Abstract

Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ETP-ALL) is a rare, distinct subtype of T-ALL characterized by genomic instability, a dismal prognosis and refractoriness to standard chemotherapy. Since its first description in 2009, the expanding knowledge of its intricate biology has led to the definition of a stem cell leukemia with a combined lymphoid-myeloid potential: the perfect trick. Several studies in the last decade aimed to better characterize this new disease, but it was recognized as a distinct entity only in 2016. We review current insights into the biology of ETP-ALL and discuss the pathogenesis, genomic features and their impact on the clinical course in the precision medicine era today.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ETP-ALL) was first described in a cohort of pediatric patients as a distinct subgroup of T-ALL, based on a peculiar gene expression profile (GEP) and immunophenotypic characteristics [1]. ETP-ALL accounts for approximately 16% of childhood and 22% of adult T-ALL, and is generally associated with high genomic instability, poor outcomes and refractoriness to standard chemotherapy [2, 3]. However, recent evidence shows few differences in terms of survival and prognostic significance compared to T-ALL [4]. Since its seminal description, ETP-ALL has gained increasing interest in light of its adverse clinical features and complex biology. It is now considered as a stem cell leukemia at the crossroads of the lymphoid and myeloid fates: the perfect trick [5, 6]. This review aims to discuss current insights into the biology of ETP-ALL, to probe its complex pathogenesis, genomic features and their impact on the clinical course.

The cell of origin and leukemogenic patterns

The original pathogenic hypothesis of ETP-ALL envisaged the oncogenic transformation of normal ETPs [1]: immature thymocytes capable of migrating from the bone marrow (BM) to the thymus, retaining both the lymphoid and myeloid differentiation potential, thus indicating a direct derivation from hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [7, 8]. Coustan-Smith and colleagues identified the ETP as the cell of origin based on GEP, revealing comparable profiles between normal and leukemic cells [1]. Moreover, they demonstrated that the ETP-ALL gene expression signature resembled that of murine ETP [1]. Nevertheless, their hypothesis is still a matter of debate.

ETP-ALL may arise from slightly more differentiated T cells; in the stepwise development of thymocytes, the potential for lymphoid and myeloid differentiation is retained beyond the ETP until the CD4 and CD8 double-negative 2 (DN2) stage [8, 9]. Exceeding this concept, the sleeping beauty transposon system advanced by Berquam-Vrieze and colleagues, an approach in which transposon mutagenesis is initiated at different developmental time points along the T-cell lineage, suggested that ETP-ALL may develop from late CD4+CD8+ T cells [10]. On the other hand, detailed comparison of the global transcriptional profile of ETP-ALL with both normal HSC and leukemic myeloid stem cells revealed similar results, whereas no correlations with normal human ETPs were found [5]. These findings demonstrate that ETP-ALL is a neoplasm of a less mature hematopoietic progenitor or stem cell, that undergoes arrest at a very early maturational stage while retaining the capacity for myeloid differentiation.

To date, even if both the transcriptional and mutational landscapes have been extensively described, there is no univocal hypothesis about the leukemogenic patterns of ETP-ALL. Nevertheless, the high prevalence of mutations in genes involving cytokine receptors and RAS signalling, hematopoietic development and histone modification has been the basis of various studies [5]. Approximately 20% of pediatric ETP-ALL cases harbour activating mutations in the interleukin-7 receptor (IL7r) or the downstream Janus kinases JAK1 and JAK3 genes. It was demonstrated that Il7r mutants are capable of blocking thymocyte differentiation at the DN2 stage and inducing ETP-ALL in transplanted mice [11]; moreover, the concomitant introduction of Runx1 and Jak3 mutations in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in mice gave rise to T-ALL with the ETP phenotype [12].

Furthermore, mutations in IL7r activate STAT5, thus suggesting that activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in ETP-ALL can be independent of the presence of JAK/STAT mutations, as confirmed by further evidence [13]. This latter observation opens a therapeutic window for JAK inhibition [13] and suggests that ETP-ALL may require continual IL7r signaling for maintenance and leukemic growth [11].

Moreover, altered IL7r signaling may be involved in the maturation block of thymocytes, by regulating the expression of the oncogenic transcription factor LMO2 [13]. Experimental data showed that LMO2 and LYL1 co-expression is frequent in ETP-ALL, and is critical for the LMO2-dependent upregulation of a stem cell-like gene signature, aberrant self-renewal of thymocytes and consequent generation of T-cell leukemia [14]. The central role of IL7r was further addressed in a murine Zeb2 (a transcription factor of the zinc-finger E-box-binding family) gain of function model, demonstrating an upregulated Il7r expression in immature T and ETP-ALL cells [15].

