Abstract

Background

Long-term sedative use is prevalent and associated with significant morbidity, including adverse events such as falls, cognitive impairment, and sedation. The development of dependence can pose significant challenges when discontinuation is attempted as withdrawal symptoms often develop. We conducted a scoping review to map and characterize the literature and determine opportunities for future research regarding deprescribing strategies for long-term benzodiazepine and Z-drug (zopiclone, zolpidem, and zaleplon) use in community-dwelling adults.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, TRIP, and JBI Ovid databases and conducted a grey literature search. Articles discussing methods for deprescribing benzodiazepines or Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults were selected.

Results

Following removal of duplicates, 2797 articles were reviewed for eligibility. Of these, 367 were retrieved for full-text assessment and 139 were subsequently included for review. Seventy-four (53 %) articles were original research, predominantly randomized controlled trials (n = 52 [37 %]), whereas 58 (42 %) were narrative reviews and seven (5 %) were guidelines. Amongst original studies, pharmacologic strategies were the most commonly studied intervention (n = 42 [57 %]). Additional deprescribing strategies included psychological therapies (n = 10 [14 %]), mixed interventions (n = 12 [16 %]), and others (n = 10 [14 %]). Behaviour change interventions were commonly combined and included enablement (n = 56 [76 %]), education (n = 36 [47 %]), and training (n = 29 [39 %]). Gradual dose reduction was frequently a component of studies, reviews, and guidelines, but methods varied widely.

Conclusions

Approaches proposed for deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs are numerous and heterogeneous. Current research in this area using methods such as randomized trials and meta-analyses may too narrowly encompass potential strategies available to target this phenomenon. Realist synthesis methods would be well suited to understand the mechanisms by which deprescribing interventions work and why they fail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Benzodiazepines and similar sedative hypnotics, including zopiclone, zaleplon, and zolpidem (“Z-drugs”), are extensively prescribed medications in the community setting [1–7]. The annual incidence of long-term benzodiazepine use across North America and Europe is estimated to be between 0.4 % to 6 %, with higher rates of chronic use in patients older than 65 years [5, 8–10]. The prevalence of benzodiazepine use in adults aged 18 to 64 years has remained relatively stable over the past decade, suggesting potential issues with long-term use beyond what is normally indicated [3, 5, 11]. Recent data from Canada suggest important changes in prescribing practices. New prescriptions for benzodiazepines are declining, especially in older adults, while Z-drug use has steadily increased [5]. These trends mirror similar findings from other international studies [8, 12–18].

While indicated only for short-term management of anxiety and insomnia, reasons for acute benzodiazepine and Z-drug therapy transforming into chronic use are complex. Several prescriber related factors are believed to influence this process. These factors may include the prescriber’s attitudes toward these medications and toward the ‘deserving’ patient, deficits in specialized knowledge about sedative prescribing, the clinical work environment, conflicting patient health priorities, and the prescribing practices of others involved in the patient’s care [19, 20]. The perceived or real inaccessibility to alternative treatment modalities may further encourage the renewal of benzodiazepine and Z-drug prescriptions in favor of initiating other interventions that are perceived as less effective [21]. Patient factors including disagreement with appropriateness of cessation, fears of symptom return, withdrawal experiences, and the impression of unsuitability of alternatives also act to promote continued use [22, 23]. Considering the highly varied contributing factors that lead to long-term benzodiazepine and Z-drug use, deprescribing strategies need to be flexible and acceptable to both patients and clinicians.

Deprescribing is the collaborative and supportive process of identifying, modifying, and discontinuing therapies that are no longer indicated or may be causing harm to patients [24, 25]. Research and clinical programs for deprescribing typically focus on elderly patients due to high rates of medication-related morbidity and mortality, such as falls, fractures, motor vehicle collisions, daytime sedation, and cognitive impairment [26–31]. However, stable prevalence of benzodiazepine use and increasing Z-drug use in adults will also require that best-practice deprescribing strategies in this population be identified.

Numerous pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic deprescribing strategies have been reported in the literature with significant heterogeneity in the range and scope of psychological therapies, pharmacotherapy substitution approaches, and gradual dose reduction (GDR) schedules. We conducted a scoping review to map and characterize the literature, identify potential research gaps, and determine opportunities for future systematic syntheses regarding strategies and behaviour change interventions for deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults who are long-term users (i.e., eight weeks or longer).

Methods

Scoping review methods are appropriate for our topic area given the complexity and heterogeneity of existing research [32]. The intention is to characterize and map the literature, identify research gaps, and prioritize targeted areas for future reviews and research [33]. We also aimed to explicate various interventions used in the literature and characterize them according to the Behaviour Change Wheel based on the work of Michie et al. [34]. We followed scoping review procedures slightly modified, but as outlined by Arskey and O’Malley [35] and further explicated by Levac et al. [32] and others [33, 36–39]. Our review was conducted in six iterative stages including developing the research question, identifying relevant articles, selecting articles, extracting data, collating results, and engaging stakeholders through consultation (e.g., presentations on the topic) (Additional file 1).

Definitions and search strategies

As a research team we met and reached consensus on population, intervention, comparator, and outcome definitions (Additional file 1). We limited our target population to patients taking benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in the community or outpatient settings as individuals receiving care in inpatient, long-term care, or residential aged care facilities can differ systematically with respect to numerous factors. These factors include, but are not limited to, the context of the environment, frailty, nature and number of illnesses, and treatment goals. Long-term use was defined as regular use beyond an eight-week period. The target medications for this review included all benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, defined as “zopiclone”, “eszopiclone”, “zolpidem”, or “zaleplon”.

Due to the broad nature of scoping reviews, we did not limit our research question to a particular type of intervention or comparator and included studies investigating pharmacologic, psychological, and various mixed methods of discontinuing benzodiazepine or Z-drug therapy. We classified pharmacologic interventions as those adding additional drug therapy (non-benzodiazepine or Z-drug) to facilitate discontinuation of the sedative or mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Psychological interventions were those utilizing behavioural techniques, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), to reduce benzodiazepine or Z-drug use. We categorized studies as mixed interventions if they compared various pharmacologic, psychological, or other interventions with each other. GDR included employing a taper regimen or switching between sedatives to facilitate benzodiazepine or Z-drug withdrawal. The remaining intervention types not falling within these categories were classified as ‘other’ (i.e., letter or brief consultation).

We collaborated with a medical science librarian to develop search methods for each database and to identify key terms and relevant medical subject headings. Our searches were developed to model the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) format for clinical questions [40].We searched PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, and JBI Ovid databases from inception to December 19, 2013. Systematic combinations of the medical subject headings “benzodiazepine”, “hypnotics and sedatives”, “substance withdrawal syndrome”, “dependency”, “sleep disorders”, and “anxiety disorders” were used together with the keywords “hypnotic”, “sedative”, “zopiclone”, “eszopiclone”, “zolpidem”, “zaleplon”, “withdraw*”, “deprescrib*”, “taper”, “stop”, and “discontinu*”. Search terms were translated as appropriate for each database.

