Abstract

Background

Research on the relationship between Facebook use intensity and depressive symptoms has resulted in mixed findings. In contrast, problematic Facebook use has been found to be a robust predictor of depressive symptoms. This suggests that when intense Facebook use results in a problematic usage pattern, it may indirectly predict depressive symptoms. However, this mediation pathway has never been examined. Moreover, it remains unclear whether the possible indirect relationship between Facebook use intensity and depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use is moderated by demographic (age), and personality (neuroticism and extraversion) characteristics.

Methods

To address these gaps, we conducted an online cross-sectional study (n = 210, 55% female, age range: 18–70 years old, Mage = 30.26, SD = 12.25). We measured Facebook use intensity (Facebook Intensity Scale), problematic Facebook use (Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale), depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised), and neuroticism and extraversion (Ten Item Personality Inventory).

Results

A mediation analysis revealed that problematic Facebook use fully mediates the relationship between Facebook use intensity and depressive symptoms. Moreover, a moderated mediation analysis demonstrated that this indirect relationship is especially strong among young users and users scoring high on neuroticism.

Conclusions

These findings expand our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the relationship between Facebook use intensity and depressive symptoms and describe user characteristics that act as vulnerability factors in this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Facebook is the most often used social networking site worldwide with almost 3 billion users [1]. Many of these users engage in intense Facebook use by (a) spending a lot of time on Facebook, (b) having a substantial number of friends on Facebook, and (c) feeling emotionally connected to Facebook [2,3,4]. There is a public concern that intense Facebook use may negatively impact mental health and even contributed to the recent increase in depression rates observed in society [5, 6].

A large number of studies have been conducted to examine whether this concern is justified. Some studies have focused on the intensity of Facebook usage but these studies yielded mixed evidence [7, 8]. For instance, while it has been found that the intensity of Facebook use positively predicts depressive symptoms [9, 10], other studies could not replicate this effect [11, 12]. Recent meta-analytical evidence reveals a positive association between the intensity of using social networking sites and depressive symptoms but this association is small [13].

Other studies have taken a more fine-grained approach and decomposed social networking sites usage into active and passive usage types [14,15,16,17]. Active usage encompasses activities that foster interactions with other users and is assumed to enhance mental health. Passive usage pertains to content consumption without direct communication with other users and is assumed to undermine mental health [18]. While initial studies were largely consistent with this active–passive model of social networking sites use [19], recent studies resulted in mixed findings [20], illustrating that this model should be extended [21].

Several psychological mechanisms have been proposed to explain the effect of Facebook use on depressive symptoms but one key mechanism is problematic Facebook use. Notably, a large volume of studies confirms that the intensity of Facebook use is a consistent predictor of problematic Facebook use [11, 22,23,24], whereas findings for the relationship between active and passive use of social networking sites and problematic usage of social networking sites are mixed [25,26,27].

Problematic Facebook use pertains to addictive properties of Facebook use, such as an inability to cut down on one’s time spent on Facebook or using Facebook to manage one’s mood [28]. Whereas prior research on the impact of Facebook use intensity on depression is rather mixed, problematic Facebook use has been found to be a robust predictor of depressive symptoms [29]. As such, when intense Facebook use gradually develops into problematic Facebook use [22, 30], it may result in depressive symptoms. Surprisingly, however, this mediation pathway has never been tested. Moreover, the strength of this pathway may differ across individuals but user characteristics moderating this mediation pathway have not been studied.

The present study seeks to address these gaps by testing a moderated mediation model, in which the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms is mediated by problematic Facebook use, and this indirect association is moderated by demographic (age), and personality characteristics (neuroticism and extraversion). Testing this model enhances our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the relationship between Facebook use intensity and depressive symptoms and elucidates which user populations are especially vulnerable to negative consequences of intense Facebook use. It is notable that we focused on Facebook as the social networking site under study as Facebook is still the social networking platform with most users worldwide [31]. Furthermore, since past studies suggest that women are more prone to use social networking sites excessively [32, 33] and score higher on depressive symptoms [34, 35], we added gender as a control variable in our analyses.

Below, we first describe prior research on problematic Facebook use and discuss how it may act as a mediator in the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. Next, we describe prior research on age, neuroticism and extraversion, and discuss how these user characteristics may act as vulnerability factors. At the end of the introduction, we specify our hypotheses.

The mediating role of problematic Facebook use

Problematic Facebook use is a subtype of problematic social media use that specifically focuses on addiction-like behaviours occurring on Facebook [36, 37]. Problematic Facebook use is most often assessed via the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale [28], which measures six components that are typical for substance addictions but then in the context of Facebook use: tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, salience, relapse, and mood modification [28, 38, 39]. The prevalence of problematic Facebook use poses a serious public health issue. This is reflected by a recent meta-analysis that summarized studies across 32 nations and found that 5 to 25% (depending on cut-off criteria) of users experience problematic Facebook use [40].

There is an ongoing debate among scholars [28, 41, 42] whether problematic use of Facebook and other types of digital technologies represent genuine behavioural addictions [43, 44]. This is reflected by some researchers preferring the term “Facebook addiction” [28, 45] or “Facebook use disorder” [46], while other researchers prefer terms such as “excessive Facebook use” [30], Facebook intrusion” [47], or “problematic Facebook use” [48, 49] to describe the same phenomenon. Considering that Facebook addiction is not (yet) officially recognized as a formal psychiatric disorder, we will follow the approach suggested by Panova and Carbonel [42] and use the term “problematic Facebook use”.

Intense use of Facebook may result in problematic Facebook use. Specifically, findings from two systematic reviews consistently showed that Facebook usage positively predicts problematic Facebook use [7, 22]. Moreover, seeking positive reinforcement (e.g., likes) [50] and entertainment usage of social networking sites [51] are positively associated with problematic use of social networking sites [52].

Why does intense Facebook use sometimes transform into an addiction-like usage pattern? The Online Social Regulation Theory (SOS-T) [53] states that people use social networking sites for self-regulation. It is assumed that different needs and goals (e.g., need for comparison, need for belongingness, and need for self-presentation) underlie usage of social networking sites. Fulfillment of these goals is strived for to achieve broader desired outcomes, such as increasing happiness or self-esteem. However, the SOS-T also argues that self-regulation on social networking sites does not necessarily lead to these desired end-states and can also be dysfunctional.

