Abstract

Background

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is an antimetabolite that interferes with DNA synthesis and has been widely used as a chemotherapeutic drug in various types of cancers. However, the development of drug resistance greatly limits its application. Overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in many types of cancer is responsible for the reduction of the cellular uptake of various anticancer drugs causing multidrug resistance (MDR), the major obstacle in cancer chemotherapy. Recently, we have obtained a novel synthetic 5-FU analog, U-332 [(R)-3-(4-bromophenyl)-1-ethyl-5-methylidene-6-phenyldihydrouracil], combining a uracil skeleton with an exo-cyclic methylidene group. U-332 was highly cytotoxic for HL-60 cells and showed similar cytotoxicity in the 5-FU resistant subclone (HL-60/5FU), in which this analog almost completely abolished expression of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, multidrug resistance associate protein 1 (ABCC1). The expression of ABC transporters is usually correlated with NF-κB activation. The aim of this study was to determine the level of NF-κB subunits in the resistant HL-60/5-FU cells and to evaluate the potential of U-332 to inhibit activation of NF-κB family members in this cell line.

Methods

Anti-proliferative activity of compound U-332 was assessed by the MTT assay. In order to disclose the mechanism of U-332 cytotoxicity, quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the NF-κB family genes, c-Rel, RelA, RelB, NF-κB1, and NF-κB2, was investigated. The ability of U-332 to reduce the activity of NF-κB members was studied by ELISA test.

Results

In this report it was demonstrated, using RT-PCR and ELISA assay, that members of the NF-κB family c-Rel, RelA, RelB, NF-κB1, and NF-κB2 were all overexpressed in the 5-FU-resistant HL-60/5FU cells and that U-332 potently reduced the activity of c-Rel, RelA and NF-κB1 subunits in this cell line.

Conclusions

This finding indicates that c-Rel, RelA and NF-κB1 subunits are responsible for the resistance of HL-60/5FU cells to 5-FU and that U-332 is able to reverse this resistance. U-332 can be viewed as an important lead compound in the search for novel drug candidates that would not cause multidrug resistance in cancer cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The incidence of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and heterogeneous clonal disorders of hematopoietic progenitor cells are increasing worldwide [1]. There are several therapies which are offered for patients with AML but survival after relapse remains poor, necessitating the search for novel chemotherapeutic candidates. At present, the toxic effect of chemotherapy and the occurrence of secondary malignancies associated with AML are the major drawbacks in the pharmacotherapy of AML. Moreover, the frequent acquisition of multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype is the additional serious problem in the treatment of AML patients. Neoplastic cells are able to develop many different mechanisms of MDR, such as DNA mutations, cell metabolic changes and very often, overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and activation of the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) [2,3,4].

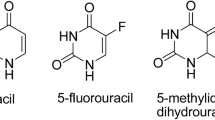

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) was the first synthetic fluoropyrimidine analog that showed pharmacological activity. At the molecular level, 5-FU is an antineoplastic antimetabolite that interferes with DNA synthesis by blocking the thymidylate synthase-catalyzed conversion of deoxyuridylic acid to thymidylic acid [5]. In numerous cancer cells, 5-FU inducesh67hu apoptosis and cell cycle arrest and inhibits proliferation [6,7,8]. Since its first synthesis in 1957 [9] 5-FU has been widely used as a chemotherapeutic drug in various types of cancer [10]. However, its application is now limited due to the serious side-effects and the development of resistance [11]. Numerous modifications of 5-FU have been proposed so far, and new analogs modified at position 1, such as tegafur, carmofur and floxuridine (Fig. 1) are now replacing 5-FU in clinical practice [12].