To identify further references not captured in the published medical literature, we used relevant sections of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health’s (CADTH) “Grey Matters: a practical search tool for evidence-based medicine” [41] to search 69 international grey literature sources from the earliest available date through January 30, 2014. We also searched Opengrey (SIGLE), Google Advanced, screening the first 100 results for relevance to our clinical question, and the Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database for clinical practice guidelines concerning deprescribing of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Additional articles potentially relevant to our objectives were identified through reviewing reference lists of articles captured in our initial searches and by engaging with experts and colleagues.

Study selection

We used pre-defined inclusion criteria to select articles identified through the search strategy that were relevant to our study objectives. We included those studies that were published in English and investigated or discussed methods for discontinuing benzodiazepines and sedative hypnotics in community-dwelling individuals aged 18 years and older. Based on our pre-determined criteria, we did not include studies that exclusively investigated benzodiazepine and Z-drug use in patients with conditions other than anxiety or insomnia disorders. We excluded studies in animals, pediatric patients (<18 years old), and short-term users of benzodiazepines or Z-drugs (less than eight weeks). We did not include studies investigating non-clinical outcomes (e.g., electroencephalography and brain imaging studies), and articles not investigating benzodiazepine and Z-drug discontinuation as a primary focus. With the exception of case-reports, case-series, and commentaries, articles were not excluded based on methodology or publication type as we sought to identify trends across the wide spectrum of research and publications in the area [35]. Original investigations, research syntheses, guidelines, and narrative review articles were all eligible for inclusion in order to capture potential differences amongst these publications with respect to benzodiazepine and Z-drug deprescribing recommendations. Indicators of study quality were broadly assessed as a means to understand the nature of research methods used and reported, but study quality was not used as an inclusion criterion.

The list of article titles and abstracts resulting from the database and grey literature searches were scanned independently by two reviewers (AP and JB), who assigned a value of “include”, “exclude”, or “assess further” to each reference. After the initial screening phase, full-text articles were retrieved and independently assessed by AP and JB for inclusion in the review using forms for determining eligibility criteria. Disagreements between the two assessors were discussed, and a third author (AM) was consulted if agreement could not be reached.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

The data abstraction tool was drafted and revised through meetings throughout the stages of the review (Additional file 1). The standardized form was designed to capture information about the year of publication, country of origin, study type, target medication investigated, types of interventions, GDR protocol if used, duration of intervention, and information about the participants. Behaviour change interventions used in original research trials were categorized according to the Behaviour Change Wheel as enablement (“increasing means/reducing barriers to increase capability or opportunity”), training (“imparting skills”), persuasion (“using communication to induce positive or negative feelings or stimulate action”), environmental restructuring (“changing the physical or social context”), modeling (“providing an example for people to aspire to”), education (“increasing knowledge or understanding”), incentivisation (“creating expectation of reward”), coercion (“creating expectation of punishment or cost”), and restriction (“using rules to reduce opportunity to engage in target behaviour”) [34]. Study methodology was characterized according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) “Assessing Risk of Bias and Confounding in Observational Studies of Interventions or Exposures: Further Development of the RTI Item Bank” [42] with the addition of systematic reviews and narrative review articles. We categorized general data regarding the direction of effect of endpoints related to benzodiazepine and Z-drug discontinuation as a formal evaluation of the effect size of specific interventions is beyond the objective of a scoping review.

Prior to beginning the abstractions, an abstraction meeting was held to outline the process and model how to characterize intervention functions to establish consistency among team members. Initial articles were abstracted in a group environment so that discussion could occur surrounding issues or uncertainties regarding intervention function categorization. Following the initial abstractions one investigator (AP) reviewed all article abstractions for consistency in terminology, accuracy, and comprehensiveness. The PRISMA checklist form is provided as Additional file 2.

Results

Search

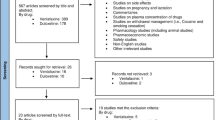

Our literature search yielded 2797 articles after duplicates were removed. Review of titles and abstracts led to retrieval of 367 full-text articles for assessment (Fig. 1). Of these, 74 original research studies and 65 review articles or guidelines were included (Additional file 3) [8, 43–180]. The absence of benzodiazepine or Z-drug discontinuation strategies as a major focus of the intervention or outcome was the most frequent reason for excluding articles.

Description of articles

Deprescribing articles for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs were published between 1982 and 2014 with no apparent trend towards growing publications in this field over the past 30 years (Table 1). Research was primarily conducted in the United States (27 %) and United Kingdom (24 %). Articles were published in a variety of journals with scopes including psychiatry (n = 43 [31 %]), general/primary care (n = 37 [27 %]), pharmacology (n = 28 [20 %]), psychology and behavioural sciences (n = 11 [8 %]), and addiction (n = 11 [8 %]). Most original research studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 52 [37 %]), but nearly 50 % of all included articles were non-original research (Table 1). The majority of studies were relatively small, with less than 100 participants in total (n = 51 [69 %]). The setting of original research included primary care and outpatient clinics (n = 45 [61 %]), specialty clinics (n = 14 [19 %]), and university research units (n = 8 [11 %]), while seven studies did not report setting details (10 %).

Amongst research trials, most (n = 36 [49 %]) investigated patient populations taking benzodiazepines for multiple reasons. Insomnia or anxiety disorders were the primary diagnosis in 16 studies each (22 %). Fewer (n = 6 [8 %]) trials focused on patients with panic disorder. In contrast, 57 % (n = 37) of review articles examined mixed conditions, 11 % (n = 7) insomnia, 17 % (n = 11) anxiety disorders, and 15 % (n = 10) panic disorders. The distribution of studies reporting a mean age of 40 to 49 years, 50 to 59 years and 60 to 69 years, was 43 % (n = 32), 18 % (n = 13), and 19 % (n = 14), respectively. The duration of prior benzodiazepine or Z-drug use varied widely among studies and details concerning the length of therapy were not reported in 41 % (n = 30). The mean duration of benzodiazepine or Z-drug use was typically less than a decade (n = 30 [41 %]). The majority of original trials (n = 41 [55 %]) investigated the discontinuation of any benzodiazepine, whereas 16 % (n = 12) examined both benzodiazepine and Z-drug discontinuation. Only three (4 %) of 74 original studies exclusively examined strategies for stopping Z-drugs. The remaining studies enrolled patients only if they were taking specific benzodiazepines, most frequently alprazolam (n = 11), diazepam (n = 7), and lorazepam (n = 6).

The general direction of effect for the endpoint of discontinuation of benzodiazepine or Z-drug therapy was noted for each research trial, regardless of the type of intervention studied. Of original research studies, 41 % (n = 30) of studies demonstrated a negative (or non-significant) effect of the intervention being investigated. A positive effect was demonstrated in 47 % (n = 35) of studies, while 12 % (n = 9) of research studies did not provide sufficient data to clearly assess the direction of the effect (Additional file 3).

