Abstract

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) as other chronic medical conditions is commonly complicated by depression or other psychiatric symptoms. Results reported in studies present a large variation. Thus, synthetic data are needed to understand impact of depression in adults with SCD. The aim of this literature review is to analyse the methodology used in the studies assessing depression and discuss the different prevalence levels reported.

Methods

Studies involving adults with SCD from 1999 to 2018 were included when providing data on prevalence of depression. It was defined by a psychometric assessment, a structured interview, or a medical record review. PRISMA recommendations were followed.

Results

36 studies are included accordingly to our methodology. Prevalence variation is large, from 0% to more than 85%. We find that the type of assessment tool used plays a major role in this between studies variation. Also, methodological issues arise with respect to psychometric assessment. Moreover, differences emerge between continents, setting of recruitment or time of assessment.

Conclusion

All these issues are discussed to provide insight on depression in adults with sickle cell disease.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO Registration CRD42018100684.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common autosomal recessive disorder in humans [1], in which structurally abnormal haemoglobin leads to severe clinical manifestations such as haemolytic anaemia, greater susceptibility to infections and severe pain attacks [2]. People with SCD (pwSCD) are often affected by depression, and clinical evidence shows a link between emotional state and pathological events, particularly with regard to the major pain crises that remain its hallmark [3]. SCD is thus a major public health issue.

Depression is known to be the most common emotional disorder encountered in chronic diseases [4]. In 2017, the proportion of the world’s population with a depressive disorder was estimated at 3.59%, representing about 264 million people [5].

In international published studies, the prevalence of depressive disorders in medically ill patients is estimated to be between 12 and 61%, depending on the health condition [6]. For example, the worldwide prevalence is estimated between 12 and 40% in diabetes, 14.4% in asthma, 30% to 36% after a heart attack, 20% to 37% in patients with cancer, and 20% to 38% in coronary heart disease [7, 8].

The likelihood of having a comorbid depressive disorder with a chronic disease is significantly higher than having a depressive disorder alone [9]. Having a chronic disease significantly increases the risk of a depressive disorder by an odds ratio of 1.7–3.15 depending on the disease [10, 11].

Likewise, depressive disorders have a negative influence on the progression of chronic diseases. Patients with a chronic disease and a comorbid depressive disorder report significantly more medical symptoms (taking into account the severity of the disease) as compared to patients with chronic pathology alone [12]. In addition, such patients have significantly more hospitalisations for their disease compared to patients without a comorbid depressive disorder [11]. Considering SCD, more specifically, the literature indicates that patients with depression and SCD report increased hospitalizations and intensity of pain experienced as opposed to those with SCD alone [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]; regarding the frequency of pain attacks, studies indicate a higher frequency in patients where depression is also involved [17,18,19, 24, 25]. In particular, with regard to the interference of pain on the daily life of patients, studies show that in sickle cell disease depressed patients tend to feel a greater impact of pain on their lives than healthy patients [24, 26, 27]. These data are consistent with the literature in which the link between depression and pain has been explored (e.g. [28,29,30]).

It would be useful to have similar information in relation to pwSCD. Indeed, as for other chronic diseases, numerous studies have assessed depression in adults with SCD (awSCD), but the range of prevalence varies widely, depending on the assessment tool used: from 0% [31] to more than 85% [32]. The extent of the prevalence range reported emphasises the need for a review of the available data for researchers and clinicians. Accordingly, the aim of this literature review is to analyse the methodology used in the studies assessing depression and discuss the different prevalence levels reported.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We reviewed studies involving awSCD from 1999 to 2018 included. Those involving patients with other psychiatric or medical comorbidities were considered only when the comorbidity was not an explicit inclusion criterion. We did not limit ourselves to patients with a diagnosis of a major depressive episode and considered studies assessing clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Types of outcomes

The evaluation of the prevalence of depression in awSCD was chosen as the primary outcome. It was defined by a psychometric assessment (quantitative data), a structured interview (qualitative data), or a medical record review (qualitative data).

Type of studies

We included research articles and reviews that provided relevant data. In particular, we have endeavoured to identify, in the methodology, the localisation and setting of recruitment, the characteristics of the patients, in particular the percentage of male patient, the average age and the genotype, and also the characteristics of the tools used, including cut-off in the case of psychometric tools.

Other kinds of publications were unsystematically screened to include relevant studies. In this analysis, only studies in English, French and Spanish languages were included.

Search strategy

Eligible studies were identified from PubMed/Medline, ScienceDirect, PsychInfo/Article and a manual search within the references of the articles and reviews found. We only included published articles in peer-reviewed journal.

The search terms used were: “sickle cell” AND depression.

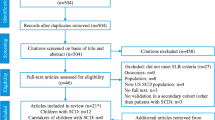

A comparison across the studies, samples and authors was carried out to avoid duplicates and a compilation of data from the same source. Figure 1 shows the steps taken in a flow chart.

