Abstract

Background

We evaluated the antitumor activity and safety of avelumab, a human anti–PD-L1 IgG1 antibody, as first-line switch-maintenance (1 L-mn) or second-line (2 L) treatment in patients with advanced gastric/gastroesophageal cancer (GC/GEJC) previously treated with chemotherapy.

Methods

In a phase 1b expansion cohort, patients without (1 L-mn) or with (2 L) disease progression following first-line chemotherapy for advanced GC/GEJC received avelumab 10 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks. Endpoints included best overall response, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety.

Results

Overall, 150 patients were enrolled (1 L-mn, n = 90; 2 L, n = 60) and median follow-up in the 1 L-mn and 2 L subgroups was 36.0 and 33.7 months, respectively. The confirmed objective response rate was 6.7% in both subgroups (95% CI, 2.5–13.9% and 1.8–16.2%, respectively), including complete responses in 2.2% of the 1 L-mn subgroup (n = 2). In the 1 L-mn and 2 L subgroups, median duration of response was 21.4 months (95% CI, 4.0–not estimable) and 3.5 months (95% CI, 2.8–8.3) and disease control rates were 56.7 and 28.3%, respectively. Median PFS in the 1 L-mn and 2 L subgroups was 2.8 months (95% CI, 2.3–4.1) and 1.4 months (95% CI, 1.3–1.5), with 6-month PFS rates of 23.0% (95% CI, 14.7–32.4%) and 7.9% (95% CI, 2.6–17.2%), and median OS was 11.1 months (95% CI, 8.9–13.7) and 6.6 months (95% CI, 5.4–9.4), respectively. In the 1 L-mn subgroup, median OS measured from start of 1 L chemotherapy was 18.7 months (95% CI, 15.4–20.6). Across both subgroups, 20.7% had an infusion-related reaction of any grade. Other common treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) of any grade included fatigue (10.0%) and nausea (6.7%). Treatment-related serious adverse events occurred in 4.0% of patients. Overall, 8.7% had a grade ≥3 TRAE, including 1 treatment-related death.

Conclusion

Avelumab showed clinical activity and an acceptable safety profile in patients with GC/GEJC.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01772004; registered 21 January 2013.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric cancer (GC) is an aggressive disease that represents the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Gastroesophageal junction cancer (GEJC) has similar biology, prognosis, and treatment guidelines as GC [2, 3]. First-line (1 L) standard of care for advanced inoperable GC/GEJC is based on combination fluoropyrimidine and platinum treatment, with trastuzumab added for HER2+ tumors. Second-line (2 L) options include regimens based on irinotecan, taxanes, and/or ramucirumab [2, 3]. However, cytotoxic regimens are associated with cumulative toxicity that may restrict long-term treatment, resulting in limited duration of response and overall survival (OS). Maintenance therapy, ie, continued treatment with an agent administered in the 1 L induction regimen or sequential treatment with a different agent until progression (switch maintenance), has the potential to extend durations of response and OS, particularly when an agent with a different mechanism of action is employed, while avoiding potential additive toxicity associated with further chemotherapy or combination treatment. As such, maintenance therapy has become an established strategy for several advanced tumors [4, 5]. Although the role of maintenance therapy in treating GC/GEJC is less well defined, observational and retrospective studies of maintenance fluoropyrimidine treatment in advanced GC/GEJC have shown that this approach is feasible and may improve progression-free survival (PFS) compared with observation alone [6,7,8].

In recent years, much attention has been focused on anticancer therapies that activate the immune response. In a randomized phase 2 study of patients with advanced GC/GEJC, switch-maintenance ipilimumab (anti–CTLA-4) after 1 L chemotherapy did not improve immune-related PFS or OS compared with best supportive care, which included continued fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy in most patients [9]. PD-L1 is a key therapeutic target for reactivating antitumor immune responses [10]. Additionally, PD-L1 is expressed in ≈30 to 60% of GC/GEJC specimens, with a higher frequency seen in certain pathological and genomic subtypes [11]. Immunotherapy with anti–PD-1 antibodies has been associated with durable antitumor responses in early-phase studies of patients with GC/GEJC [10, 12, 13].