Though new anticancer agents continue to be discovered, the problem of resistance is still a major obstacle in obtaining efficient drug candidates. Among various mechanisms that can be developed by neoplastic cells in order to escape medical intervention, overexpression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters is the one well documented [3, 4]. The ABC transporter family are transmembrane proteins involved in the normal physiological process but also in the mechanism of drug resistance in cancer cells. The ABC proteins function as efflux pumps that can transport drugs out of the cells in the ATP energy-dependent mechanism, reducing their intracellular concentration [13]. The best known transporters that were shown to reduce the cellular uptake of anticancer drugs, including 5-FU, are P-glycoprotein (ABCB1), multidrug resistance associate protein 1 (ABCC1) and breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) [14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

The mechanism of ABC transporter regulation is still not fully understood. Recently, many transcription factor-binding sequences, such as those for p53, AP-1 and, very often, for NF-κB have been identified in the promoter region of the ABCB1 gene [21,22,23].

NF-κB consists of a family of five proteins, p65 (RelA), RelB, c-Rel, p105/p50 (NF-κB1), and p100/52 (NF-κB2) that may form different transcriptionally active homo- and heterodimeric complexes [24] (Fig. 2). The most important subunit of the NF-κB family is RelA/p65, which is phosphorylated in the posttranslational activation mechanism [24, 25]. RelB is the only NF-κB subunit that does not form homodimers and can trigger a potent transcriptional activation only when coupled to p50 or p52. The c-Rel plays an essential role in the regulation of T-cell-mediated immunity [26]. NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 are the precursor forms of p50 and p52, respectively [27].

The members of NF-κB family. The Rel homology domain is characteristic for all memb ers the NF-κB family, while the ankyrin repeats only for the NF-κB inhibitors and the NF-κB precursors of p50 and p52 subunits (p100, p105). The transactivation domain is a C-terminal non-homologous domain that is important for NF-κB-mediated gene transactivation. For activation of transactivation domain, RelB requires an amino-terminal leucine zipper region

Various chemotherapeutic drugs, including 5-FU, were shown to activate NF-κB. The members of the NF-κB family can be activated in several ways. In the classical NF-κB pathway, various cellular receptors, such as tumor necrosis factor receptors (TNFRs), are activated. Then, the inhibitory IκB proteins, that form dimmers with NF-κB subunits, are phosphorylated at two specific serine residues. The IκB activation leads to disintegration of the NF-κB complexes. RelA- and c-Rel-containing dimers translocate to the nucleus where they regulate over 100 transcription targets. The genes whose expression is regulated by NF-κB play an important role in immune/stress responses, apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation and development [28, 29].

Continuing the search for novel compounds with anticancer properties, we have recently described a series of uracil analogs, combining uracil skeleton with an exo-cyclic methylidene group conjugated with a carbonyl function [30]. These analogs were all highly cytotoxic against leukemia HL-60 cell line. The most potent analog of the series, (R)-3-(4-bromophenyl)-1-ethyl-5-methylidene-6-phenyldihydrouracil, designated U-332 (Fig. 1), caused in HL-60 cells excessive DNA damage which led to the cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase and apoptosis. To determine the activity of U-332 in the resistant cells, we recently selected a 5-FU resistant subclone (HL-60/5FU) of HL-60 cell line by the conventional method of the continuous exposure of the cells to 5-FU up to 0.08 mmol/L concentration [31]. HL-60/5FU cells exhibited a 6-fold enhanced resistance to 5-FU as compared with HL-60 cells. RT-PCR and ELISA assay showed significant overexpression of MDR-related ABC transporters, ABCB1, ABCG2 but especially ABCC1 in the HL-60/5FU, as compared with the parental cell line. U-332 almost completely abolished ABCC1 expression in the resistant HL-60/5FU cells disturbing therefore drug efflux [31].

The aim of this study was to determine the level of NF-κB subunits in the resistant HL-60/5-FU cell line and to evaluate the potential of a novel uracil analog U-332 to inhibit activation of NF-κB family members in this cell line. For comparison, bengamide (BGD) [32], a potent inhibitor of NF-κB activation was included in the research.