Additionally, Montag and colleagues [54, 55] argue that due to the Data Business Model (DBM), social networking sites, including Facebook, are designed to make people spend long periods of time on these platforms. For instance, the possibility to endlessly scroll on Facebook might lead to a state of flow and distorted time perception [56]. Experience of flow pertains to being fully immersed into an activity [57] and has been shown to be associated with problematic use of social networking sites [58]. Moreover, a personalized “newsfeed” on Facebook that displays relevant content tailored to each individual, might further encourage users to spend excessive amounts of time on Facebook. Finally, positive reinforcement derived from Facebook in the form of receiving [59] or providing [60] “likes” and “loves” activates the reward system in the brain, which is known to contribute to the maintenance of excessive usage patterns [61]. In line with this reasoning, a longitudinal study investigating the directionality between use of social networking sites and problematic use of social networking sites has found that increases in the intensity of use of social networking sites predicted problematic use of social networking sites one year later [11].

Lastly, according to the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model [62], when developing problematic and addiction-like Facebook usage patterns, one’s control over Facebook use declines and users experience negative consequences such as increases in negative affect [63], health-related issues, relational problems, and declined mental health [64]. Consistently, empirical studies found that problematic Facebook use is associated with negative outcomes including insomnia [65], stress [66], relationship dissatisfaction [67], anxiety [65], social anxiety [68, 69], and depressive symptoms [65, 69, 70].

Surprisingly, there are only two studies [71, 72] that directly investigated whether problematic use of social networking sites mediates the relationship between usage of these platforms and negative outcomes. Specifically, WeChat addiction was found to fully mediate the negative relationship between the intensity of WeChat use and academic performance [72] and social network site addiction was found to partially mediate the negative relationship between Instagram use and subjective well-being [71]. However, neither of these studies examined these relationships in the context of Facebook use.

The moderating role of age, neuroticism, and extraversion

Problematic Facebook use may mediate the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms but the strength of this mediation pathway might vary across people. Specifically, not all people are equally vulnerable towards developing problematic Facebook use when engaging in intense Facebook use. According to the SOS-T [53], individual differences impact self-regulatory goals and outcomes associated with these goals.

Regarding demographic features, being young may act as a vulnerability factor in developing problematic Facebook use. Young people already had first access to digital technologies at a very young age [73] and use social networking sites for construing their identity [74], developing a sense of belonging [75], and for comparison with others [76]. Moreover, the prefrontal cortex is only fully developed at the age of 24 [77] and incomplete development of this brain region is expressed in risky [78] and addictive behaviours [78, 79]. In the context of social networking sites, it has been found that being young predicts higher levels of problematic Facebook use [28, 64, 80, 81] but the possible moderating impact of age in the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use remains untested.

Among the core personality traits, neuroticism and extraversion have been found to be most strongly and consistently associated with use of social networking sites [82] and social networking sites addiction [83, 84]. Neuroticism pertains to frequent experiences of negative affect, moodiness, lack of emotional stability, anger, worry, frustration, and proneness to anxiety [85, 86]. Due to these features, users scoring high on neuroticism favour online communication as a less threatening alternative to face-to-face communication [87]. As such, they use social networking sites for strategic self-presentations [88] and compensation for lack of real-life social support [89]. In turn, the gratification of these social needs places neurotic users at a greater risk of developing an addiction-like dependency on social networking sites [83, 90]. Furthermore, according to the vulnerability model of neuroticism [91, 92], individuals with high levels of neuroticism are more vulnerable to develop addiction-like behaviour due to negative biases in attention and interpretation, and usage of maladaptive coping strategies [92]. Consistently, neuroticism has been found to have a significant positive relationship with different kinds of problematic usage of technologies [91] but the possible moderating impact of neuroticism in the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use remains untested.

People scoring high on extraversion are warm, assertive, gregarious, highly active, impulsive, and experience often positive emotions [85]. Moreover, extraverted individuals are reward-seeking and highly sociable, and Facebook provides ample opportunities for social interaction and active self-presentation. It has been shown that on social networking sites, extraverted individuals fulfil their needs for self-presentation [93], mood enhancement (e.g., maximization of positive affect), and social needs (e.g., connection and communication) [90]. Moreover, it has been found that extraverted individuals tend to have larger online social networks, post more status updates, and photos, engage more frequently in social activities and receive more positive feedback (e.g., likes) than introverted users [89]. In turn, positive feedback [83], and pleasurable emotions [90] derived from use of social networking sites may be associated with problematic use of social networking sites for extraverts. Consistently, prior empirical research reveals that a higher level of extraversion is positively related with problematic use of social networking sites [28, 68, 94, 95]. Furthermore, among the different types of digital technology addictions, only social networking sites addiction is associated with extraversion [84]. Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether extraversion moderates the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use.

The present study

The aim of the current study is to contribute to our understanding of the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms by examining the possible mediating role of problematic Facebook use and moderating role of age, neuroticism, and extraversion. Specifically, we will test four models. First, we will test the mediating effect of problematic Facebook use in the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. Next, we will test whether this indirect effect is moderated by age, neuroticism, and extraversion in three separate models (Fig. 1). In each moderated mediation model, we will test moderation of the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use (path a), problematic Facebook use and depressive symptoms (path b), and the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms (path c’). We have the following hypotheses:

H1

The intensity of Facebook use is positively related to depressive symptoms. Recent meta-analytical evidence reveals that the intensity of use of social networking sites (including Facebook) has a small but statistically significant positive association with depressive symptoms [13].

H2

Problematic Facebook use mediates the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. This mediation pathway has never been directly tested but studies conducted on Instagram [71] and WeChat [72] suggest this hypothesis to hold true.

H3

Age moderates the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms with the relationship being stronger for younger participants. This hypothesis has never been directly tested but it is consistent with prior research revealing a direct relation between being young and high levels of problematic Facebook use [28, 64, 80, 81].

H4

Neuroticism moderates the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms with the relationship being stronger for users scoring high on neuroticism. This hypothesis has never been directly tested but it is consistent with prior evidence revealing a direct relationship between neuroticism and problematic Facebook use [91].

H5

Extraversion moderates the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms with the relationship being stronger for users scoring high on extraversion. We expect this based on previous findings which suggest that the relationship between extraversion and problematic use of social networking sites is positive and significant [28, 68, 83, 90, 94, 95].

