Abstract

Human WWOX gene resides in the chromosomal common fragile site FRA16D and encodes a tumor suppressor WW domain-containing oxidoreductase. Loss-of-function mutations in both alleles of WWOX gene lead to autosomal recessive abnormalities in pediatric patients from consanguineous families, including microcephaly, cerebellar ataxia with epilepsy, mental retardation, retinal degeneration, developmental delay and early death. Here, we report that targeted disruption of Wwox gene in mice causes neurodevelopmental disorders, encompassing abnormal neuronal differentiation and migration in the brain. Cerebral malformations, such as microcephaly and incomplete separation of the hemispheres by a partial interhemispheric fissure, neuronal disorganization and heterotopia, and defective cerebellar midline fusion are observed in Wwox−/− mice. Degenerative alterations including severe hypomyelination in the central nervous system, optic nerve atrophy, Purkinje cell loss and granular cell apoptosis in the cerebellum, and peripheral nerve demyelination due to Schwann cell apoptosis correspond to reduced amplitudes and a latency prolongation of transcranial motor evoked potentials, motor deficits and gait ataxia in Wwox−/− mice. Wwox gene ablation leads to the occurrence of spontaneous epilepsy and increased susceptibility to pilocarpine- and pentylenetetrazol (PTZ)-induced seizures in preweaning mice. We determined that a significantly increased activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) occurs in Wwox−/− mouse cerebral cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum. Inhibition of GSK3β by lithium ion significantly abolishes the onset of PTZ-induced seizure in Wwox−/− mice. Together, our findings reveal that the neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative deficits in Wwox knockout mice strikingly recapitulate the key features of human neuropathies, and that targeting GSK3β with lithium ion ameliorates epilepsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Common fragile sites are large chromosomal regions that tend to form gaps or breaks under replication stress. Genomic instability and alterations at the chromosomal fragile sites have been implicated as being causative for many types of human cancers [23]. Interestingly, mutations in the genes residing within the common fragile regions, such as the genes encoding PARKIN, GRID2, CNTNAP2, Disabled-1 and LRP1B, have been shown to be associated with neurological disorders, including juvenile parkinsonism, cerebellar ataxia and atrophy, neuronal migration abnormalities during development, epileptic seizures, autism and Alzheimer’s disease [14, 26, 27, 32, 51, 54, 63, 64]. How genomic alterations at common fragile sites lead to neuropathology is largely unclear.

Human WWOX gene is mapped to a common fragile site FRA16D on chromosome 16q23.3–24.1, and encodes a tumor suppressor WW domain-containing oxidoreductase, WWOX [11, 17, 56]. Deletions, loss of heterozygosity and translocations of WWOX gene have been frequently observed in various human malignancies, such as breast, prostate, ovarian, esophageal, lung, stomach, and pancreatic cancers [16, 44]. Downregulation of proapoptotic WWOX expression is associated with cancer progression [7, 37]. Recent studies have suggested that WWOX may act more than a tumor suppressor. Upon neuronal injury, WWOX is activated via phosphorylation at tyrosine 33 and translocates to the mitochondria and nucleus [18, 41]. In a rat model of Parkinson’s disease, treatment of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridinium (MPP+) rapidly increases complex formation of WWOX and JNK1, followed by nuclear accumulation of WWOX and neuronal death in the cortical and striatal neurons [43]. WWOX protein expression is significantly downregulated in the hippocampal neurons of patients with Alzheimer’s disease [59]. Suppression of WWOX expression by small interfering RNA induces Tau hyperphosphorylation and formation of neurofibrillary tangles in neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells, suggesting a crucial role of WWOX in inhibiting Tau phosphorylation in the degenerative neurons of Alzheimer’s disease [15, 58, 59]. Wwox-deficient mice are significantly reduced in size, exhibit abnormalities of bone metabolism and succumb to death by 4 weeks postnatally [8, 9]. In additional to the inhibition of runt-related transcription factor 2 for regulating osteoblast differentiation and bone tissue formation, WWOX also suppresses the transactivation ability of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1α for controlling glucose metabolism and mitochondrial respiration [3, 8]. Although WWOX has been demonstrated to exert its functions through regulating many signaling molecules, the vital requirements for WWOX in vivo remain largely undefined.

During mouse embryonic development, WWOX is highly expressed in the neural crest-derived structures such as cranial and spinal ganglia, skin pigment cells and mesenchyme in the head, suggesting possible involvement of WWOX in neuronal differentiation and maturation [19]. WWOX has been shown to interact with and inhibit glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) for promoting microtubule assembly activity of Tau and neurite outgrowth during retinoic acid-induced SH-SY5Y neuronal differentiation [65]. Of note, similar to a spontaneous lde mutant rat model, the phenotypes of patients with homozygous loss-of-function mutations of WWOX gene from consanguineous families include microcephaly, cerebellar ataxia associated with epileptic seizures and mental retardation, retinopathy, profound developmental delay, and premature death [2, 12, 22, 35, 48, 50, 57, 60, 61]. However, the neurodevelopmental deficits due to functional loss of WWOX remain undefined. In the developing brain, immature neurons migrate outwards from the neuroectoderm to their defined locations, giving rise to characteristic cell layers. Here, we show that targeted disruption of Wwox gene in mice disturbs neuronal migration in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum. Remarkably, our generated Wwox knockout mice recapitulate the key features of human neuropathies, including brain malformations and neuronal degeneration along with epilepsy and motor disorders, making them a valuable disease model in which to delineate the developmental and pathological processes that lead to central and peripheral nerve dysfunction.

Materials and methods

Wwox gene knockout mice, rotarod performance and footprint analysis

Mouse Wwox gene locates on chromosome band 8E1 and consists of nine exons, giving rise to a ~ 2.2 kb transcript. The exon 1 of Wwox contains the 5′-UTR and a start codon for translation of a 46-kDa full-length protein. A previous study has developed a Wwox knockout mouse model by targeting exons 2/3/4 [9]. To test if the possibly generated aberrant protein may cause phenotypes due to the presence of exon 1 in the mouse genome, we generated both exon 1- and exon 2/3/4-targeting knockout mouse strains for comparison (Additional file 1, online resource). Mice were maintained on standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum in a specific pathogen-free environment. The experimental procedures were carried out in strict accordance with approved protocols for animal use from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National Cheng Kung University.

The tests for motor coordination and balance were performed in mice at 18–20 days of age according to the procedures described previously [13]. For rotarod tests, mice were acclimatized to a rotarod (Ugo Basile Model 7650-RotaRod Treadmill) rotating at 5 rpm for 5 min, and a 10-min intertrial interval was allowed in the training period. Four trials per day for three consecutive days were conducted prior to data acquisition. For the constant speed rotarod test, each mouse was placed individually on the rotating rod set at a fixed speed, and the latency to fall off the rotating rod was measured. For the accelerating rotarod test, the assessment began at 4 rpm and gradually increased to a maximum speed of 40 rpm over a period of 5 min. If the mouse stayed on the rod till the end of 10-min trial, a time of 600 s was recorded. Mice were given two trials each day for five consecutive days. The mean values were used for statistical comparison.

For footprint analysis, mouse forepaws were dipped in nontoxic water-based red ink, and hind paws in blue. The mice were then allowed to walk along an enclosed runway and leave a set of footprints on white paper. The stride length, base width and the hind/fore-base ratio were measured for mouse gait analysis. At least five steps were measured for each mouse, and the mean of values was used for analysis.