Flow chart (from: Moher et al. [34])

Data collection procedure

For this literature review, recommendations from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) were followed [33, 34]:

- Step 1:

-

selection of studies in accordance with our search terms, based on titles and abstract.

- Step 2:

-

in the selected studies at step 1, selection of studies respecting inclusion criteria, based on methodology:

-

only human involved,

-

only adults involved,

-

only sickle cell disease involved,

-

publication date from 1999 to 2018.

-

- Step 3:

-

in the selected studies at step 2, selection of studies with an evaluation of depression providing relevant and exploitable data.

A data extraction sheet based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions’ guidelines (version 5.1.0, updated March 2011) was used [35] and adapted to our specific topic.

The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database: CRD42018100684.

Results

From 1999 to 2018, 36 cross-sectional published studies were found providing data on depression in pwSCD. These data are summarised in Table 1.

Of the 36 studies considered in this review, 30 used a psychometric assessment (PA) tool: of these, 13 used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [36], 4 used the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [37], 6 used the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) [38], 2 used the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [39], Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) [40], 5 used the Longitudinal Exploration of Medical and Psychosocial Factors in SCD (LEMFPSCD), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System and Psychosocial Impact of Sickle Cell Disorder (PROMIS, a self-complete questionnaire designed for the study), and 5 used the Hamilton rating scale [41]. A medical record review (MRR) was used in four studies and two studies used a structured interview (SI) (ED-Scan and Mini).

These 36 studies evaluated a total of 6936 adults. In the total sample, 1665 patients were evaluated with a score above the respective cut-off for indicating depression in each of the assessment tools used, indicating that 24.01% of patients have depression. The sample were 41.10% male with a mean age of 32 years, and 79% had the genotype SS.

Analysis of the methodology used in the included studies

Recruitment setting

Most of the studies (nstudy = 23) used an outpatient population recruited during their normal medical appointment (referred as Outpatient). Some studies used data extracted from a cohort (nstudy = 7). We grouped under the name cohort studies using either a cohort formed in a longitudinal study framework (e.g. PiSCES) or a subgroup selected from a larger group. In these studies, data were extracted at a single time point. Here, the term cohort study is used to distinguish from general outpatient studies (despite the fact that the data is a snapshot at a single time point and hence transversal) because there is a possibility that the monitoring of patients such studies could affect their perception of their illness (referred as Extracted from a cohort). Five studies explicitly recruited inpatients, and one included patients in vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC), which is a severe painful complication requiring treatment during hospitalization [42] (Referred as Inpatient). Finally, in one study, the sample was constituted with both outpatient and inpatient [43].

Of the 30 studies using a PA tool to assess depression, 21 (70%) recruited outpatients and 7 (23.33%) a cohort. Of the 4 MRR studies, 3 (75%) recruited inpatients and outpatients.

Characteristics of the population

The majority of the studies were from the USA (nstudy = 20), nine from Africa or the Middle East, five from South America and two from France.

Despite one study using a large sample [15], the mean sample size is low (npatient = 193). For studies using psychometric assessment tools, npatient = 138; in medical record review, npatient = 627 but decrease to npatient = 211 when excluding the mentioned study; and, in structured interviews, npatient = 150. Of the recruited patient, 41.10% are male (the breakdown among the different assessment methods is as follows: PA: 40.20%, MRR: 42.80%, SI: 50.00%) with a mean age of 32 years old (PA: 32.70, MRR: 25.60, SI: 30.30) and in the mean at 79% with a genotype SS (PA: 80.10%, MRR: 64%, SI: Not provided).

Assessment tool used

The psychometric properties of the instruments used (PA and SI) suggest that these are generally reliably tools, both in their original version (English) and in their adapted versions in other languages. Only one tool was not validated: Psychological Impact of Sickle Cell Disease (PISCD) [44]. The PISCD is a questionnaire designed specifically for use in relation to SCD and has no reported validation. It should also be noted that some articles validating translations of psychometric tools do not report sensitivity and specificity, but provide a measure of internal consistency. This is considered insufficient to guarantee that the psychometric qualities of the original tool are reflected in the translated version. Of course, psychometric tools are screening tools even if they offer discriminating thresholds for levels of intensity of depression.

Specifically, with respect to the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression, of the four studies using it, three use the 20-item version and a cut-off of 16. However, psychometric studies show that this cut-off does not provide the psychometric qualities required to constitute a valid assessment tool because at this cut-off, specificity is only 61.8% [45]. The Wilson–Schaeffer study does report the prevalence of depression for both a CES-D cut-off of 16 (43.4%), but also for the more stringent 27 (18%). For reasons of consistency between the cut-offs used, we will retain in this study the prevalence provided with the cut-off of 16 (43.4%), while being aware of the low specificity of this cut-off. The fourth study, by Laurence et al., uses the 10-item version which has good psychometric properties.