Avelumab is a human anti–PD-L1 monoclonal antibody that has been approved in various countries for the treatment of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma and in the United States and Canada for the treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma progressing after platinum-containing chemotherapy. In phase 1 and 2 studies across various advanced cancers, avelumab has demonstrated a tolerable safety profile and durable antitumor activity [14,15,16]. In preclinical studies, avelumab activated both adaptive and innate immune effector cells [17, 18], suggesting an additional mechanism of action compared with other approved anti–PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies.

To investigate the efficacy and safety of avelumab in the treatment of advanced GC/GEJC, we enrolled a cohort of patients in the phase 1 JAVELIN Solid Tumor trial. Patients were enrolled following 1 L chemotherapy; those without disease progression received avelumab as 1 L switch maintenance (1 L-mn subgroup), and those with disease progression received avelumab as 2 L treatment (2 L subgroup). To our knowledge, this is the first study of an anti–PD-L1 agent administered as switch-maintenance therapy in this disease.

Methods

Study design and patients

JAVELIN Solid Tumor (NCT01772004) is an international, open-label, phase 1 trial. In the phase 1b, nonrandomized expansion cohort reported here, eligible patients had histologically confirmed, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic GC/GEJC, and previous treatment with 1 L combination chemotherapy; patients with prior neoadjuvant platinum-based doublet or triplet chemotherapy who were not candidates for surgery were also eligible. Patients should not have received >1 line of prior treatment for metastatic disease, and patients with prior checkpoint inhibitor or trastuzumab treatment were ineligible (Additional file 1: Table S1). Patients in the 2 L subgroup were not permitted to have received anticancer treatment within 28 days before the start of study treatment, whereas in the 1 L-mn subgroup, patients were permitted to be enrolled within 28 days if all toxicity from prior therapy had resolved to grade ≤1. A fresh or archival tumor specimen was required, but patients were not preselected based on PD-L1 status (ie, all-comer design). Patients were enrolled in accordance with an approved protocol, international standards of good clinical practice, and institutional safety monitoring, and written informed consent was obtained. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each center.

Procedures and assessments

Patients received avelumab 10 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks until confirmed disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or protocol-based criteria for withdrawal [15]. Premedication with diphenhydramine and acetaminophen was required 30 to 60 min before all avelumab infusions.

Safety was assessed at each biweekly trial visit and included assessment of adverse events (AEs), physical examination, clinical laboratory tests (hematology, hepatic panels, and serum chemistry), and documentation of concurrent medications. AEs and laboratory abnormalities were classified and graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. A serious AE (SAE) was defined as any untoward event that was life-threatening, required hospitalization, resulted in disability, was a congenital anomaly, or resulted in death. Immune-related AEs were identified using a prespecified list of Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities terms plus medical review. Clinical activity was assessed by investigators using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1. Radiographic tumor assessments were performed at baseline and every 6 weeks. In patients achieving a partial response (PR) or complete response (CR), a confirmatory CT or MRI scan was done ≥28 days later (preferably at the scheduled 6-week interval). PD-L1 expression was assessed in tumor cells using a proprietary immunohistochemistry assay (PD-L1 IHC 73-10; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), as described previously [15, 19]; in this report, PD-L1 status was defined using cutoffs of ≥1% of tumor cells positive for partial or complete membrane PD-L1 staining of any intensity. HER2 and microsatellite status were recorded retrospectively from medical records when available.

Outcomes

Primary endpoints for the entire JAVELIN Solid Tumor trial were dose-limiting toxicities during the first 3 weeks of treatment in the phase 1a dose-escalation part (reported previously [20]) and confirmed best overall response adjudicated by independent review in specified efficacy expansion cohorts (not including the GC/GEJC cohort reported here). Secondary endpoints assessed in the current cohort included investigator-assessed best overall response, duration of response, PFS, OS, safety, and evaluation of PD-L1 expression [15].

Statistical methods

Enrollment of 150 patients was planned for this cohort based on the anticipated sample size required to estimate and provide 95% Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals (CIs) for potential objective response rates (ORR; proportion of patients with a confirmed CR or PR; eg, 10% [5.7–16.0%] for 15 responders or 20% [13.9–27.3%] for 30 responders). Safety and antitumor activity were analyzed in all patients who received ≥1 dose of avelumab. Time-to-event endpoints (PFS, OS, duration of response, and duration of follow-up) were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and CIs for the median were calculated using the Brookmeyer–Crowley method.