Recording of transcranial motor evoked potentials (Tc-MEPs)

Mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized with chloral hydrate in PBS (400 mg/kg; Tokyo Chemical Industry, product no. C0073). The depth of anesthesia was monitored by withdrawal reflex upon tail pinch. Core temperature was monitored using a rectal probe connected to a multichannel thermometer (Portable Hybrid Recorder, model 3087; Yokogawa Hokushin Electric, Tokyo, Japan) and maintained at 37 °C by heating pads and lamp. Tc-MEPs were recorded using monopolar myographic needle electrodes placed in the intrinsic plantar muscles of bilateral forelimbs. A ground electrode was placed subcutaneously between the stimulating and the recording sites. The stimulus was applied with a duration of 0.2 msec in a series of square pulses using two needle electrodes attached to the scalp. The presentation rate of stimulation was 1/s. The supramaximal stimulus was assessed and the recording was performed at an intensity of 10% above the stimulus level that produced maximal amplitudes. The recording time was 10 msec, and the recorded signals were amplified and filtered between 1 and 2000 Hz. At least three sequential single-sweep runs (i.e., without averaging) with similar waveforms were recorded to verify the consistency of responses. The electrophysiological data were collected, processed and analyzed on a Neuropack Z recording device (Nihon Koden, Tokyo, Japan). Amplitude of the Tc-MEPs was defined as the peak-to-peak distance in microvolts (μV), and latency of the response was measured from the onset of electrical shock artifact to the major positive peak in msec.

Immunoelectron microscopy, luxol fast blue (LFB) and cresyl violet staining, immunohistochemistry and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

Mouse sciatic nerves were fixed in 4% glutaraldehyde/0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2), dehydrated and embedded in EMbed 812 resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in a 60 °C oven. Semi-thin transverse sciatic nerve sections (800 nm; Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome) were stained with 1% toluidine blue/1% azure/1% sodium borate in H2O for 30 s, and examined under a light microscopy (Olympus BX51). For electron microscopy, ultrathin sections (90 nm) were prepared, incubated with rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) antibody (Cell Signaling), and then stained with 20-nm gold particle-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (BB International Ltd). The samples were further stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 20 min and 4% lead citrate for 3 min, and examined under a transmission electron microscopy (Hitachi H-7000).

Mouse brains or embryos were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS and embedded in paraffin. Five-μm tissue sections on glass slides were deparaffinized, hydrated through serial concentrations of ethanol and finally in distilled water. The brain sections were incubated in 0.1% LFB/0.5% acetic acid/95% ethanol solution at 56 °C overnight, rinsed in 95% ethanol and then distilled water, and differentiated in 0.05% lithium carbonate solution for 30 s. The samples were counterstained in 0.1% cresyl violet solution for 6 min, dehydrated in 95% and absolute ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted. Immunohistochemistry of the 5-μm tissue sections was performed as described previously [37], using specific antibodies against doublecortin (DCX) (1:40, Santa Cruz and GeneTex), NeuN (1:2000 dilution, Millipore), calbindin (1:500, Sigma) and Ki67 (1:150, Dako) in Dako diluent. After incubating with a secondary antibody and NovoLink polymer (Leica Biosystems), the tissue sections were treated with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) substrate chromogen (Zymed), counterstained with hematoxylin solution, and mounted in aqueous mounting media.

For TUNEL assay, an ApopTag plus peroxidase in situ apoptosis detection kit (Millipore) was used to analyze DNA fragmentation in cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, deparaffinized brain sections were rehydrated, incubated with proteinase K (20 μg/ml) at room temperature for 15 min, and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 10 min to quench the endogenous peroxidase activity. After equilibration, the samples were incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase in reaction buffer containing digoxigenin-conjugated nucleotides at 37 °C for 1 h to label the free DNA termini. The incorporated nucleotides within the fragmented DNA were detected by the binding of peroxdase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody, followed by the addition of AEC substrate chromogen. The tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin solution for 10 min at room temperature, and TUNEL-positive cells were visualized under an Olympus BX51 microscope.

Western blotting

Cerebellum, hippocampus and cerebral cortex tissues were isolated from three genotypes of mice at postnatal day 14 for protein extraction using a lysis buffer containing 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Tween 20, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 10 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and 1:20 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) in PBS. Western blot analysis was performed as described previously [62], using anti-WWOX, anti-DCX (GeneTex), and anti-β-actin (Sigma) antibodies.

Induction of seizure

Methylscopolamine bromide, pilocarpine, pentylenetetrazol (PTZ), ethosuximide and lithium chloride (LiCl) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride freshly before use. For pilocarpine-induced seizure model, the mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) pretreated with methylscopolamine bromide (1 mg/kg) 30 min prior to pilocarpine administration to limit peripheral cholinergic effects, and then injected with pilocarpine (i.p., 50 mg/kg). After methylscopolamine pretreatment, the control mice were given an equal volume of saline. For PTZ model, we injected PTZ i.p. to mice at a dose of 30 mg/kg [46]. Following pilocarpine or PTZ injection into the mice, the seizure severity was assessed for 60 min according to a modified version of Racine scale: stage 0, no response; stage 1, behavioral arrest followed by vibrissae twitching; stage 2, head nodding; stage 3, unilateral forelimb clonus and myoclonic jerk; stage 4, bilateral forelimb clonus with rearing; stage 5, generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) and loss of righting reflex; stage 6, dead [55]. Ethosuximide (i.p., 150 mg/kg), a T-type Ca2+ channel blocker that has anticonvulsant activity (Luszczki et al., 2005), was injected into mice 45 min before PTZ-induced clonic seizures. LiCl (i.p., 60 mg/kg) were pretreated three times within 1 h before PTZ injection.

Statistical analysis

We performed statistical tests with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the difference among groups. The differences were considered significant when the P values were less than 0.05. All results are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Neurological motor disorders in Wwox gene knockout mice

We have developed two knockout mouse models with ablation of exon 1 or exons 2/3/4 of Wwox gene (WD1 or WD234 henceforth, respectively). Southern blot analysis using genomic DNA isolated from mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and polymerase chain reactions using mouse tail DNA demonstrated that Wwox gene was disrupted in both WD1 and WD234 mice (Additional file 1: Figure S1a, b). There was undetectable protein expression in the homozygous Wwox knockout (Wwox−/−) MEF (Additional file 1: Figure S1c). In agreement with a previous study [8], our generated Wwox−/− mice with exon 1- or exon 2/3/4-deletion showed severe dwarfism and survived for less than a month (Additional file 1: Figure S1d).

High expression levels of WWOX protein have been observed in the neural crest-derived structures such as cranial and spinal ganglia, skin pigment cells and mesenchyme in the head of mouse embryo, suggesting possible involvement of WWOX in neuronal differentiation [19]. Compared with the Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− littermates, reduction in brain size and weight was observed in Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 20 (Additional file 1: Figure S1e and S1f for WD1, respectively, and data not shown for WD234). As in Wwox knockout mouse models, a homozygous WWOX nonsense mutation caused growth retardation, microcephaly and early death in a patient from a consanguineous family [2]. No differences in brain water contents were detected among the mice of three genotypes (Additional file 1: Figure S1 g). To assess the role of WWOX in neuronal functions, Wwox−/− mice were first examined for their motor coordination phenotypes. Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice exhibited a normal plantar reaction when they were suspended by their tails, whereas Wwox−/− mice showed abnormal hind limb-clasping reflexes (Fig. 1a). In rotarod tests, Wwox−/− mice had much shorter latency periods before falling off the rotating rotarod at either constant or accelerating speeds than their Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− littermates (Fig. 1b, c). Moreover, a footprint assay was performed to record gait abnormalities in Wwox deficient mice. Wwox−/− mice showed uncoordinated movements and overlapped footprints of their fore and hind paws (Fig. 1d). Our data showed that the stride length, hind-base width, and hind-to-fore base ratio were significantly decreased in Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 1d, e). Similar results were obtained when analyzing the ratio of stride length or hind-base width to the body size (data not shown). There were no significant differences between Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice (Fig. 1b-e). We performed rotarod tests and footprint assay with both WD1 and WD234 mice and obtained similar results (Fig. 1b-e). Our results indicate that Wwox gene ablation in mice leads to gait ataxia and severe impairment in their motor coordination, grip strength and balance.