Methods

Chemistry

Synthesis of (R)-3-(4-bromophenyl)-1-ethyl-5-methylidene-6-phenyldihydrouracil (U-332) was performed using Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons methodology, as described elsewhere [33]. Starting 3-(4-bromophenyl)-5-diethoxyphosphoryl-1-ethyluracil 1 was transformed into 3-(4-bromophenyl)-5-dichlorophosphoryl-1-ethyluracil 2 which was next reacted with (R)-1-phenylethylamine to yield (R,R)-3-(4-bromophenyl)-5-di (1-phenylethylamino)phosphoryl-1-ethyluracil (R,R)-3. This compound was used as a Michael acceptor in the reaction with phenylmagnesium chloride and obtained trans-adduct (R,R)-4 was separated and purified. Absolute configuration of this compound was confirmed by single crystal X-ray technique. When (R,R)-4 was applied in Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of formaldehyde, (R)-3-(4-bromophenyl)-1-ethyl-5-methylidene-6-phenyldihydrouracil U-332 was obtained as pure enantiomer (ee > 99%).

Materials

BGD was obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). U-332 and BGD were dissolved in DMSO and diluted in culture medium to obtain less than 0.1% DMSO v/v concentration.

Cell culture

The human leukemia cell line, HL-60 was purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC) and was cultured in RPMI 1640 plus GlutaMax I medium (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 μg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin).

5-FU-resistant HL-60 cell line was obtained by a long-time exposure of HL-60 cells to increasing 5-FU concentrations (0.01–10 mg/L). The process was repeated until the cells were able to tolerate up to 10 mg/L of 5-FU. The detailed description of this procedure was given elsewhere [31].

Metabolic activity - MTT assay

The determination of anti-proliferative activity of U-332 and BGD was performed by the MTT assay, according to the Mosmann method, as described elsewhere [34].

Quantitative real-time PCR assay

The expression of NF-κB genes was analyzed by real-time PCR (RT-PCR). Briefly, the HL-60 and HL-60/5FU cells were seeded on the 6-well plates at the optimal cell density (3.0 × 105 cells/well in 3 mL of culture media), treated with the tested compounds at IC50 concentration each and left to grow for 24 h. Total RNA was directly extracted from cultured cells, using the Total RNA Mini Kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland) while Transcriba Kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland) was used for cDNA synthesis, according to the manufacturer’s procedure.

Amplification of cDNA was performed using Real-Time 2x-PCR SYBR Master Mix (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland) and gene specific primers (RelA, RelB, NF-κB1, NF-κB2 and c-Rel) (Table 1) in Stratagene MX3005P QPCR System (Agilent Technologies, Inc. Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was used as an internal reference gene for normalization of qPCR results. The gene expression levels were determined by the 2-∆∆CT method [35].

Determination of NF-κB subunit activity by ELISA-based method

The activity of NF-κB family members (p50, p52, p65, c-Rel, RelB) was analyzed in the cellular protein extracts (10 μg) by the ELISA-based method using NF-κB (p50, p52, p65, c-Rel, RelB) Transcription Factor Assay Kit (ABCAM). Briefly, HL-60 and HL-60/5FUres cells were seeded in triplicate into 6-well plates at the optimal cell density (4.5 × 105 cells/well in 3 mL of culture media). Then, U-332 and BGD at IC50 concentration each were added and cells were left to grow for 24 h. After incubation, cells were washed 3x in PBS and immediately collected by centrifugation (200×g, 5 min).

The Nuclear Extraction Kit was used in the preparation of nuclear extracts which were then analyzed using NF-κB (p50, p52, p65, c-Rel, RelB) Transcription Factor Assay Kit containing a 96-well plate with immobilized oligonucleotides for NF-κB subunit binding site (5-GGGACTTTCC-3 ́). Active NF-κB heterodimers present in the whole-cell extracts appropriately bind to this oligonucleotide.

For detection of p50, p52, p65, c-Rel or RelB, the primary antibodies recognizing an epitope on these NF-κB subunits were used. The secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) provided sensitive colorimetric readout at OD 450 nm. The data were visualized using Flexstation 3.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and all graphs were prepared using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc multiple comparison Student-Newman-Keuls test (for comparisons of three or more groups) or Student’s t-test (for comparisons of two groups).*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 were considered significant.