Deprescribing strategies

Pharmacologic

Among original research studies, pharmacologic interventions were the most common types of interventions assessed for their impact on reducing benzodiazepine and Z-drug exposure (n = 42 [57 %]) (Table 2). Thirty-three studies investigated the addition of pharmacologic therapies to facilitate benzodiazepine or Z-drug discontinuation. Amongst these, buspirone was the most frequently studied therapy in RCTs (n = 4) and nonrandomized controlled trials (n = 3), with a total of 275 subjects. Melatonin was studied in five trials, of which four were RCTs with 244 subjects. Sixteen other additive pharmacologic agents were studied, which included beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists (n = 3), anti-seizure drugs such as carbamazepine, pregabalin, and valproate (n = 5), and antidepressants such as imipramine, paroxetine, and trazodone (n = 5). Other medications investigated were ondansetron (n = 1) and progesterone (n = 1).

Gradual dose reduction

Original research investigations of pharmacologic, psychological, mixed, and other interventions frequently included GDR as a component of the discontinuation method (60 of 74 [80 %]). However, the types of GDR regimens employed varied dramatically among trials and 15 studies did not report details about their GDR methods. Stabilization (i.e., establishing a consistent daily dose) of benzodiazepine or Z-drug dose prior to the initiation of tapering was a strategy employed in 28 % of studies. As part of the GDR regimen, 31 (42 %) trials established flexible taper plans, which involved altering the rate of taper based on patient symptoms. The remaining trials established a uniform tapering regimen that was applied to all subjects. In 13 trials (18 %), participants were switched to another agent, most frequently diazepam (n = 10), but also Z-drugs including zopiclone (n = 2) and zolpidem (n = 1). The time frame over which GDR was conducted ranged from one to more than 16 weeks with the most common (n = 11) being four weeks (median 6 weeks, interquartile range 4–8 weeks). Twenty studies employing GDR did not report the time frame of their taper regimen. The most common taper rate among studies (n = 16) was decreasing the original dose by 25 % weekly (i.e., 75 % of original dose for one week, then 50 % of original dose for one week, then 25 % of original dose for one week, then stop). Seven studies outlined a slower approach, decreasing the dose by 25 % every two to four weeks. Shorter tapers were also reported in seven studies, with the dose reduced by half for one to two weeks before the benzodiazepine or Z-drug was discontinued.

The majority of review articles and clinical practice guidelines (60 of 65 [92 %]) recommended GDR as part of a discontinuation strategy (Table 2). Recommendations concerning GDR strategy varied widely but a flexible approach and substitution of a long-acting benzodiazepine were frequent suggestions.

Psychological therapies

Psychological therapies to facilitate discontinuation of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs were studied in 10 trials (14 %), with 60 % of these trials utilizing CBT (Table 2). Other strategies employed via both group and individualized therapies included anxiety management, stress management, and psychotherapy. Nine of these 10 trials were RCTs with a total of 408 patients.

Mixed and other interventions

Mixed interventions comparing various pharmacologic, psychological, or other interventions were the focus of 12 (16 %) studies (Table 2). Five of these 12 trials compared more than two types of interventions. Common interventions included psychological therapy (most frequently CBT), GDR alone, and usual care. Other interventions that were investigated in 14 % of original research studies included interventions such as sending a letter or detailed information to patients and brief counseling by clinicians.

Intervention functions

Six of the nine intervention types described by Michie et al., [34] were used in the research studies included. The majority of original studies included a single intervention function (n = 39 [53 %]), while the remainder combined two (n = 12 [16 %]), three (n = 21 [28 %]), or four (n = 2 [3 %]) distinct functions (Additional file 3). The most common method employed was enablement, which was used in 76 % (n = 56) of studies. The majority of studies using enablement techniques attempted to achieve benzodiazepine or Z-drug cessation by testing the effect of GDR, additional pharmacotherapy, or psychological therapies. Education and training were also frequent elements assessed by research studies, being a component of 47 % (n = 35) and 38 % (n = 28) of studies, respectively. A total of 11 studies investigated persuasion interventions (15 %), which frequently involved the physician sending a letter to patients to explain the harms of benzodiazepines or Z-drugs and encouraging discontinuation. Three trials tested environmental restructuring techniques to facilitate discontinuation. In addition to other strategies, one trial evaluated modeling as a component of a patient information package [8].

Discussion

We identified 139 articles for deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults that included a range of different strategies and behaviour change interventions. This is in contrast to recent meta-analyses that included 32 studies or fewer [117, 136, 138]. While meta-analyses of data can offer valuable answers to specific research and clinical questions, the strict inclusion criteria based on study methodology and quality can limit the amount of information they provide on the research area as a whole. Research and publications that would be characterized as lower levels of evidence in hierarchies [181–183] (e.g., non-randomized trials, guidelines, narrative reviews) can be captured in scoping reviews, which is important in many clinical questions given the kinds of evidence that inform clinicians and patients in decision-making [184]. In our scoping review, we included systematic reviews, individual RCTs, practice guidelines, reviews, and other study designs to characterize the literature, identify research gaps and future research priorities, and determine opportunities for future systematic syntheses regarding deprescribing strategies. This more inclusive approach reflects the sources of information utilized by clinicians, especially for therapeutic decisions that require individualized and flexible care plans, such as benzodiazepine and Z-drug discontinuation [185].

Pharmacologic interventions have been the primary discontinuation strategy reported on in the majority of studies within previous meta-analyses [117, 136, 138]. Likewise, our scoping review found that the addition of pharmacologic agents to facilitate discontinuation has been the most commonly studied type of intervention in RCTs (31 trials, totaling 2273 patients). This method of discontinuation may be counterintuitive to both prescribers and patients as risks for different adverse events and increased costs are inherent within this approach. Despite the majority of trials studying this method, non-original review articles and guidelines included in our scoping review did not discuss this approach as frequently. This is especially important to consider given the large degree of variability and tensions that can exist with the use of different forms of evidence in clinical decision-making [186–188]. Depending on the practitioner, guidelines and narrative reviews may be significantly influential in decision-making. Patients will also inherently use various forms of information about medications in their decision-making, much of which will not necessarily include information from clinical trials but that is readily accessible on the internet [189].

Our review revealed that benzodiazepine and Z-drug deprescribing interventions are numerous, largely heterogeneous, and poorly described. The pace of publication annually remained stable, indicating maintained interest in this field. Estimates of effect size direction, while not attributable to a specific intervention or intervention type, were mixed with 47 % of trials being positive, 41 % negative, and 12 % undetermined, suggesting a lack of clarity regarding how to best deprescribe benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Replication of strategies in the clinical practice setting with fidelity to interventions that were studied is nearly impossible owing to the large number of approaches examined and the lack of details provided in some reports. Guidelines such as the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) [190] and the checklist by the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) [191] should be used to describe interventions in sufficient detail to allow for their replication not only for subsequent research but in clinical practice. It would also allow investigators to better develop implementation strategies for various interventions in a range of settings using implementation frameworks [192].