Inactivating mutations in components of the epigenetic regulator polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), such as EZH2, SUZ12, EED, are frequently detected in ETP-ALL and are associated with aberrant RAS signalling in response to the loss of the H3K27me3 repressive histone mark. This leads to activation of gene transcription via recruitment of the bromodomain and extra terminal (BET) proteins [5, 16]. In a murine model of hematopoietic progenitors with overexpressed oncogenic mutant Nras and deleted Cdkn2a (of note this is uncommon in ETP-ALL) abrogation of either Ezh2 or Eed led to a shorter ETP-ALL latency and deregulation of growth and survival signalling [17]. Ezh2 inactivation was associated with a stem cell gene expression profile, and deregulation of cytokine expression and their receptors [18]. Moreover, abrogation of Ezh2 accentuated Ras deregulation and increased Stat3 phosphorylation, thus reinforcing the role of the JAK/STAT pathway as a therapeutic target [18]. In line with the above data, STAT3 hyperactivation was highly dependent on IL6 and IL7 stimulation [13, 18].

Concurrent mutation of EZH2 and the transcription factor RUNX1 is a relatively common event in ETP-ALL [5]; experimental data in normal ETP showed that inactivation of either of the two genes did not affect cell development, whereas inactivation of both genes resulted in expansion of the ETP pool and blocked differentiation [19]. Interestingly, even if the transcriptional profile of these mutant ETP cells was comparable to that of ETP-ALL, no signs of leukemia development were detected, indicating that further oncogenic hits are needed to complete leukemogenesis.

Coherently, in Runx1/Ezh2 double mutant mice the acquisition of FLT3 internal tandem duplications (ITD) activating mutations (a frequent event in ETP-ALL) led to leukemia development [19, 20]. Further observations in FLT3 mutated ETP-ALL lacking clonal T cell receptor (TCR) rearrangement seem to confirm that leukemic transformation takes place at the ETP level [20]. FLT3-ITD, too, provides a further molecular marker for target therapy. In the models mentioned above, different cell populations transforming into ETP-ALL were used: DN2 thymocytes, hematopoietic progenitors and ETP, respectively [11, 18, 19]. These data do not only reflect the high and complex genetic heterogeneity of this leukemic subtype but also reinforce the open debate about the cell type in which the leukemic transformation begins.

Immunophenotypic signature

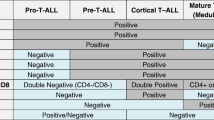

Immunophenotypic characterization is a cornerstone in the diagnosis of ETP-ALL. This typically features the expression of CD2, CD7 and cytoplasmic CD3, with at least one stem cell (CD34, CD117) and/or myeloid markers (CD13, CD33, HLA-DR, CD11b, CD65) in at least 25% of leukemic cells, together with negative or weak expression (<75%) of CD5, and the absence of CD1a and CD8 (Fig. 1) [1]. Nevertheless, the correct distinction of ETP-ALL is still a challenge, especially since no specific cytomorphological features have been observed [21].

Scoring schemas based on refined immunophenotypic features have been used to distinguish ETP-ALL from other leukemias in both pediatric and adult settings [22,23,24]. Of note, very few cases have been reported to co-express B lymphoid markers, indicating that leukemogenesis may possibly initiate at an even more immature precursor stage of ETP, retaining some degree of B lymphoid potential [25, 26].

Moreover, the stringent immunophenotypic signature of ETP-ALL has been addressed by the definition of a “near-ETP-ALL”, expressing CD5 at higher levels and a comparable gene expression profile, suggesting a slightly more mature transforming cell [27]. Interestingly, CD5 expression had been central in correctly identifying all ETP-ALL cases: to recognize ETP-ALL, the authors did not include CD5 but relied on CD7+, with CD34+ and/or CD13+/CD33+, whereas CD1, CD4, CD8 were negative [28]. This immunophenotypic signature allowed the identification of cases with ETP-ALL GEP, with 94% specificity [28]. All these observations point out, on one hand, the importance of immunophenotypic characterization as a practical tool to correctly delineate ETP-ALL cases; on the other, the cited exceptions to the typical signature may reflect the fine line separating one leukemic subtype from another, emphasizing the role of GEP and genomics in the characterization of biologically similar diseases.