Wwox−/− mice exhibit motor disorders. a Tail suspension test revealed abnormal limb-clasping reflex in Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 20. b, c Rotarod analysis of motor function in three genotypes of both WD1 and WD234 mice was performed on a constant-speed (b) or accelerating rotarod (c). The latencies from rotation onset until the mice fell off the rod were recorded. Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice managed to stay significantly longer on the rotarod than Wwox−/− mice. d, e Footprint analysis of gait abnormalities in Wwox−/− mice. Mouse forepaws were marked with red ink and hind paws with blue for gait assessment. The mice with ink on their paws were trained to run down a corridor and the mouse gait patters of three genotypes were obtained (d). The stride length and hind-base width of Wwox−/− mice were significantly shorter than those of Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice (e). Also, the hind to fore-base ratios were lower in Wwox−/− mice compared with their littermates (e). Differences between Wwox−/− versus Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− littermates were statistically significant in a one-way ANOVA test. Each result represents the average of data obtained and error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM). n.s., non-significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; RPM, revolutions per minute; N, number of animals tested

Nerve degeneration and demyelination in Wwox −/− mice

Motor neuropathies may lead to defects in movement coordination. To understand whether Wwox deficit leads to abnormalities in the functional state of motor nervous system, Tc-MEPs were recorded in three genotypes of mice at 3 weeks of age. The Tc-MEPs elicited by electrical stimulation of the motor cortex monitor the descending response that is propagated through the corticospinal tracts to cause a muscle contraction. Compared with the results recorded in Wwox+/+ mice (59.2 ± 9.0 μV; n = 10), a significant reduction in the amplitudes of Tc-MEPs with an average of 11.8 ± 5.4 μV was analyzed in Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 2a, b; n = 4, p < 0.05). The onset latency of Tc-MEP showed a significant prolongation in Wwox−/− (2.44 ± 0.37 msec) than Wwox+/+ mice (1.39 ± 0.13 msec) (Fig. 2c; p < 0.01). Although the mean amplitude of Tc-MEP recoded in Wwox+/− mice (59.6 ± 17.2 μV; n = 5) was comparable to Wwox+/+ mice, an increase in Tc-MEP latency was determined in Wwox+/− mice (2.13 ± 0.22 msec; p < 0.05) when compared with the wild-type mice (Fig. 2b, c), suggesting that Wwox haploinsufficiency may cause a partial Tc-MEP deteriorative change in mice.

Wwox knockout in mice leads to the changes in Tc-MEPs. a Representative bilateral Tc-MEPs detected in wild-type control and Wwox knockout mice. When compared to Wwox+/+ mice, significantly reduced amplitudes (b) and increased latencies of Tc-MEPs (c) were determined in Wwox−/− mice at 3 weeks of age. A statistically significant increase in the Tc-MEP latency, but no changes in amplitude, was observed in Wwox+/− mice, indicating that haploinsufficiency of Wwox gene may cause a delay in wave latencies with no effect on their amplitudes. The results are expressed as means ± SEM. n.s., non-significant. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

We then assessed whether the alterations in neurophysiological function were supported by the presence of neuropathological changes in Wwox−/− mice. Semi-thin transverse sciatic nerve sections stained with toluidine blue revealed similar axonal organization and approximately equal numbers of nerve fibers in wild-type and Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 3a). However, smaller endoneurium spaces were observed in Wwox−/− mouse sciatic nerves (Fig. 3a, b). Strikingly, a large number of abnormal-shaped and demyelinated axons in a compact mass were found in the sciatic nerves of Wwox−/− mice by transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 3b). Detachment of myelin lamellae and loss of axoplasm were evident in the degenerative sciatic nerve fibers of Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 3b). Myelin thickness, axonal organization and the density of myelinated fibers were similar in Wwox+/− and Wwox+/+ mice (data not shown). Schwann cells produce the myelin sheath around axons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). A cleaved form of active caspase-3 was detected in the Schwann cells of Wwox−/− mice by immunoelectron microscopy (Fig. 3c), indicating that Wwox deficit may cause Schwann cell apoptosis and axon demyelination in the PNS.

Peripheral nerve degeneration and Schwann cell apoptosis in Wwox−/− mice. a Semi-thin toluidine blue-stained transverse sections of sciatic nerves embedded in EMbed 812 resin from Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 20 are shown (N = 3). Scale bars = 50 μm. b Electron microscopy revealed normal ultrastructural features of axons (Ax), myelin sheath (My) and endoneurium (En) in EMbed 812 resin-embedded sciatic nerve sections from Wwox+/+ mice. In contrast, abnormal-shaped nerve fibers (red stars), axon demyelination (blue arrow) and onion bulb degeneration (red arrowheads) were observed in all Wwox−/− sciatic nerves examined in this study (N = 3). Red arrows indicate detachment of myelin lamellae with invasion towards the axolemma due to loss of axoplasm in Wwox−/− axons. A significant reduction in endoneurium spaces was evident in Wwox−/− sciatic nerves. Scale bars = 5 μm. c By immunogold-labelling, cleaved caspase-3 was detected in the Schwann cell (Sc) from Wwox−/− sciatic nerve, photographed at 50,000X magnification. The representative images of three independent experiments are shown

Brain magnetic resonance imaging has revealed poor myelination and progressive atrophy of periventricular white matter resulting in hypoplastic corpus callosum in patients with homozygous mutation in WWOX gene [2, 22, 50, 60]. LFB staining of myelin was performed to examine the white matter fiber tracts in Wwox−/− mouse brain. Compared to the wild-type with regular myelination, Wwox−/− mouse brain sections showed significantly reduced myelin staining intensity in the commissural fibers (corpus callosum, and anterior and dorsal hippocampal commissures), the association fibers (cingulum), and the projection fibers emanating from corpus callosum toward striatum (Fig. 4a-d). The commissural fibers communicate between two cerebral hemispheres and the association fibers connect regions within the same hemisphere of the brain. Myelin pallor was also observed in Wwox−/− internal capsule, where both ascending and descending axons going to and coming from the cerebral cortex pass through (Fig. 4c, d). Of note, hypomyelination with atrophy of optic tract and cerebellar foliar white matter was examined in Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 4c3, d3, e, f). Together, our results provide clear neuropathological findings indicating that severe hypomyelination in the PNS and brain of Wwox−/− mice.

