institutional review board (IRB) through the Boston University Alzheimer's Disease Center (ADC) and CTE Center, Human Subjects Institutional Review Board of the Boston University School of Medicine, and Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital (Bedford, MA).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no duality or competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Causes of death and comorbidities of brain donors.

Additional file 2.

Full data set of clinical, neuropathological, and measured vascular data.

Additional file 3.

Examples of negative Ki67 immunohistochemical staining. Images Ki67 staining and DAPI on cases with a) No CTE or RHI exposure, b) No CTE with RHI exposure, c) Low CTE, and d) High CTE.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosen, G., Kirsch, D., Horowitz, S. et al. Three dimensional evaluation of cerebrovascular density and branching in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. acta neuropathol commun 11, 123 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-023-01612-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-023-01612-y