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling approach. The online questionnaire was distributed via universities’ mailing list and Facebook. To take part in the study, participants had to be at least 18 years old, have a Facebook account, and provide informed consent. The initial sample consisted of 228 individuals who volunteered to participate and provided informed consent, but 12 participants did not provide information regarding their age, and six participants were younger than 18. The final sample therefore consisted of 210 participants (55% female and 45% male) with an age range from 18 to 70 (Mage = 30.26, SD = 12.25). Overall, the questionnaire completion rate was very high (Facebook use intensity: 98%; Problematic Facebook use: 97%; Depressive symptoms: 96%; Age: 100%; Neuroticism: 93%; Extraversion: 93%). Most participants had obtained a bachelor’s degree (42%), followed by high school degree (30.1%), master’s degree (18.2%), trade/technical/vocational training (6.7%) and doctoral degree (2.4%). Furthermore, about half of the sample were students (53.1%) while 40.7% indicated that they were employed, 3.3% reported they were retired, and 2.9% were unemployed.Footnote 1

Procedure & materials

Upon providing informed consent, participants answered a number of demographic questions and completed a set of questionnaires. The study took place online and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Maastricht University.

Intensity of Facebook use

Facebook usage intensity was measured with the Facebook Intensity Scale [2]. It consists of eight items in total. The first six items are attitudinal questions regarding one’s emotional investment and connection with Facebook. Example items include “Facebook is part of my everyday activity” and “I feel I am part of the Facebook community”. These items were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The final two items assess the total number of friends one has on Facebook and the average amount of time one has spent on Facebook daily in the past week. The total number of friends is rated on an ordinal scale ranging from 1 (10 or less friends) to 9 (more than 400 friends) and the amount of time spent on Facebook is rated on an ordinal scale ranging from 1 (10 min or less) to 6 (more than 3 h). Before calculating a mean score across the eight items for each participant, all items were standardized because different items were measured on different scales. Higher scores on this scale indicate higher intensity of Facebook usage. Cronbach’s alpha for the Facebook intensity scale in the present study is 0.82.

Problematic Facebook use

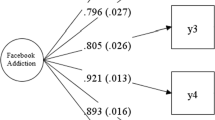

To measure problematic Facebook use we utilized the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale [28]. This scale contains six items and measures the core aspects of addiction: tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, salience, relapse, and mood modification. These items are rated on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often). For example, participants are instructed to answer how often during the last year they have “spent a lot of time thinking about Facebook or planned use of Facebook?” and “Used Facebook so much that it has had a negative impact on your job/studies?” We computed the mean score across the six items for each participant. Higher scores on this scale reflect higher problematic Facebook use. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure in the present study is 0.85.

Depressive symptoms

We measured depressive symptoms by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised (CESD-R) [96]. This scale contains 20 items, such as “I felt sad” and “I felt like a bad person”. All items were rated on a scale from 0 (Not at all or less than 1 day) to 4 (Nearly every day for 2 weeks). Respondents are instructed to answer how often they felt this way during the past two weeks. The scale score was calculated by averaging the 20 items for each participant. Higher scores on this scale indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present study is 0.94.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism was assessed by the two-item neuroticism subscale from the Ten Item Personality Inventory [97]. Participants were instructed to answer the extent to which the following traits applied to them: “Anxious, easily upset”, “Calm, emotionally stable”. Both items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). The second item was reverse-coded such that higher scores reflect higher levels of neuroticism. As both items were correlated (r = 0.52), we calculated the mean across both items.

Extraversion

Extraversion was assessed by the extraversion subscale from the Ten Item personality Inventory [97]. This subscale consists of two items: “Extraverted, enthusiastic” and “Reserved, quiet”. Respondents were instructed to answer the extent to which these traits apply to them. Both items were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). The second item was reverse coded such that higher scores reflect higher levels of extraversion. As both items were correlated (r = 0.39), we calculated the mean across both items.

Statistical approach

We used IBM SPSS (version 27) for data analysis. After computing descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the key variables, we made use of the Process Macro (version 3.5.3) [98] to examine our main hypotheses. First, using model 4, we checked whether problematic Facebook use mediated the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. To test the moderating effect of user characteristics, we fitted three separate models in the SPSS PROCESS macro, specifically model 59 [98] with age, neuroticism, or extraversion as moderator. According to Hayes [98], conditional indirect effects (moderation) are established if either path a (i.e., the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use) or path b (i.e., the relationship between problematic Facebook use and depressive symptoms) or both are influenced by the moderating variable. In all models, continuous predictors were centered and a bootstrapping procedure across 10,000 samples was utilized. Moreover, in all models, we controlled for the effects of gender on problematic use of Facebook and depressive symptoms. Gender was coded in the following way: 0 denotes males, 1 denotes females. Please note that we used the bootstrapping technique, therefore, it was not necessary to meet the assumptions with regard to the mediation model outlined by Hayes [98]. Furthermore, the variance Inflation Factors (VIF) were all below 5, indicating the absence of multicollinearity [99].

Results

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the assessed variables.

Does the intensity of Facebook use predict depressive symptoms?

To answers this question, we conducted a regression analysis predicting depressive symptoms by Facebook use intensity. The intensity of Facebook use was found to be positively related to depressive symptoms (B = 0.191, β = 0.211, SE = 0.063, p = 0.003).

Does problematic Facebook use mediate the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms?

The results showed that the overall model predicting problematic Facebook use was significant: F(2, 197) = 63.56, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.392. Intensity of Facebook use significantly and positively predicted problematic Facebook use (B = 0.706, β = 0.614, SE = 0.064, p < 0.001). The overall model predicting depressive symptoms was also significant: F(3, 196) = 16.47, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.201. Problematic Facebook use significantly and positively predicted depressive symptoms (B = 0.396, β = 0.502, SE = 0.065, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of the intensity of Facebook use on depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use was statistically significant (B = 0.279, β = 0.308, SE = 0.056, Bootstrap 95% CI: [0.175—0.396]). Finally, the direct association between the intensity of Facebook use on depressive symptoms was not significant (B = -0.088, β = -0.097, SE = 0.074, p = 0.235) reflecting full mediation (see Fig. 2).

Problematic Facebook use as a significant mediator of the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms (Controlling for Gender). Note N = 200. Regression weights are standardized. C’ is the direct effect of Facebook use intensity on Depressive symptoms; C is the total effect of Facebook use intensity on Depressive symptoms. ***p < .01

The moderating role of age

The overall model predicting problematic Facebook use was significant F (4, 195) = 37.06, p < 0.001. We found that the interaction term between the intensity of Facebook use and age significantly predicted problematic Facebook use (Table 2). To facilitate the interpretation of this moderation effect, Fig. 3 displays problematic Facebook use as a function of the intensity of Facebook use and age (1SD below the mean, 1 SD above the mean). Results from the simple slope tests indicate that the association between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use is significant for both age groups. However, the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use is stronger among younger users (B = 0.902, SE = 0.088, p < 0.001), compared to older users (B = 0.464, SE = 0.093, p < 0.001).