Wwox loss results in severe CNS hypomyelination in mice. a-d LFB staining of CNS white matter fiber tracks using mouse forebrain coronal sections showed that the myelinated neurons were largely reduced in the commissural fibers (corpus callosum, anterior commissures and dorsal hippocampal commissures), association fibers (cingulum; black arrows) and projection fibers (black arrowheads) of all Wwox−/− mice examined at 3 week of age. The enlarged images (a1, b1, c1–3, and d1–3) are from the boxed areas in the upper panel (a-d). Myelin pallor was also observed in the internal capsule (c and d), degenerated optic tract (c3 and d3; red arrowheads) and cerebellar foliar white matter (e and f) of Wwox−/− mice by LFB staining. Nissl staining of neuronal cell bodies was used for counterstaining. The representative results of three independent experiments are shown

Cerebellar hypoplasia with a defective vermis-midline fusion in Wwox −/− mice

Cerebellar modulation and coordination of neuromuscular activities are important in skilled voluntary movement and equilibrium. Cerebellar foliation along the anterior-posterior axis of the vermis during development contributes to increased surface area, permitting the cerebellum to accommodate more cells and facilitating the establishment of more sophisticated sensory-motor circuits. In Wwox−/− mice, an aberrant cerebellum with fusion of vermian lobules VI and VII was observed (Fig. 5a). Histological examination was performed to evaluate developmental changes in the cerebellum of Wwox−/− mice. Midline sagittal cresyl violet-stained section revealed foliation defects in lobules V, VI and VII of Wwox−/− cerebellum (Fig. 5b). Technologically, fusion of vermian lobules VI and VII and a smaller lobule V were observed at postnatal day 19~20 in Wwox−/− cerebellum (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, staining results of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (Fig. 5c, d) and immunofluorescence using an antibody against calbindin, a selective marker for Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (Additional file 1: Figure S2), demonstrated partial loss of the Purkinje cells and their diminished expression of calbindin in Wwox−/− cerebellum at postnatal day 20. TUNEL assay showed increased apoptotic cells in the adjacent granular layer of Wwox−/− cerebellum (Fig. 5e and Additional file 1: Figure S3). Together, aberrant foliation, Purkinje cell loss and neuronal apoptosis in the cerebellum may contribute to early postnatal ataxia in Wwox−/− mice.

Foliation defect, Purkinje cell loss and neuronal apoptosis in the cerebellum of Wwox−/− mice. a Representative images of Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− brains revealed that interhemispheric fissure (arrowheads) and cerebellar vermian lobules VI and VII (arrow) were fused in Wwox−/− brain. b Midline sagittal sections of Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− cerebellum tissues were stained with cresyl violet. A smaller lobule V and fusion of VI with VII were observed in Wwox−/− mouse cerebellum. Scale bars = 500 μm. c H&E staining of the cerebellar cortex tissue sections from Wwox−/− mice (N = 6) showed partial loss of Purkinje cells (arrows) at postnatal day 20. The lower panel pictures are the magnified images from the boxed area in the upper panel. Scale bars = 200 (upper) or 50 μm (lower). d The numbers of Purkinje cells in ten representative subareas of Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− cerebellar cortex tissue sections were quantified. The results are expressed as means ± SEM. **P < 0.01. e Apoptotic cell death was detected in the granular cells of Wwox−/− cerebellum at postnatal day 20 by TUNEL assay. The representative results of four independent experiments are shown. PC, Purkinje cell; GL, Granule cell layer; ML, molecular layer. Scale bars = 200 μm

Wwox is required for proper neuronal migration and development

The homozygous Wwox knockout mice were found along a spectrum of phenotypic severity, and some very severely affected embryos died embryonically. Gross morphological abnormalities could be observed in Wwox−/− mouse brains from live births, ranging from microcephaly to holoprosencephaly, in which the forebrain did not properly divide into two hemispheres during embryonic development. Technically, middle interhemispheric fusion of the posterior frontal and parietal lobes was found in Wwox−/− mouse brains (Fig. 5a and Additional file 1: Figure S4). Given the striking brain morphological phenotypes in Wwox−/− mice, we investigated the function of WWOX during neural development. Wwox−/− mouse embryos at E12.5 were smaller in size and exhibited a growth delay as compared with the wild-type littermates (Additional file 1: Figure S5a). An elongated roof plate and dorsal spinal cord malformation were evident in E12.5 Wwox null embryos (Additional file 1: Figure S5a). In the developing brain, Ki-67+ proliferating cells were decreased in Wwox−/− neocortical subventricular zone and cerebellum compared with the wild-types at E16.5 (Additional file 1: Figure S5b). We found that the overall cortical thickness was significantly reduced in Wwox knockouts at E16.5, in agreement with the reduced neurogenesis (Additional file 1: Figure S5c).

During murine neocortical development, neural progenitor cells (NPCs) undergo proliferation in the ventricular and subventricular zones (VZ and SVZ, respectively) between E11.5 and E16.5 to generate different projection neuron subtypes, and the proliferative activity of NPCs declines after E16.5 [24]. The newly born neurons henceforth exit the cell cycle and migrate to the outer zone of neocortex to develop into mature neurons. Following a pulse of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) to pregnant dams for labeling the actively proliferating cells in embryos at E16.5, our results showed that most BrdU+ neurons born shortly after E16.5 have migrated from the VZ and SVZ to the cortical plate (CP) of Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− neocortex at birth (Additional file 1: Figure S6a). In comparison with their littermates, increased BrdU+ neurons were found throughout the neocortex of Wwox−/− newborn mice, with a large proportion of the nascent neurons still residing in the VZ and SVZ (Additional file 1: Figure S6a). More Ki-67+ proliferating neurons were also observed in the VZ and SVZ of Wwox−/− neocortex at birth (Additional file 1: Figure S6b). These results suggest that Wwox−/− neurons that still have high proliferative activity after E16.5 may be in a less differentiated state and have poor mobility during neocortical development.

To further verify whether the neuronal development in Wwox−/− mice lags behind the wild-type littermates, the expression of DCX protein, an early differentiation marker expressed by NPCs and immature neurons, was examined in these mice. The DCX expression starts to decline as the precursor cells differentiate into mature neurons. Compared with the DCX protein levels in Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice, our results showed that DCX was still highly expressed in Wwox−/− brain tissues at postnatal day 14 (Fig. 6a, b and Additional file 1: Figure S7). During neurogenesis, DCX protein downregulation in the developing neurons is followed by the expression of a mature neuronal marker NeuN. In comparison with the neurons in the dentate gyrus of wild-type hippocampus that strongly expressed NeuN, many cells in the dentate gyrus of Wwox−/− mice showed absent expression of NeuN at postnatal day 20 (Fig. 6c). Moreover, the neuronal cells in the CA1 region of Wwox−/− hippocampus were abnormally dispersed (Fig. 6c). Disorganization of neuronal cells in the dentate gyrus was also observed in the cresyl violet-stained brain section of Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 6d). Neuronal heterotopia (ectopic neurons) could be found in Wwox−/− mouse brain cortex (Additional file 1: Figure S8). Neuronal cell apoptosis was observed in the brain tissues of Wwox−/− mice (Additional file 1: Figure S9). Together, in agreement with a recent study using a human neural progenitor cell culture system [34], our results indicate that loss of Wwox causes disorders in neuronal migration and development and brain malformations in mice.