Results

Patients

Between 13 February 2014 and 11 August 2015, 150 patients with histologically confirmed GC/GEJC were enrolled, including 90 without disease progression after 1 L chemotherapy (1 L-mn subgroup) and 60 with progressive disease (2 L subgroup), per investigator assessment (Table 1). In the 1 L-mn subgroup, 27.8% had achieved a PR with prior chemotherapy; in the 2 L subgroup, prior responses were PR in 13.3% and CR in 1.7%. The median interval between end of prior chemotherapy and start of avelumab was 45 days (1 L-mn subgroup) and 77 days (2 L subgroup). Across both subgroups, 30.7% had PD-L1+ tumors.

At data cutoff (30 September 2017), patients in the 1 L-mn and 2 L subgroups had received a median (range) of 7 (1–79) and 4.5 (1–44) avelumab doses, and median duration of treatment was 3.2 months (interquartile range [IQR], 1.4–6.1) and 2.2 months (IQR, 1.4–5.2), respectively. Median duration of follow-up was 36.0 months (IQR, 33.7–37.7) in the 1 L-mn subgroup and 33.7 months (IQR, 27.9–34.9) in the 2 L subgroup. In both subgroups, the most common reason for treatment discontinuation was disease progression (1 L-mn, 75.6%; 2 L, 71.7%); other reasons were AE (13.3%, 10.0%), death (3.3%, 8.3%), withdrawal of consent (1.1%, 6.7%), loss to follow-up (0%, 1.7%), protocol noncompliance (1.1%, 0%), and physician decision (0%, 1.7%). Five patients remained on avelumab treatment at data cutoff, all in the 1 L-mn subgroup (5.6%).

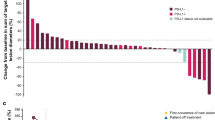

Antitumor activity: 1 L-mn subgroup

The confirmed ORR (additional effect after the end of chemotherapy) was 6.7% (n = 6; 95% CI, 2.5–13.9%) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Notably, 2 patients (2.2%) had a CR; both patients were Asian and had stable disease (SD) as best response to prior chemotherapy, and PD-L1 status was positive in 1 patient and not evaluable in the other. Four patients (4.4%) had a PR, which represented additional tumor shrinkage following prior chemotherapy; best response to prior chemotherapy in these patients was PR (n = 2) and SD (n = 2) (Additional file 1: Table S3). Forty-five patients (50.0%) had SD of any duration as best response (disease control rate, 56.7%). Early and durable responses were observed (Fig. 1a and Additional file 1: Figure S1A), with a median time to response of 1.4 months (IQR, 1.3–4.1), a median duration of response of 21.4 months (95% CI, 4.0–not estimable), and an estimated 66.7% (95% CI, 19.5–90.4%) of responses lasting ≥6 months. Responses were ongoing at data cutoff in 2 patients, including 1 patient with a CR. In evaluable patients with PD-L1+ or PD-L1− tumors, confirmed ORR was 7.7% (2/26; 95% CI, 0.9–25.1%) vs 3.9% (2/51; 95% CI, 0.5–13.5%). Of 81 patients evaluable for change in size of target lesions, 13 (16.0%) had shrinkage of ≥30% and 37 (45.7%) had shrinkage of any level (Additional file 1: Figure S2A). No correlation was seen between response to prior chemotherapy and tumor shrinkage on avelumab.

Change in sum of target lesion diameters over time with avelumab in evaluable patients. a First-line switch-maintenance subgroup (n = 81). b Second-line subgroup (n = 52). Color coding is based on best overall response per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1. Dotted lines indicate the 3-month timepoint and changes in target lesion size of −30, 0, and +20%

Two patients had prolonged shrinkage in target lesions with avelumab after documented progressive disease (due to >30% increase in target lesion size vs baseline at weeks 7–13 in 1 patient and a new lesion in the other patient), suggestive of pseudoprogression. Duration of avelumab treatment in these 2 patients was 36.2 months (ongoing) and 23.5 months, respectively. Another patient had SD before disease progression at week 13 (due to a new lesion), followed by a 100% reduction in target lesions sustained for >6 months.