Limited theoretical underpinnings of interventions combined with the significant heterogeneity and complexity of strategies as found in our review, presents challenges in helping to understand and explain the mechanisms by which interventions work, why they work, for whom, and in which contexts. Furthermore, with rising use of Z-drugs and other psychotropics for insomnia (e.g., quetiapine) [193] we need to understand whether strategies that work for benzodiazepines are in fact those that work for discontinuing other types of hypnotics. We recommend that a realist synthesis [194] approach be used in future syntheses given the complexity of these issues and the need to better understand the mechanisms by which deprescribing interventions for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs work and why they fail [195].

The generalizability of results from available studies is problematic due to the risk of sample distortion bias and selection bias affecting the findings. Across several studies, subjects participated because they were already motivated to stop their benzodiazepine or Z-drug. For many existing users, there is significant reluctance or refusal to discontinue benzodiazepines and Z-drugs when given the opportunity [22, 196, 197]. Additionally, long-term users of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs may have comorbidities that would exclude them from participating in many deprescribing clinical trials. The goals of care in patients with ongoing comorbidities may be quite different and benzodiazepine and Z-drug deprescribing may not be an immediate priority. Participants in trials were often of younger age (i.e., 40 to 50 years), which does not match with the older population targeted by deprescribing initiatives that aim to reduce harm. Research in the area of deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs should focus on older people with a wide range of comorbidities.

To date, the outcome of interest in benzodiazepine and Z-drug deprescribing research has largely been whether or not treatment was successfully stopped. Clinical outcomes such as impact on reducing falls, fractures, quality of life, and mortality have been evaluated less frequently [108, 198]. Future research should determine the specific harms associated with long term sedative use, especially in vulnerable groups (e.g., frail adults, patients with multiple comorbidities), and aim to identify which patients benefit from benzodiazepine and Z-drug discontinuation in terms of quality of life, morbidity, and mortality.

There are limitations to this review. First, our search may not have been exhaustive, despite the search of multiple databases and grey literature sources. The lack of standardized medical subject headings in the developing area of deprescribing may have partially contributed to this. Second, we did not extract specific information about interventions studied and reviewed within the literature to determine which strategies are optimal for facilitating benzodiazepine and Z-drug discontinuation, as this is not the intended purpose of a scoping review. Third, although a predefined abstraction tool and classification scheme can minimize subjectivity among abstractors, there may be variability among investigators.

Conclusions

Long-term and inappropriate use of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs remains a problem in community dwelling adults. Numerous pharmacologic, psychological, and other interventions have been used to support long-term benzodiazepine and Z-drug discontinuation, yet strategies are diverse and often poorly reported in sufficient detail to allow replication in future research or clinical practice. Using scoping review methods for this complex problem allowed for inclusion of a greater breadth of literature and the freedom to characterize and identify existing gaps in research, whereas traditional syntheses methods restrict clinicians to mostly RCT data of pharmacologic augmentation of GDR. Our results indicate that the current research in this area using methods such as RCTs and meta-analysis may too narrowly encompass the potential strategies available to target this phenomenon. Future studies in this area should describe interventions in sufficient detail, including information on various behaviour change techniques, to allow for their replication in research and clinical practice. This process could be facilitated by the use of standardized reporting guidelines and various checklists that currently exist [190, 191]. More research regarding the impact of deprescribing strategies on patient-centered outcomes in real-word settings is required. Realist synthesis methods would be well suited to understand the mechanisms by which deprescribing interventions for benzodiazepines and Z-drugs work and why they fail.

Abbreviations

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioural therapy

- GDR:

-

Gradual dose reduction

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Ohayon MM, Lader MH. Use of psychotropic medication in the general population of France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:817–25.

Olfson M, Pincus HA. Use of benzodiazepines in the community. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1235–40.

Neutel CI. The epidemiology of long-term benzodiazepine use. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17:189–97.

Paulose-Ram R, Safran MA, Jonas BS, Gu Q, Orwig D. Trends in psychotropic medication use among U.S. adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:560–70.

Alessi-Severini S, Boulton JM, Enns MW, Dahl M, Collins DM, Chateau D, et al. Use of benzodiazepines and related drugs in Manitoba: a population-based study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2:e208–16.

Mamdani M, Rapoport M, Shulman KI, Herrmann N, Rochon PA. Mental health-related drug utilization among older adults: prevalence, trends, and costs. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:892–900.

Hogan DB, Maxwell CJ, Fung TS, Ebly EM. Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Prevalence and potential consequences of benzodiazepine use in senior citizens: results from the Canadian study of health and aging. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:72–7.

Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:890–8.

Cunningham CM, Hanley GE, Morgan S. Patterns in the use of benzodiazepines in British Columbia: examining the impact of increasing research and guideline cautions against long-term use. Health Policy. 2010;97:122–9.

Lagnaoui R, Depont F, Fourrier A, Abouelfath A, Begaud B, Verdoux H, et al. Patterns and correlates of benzodiazepine use in the French general population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:523–9.

van Hulten R, Isacson D, Bakker A, Leufkens HG. Comparing patterns of long-term benzodiazepine use between a Dutch and a Swedish community. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12:49–53.

Patten SB, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Kassam A, Sabapathy CD. Pharmacoepidemiology of benzodiazepine and sedative-hypnotic use in a Canadian general population cohort during 12 years of follow-up. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:792–9.

Esposito E, Barbui C, Patten SB. Patterns of benzodiazepine use in a Canadian population sample. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18:248–54.

De Wilde S, Carey IM, Harris T, Richards N, Victor C, Hilton SR, et al. Trends in potentially inappropriate prescribing amongst older UK primary care patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:658–67.

Lai HY, Hwang SJ, Chen YC, Chen TJ, Lin MH, Chen LK. Prevalence of the prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications at ambulatory care visits by elderly patients covered by the Taiwanese national health insurance program. Clin Ther. 2009;31:1859–70.

Smolders M, Laurant M, van Rijswijk E, Mulder J, Braspenning J, Verhaak P, et al. The impact of co-morbidity on GPs’ pharmacological treatment decisions for patients with an anxiety disorder. Fam Pract. 2007;24:538–46.

Ford ES, Wheaton AG, Cunningham TJ, Giles WH, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Trends in outpatient visits for insomnia, sleep apnea, and prescriptions for sleep medications among US adults: findings from the national ambulatory medical care survey 1999–2010. Sleep. 2014;37:1283–93.

Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine Use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:136–42.

Sirdifield C, Anthierens S, Creupelandt H, Chipchase SY, Christiaens T, Siriwardena AN. General practitioners’ experiences and perceptions of benzodiazepine prescribing: systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:191.

Martinsson G, Fagerberg I, Wiklund-Gustin L, Lindholm C. Specialist prescribing of psychotropic drugs to older persons in Sweden—register-based study of 188,024 older persons. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:197.

Everitt H, McDermott L, Leydon G, Yules H, Baldwin D, Little P. GPs’ management strategies for patients with insomnia: a survey and qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e112–9.

Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2013;30:793–807.