On the other hand, although the overall model predicting depressive symptoms was significant F(6, 193) = 11.83, p < 0.001, neither the interaction term between Facebook use intensity and age, nor between problematic Facebook use and age were significant (Table 2). Overall, age was found to moderate the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms by moderating the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use (path a). Consistently, the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use was moderated by age. The indirect effect was more pronounced among younger users (B = 0.377, SE = 0.087, Bootstrap 95% CI: [0.208, 0.553]), compared to older users (B = 0.145, SE = 0.057, Bootstrap 95% CI: [0.061, 0.285]).

The moderating role of neuroticism

Next, we examined the possible moderating effect of neuroticism (Table 3). The overall model predicting problematic Facebook use was significant: F(4, 189) = 41.92, p < 0.001. The relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use was moderated by neuroticism (B = 0.140, SE = 0.038, p < 0.001). To ease the interpretation of this interaction effect, Fig. 4 shows the predicted value of problematic Facebook use as a function of the intensity of Facebook use and neuroticism (1SD below the mean, 1SD above the mean). Simple slopes analysis revealed that the intensity of Facebook use is related to problematic Facebook use at both levels of neuroticism, but this relationship is considerably weaker for users scoring low on neuroticism (B = 0.447, SE = 0.087, p < 0.001), compared to users scoring high on neuroticism (B = 0.902, SE = 0.088, p < 0.001).

Furthermore, the overall model predicting depressive symptoms was significant as well: F(6, 187) = 17.01, p < 0.001. However, the interactions between Facebook use intensity and neuroticism and between problematic Facebook use and neuroticism were not significant (Table 3).

Overall, neuroticism was found to moderate the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms by moderating the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use (path a). Consistently, the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use was moderated by neuroticism. The indirect effect was more pronounced among users scoring high on neuroticism (B = 0.275, SE = 0.097, Bootstrap 95% CI: [0.094, 0.476]), compared to users scoring low on neuroticism (B = 0.110, SE = 0.044, Bootstrap 95% CI: [0.036, 0.209]).

The moderating role of extraversion

Finally, we tested the possible moderating effect of extraversion (Table 4). The overall model predicting problematic Facebook use was significant F(4, 189) = 33.69, p < 0.001. However, the interaction term between the intensity of Facebook use and extraversion when predicting problematic Facebook use was not significant (Table 4). Similarly, while the overall model predicting depressive symptoms was significant: F(6, 187) = 8.49, p < 0.001, the interaction terms between Facebook use intensity and extraversion and between problematic Facebook use and extraversion were not significant (Table 4). Overall, extraversion was not found to moderate the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms.

Sensitivity analysis

In the preceding analyses, we examined the role of each moderator separately. To demonstrate the robustness of our findings, we reran the aforementioned three moderation analyses controlling for the other two moderators. For example, we re-examined the moderating role of age, while controlling for the effects of neuroticism and extraversion. These sensitivity analyses confirmed our conclusions: age and neuroticism moderate the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use, whereas extraversion has no moderating effect.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to examine the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms and study the mediating and moderating mechanisms underlying and affecting this relationship. We found that problematic Facebook use fully mediated the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. Moreover, we demonstrated that age and neuroticism moderated the first stage of this mediation relationship (path a: intensity of Facebook use predicting problematic Facebook use) but not the second stage (path b: problematic Facebook use predicting depressive symptoms). Extraversion did not moderate the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. We discuss these findings in more detail below.

The mediating role of problematic Facebook use

Our first aim was to investigate whether problematic Facebook use underlies the relationship between the intensity of Facebook usage and depressive symptoms. Our results confirmed that problematic Facebook use fully mediates this relationship. This finding is line with prior research showing that intensive Facebook usage can transform into problematic usage patterns [65, 100, 101], which in turn, can lead to declines in mental health [45, 48, 70]. Moreover, our results are consistent with previous studies directly examining the mediating roles of social networking site addiction and WeChat addiction in the relationship between Instagram use and subjective well-being [71] and WeChat use and academic performance [72], respectively. However, our study extends these findings by suggesting that also on Facebook intense but non-addictive use of this social network site may gradually transform into an addictive usage pattern.

Why does problematic Facebook use mediate the relationship between intense Facebook use and depressive symptoms? According to the Online Self-Regulation Theory [53], users resort to using social networking sites to regulate themselves. However, this attempt is not always successful and can result in detrimental outcomes. As such, it is plausible that the specific goals and motivations that underlie self-regulatory use of social networking sites seem achievable to users and make them more invested in Facebook usage. This, in turn, can lead to an overreliance on Facebook and the development of problematic usage of Facebook.

Additionally, Montag and colleagues [54] argue that the Data Business Model (DBM) also plays a role in the development of problematic usage of social networking sites. Specifically, it is assumed that the medium-specific factors play an important role in the development of problematic usage behaviours. Therefore, it seems plausible that specific elements and parts of the design of Facebook make people more vulnerable to develop problematic usage patterns. For instance, the experience of flow [102] and distorted perception of time while using Facebook may contribute to problematic usage patterns [103]. Moreover, once addiction-like attachment towards digital technology (including Facebook) is being developed, users may tend to lose control over their behaviour over time which results in negative outcomes for mental health [62].

The moderating roles of age and neuroticism but not extraversion

The second aim of the present study was to test whether the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms via problematic Facebook use was conditional on age, neuroticism, and extraversion. With regard to age, we found that being older acts as a protective factor as the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use is less strong compared to younger users. Interestingly, we were unable to find a moderating impact of age on the second stage of the mediation pathway connecting problematic Facebook use to depressive symptoms. As such, this suggests that age only plays a protective role at the onset of developing addiction-like problematic behaviours on Facebook but does not protect the user from developing depressive symptoms once the user is already engaging in problematic Facebook use.

Our results corroborate previous studies showing that younger users have heightened risks to develop technology addictions [104, 105] including problematic Facebook use [28, 64]. Our findings also support the SOS-T model [53], which maintains that individual differences influence self-regulatory goals on social networking sites. As such, our finding specify for whom self-regulation on social networking sites may become dysfunctional. A number of reasons may explain the observed relationships. First, compared to older adults, young people may engage in more social comparisons on Facebook which may results in more intense Facebook use for reasons of impression management [76]. Second, it has been shown that young users who experience a higher need to belong are at greater risk of developing problematic usage patterns [106]. Alternatively, the present finding suggesting that young users are especially vulnerable towards developing problematic Facebook use may also be rooted in incomplete development of the prefrontal cortex which makes individuals vulnerable towards developing addiction-like symptoms [78, 107, 108].