Median PFS and OS measured from start of avelumab therapy (ie, not including prior chemotherapy) were 2.8 months (95% CI, 2.3–4.1) and 11.1 months (95% CI, 8.9–13.7), respectively. The 6-month and 12-month PFS rates were 23.0% (95% CI, 14.7–32.4%) and 13.0% (95% CI, 6.6–21.6%), respectively, and the 12-month OS rate was 46.2% (95% CI, 35.6–56.1%) (Fig. 2a and b). In patients from Asian and non-Asian countries, median OS was 12.4 months (95% CI, 9.7–20.0) and 9.4 months (95% CI, 7.4–13.7), respectively. Median OS measured from start of 1 L chemotherapy was 18.7 months (95% CI, 15.4–20.6) overall (Fig. 2c), and 20.6 months (95% CI, 17.1–28.1) and 15.8 months (95% CI, 12.3–19.9) in patients from Asian and non-Asian countries, respectively. In PD-L1+ and PD-L1− subgroups, median PFS was 3.0 (95% CI, 1.4–4.1) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.4–3.6) months (hazard ratio [HR], 0.844 [95% CI, 0.505–1.411]) and median OS was 15.9 (95% CI, 11.4–20.7) and 10.4 (95% CI, 8.3–12.4) months (HR, 0.588 [95% CI, 0.342–1.009]), respectively (Additional file 1: Figures S3A and S4A).

Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). a PFS from start of avelumab in the first-line switch-maintenance (1 L-mn) subgroup (n = 90). b OS from start of avelumab in the 1 L-mn subgroup (n = 90). c OS from start of 1 L chemotherapy in the 1 L-mn subgroup (n = 90). d PFS in the second-line (2 L) subgroup (n = 60). e OS in the 2 L subgroup (n = 60)

Antitumor activity: 2 L subgroup

The ORR was 6.7% (95% CI, 1.8–16.2%; PR in 4 patients), and the disease control rate was 28.3% (13 patients [21.7%] had SD as best response) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Median time to and duration of response were 2.0 months (IQR, 1.3–2.7) and 3.5 months (95% CI, 2.8–8.3), respectively. An estimated 25.0% (95% CI, 0.9–66.5%) of responses lasted ≥6 months (Fig. 1b and Additional file 1: Figure S1B). Of 52 evaluable patients, 7 (13.5%) had target lesion shrinkage of ≥30% and 16 (30.8%) had shrinkage of any level (Additional file 1: Figure S2B). Median PFS was 1.4 months (95% CI, 1.3–1.5), and 6-month and 12-month PFS rates were 7.9% (95% CI, 2.6–17.2%) and 2.0% (95% CI, 0.2–9.1%), respectively (Fig. 2d). Median OS was 6.6 months (95% CI, 5.4–9.4), and the 12-month OS rate was 25.6% (95% CI, 14.9–37.6%) (Fig. 2e). In patients from Asian and non-Asian countries, median OS was 8.3 months (95% CI, 2.0–10.4) and 6.3 months (95% CI, 4.3–9.4), respectively. No significant difference was seen in PFS and OS based on PD-L1 status (Additional file 1: Figures S3B and S4B).

