Abstract

Background

The American trypanosomiasis is a zoonosis caused by the protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi). The disease is widely distributed throughout the American continent, affecting a wide range of hosts, including dogs. It is present in the canine population in the State of Yucatan, Mexico. However, no significant studies in owned dogs have been performed in the metropolitan area of Merida. A transversal study was conducted in 370 owned dogs from Merida, Yucatan, Mexico.

Methods

A cross-sectional study including 370 dogs was performed in a major city of Yucatan, Mexico, to detect IgG antibodies against T. cruzi. A commercial ELISA test kit was used and a chi-square test used to evaluate associated risk factors; odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) were also estimated.

Results

The indirect ELISA and western blot (WB) tests were used to detect specific immunoglobulin G antibodies against T. cruzi in serum samples. A prevalence of 12.2 % was found; age and area of residence were statistically associated with seropositivity in dogs (p <0.05).

Conclusions

Results from the present study suggests the presence and abundance of the vector in urban conditions where a high number of seropositive cases of T. cruzi cases were found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

American trypanosomiasis, or Chagas disease, is a zoonosis of public health concern caused by the protozoon Trypanosoma cruzi and transmitted by a bloodsucking bug from the Triatominae subfamily. In Yucatan, Mexico, the disease is endemic and affects a wide range of hosts, including dogs and humans [1, 2]. Triatominaes may prefer to feed on dogs, which then become reservoirs of the agent and become involved in the intra-domiciliary transmission cycle [3–6]. Once infected, dogs may develop clinical signs of the disease, which are mainly characterized by cardiac insufficiency. If the dog survives, it can become chronically infected [7]. Traditionally, rural areas are considered to be at higher risk for infection through the vector’s bite, but this risk is also present in stray dogs from urban areas [1, 8]. Owned dogs are in close contact with their owners, and thus, they are at a higher risk of transmitting diseases, including Chagas [9, 10]. A preliminary study in the city of Merida indicated that 34 % of owned dogs and 8 % of their owners were infected with American trypanosomiasis [2].

The objectives of this study were to determine the seroprevalence of American trypanosomiasis in owned dogs from the city of Merida, Yucatan, Mexico, and to determine the associated risk factors.

Methods

Study area

The study was conducted in the city of Merida, located northwest of the state of Yucatan, Mexico (19° 30′ and 21° 35′ north latitude, 87° 30′ and 90° 24′ west longitude). The city’s climate is warm and sub-humid with summer rains and is 6 m above sea level [11].

Sampling

A total of 370 owned dogs from the metropolitan area of Merida were included. Sample size was determined considering a population of at least 200,000 owned dog in the city with an expected prevalence of 17 %, with a 99 % of confidence level and 5 % of precision [1, 12]. Blood samples were collected from the cephalic vein during a spaying campaign. Serum was obtained by centrifugation of the samples at 2700 g for 5 min. During the sample collection, owners were asked their home address and data about their dogs (age and sex). Blood samples from dogs were collected with the consent of their owners after explaining the objectives of the study. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (CB-CCBA I-2014-003).

Serological detection

The immunoglobulin G (IgG) indirect ELISA test was performed as previously described using the commercial ELISA test kit (Chagatest ELISA recombinant v.3.0, Wiener, Argentina) [1, 8]. Cultured parasites of the reference T. cruzi Y strain were used as antigens and the methodology was previously described [1]. To confirm the serologic diagnosis, the western blot (WB) method was used according to a methodology previously described by Teixeira et al. [13].

Statistical analysis

The study was designed as a cross-sectional study, and the results were analyzed using descriptive statistics to determine the prevalence of T. cruzi. A case was considered true positive when it was positive for two serological tests (ELISA and WB). To determine the association among the studied variables (age, gender and area of residence of the dogs) and the presence of specific antibodies to T. cruzi, a chi-square test was used; the odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confidence interval (CI) were also estimated. SPSS v.15.0 was used with a significance level of p <0.05.