We also found that neuroticism is a vulnerability factor as it moderates the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. Specifically, we demonstrated that higher levels of neuroticism amplify the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and problematic Facebook use. Similar to age, neuroticism did not moderate the relationship between problematic Facebook use and depressive symptoms.

While previous research has consistently linked higher levels of neuroticism with different types of digital addictions [91, 109], our study has taken this research one step further by showing that neuroticism not only directly predicts problematic Facebook use, but also interacts with Facebook usage intensity in fostering problematic Facebook usage. Overall, our findings fit well into the vulnerability model of neuroticism [91, 92] which argues that higher levels of neuroticism presents an important risk factor for developing common mental health disorders. Moreover, our results complement the SOS-T model [53] which posits that especially users with emotion regulation difficulties are prone to resort to dysfunctional self-regulation via social networking sites [16]. Here, we again clarify the specific subset of users for whom self-regulation on social networking sites is associated with detriments. As such, while neurotic users may turn to these platforms to regulate their need for self-presentation [88] or satisfy their need to belong [93], they may fail doing in an efficient manner resulting in problematic social networking sites use. This is consistent with research showing a negative relationship between neuroticism and emotion regulation capacity [110].

Finally, we were unable to find evidence for a moderating impact of extraversion on the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms. Previous research on the relationship between extraversion and digital technologies suggested a positive link between problematic Facebook use and extraversion [28, 68, 94, 95]. However, our results suggest that extraversion is neither a vulnerability nor a protective factor in the indirect relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms through problematic Facebook use. Given, that extraverts tend to have larger offline social networks [111], are satisfied with their offline social relationships [112], and use healthy coping strategies [113, 114], it is plausible to argue that they satisfy their needs for self-presentation and rewarding experiences both online and offline. As a result, extraverts are not dependent on social networking sites such as Facebook to regulate themselves and are not more prone to develop addictive patterns following intense Facebook use.

Implications and limitations

Our findings are useful for counsellors, public health policy makers, and researchers. We have demonstrated that (non-problematic) intense Facebook use may result in problematic Facebook usage patterns, which, in turn, undermine users’ mental health. Moreover, we have shown that this indirect effect is especially outspoken among young users and users with high levels of neuroticism. Counsellors can make use of these findings to better identify and support the most vulnerable user populations. Moreover, they could rely on our findings when designing interventions, as the present study suggest that intense Facebook use is especially detrimental for mental health when it results in addictive usage patterns. Similarly, public health policy makers could make use of our findings when creating prevention strategies and campaigns by warning especially young users and users high in neuroticism of the possible dangers of excessive Facebook use and associated addiction symptoms. Moreover, also researchers who examine the relationship between usage of social networking sites and mental health might benefit from our findings. Specifically, our study directly responds to a call made by Boer and colleagues [11] to identify groups of users for whom usage of social networking sites develops into problematic usage patterns. However, future studies are needed to further examine problematic Facebook use as a key mechanism underlying the relationship between Facebook use intensity and mental health, and to pay more attention to individual differences that either protect or make users more vulnerable towards negative outcomes of intense Facebook use. Additionally, future studies should study a broad range of different social networking sites and their unique features when examining the relationship between use of social networking sites and problematic usage patterns. The present study provides evidence that intensive Facebook use may turn into problematic usage. Moreover, this was also found for Instagram [71] and WeChat [72] in prior studies, but more evidence is necessary to identify the platforms for which usage is most likely to turn into problematic usage patterns.

The present study has also a number of limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings of this study. First, we used a convenience sampling technique and Facebook users with higher education degrees were overrepresented. Future studies would benefit from recruiting bigger and more diverse samples. Second, while the sample size of the present study was modest, we ran a sensitivity analysis to check the range of effect sizes (two-tailed correlation) that our study design could detect reliably (80% power), given our sample size (n = 210) and α = 0.05. The results show that our study design is sufficiently powered to detect effect sizes from |p| 0.19 and above, i.e., small to medium-sized effects (and larger) as specified by Cohen [115]. This is consistent with the effect sizes observed in previous research on the relationship between the constructs under examination [48, 116, 117]. However, future studies using larger sample sizes are necessary to replicate the current findings. Such larger sample sizes would also allow modelling the data with a structural equation modelling approach rather than the PROCESS approach used in the present study. Third, in the present study, we focused on Facebook. While Facebook still has the most users worldwide [118], other platforms such as TikTok and Instagram are becoming increasingly popular, especially among younger users [31]. Future studies are needed to examine whether our findings replicate across these other platforms, and to test whether our findings also hold when assessing social networking sites use in general without specifying specific platforms. Fourth, future studies need to replicate our findings by using different conceptualizations or subtypes of social networking sites use (e.g., active and passive usage) which may be differentially related to mental health outcomes [19] and problematic social networking site usage [26]. Fifth, in this study we made use of the Ten Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) [97]. While the neuroticism and extraversion dimensions of the TIPI have been shown to have good convergence with the corresponding dimensions of the International Personality Item Pool Neo-120 and Big Five Inventory-2 [119], future research needs to replicate our findings using longer measures of extraversion and neuroticism. Furthermore, our study was cross-sectional. As such, strong causal claims cannot be made. While we examined the mediating role of problematic Facebook use in the relationship between Facebook use intensity and depressive symptoms, alternative models, including bi-directional relationships between these constructs are also possible [120]. Future studies using longitudinal or experimental designs are needed to clarify the temporal and causal relationships between the intensity of Facebook use, problematic Facebook use and depressive symptoms. Finally, future research using clinical samples is needed to advance our understanding of social networking sites usage in a clinical context.

Conclusions

In the present study, we have demonstrated that the relationship between the intensity of Facebook use and depressive symptoms is mediated by problematic Facebook use. Moreover, we have shown that this indirect relationship is moderated by age and neuroticism. Overall, our results suggest that intense Facebook use can result in adverse outcomes once it turns into a problematic (addictive) usage pattern, which is especially likely to happen among users who are young and score high on neuroticism.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Moreover, upon publication, the dataset will be made accessible on dataverseNL.

Notes

The dataset along the code will be accessible on dataverseNL.

Abbreviations

- The I-Pace model:

-

The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model

- SPSS:

-

Statistical product and service solutions

References

Tankovska H. Global social networks ranked by number of users 2021; 2021. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2007;12(4):1143–68.

Orosz G, Tóth-Király I, Bőthe B. Four facets of Facebook intensity—the development of the multidimensional Facebook intensity scale. Personal Individ Differ. 2016;100:95–104.