Cook JM, Biyanova T, Masci C, Coyne JC. Older patient perspectives on long-term anxiolytic benzodiazepine use and discontinuation: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1094–100.

Frank C. Deprescribing: a new word to guide medication review. CMAJ. 2014;186:407–8.

Woodward MC. Deprescribing: achieving better health outcomes for older people through reducing medications. J Pharm Pract Res. 2003;33:323–8.

Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. CMAJ. 2000;162:225–33.

Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331:1169.

Neutel CI, Perry S, Maxwell C. Medication use and risk of falls. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11:97–104.

Wagner AK, Zhang F, Soumerai SB, Walker AM, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, et al. Benzodiazepine use and hip fractures in the elderly: who is at greatest risk? Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1567–72.

Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, Morris AD, Reid IC, McDevitt DG, et al. Association of road-traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet. 1998;352:1331–6.

McIntosh B, Clark M, Spry C. Benzodiazepines in older adults: a review of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, and guidelines. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK174561/. Accessed 16 Nov 2014.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Lillie E, Perrier L, Horsley T, et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:114.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

Arskey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Valaitis R, Martin-Misener R, Wong ST, MacDonald M, Meagher-Stewart D, Austin P, et al. Methods, strategies and technologies used to conduct a scoping literature review of collaboration between primary care and public health. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2012;13:219–36.

Bragge P, Clavisi O, Turner T, Tavender E, Collie A, Gruen RL. The global evidence mapping initiative: scoping research in broad topic areas. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:92.

Brien SE, Lorenzetti DL, Lewis S, Kennedy J, Ghali WA. Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implement Sci. 2010;5:2.

Rumrill PD, Fitzgerald SM, Merchant WR. Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work. 2010;35:399–404.

Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12–3.

Grey matters: a practical search tool for evidence-based medicine. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2013. http://www.cadth.ca/en/resources/finding-evidence-is/grey-matters. Accessed 19 Jan 2014.

Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, Dryden DM, Hartling L. Assessing risk of bias and confounding in observational studies of interventions or exposures: further development of the RTI item bank. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK154461/. Accessed 15 Mar 2014.

Abelson JL, Curtis GC. Discontinuation of alprazolam after successful treatment of panic disorder: a naturalistic follow-up study. J Anxiety Disord. 1993;7:107–17.

Ahmed M, Westra HA, Stewart SH. A self-help handout for benzodiazepine discontinuation using cognitive behavioral therapy. Cong Behav Pract. 2008;15:317–24.

Allain H, Le Coz F, Borderies P, Schuck S, Giclais DL, Patat A, et al. Use of zolpidem 10 mg as a benzodiazepine substitute in 84 patients with insomnia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1998;13:551–9.

Ashton H. The treatment of benzodiazepine dependence. Addiction. 1994;89:1535–41.

Ashton CH, Rawlins MD, Tyrer SP. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of buspirone in diazepam withdrawal in chronic benzodiazepine users. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:232–8.

Baillargeon L, Landreville P, Verreault R, Beauchemin JP, Grégoire JP, Morin CM. Discontinuation of benzodiazepines among older insomniac adults treated with cognitive-behavioural therapy combined with gradual tapering: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 2003;169:1015–20.

Ballenger JC. Long-term pharmacologic treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52 Suppl 2:18–23.

Ballenger JC, Pecknold J, Rickels K, Sellers EM. Medication discontinuation in panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54 Suppl 10:15–21.

Bartholomew S. Benzodiazepine dependence in the elderly. J Am Acad Phys Assist. 1990;3:535–9.

Bashir K, King M, Ashworth M. Controlled evaluation of brief intervention by general practitioners to reduce chronic use of benzodiazepines. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:408–12.

Belanger L, Belleville G, Morin C. Management of hypnotic discontinuation in chronic insomnia. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4:583–92.

Belleville G, Guay C, Guay B, Morin CM. Hypnotic taper with or without self-help treatment of insomnia: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:325–35.

Blais D, Petit L. Benzodiazepines: dependence and a therapeutic approach to gradual withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 1990;36:1779–82.

Bobes J, Rubio G, Teran A, Cervera G, Lopez-Gomez V, Vilardaga I, et al. Pregabalin for the discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepines use: an assessment of its effectiveness in daily clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:301–7.

Burrows GD. Managing long-term therapy for panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51 Suppl 11:9–12.

Burrows GD, Norman TR, Judd FK, Marriott PF. Short-acting versus long-acting benzodiazepines: discontinuation effects in panic disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24 Suppl 2:65–72.

Cantopher T, Olivieri S, Cleave N, Edwards JG. Chronic benzodiazepine dependence: a comparative study of abrupt withdrawal under propranolol cover versus gradual withdrawal. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:406–11.

Chang F. Strategies for benzodiazepine withdrawal in seniors. Can Pharm J. 2005;138:38–40.

Choy Y. Managing side effects of anxiolytics. Primary Psychiatry. 2007;14:68–76.

Chung KF, Cheung RCH, Tam JWY. Long-term benzodiazepine users - characteristics, views and effectiveness of benzodiazepine reduction information leaflet. Singapore Med J. 1999;40:138–43.

Cormack MA, Sinnott A. Psychological alternatives to long-term benzodiazepine use. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1983;33:279–81.

Cormack MA, Sweeney KG, Hughes-Jones H, Foot GA. Evaluation of an easy, cost-effective strategy for cutting benzodiazepine use in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:5–8.

Crouch G, Robson M, Hallstrom C. Benzodiazepine dependent patients and their psychological treatment. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1988;12:503–10.

Davidson JR. Continuation treatment of panic disorder with high-potency benzodiazepines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51 Suppl 12:31–7.

Dell’osso B, Lader M. Do benzodiazepines still deserve a major role in the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A critical reappraisal. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28:7–20.

Benzodiazepines: good practice guidelines for clinicians. Department of Health and Children, Ireland. 2002. http://hdl.handle.net/10147/46748. Accessed 19 Jan 2014.

Drug misuse and dependence: UK guidelines on clinical management. Department of Health (England), the Scottish Government, Welsh Assembly Government, and Northern Ireland Executive. 2007. http://www.nta.nhs.uk/guidelines.aspx. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Drake J. Temazepam ‘planpak’: a multicentre general practice trial in planned benzodiazepine hypnotic withdrawal. Curr Med Res Opin. 1991;12:390–3.

Dubovsky SL. Generalized anxiety disorder: new concepts and psychopharmacologic therapies. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51 Suppl 1:3–10.

DuPont RL. Thinking about stopping treatment for panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:38–45.

DuPont RL. A practical approach to benzodiazepine discontinuation. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24 Suppl 2:81–90.

El-Guebaly N, Sareen J, Stein MB. Are there guidelines for the responsible prescription of benzodiazepines? Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:709–14.

Elsesser K, Sartory G, Maurer J. The efficacy of complaints management training in facilitating benzodiazepine withdrawal. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:149–56.