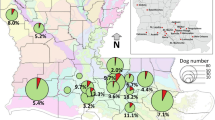

The area of residence was divided into four zones considering their socioeconomical status previously reported, the building characteristics of households and closeness to forestry areas [12]. Southeast and southwest zones are of lower socioeconomical status with several houses of straw roof and earthen floor at the periphery of the city and with abundant natural forestry.

Results and discussion

Among the 370 samples, seroprevalence was 12.2 % (95 % CI: 9.5–15.1 %). An example of the western blot is shown in Fig. 1. Regarding the risk factors considered, only the area of the residence (southeast) had a significant effect on the seropositivity of the dogs. Dogs older than two years had a 1.85-fold greater risk (p >0.06) of becoming infected with T. cruzi compared to younger dogs (Table 1).

Example of western blot to confirm the presence of IgG antibodies against T. cruzi in dogs positive to indirect ELISA. Lane M: molecular weight marker Biorad cat. 161–0373 All Blue 250 kD; lane 1: positive control (serum from a dog confirmed as positive); lane 2: negative control (serum from a dog confirmed as negative); lane 3; control of dog anti-IgG; lanes 4–8: samples of owned dogs in the metropolitan area of Merida, Yucatan, reactive to T. cruzi

In addition, the role of owned dogs (domiciliary dogs) as reservoirs of T. cruzi in the city of Merida was studied. Although the prevalence of T. cruzi has been widely reported in urban dogs, most of the studies were based on stray dogs from cities or villages, or a low number of owned dogs were included. A survey conducted on 148 stray dogs and 114 pet dogs in a similar city from the Yucatan Peninsula (Campeche) reports T. cruzi seroprevalences of 9.5 and 5.3 %, respectively [14]. In Costa Rica, the prevalence in pet dogs varies from 5.2 % (n = 58) to 1.6 % (n = 51) from endemic and non-endemic areas, respectively [15]. Several studies in Texas, United States, demonstrate the presence of T. cruzi in owned dogs with frequencies ranging from 12 % (n = 136 dogs) to 15 % (n = 356 dogs) [16, 17]. Other USA states report seroprevalences of 4 % (n = 301 dogs) in Oklahoma, 22 % (n = 50 dogs) in Louisiana and 6 % (n = 860 dogs) in Tennessee [18–20]. The exposure of pet dogs to the infected vector demonstrates the risk to humans living in the same households [9, 21, 22]. The variation in the prevalence in different studies may be due to the presence and abundance of the vector in each studied region; the presence of vectors depends on climatic, environmental and geographical conditions that are ideal for their survival and reproduction. The presence of the vector may be closely associated with different social and economic conditions of each region; the survival and reproduction of vectors may favored in low economic conditions [5, 14, 23].

These results indicate that the vector adapts quickly to houses, gardens and parks in the city and can spread quickly when urbanization is introduced into rural areas. The blood of dogs may be an important source of triatomine bugs [24]. The vector T. dimidiata is well established within the municipality of Merida, Yucatan [25]. Dogs can act as sentinels of domestic and peridomestic vector-mediated transmission of T. cruzi, which was demonstrated in the Chaco province in Argentina and can be used as a control group if canine infections acquired by all other routes could be excluded [4]. Results from the present study suggest that dogs from the south area of the city are at higher risk of infection. In this particular area, the socioeconomic deprivation index is higher compared to the northern area [26]. The higher frequency of infected dogs in the south may be due to the characteristics of the construction of houses: for example, when roofing is made of aluminum sheets or guano or when cracks are present in the in walls where vectors can nest [27]. Furthermore, urbanization and the rapid growth of cities into rural areas increased the risk of vector transmission to dogs and humans because of their invasion into the natural areas of the vectors. As reported in other urban cities, trypanosomatids are increasingly closer to urban centers and highly associated with human cases [9]. In the present study, despite age not being a significant factor (p <0.06), older dogs are usually at a higher risk of being in contact with the vector; this result is similar to a result previously reported [1, 2].