VandenAbeele MMP, Antheunis ML, Pollmann MMH, Schouten AP, Liebrecht CC, van der Wijst PJ, et al. Does Facebook Use predict college students’ social capital? A replication of Ellison, Steinfield, and Lampe’s (2007) Study using the original and more recent measures of facebook use and social capital. Commun Stud. 2018;69(3):272–82.

O’Connell M. The deliberate awfulness of social media. The New Yorker; 2018 [cited 2021 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/the-deliberate-awfulness-of-social-media

Orlowski J. We need to rethink social media before it’s too late. We’ve accepted a Faustian bargain. The Guardian; 2020 [cited 2021 Jul 16]. Available from: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/sep/27/social-dilemma-media-facebook-twitter-society

Frost RL, Rickwood DJ. A systematic review of the mental health outcomes associated with Facebook use. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;76:576–600.

Kross E, Verduyn P, Sheppes G, Costello CK, Jonides J, Ybarra O. Social media and well-being: pitfalls, progress, and next steps. Trends Cogn Sci. 2021;25(1):55–66.

Brailovskaia J, Ströse F, Schillack H, Margraf J. Less Facebook use: more well-being and a healthier lifestyle? An experimental intervention study. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;1(108):106332.

Steers MLN, Wickham RE, Acitelli LK. Seeing everyone else’s highlight reels: how Facebook usage is linked to depressive symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2014;33(8):701–31.

Boer M, Stevens GWJM, Finkenauer C, de Looze ME, van den Eijnden RJJM. Social media use intensity, social media use problems, and mental health among adolescents: Investigating directionality and mediating processes. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;116. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85098846036&doi=10.1016%2fj.chb.2020.106645&partnerID=40&md5=1364c3b8706575b0ffc0e73a44df9a81

Jelenchick LA, Eickhoff JC, Moreno MA. “Facebook depression?” Social networking site use and depression in older adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(1):128–30.

Cunningham S, Hudson CC, Harkness K. Social media and depression symptoms: a meta-analysis. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2021;49(2):241–53.

Escobar-Viera CG, Shensa A, Bowman ND, Sidani JE, Knight J, James AE, et al. Passive and active social media use and depressive symptoms among united states adults. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21(7):437–43.

Verduyn P, Lee DS, Park J, Shablack H, Orvell A, Bayer J, et al. Passive facebook usage undermines affective well-being: experimental and longitudinal evidence. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2015;144(2):480–8.

Ozimek P, Bierhoff HW. All my online-friends are better than me – three studies about ability-based comparative social media use, self-esteem, and depressive tendencies. Behav Inf Technol. 2019;39(10):1110–23.

Krasnova H, Widjaja T, Buxmann P, Wenninger H, Benbasat I. Why following friends can hurt you: an exploratory investigation of the effects of envy on social networking sites among college-age users. Inf Syst Res. 2015;26(3):585–605.

Verduyn P, Gugushvili N, Kross E. The impact of social network sites on mental health: distinguishing active from passive use. World Psychiatry; 2019.

Verduyn P, Ybarra O, Résibois M, Jonides J, Kross E. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2017;11(1):274–302.

Valkenburg PM, van Driel II, Beyens I. The associations of active and passive social media use with well-being: a critical scoping review. New Media Soc. 2021;31:14614448211065424.

Verduyn P, Gugushvili N, Kross E. Do social networking sites influence well-being-the extended active -passive model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214211053637.

Ryan T, Chester A, Reece J, Xenos S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: a review of Facebook addiction. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(3):133–48.

Fuster H, Chamarro A, Oberst U. Fear of missing out, online social networking and mobile phone addiction: a latent profile approach. Aloma Rev Psicol Ciènc Educ Esport. 2017;35(1):22–30.

Müller KW, Dreier M, Beutel ME, Duven E, Giralt S, Wölfling K. A hidden type of internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescents. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;1(55):172–7.

Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. The relationship between active and passive Facebook use, Facebook flow, depression symptoms and Facebook Addiction: a three-month investigation. J Affect Disord Rep. 2022;1(10):100374.

Fioravanti G, Casale S. The active and passive use of Facebook: measurement and association with Facebook addiction. 2020;176–82

Keum BT, Wang YW, Callaway J, Abebe I, Cruz T, O’Connor S. Benefits and harms of social media use: A latent profile analysis of emerging adults. Curr Psychol; 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 17]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03473-5

Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):501–17.

Huang C. A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;0020764020978434.

Guedes E, Sancassiani F, Carta MG, Campos C, Machado S, King ALS, et al. Internet addiction and excessive social networks use: what about Facebook? Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health CP EMH. 2016;28(12):43–8.

Kemp S. Digital 2022: Global Overview Report. DataReportal–Global Digital Insights; 2022 [cited 2022 Jul 27]. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report

Spilková J, Chomynová P, Csémy L. Predictors of excessive use of social media and excessive online gaming in Czech teenagers. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):611–9.

Su W, Han X, Yu H, Wu Y, Potenza MN. Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;113. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85088821651&doi=10.1016%2fj.chb.2020.106480&partnerID=40&md5=5c2ef273d5f3b6c1b7554ecec5376ca6

Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(5):1061–72.

Thayer JF, Rossy LA, Ruiz-Padial E, Johnsen BH. Gender differences in the relationship between emotional regulation and depressive symptoms. Cogn Ther Res. 2003;27(3):349–64.

Balcerowska JM, Bereznowski P, Biernatowska A, Atroszko PA, Pallesen S, Andreassen CS. Is it meaningful to distinguish between Facebook addiction and social networking sites addiction? Psychometric analysis of Facebook addiction and social networking sites addiction scales. Curr Psychol. 2020; Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85078466429&doi=10.1007%2fs12144-020-00625-3&partnerID=40&md5=bf49248427da1249f9416f8311a1ea95

D Griffiths M. Social networking addiction: emerging themes and issues. J Addict Res Ther; 2013 [cited 2021 Jul 17]; 04(05). Available from: https://www.omicsonline.org/social-networking-addiction-emerging-themes-and-issues-2155-6105.1000e118.php?aid=22152

Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. 2017;64:287–93.

Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use. 2005;10(4):191–7.

Cheng C, Lau YC, Chan L, Luk JW. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict Behav. 2021;117:106845.

Kardefelt-Winther D, Heeren A, Schimmenti A, van Rooij A, Maurage P, Carras M, et al. How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction. 2017;112(10):1709–15.

Panova T, Carbonell X. Is smartphone addiction really an addiction? J Behav Addict. 2018;7(2):252–9.