Results

MTT-cell viability test

Cytotoxic activity of U-332 and BGD was examined using the MTT test. HL-60 and HL-60/5FU cells were exposed to a broad range of compound concentrations for 24 h (Fig. 3). BGD showed only a week cytotoxic effect (IC50 = 51 μM and 98 μM in HL-60 and HL60/5FU, respectively), while U-332 was 66- and 110-fold more cytotoxic (IC50 = 1.2 μM and 0.9 μM in HL-60 and HL60/5FU, respectively).

Expression level of NF-κB subunit genes

Analysis of the expression level of c-Rel, RelA, RelB, NF-κB1 (p100/p50) and NF-κB2 (p100/p52) genes in the HL-60 and resistant HL-60/5FU cells was performed by real-time PCR. In the HL-60/5FU cells, relative RelA, RelB, NF-κB1, NF-κB2 and c-Rel mRNA expression levels were 1.1–4.4-fold higher than in the parental HL-60 cells (Table 2).

Then, both types of cells were treated for 24 h with U-332 or BGD (at IC50 concentration each). In HL-60 cells, U-332 down-regulated the expression level of c-Rel, RelA, NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 genes, but the most pronounced effect (3.7-fold) was observed for NF-κB2 (Fig. 4a). A potent NF-κB inhibitor, BGD did not influence NF-κB gene expression in this cell line (Fig. 4b).

In the resistant HL-60/5FU cells, U-332 significantly decreased the mRNA level of c-Rel, RelA and NF-κB1 (1.7-, 2- and 4.6-fold, respectively), as compared with control (Fig. 5a). BGD down-regulated the expression of c-Rel, RelB and NF-κB1 while did not influence RelA and NF-κB2 in these cells (Fig. 5b).

Activity of NF-κB subunits

To determine the activity of NF-κB family members in HL-60 and HL60/5FU cell lines, the ELISA-based method was used. Cancer cell lysates were prepared after 24 h exposure of cells to analog U-332 or BGD (at IC50 concentration each).

Consistent with the enhanced gene expression, the activity of cRel, RelA and NF-κB1 subunits was significantly up-regulated in HL-60/5FU cells in comparison with the effect observed in HL-60 cells (Fig. 6a). Incubation of HL-60 cells with U-332 drastically reduced the activity of c-Rel, while BGD did not influence any of NF-κB subunits (Fig. 6b). In the resistant cell line, U-332 potently reduced activity of c-Rel, RelA and NF-κB1, while BGD exerted the strongest effect on c-Rel, RelB and NF-κB1 subunits (Fig. 6c).

The activity of c-Rel, RelA, RelB, NF-κB1 (p100/p50), and NF-κB2 (p100/p52) in untreated HL-60 and HL-60/5FU (a); in HL-60 treated with U-332 or BGD (b); in HL-60/5FU treated with U-332 or BGD (c). Human ABC ELISA kits and extracts from cancer cells treated with U-332 or BGD (at IC50 concentration each) were used. As a positive control Raji nuclear extract was added. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using test t and one-way ANOVA and a post-hoc multiple comparison Student–Newman–Keuls test. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 in comparison with control

Discussion

Chemotherapeutic drugs are meant to kill disseminated cancer cells and prevent metastasis but many cancers develop resistance during treatment [36]. Activation of NF-κB or/and overexpression of ABC transmembrane proteins play a major role in the resistance of tumor cells to chemotherapy [2,3,4]. Many chemotherapeutic agents, including 5-FU, doxorubicin, etoposide or cisplatin have been reported to activate NF-κB and to up-regulate expression of ABC transporters [37,38,39,40]. In several cancer cell lines the inhibition of either NF-κB or ABC transporter activity increased intracellular accumulation of chemotherapeutic drugs [41,42,43]. For example imatinib, a known NF-κB inhibitor, reversed the acquired resistance to doxorubicin by down-regulating the level of ABCB1 through the inhibition of RelA (p65) activity [44]. Therefore, the combination of anticancer drugs with NF-κB and ABC transporter inhibitors can be considered an efficient approach to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy.