Safety

Across both subgroups, 85 of 150 patients (56.7%) had a treatment-related AE (TRAE) of any grade, including 57 of 90 (63.3%) in the 1 L-mn subgroup and 28 of 60 (46.7%) in the 2 L subgroup. Patterns of TRAEs were similar in both subgroups (Table 2 and Additional file 1: Table S4). Overall, infusion-related reactions and related symptoms occurred in 20.7%. Time to onset of infusion-related reaction was first or second infusion in 29 of 31 cases (93.5%). Other common TRAEs (any grade in ≥5%) were fatigue (10.0%), nausea (6.7%), chills (6.0%), and pruritus (5.3%). Thirteen patients (8.7%) had a grade ≥3 TRAE (1 L-mn subgroup, 8 [8.9%]; 2 L subgroup, 5 [8.3%]), most commonly fatigue, asthenia, anemia, and elevated lipase (n = 2 each; 1.3%). One patient (0.7%) had a grade 3 infusion-related reaction (1 L-mn subgroup). Two patients (both 2 L subgroup) had a grade 4 TRAE: elevated lipase (n = 1) and decreased platelet count (n = 1). Overall, 81 patients (54.0%) had a SAE, which was related to treatment in 6 patients (4.0%; 3 in each subgroup). One treatment-related death occurred (1 L-mn subgroup) in a patient with peritoneal metastases and ascites at study entry who developed grade 5 autoimmune hepatitis and hepatic failure. Twenty-three patients (15.3%) had an immune-related AE, including grade ≥3 in 3 patients (2.0%): colitis (grade 3, 1 L-mn), autoimmune hepatitis/hepatic failure (grade 5, 1 L-mn), and adrenal insufficiency (grade 3, 2 L). Avelumab was permanently discontinued following a TRAE in 8 patients (5.3% overall; 1 L-mn: 6 [6.7%]; 2 L: 2 [3.3%]), of whom 3 (2.0%) discontinued because of an infusion-related reaction.

Discussion

In this single-arm phase 1b cohort of 150 patients with previously treated advanced GC/GEJC, avelumab showed evidence of durable antitumor activity as 1 L-mn and 2 L therapy. The ORR was 6.7% in both subgroups, although median durations of response were 21.4 months in the 1 L-mn subgroup and 3.5 months in the 2 L subgroup. Remarkably, 2 patients (2.2%) in the 1 L-mn subgroup had a CR after achieving only SD on prior chemotherapy. Avelumab showed a tolerable safety profile, including a low rate of grade ≥3 TRAEs (8.7%) and immune-related AEs (any grade, 15.3%; grade ≥3, 2.0%), similar to observations in other tumor types [21]. Detailed guidance for recognizing and managing immune-related AEs with this class of agents have been published by consensus groups [22, 23]. The incidence of TRAEs of any grade was higher in the 1 L-mn subgroup compared with the 2 L subgroup (63.3% vs 46.7%), which may be due to the longer treatment duration and shorter interval from end of prior chemotherapy to start of avelumab in the 1 L-mn subgroup, although the incidence of grade ≥3 TRAEs was similar in both subgroups (8.9% vs 8.3%, respectively).

Approximately 70% of patients achieve a response or SD with standard 1 L chemotherapy [24, 25]; however, duration of OS is usually short [2, 3]. In the 1 L-mn subgroup, median PFS was 2.8 months (6-month rate, 23.0%), median OS measured from the start of avelumab was 11.1 months (12-month rate, 46.2%), and median OS measured from the start of prior chemotherapy was 18.7 months. Thus, the OS seen in the 1 L-mn subgroup, which enrolled patients without disease progression following chemotherapy, is encouraging for this subgroup of patients. Administering immunotherapy sequentially after completion of 1 L chemotherapy may enhance the immunostimulatory effects of chemotherapy while reducing the toxicity that may result when anti–PD-1 antibodies are administered in combination with other agents (eg, chemotherapy or ipilimumab) [26, 27]. To further assess this strategy, a randomized phase 3 trial is comparing avelumab switch-maintenance treatment with continuation of 1 L platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced GC/GEJC (JAVELIN Gastric 100; NCT02625610).

Several early-phase studies assessed anti–PD-1 monotherapy in patients with chemotherapy-treated (later-line) GC/GEJC outside of the maintenance setting [12, 13, 27, 28], and median PFS and OS reported in non–PD-L1–selected populations were 2.0 months and 5.5–6.2 months, respectively. Survival data for avelumab (anti–PD-L1) in the 2 L subgroup (median PFS and OS of 1.4 and 6.6 months, respectively) appear consistent with these studies. Subsequently, phase 3 trials assessing later-line treatment with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy in advanced GC/GEJC were initiated. In a randomized phase 3 trial of nivolumab vs placebo as third-line or later treatment in Asian patients with GC/GEJC (n = 493), the ORR was 11.2% vs 0% (P<.0001), median PFS was 1.6 vs 1.5 months (P<.0001), and median OS was 5.3 vs 4.1 months (P<.0001), respectively [13]. However, to date no improvement in OS has been shown in studies comparing single-agent checkpoint inhibitors with chemotherapy, such as trials of 2 L pembrolizumab vs paclitaxel (KEYNOTE-061) [29] and third-line avelumab vs physician choice of chemotherapy (JAVELIN Gastric 300) [30]. Results from phase 3 trials assessing alternative anti–PD-1/PD-L1–based regimens in the 1 L setting, such as switch-maintenance (sequential) or combination (concurrent) approaches, are needed.