Defective CNS development in Wwox knockout mice. a Cerebellum, hippocampus and cerebral cortex protein samples from Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 14 or 20 were examined for the expression levels of an early neuronal differentiation marker DCX by western blotting. β-actin was used as an internal control. Quantitative densitometry of the immunoblots was performed and the numbers depict the ratio of DCX to β-actin protein level in the brain tissues. b Immunohistochemistry was performed to determined DCX expression in the cerebral cortex of Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 14 (N = 5). Scale bars = 50 μm. The numbers of DCX-positive cells in five representative subareas of Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− cerebral cortex tissue sections were quantified (right panel). The results are expressed as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05. c Sagittal brain sections of Wwox+/+ and Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 20 were immunostained with anti-NeuN. Compared with the age-matched control littermates, a large proportion of neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) of Wwox−/− mice showed absent expression of a mature neuronal marker NeuN (black star). Dispersed distribution of NeuN-positive neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region of Wwox−/− brain was observed (black arrow). The lower panel pictures of dentate gyrus and CA1 regions are the magnified images from the boxed area in the upper panel. The representative images of six independent experiments are shown. Scale bars = 200 (upper) or 100 μm (lower). DG, dentate gyrus. d Cresyl violet staining of sagittal brain sections revealed a decreased cell density in the subgranule zone (yellow arrow) and a less orderly arrangement of granule neurons (yellow arrowhead) in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 20. The right panel pictures are the magnified images from the boxed area in the left panel. The representative images of five independent experiments are shown. Scale bars = 50 (left) or 20 μm (right)

GSK-3β inhibition ameliorates the hypersusceptibility to epileptic seizure due to Wwox loss in mice

Abnormally migrated neurons form reorganized neuronal networks that create hyperexcitable tissue in the brain and exhibit altered cellular physiologies. Neuronal migration abnormalities during development and heterotopia have been suggested to be associated with increased neuronal excitability, epilepsy and mild to moderate mental retardation in humans and mice [25, 49, 54]. Similar to the spontaneous Wwox mutation in lde/lde rats, a patient with a homozygous WWOX nonsense mutation has been reported to display a phenotype of growth retardation, microcephaly, epilepsy, retinal degeneration and early death [2, 57]. In our generated Wwox−/− mice, spontaneous epileptic seizures were commonly observed after postnatal day 12. Seizures were frequently induced by mild stressors including noise, strobe lights and novel cage during routine handling (Additional file 2: Movie S1).

Additional file 2: Video of spontaneous epileptic seizure.

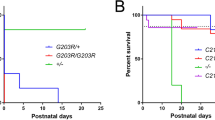

To further investigate the enhanced epileptogenesis in Wwox−/− mice, we tested convulsant agent-induced seizure models using a muscarinic receptor agonist pilocarpine and a GABAergic receptor antogonist PTZ. After intraperitoneal injection of pilocarpine (50 mg kg− 1) or PTZ (30 mg kg− 1), seizure severity was monitored according to the Racine’s scale [55]. Compared with the Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− littermates, we found that Wwox−/− mice showed enhanced susceptibilities to the stimulation of either pilocarpine (Fig. 7a) or PTZ (Fig. 7b), and developed to a series of generalized tonic-clonic seizures immediately after injection. Half of the pilocarpine- or PTZ-injected Wwox−/− mice evolved into status epilepticus (SE, defined as three or more tonic-clonic seizures during 1-h observation). SE was not observed in Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice. Pretreatment of an antiepileptic drug ethosuximide suppressed PTZ-induced seizure in Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 7b), although ethosuximide pretreatment had no effects on the behavior changes in Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice treated with a low dose of PTZ.

Increased GSK3β activity in the brain tissues leads to hypersusceptibility to drug-induced seizure in Wwox knockout mice. a Wwox−/− mice showed increased susceptibility to seizure induction by the injection of pilocarpine (50 mg/kg), a muscarinic receptor agonist. Behavioral scoring of seizure severity according to the Racine’s scale [55] in three genotypes of mice for 60 min is presented. b Higher seizure activity was observed in Wwox−/− mice after injection of PTZ (30 mg/kg), a GABAergic receptor antagonist, as compared with Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mice. Pretreatment of ethosuximide (ETS, 150 mg/kg) suppressed PTZ-induced seizure activity in Wwox−/− mice. c Increased activation of GSK3β was determined in the cerebellum, hippocampus and cerebral cortex of Wwox−/− mice at postnatal day 20, as evidenced by dephosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9. β-actin was used as an internal control in western blotting. Quantitative densitometry of the immunoblots was performed, and the numbers depict the ratio of phosphorylated or total GSK3β to β-actin protein level in the brain tissues. The representative results of four independent experiments are shown. d Pretreatment of a GSK3β inhibitor LiCl (60 mg/kg) suppressed PTZ-induced seizure activity in Wwox−/− mice. The results are expressed as means ± SEM. n.s., non-significant. ***P < 0.001

WWOX has been shown to interact with and inhibit GSK3β, thereby increasing the microtubule assembly activity of Tau and promoting neurite outgrowth in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells [65]. To investigate whether the enhanced epileptogenesis in Wwox−/− mice is due to increased GSK3β activation in neuronal cells, we determined dephosphorylation of GSK3β at Ser9 (active GSK3β) in Wwox−/− mouse cerebellum, hippocampus and brain cortex by western blotting (Fig. 7c). Injection of a potent GSK3β inhibitor lithium chloride significantly suppressed PTZ-induced epileptic seizure in Wwox−/− mice (Fig. 7d). Together, these results suggest an important role of GSK3β in the hypersusceptibility to epileptic seizure induction due to Wwox loss in neuronal cells.

Discussion

In spite of its putative function as a tumor suppressor, Wwox expresses abundantly in mouse developing nervous system [19]. In this study, we applied a mouse genetics approach and demonstrated that Wwox deficiency in mice leads to neurodevelopmental deficits and neurodegeneration that resemble human neuropathologic features. First, severe hypomyelination with atrophy of optic tract and white matter fiber tracts in Wwox−/− mouse brain recapitulates the clinical findings in patients with homozygous mutations in WWOX gene. Of note, our electron microscope images revealed Schwann cell apoptosis and axon demyelination and degeneration in Wwox−/− sciatic nerves. Since normal conductance of nerve impulses depends on the insulating properties of myelin sheath surrounding the nerve fiber, severe hypomyelination in the central and peripheral nervous systems may cause the behavioral deficits including poor balance, motor incoordination and gait ataxia in Wwox−/− mice. Myelin is composed of lipid-rich substance generated by oligodendrocytes in central nervous system (CNS) and by Schwann cells in PNS. The major protein content of CNS myelin includes myelin basic protein (MBP), myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) and proteolipid protein (PLP). MOG is unique to the CNS myelin. In addition to MBP and MAG, the PNS myelin contains abundant myelin protein zero (MPZ) that is absent in the CNS and is involved in holding together the multiple concentric layers of PNS myelin sheath. A recent study has reported a significantly decreased number of mature oligodendrocytes and reduced MBP expression in the cerebral cortex of lde rats with spontaneous Wwox mutation [61]. Mutations in the myelin proteins, such as PLP and MPZ, are associated with the neuropathic disorders in patients with Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, respectively [40]. Inflammatory responses against MBP, MOG and MAG are known to cause demyelinating diseases. Whether Wwox deficiency leads to myelin protein deficits or neurodegenerative autoimmune diseases is unknown. Moreover, WWOX has been suggested to be associated with lipid metabolism [4, 31, 36, 39]. Whether WWOX regulates myelin formation via controlling lipid biosynthesis and metabolism and supports cell survival in oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells needs further investigation.

Second, we show here that Wwox deficiency in mice leads to marked foliation defects and loss of Purkinje cells along with granular cell apoptosis in the cerebellum (Fig. 5). Cerebellar hypoplasia and aberrant foliations in vermian lobules VI and VII have been shown to be associated with defective Wnt/β-catenin signaling in a mouse model of loss of function of Ahi1, a Joubert syndrome-associated gene [38]. Joubert syndrome is an autosomal recessive neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by agenesis of cerebellar vermis, neonatal hypotonia, ataxia, developmental delay, and cognitive disabilities including autism and mental retardation. Smad2 depletion in mice also caused cerebellar foliation anomalies and ataxia [66]. WWOX has been suggested to regulate β-catenin and Smad-driven promoter activities in Wnt and TGF-β signaling, respectively [5, 28, 29]. Because the survival of cerebellar granular cells largely depends on their synaptic connection with Purkinje cells [45], whether WWOX prevents Purkinje cell degeneration, thereby supporting granular cell growth during cerebellar development via regulating Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β/Smad2 signaling pathways remains to be determined.

