Abstract

Background

Sleep habits are related to children's behavior, emotions, and cognitive functioning. A strong relationship exists between sleep habits and behavioral problems. However, precisely which sleep habits are associated with behavioral problems remains unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to clarify the relationship between sleep habits and behavioral problems in early adolescence.

Methods

This study used data from a larger longitudinal research, specifically, data from the year 2021. First-year junior high school students (12–14 years) in Japan were surveyed; their parents (N = 1288) completed a parent-report questionnaire. The main survey items were subject attributes, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).

Results

Of the 652 valid responses received, 604 individuals who met the eligibility criteria (no developmental disability in the child and completion of all survey items) were included in the analysis. To examine the relationship between sleep habits and behavioral problems, logistic regression analysis using the inverse weighted method with propensity score was conducted with sleep habits (sleep quality, time to fall asleep, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep difficulty, use of sleeping pills, difficulty waking during the day, and sleep disturbances) as explanatory variables and behavioral problems (overall difficulty in SDQ) as objective variables. The propensity score was calculated by employing the logistic regression using the inverse weighted method based on propensity scores. Propensity scores were calculated based on gender, family structure, household income, and parental educational background. The results showed that behavioral problems tended to be significantly higher in the group at risk for sleep quality, sleep difficulties, daytime arousal difficulties, and sleep disturbances than in the group with no risk.

Conclusion

The results suggest that deterioration in sleep quality, sleep difficulties, daytime arousal difficulties, and sleep disturbances may increase the risk of behavioral problems in adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sleep is a biological process necessary for survival and critical to healthy living [1]. It plays an important role in brain function and impacts systemic physiology, metabolism, appetite regulation, immune system functioning, and hormonal and cardiovascular system function [2]. A key component of a healthy lifestyle is adequate sleep at appropriate times, devoid of sleep disturbances [3,4,5]. Sleep duration, quality of sleep, sleep timing and regularity, and absence of sleep disturbances or disorders influence overall sleep quality [6]. However, a significant proportion of the population (approximately 20%) experiences sleep deprivation or poor-quality sleep [7,8,9,10]. Sleep problems refer to deficiencies in the quantity and quality of sleep. Issues that affect the continuity of sleep are collectively referred to as sleep disorders.

Sleep disorders are characterized by persistent sleep disturbances and associated daytime dysfunction [11]. Numerous factors can cause sleep disturbances, ranging from lifestyle and environmental factors to sleep disorders and other medical conditions. Sleep disturbances have significant negative short- and long-term health consequences. Poor sleep quality could be a precursor to chronic diseases, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and psychopathology [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Chronic sleep issues and wakefulness disorders adversely affect physical and mental health as well as work, academic, and driving activities [18,19,20,21]. Studies suggest that chronic insomnia is a risk factor for other mental health issues [22, 23].

Sleep problems are common across developmental stages. Numerous studies have shown that children who do not get enough sleep are more likely to develop behavioral problems. Prior research has found that impaired sleep in children is strongly associated with stress, aggression, delinquency, attention problems, and poor concentration [24]. In addition, sleep supports physical and neurobiological development as well as emotional growth; it promotes academic learning, academic performance, and cognitive functioning [25,26,27,28]. Furthermore, many studies have reported that lesser sleep duration and sleep problems are associated with lower academic performance, poor school adjustment, and psychopathology [29,30,31]. Sleep disorders also increase the risk of developing and exacerbating symptoms of obesity, lifestyle-related diseases, and depression. Current research in this area has investigated the relationship between sleep and proper cognitive and psychological functioning. Sleep disturbances have been associated with behavioral and emotional problems in children [32, 33]. Studies examining the association between sleep quality and behavioral problems in children have demonstrated a link between children’s externalizing and internalizing problems and poor sleep quality [34,35,36]. Furthermore, a robust relationship has been noted between sleep problems and increased aggression and behavioral problems among children [37, 38]. However, the relationship between sleep habits and behavioral problems in adolescents is not fully understood.