Chromosomal aberrations

No clear association with specific chromosomal abnormalities can be found in ETP-ALL. Available data from various studies mirror the high genomic instability of the disease. Overall, ETP-ALL is reported to have a higher likelihood of harbouring cytogenetic lesions than T-ALL (Table 1); a slightly higher frequency of deletion 13q was reported [1, 3]. A translocation t(2;14)(q22;q32) has been described and associated with the deregulation of ZEB2 expression, suggesting its possible role in leukemogenesis [15]. Recently, a study on acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage showed the recurrence of 14q32 rearrangements resulting in the activation of BCL11B, co-occurring with FLT3, DNMT3A, TET2 and WT1 variants. GEP identified a specific expression signature related to BCL11B activation with significant downregulation of its targets, providing a novel biomarker for a new entity among immature acute leukemias [29].

Apart from this, ETP-ALL exhibits a lower frequency of classic recurrent rearrangements (i.e., LMO1/2, TLX1, TLX3, STIL) associated with T-ALL, confirming its distinct nature [4]. Other studies have reported a consistent percentage of KMT2A rearrangements, while the frequency of TCR locus gene rearrangements seems comparable to that of T-ALL [4, 30]. A whole-genome sequencing analysis further confirmed and refined these findings, demonstrating multiple complex rearrangements in isolated cases and a high prevalence of breakpoints in coding genes with a key role in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis (i.e., MLH3 and RUNX1) [5]. This latter may result in loss of function of the involved genes or occur as a part of complex translocations resulting in the formation of novel chimeric fusion proteins [5]. In the same cohort, the occurrence of deletions of chromosome 9 encompassing the CDKN2A/B tumour suppressor genes was less frequent as compared to non-ETP-ALL [5]. Furthermore, frequent copy number variation (CNV) events (both gain and loss of genomic material) can contribute to determining the high genomic instability widely described in ETP-ALL [1].

Mutational landscape

A comprehensive genomic analysis of pediatric ETP-ALL cases described a highly heterogeneous mutational landscape and failed to identify a unifying genetic alteration [5]. Nevertheless, differences between ETP-ALL and T-ALL are remarkable (Table 1) [31]. ETP-ALL was shown to have enriched mutations in three pathways: loss of function alterations in genes regulating hematopoietic development (i.e., RUNX1, IKZF1, ETV6, GATA3 and EP300); activating mutations driving RAS and cytokine receptor/JAK-STAT signalling (i.e., BRAF, FLT3, IGFR1, JAK1, JAK3, KRAS, NRAS and IL7r); inactivating mutations in histone-modifying genes (i.e., EED, SUZ12, EZH2). Furthermore, other genes with an unknown role in tumorigenesis and lymphoid development, such as DNM2, ECT2 and RELN, were frequently mutated [5].

Notably, genes with an established role in both myeloid and B lymphoid malignancies, such as RUNX1, ETV6 and IKZF1, had never before been associated with T-ALL forms. Moreover, mutations in the pathways mentioned above are frequently found in AML [32], emphasizing the “two-faced” nature of ETP-ALL (Fig. 2).

Subsequent studies in adult ETP-ALL cases further refined the scenario [33]. In detail, compared with non-ETP-ALL cases, ETP-ALL showed a lower frequency of mutations in genes commonly involved in the pathogenesis of ALL, namely NOTCH1 and FBXW7 [33]. Conversely, a high rate (35%) of FLT3 mutations was reported, tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) alterations being slightly more prevalent. This is in line with experimental data in mice showing the development of lymphoid diseases upon transplantation of Flt3-TKD BM cells [34]. Furthermore, cases harbouring a FLT3 mutation exhibited distinct clinical features compared with wild-type (wt) FLT3 ETP-ALL and, interestingly, a slightly different immunophenotype with a constant expression of CD117, CD34, CD13 and CD2 [33]. Extended characterization of FLT3 mutated ETP-ALL marked a distinct GEP with a higher expression of WT1 and downregulated expression of GATA3 and IGFBP7 genes as compared to FLT3-wt ETP-ALL [20].

Moreover, TCR rearrangements and NOTCH1 mutations were frequently lacking in these patients; together with the low GATA3 expression, these data suggest that the leukemic transformation in FLT3 mutated ETP-ALL might occur at a stem cell pluripotent stage, reflecting a possibly even more immature nature of this ETP-ALL subgroup [20]. Interestingly, in the first genomic characterization of ETP-ALL in pediatric patients, mutations in FLT3 and the PRC2 complex components were mutually exclusive [5]. This information may further support a different pathogenesis for FLT3 mutated ETP-ALL. Moreover, the high frequency of FLT3 mutations in this pathological context is of great clinical interest, given the reported therapeutic efficacy of tested tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [20].