Cerebellar ontogenesis is regulated by lipophilic hormones, including thyroid hormone and sex steroids [6, 21, 33]. In perinatal hypothyroidism, the growth and branching of Purkinje cell dendrites are greatly reduced. Thyroid hormone deficiency also causes delayed migration of granular cells to the internal granular cell layer and defective synaptic connection within the cerebellar cortex [33]. WWOX has been shown to be highly expressed in the secretory epithelial cells of hormonally regulated organs including breast, ovary, testis and prostate, and targeted deletion of Wwox in mouse mammary gland leads to impaired mammary ductal development [1, 53]. WWOX expression is relatively strong in human, rat and mouse neural tissues, and varies according to the location [19, 34, 53, 61]. Notably, WWOX may interact with steroid hormone 17β-estradiol via its NSYK (Asn-Ser-Tyr-Lys) motif in the C-terminal short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase/reductase domain for neuroprotection [42]. Whether WWOX acts as a receptor for steroid hormones for initiating neuroprotective signaling pathways and promoting cerebellum development is unclear. The functional role of Wwox in a particular cell type needs to be further analyzed using conditional tissue-specific knockout mouse models.

Third, we identify a crucial role of WWOX in neurogenesis and neocortical development. Mammalian CNS development is achieved by proliferation of NPCs followed by their transition from a proliferative state to differentiation. In the developing cerebral cortex, NPCs exit the cell cycle in the VZ and SVZ, whereafter the postmitotic neurons migrate towards the outer zone of neocortex to form laminated cortical layers. At birth, a large number of the postmitotic neurons born around E16.5 have migrated to the CP and developed into mature neurons in Wwox+/+ and Wwox+/− mouse neocortex, whereas the Wwox−/− neocortical neurons display aberrant progenitor proliferation and migration and are less differentiated. Our findings raise some new questions. For instance, it is unclear whether the deficits in neuronal migration and differentiation are associated with the aberrant proliferation of Wwox−/− neocortical progenitor neurons. Also, whether WWOX regulates the switch from progenitor proliferation to migration in the developing brain is unknown.

The development of mammalian cerebral cortex and hippocampus involves neuronal proliferation, migration, and synaptic refinement within the neuronal circuitry. Neuronal migration deficits during development may lead to malformations of cerebral neocortex and hippocampus that greatly increase neuronal excitability and the risk of seizures [49, 52]. Wwox−/− mice exhibit cerebral malformations consisting of middle interhemispheric fusion, cortical heterotopia and neuronal disorganization in the hippocampal CA1 region and display increased susceptibilities to convulsant-induced seizures. The aberrant positioning of neurons in Wwox−/− neocortex and hippocampus may cause reorganization of neuronal networks and alteration of cellular physiology that create hyperexcitable tissue. Foci of aberrantly migrated neurons and cortical dysplasias have been known to be associated with pharmacologically intractable epilepsies. Administration of GSK3β inhibitor lithium chloride effectively ameliorated the seizure susceptibility in Wwox−/− mice, and its efficacy is better than the commonly used anticonvulsant drug ethosuximide. Lithium is a widely used mood stabilizer in the treatment of bipolar and depressive disorders. Administration of lithium in mice has been demonstrated to attenuate PTZ-induced clonic seizure [10], and rescue Wnt-dependent cerebellar midline fusion and neurogenesis deficits early in development [38]. Lithium treatment has also been shown to induce β-catenin-mediated myelin gene expression in mouse Schwann cells and enhance remyelination of the injured peripheral nerves in mice [47]. GSK3β signaling plays key roles in the regulation of neurogenesis, neuronal polarization and axon growth during neural development [30]. WWOX interacts with GSK3β and suppresses GSK3β-mediated Tau phosphorylation for promoting retinoic acid-induced microtubule assembly activity of Tau and neurite outgrowth in SH-SY5Y cells [65]. WWOX also binds to Tau via its C-terminal short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase/reductase domain for preventing Tau hyperphosphorylation and neurofibrillary tangle formation [59]. Without WWOX, protein aggregation cascade starting from TRAPPC6AΔ, TIAF1 and SH3GLB2 may cause APP degradation and aggregation of amyloid β and Tau in neurons [15, 20]. Downregulation of WWOX protein expression has been observed in the hippocampal neurons in patients with Alzheimer’s disease [59]. Future experiments can now be directed at determining the regulation of GSK3β activity by WWOX in neural development and neurodegeneration. Whether lithium treatment can rescue the deficits in neuronal migration and differentiation during development in Wwox−/− mice remains to be studied.

In summary, Wwox gene ablation causes severe neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders and convulsive seizures in mice. Most importantly, Wwox knockout mouse models recapitulate the key pathological features of human neuropathies and can be considered a valuable research tool for delineation of molecular pathogenesis and development of therapeutic strategies for refractory epilepsy. Future studies, as well as more evaluations, will be needed to test whether GSK3β inhibitors may be promising candidates for treatment of human neurological disorders due to loss or dysfunction of WWOX.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed in this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AEC:

-

3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- Ax:

-

Axons

- BrdU:

-

Bromodeoxyuridine

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CP:

-

Cortical plate

- DCX:

-

Doublecortin

- DG:

-

Dentate gyrus

- En:

-

Endoneurium

- ETS:

-

Ethosuximide

- GSK3β:

-

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- GTCS:

-

Generalized tonic-clonic seizure

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

- i.p.:

-

Intraperitoneally

- LFB:

-

Luxol fast blue

- LiCl:

-

Lithium chloride

- MAG:

-

Myelin-associated glycoprotein

- MBP:

-

Myelin basic protein

- MEF:

-

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- MOG:

-

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MPP+ :

-

1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridinium

- MPZ:

-

Myelin protein zero

- My:

-

Myelin sheath

- NPCs:

-

Neural progenitor cells

- NSYK:

-

Asn-Ser-Tyr-Lys

- PLP:

-

Proteolipid protein

- PNS:

-

Peripheral nervous system

- PTZ:

-

Pentylenetetrazol

- Sc:

-

Schwann cell

- SE:

-

Status epilepticus

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- SVZ:

-

Subventricular zones

- Tc-MEPs:

-

Transcranial motor evoked potentials

- TUNEL:

-

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- VZ:

-

Ventricular zones

- WD1:

-

Wwox gene exon-1 deletion

- WD234:

-

Wwox gene exon-2/3/4 deletion

- WWOX:

-

WW domain-containing oxidoreductase

References

Abdeen SK, Salah Z, Khawaled S, Aqeilan RI (2013) Characterization of WWOX inactivation in murine mammary gland development. J Cell Physiol 228:1391–1396

Abdel-Salam G, Thoenes M, Afifi HH, Körber F, Swan D, Bolz HJ (2014) The supposed tumor suppressor gene WWOX is mutated in an early lethal microcephaly syndrome with epilepsy, growth retardation and retinal degeneration. Orphanet J Rare Dis 9:12

Abu-Remaileh M, Aqeilan RI (2014) Tumor suppressor WWOX regulates glucose metabolism via HIF1α modulation. Cell Death Differ 21:1805–1814

Abu-Remaileh M, Aqeilan RI (2015) The tumor suppressor WW domain-containing oxidoreductase modulates cell metabolism. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 240:345–350

Aldaz CM, Ferguson BW, Abba MC (2014) WWOX at the crossroads of cancer, metabolic syndrome related traits and CNS pathologies. Biochim Biophys Acta 1846:188–200

Anderson GW (2008) Thyroid hormone and cerebellar development. Cerebellum 7:60–74

Aqeilan RI, Hagan JP, Aqeilan HA, Pichiorri F, Fong LY, Croce CM (2007) Inactivation of the Wwox gene accelerates forestomach tumor progression in vivo. Cancer Res 67:5606–5610