Late bedtimes and inadequate sleep, that is, short sleep, disrupted sleep patterns, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness, have become increasingly common. Growing evidence confirms that sleep problems among the youth significantly hinder learning, cognition, and memory [39, 40]. Sleep problems adversely affect behavior, social competence achievement, and quality of life, and are more pervasive than educational and health professionals realize. Disruptive sleep habits can lead to excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), which is a symptom associated with sleep disturbances [41]. Daytime sleepiness is closely linked with poor school performance and negative perceptions of quality of life. Adolescent sleep is characterized by delayed sleep timing due to a myriad of biological, psychological, and social changes, and the characteristics of the particular stage of life. This delay in sleep onset impairs adaptation to daily timelines and makes it difficult for teenagers to stay awake. This is especially true in situations where they need to be awake—for example, during school hours. For adolescents, sleep quality is especially important because it is critical for brain development and memory processes [42]. Inadequate sleep is associated with negative outcomes in several areas of health and functioning, including physical and psychosocial health, school performance, and risk avoidance behaviors.

Among adolescents, middle school students are busy with daily classes, as well as club activities and studies. As middle school demands more complex academic tasks, adolescents with chronic sleep deprivation or short sleep duration may have poorer daytime functioning and academic performance [43]. The average sleep duration for middle school students is reported to be 7 h and 40 min in the seventh grade and less than 7 h in the ninth grade. As students advance through the grades, they tend to sleep less. Evidence suggests that sleep needs change over one’s life cycle [44]. When sleep duration at night is less than 7 h, alertness and academic performance are objectively impaired, which can affect normal development and quality of life [45, 46]. In particular, first graders are at a high risk of developing sleep disturbances during their elementary school period. Moreover, behavioral and emotional problems have become a major mental health issue among the youth in recent years, with 10–20% of youth worldwide experiencing mental disorders [47]. Such problems appear at a very young age and increase significantly during adolescence. Studies have indicated that behavioral and emotional problems can lead to mood disorders and self-harm [48]. However, the relationship between sleep habits and behavioral problems among adolescents is not fully understood. Therefore, it is important to clarify the association between healthy sleep habits and behavioral problems among middle school students.

Aspects of measuring sleep habits include not only sleep duration, but also sleep quality and onset time. Sleep quality is generally defined in terms of total sleep time, latency to fall asleep, sleep efficacy, degree of fragmentation, and sleep-disturbing events [49,50,51,52]. Although various sleep measures have been developed, the most widely used is the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [53]. The present study aims to clarify the association between sleep habits and behavioral problems in early adolescence, as this association remains unclear.

Current study

We aimed to understand the relationship between sleep habits and behavioral problems in early adolescence.

Methods

Participants

This study is part of a research project examining the impact of the parenting environment on children’s social development and adaptation. For this project, we recruited five-year old children from 52 kindergartens and 78 preschools in Nagoya, Aichi, a major metropolitan area in Japan, in 2014. Since then, we have conducted periodic surveys with these participants each year.

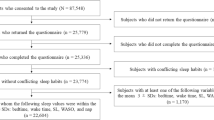

The current study used data from the year 2021. A parent-report questionnaire was administered to a follow-up sample of parents (N = 1288) whose children are currently 12–14 years and in the first grade. The questionnaires were completed by the children’s parents (652 valid responses received). To accurately determine the association between children’s sleep habits and behavioral characteristics, children diagnosed with developmental disabilities and those who did not complete the required items of the questionnaire were excluded from the analysis of this study. As a result, 604 (92.6%) of the 652 children met the eligibility criteria. The mean age of the children was 13.12 years (standard deviation = 0.52, boys: n = 296, girls: n = 308; the mean age was calculated by dividing the age in months by one year).

Ethics statement

At the beginning of the study, the children’s parents were informed about the purpose of the study and associated procedures, and were made aware that participation in the baseline study was voluntary. Parents provided written informed consent on behalf of their children prior to their participation in the study. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Kyoto University Ethics Committee (E2322).