Office-based outpatient withdrawal techniques: a guide–anxiolytic/sedative/hypnotic drugs. Federation of Texas Psychiatry. 2002. http://www.txpsych.org/guidelinesanxiolyticsedativehypnotic.htm. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Fraser D, Peterkin GS, Gamsu CV, Baldwin PJ. Benzodiazepine withdrawal: a pilot comparison of three methods. Br J Clin Psychol. 1990;29:231–3.

Fyer AJ, Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, Campeas R, Levin A, Davies SO, et al. Discontinuation of alprazolam treatment in panic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:303–8.

Garfinkel D, Zisapel N, Wainstein J, Laudon M. Facilitation of benzodiazepine discontinuation by melatonin: a new clinical approach. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2456–60.

Gilhooly TC, Webster MG, Poole NW, Ross S. What happens when doctors stop prescribing temazepam? Use of alternative therapies. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48:1601–2.

Clinical comparison of paroxetine and placebo on the symptoms emerging during the taper phase of a chronic benzodiazepine treatment, in patients suffering from a variety of anxiety disorders. GlaxoSmithKline. 2008. http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/study/29060/730#rs. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Gosselin P, Ladouceur R, Morin CM, Dugas MJ, Baillargeon L. Benzodiazepine discontinuation among adults with GAD: a randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:908–19.

Hadley SJ, Mandel FS, Schweizer E. Switching from long-term benzodiazepine therapy to pregabalin in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:461–70.

Hallström C, Crouch G, Robson M, Shine P. The treatment of tranquilizer dependence by propranolol. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64 Suppl 2:40–4.

Harangozo J, Magyar I, Faludy G. Use of benzodiazepines in psychiatry. Ther Hung. 1991;39:103–11.

Hayward P, Wardle J, Higgitt A. Benzodiazepine research: current findings and practical consequences. Br J Clin Psychol. 1989;28:307–27.

Heather N, Bowie A, Ashton H, McAvoy B, Spencer I, Brodie J, et al. Randomised controlled trial of two brief interventions against long-term benzodiazepine use: outcome of intervention. Addict Res Theory. 2004;12:141–54.

Higgitt AC, Lader MH, Fonagy P. Clinical management of benzodiazepine dependence. BMJ. 1985;91:688–90.

Hofmann SG, Spiegel DA. Panic control treatment and its applications. J Psychother Pract Res. 1999;8:3–11.

Holm KJ, Goa KL. Zolpidem: an update of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs. 2000;59:865–89.

Hopkins DR, Sethi KB, Mucklow JC. Benzodiazepine withdrawal in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1982;32:758–62.

Huston PG. Moderating benzodiazepine use in the elderly. Can Fam Phys. 1992;38:2459–67.

Jensen B. Benzodiazepine comparison chart. In: Jensen B, Regier L, editors. RxFiles Drug Comparison Charts. 9th ed. Saskatoon: Saskatoon Health Region; 2013. p. 101.

Keck Jr PE, McElroy SL, Friedman LM. Valproate and carbamazepine in the treatment of panic and posttraumatic stress disorders, withdrawal states, and behavioral dyscontrol syndromes. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12 Suppl 1:36S–41S.

Alcohol and other drug withdrawal practice guidelines. Drug and Alcohol Clinical Advisory Service. 2009. http://www.dacas.org.au/Clinical_Resources/Clinical_Guidelines.aspx. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Klein E. The role of extended-release benzodiazepines in the treatment of anxiety: a risk-benefit evaluation with a focus on extended-release alprazolam. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63 Suppl 14:27–33.

Klein E, Colin V, Stolk J, Lenox RH. Alprazolam withdrawal in patients with panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder: vulnerability and effect of carbamazepine. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1760–6.

Kunz D, Bineau S, Maman K, Milea D, Toumi M. Benzodiazepine discontinuation with prolonged-release melatonin: hints from a German longitudinal prescription database. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:9–16.

Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited–will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106:2086–109.

Lader M. Long-term anxiolytic therapy: the issue of drug withdrawal. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48 Suppl 12:12–6.

Lader M, Farr I, Morton S. A comparison of alpidem and placebo in relieving benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;8:31–6.

Lader M, Olajide D. A comparison of buspirone and placebo in relieving benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7:11–5.

Lader M, Tylee A, Donoghue J. Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:19–34.

Lähteenmäki R, Puustinen J, Vahlberg T, Lyles A, Neuvonen PJ, Partinen M, et al. Melatonin for sedative withdrawal in older patients with primary insomnia: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;77:975–85.

Landry MJ, Smith DE, McDuff DR, Baughman 3rd OL. Benzodiazepine dependence and withdrawal: identification and medical management. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5:167–75.

Lemoine P, Allain H, Janus C, Sutet P. Gradual withdrawal of zopiclone (7.5 mg) and zolpidem (10 mg) in insomniacs treated for at least 3 months. Eur Psychiatry. 1995;10(3):161S–5S.

Lemoine P, Kermadi I, Garcia-Acosta S, Garay RP, Dib M. Double-blind, comparative study of cyamemazine vs. bromazepam in the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:131–7.

Lopez-Peig C, Mundet X, Casabella B, del Val JL, Lacasta D, Diogene E. Analysis of benzodiazepine withdrawal program managed by primary care nurses in Spain. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:684.

MacKinnon GL, Parker WA. Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: a literature review and evaluation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1982;9:19–33.

Insomnia: benzodiazepines, complementary medicines and non-drug treatments. National Prescribing Service. 2002. http://www.nps.org.au/publications/health-professional/nps-news/2006/nps-news-24. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Marriott S, Tyrer P. Benzodiazepine dependence: avoidance and withdrawal. Drug Saf. 1993;9:93–103.

Mercier-Guyon C, Chabannes JP, Saviuc P. The role of captodiamine in the withdrawal from long-term benzodiazepine treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:1347–55.

Michelini S, Cassano GB, Frare F, Perugi G. Long-term use of benzodiazepines: tolerance, dependence and clinical problems in anxiety and mood disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1996;29:127–34.

Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, Radouco-Thomas M, Leblanc J, Vallières A. Randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:332–42.

Morin CM, Colecchi CA, Ling WD, Sood RK. Cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation among hypnotic-dependent patients with insomnia. Behav Ther. 1995;26:733–45.

Morton S, Lader M. Buspirone treatment as an aid to benzodiazepine withdrawal. J Psychopharmacol. 1995;9:331–5.

Mugunthan K, McGuire T, Glasziou P. Minimal interventions to decrease long-term use of benzodiazepines in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61:e573–8.

Murphy SM, Tyrer P. A double-blind comparison of the effects of gradual withdrawal of lorazepam, diazepam and bromazepam in benzodiazepine dependence. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:511–6.

Nakao M, Takeuchi T, Nomura K, Teramoto T, Yano E. Clinical application of paroxetine for tapering benzodiazepine use in non-major-depressive outpatients visiting an internal medicine clinic. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:605–10.

Nardi AE, Freire RC, Valenca AM, Amrein R, de Cerqueira AC, Lopes FL, et al. Tapering clonazepam in patients with panic disorder after at least 3 years of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:290–3.