Aqeilan RI, Hassan MQ, de Bruin A, Hagan JP, Volinia S, Palumbo T et al (2008) The WWOX tumor suppressor is essential for postnatal survival and normal bone metabolism. J Biol Chem 283:21629–21639

Aqeilan RI, Trapasso F, Hussain S, Costinean S, Marshall D, Pekarsky Y et al (2007) Targeted deletion of Wwox reveals a tumor suppressor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:3949–3954

Bahremand A, Ziai P, Payandemehr B, Rahimian R, Amouzegar A, Khezrian M et al (2011) Additive anticonvulsant effects of agmatine and lithium chloride on pentylenetetrazole-induced clonic seizure in mice: involvement of α2-adrenoceptor. Eur J Pharmacol 666:93–99

Bednarek AK, Laflin KJ, Daniel RL, Liao Q, Hawkins KA, Aldaz CM (2000) WWOX, a novel WW domain-containing protein mapping to human chromosome 16q23.3-24.1, a region frequently affected in breast cancer. Cancer Res 60:2140–2145

Ben-Salem S, Al-Shamsi AM, John A, Ali BR, Al-Gazali L (2015) A novel whole exon deletion in WWOX gene causes early epilepsy, intellectual disability and optic atrophy. J Mol Neurosci 56:17–23

Brooks SP, Dunnett SB (2009) Tests to assess motor phenotype in mice: a user's guide. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:519–529

Cam JA, Zerbinatti CV, Knisely JM, Hecimovic S, Li Y, Bu G (2004) The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1B retains beta-amyloid precursor protein at the cell surface and reduces amyloid-beta peptide production. J Biol Chem 279:29639–29646

Chang JY, Lee MH, Lin SR, Yang LY, Sun HS, Sze CI et al (2015) Trafficking protein particle complex 6A delta (TRAPPC6AΔ) is an extracellular plaque-forming protein in the brain. Oncotarget 6:3578–3589

Chang NS, Hsu LJ, Lin YS, Lai FJ, Sheu HM (2007) WW domain-containing oxidoreductase: a candidate tumor suppressor. Trends Mol Med 13:12–22

Chang NS, Pratt N, Heath J, Schultz L, Sleve D, Carey GB et al (2001) Hyaluronidase induction of a WW domain-containing oxidoreductase that enhances tumor necrosis factor cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem 276:3361–3370

Chen ST, Chuang JI, Cheng CL, Hsu LJ, Chang NS (2005) Light-induced retinal damage involves tyrosine 33 phosphorylation, mitochondrial and nuclear translocation of WOX1 in vivo. Neuroscience 130:397–407

Chen ST, Chuang JI, Wang JP, Tsai MS, Li H, Chang NS (2004) Expression of WW domain-containing oxidoreductase WOX1 in the developing murine nervous system. Neuroscience 124:831–839

Chou PY, Lin SR, Lee MH, Schultz L, Sze CI, Chang NS (2019) A p53/TIAF1/WWOX triad exerts cancer suppression but may cause brain protein aggregation due to p53/WWOX functional antagonism. Cell Commun Signal 17:76

Dean SL, McCarthy MM (2008) Steroids, sex and the cerebellar cortex: implications for human disease. Cerebellum 7:38–47

Elsaadany L, El-Said M, Ali R, Kamel H, Ben-Omran T (2016) W44X mutation in the WWOX gene causes intractable seizures and developmental delay: a case report. BMC Med Genet 17:53

Glover TW, Wilson TE, Arlt MF (2017) Fragile sites in cancer: more than meets the eye. Nat Rev Cancer 17:489–501

Greig LC, Woodworth MB, Galazo MJ, Padmanabhan H, Macklis JD (2013) Molecular logic of neocortical projection neuron specification, development and diversity. Nat Rev Neurosci 14:755–769

Guerrini R, Carrozzo R (2001) Epilepsy and genetic malformations of the cerebral cortex. Am J Med Genet 106:160–173

Hills LB, Masri A, Konno K, Kakegawa W, Lam AT, Lim-Melia E et al (2013) Deletions in GRID2 lead to a recessive syndrome of cerebellar ataxia and tonic upgaze in humans. Neurology 81:1378–1386

Howell BW, Hawkes R, Soriano P, Cooper JA (1997) Neuronal position in the developing brain is regulated by mouse disabled-1. Nature 389:733–737

Hsu LJ, Hong Q, Chen ST, Kuo HL, Schultz L, Heath J et al (2017) Hyaluronan activates Hyal-2/WWOX/Smad4 signaling and causes bubbling cell death when the signaling complex is overexpressed. Oncotarget 8:19137–19155

Hsu LJ, Schultz L, Hong Q, Van Moer K, Heath J, Li MY et al (2009) Transforming growth factor beta1 signaling via interaction with cell surface Hyal-2 and recruitment of WWOX/WOX1. J Biol Chem 284:16049–16059

Hur EM, Zhou FQ (2010) GSK3 signaling in neural development. Nat Rev Neurosci 11:539–551

Iatan I, Choi HY, Ruel I, Reddy MV, Kil H, Lee J et al (2014) The WWOX gene modulates high-density lipoprotein and lipid metabolism. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 7:491–504

Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S et al (1998) Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 392:605–608

Koibuchi N, Jingu H, Iwasaki T, Chin WW (2003) Current perspectives on the role of thyroid hormone in growth and development of cerebellum. Cerebellum 2:279–289

Kośla K, Płuciennik E, Styczeń-Binkowska E, Nowakowska M, Orzechowska M, Bednarek AK (2019) The WWOX gene influences cellular pathways in the neuronal differentiation of human neural progenitor cells. Front Cell Neurosci 13:391

Kothur K, Holman K, Farnsworth E, Ho G, Lorentzos M, Troedson C et al (2018) Diagnostic yield of targeted massively parallel sequencing in children with epileptic encephalopathy. Seizure 59:132–140

Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC et al (2019) Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer's disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet 51:414–430

Lai FJ, Cheng CL, Chen ST, Wu CH, Hsu LJ, Lee JY et al (2005) WOX1 is essential for UVB irradiation-induced apoptosis and down-regulated via translational blockade in UVB-induced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 11:5769–5777

Lancaster MA, Gopal DJ, Kim J, Saleem SN, Silhavy JL, Louie CM et al (2011) Defective Wnt-dependent cerebellar midline fusion in a mouse model of Joubert syndrome. Nat Med 17:726–731

Lee JC, Weissglas-Volkov D, Kyttala M, Dastani Z, Cantor RM, Sobel EM et al (2008) WW-domain-containing oxidoreductase is associated with low plasma HDL-C levels. Am J Hum Genet 83:180–192

Lemke G (1993) The molecular genetics of myelination: an update. Glia 7:263–271

Li MY, Lai FJ, Hsu LJ, Lo CP, Cheng CL, Lin SR et al (2009) Dramatic co-activation of WWOX/WOX1 with CREB and NF-κB in delayed loss of small dorsal root ganglion neurons upon sciatic nerve transection in rats. PLoS One 4:e7820

Liu CC, Ho PC, Lee IT, Chen YA, Chu CH, Teng CC et al (2018) WWOX phosphorylation, signaling, and role in neurodegeneration. Front Neurosci 12:563

Lo CP, Hsu LJ, Li MY, Hsu SY, Chuang JI, Tsai MS et al (2008) MPP+-induced neuronal death in rats involves tyrosine 33 phosphorylation of WW domain-containing oxidoreductase. Eur J Neurosci 27:1634–1646