Measures

Explanatory variable: sleep condition

In this study, sleep condition was assessed with the PSQI [53], which is a global measure of sleep quality based on retrospective assessments of sleep behaviors. The PSQI is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 18 items on sleep status during the past month. Through these 18 items, 7 components are calculated: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, sleep medication use, and daytime dysfunction. Each component was rated on a score of 0–3, with a score of 1 or higher indicating being at risk and a score of 0 indicating not being at risk. The sum of these scores was calculated as the global PSQI score, ranging from 0–21. Higher scores indicate more severe sleep problems, including low sleep quality. The PSQI is used to diagnose various sleep disorders and insomnia. The Japanese version was used in this study [54]. It is a highly reliable and valid scale. The sum of the scores for the seven dimensions yields one global score. This global PSQI score has a cutoff of 5 to distinguish between “good sleepers” and “poor sleepers.” A PSQI score of > 5 indicates poor sleep quality and being at risk of sleep problems, whereas a PSQI score ≤ 5 indicates good sleep quality and having a low risk of sleep problems [55].

Objective variable: children’s behaviors

In this study, children’s behaviors were assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [56]. The SDQ is a widely validated instrument for identifying behavioral and emotional problems, as well as prosocial behaviors (25 items). However, in this study, items on prosocial behaviors (5 items) were excluded. The Japanese version, which is a highly reliable and validated tool, was used in this study [57]. The SDQ consists of 20 items assessing behavioral and emotional problems; these items are rated on a three-point Likert scale. Emotional and behavioral problems include emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, and peer problems, which are combined into a total difficulty score by summing the scores of the first four subscales from 0 (low difficulty) to 40 (high difficulty). Higher scores on this scale indicate more emotional and behavioral problems. More specifically, the SDQ total scores are categorized as “normal” (range 0–13), “borderline” (range 14–16), and “abnormal” (range 17–40), indicating the presence of general psychopathology. Therefore, in this study, scores above 17 were considered “abnormal” and scores below 17 were considered “normal.”

Demographic covariates

Parent-reported information was collected on the child’s gender, family structure, household income, and parental education level.

Data analyses

The purpose of this study was to determine the association between sleep habits and behavioral problems. A propensity score method was used to address possible bias due to original sleep habits. In previous studies, sleep problems have been shown to be influenced by child demographics, socioeconomic status, and household characteristics [58]. Therefore, in this study, a propensity score was calculated using gender, family structure, household income, and parental education level as variables that could potentially influence sleep habits. To reduce the effects of bias and potential confounding effects, this study used inverse probability weighting to rigorously adjust for significant differences in participant characteristics. The inverse of the propensity score was incorporated into a weighted logistic regression model to calculate odds ratios (ORs) for behavioral problems due to sleep habits (SDQ total scores). The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27.0.

Results

Table 1 shows the participants’ demographics. The median annual income was ¥5–6 million. University or graduate school was the most common educational background for both mothers and fathers.

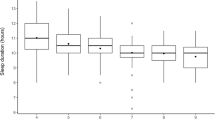

Table 2 shows the participants’ quality of sleep and behavioral problems. The mean sleep duration was 464.31 (52.43) min or 7.74 h.

Tables 3 and 4 shows the association between student attributes and sleep habits. Gender was not associated with sleep habits. In terms of family structure, a higher proportion of children in single-parent households were at risk of a higher PSQI-global score compared to those in two-parent households. In terms of annual household income, children from families with annual incomes of less than ¥3 million were at higher risk of poor subjective sleep quality than those from families with annual incomes of more than ¥3 million. In terms of mothers’ educational background, those whose mothers were less educated (having completed only middle/high school) were more likely to be at risk for poor subjective sleep quality than children whose mothers received higher education (junior college, vocational school, or university/graduate education). Risks of habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, and use of sleeping medication were higher for the former than the latter. Fathers’ educational background showed no association with students’ sleep habits.

Table 5 shows the association between sleep habits and behavioral problems. To examine this association, logistic regression analysis using the inverse weighted method with propensity score matching was conducted, with the explanatory variables being sleep habits (sleep quality, time to fall asleep, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep difficulty, use of sleeping pills, difficulty waking during the day, and sleep disturbances) and the objective variables being behavioral problems (overall difficulty on the SDQ). The results showed that sleep quality (OR) was significantly higher than that of the other variables. Additionally, behavioral problems were significantly higher in the group at risk for poor sleep quality, sleep difficulties, daytime arousal difficulties, and sleep disturbances than in the group with no risk.