Available data indicate that the benefits seen with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in GC/GEJC may be limited to a small proportion of patients. Thus, predictive biomarkers to identify subpopulations more likely to respond to immunotherapy are a focus of ongoing research [10]. In this study, clinical activity was seen both in PD-L1+ and PD-L1− tumors including similar ORR and PFS and a nonsignificant trend in the 1 L-mn subgroup for longer OS in PD-L1+ tumors. It should be noted that the PD-L1 assay used in this study differs from those used in studies of other approved anti–PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies. Also, in the present study, PD-L1 status was based solely on tumor cell expression, whereas in studies of pembrolizumab in patients with GC/GEJC, in which antitumor activity was associated with PD-L1 expression, PD-L1 status was determined based on expression on tumor or immune cells (combined positive score). In addition, responses to pembrolizumab in patients with GC/GEJC have been associated with microsatellite instability–high/mismatch repair–deficient status and Epstein-Barr virus status [12, 31]. In the current trial, microsatellite status was available for only a small number of patients and findings were inconclusive. Assessment of novel biomarkers is planned for future avelumab studies in GC/GEJC.

Conclusion

The data in the present phase 1b study demonstrate that avelumab administered as maintenance therapy (after disease control with standard chemotherapy) has antitumor activity and acceptable safety in patients with advanced GC/GEJC, supporting further investigations of this treatment approach.

Abbreviations

- 1 L-mn:

-

First-line switch-maintenance

- 2 L:

-

Second-line

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- CR:

-

Complete response

- ECOG PS:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- GC:

-

Gastric cancer

- GEJC:

-

Gastroesophageal junction cancer

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PR:

-

Partial response

- SAE:

-

Serious adverse event

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- TRAE:

-

Treatment-related adverse event

References

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Gastric Cancer. V2.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2018.

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers. V2.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/esophageal.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2018.

Paz-Ares LG, de Marinis F, Dediu M, Thomas M, Pujol JL, Bidoli P, et al. PARAMOUNT: final overall survival results of the phase III study of maintenance pemetrexed versus placebo immediately after induction treatment with pemetrexed plus cisplatin for advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2895–902.

Simkens LH, van Tinteren H, May A, ten Tije AJ, Creemers GJ, Loosveld OJ, et al. Maintenance treatment with capecitabine and bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer (CAIRO3): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial of the Dutch colorectal cancer group. Lancet. 2015;385:1843–52.

Meulendijks D, de Groot JW, Los M, Boers JE, Beerepoot LV, Polee MB, et al. Bevacizumab combined with docetaxel, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine, followed by maintenance with capecitabine and bevacizumab, as first-line treatment of patients with advanced HER2-negative gastric cancer: a multicenter phase 2 study. Cancer. 2016;122:1434–43.

Eren OO, Ozturk MA, Sonmez OU, Oyan B. Safety, feasibility, and efficacy of capecitabine maintenance in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a retrospective study. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e1493–7.

Li W, Zhao X, Wang H, Liu X, Zhao X, Huang M, et al. Maintenance treatment of uracil and tegafur (UFT) in responders following first-line fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomized phase 2 study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:37826–34.

Bang YJ, Cho JY, Kim YH, Kim JW, Di Bartolomeo M, Ajani JA, et al. Efficacy of sequential ipilimumab monotherapy vs best supportive care for unresectable locally advanced/metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:5671–8.

Alsina M, Moehler M, Hierro C, Guardeño R, Tabernero J. Immunotherapy for gastric cancer: a focus on immune checkpoints. Target Oncol. 2016;11:469–77.

Boger C, Behrens HM, Mathiak M, Krüger S, Kalthoff H, Röcken C. PD-L1 is an independent prognostic predictor in gastric cancer of Western patients. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24269–83.

Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW, Muro K, Satoh T, Machado M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE-059 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e180013.

Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, Ryu MH, Chao Y, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2461–71.

Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Terheyden P, D'Angelo SP, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multicentre, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1374–85.

Gulley JL, Rajan A, Spigel DR, Iannotti N, Chandler J, Wong DJL, et al. Avelumab for patients with previously treated metastatic or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer (JAVELIN solid tumor): dose-expansion cohort of a multicentre, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:599–610.

Patel MR, Ellerton J, Infante JR, Agrawal M, Gordon M, Aljumaily R, et al. Avelumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum failure (JAVELIN solid tumor): pooled results from two expansion cohorts of an open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:51–64.

Boyerinas B, Jochems C, Fantini M, Heery CR, Gulley JL, Tsang KY, et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activity of a novel anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab (MSB0010718C) on human tumor cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1148–57.

Vandeveer AJ, Fallon JK, Tighe R, Sabzevari H, Schlom J, Greiner JW. Systemic immunotherapy of non-muscle invasive mouse bladder cancer with avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:452–62.

Apolo AB, Infante JR, Balmanoukian A, Patel MR, Wang D, Kelly K, et al. Avelumab, an anti-programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in patients with refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma: results from a multicenter, phase 1b study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2117–24.

Heery CR, O’Sullivan-Coyne G, Madan RA, Cordes L, Rajan A, Rauckhorst M, et al. Avelumab for metastatic or locally advanced previously treated solid tumours (JAVELIN solid tumor): a phase 1a, multicohort, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:587–97.

Kelly K, Infante JR, Taylor MH, Patel MR, Wong DJ, Iannotti N, et al. Safety profile of avelumab in patients with advanced solid tumors: a pooled analysis of data from the phase 1 JAVELIN solid tumor and phase 2 JAVELIN Merkel 200 clinical trials. Cancer. 2018;124:2010–7.

Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, Bingham CO 3rd, Brogdon C, Dadu R, et al. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) toxicity management working group. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:95.

Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1714–68.

Lordick F, Kang YK, Chung HC, Salman P, Oh SC, Bodoky G, et al. Capecitabine and cisplatin with or without cetuximab for patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer (EXPAND): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:490–9.

Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, Rha SY, Sawaki A, Park SR, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–76.

Wainberg ZA, Jalal S, Muro K, Yoon HH, Garrido M, Golan T, et al. KEYNOTE-059 update: efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal (G/GEJ) cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28 [abstract LBA28].

Janjigian YY, Ott PA, Calvo E, Kim JW, Ascierto PA, Sharma P, et al. Nivolumab ± ipilimumab in pts with advanced (adv)/metastatic chemotherapy-refractory (CTx-R) gastric (G), esophageal (E), or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) cancer: CheckMate 032 study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(Suppl 15) [abstract 4014].

Muro K, Chung HC, Shankaran V, Geva R, Catenacci D, Gupta S, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with PD-L1-positive advanced gastric cancer (KEYNOTE-012): a multicentre, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:717–26.

Shitara K, Ozguroglu M, Bang YJ, Di Bartolomeo M, Mandalà M, Ryu MH, et al. Pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel for previously treated, advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (KEYNOTE-061): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:123–33.

Bang Y, Yañez Ruiz E, Van Cutsem E, Lee KW, Wyrwicz L, Schenker M, et al. Phase 3, randomised trial of avelumab versus physician’s choice of chemotherapy as third-line treatment for patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer: primary analysis of JAVELIN Gastric 300. Ann Oncol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy264.

Kim ST, Cristescu R, Bass AJ, Kim KM, Odegaard JI, Kim K, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat Med. 2018;24:1449–58.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families, investigators, coinvestigators, and study teams at each of the participating centers and at Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany, and EMD Serono Research & Development Institute, Inc., Billerica, MA, USA (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Funding

This trial was sponsored by Merck KGaA and is part of an alliance between Merck KGaA and Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY, USA. Medical writing support was provided by ClinicalThinking and was funded by Merck KGaA and Pfizer.