In the MRR, researchers extracted data of interest from medical records. Of the four MRR, three used diagnostic coding to assess the presence of depression. One [46] used reported symptoms related to depression. These methodologies could have biases that could underestimate depression in that depressed patients who have not yet been diagnosed or whose coding is not recorded will not be included in the research (see Table 2).

Depression prevalence reported

The prevalence range of depression is very large, from 0% [31] to 85.90% [32]. All studies combined, the mean prevalence of depression is found to be 24.01%. As the sample sizes have a large range, from 10 to 1874, weighted analysis was used. The mean reported prevalence of each study was weighted according to the total size of the sample considered, in order to take into account the contribution of each study when calculating the general and specific mean prevalences.

Table 3 shows the mean of the prevalence reported using the three different categories of instruments employed in the studies. As can be seen from Table 3, prevalence appears to depend on the type of assessment tool employed. MRR is associated with strikingly lower prevalence (close to 5%) than PA or SI (which are close to 36% and 21% respectively).

Effect of the geographic region

To examine any possible regional influence on the prevalence of depression, we have grouped results according to the location of the studies. The regional regrouping were the USA, South America, Europe, and, Africa-Middle East. Because of the apparent influence of the measurement instrument, only studies that used PA tools were considered (Table 4) when comparing the prevalence in different regions. The results suggest that South America has the lowest prevalence of depression at almost 20%, and that Africa/Middle East has the highest at almost 47%. The USA has an intermediate prevalence at about 34%. The single study from Europe indicated a relatively high prevalence of close to 49%.

Effect of time of measurement on the level of depression measured

We have divided the results into 10-year intervals, again only considering studies employing PA tools (Table 4). Two observations can be made: the number of studies and number of participants increase with time, and the prevalence of depression appears to decrease with time.

Effect of setting of recruitment

We have divided the data according to the setting of recruitment: inpatient and VOC, outpatient, and cohorts (Table 4), considering only studies using PA tools. It appears that the outpatient prevalence is nearly 13 points higher than the cohort prevalence. However, scarcity of data available in the Inpatient group (nstudy = 1) is a limit for further comparison.

Data synthesis: depression in awSCD in the USA

The USA provides by far the largest number of studies included in this review. Of the 20 studies considered, 16 used a psychometric assessment of depression, 3 used a medical record review, and 1 used a structured interview. These studies evaluated 4301 adults with a mean age of 33.21 years. Of these, 39.72% were male (the breakdown among the different assessment methods is as follows: PA: 38.3%, MRR: 42.80%, SI: 52.00%) and 73.91% SS (PA: 75.6%, MRR: 64%, SI: -).

In the USA, the mean prevalence of depression is calculated to be 20.09% (min/max [4.27%; 61%]), using data from all the studies. Differences appear according to the evaluation tool used (PA: 34.33%, MRR: 4.93%, SI: 29.47%) (Table 5). MRR appears to have the smallest mean prevalence level which is consistent with our previous findings. In view of the lack of reliability of the MRRs, they were excluded from analysis according to time and to recruitment setting (Table 5).

In a decade by decade perspective, if we exclude the two studies for the period 1999–2000, the prevalence of depression is stable around 32.00% (99–2000: 41.82%, 2001–10: 32.27%, 11–20: 31.72%).

Depending on the recruitment setting, prevalence appears to be different. In inpatient and VOC groups, prevalence is close to 6%, almost 40% in outpatient group, and 28% in the cohort. This result is equivalent to what we found previously.

The results keeping the regional variable and assessment tool constant are consistent with those previously presented, confirming that MRR tends to provide a lower estimate of the prevalence of depression than PA or SI, questioning us on its use in studies.

Discussion

This literature review has revealed several key points. First, there is a very large difference in the prevalence levels that have been reported, and there are wide differences in prevalence observed across different regions. The mean of all the studies indicates a prevalence of 24%, but the range extends from 0% [31] to more than 85% [32]. The extremities of the range appear to be due to methodological issues. On the one hand, Anim calculates prevalence by dividing the “mean number of individuals in the SCD sample who had indicated non-zero responses” by the total population included [31]. However, prevalence is calculated by dividing the number of cases over the population as the authors specify in their methodology (idem, p. 4). By using an average of the cases, Anim (2016) artificially reduce the reported prevalence. On the other hand, with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Alsubaie (2018) calculate prevalence of depression by assuming that all the score above or equal to 8 indicates a depression regardless of the severity of the depression. However, empirical research has established that this cut-off is too low, and that raised cut-off should be employed [47]. In fact, a cut-off as high as 17 has been proposed [48] to discriminate between depressed and non-depressed patients.

Second, the different measurement tools used in themselves seem to provide very different results. Medical record reviews suggest a prevalence of 5%, whereas psychometric assessment tools tend to indicate a much higher prevalence (36%), as do structured interviews (21%).