Discussion

The mean sleep duration was found to be 464.31 min or 7.74 h. Gender was not associated with sleep habits. A higher proportion of children in single-parent households were at risk of a higher PSQI-global score. Children from families with annual incomes of less than ¥3 million were at higher risk of poor subjective sleep quality. Those whose mothers were less educated (having completed only middle/high school) were more likely to be at risk for poor subjective sleep quality. Fathers’ educational background showed no association with students’ sleep habits. Behavioral problems were found to be significantly higher in the group at risk for poor sleep quality, sleep difficulties, daytime arousal difficulties, and sleep disturbances than in the group with no risk. These results are consistent with those of previous studies, indicating that sleep problems are common in adolescents and can affect behavioral and emotional functioning [24, 59,60,61,62,63].

In this study, the association between daytime sleepiness and behavioral problems was particularly strong. Sleep habits have a direct influence on daytime activity. Poor sleep habits can lead to EDS, one of the main symptoms associated with sleep disturbances. Excessive sleepiness, defined as sleepiness that occurs under conditions in which one would normally expect to be awake, is characterized by EDS, which in turn is caused by a variety of sleep disorders and adversely affects academic performance [64,65,66,67]. Untreated sleep disturbances and associated EDS can lead to behavioral problems, mood disorders, depression, emotional dysregulation, and neurocognitive dysfunction [17, 68,69,70,71]. EDS in children and adolescents is underreported by parents and underdiagnosed by physicians [72]. Prompt detection, diagnosis, and management of EDS are essential.

The average sleep duration for participants in this study was 464.31 (± 52.43) min, or 7 h and 44 min, similar to the average sleep duration in Japan [73]. However, according to the Organisation for Economic Development and Co-operation, Japanese people sleep less than people in the rest of the world [9]. Japan ranks second among countries with the shortest sleep duration (7 h 41 min), compared with France (8 h 48 min), which has the longest sleep duration among developed countries [74]. Adolescents aged 14–17 years need 8–10 h of sleep per day [75]. However, it is well known that children and adolescents get less than the recommended hours of sleep [76, 77]. This pattern of sleep deprivation in children and adolescents is thought to be due to a combination of both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The intrinsic factors include circadian rhythm shifts and sleep-disorder breathing during adolescence [78,79,80]. By contrast, the extrinsic factors, such as earlier school timings, caffeine intake, and exposure to computer games and electronic media, have also been shown to negatively affect sleep duration [81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. Middle school requires more complex academic tasks than elementary school, and adolescents with chronic sleep deprivation or short sleep duration may have poorer daytime functioning and academic performance. Several studies on the neural effects of sleep restriction in early adolescence support the idea that critical prefrontal development at this stage of life has serious behavioral consequences in adulthood [88,89,90]. Thus, the current sleep duration and sleep quality of the youth needs to be increased.

It is important to intervene as early as possible to ensure that persistent sleep problems are not strongly associated with other behavioral problems, such as anxiety, depression, or aggression. Behavioral therapeutic approaches for children with bedtime problems and nighttime awakenings are supported in the literature and should be the first treatment option [91].

Interventions to improve sleep habits are possible. It is strongly recommended that sleep problems be considered in comprehensive assessments, especially for children with psychiatric problems, and that preventive education be part of the usual standard of care. Prior studies have confirmed the effectiveness of behavioral therapy for bedtime problems and frequent nighttime awakening. Evidence has been presented on the efficacy of behavioral therapy in treating people with insomnia [92]. Additionally, behavioral interventions, such as establishing routines and preventive education for parents, have been identified as effective treatments to improve sleep patterns [33, 93,94,95]. Thus, treating insomnia and improving sleep quality may be beneficial for improving children’s learning, aggression, mood, and behavior. In addition and importantly, research is required to assess the impact of interventions on children’s behavior and mood and the use of objective measures in assessing sleep patterns for appropriate interventions [93, 95, 96]. Short sleep duration and frequent nighttime awakenings at 18 months are significant predictors of the development of emotional and behavioral problems five years later [97]. Further, young children who do not sleep well on a regular basis are more likely to experience aggression and attention problems in adolescence [37]. Thus, it may be important to intervene from an earlier age. However, several studies suggest that sleep disorders may be undiagnosed in pediatric clinics [18, 98]. If sleep disorders go undiagnosed, the negative impact on daytime functioning may be significant [64, 98,99,100,101]. Thus, it may be useful to assess and provide timely intervention for adolescents with sleep problems. In particular, regulating sleep quality, sleep difficulties, and daytime arousal difficulties, as indicated in this study, may be effective in reducing the risk of behavioral problems.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. As this was a cross-sectional study, causality could not be determined. Children with more behavioral problems may sleep less and have poorer sleep quality than those who do not show signs of behavioral problems. In addition, the PSQI and SDQ were parent-reported and, thus, vulnerable to reporting bias.