A subsequent whole exome sequencing analysis provided further insights into the mutational landscape of adult ETP-ALL [6]. Aside from the detection of mutations in genes involved in both T-ALL (i.e., ETV6, NOTCH1, DNM2) and myeloid malignancies (i.e., NRAS, JAK1, FLT3), recurrent mutations in two genes, DNMT3A and FAT3, were reported. Notably, none of these had previously been associated with ETP-ALL. Novel mutations in FAT1 and MLL2 were also detected [6]. Strikingly, over 60% of the ETP-ALL cases exhibited a mutation in one of these three genes: FLT3, DNMT3A, NOTCH1, again reflecting the lymphoid-myeloid potential of the disease (Fig. 2) [6]. To further emphasize this concept, we underline that DNMT3A mutations in adult ETP-ALL, present with a similar frequency to that in AML, were located at the same hotspot and were seen in conjunction with mutations in other epigenetic regulators, thus strongly resembling AML cases [6]. Moreover, an age-dependent occurrence of specific mutations was observed: while DNMT3A mutations occurred mainly in older patients, inactivation of the PRC2 complex components was significantly less frequent than in pediatric patients [5, 6]. These observations may further suggest that, like in other hematological malignancies, in adult patients ETP-ALL could arise in the context of age-related clonal hematopoiesis [35, 36]. Nevertheless, there is evidence that a considerable proportion of adult early immature T-ALLs, not fulfilling the immunophenotypic criteria for ETP-ALL, shows mutations in myeloid related oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes (such as IDH1, IDH2, DNMT3A, FLT3, ETV6 and NRAS), while exhibiting a lower prevalence of typical T-ALL genetic alterations (such as mutations in the NOTCH1 and FBXW7 genes). This circumstance stresses the overlapping features of ETP-ALL and immature T-ALL [37].

Lastly, the fascinating genomic scenario of ETP-ALL and the need to identify other potential therapeutic targets prompted the creation of a computational model aiming to identify characteristics associated with the mutational profile of ETP-ALL compared to T-ALL cases [38]. Intriguingly, a high frequency of deletion of nucleophosmin-1 (NPM1), commonly mutated in AML, was reported, expanding the spectrum of genetic abnormalities shared between myeloid malignancies and ETP-ALL [39, 40].

GEP

As mentioned above, the first GEP of ETP-ALL in pediatric patients resembled that of murine ETP [1]. Moreover, compared to T-ALL, the identified ETP-ALL cases exhibited a slightly higher expression of oncogenic transcription factors associated with an immature thymocyte phenotype, namely LMO1, LYL1 and ERG [1]. These findings were subsequently refined, revealing a global transcriptional profile similar to that of HSCs and early myeloid progenitors [5]. Analysis of the GEP pathway demonstrated an enrichment of genes mediating the JAK-STAT pathway but no enrichment of T-cell receptor signalling genes (Fig. 2) [5]. Furthermore, reconstruction of the transcriptional network of ETP-ALL identified 30 gene networks (‘regulons’) mastered by RUNX1 and IKZF1 [5]; this may indirectly reflect the lymphoid-myeloid potential of the transforming cell. These data are in line with previous observations associating the mutational landscape of ETP-ALL with that of AML.

GEP performed in adult ETP-ALL added further evidence of the “crossover” potential of ETP-ALL. Genes (BAALC, IGFBP7) associated with a stem cell signature and adverse outcome in T-ALL, and typically expressed in myeloid leukemia (WT1, MN1), are highly overexpressed in ETP-ALL (Fig. 2) [33]. Moreover, low expression of the transcription factor GATA3 in a cohort of adult ETP-ALL cases was correlated with enrichment of myeloid/lymphoid progenitor and granulocyte/monocyte progenitor genes, while T cell-specific signatures were downregulated, suggesting a GATA3 role in the selection of a more immature leukemia-initiating cell [41]. In line with this concept, inactivating mutations of GATA3 are reported as frequent events in pediatric ETP-ALL [5].

Interestingly, experimental evidence shows that the expression of BCL-2 is higher in ETP-ALL than in more mature T-ALL, thus showing resemblances to AML, and offering a druggable therapeutic target [42, 43]. In this well-defined transcriptional profile context, it is noteworthy that cross-examination of gene sets associated with ETP-ALL [1] and immature T-ALL [28, 44,45,46] evinces a high degree of relation, indicating a biological link that exceeds the stringent immunophenotypic criteria.