Conclusions

The American trypanosomiasis is present in a large proportion of dogs living in the city of Merida. This result is most likely due to the ability of vectors to adapt to the urban conditions, particularly the ideal conditions for vector nesting and multiplication found in the south of the city. Therefore, a surveillance program should be implemented and inhabitants must be educated about the risks for infection and practice vigilance in order to lower these risks for pets and humans.

Ethics committee approval

The present study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias from the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (CB-CCBA I-2014-003). In addition, dog blood samples were collected with their owners’ consent after explaining the objectives of the study.

References

Jiménez-Coello M, Poot-Cob M, Ortega-Pacheco A, Guzman-Marin E, Ramos-Ligonio A, Sauri-Arceo CH, et al. American Trypanosomiasis in dogs from an urban and rural area of Yucatan, Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8(6):755–61.

Jiménez-Coello M, Guzmán-Marin ES, Ortega-Pacheco A, Acosta-Viana KY. Serological survey of American Trypanosomiasis in dogs and their owners from an urban area of Mérida Yucatán, México. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2010;57(1–2):33–6.

Guzmán-Marín ES, Barrera-Pérez MA, Rodríguez-Félix MA, Zavala-Velázquez JE. Hábitos biológicos de Triatoma dimidiata en el Estado de Yucatán, México. Rev Biomed. 1992;3(3):125–31.

Castañera MB, Lauricella MA, Chuit R, Gürtler RE. Evaluation of dogs as sentinels of the transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi in a rural area of north-western Argentina. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1998;92(6):671–83.

Estrada-Franco JG, Bhatia V, Diaz-Albiter H, Ochoa-Garcia L, Barbabosa A, Vazquez-Chagoyan JC, et al. Human Trypanosoma cruzi infection and seropositivity in dogs, Mexico. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(4):624–30.

Gürtler RE, Cecere MC, Lauricella MA, Cardinal MV, Kitron U, Cohen JE. Domestic dogs and cats as sources of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in rural northwestern Argentina. Parasitology. 2007;134(1):69–82.

Eloy LJ, Lucheis SB. Canine trypanosomiasis: etiology of infection and implications for public health. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2009;15(4):589–611.

Jimenez-Coello M, Ortega-Pacheco A, Guzman-Marin E, Guiris-Andrade DM, Martinez-Figueroa L, Acosta-Viana KY. Stray dogs as reservoirs of the zoonotic agents Leptospira interrogans, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Aspergillus spp. in an urban area of Chiapas in southern Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10(2):135–41.

Lucheis SB, DA Silva AV, Araujo Jr JP, Langoni H, Meira DA, Marcondes-Machado J. Trypanosomatids in dogs belonging to individuals with chronic Chagas’ disease living in Botucatu town and surrounding region, São Paulo State, Brazil. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2005;11(4):492–509.

Gürtler RE, Cohen JE, Cecere MC, Chuit R. Shifting host choices of the vector of Chagas disease Triatoma infestans, in relation to the availability of hosts in houses in north-west Argentina. J Appl Ecol. 1997;34(3):699–715.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Delimitación de las zonas metropolitanas de México. Grupo Interinstitucional con base en el XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000, II Conteo de Población y Vivienda, declaratorias y programas de ordenación de zonas conurbadas y zonas metropolitanas. Mexico: 2005.

Ortega-Pacheco A, Rodríguez-Buenfil JC, Bolio-González ME, Sauri-Arceo CH, Jiménez-Coello M, Linde FC. A survey of dog populations in urban and rural areas of Yucatan, Mexico. Anthrozoös. 2007;20(3):261–74.

Teixeira MGM, Borges-Pereira J, Netizert E, Souza MLNX, Peralta JM. Development and evaluation of an enzyme linked immunotransfer blot technique for serodiagnosis of Chagas’ disease. Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;45(4):308–12.