Conclusion

The results suggest that disrupted sleep habits may increase the risk of behavioral problems. Regulating sleep quality, sleep difficulties, and daytime arousal difficulties may reduce the risk of behavioral problems in early adolescence.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the Nagoya child care study but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and are thus not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of the researchers (Rikuya Hosokawa).

Abbreviations

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- SDQ:

-

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- EDS:

-

Excessive daytime sleepiness

References

Shaw PJ, Tononi G, Greenspan RJ, Robinson DF. Stress response genes protect against lethal effects of sleep deprivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2002;417:287–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/417287a.

Consensus Conference Panel, Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, et al. Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Sleep. 2015;38:1161–83. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4950.

Zammit GK, Weiner J, Damato N, Sillup GP, McMillan CA. Quality of life in people with insomnia. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S379–85.

Paunio T, Korhonen T, Hublin C, Partinen M, Kivimäki M, Koskenvuo M, et al. Longitudinal study on poor sleep and life dissatisfaction in a nationwide cohort of twins. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:206–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn305.

Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, Hall WA, Kotagal S, Lloyd RM, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:785–6. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5866.

Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse D, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Sleep. 2015;38:843–4. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4758.

Hublin C, Kaprio J, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M. Insufficient sleep—a population-based study in adults. Sleep. 2001;24:392–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/24.4.392.

Groeger JA, Zijlstra FRH, Dijk D-J. Sleep quantity, sleep difficulties and their perceived consequences in a representative sample of some 2000 British adults. J Sleep Res. 2004;13:359–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869-2004.00418.x.

Soldatos CR, Allaert FA, Ohta T, Dikeos DG. How do individuals sleep around the world? Results from a single-day survey in ten countries. Sleep Med. 2005;6:5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2004.10.006.

Merikanto I, Partonen T. Eveningness increases risks for depressive and anxiety symptoms and hospital treatments mediated by insufficient sleep in a population-based study of 18,039 adults. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:1066–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23189.

Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014;146:1387–94. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0970.

Johnson EO, Roth T, Breslau N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: exploration of the direction of risk. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:700–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.008.

Buysse DJ, Angst J, Gamma A, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rössler W. Prevalence, course, and comorbidity of insomnia and depression in young adults. Sleep. 2008;31:473–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep.31.4.473.

Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E, Stranges S, et al. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep. 2008;31:619–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/31.5.619.

Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:414–20. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1124.

Meng L, Zheng Y, Hui R. The relationship of sleep duration and insomnia to risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Hypertens Res. 2013;36:985–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.70.

Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;9:151–61. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S134864.

Chervin RD, Archbold KH, Panahi P, Pituch KJ. Sleep problems seldom addressed at two general pediatric clinics. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1375–80. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.6.1375.

Owens JA. The practice of pediatric sleep medicine: results of a community survey. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E51. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.3.e51.

Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1254–69.

Drager LF, McEvoy RD, Barbe F, Lorenzi-Filho G, Redline S. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: lessons from recent trials and need for team science. Circulation. 2017;136:1840–50. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029400.

Krystal AD. Sleep and psychiatric disorders: future directions. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29:1115–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2006.09.001.

Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011.

Aronen ET, Paavonen EJ, Fjällberg M, Soininen M. Sleep and psychiatric symptoms in school-age children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:502–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200004000-00020.

Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Sleep and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75:248–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.tb06685.x.