Discussion

First described in 2009, ETP-ALL was included as a provisional entity only in the 2016 revision of the “WHO classification of tumours of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues” [47], recognizing its distinct nature. Intriguingly, over the years, its characterization has revealed a fascinating scenario of biological heterogeneity and ambiguity, which places ETP-ALL at the intersection of the lymphoid and myeloid fate, going beyond the well-defined immunophenotypic criteria required for diagnosis [1].

The recognition of genomic features has allowed the definition of both mutational and transcriptional landscapes, suggesting that ETP-ALL may arise from a very early immature thymocyte progenitor with a stem cell-like transcriptional profile, that retains both a lymphoid and myeloid potential [5]. However, the hypothesis regarding the cell of origin and its leukemogenic pathways is still debated. It should be noted that comparison of GEP analyses of ETP-ALL and immature T-ALL has, on one hand, revealed overlapping features, suggesting the definition of a “near-ETP-ALL” entity presenting with only slight immunophenotypic differences, mainly referred to the expression of CD5. On the other hand, it further confirmed that the origin of ETP-ALL is a T cell progenitor [1]. Nevertheless, it is still unclear at which stage of early cellular differentiation the leukemic transformation occurs. As previously reported, in thymocyte differentiation, the myeloid potential is preserved until the DN2 stage [8, 9]. Notably, the observation of cases of ETP-ALL expressing B lymphoid markers raised the idea that this leukemia may arise from an earlier than ETP progenitor, the so-called “thymic seeding progenitor”, “common lymphoid progenitor”, or “lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor” [25]. Various studies have addressed this issue, with conflicting results [26, 48, 49]. Recent evidence investigating the 3D chromosomal structures of T-ALL demonstrates that global 3D genome architecture and its alterations may reveal differences between normal T cells, T-ALL and ETP-ALL; in this context, T-ALL and ETP-ALL are described as different “frozen stages” of T-cell development with different gene expression profiles associated with 3D genome alterations [55, 56].

Furthermore, there is evidence that even ETPs might present B lymphoid markers [50, 51]. To date, the debate is still open, and we cannot draw clear conclusions. In line with this uncertainty, consistent differences have been described in the mutational landscape of pediatric and adult ETP-ALL. One such observation regards the mutual exclusivity of FLT3 mutations and PRC2 inactivation, the former being more common in adult patients and the latter in pediatric cases [5, 20, 33]. This finding may offer a further biological point of interest: is adult ETP-ALL closer to myeloid malignancies than T-ALL? Conversely, is pediatric ETP-ALL closer to T-ALL than myeloid malignancies? The age-dependent occurrence of DNMT3A mutations, and the computational model revealing a particular frequency of NPM1 mutation in adult ETP-ALL cases, seem to emphasize this open question [40]. Considering all these premises, the clinical aggressiveness and poor outcomes historically attributed to ETP-ALL should come as no surprise, as they may reflect an inability to target its highly heterogeneous and ever-expanding spectrum of genomic features [1, 3, 52]. The first therapeutic approaches, based on standard chemotherapy regimens in ALL, showed dismal responses and short relapse-free survival [1]. The introduction of pegylated asparaginase in the induction schemes and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation improved the prognosis [3, 22]. Nevertheless, various studies demonstrated no differences in event-free survival and overall survival between ETP-ALL and T-ALL [22, 53]. Notably, based on the aforementioned genomic findings, several targeted therapies are being developed for ETP-ALL (Table 2). The JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, the anti-BCL2 venetoclax, multikinase inhibitors targeting FLT3 mutations, BET inhibitors, novel immunotherapies (such as CAR-T, CAR-NK and both monoclonal antibodies and immunoconjugates targeting CD38, CD33 and CD123), are being tested alone or in combination with standard chemotherapy in both newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory ETP-ALL [13, 19, 20, 52, 54].

Conclusions

The progressive adoption of ever more specific therapeutic approaches is improving the outcome of ETP-ALL patients, underlining the importance of delving more deeply into the biology of the disease. All these observations explain the need for further studies aiming to better characterize the clinical-biological features of ETP-ALL in both pediatric and adult patients. It remains to be seen if, in the precision medicine era, the potential of new generation technologies will allow the secrets of the perfect trick to be unveiled.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ETP-ALL:

-

early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- GEP:

-

gene expression profile

- BM:

-

bone marrow

- HSCs:

-

hematopoietic stem cells

- DN2:

-

double-negative 2

- PRC2:

-

polycomb repressive complex 2

- BET:

-

bromodomain and extra terminal

- ITD:

-

internal tandem duplication

- TCR:

-

T cell receptor

- TKD:

-

tyrosine kinase domain

- TKIs:

-

tyrosine kinase inhibitors

References

Coustan-Smith E, Mullighan CG, Onciu M, Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Pei D, et al. Early T-cell precursor leukaemia: a subtype of very high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:147–56.