Various members of the NF-κB family are constitutively activated in many cancers via one of the two pathways: the canonical pathway involving RelA, NF-κB1 p50 and c-Rel and the non-canonical pathway engaging RelB and NF-κB2 p52. Generally, the canonical NF-κB pathway is known to mediate mostly inflammatory responses, while the non-canonical NF-κB and its components have been shown to have pro-tumorigenic effects in many cancer types. However, there is significant cross-regulation between the components of these pathways, emphasizing the importance of the NF-κB as a single, highly complex system with disease relevance in many types of cancer [45, 46].

In this report, we have shown that in HL-60/5FU resistant cells all 5 NF-κB subunit genes (RelA, RelB, NF-kB1, NF-kB2 and cRel) were significantly up-regulated. By monitoring activation of both, the non-canonical and the canonical NF-κB pathway members we have demonstrated that in HL-60/5FU resistant cells U-332 was involved in the down-regulation of the canonical pathway (RelA, c-Rel and NF-κB1), while BGD inactivated some subunits of both pathways (c-Rel, RelB and NF-κB2). BGD is usually considered a universal inhibitor of both NF-κB pathways. Here, we have shown that in leukemic HL-60/5FU cells the levels of only three out of 5 NF-κB subunits were affected by BGD.

Conclusions

The important finding of the research presented here and in our previous papers [31, 33] was the identification of the novel uracil analog as a potent inhibitor of NF-κB and ABCC1 transporter expression. The inactivation of NF-κB subunits was shown to correlate with the inhibition of ABC transporter activity which may lead to the increased accumulation of a drug in cancer cells.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- 5-FU:

-

5-Fluorouracil

- ABC transporters:

-

ATP-binding cassette transporters

- ABCB1:

-

P-glycoprotein

- ABCC1:

-

Multidrug resistance associate protein 1

- ABCG2:

-

Breast cancer resistance protein

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- BGD:

-

Bengamide

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- ECACC:

-

European collection of cell cultures

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- HRP:

-

Horseradish peroxidase

- MDR:

-

Multidrug resistance

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- TNFRs:

-

Tumor necrosis factor receptors

References

Grove CS, Vassiliou GS. Acute myeloid leukaemia: a paradigm for the clonal evolution of cancer? Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:941–51.

Sonneveld P, Suciu S, Weijermans P, Beksaç M, Neuwirtova R, Solbu G, Segeren CM. Cyclosporin a combined with vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone (VAD) compared with VAD alone in patients with advanced refractory multiple myeloma: an EORTC–HOVON randomized phase III study (06914). Br J Haematol. 2001;115:895–902.

Liu FS. Mechanisms of chemotherapeutic drug resistance in cancer therapy—a quick review, Taiwan. J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48:239–44.

Mansoori B, Mohammadi A, Davudian S, Shirjang S, Baradaran B. The different mechanisms of cancer drug resistance: a brief review. Adv Pharm Bull. 2017;7:339–48.

Noordhuis P, Holwerda U, Van der Wilt CL, Van Groeningen CJ, Smid K, Meijer S, Peters GJ. 5-fluorouracil incorporation into RNA and DNA in relation to thymidylate synthase inhibition of human colorectal cancers. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1025–32.

de la Cueva A, de Molina AR, Álvarez-Ayerza N, Ramos MA, Cebrián A, del Pulgar TG, Lacal JC. Combined 5-FU and ChoKα inhibitors as a new alternative therapy of colorectal cancer: evidence in human tumor-derived cell lines and mouse xenografts. PloS One. 2013;8:e64961.

Focaccetti C, Bruno A, Magnani E, Bartolini D, Principi E, Dallaglio K. Albini a; effects of 5-fluorouracil on morphology, cell cycle, proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy and ROS production in endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115686.