Picchioni D, Reith RM, Nadel JL, Smith CB. Sleep, plasticity and the pathophysiology of neurodevelopmental disorders: the potential roles of protein synthesis and other cellular processes. Brain Sci. 2014;4:150–201. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci4010150.

de Bruin EJ, van Run C, Staaks J, Meijer AM. Effects of sleep manipulation on cognitive functioning of adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;32:45–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.02.006.

Fredriksen K, Rhodes J, Reddy R, Way N. Sleepless in Chicago: tracking the effects of adolescent sleep loss during the middle school years. Child Dev. 2004;75:84–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00655.x.

Dahl RE, Lewin DS. Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(6):175–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00506-2.

Dimitriou D, Le Cornu KF, Milton P. The role of environmental factors on sleep patterns and school performance in adolescents. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1717. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01717.

Williams KE, Nicholson JM, Walker S, Berthelsen D. Early childhood profiles of sleep problems and self-regulation predict later school adjustment. Br J Educ Psychol. 2016;86:331–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12109.

Meltzer LJ. Clinical management of behavioral insomnia of childhood: treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in young children. Behav Sleep Med. 2010;8:172–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2010.487464.

Moore M. Bedtime problems and night wakings: treatment of behavioral insomnia of childhood. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:1195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20731.

Stein MA, Mendelsohn J, Obermeyer WH, Amromin J, Benca R. Sleep and behavior problems in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2001;107: e60. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.4.e60.

Blunden SL, Chervin RD. Sleep, performance and behavior in Australian indigenous and nonindigenous children: an exploratory comparison. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010;46:10–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2009.01610.x.

Byars KC, Yeomans-Maldonado G, Noll JG. Parental functioning and pediatric sleep disturbance: an examination of factors associated with parenting stress in children clinically referred for evaluation of insomnia. Sleep Med. 2011;12:898–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2011.05.002.

Gregory AM, O’Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:964–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200208000-00015.

Hoedlmoser K, Kloesch G, Wiater A, Schabus M. Self-reported sleep patterns, sleep problems, and behavioral problems among school children aged 8–11 years. Somnologie (Berl). 2010;14:23–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-010-0450-4.

Shin C, Kim J, Lee S, Ahn Y, Joo S. Sleep habits, excessive daytime sleepiness and school performance in high school students. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57:451–3. https://doi.org/10.10146/j.1440-1819.2003.01146.x.

Millman RP, Working Group on Sleepiness in Adolescents/Young Adults, AAP Committee on Adolescence. Excessive sleepiness in adolescents and young adults: causes, consequences, and treatment strategies. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1774–86. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0772.

Roehrs T, Carskadon M, Dement W, Roth T. Daytime sleepiness and alertness. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. p. 39–50.

Diekelmann S, Wilhelm I, Born J. The whats and whens of sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13:309–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2008.08.002.

Dewald-Kaufmann JF, Oort FJ, Bögels SM, Meijer AM. Why sleep matters: differences in daytime functioning between adolescents with low and high chronic sleep reduction and short and long sleep durations. J Cogn Behav Psychother. 2013;13:171–82.

Mercer PW, Merritt SL, Cowell JM. Differences in reported sleep need among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:259–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00037-8.

Dahl RE. The impact of inadequate sleep on children’s daytime cognitive function. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996;3:44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1071-9091(96)80028-3.

Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev. 1998;69:875–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06149.x.

Adolescent mental health: fact sheet. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health. Accessed 6 May 2022.

McCann M, Higgins K, Perra O, McLaughlin A. Adolescent ecstasy use and depression: cause and effect, or two outcomes of home environment? Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:845–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku062.

Krystal AD, Edinger JD. Measuring sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S10–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-9457(08)70011-X.

Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM, et al. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:179–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004.

Lovato N, Gradisar M. A meta-analysis and model of the relationship between sleep and depression among adolescents: recommendations for future research and clinical practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:521–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.03.006.

Reynolds KC, Alfano CA. Childhood bedtime problems predict adolescent internalizing symptoms through emotional reactivity. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41:971–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw014.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4.

Doi Y, Minowa M, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Kim K, Shibui K, et al. Psychometric assessment of subjective sleep quality using the Japanese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-J) in psychiatric disordered and control subjects. Psychiatry Res Japn Version. 2000;97:165–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00232-8.

Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:737–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00330-6.

Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x.

Matsuishi T, Nagano M, Araki Y, Tanaka Y, Iwasaki M, Yamashita Y, et al. Scale properties of the Japanese version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): a study of infant and school children in community samples. Brain Dev. 2008;30:410–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.003.

Bonuck K, Freeman K, Chervin RD, Xu L. Sleep-disordered breathing in a population-based cohort: behavioral outcomes at 4 and 7 years. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e857–65. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1402.

Gruber R, Sadeh A, Raviv A. Instability of sleep patterns in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:495–501. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200004000-00019.

Johnson EO, Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Trouble sleeping and anxiety/depression in childhood. Psychiatry Res. 2000;94:93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00145-1.

Scher A, Zukerman S, Epstein R. Persistent night waking and settling difficulties across the first year: early precursors of later behavioural problems? J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2005;23:77–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830512331330929.

Hall WA, Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Parsons DE, Kurinczuk JJ. A model for predicting behavioural sleep problems in a random sample of Australian preschoolers. Infant Child Dev. 2007;16:509–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.527.

Gregory AM, Van der Ende JV, Willis TA, Verhulst FC. Parent-reported sleep problems during development and self-reported anxiety/depression, attention problems, and aggressive behavior later in life. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:330–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.4.330.

Fallone G, Owens JA, Deane J. Sleepiness in children and adolescents: clinical implications. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:287–306. https://doi.org/10.1053/smrv.2001.0192.

Givan DC. The sleepy child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:15–31.

Kothare SV, Kaleyias J. The clinical and laboratory assessment of the sleepy child. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2008;15:61–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2008.03.003.

Mindell JA, Meltzer LJ. Behavioural sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:722–8.

Beebe DW. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(Suppl 3):649–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.002.

Sadeh A, Gruber R, Raviv A. Sleep, neurobehavioral functioning, and behavior problems in school-age children. Child Dev. 2002;73:405–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00414.

Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.005.

Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Bub KL, Gillman MW, Oken E. Prospective study of insufficient sleep and neurobehavioral functioning among school-age children. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:625–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.02.001.

Meltzer LJ, Johnson C, Crosette J, Ramos M, Mindell JA. Prevalence of diagnosed sleep disorders in pediatric primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1410–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2725.

National Health and Nutrition Survey 2018. https://www.nibiohn.go.jp/eiken/kenkounippon21/en/eiyouchousa/. Accessed 6 May 2022.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Society at a glance 2009, OECD social indicators. 2009. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/soc_glance-2008-en.pdf?expires=1653722832&id=id&accname=ocid177290&checksum=ECDD7FFAC88533DB176DC1554F411ED3. Accessed 6 May 2022.

National Sleep Foundation. National Sleep Foundation recommends new sleep times. 2015. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/sleh/NSF_press_release_on_new_sleep_durations_2-2-15.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2022.

Gibson ES, Powles ACP, Thabane L, O’Brien S, Molnar DS, Trajanovic N. “Sleepiness” is serious in adolescence: two surveys of 3235 Canadian students. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-116.

Pagel JF, Forister N, Kwiatkowki C. Adolescent sleep disturbance and school performance: the confounding variable of socioeconomics. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:19–23.

Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Richardson GS, Tate BA, Seifer R. An approach to studying circadian rhythms of adolescent humans. J Biol Rhythms. 1997;12:278–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/074873049701200309.

Ohayon MM, Roberts RE, Zulley J, Smirne S, Priest RG. Prevalence and patterns of problematic sleep among older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1549–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200012000-00019.

Beebe DW, Lewin D, Zeller M, McCabe M, MacLeod K, Daniels SR. Sleep in overweight adolescents: shorter sleep, poorer sleep quality, sleepiness, and sleep-disordered breathing. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:69–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj104.

Wahistrom K. Changing times: findings from the first longitudinal study of later high school start times. NASSP Bull. 2002;86:3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263650208663302.

Higuchi S, Motohashi Y, Liu Y, Ahara M, Kaneko Y. Effects of VDT tasks with a bright display at night on melatonin, core temperature, heart rate, and sleepiness. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2003(94):1773–6. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00616.2002.