In the four articles using a medical record review, two methodologies are used to define the cases. Three articles use diagnostic codes, the last article from Mann-Jiles uses symptoms related to depression. The relatively low prevalence reported with medical record-based assessments is thought to an underestimate due to two methodological biases. First, authors using the diagnostic codes included all the patients with a diagnosis coded between ICD 9 F-296.00 and F-296-89 corresponding, not only to the major depressive disorders, but also to the entire spectrum of bipolar disorders. We would expect to obtain a significant prevalence, which is not the case. These three articles provide the lowest prevalence of depression. One explanation for this low prevalence could be the fact that diagnostic codes of depression are known to be under-reported in administrative records [49]. Then, with regard to the Mann–Jiles article specifically, the authors relied on the presence of certain symptoms relating to depression to label the patient as depressed. However, the authors decided to treat separately some symptoms directly linked to depression such as anhedonia, hyper or hypophagy, insomnia and sleep disorders. This methodological choice, consisting in a particularly restricted definition of depression, may contribute to the weaker recognition of the number of depressed patients, which is not the case. A prevalence close to 20% is found. Overall, there is a contradiction between the methodologies used and the results found. As a consequence, since it is impossible for researchers to estimate the prevalence of underreporting of the diagnosis of depression in medical records, it should be recommended not to use MRRs as a means of estimation of the prevalence of depression.

In respect of psychometric assessment, little attention has been paid to the cross-cultural context in which assessments occurred. A discrepancy can arise between the cultural context in which the assessment tool has been created and the one in which it is used [50]. In that sense, validations of psychometric tools that are only based on translation and internal consistency fail to prove that what they are aimed to measure is really measured. Research has proven that expression of depression varies between culture [51]. In a western context, emotional symptoms are preponderant to somatic symptoms, but this balance might be reversed in other cultures [52]. This issue should be kept in mind when assessing depression in another context than western countries.

Moreover, as with many other chronic conditions, obtaining an accurate diagnosis of depression in sickle cell disease is challenging [53]. Challenges include overlap of neurovegetative symptoms (fatigue and fatiguability, sleep disturbance, and physical pain) found in both depression and sickle cell disease. This challenge is particularly relevant in psychometric assessment completed during hospitalisation when the intensity of symptoms is increased, especially pain and fatigue. Consequently, prevalence of depression found in the five studies that explicitly include inpatients are questionable. Furthermore, due to the episodic nature of depression, a cross-sectional methodology or a single assessment (e.g. 54), can lead to missed cases. It is pointed out that Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [54] avoids neurovegetative symptoms and hence would be particularly suitable for use in with chronically ill patients in a hospital setting.

To take into account any possible geographical effect on prevalence level, we examined more closely studies from the United States (npatient = 20, 56%). Here, we find again that psychometric assessment indicates a slightly higher prevalence (34%) than structured interviews (29%). Given the relatively large number (nstudy = 16) of studies using psychometric assessment, and the total number of participants in these assessments (npatient = 2138), we tentatively suggest that the true extent of prevalence in the USA may be close 34%.

One interesting finding is that the prevalence appears to have decreased globally over the last 20 years when considering studies using only psychometric assessment (Table 4). This may be because the quality of life with the disease has improved or because of the progress in the global management of sickle cell disease and the introduction of new treatments in the last 20 years [55, 56]. However, in the USA this decrease appears to plateau. This is interesting given that since the first introduction of hydroxyurea in 1985 [57] in patients with sickle cell disease, in the United States, and the demonstration of its clinical efficacy in 1995 [58], the quality of care has continued to increase in the United States. Thus, the stagnation of the level of prevalence of depression found in the USA suggests that the improvement of the psychological well-being of the patients cannot be reduced to a therapeutic improvement and that other psychological factors are at play in patients suffering from chronic disease.

From a more general point of view, the socio-demographic or medical characterisation of the samples is incomplete (Table 1). Almost 17% (n = 6) of the studies did not indicate a sex ratio for their overall sample, more than 22% (n = 8) of the studies did not provide clear indications on the age of the patients and 50% ( n = 18) of them do not give the genotypic composition of the patients included. The absence of this information contributes to the poor methodological quality found in the studies.

Conclusion

Studies on the prevalence of depression in pwSCD over a twenty-year period have been examined. The reported prevalence level of depression of pwSCD appears to vary widely depending on the study in question, and in particular on the assessment tool employed. Given that semi-structured interviews are considered the gold standard for diagnostic assessment, it is surprising that only two studies used it, even if cost and time often limit their use. The result of the study using this technique provides a prevalence of 29%, a level that is relatively close to that provided by psychometric assessment (36%) across 30 studies, we tentatively conclude that the true level of prevalence is somewhere between these two figures, rather than the much lower levels of around 5% reported using medical record reviews.

We note that studies across different geographical regions provide different results, but the small number of studies and methodological issues arising in some of these studies precludes us from making drawing any firm conclusions from this. However, an analysis of studies only from the US did not put in question our general findings outlined above. One interesting finding, again only considering studies from the US, was that the prevalence of depression appears to be stagnant with time, which may be due to the improved treatment options for pwSCD and the fact that improving mental well-being cannot be reduced to therapeutic improvement. Clearly, more needs to be done to improve access to treatment, and it is hoped that the analysis of depression in pwSCD reported here will be a useful contribution to understanding how to tackle this issue.