Billieux J, Philippot P, Schmid C, Maurage P, Mol JD, der Linden MV. Is dysfunctional use of the mobile phone a behavioural addiction? Confronting symptom-based versus process-based approaches. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2015;22(5):460–8.

Billieux J, Schimmenti A, Khazaal Y, Maurage P, Heeren A. Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(3):119–23.

Brailovskaia J, Schillack H, Margraf J. Facebook addiction disorder in Germany. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2018;21(7):450–6.

Montag C, Wegmann E, Sariyska R, Demetrovics Z, Brand M. How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of Internet use disorders and what to do with “smartphone addiction”? J Behav Addict. 2021;9(4):908–14.

Błachnio A, Przepiórka A, Pantic I. Internet use, Facebook intrusion, and depression: results of a cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(6):681–4.

Marino C, Gini G, Vieno A, Spada MM. A comprehensive meta-analysis on problematic Facebook Use. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;83:262–77.

Satici SA, Uysal R. Well-being and problematic Facebook use. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;49:185–90.

Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Daspe MÈ, Lussier Y, Giroux-Benoît C. For the love of being liked: a moderated mediation model of attachment, likes-seeking behaviors, and problematic Facebook use. Addict Res Theory. 2020;28(5):397–405.

Brailovskaia J, Bierhoff HW, Rohmann E, Raeder F, Margraf J. The relationship between narcissism, intensity of Facebook use, Facebook flow and Facebook addiction. Addict Behav Rep; 2020. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2020-13676-001&site=ehost-live

Zhao L. The impact of social media use types and social media addiction on subjective well-being of college students: a comparative analysis of addicted and non-addicted students. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2021;1(4):100122.

Ozimek P, Förster J. The social online-self-regulation-theory. J Media Psychol. 2021;33(4):181–90.

Montag C, Lachmann B, Herrlich M, Zweig K. Addictive features of social media/messenger platforms and freemium games against the background of psychological and economic theories. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2612.

Montag C, Hegelich S, Sindermann C, Rozgonjuk D, Marengo D, Elhai JD. On corporate responsibility when studying social media use and well-being. Trends Cogn Sci. 2021;25(4):268–70.

Hancock PA, Kaplan AD, Cruit JK, Hancock GM, MacArthur KR, Szalma JL. A meta-analysis of flow effects and the perception of time. Acta Psychol Amst. 2019;1(198):102836.

Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The classic work on how to achieve happiness; 2002 [cited 2021 Jul 15]. Available from: https://books.google.ge/books/about/Flow.html?id=rTUB9tEDyfgC&redir_esc=y

Brailovskaia J, Teichert T. “I like it” and “I need it”: relationship between implicit associations, flow, and addictive social media use. Comput Hum Behav. 2020;1(113):106509.

Sherman LE, Payton AA, Hernandez LM, Greenfield PM, Dapretto M. The power of the like in adolescence: effects of peer influence on neural and behavioral responses to social media. Psychol Sci. 2016;27(7):1027–35.

Sherman LE, Hernandez LM, Greenfield PM, Dapretto M. What the brain ‘Likes’: neural correlates of providing feedback on social media. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2018;13(7):699–707.

Roberts AJ, Koob GF. The neurobiology of addiction. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(2):101–6.

Brand M, Wegmann E, Stark R, Müller A, Wölfling K, Robbins TW, et al. The interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model for addictive behaviors: update, generalization to addictive behaviors beyond internet-use disorders, and specification of the process character of addictive behaviors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;1(104):1–10.

Brand M, Young KS, Laier C, Wölfling K, Potenza MN. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: an Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;1(71):252–66.

Andreassen CS. Online social network site addiction: a comprehensive review. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2(2):175–84.

Koc M, Gulyagci S. Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: the role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology Behav Soc Netw. 2013;16(4):279–84.

Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. Facebook addiction disorder (FAD) among German students—a longitudinal approach. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):1–15.

Elphinston RA, Noller P. Time to face It! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(11):631–5.

Atroszko PA, Balcerowska JM, Bereznowski P, Biernatowska A, Pallesen S, Andreassen CS. Facebook addiction among Polish undergraduate students: validity of measurement and relationship with personality and well-being. Comput Hum Behav. 2018;85:329–38.

Foroughi B, Iranmanesh M, Nikbin D, Hyun SS. Are depression and social anxiety the missing link between Facebook addiction and life satisfaction? The interactive effect of needs and self-regulation. Telemat Inform. 2019;43:101247.

Hong FY, Huang DH, Lin HY, Chiu SL. Analysis of the psychological traits, Facebook usage, and Facebook addiction model of Taiwanese university students. Telemat Inform. 2014;31(4):597–606.

Donnelly E. Depression among Users of Social Networking Sites (SNSs): the role of SNS addiction and increased usage. J Addict Prev Med; 2017 [cited 2021 Jul 18];02(01). Available from: https://www.elynsgroup.com/journal/j-add-pre-med/article/depression-among-users-of-social-networking-sites-snss-the-role-of-sns-addiction-and-increased-usage

Li Y, Sallam MH, Yinghua Y. The impact of WeChat use intensity and addiction on academic performance. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 2019;47(1):1–7.

Wang HY, Sigerson L, Cheng C. Digital nativity and information technology addiction: age cohort versus individual difference approaches. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;1(90):1–9.

Longobardi C, Settanni M, Fabris MA, Marengo D. Follow or be followed: Exploring the links between Instagram popularity, social media addiction, cyber victimization, and subjective happiness in Italian adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;1(113):104955.

Pang H. Examining associations between university students’ mobile social media use, online self-presentation, social support and sense of belonging. Aslib J Inf Manag. 2020;72(3):321–38.

Ozimek P, Bierhoff HW. Facebook use depending on age: the influence of social comparisons. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;1(61):271–9.

Arain M, Haque M, Johal L, Mathur P, Nel W, Rais A, et al. Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:449–61.

Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(2):189–99.

Choi SW, Kim HS, Kim GY, Jeon Y, Park SM, Lee JY, et al. Similarities and differences among Internet gaming disorder, gambling disorder and alcohol use disorder: a focus on impulsivity and compulsivity. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(4):246–53.

Błachnio A, Przepiorka A. Personality and positive orientation in Internet and Facebook addiction. An empirical report from Poland. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;59:230–6.

Jafarkarimi H, Sim ATH, The Department of Information Systems, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia, Saadatdoost R, the Department of Computer and Information Technology, Parand Branch, Islamic Azad University, Parand, Iran, Hee JM, et al. Facebook Addiction among Malaysian Students. Int J Inf Educ Technol. 2016;6(6):465–9.