Nathan RG, Robinson D, Cherek DR, Sebastian CS, Hack M, Davison S. Alternative treatments for withdrawing the long-term benzodiazepine user: a pilot study. Int J Addict. 1986;21:195–211.

Management options for improving sleep. National Prescribing Service. 2010. http://www.nps.org.au/publications/health-professional/prescribing-practice-review/2010/prescribing-practice-review-49. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Benzodiazepines: managing withdrawal. National Prescribing Service. 1999. http://www.nps.org.au/publications/health-professional/nps-news/2006/nps-news-4. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Benzodiazepine and z-drug withdrawal. National Health Service. 2013. http://cks.nice.org.uk/benzodiazepine-and-z-drug-withdrawal. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

What’s wrong with prescribing hypnotics? Drug Ther Bull.http://dtb.bmj.com/content/42/12/89.abstract(http://dtb.bmj.com/content/42/12/89.abstract) 2004;42:89–93.

Appendix B-6: Benzodiazepine tapering. In: Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. National Opioid Use Guideline Group. 2010. http://nationalpaincentre.mcmaster.ca/opioid/cgop_b_app_b06.html. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Noyes Jr R, Garvey MJ, Cook BL, Perry PJ. Benzodiazepine withdrawal: a review of the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49:382–9.

Drug and alcohol withdrawal clinical practice guidelines. NSW Government. 2008. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/mhdao/Pages/pubs-guidelines.aspx. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

O’Connor K, Marchand A, Brousseau L, Aardema F, Mainguy N, Landry P, et al. Cognitive-behavioural, pharmacological and psychosocial predictors of outcome during tapered discontinuation of benzodiazepine. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2008;15:1–14.

Onyett SR. The benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome and its management. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39:160–3.

Onyett SR, Turpin G. Benzodiazepine withdrawal in primary care: a comparison of behavioural group training and individual sessions. Behav Psychother. 1988;16:297–312.

Otto MW, Hong JJ, Safren SA. Benzodiazepine discontinuation difficulties in panic disorder: conceptual model and outcome for cognitive-behavior therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:75–80.

Otto MW, McHugh RK, Simon NM, Farach FJ, Worthington JJ, Pollack MH. Efficacy of CBT for benzodiazepine discontinuation in patients with panic disorder: further evaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:720–7.

Otto MW, Pollack MH, Meltzer-Brody S, Rosenbaum JF. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for benzodiazepine discontinuation in panic disorder patients. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1992;28:123–30.

Otto MW, Pollack MH, Sachs GS, Reiter SR, Meltzer-Brody S, Rosenbaum JF. Discontinuation of benzodiazepine treatment: efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1485–90.

Oude Voshaar RC, Couvee JE, Balkom AJ, Mulder PG, Zitman FG. Strategies for discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine use: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:213–20.

Oude Voshaar RC, Gorgels WJ, Mol AJ, Balkom AJ, Lisdonk EH, Breteler MH, et al. Tapering off long-term benzodiazepine use with or without group cognitive-behavioural therapy: three-condition, randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:498–504.

Parr JM, Kavanagh DJ, Cahill L, Mitchell G, Young RM. Effectiveness of current treatment approaches for benzodiazepine discontinuation: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2009;104:13–24.

Pat-Horenczyk R, Hacohen D, Herer P, Lavie P. The effects of substituting zopiclone in withdrawal from chronic use of benzodiazepine hypnotics. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1998;140:450–7.

Pecknold JC. Discontinuation reactions to alprazolam in panic disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27 Suppl 1:155–70.

Peles E, Hetzroni T, Bar-Hamburger R, Adelson M, Schreiber S. Melatonin for perceived sleep disturbances associated with benzodiazepine withdrawal among patients in methadone maintenance treatment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Addiction. 2007;102:1947–53.

Petrovic M, Mariman A, Warie H, Afschrift M, Pevernagie D. Is there a rationale for prescription of benzodiazepines in the elderly? Review of the literature. Acta Clin Belg. 2003;58:27–36.

Poyares DR, Guilleminault C, Ohayon MM, Tufik S. Can valerian improve the sleep of insomniacs after benzodiazepine withdrawal? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:539–45.

Raju B, Meagher D. Patient-controlled benzodiazepine dose reduction in a community mental health service. Ir J Psychol Med. 2005;22:42–5.

Rickels K, DeMartinis N, García-España F, Greenblatt DJ, Mandos LA, Rynn M. Imipramine and buspirone in treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder who are discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1973–9.

Rickels K, Schweizer E, García-España F, Case G, DeMartinis N, Greenblatt D. Trazodone and valproate in patients discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy: effects on withdrawal symptoms and taper outcome. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1999;141:1–5.

Rickels K, DeMartinis N, Rynn M, Mandos L. Pharmacologic strategies for discontinuing benzodiazepine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19 Suppl 2:12S–6S.

Romach MK, Kaplan HL, Busto UE, Somer G, Sellers EM. A controlled trial of ondansetron, a 5-HT3 antagonist, in benzodiazepine discontinuation. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;18:121–31.

Roth SM. Anxiety disorders and the use and abuse of drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50 Suppl 11:30–5.

Roy-Byrne PP, Sullivan MD, Cowley DS, Ries RK. Adjunctive treatment of benzodiazepine discontinuation syndromes: a review. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27 Suppl 1:143–53.

Roy-Byrne PP, Cowley DS. The use of benzodiazepines in the workplace. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1990;22:461–5.

Roy-Byrne PP, Hommer D. Benzodiazepine withdrawal: overview and implications for the treatment of anxiety. Am J Med. 1988;84:1041–52.

Rynn M, García-España F, Greenblatt DJ, Mandos LA, Schweizer E, Rickels K. Imipramine and buspirone in patients with panic disorder who are discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:505–8.

Sanchez-Craig M, Cappell H, Busto U, Kay G. Cognitive-behavioural treatment for benzodiazepine dependence: a comparison of gradual versus abrupt cessation of drug intake. Br J Addict. 1987;82:1317–27.

Saul PA, Korlipara K, Presley P. A randomised, multicentre, double-blind, comparison of atenolol and placebo in the control of benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms. Acta Ther. 1989;15:117–23.

Schweizer E, Rickels K. Benzodiazepine dependence and withdrawal: a review of the syndrome and its clinical management. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1998;393:95–101.

Schweizer E, Rickels K. Failure of buspirone to manage benzodiazepine withdrawal. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:1590–2.

Schweizer E, Rickels K, Case WG, Greenblatt DJ. Carbamazepine treatment in patients discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy: effects on withdrawal severity and outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:448–52.

Schweizer E, Rickels K, Case WG, Greenblatt DJ. Long-term therapeutic use of benzodiazepines II: effects of gradual taper. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:908–15.

Schweizer E, Case WG, García-España F, Greenblatt DJ, Rickels K. Progesterone co-administration in patients discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine therapy: effects on withdrawal severity and taper outcome. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1995;117:424–9.