In the future, it would be useful to conduct studies using both structured interviews and psychometric assessment in order to calibrate the psychometric tools employed with pwSCD, and to better understand the discrepancies found between the two techniques. In particular, regarding the limitations of other psychometric tools, the use of HADS is recommended to avoid overlap between symptoms of depression and those of sickle cell disease. It would also be helpful for more studies to be conducted in regions other than the USA and Europe in order to understand the impact of different healthcare systems and cultures on the prevalence of depression with pwSCD.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analysed during this study are included in this published article (Table 1).

Abbreviations

- awSCD:

-

Adults with sickle cell disease

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- BSI:

-

Brief Symptom Inventory

- CES-D:

-

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- DASS:

-

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HAM-D:

-

Hamilton Depression Scale

- ICD-9:

-

International classification of diseases 9th edition

- LEMFPSCD:

-

Longitudinal Exploration of Medical and Psychosocial Factors in SCD

- MRR:

-

Medical record review

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PISCD:

-

Psychological Impact of Sickle Cell Disease

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROMIS:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System and Psychosocial Impact of Sickle Cell Disorder

- pwSCD:

-

People with sickle cell disease

- SCD:

-

Sickle cell disease

- SI:

-

Structured interview

- VOC:

-

Vaso-occlusive crisis

References

Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, Nyangiri OA, Gething PW, Dewi M, et al. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. The Lancet. 2013;381(9861):142–51.

Habibi A, Arlet J-B, Stankovic K, Gellen-Dautremer J, Ribeil J-A, Bartolucci P, et al. Recommandations françaises de prise en charge de la drépanocytose de l’adulte: actualisation 2015. Rev Med Interne. 2015;36(5):S53–84.

Lehougre M-P. La drépanocytose, du risque de mourir au risque de guérir. Enjeux psychique de la greffe de moelle osseuse [Psychanalyse et psychopathologie]. [Paris]: Sorbonne Paris Cité; 2018.

Lotfaliany M, Bowe SJ, Kowal P, Orellana L, Berk M, Mohebbi M. Depression and chronic diseases: Co-occurrence and communality of risk factors. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:461–8.

Global Health Data Exchange. Global Burden of Disease Tool. 2017. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

Steptoe A. Depression and physical illness. Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Clarke D, Currie K. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009;190(7 suppl.):s54-60.

Uphoff EP, Newbould L, Walker I, Ashraf N, Chaturvedi S, Kandasamy A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of common mental disorders in people with non-communicable diseases in Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. J Glob Health. 2019;9(2). https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.020417.

Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Tandon A, Patel V, Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. The Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–8.

Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):409–16.

Patten SB, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH, Modgill G, Jetté N, Eliasziw M. Major depression as a risk factor for chronic disease incidence: longitudinal analyses in a general population cohort. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):407–13.

Katon W, Lin EHB, Kroenke K. The association of depression and anxiety with medical symptom burden in patients with chronic medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):147–55.

Adam SS, Flahiff CM, Kamble S, Telen MJ, Reed SD, De Castro LM. Depression, quality of life, and medical resource utilization in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2017;1(23):1983–92.

Asnani MR, Fraser R, Lewis NA, Reid ME. Depression and loneliness in Jamaicans with sickle cell disease. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(1):40.

Carroll CP, Haywood C, Lanzkron S. Prediction of onset and course of high hospital utilization in sickle cell disease. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(5):248–55.

Carroll P, Haywood C, Hoot M, Lanzkron S. A preliminary study of psychiatric, familial, and medical characteristics of high-utilizing sickle cell disease patients. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(4):317–23.

Grant MM, Gil KM, Floyd MY, Abrams M. Depression and functioning in relation to health care use in sickle cell disease. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22(2):149–57.

Holloway BM, McGill LS, Bediako SM. Depressive symptoms and sickle cell pain: the moderating role of internalized stigma. Stigma and Health. 2017;2(4):271–80.

Morgan KAD, Scott J-K, Parshad-Asnani M, Gibson RC, O’Garo KN, Lowe GA, et al. Associations amongst disease severity, religious coping and depression in a cohort of Jamaicans with sickle-cell disease. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2014;17(9):937–45.

Ola BA, Yates SJ, Dyson SM. Living with sickle cell disease and depression in Lagos, Nigeria: a mixed methods study. Soc Sci Med. 2016;161:27–36.

Raji SO, Lawani AO, James BO. Prevalence and correlates of major depression among Nigerian adults with sickle cell disease. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2016;51(5):456–66.

Wilson Schaeffer JJ, Gil KM, Burchinal M, Kramer KD, Nash KB, Orringer E, et al. Depression, disease severity, and sickle cell disease. J Behav Med. 1999;22(2):115–26.