Amichai-Hamburger Y, Vinitzky G. Social network use and personality. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(6):1289–95.

Marengo D, Poletti I, Settanni M. The interplay between neuroticism, extraversion, and social media addiction in young adult Facebook users: Testing the mediating role of online activity using objective data. Addict Behav. 2020;102. Available from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85074419591&doi=10.1016%2fj.addbeh.2019.106150&partnerID=40&md5=833482e623a3d386fdc87cba7ba0107e

Wang CW, Ho RTH, Chan CLW, Tse S. Exploring personality characteristics of Chinese adolescents with internet-related addictive behaviors: trait differences for gaming addiction and social networking addiction. Addict Behav. 2015;1(42):32–5.

Costa PT, McCrae RR. Four ways five factors are basic. Personal Individ Differ. 1992;13(6):653–65.

Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol Assess. 1992;4(1):26–42.

Amichai-Hamburger Y, Wainapel G, Fox S. “On the internet no one knows i’m an introvert”: extroversion, neuroticism, and internet interaction. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2002;5(2):125–8.

Michikyan M, Subrahmanyam K, Dennis J. Can you tell who I am? Neuroticism, extraversion, and online self-presentation among young adults. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;1(33):179–83.

Shen J, Brdiczka O, Liu J. A study of Facebook behavior: What does it tell about your neuroticism and extraversion? Comput Hum Behav. 2015;1(45):32–8.

Chen A, Roberts N. Connecting personality traits to social networking site addiction: the mediating role of motives. Inf Technol People. 2019;33(2):633–56.

Marciano L, Camerini AL, Schulz PJ. Neuroticism in the digital age: A meta-analysis. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2020;2:100026.

Ormel J, Jeronimus BF, Kotov R, Riese H, Bos EH, Hankin B, et al. Neuroticism and common mental disorders: meaning and utility of a complex relationship. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(5):686–97.

Seidman G. Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: how personality influences social media use and motivations. Personal Individ Differ. 2013;54(3):402–7.

Biolcati R, Mancini G, Pupi V, Mugheddu V. Facebook addiction: onset predictors. J Clin Med. 2018;7(6):118–118.

Nikbin D, Iranmanesh M, Foroughi B. Personality traits, psychological well-being, Facebook addiction, health and performance: testing their relationships. Behav Inf Technol. 2021;40(7):706–22.

Eaton WW, Smith C, Ybarra M, Muntaner C, Tien A. Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). In: The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults, vol. 3. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2004. pp. 363–77.

Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J Res Personal. 2003;37(6):504–28.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, second edition: a regression-based approach. Guilford Publications; 2017. pp. 713.

Daoud JI. Multicollinearity and regression analysis. J Phys Conf Ser. 2017;949(1):012009.

Baturay MH, Toker S. Self-esteem shapes the impact of GPA and general health on Facebook addiction: a mediation analysis. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2017;35(5):555–75.

Cudo A, Torój M, Demczuk M, Francuz P. Dysfunction of self-control in facebook addiction: impulsivity is the key. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91(1):91–101.

Mauri M, Cipresso P, Balgera A, Villamira M, Riva G. Why Is Facebook so successful? Psychophysiological measures describe a core flow state while using Facebook. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14(12):723–31.

Turel O, Brevers D, Bechara A. Time distortion when users at-risk for social media addiction engage in non-social media tasks. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;97:84–8.

Csibi S, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z, Szabo A. Analysis of problematic smartphone use across different age groups within the ‘components model of addiction.’ Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021;19(3):616–31.

Hawi NS, Samaha M, Griffiths MD. Internet gaming disorder in Lebanon: relationships with age, sleep habits, and academic achievement. J Behav Addict. 2018;7(1):70–8.

Wang P, Zhao M, Wang X, Xie X, Wang Y, Lei L. Peer relationship and adolescent smartphone addiction: the mediating role of self-esteem and the moderating role of the need to belong. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):708–17.

Chambers RA, Taylor JR, Potenza MN. Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: a critical period of addiction vulnerability. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1041–52.

Gladwin TE, Figner B, Crone EA, Wiers RW. Addiction, adolescence, and the integration of control and motivation. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2011;1(4):364–76.

Bowden-Green T, Hinds J, Joinson A. Understanding neuroticism and social media: a systematic review. Personality Individ Differ. 2021;168:110344

Barańczuk U. The five factor model of personality and social support: a meta-analysis. J Res Personal. 2019;1(81):38–46.

Pollet TV, Roberts SGB, Dunbar RIM. Extraverts have larger social network layers: but do not feel emotionally closer to individuals at any layer. J Individ Differ. 2011;32(3):161–9.

Tov W, Nai ZL, Lee HW. Extraversion and agreeableness: divergent routes to daily satisfaction with social relationships. J Pers. 2016;84(1):121–34.

Amirkhan JH, Risinger RT, Swickert RJ. Extraversion: a “hidden” personality factor in coping? J Pers. 1995;63(2):189–212.

Kokkonen M, Pulkkinen L. Extraversion and Neuroticism as antecedents of emotion regulation and dysregulation in adulthood. Eur J Personal. 2001;15(6):407–24.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 1988. p. 567.

Przepiorka A, Błachnio A, Díaz-Morales JF. Problematic Facebook use and procrastination. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;1(65):59–64.

Simoncic TE, Kuhlman KR, Vargas I, Houchins S, Lopez-Duran NL. Facebook use and depressive symptomatology: investigating the role of neuroticism and extraversion in youth. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;40:1–5.

Statista. Biggest social media platforms 2022. Statista; 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Sleep CE, Lynam DR, Miller JD. A comparison of the validity of very brief measures of the big five/five-factor model of personality. Assessment. 2021;28(3):739–58.

Stanković M, Nešić M, Čičević S, Shi Z. Association of smartphone use with depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, and internet addiction. Empirical evidence from a smartphone application. Personal Individ Differ. 2021;168:110342.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NG: Data analysis, Paper writing, Paper revising, KT: Paper revising, Data checking, Supervision. RR: Paper revising, Supervision, PV: Data collection, Paper revising, Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Maastricht University, code: 161_03_02_2016_S16. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the start of the study. The participation in the study was voluntary. The researchers assured anonymity and confidentiality of participants’ data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gugushvili, N., Täht, K., Ruiter, R.A.C. et al. Facebook use intensity and depressive symptoms: a moderated mediation model of problematic Facebook use, age, neuroticism, and extraversion. BMC Psychol 10, 279 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00990-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00990-7