Gao K, Liang Q, Zhao ZH, Li YF, Wang SF. Synergistic anticancer properties of docosahexaenoic acid and 5-fluorouracil through interference with energy metabolism and cell cycle arrest in human gastric cancer cell line AGS cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2971.

Duschinsky R, Pleven E, Heidelberger C. The synthesis of 5-fluoropyrimidines. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:4559–60.

Gardane A, Poonawala M, Vaidya A. Curcumin sensitizes quiescent leukemic cells to anti-mitotic drug 5-fluorouracil by inducing proliferative responses in them. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2016;2:245–52.

Tian ZY, Du GJ, Xie SQ, Zhao J, Gao WY, Wang CJ. Synthesis and bioevaluation of 5-fluorouracil derivatives. Molecules. 2007;12:2450–7.

Carrillo E, Navarro SA, Ramírez A, García MÁ, Griñán-Lisón C, Perán M, Marchal JA. 5-fluorouracil derivatives: a patent review (2012–2014). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2015;25:1131–44.

Dlugosz A, Janecka A. ABC transporters in the development of multidrug resistance in cancer therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22:4705–16.

Gottesman MM, Ambudkar SV. Overview: ABC transporters and human disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2001;33:453–8.

Dean M, Annilo T. Evolution of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily in vertebrates. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2005;6:123–42.

Hooijberg JH, Broxterman HJ, Kool M, Assaraf YG, Peters GJ, Noordhuis P, Jansen G. Antifolate resistance mediated by the multidrug resistance proteins MRP1 and MRP2. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2532–5.

van der Kolk DM, de Vries EG, van Putten WL, Verdonck LF, Ossenkoppele GJ, Verhoef GE, Vellenga E. P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein activities in relation to treatment outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3205–14.

Dean M. ABC transporters, drug resistance, and cancer stem cells. J Mammary Gland Biol. 2009;14:3–9.

Paszel-Jaworska A, Rubiś B, Bednarczyk-Cwynar B, Zaprutko L, Rybczyńska M. Proapoptotic activity and ABCC1-related multidrug resistance reduction ability of semisynthetic oleanolic acid derivatives DIOXOL and HIMOXOL in human acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;242:1–12.

Katayama K, Noguchi K, Sugimoto Y. Regulations of P-glycoprotein/ABCB1/MDR1 in human cancer cells. New J Sci. 2014;2014:1–10.

Zhou G, Kuo MT. NF-κB-mediated induction of mdr1b expression by insulin in rat hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15174–83.

Zhou G, Kuo MT. Wild-type p53-mediated induction of rat mdr1b expression by the anticancer drug daunorubicin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15387–94.

Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF-κB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000034.

Schmitz ML, Baeuerle PA. The p65 subunit is responsible for the strong transcription activating potential of NF-kappa B. EMBO J. 1991;10:3805–17.

Huang B, Yang XD, Lamb A, Chen LF. Posttranslational modifications of NF-κB: another layer of regulation for NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1282–90.

Visekruna A, Volkov A, Steinhoff U. A key role for NF-κB transcription factor c-Rel in T-lymphocyte-differentiation and effector functions. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:1–9.

Coope HJ, Atkinson PGP, Huhse B, Belich M, Janzen J, Holman MJ, Ley SC. CD40 regulates the processing of NF-κB2 p100 to p52. EMBO Rep. 2002;21:5375–85.

Fahy BN, Schlieman MG, Virudachalam S, Bold RJ. Inhibition of AKT abrogates chemotherapy-induced NF-κB survival mechanisms: implications for therapy in pancreatic cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:591–9.

Sakamoto K, Maeda S, Hikiba Y, Nakagawa H, Hayakawa Y, Shibata W, Omata M. Constitutive NF-κB activation in colorectal carcinoma plays a key role in angiogenesis, promoting tumor growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2248–58.

Długosz-Pokorska A, Drogosz J, Pięta M, Janecki T, Krajewska U, Mirowski M, Janecka A. New uracil analogs with exocyclic methylidene group as potential anticancer agents. Anti Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2019. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871520619666191211104128.