Jonassaint CR, Jones VL, Leong S, Frierson GM. A systematic review of the association between depression and health care utilization in children and adults with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2016;174(1):136–47.

Levenson JL, McClish DK, Dahman BA, Bovbjerg VE, de Citero AV, Penberthy LT, et al. Depression and anxiety in adults with sickle cell disease: the PiSCES project. Psychosomat Med. 2008;70(2):192–6.

Mahdi N, Al-Ola K, Khalek NA, Almawi WY. Depression, anxiety, and stress comorbidities in sickle cell anemia patients with vaso-occlusive crisis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32(5):345–9.

Dorociak KE, Schulze ET, Piper LE, Molokie RE, Janecek JK. Performance validity testing in a clinical sample of adults with sickle cell disease. Clin Neuropsychol. 2018;32(1):81–97.

Mathur VA, Kiley KB, Haywood C, Bediako SM, Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, et al. Multiple levels of suffering: discrimination in health-care settings is associated with enhanced laboratory pain sensitivity in sickle cell disease. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(12):1076–85.

Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, Peter R, Franke S. Multisite pain, pain frequency and pain severity are associated with depression in older adults: results from the ActiFE Ulm study. Age Ageing. 2014;43(4):510–4.

Stanford EA, Chambers CT, Biesanz JC, Chen E. The frequency, trajectories and predictors of adolescent recurrent pain: a population-based approach. Pain. 2008;138(1):11–21.

Zwart J-A, Dyb G, Hagen K, Ødegård KJ, Dahl AA, Bovim G, et al. Depression and anxiety disorders associated with headache frequency. The Nord–Trøndelag Health Study. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(2):147–52.

Anim MT, Osafo J, Yirdong F. Prevalence of psychological symptoms among adults with sickle cell disease in Korle–Bu Teaching Hospital, Ghana. BMC Psychol. 2016;4(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0162-z.

Alsubaie SS, Almathami MA, Abouelyazid A, Alqahtani MM. Prevalence of depression among adults with sickle cell disease in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. Pak J Med Sci. 2018;34(4):929–33.

Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, et al. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Vol. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100.

Carleton RN, Thibodeau MA, Teale MJN, Welch PG, Abrams MP, Robinson T, et al. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: a review with a theoretical and empirical examination of item content and factor structure. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58067.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605.

Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(1):79–89.

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56–62.

Simo SM, Siela D. Use of a depression and sleep impairment treatment guideline to improve quality of life for patients with sickle cell disease. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2018;24(5):246–55.

Al Sherawi M, Al Alawi M, Al Sinawi H, Al FK. Depressive symptoms among patients in a clinic for sickle cell disease in Oman: a cross-sectional study. Arab J Psychiatry. 2016;27(1):59–66.

Anie KA, Egunjobi FE, Akinyanju OO. Psychosocial impact of sickle cell disorder: perspectives from a Nigerian setting. Glob Health. 2010;6(1):2.

Moon JR, Huh J, Song J, Kang I-S, Park SW, Chang S-A, et al. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale is an adequate screening instrument for depression and anxiety disorder in adults with congential heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):1–7.

Mann-Jiles V, Thompson K, Lester J. Sleep impairment and insomnia in sickle cell disease: a retrospective chart review of clinical and psychological indicators: Sleep impairment and insomnia in sickle cell disease. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;27(8):441–9.

Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K. Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):384–8.

Aben I, Verhey F, Lousberg R, Lodder J, Honig A. Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, SCL-90, and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale as Screening Instruments for Depression in Stroke Patients. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(5):386–93.

Spettell CM, Wall TC, Allison J, Calhoun J, Kobylinski R, Fargason R, et al. Identifying physician-recognized depression from administrative data: consequences for quality measurement. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(4):1081–102.

Marsella AJ. Thoughts on cross-cultural studies on the epidemiology of depression. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1978;2(4):343–57.

Loveys K, Torrez J, Fine A, Moriarty G, Coppersmith G. Cross-cultural differences in language markers of depression online. In: Proceedings of the fifth workshop on computational linguistics and clinical psychology: from keyboard to clinic. Association for Computational Linguistics, New Orleans, LA; 2018. p. 78–87.

Chentsova-Dutton Y, Ryder AG, Miranda J. Understanding depression across cultural contexts. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2014. p. 605. https://culture-emotion-lab.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj9351/f/depressionacrossculturetsaicdryder.pdf.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(10):662–70.

Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):609–19.

Odame I, Jain D. Sickle cell disease: progress made & challenges ahead. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151(6):505.

Salinas Cisneros G, Thein SL. Recent advances in the treatment of sickle cell disease. Front Physiol. 2020;11:435.

Veith R, Galanello R, Papayannopoulou T, Stamatoyannopoulos G. Stimulation of F-cell production in patients with sickle-cell anemia treated with cytarabine or hydroxyurea. N Engl J Med. 1985;19(313):1571–5.

Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1317–22.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DOD: Psychologist, PhD, Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, wrote the first draught. VC: Psychologist, PhD, Reviewing and editing. FB: Methodologist, Pharm D, Reviewing and editing. FG: MD specialist in sickle cell disease, PhD, Professor, Reviewing and editing. MCG: Psychologist, PhD, Professor, Conceptualization, methodology, supervision and reviewing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References included in the review (alphabetical order)

References included in the review (alphabetical order)

-

Adam, S. S., Flahiff, C. M., Kamble, S., Telen, M. J., Reed, S. D., & De Castro, L. M. (2017). Depression, quality of life, and medical resource utilization in sickle cell disease. Blood Advances, 1(23), 1983–1992.

-

Ahmadi, M., Poormansouri, S., Beiranvand, S., & Sedighie, L. (2018). Predictors and Correlates of Fatigue in Sickle Cell Disease Patients. International Journal of Hematology-Oncology and Stem Cell Research, 12(1), 69–76.

-

Al Sherawi, M., Al Alawi, Al Alawi, M., Al Sinawi, H., & Al Farsi, K. (2016). Depressive Symptoms among Patients in a Clinic for Sickle Cell Disease in Oman: A Cross—Sectional Study. The Arab Journal of Psychiatry, 27(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.12816/0023157

-

Alhomoud, M. A., Gosadi, I. M., & Wahbi, H. A. (2018). Depression among Sickle Cell Anemia Patients in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences, 6(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_123_16

-

Alsubaie, S. S., Almathami, M. A., Abouelyazid, A., & Alqahtani, M. M. (2018). Prevalence of depression among adults with sickle cell disease in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 34(4), 929–933. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.344.14760

-

Anie, K. A., Egunjobi, F. E., & Akinyanju, O. O. (2010). Psychosocial impact of sickle cell disorder: Perspectives from a Nigerian setting. Globalization and Health, 6(1), 2.

-

Anim, M. T., Osafo, J., & Yirdong, F. (2016). Prevalence of psychological symptoms among adults with sickle cell disease in Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Ghana. BMC Psychology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0162-z

-

Asnani, M. R., Fraser, R., Lewis, N. A., & Reid, M. E. (2010). Depression and loneliness in Jamaicans with sickle cell disease. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1), 40.

-

Carroll, C. P., Haywood, C., Fagan, P., & Lanzkron, S. (2009). The course and correlates of high hospital utilization in sickle cell disease: Evidence from a large, urban Medicaid managed care organization. American Journal of Hematology, 84(10), 666–670. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.21515

-

Carroll, C. P., Haywood, C., & Lanzkron, S. (2011). Prediction of onset and course of high hospital utilization in sickle cell disease. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 6(5), 248–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.850

-

Dorociak, K. E., Schulze, E. T., Piper, L. E., Molokie, R. E., & Janecek, J. K. (2018). Performance validity testing in a clinical sample of adults with sickle cell disease. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1339830

-

Edwards, C., Green, M., Wellington, C., Muhammad, M., Wood, M., Feliu, M., Edwards, L., Sollers, J. 3rd, Barksdale, C., Robinson, E., McDougald, C., Abrams, M., Whitfield, K., Byrd, G., Hubbard, B., Cola, M., De Castro, L. M., & McNeil, J. (2009). Depression, suicidal ideation, and attempts in black patients with sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Medical Association, 101(11), 1090–1095.

-

Fayand, A., Dzierzynski, N., Georgin-Lavialle, S., Lionnet, F., & Steichen, O. (2016). Influence des comorbidités psychiatriques sur le recours hospitalier pour crise vaso-occlusive chez l’adulte drépanocytaire: Une étude de cohorte. La Revue de Médecine Interne, 37, A67–A68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revmed.2016.10.017

-

Gibson, R. C., Morgan, K. A. D., Abel, W. D., Sewell, C. A., Martin, J. S., Lowe, G. A., Haye, W. D. L., Edwards, C. L., O’Garo, K. N., Reid, M. E., & Asnani, M. R. (2013). Locus of control, depression and quality of life among persons with sickle cell disease in Jamaica. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 18(4), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2012.749353

-

Grant, M. M., Gil, K. M., Floyd, M. Y., & Abrams, M. (2000). Depression and functioning in relation to healthcare use in sickle cell disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 22(2), 149–157.

-

Hasan, S. P., Hashmi, S., Alhassen, M., Lawson, W., & Castro, O. (2003). Depression in sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95(7), 533–537.

-

Jenerette, C., Funk, M., & Murdaugh, C. (2005). Sickle cell disease: A stigmatizing condition that may lead to depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 26(10), 1081–1101. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840500280745

-

Kamble, S., Reed, S. D., Flahiff, C., Adam, S., & DeCastro, L. M. (2010). Resource Use and Expenditures Among Adult Sickle Cell Patients with and without Depression. Blood, 116(21), 1534.