Mao J, Xue L, Wang H, Zhu Y, Wang J, Zhao L. A new treatment strategy for early t-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:3795–802.

Jain N, Lamb A V., O’Brien S, Ravandi F, Konopleva M, Jabbour E, et al. Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (ETP-ALL/LBL) in adolescents and adults: A high-risk subtype. Blood. 2016;127:1863–9.

Patrick K, Wade R, Goulden N, Mitchell C, Moorman A V., Rowntree C, et al. Outcome for children and young people with Early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia treated on a contemporary protocol, UKALL 2003. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:421–4.

Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, Wu G, Heatley SL, Payne-Turner D, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature [Internet]. Nature; 2012 [cited 2021 Feb 1];481:157–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22237106/

Neumann M, Heesch S, Schlee C, Schwartz S, Gökbuget N, Hoelzer D, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in adult ETP-ALL reveals a high rate of DNMT3A mutations. Blood. 2013;121:4749–52.

Bell JJ, Bhandoola A. The earliest thymic progenitors for T cells possess myeloid lineage potential. Nature. 2008;452:764–7.

Wada H, Masuda K, Satoh R, Kakugawa K, Ikawa T, Katsura Y, et al. Adult T-cell progenitors retain myeloid potential. Nature. 2008;452:768–72.

Yui MA, Feng N, Rothenberg E V. Fine-Scale Staging of T Cell Lineage Commitment in Adult Mouse Thymus. 2021;

Berquam-Vrieze KE, Nannapaneni K, Brett BT, Holmfeldt L, Jing M, Zagorodna O, et al. Cell of origin strongly influences genetic selection in a mouse model of T-ALL. Blood. 2011;118:4646–56.

Treanor LM, Zhou S, Janke L, Churchman ML, Ma Z, Lu T, et al. Interleukin-7 receptor mutants initiate early t cell precursor leukemia in murine thymocyte progenitors with multipotent potential. J Exp Med. 2014;211:701–13.

Li Y, Yang W, Devidas M, Winter SS, Kesserwan C, Yang W, et al. Germline RUNX1 variation and predisposition to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(17):e147898.

Maude SL, Dolai S, Delgado-Martin C, Vincent T, Robbins A, Selvanathan A, et al. Efficacy of JAK/STAT pathway inhibition in murine xenograft models of early T-cell precursor (ETP) acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:1759–67.

McCormack MP, Shields BJ, Jackson JT, Nasa C, Shi W, Slater NJ, et al. Requirement for Lyl1 in a model of Lmo2-driven early T-cell precursor ALL. Blood. 2013;122:2093–103.

Goossens S, Radaelli E, Blanchet O, Durinck K, Van Der Meulen J, Peirs S, et al. ZEB2 drives immature T-cell lymphoblastic leukaemia development via enhanced tumour-initiating potential and IL-7 receptor signalling. Nat Commun. 2015;6.

Booth CAG, Barkas N, Neo WH, Boukarabila H, Soilleux EJ, Giotopoulos G, et al. Ezh2 and Runx1 Mutations Collaborate to Initiate Lympho-Myeloid Leukemia in Early Thymic Progenitors. Cancer Cell [Internet]. Elsevier Inc.; 2018;33:274-291.e8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2018.01.006

Danis E, Yamauchi T, Echanique K, Zhang X, Haladyna JN, Riedel SS, et al. Ezh2 Controls an Early Hematopoietic Program and Growth and Survival Signaling in Early T Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cell Rep [Internet]. The Authors; 2016;14:1953–65. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.064

Danis E, Yamauchi T, Echanique K, Zhang X, Haladyna JN, Riedel SS, et al. Ezh2 Controls an Early Hematopoietic Program and Growth and Survival Signaling in Early T Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cell Rep. The Authors; 2016;14:1953–65.

Booth CAG, Barkas N, Neo WH, Boukarabila H, Soilleux EJ, Giotopoulos G, et al. Ezh2 and Runx1 Mutations Collaborate to Initiate Lympho-Myeloid Leukemia in Early Thymic Progenitors. Cancer Cell. Elsevier Inc.; 2018;33:274-291.e8.

Neumann M, Coskun E, Fransecky L, Mochmann LH, Bartram I, Farhadi Sartangi N, et al. FLT3 Mutations in Early T-Cell Precursor ALL Characterize a Stem Cell Like Leukemia and Imply the Clinical Use of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. PLoS One. 2013;8.