Pollak CP, Bright D. Caffeine consumption and weekly sleep patterns in us seventh-, eighth-, and ninth-graders. Pediatrics. 2003;111:42–6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.1.42.

Drapeau C, Hamel-Hébert I, Robillard R, Selmaoui B, Filipini D, Carrier J. Challenging sleep in aging: the effects of 200 mg of caffeine during the evening in young and middle-aged moderate caffeine consumers. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:133–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00518.x.

Dworak M, Schierl T, Bruns T, Strüder HK. Impact of singular excessive computer game and television exposure on sleep patterns and memory performance of school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2007;120:978–85. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-0476.

Calamaro CJ, Mason TBA, Ratcliffe SJ. Adolescents living the 24/7 lifestyle: effects of caffeine and technology on sleep duration and daytime functioning. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e1005–10. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3641.

Peiró-Velert C, Valencia-Peris A, González LM, García-Massó X, Serra-Añó P, Devís-Devís J. Screen media usage, sleep time and academic performance in adolescents: clustering a self-organizing maps analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e99478. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099478.

Lo JC, Lee SM, Teo LM, Lim J, Gooley JJ, Chee MWL. Neurobehavioral impact of successive cycles of sleep restriction with and without naps in adolescents. Sleep. 2017;40:zsw42. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsw042.

Robinson JL, Erath SA, Kana RK, El-Sheikh M. Neurophysiological differences in the adolescent brain following a single night of restricted sleep—a 7T fMRI study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;31:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.03.012.

Lo JC, Twan DC, Karamchedu S, Lee XK, Ong JL, Van Rijn E, et al. Differential effects of split and continuous sleep on neurobehavioral function and glucose tolerance in sleep-restricted adolescents. Sleep. 2019;42:zsz037. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz037.

Thomas JH, Moore M, Mindell JA. Controversies in behavioral treatment of sleep problems in young children. Sleep Med Clin. 2014;9:251–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.02.004.

Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:932–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsu041.

Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, Meltzer LJ, Sadeh A. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29:1263–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/29.11.1380.

Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, Boehlecke B, Brown TM, Coleman J, et al. Practice parameters for behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep. 2006;29:1277–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/29.10.1277.

Tikotzky L, Sadeh A. The role of cognitive-behavioral therapy in behavioral childhood insomnia. Sleep Med. 2010;11:686–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2009.11.017.

Schlarb AA, Velten-Schurian K, Poets CF, Hautzinger M. First effects of a multicomponent treatment for sleep disorders in children. Nat Sci Sleep. 2011;3:1–11. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S15254.

Sivertsen B, Harvey AG, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Torgersen L, Ystrom E, Hysing M, et al. Later emotional and behavioral problems associated with sleep problems in toddlers: a longitudinal study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:575–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0187.

Blunden S, Lushington K, Lorenzen B, Ooi T, Fung F, Kennedy D. Are sleep problems under-recognised in general practice? Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:708–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2003.027011.

Gregory AM, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Poulton R Sleep problems in childhood predict neuropsychological functioning in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1171–6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-0825.

Quach J, Hiscock H, Canterford L, Wake M. Outcomes of child sleep problems over the school-transition period: Australian population longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1287–92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1860.

Langberg JM, Dvorsky MR, Marshall S, Evans SW. Clinical implications of daytime sleepiness for the academic performance of middle school-aged adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Sleep Res. 2013;22:542–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12049.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to all the people who participated in this survey.

Funding

This work was funded by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers 19K19738 and 21H03263.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH acquired the funds needed for the study. RH and TK carried out the investigation. RH was involved in the methodology finalization, project administration, resource acquisition, and securing the software required for the data analysis. TK provided supervision. Validation and visualization were performed by RH and TK. The original draft was written by RH. The draft was reviewed and edited by RT, MF, SA, MS, HT, and KT. All authors have read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, Ethics Committee (E2322). We explained the objectives of the study to the participants and obtained consent from those who agreed to participate. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Parents provided written informed consent on behalf of their children prior to their participation in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosokawa, R., Tomozawa, R., Fujimoto, M. et al. Association between sleep habits and behavioral problems in early adolescence: a descriptive study. BMC Psychol 10, 254 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00958-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00958-7