-

Laurence, B., George, D., & Woods, D. (2006). Association between elevated depressive symptoms and clinical disease severity in African-American adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98(3), 365.

-

Levenson, J. L., McClish, D. K., Dahman, B. A., Bovbjerg, V. E., de A. Citero, V., Penberthy, L. T., Aisiku, I. P., Roberts, J. D., Roseff, S. D., & Smith, W. R. (2008). Depression and Anxiety in Adults With Sickle Cell Disease: The PiSCES Project: Psychosomatic Medicine, 70(2), 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815ff5c5

-

Mahdi, N., Al-Ola, K., Khalek, N. A., & Almawi, W. Y. (2010). Depression, anxiety, and stress comorbidities in sickle cell anemia patients with vaso-occlusive crisis. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 32(5), 345–349.

-

Mann-Jiles, V., Thompson, K., & Lester, J. (2015). Sleep impairment and insomnia in sickle cell disease: A retrospective chart review of clinical and psychological indicators: Sleep impairment and insomnia in sickle cell disease. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(8), 441–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12212

-

Mastandréa, É. B., Lucchesi, F., Kitayama, M. M. G., Figueiredo, M. S., & Citero, V. de A. (2015). The relationship between genotype, psychiatric symptoms and quality of life in adult patients with sickle cell disease in São Paulo, Brazil: A cross-sectional study. São Paulo Medical Journal, 133(5), 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2015.00171105

-

Master, S., Arnold, C., Davis, T., Shi, R., & Mansour, R. P. (2016). Anxiety, Depression, Pain Intensity and Interference in Adult Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Blood, 128(22), 1312–1312.

-

Morgan, K. A. D., Scott, J.-K., Parshad-Asnani, M., Gibson, R. C., O’Garo, K. N., Lowe, G. A., Edwards, D., Abel, W. D., Reid, M., De La Haye, W., & Edwards, C. L. (2014). Associations among disease severity, religious coping and depression in a cohort of Jamaicans with sickle-cell disease. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(9), 937–945. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2014.961910

-

Ola, B. A., Yates, S. J., & Dyson, S. M. (2016). Living with sickle cell disease and depression in Lagos, Nigeria: A mixed methods study. Social Science & Medicine, 161, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.029

-

Pells, J., Edwards, C. L., McDougald, C. S., Wood, M., Barksdale, C., Jonassaint, J., Leach-Beale, B., Byrd, G., Mathis, M., & Harrison, M. O. (2007). Fear of movement (kinesiophobia), pain, and psychopathology in patients with sickle cell disease. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 23(8), 707–713.

-

Raji, S. O., Lawani, A. O., & James, B. O. (2016). Prevalence and correlates of major depression among Nigerian adults with sickle cell disease. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 51(5), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217416680839

-

Rosine, M. (2012). Répression émotionnelle, dépression et stratégie de ‘coping’ face à la douleur chez l’adulte souffrant de drépanocytose [Etude observationnelle de 89 sujets]. Université de Lorraine.

-

Simo, S. M., & Siela, D. (2018). Use of a depression and sleep impairment treatment guideline to improve quality of life for patients with sickle cell disease. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 24(5), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2018.24.5.246

-

Treadwell, M. J., Barreda, F., & Kaur, K. (2015). Emotional Distress, Barriers to Care, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 22(1), 10–20.

-

Treadwell, M. J., Barreda, F., Major, K., Walker, V., Payton, W., Kaur, K., & Vichinsky, E. (2011). Mental Health Symptoms, Quality of Life and Barriers to Accessing Health Care in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood, 118(21), 337–337.

-

Vilela, R. Q. B., Cavalcante, J. C., Cavalcante, B. F., Araújo, D. L., Lôbo, M. de M., & Nunes, F. A. T. (2012). Quality of life of individuals with sickle cell disease followed at referral centers in Alagoas, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia, 34(6), 442–446. https://doi.org/10.5581/1516-8484.20120110

-

Wallen, G. R., Minniti, C. P., Krumlauf, M., Eckes, E., Allen, D., Oguhebe, A., Seamon, C., Darbari, D. S., Hildesheim, M., Yang, L., & others. (2014). Sleep disturbance, depression and pain in adults with sickle cell disease. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1), 1.

-

Williams, H., Silva, S., Cline, D., Freiermuth, C., & Tanabe, P. (2018). Social and Behavioral Factors in Sickle Cell Disease: Employment Predicts Decreased Health Care Utilization. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 29(2), 814–829. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2018.0060

-

Wilson Schaeffer, J. J., Gil, K. M., Burchinal, M., Kramer, K. D., Nash, K. B., Orringer, E., & Strayhorn, D. (1999). Depression, disease severity, and sickle cell disease. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 22(2), 115–126.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Oudin Doglioni, D., Chabasseur, V., Barbot, F. et al. Depression in adults with sickle cell disease: a systematic review of the methodological issues in assessing prevalence of depression. BMC Psychol 9, 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00543-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00543-4