Balan LU, Yerbes IM, Piña MA, Balmes J, Pascual A, Hernández O, et al. Higher seroprevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in dogs than in humans in an urban area of Campeche, Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11(7):843–4.

Reyes L, Silesky E, Cerdas C, Chinchilla M, Guerrero O. Presencia de anticuerpos contra Trypanosoma cruzi en perros de Costa Rica. Parasitol Latinoam. 2002;57(1–2):66–8.

Burkholder JE, Allison TC, Kelly VP. Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas) (Protozoa: Kinetoplastida) in invertebrate, reservoir, and human hosts of the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas. J Parasitol. 1980;66(2):305–11.

Shadomy SV, Waring SC, Martins-Filho OA, Oliveira RC, Chapell CL. Combined use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and flow cytometry to detect antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi in domestic canines in Texas. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(2):313–19.

Bradley KK, Bergman DK, Woods JP, Crutcher JM, Kirchhoff LV. Prevalence of American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) among dogs in Oklahoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2000;217(12):1853–7.

Nieto PD, Boughton R, Dorn PL, Steurer F, Raychaudhuri S, Esfandiari J, et al. Comparison of two immunochromatographic assays and the indirect immunofluorescence antibody test for diagnosis of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in dogs in south central Louisiana. Vet Parasitol. 2009;165(3–4):241–7.

Rowland ME, Maloney J, Cohen S, Yabsley MJ, Huang J, Kranz M, et al. Factors associated with Trypanosoma cruzi exposure among domestic canines in Tennessee. J Parasitol. 2010;96(3):547–51.

Paredes EA, Miranda JV, Torres BN, Alejandre-Aguilar R, Romero RC. Vectorial importante of triatominae bugs (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Guaymas, Mexico. Rev Latinoamer Microbiol. 2001;43(3):119–22.

Matias A, de la Riva J, Martínez E, Torrez M, Dujardin JP. Domiciliation process of Rhodnius stali (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) in Alto Beni, La Paz, Bolivia. Trop Med International Health. 2003;8(3):264–8.

Barbabosa-Pliego A, Gil PC, Hernández DO, Aparicio-Burgos JE, de Oca-Jiménez RM, Martínez-Castañeda JS, et al. Prevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs (Canis familiaris) and triatomines during 2008 in a sanitary region of the State of Mexico, Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11(2):151–6.

Mota J, Chacon JC, Gutiérrez-Cabrera AE, Sánchez-Cordero V, Wirtz RA, Ordoñez R, et al. Identification of blood meal source and infection with Trypanosoma cruzi of Chagas disease vectors using a multiplex cytochrome b polymerase chain reaction assay. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7(4):617–27.

Guzman-Tapia Y, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Dumonteil E. Urban infestation by Triatoma dimidiata in the city of Mérida, Yucatán, México. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7(4):597–606.

Gil GG, Peña YO, Pech RO. Distribución espacial de la marginación urbana en la ciudad de Mérida, Yucatán, México. Invest. Geog no.77 México abr. 2012

Medrano-Mercado N, Ugarte-Fernandez R, Butrón V, Uber-Busek S, Guerra HL, Araújo-Jorge TC. Urban transmission of Chagas disease in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103(5):423–30.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to Planned Pethood Mexico particularly Dr Antonio Rios, Nelson Miss and Jeffrey Young for their help and facilities given for the sampling of animals used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MJC and AOP conceived and designed the study. AOP and ABI collected biological samples; ABI, KAV and EGM performed serological tests. MJC and EGM performed statistical analysis. AOP and MJC drafted the manuscript and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiménez-Coello, M., Acosta-Viana, K., Guzmán-Marín, E. et al. American trypanosomiasis and associated risk factors in owned dogs from the major city of Yucatan, Mexico. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 21, 37 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40409-015-0039-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40409-015-0039-2