Wang P, Peng X, Deng X, Gao L, Zhang X, Feng Y. Diagnostic challenges in T-lymphoblastic lymphoma, early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia or mixed phenotype acute leukemia: A case report. Med (United States). 2018;97:0–4.

Inukai T, Kiyokawa N, Campana D, Coustan-Smith E, Kikuchi A, Kobayashi M, et al. Clinical significance of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Results of the Tokyo Children’s Cancer Study Group Study L99-15. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:358–65.

Chopra A, Bakhshi S, Pramanik SK, Pandey RM, Singh S, Gajendra S, et al. Immunophenotypic analysis of T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia. A CD5-based ETP-ALL perspective of non-ETP T-ALL. Eur J Haematol. 2014;92:211–8.

Khogeer H, Rahman H, Jain N, Angelova EA, Yang H, Quesada A, et al. Early T precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma shows differential immunophenotypic characteristics including frequent CD33 expression and in vitro response to targeted CD33 therapy. Br J Haematol. 2019;186:538–48.

Garg S, Gupta SK, Bakhshi S, Mallick S, Kumar L. ETP-ALL with aberrant B marker expression: Case series and a brief review of literature. Int J Lab Hematol. 2019;41:e32–7.

Bhandoola A, von Boehmer H, Petrie HT, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Commitment and Developmental Potential of Extrathymic and Intrathymic T Cell Precursors: Plenty to Choose from. Immunity. 2007;26:678–89.

Morita K, Jain N, Kantarjian H, Takahashi K, Fang H, Konopleva M, et al. Outcome of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma: Focus on near-ETP phenotype and differential impact of nelarabine. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:589–98.

Zuurbier L, Gutierrez A, Mullighan CG, Canté-Barrett K, Gevaert AO, De Rooi J, et al. Immature MEF2C-dysregulated T-cell leukemia patients have an early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia gene signature and typically have non-rearranged t-cell receptors. Haematologica. 2014;99:94–102.

Di Giacomo D, La Starza R, Gorello P, Pellanera F, Kalender Atak Z, De Keersmaecker K, et al. 14q32 rearrangements deregulating BCL11B mark a distinct subgroup of T and myeloid immature acute leukemia. Blood. 2021 19:blood.2020010510.

Allen A, Sireci A, Colovai A, Pinkney K, Sulis M, Bhagat G, et al. Early T-cell precursor leukemia/lymphoma in adults and children. Leuk Res [Internet]. Elsevier Ltd; 2013;37:1027–34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2013.06.010

Liu Y, Easton J, Shao Y, Maciaszek J, Wang Z, Wilkinson MR, et al. The genomic landscape of pediatric and young adult T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. Nature Publishing Group; 2017;49:1211–8.

Hou HA, Tien HF. Genomic landscape in acute myeloid leukemia and its implications in risk classification and targeted therapies. J Biomed Sci. Journal of Biomedical Science; 2020;27:1–13.

Neumann M, Heesch S, Gökbuget N, Schwartz S, Schlee C, Benlasfer O, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of early T-cell precursor leukemia: A high-risk subgroup in adult T-ALL with a high frequency of FLT3 mutations. Blood Cancer J [Internet]. Blood Cancer J; 2012;2. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22829239/

Grundler R, Miething C, Thiede C, Peschel C, Duyster J. FLT3 ITD and FLT3 Tyrosine Kinase Domain Mutants Induce Different Phenotypes in a Murine Bone Marrow Transplant Model. Blood [Internet]. American Society of Hematology; 2004;104:3371–3371. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V104.11.3371.3371

Knoechel B, Bhatt A, Pan L, Pedamallu CS, Severson E, Gutierrez A, et al. Complete hematologic response of early T-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia to the γ-secretase inhibitor BMS-906024: genetic and epigenetic findings in an outlier case. Mol Case Stud. 2015;1:a000539.

Midic D, Rinke J, Perner F, Müller V, Hinze A, Pester F, et al. Prevalence and dynamics of clonal hematopoiesis caused by leukemia-associated mutations in elderly individuals without hematologic disorders. Leukemia [Internet]. Springer US; 2020;34:2198–205. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0869-y

Vlierberghe P Van, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Perez-Garcia A, Haydu JE, Rigo I, Hadler M, et al. ETV6 mutations in early immature human T cell leukemias. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2571–9.