Shapiro CM, Sherman D, Peck DF. Withdrawal from benzodiazepines by initially switching to zopiclone. Eur Psychiatry. 1995;10 Suppl 3:145S–51S.

Sloan E. Medication and substance use: keeping insomnia treatment safe. Insomnia Rounds. 2013;2:1–6.

Smith AJ, Tett SE. Improving the use of benzodiazepines–is it possible? A non-systematic review of interventions tried in the last 20 years. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:321.

Spiegel DA. Psychological strategies for discontinuing benzodiazepine treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19 Suppl 2:17S–22S.

Stewart R, Niessen WJ, Broer J, Snijders TA, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Meyboom-De JB. General practitioners reduced benzodiazepine prescriptions in an intervention study: a multilevel application. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1076–84.

Taylor DJ, Schmidt-Nowara W, Jessop CA, Ahearn J. Sleep restriction therapy and hypnotic withdrawal versus sleep hygiene education in hypnotic using patients with insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:169–75.

Management of anxiety disorders in primary care. Therapeutics Initiative. 1997. http://www.ti.ubc.ca/newsletter/management-anxiety-disorders-primary-care. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Thirtala T, Kaur K, Karlapati SK, Lippmann S. Consider this slow-taper program for benzodiazepines. Curr Psychiatr. 2013;12:55–6.

Addressing hypnotic medicines use in primary care. National Prescribing Service. 2010. http://www.nps.org.au/publications/health-professional/nps-news/2010/nps-news-67. Accessed 31 Mar 2014.

Tyrer P, Ferguson B, Hallström C, Michie M, Tyrer S, Cooper S, et al. A controlled trial of dothiepin and placebo in treating benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:457–61.

Tyrer PJ, Seivewright N. Identification and management of benzodiazepine dependence. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60 Suppl 2:41–6.

Udelman HD, Udelman DL. Concurrent use of buspirone in anxious patients during withdrawal from alprazolam therapy. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:46–50.

van de Steeg-van Gompel CH, Wensing M, De Smet PA. Implementation of a discontinuation letter to reduce long-term benzodiazepine use: a cluster randomized trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:105–14.

Vicens C, Fiol F, Llobera J, Campoamor F, Mateu C, Alegret S, et al. Withdrawal from long-term benzodiazepine use: randomised trial in family practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:958–63.

Vicens C, Bejarano F, Sempere E, Mateu C, Fiol F, Socías I, et al. Comparative efficacy of two interventions to discontinue long-term benzodiazepine use: cluster randomised controlled trial in primary care. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204:471–9.

Vissers FH, Knipschild PG, Crebolder HF. Is melatonin helpful in stopping the long-term use of hypnotics? a discontinuation trial. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:641–6.

Vorma H, Naukkarinen H, Sarna S, Kuoppasalmi K. Treatment of out-patients with complicated benzodiazepine dependence: comparison of two approaches. Addiction. 2002;97:851–9.

Woodward M. Hypnotics: options to help your patients stop. Aust Fam Physician. 2000;29:939–44.

Woodward M. Hypnosedatives in the elderly: a guide to appropriate use. CNS Drugs. 1999;11:263–79.

Zee P, Wang-Weigand S, Roth T. Facilitation of zolpidem discontinuation using ramelteon in subjects with chronic insomnia. Am J Addict. 2011;20:380–1.

Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Mrukowicz J, O’Connell D, Oxman AD, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328:1490.

Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Green L, Naylor CD, et al. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the Users’ Guides to patient care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:1290–6.

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, Hayward R, Cook DJ, Cook RJ. Users’ Guides to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;274:1800–4.

Oxford levels of evidence 2. Centre for Evidence Based Medicine. 2011. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653. Accessed 28 Nov 2014.

Coumou HC, Meijman FJ. How do primary care physicians seek answers to clinical questions? A literature review. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006;94:55–60.

Lewis PJ, Tully MP. The discomfort of an evidence-based prescribing decision. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:1152–8.

Swennen MH, van der Heijden GJ, Boeije HR, van Rheenen N, Verheul FJ, van der Graaf Y, et al. Doctors’ perceptions and use of evidence-based medicine: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Acad Med. 2013;88:1384–96.

Murphy AL, Fleming M, Martin-Misener R, Sketris IS, MacCara M, Gass D. Drug information resources used by nurse practitioners and collaborating physicians at the point of care in Nova Scotia. Canada: a survey and review of the literature BMC Nurs. 2006;5:5.

Kravitz RL, Bell RA. Media, messages, and medication: strategies to reconcile what patients hear, what they want, and what they need from medications. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13 Suppl 3:S5.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687.

Albrecht L, Archibald M, Arseneau D, Scott SD. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the workgroup for intervention development and evaluation research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement Sci. 2013;8:52.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Pringsheim T, Gardner DM. Dispensed prescriptions for quetiapine and other second-generation antipsychotics in Canada from 2005 to 2012: a descriptive study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2:E225–32.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review–a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10:21–34.

Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, DeCorby K, Bucknall TK, Kent B, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:33.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:738–47.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, Roberts MS, Wiese MD. The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust. 2014;201:386–9.

Curran HV, Collins R, Fletcher S, Kee SC, Woods B, Iliffe S. Older adults and withdrawal from benzodiazepine hypnotics in general practice: effects on cognitive function, sleep, mood and quality of life. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1223–37.

Acknowledgments

Melissa Helwig, Information Services Librarian, W.K. Kellogg Health Sciences Library, Dalhousie University, assisted with the literature search strategy. Chad Purcell, Luiza Radu, Scott Haslam, Melanie McIvor, and Heather Phelan, from the College of Pharmacy, Dalhousie University assisted with the parts of the research process. The Drug Evaluation Alliance of Nova Scotia (DEANS) provided funding support for this publication through Dr. Andrea Murphy. The views represented in this publication are those of the authors and not the funder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

AP, AM, and JB declare that they have no competing interests. DG is a developer of Sleepwell Nova Scotia (http://sleepwellns.ca/).

Authors’ contributions

AP and AM conceptualized, designed, and coordinated the project. AP, AM, and DG prepared the search and data collection protocol, with input from JB. AP conducted the literature searches. AP, JB, and AM were responsible for data acquisition and analysis, in collaboration with DG. AP and AM drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed critical review and feedback. AP, AM, JB, and DG had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. AP, the corresponding author, had the final responsibility to submit for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Research stages and methods for scoping review. Summarizes the methods used for this scoping review, outlining the various stages and contributions of each author.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

PRISMA checklist.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Description of articles included in review. This table displays information about the studies selected for inclusion in the review, including author, date of publication, study design, discontinuation strategies, age of participants studied, medication discontinued, key study outcomes, and Behaviour Change Wheel intervention functions employed.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Pollmann, A.S., Murphy, A.L., Bergman, J.C. et al. Deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults: a scoping review. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 16, 19 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-015-0019-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-015-0019-8