Availability of data and materials

For all new products or new indications approved in both the European Union and the United States after January 1, 2014, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany will share patient-level and study-level data after deidentification, as well as redacted study protocols and clinical study reports from clinical trials in patients. These data will be shared with qualified scientific and medical researchers, upon researcher’s request, as necessary for conducting legitimate research. Such requests must be submitted in writing to the company’s data sharing portal. More information can be found at https://www.merckgroup.com/en/research/our-approach-to-research-and-development/healthcare/clinical-trials/commitment-responsible-data-sharing.html. Where Merck KGaA has a co-research, co-development or co-marketing/co-promotion agreement or where the product has been out-licensed, it is recognized that the responsibility for disclosure may be dependent on the agreement between parties. Under these circumstances, Merck KGaA will endeavour to gain agreement to share data in response to requests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Provision of study materials or patients: HCC, HTA, JL, SYR, DYO, LW, YKK, KWL, JRI, SSL, MK, UK, BM, AM, RP, DS, HS. Collection and assembly of data: all authors. Data analysis and interpretation: all authors. Manuscript writing: all authors. Final approval of manuscript: all authors. Accountable for all aspects of the work: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The trial was conducted in accordance with the ethics principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonisation Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee of each center. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HCC: consultant/advisory role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion Healthcare, Eli Lilly, Merck & Co, Merck KGaA, Quintiles, Taiho Pharmaceutical; speakers bureau: Eli Lilly, Foundation Medicine, Merck KGaA; research grants: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck & Co, Merck KGaA, Ono Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical.

YKK: consulting or advisory role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Ono Pharmaceutical, Roche; research funding: Bayer, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi.

KWL: research funding: AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Daiichi Sankyo, Five Prime Therapeutics, Green Cross Corp, Macrogenics, Merck KGaA, Merck & Co, Ono Pharmaceutical, Taiho Pharmaceutical.

UK: honoraria: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Glycotope GmbH, Merck KGaA, Merck & Co, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech; consulting or advisory role: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Serono, Merck & Co, Pfizer; speakers bureau: AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Glycotope GmbH, Merck Serono, MSD Oncology, Novartis; research funding: Pfizer; travel, accommodations, expenses: AstraZeneca, Merck KGaA, Merck & Co.

BM: honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck & Co, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche; consulting or advisory role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck & Co, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche; travel, accommodations, expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche.

AM: speakers bureau: Genentech.

RP: honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche/Genentech; consulting or advisory role: AstraZeneca, BioMarin, Clovis Oncology, Karus Therapeutics, Mission Therapeutics, Merck & Co, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, Tesaro, Vertex; speakers bureau: Novartis; research funding: AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Clovis Oncology, Eisai, Etherapeutics, Ipsen, Vertex; patents, royalties, other intellectual property: named on patent for use of PARP inhibitor (rucaparib); travel, accommodations, expenses: Merck & Co, Roche/Genentech.

ABG: employment: EMD Serono Inc. (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) when the study was performed; stock ownership: Halozyme Therapeutics.

HX: employment: EMD Serono Inc. (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

JH: employment: EMD Serono Inc. (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

VC: employment: EMD Serono Inc. (a business of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) when the study was performed; current employment at AstraZeneca; stock and other ownership interests: Bristol-Myers Squibb.

HTA, JL, SYR, DYO, LW, JRI, SSL, MK, DS, and HS declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Eligibility criteria. Table S2. Response to avelumab in the 1 L-mn and 2 L subgroups. Table S3. Best response to avelumab compared with best response to prior anticancer therapy in the 1 L-mn subgroup. Table S4. Overall summary of safety. Figure S1. Time to and duration of response in responding patients. Figure S2. Best change in sum of target lesion diameters from baseline with avelumab in evaluable patients. Figure S3. Progression-free survival by PD-L1 expression status (≥1% tumor cell cutoff) in evaluable patients. Figure S4. Overall survival by PD-L1 expression status (≥1% tumor cell cutoff) in evaluable patients. (DOCX 794 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, H.C., Arkenau, HT., Lee, J. et al. Avelumab (anti–PD-L1) as first-line switch-maintenance or second-line therapy in patients with advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase 1b results from the JAVELIN Solid Tumor trial. j. immunotherapy cancer 7, 30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-019-0508-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-019-0508-1