Długosz-Pokorska A, Pięta M, Janecki T, Janecka A. New uracil analogs as downregulators of ABC transporters in 5-fluorouracil-resistant human leukemia HL-60 cell line. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46:5831–9.

White KN, Tenney K, Crews P. The Bengamides: a mini-review of natural sources, analogues, biological properties, biosynthetic origins, and future prospects. J Nat Prod. 2017;80:740–55.

Pięta M, Kędzia J, Kowalczyk D, Wojciechowski J, Wolf WM, Janecki T. Enantioselective synthesis of 5-methylidenedihydrouracils as potential anticancer agents. Tetrahedron. 2019;75:2495–505.

Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63.

Winer J, Jung CKS, Shackel I, Williams PM. Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytesin vitro. Anal Biochem. 1999;270:41–9.

Higgins CF. Multiple molecular mechanisms for multidrug resistance transporters. Nature. 2007;446:749–57.

Davoudi Z, Akbarzadeh A, Rahmatiyamchi M, Movassaghpour AA, Alipour M, Nejati-Koshki K, Zarghami N. Molecular target therapy of AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways and multidrug resistance by specific cell penetrating inhibitor peptides in HL-60 cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:4353–8.

Salvia AM, Cuviello F, Coluzzi S, Nuccorini R, Attolico I, Pascale SP, Ostuni A. Expression of some ATP-binding cassette transporters in acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Rep. 2017;9:137–41.

Weldon CB, Burow ME, Rolfe KW, Clayton JL, Jaffe BM, Beckman BS. NF-κB–mediated chemoresistance in breast cancer cells. Surgery. 2001;130:143–50.

Sakuma Y, Yamazaki Y, Nakamura Y, Yoshihara M, Matsukuma S, Koizume S, Miyagi Y. NF-κB signaling is activated and confers resistance to apoptosis in three-dimensionally cultured EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423:667–71.

Zhang J, Lu M, Zhou F, Sun H, Hao G, Wu X, Wang G. Key role of nuclear factor-κB in the cellular pharmacokinetics of adriamycin in MCF-7/Adr cells: the potential mechanism for synergy with 20 (S)-ginsenoside Rh2. Drug Metab Disp. 2012;40:1900–8.

Xing Y, Wang ZH, Ma DH, Han Y. FTY720 enhances chemosensitivity of colon cancer cells to doxorubicin and etoposide via the modulation of P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein 1. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:246–59.

Huang C, Xu D, Xia Q, Wang P, Rong C, Su Y. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance of human hepatic cancer cells by Astragaloside II. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64:1741–50.

Sims JT, Ganguly SS, Bennett H, Friend JW, Tepe J, Plattner R. Imatinib reverses doxorubicin resistance by affecting activation of STAT3-dependent NF-κB and HSP27/p38/AKT pathways and by inhibiting ABCB1. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55509.

Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109:81–96.

Kendellen MF, Bradford JW, Lawrence CL, Clark KS, Baldwin AS. Canonical and non-canonical NF-κB signaling promotes breast cancer tumor-initiating cells. Oncogene. 2014;33(10):1297–305.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by the grant Preludium No DEC-2017/25/N/NZ3/01039 from the National Science Center (NCN) to A.D-P. The funding source had no role in the design of this study and did not play any role during execution, analyses, interpretation of the data or decision to submit results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D-P., T.J. and A.J.; Investigation, A.D-P., M.P. and J.K.; Methodology, A.D-P., M.P. and J. K.; Supervision, T.J. and A.J.; Writing original draft, A.D-P.; Reviewing and editing final version, T.J. and A.J. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Długosz-Pokorska, A., Pięta, M., Kędzia, J. et al. New uracil analog U-332 is an inhibitor of NF-κB in 5-fluorouracil-resistant human leukemia HL-60 cell line. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 21, 18 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-020-0397-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-020-0397-4