Lo JY, Chou YT, Lai FJ, Hsu LJ (2015) Regulation of cell signaling and apoptosis by tumor suppressor WWOX. Exp Biol Med 240:383–391

Lossi L, Mioletti S, Merighi A (2002) Synapse-independent and synapse-dependent apoptosis of cerebellar granule cells in postnatal rabbits occur at two subsequent but partly overlapping developmental stages. Neuroscience 112:509–523

Luszczki JJ, Wojcki-Cwikla J, Andres MM, Czuczwar SJ (2005) Pharmacological and behavioral characteristics of interactions between vigabatrinand conventional antiepileptic drugs in pentylenetetrazole-induced seizures in mice: an isobolographic analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 30:958–973

Makoukji J, Belle M, Meffre D, Stassart R, Grenier J, Shackleford G et al (2012) Lithium enhances remyelination of peripheral nerves. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:3973–3978

Mallaret M, Synofzik M, Lee J, Sagum CA, Mahajnah M, Sharkia R et al (2014) The tumour suppressor gene WWOX is mutated in autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia with epilepsy and mental retardation. Brain 137:411–419

Manent JB, Wang Y, Chang Y, Paramasivam M, LoTurco JJ (2009) Dcx reexpression reduces subcortical band heterotopia and seizure threshold in an animal model of neuronal migration disorder. Nat Med 15:84–90

Mignot C, Lambert L, Pasquier L, Bienvenu T, Delahaye-Duriez A, Keren B et al (2015) WWOX-related encephalopathies: delineation of the phenotypicalspectrum and emerging genotype-phenotype correlation. J Med Genet 52:61–70

Mizuno Y, Shimizu N (1998) Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 392:605–608

Nosten-Bertrand M, Kappeler C, Dinocourt C, Denis C, Germain J, Phan Dinh Tuy F et al (2008) Epilepsy in Dcx knockout mice associated with discrete lamination defects and enhanced excitability in the hippocampus. PLoS One 3:e2473

Nunez MI, Ludes-Meyers J, Aldaz CM (2006) WWOX protein expression in normal human tissues. J Mol Histol 37:115–125

Peñagarikano O, Abrahams BS, Herman EI, Winden KD, Gdalyahu A, Dong H et al (2011) Absence of CNTNAP2 leads to epilepsy, neuronal migration abnormalities, and core autism-related deficits. Cell 147:235–246

Racine RJ (1972) Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:281–294

Ried K, Finnis M, Hobson L, Mangelsdorf M, Dayan S, Nancarrow JK et al (2000) Common chromosomal fragile site FRA16D sequence: identification of the FOR gene spanning FRA16D and homozygous deletions and translocation breakpoints in cancer cells. Hum Mol Genet 9:1651–1663

Suzuki H, Katayama K, Takenaka M, Amakasu K, Saito K, Suzuki K (2009) A spontaneous mutation of the Wwox gene and audiogenic seizures in rats with lethal dwarfism and epilepsy. Genes Brain Behav 8:650–660

Sze CI, Kuo YM, Hsu LJ, Fu TF, Chiang MF, Chang JY et al (2015) A cascade of protein aggregation bombards mitochondria for neurodegeneration and apoptosis under WWOX deficiency. Cell Death Dis 6:e1881

Sze CI, Su M, Pugazhenthi S, Jambal P, Hsu LJ, Heath J et al (2004) Down-regulation of WW domain-containing oxidoreductase induces tau phosphorylation in vitro. A potential role in Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem 279:30498–30506

Tabarki B, AlHashem A, AlShahwan S, Alkuraya FS, Gedela S, Zuccoli G (2015) Severe CNS involvement in WWOX mutations: description of five new cases. Am J Med Genet A 167A:3209–3213

Tochigi Y, Takamatsu Y, Nakane J, Nakai R, Katayama K, Suzuki H (2019) Loss of Wwox causes defective development of cerebral cortex with hypomyelination in a rat model of lethal dwarfism with epilepsy. Int J Mol Sci 20:3596

Tsai CW, Lai FJ, Sheu HM, Lin YS, Chang TH, Jan MS et al (2013) WWOX suppresses autophagy for inducing apoptosis in methotrexate-treated human squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis 4:e792

Utine GE, Haliloğlu G, Salanci B, Çetinkaya A, Kiper PÖ, Alanay Y et al (2013) A homozygous deletion in GRID2 causes a human phenotype with cerebellar ataxia and atrophy. J Child Neurol 28:926–932

Verkerk AJ, Mathews CA, Joosse M, Eussen BH, Heutink P, Oostra BA (2003) CNTNAP2 is disrupted in a family with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder. Genomics 82:1–9

Wang HY, Juo LI, Lin YT, Hsiao M, Lin JT, Tsai CH et al (2012) WW domain-containing oxidoreductase promotes neuronal differentiation via negative regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Cell Death Differ 19:1049–1059

Wang L, Nomura M, Goto Y, Tanaka K, Sakamoto R, Abe I et al (2011) Smad2 protein disruption in the central nervous system leads to aberrant cerebellar development and early postnatal ataxia in mice. J Biol Chem 286:18766–18774

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Yu-Cheng Lin, Chun-I Sze and Chao-Ching Huang, National Cheng Kung University, for technical expertise and helpful discussions on the seizure models.

Funding

This study was supported by 1) the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, grants MOST103–2320-B-006-002, 104–2320-B-006-016-MY3, 104–2320-B-006-002, 105–2320-B-006-047, 106–2320-B-006-018, 107–2320-B-006-006, 107–2320-B-006-030-MY3 and 108–2320-B-006-021 to L.J.H., and 2) Chi Mei Hospital and National Cheng Kung University Collaborative Research grants CMNCKU9902, 10008, 10204, 10302, 10406, 10502, 10603, 10701 and 10804 to F.J.L. and L.J.H.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YYC designed the experiments, and performed animal behavior tests, seizure models and immunohistochemistry. YTC performed LFB staining, immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay. FJL designed the study and performed transmission electron microscopy. MSJ and SSH provided expertise in the methodology. THC and HCC generated western blot data. IMC recorded Tc-MEPs. PSC, JYL, YTL and PCH performed animal behavior tests. NSC and YSL provided substantial intellectual contribution and experimental funding. LJH generated the Wwox gene knockout mice, oversaw the research design and interpretation of all studies described, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have read the manuscript and accepted responsibility for the manuscript’s content. The authors confirmed there are no conflicts of interest.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Supplementary Methods. Figure S1. Wwox gene deletion causes microcephaly and abnormal brain morphology in mice. Figure S2. Immunofluorescence staining of sagittal cerebellar tissue sections from Wwox+/+ and Wwox-/- mice using an anti-calbindin monoclonal antibody. Figure S3. Increased apoptotic cells in the granular layer of Wwox-/- mouse cerebellum. Figure S4. A lack of full separation of cerebral hemispheres is evident in Wwox-/- mice. Figure S5. The development of Wwox-/- mouse central nervous system is defective during the embryonic stages. Figure S6. Wwox-/- mouse neocortical neurons retain high proliferative activity after E16.5 and have poor mobility during development. Figure S7. Wwox loss leads to the increased DCX protein levels in mouse brain tissues at postnatal day 14. Figure S8. Neuronal heterotopia can be observed in the cortex of Wwox knockout mouse brain. Figure S9. Increased neuronal apoptosis is detected in Wwox knockout mouse brain.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, YY., Chou, YT., Lai, FJ. et al. Wwox deficiency leads to neurodevelopmental and degenerative neuropathies and glycogen synthase kinase 3β-mediated epileptic seizure activity in mice. acta neuropathol commun 8, 6 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-0883-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-020-0883-3