Kumar A, Drusbosky LM, Meacham A, Turcotte M, Bhargav P, Vasista S, et al. Computational modeling of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ETP-ALL) to identify personalized therapy using genomics. Leuk Res [Internet]. Elsevier; 2019;78:3–11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2019.01.003

Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–47.

Kumar A, Drusbosky LM, Meacham A, Turcotte M, Bhargav P, Vasista S, et al. Computational modeling of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ETP-ALL) to identify personalized therapy using genomics. Leuk Res. Elsevier; 2019;78:3–11.

Fransecky L, Neumann M, Heesch S, Schlee C, Ortiz-Tanchez J, Heller S, et al. Silencing of GATA3 defines a novel stem cell-like subgroup of ETP-ALL. J Hematol Oncol. Journal of Hematology & Oncology; 2016;9:1–12.

Ni Chonghaile T, Roderick JE, Glenfield C, Ryan J, Sallan SE, Silverman LB, et al. Maturation stage of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia determines BCL-2 versus BCL-XL dependence and sensitivity to ABT-199. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1074–87.

Peirs S, Matthijssens F, Goossens S, Van De Walle I, Ruggero K, De Bock CE, et al. ABT-199 mediated inhibition of BCL-2 as a novel therapeutic strategy in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:3738–47.

Soulier J, Clappier E, Cayuela JM, Regnault A, García-Peydró M, Dombret H, et al. HOXA genes are included in genetic and biologic networks defining human acute T-cell leukemia (T-ALL). Blood. 2005;106:274–86.

Homminga I, Pieters R, Langerak AW, de Rooi JJ, Stubbs A, Verstegen M, et al. Integrated Transcript and Genome Analyses Reveal NKX2-1 and MEF2C as Potential Oncogenes in T Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell [Internet]. Elsevier Inc.; 2011;19:484–97. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.008

Ferrando AA, Neuberg DS, Staunton J, Loh ML, Huard C, Raimondi SC, et al. Gene expression signatures define novel oncogenic pathways in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:75–87.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–405.

Porritt HE, Rumfelt LL, Tabrizifard S, Schmitt TM, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC, Petrie HT. Heterogeneity among DN1 prothymocytes reveals multiple progenitors with different capacities to generate T cell and non-T cell lineages. Immunity. 2004;20:735–45.

Balciunaite G, Ceredig R, Rolihk AG. The earliest subpopulation of mouse thymocytes contains potent T, significant macrophage, and natural killer cell but no B-lymphocyte potential. Blood. 2005;105:1930–6.

Benz C, Bleul CC. A multipotent precursor in the thymus maps to the branching point of the T versus B lineage decision. J Exp Med. 2005;202:21–31.

Luc S, Luis TC, Boukarabila H, Macaulay IC, Buza- N. Europe PMC Funders Group The Earliest Thymic T Cell Progenitors Sustain B Cell and Myeloid Lineage Potentials. 2012;13:412–9.

Castaneda Puglianini O, Papadantonakis N. Early precursor T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: current paradigms and evolving concepts. Ther Adv Hematol. 2020;11:204062072092947.

Allen A, Sireci A, Colovai A, Pinkney K, Sulis M, Bhagat G, et al. Early T-cell precursor leukemia/lymphoma in adults and children. Leuk Res. Elsevier Ltd; 2013;37:1027–34.

Lato MW, Przysucha A, Grosman S, Zawitkowska J, Lejman M. The new therapeutic strategies in pediatric t-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22.

Kloetgen A, Thandapani P, Ntziachristos P, Ghebrechristos Y, Nomikou S, Lazaris C, Chen X, Hu H, Bakogianni S, Wang J, Fu Y, Boccalatte F, Zhong H, Paietta E, Trimarchi T, Zhu Y, Van Vlierberghe P, Inghirami GG, Lionnet T, Aifantis I, Tsirigos A. Three-dimensional chromatin landscapes in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet. 2020 52(4):388–400.

Yang L, Chen F, Zhu H, Chen Y, Dong B, Shi M, Wang W, Jiang Q, Zhang L, Huang X, Zhang MQ, Wu H. 3D genome alterations associated with dysregulated HOXA13 expression in high-risk T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Commun. 2021 Jun 17;12(1):3708.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by “Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie (AIL)-BARI”.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.T., C.C., F.A.; writing–original draft preparation: F.T., C.C., F.A.; writing–review and editing: F.T., C.C., L.A., A.Z., G.S., P.M., F.A.; supervision: F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tarantini, F., Cumbo, C., Anelli, L. et al. Inside the biology of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the perfect trick. Biomark Res 9, 89 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-021-00347-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-021-00347-z