Abstract

Background

Postnatal depression (PND) is an important health problem of global relevance for maternal health and impacts on the health and wellbeing of the child over the life-course. Although recent multinational data is hard to locate, the economic burden of PND on health care systems have been calculated in several countries, including Canada and in the UK. In Canada, health and social care costs for a mother with PND were found to be just over twice that of mothers with no mental illness. The extra community care cost for women with PND living in the UK was found to be £35.7 million per year.

Method

We carried out a systematic search to the current literature to investigate the associations between attachment style and PND, using meta-narrative analysis methods, reporting statistical data and core narratives where appropriate. The following databases were searched: PsycInfo, PsycExtra Web of Science, The Cochrane Library and Pubmed. We focused on research papers that examined adult attachment styles and PND, and published between 1991 and 2013. Search terms used were as follows: Attachment, Adult, Maternal, Postnatal, Postpartum, Puerperium and Depression. The final searches in each database took the following form: (Adult OR Maternal] AND Attachment) AND ([Postnatal OR Postpartum OR Puerperium] AND Depress). We included any papers showing relationship between maternal adult attachment and PND. Out of 353 papers, 20 met the study inclusion criteria, representing a total of 2306 participants. Data from these 20 studies was extracted by means of a data extraction table.

Results

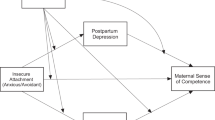

This systematic review is the first to examine and discuss the evidence for an empirical link between postnatal depression and maternal adult attachment style. We found that attachment and PND share a common aetiology and that ‘insecure adult attachment style’ is an additional risk factor for PND. Of the insecure adult attachment styles, anxious styles were found to be associated with PND symptoms more frequently than avoidant or dismissing styles of attachment.

Conclusion

More comprehensive longitudinal research would be crucial to examine possible cause-effect associations between adult attachment style (as an intergenerational construct and risk factor) and PND (as an important maternal mental health), with new screening and interventions being essential for alleviating the suffering and consequences of PND. If more is understood about the risk profile of a new or prospective mother, more can be done to prevent the illness trajectory (PND); as well as making existing screening measures and treatment options more widely available.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Postnatal Depression, PND, (also called Postpartum Depression) is a major depressive disorder or episode with a “Postpartum Onset Specifier” (APA 2000, pp422), sharing the same diagnostic criteria as depression. The ICD-10 classifies it as a “Mild mental and behavioural disorder associated with the peurperium, not elsewhere classified” (WHO 1992, pp357). These different definitions refer PND development from four weeks to one year.

The prevalence of PND in western countries varies from 13% to 19.2% (O’hara and Swain 1996; Joseffson et al. 2001; Huang and Mathers 2001; Gavin et al. 2005). In low and middle-income countries (LMIC), pooled estimates of prevalence rates are reported to be 19.8% (Fisher et al. 2012) and range between 3.5% to 63% (N = 76). The epidemiology of PND is fairly well researched with many empirically supported risk factors giving rise to a complex bio-psychosocial model for its development. Biological risk factors include diet, hormonal changes, childbirth complications and genetic disposition (Starr et al. 2013; Rowe et al. 2013; Bhandari et al. 2012). The strongest psychosocial predictors of depression are depression and/or anxiety in pregnancy, stressful life events, low social support and previous history of mental illness (O’Higgins et al. 2013; Conde et al. 2011; Robertson et al. 2004). Other widely supported psychosocial risk factors include low self-esteem, adjustment problems in the transition to parenthood, vulnerable personality traits (particularly neuroticism), maternal childhood problems (including abuse), low socio-economic status, and relationship discord (NICE 2007; O’hara and Swain 1996; Beck 2001; Robertson et al. 2004).

Attachment theory and postnatal depression

Attachment behaviour can be defined as any behaviour that one elicits with the goal of attracting a defined person deemed better able to deal with the world, to move closer to and to offer care and comfort (Ainsworth 1978; Bowlby 1988). This behavioural system is organised internally in early life reflecting the child’s experience of adapting to his or her caregivers with specific care seeking or soothing behaviours (Ainsworth 1979). In Bowlby’s conceptualisation, all humans are born with this biologically pre-wired disposition that allows us to seek protection when in trouble. The attachment system, one of the main motivational systems organizing child’s development, specifically provides fear regulation mechanisms and thus shapes the child’s ability to regulate her/his emotions. The purpose of the attachment system is indeed promoting and maintaining the secure-base (care giving adult) proximity in order to provide secure intrapsychic processes (normal emotional regulation).

Another key feature of the attachment theory is its inherent relational disposition (bonding). An “attachment bond” (Ainsworth 1989) is a peculiar kind of relational stance, one where the infant looks for a protective relationship with the “older and wiser” adult, i.e. a caregiver. The individual differences in organisation of attachment behaviour (called attachment organisation or attachment style) amongst infants are most often classified as Secure, Insecure (Anxious-Avoidant or Anxious-Resistant) and Disorganised (Ainsworth 1979, 1978; Bowlby 1988). Attachment is “secure” if the child receives protection and security through early developmental stages, and the relationship between the child and his/her caregiver(s) becomes successful throughout life. This implies that the caregiver must provide some basic conditions that are essential for a responsive relationship in order to regulate fear (child’s fear) when attachment system is activated. These basic requirements include emotional availability, sensitivity and empathic attunement; all of which must be maintained through various life phases; or as Bowlby (1983) puts it, from “the cradle to the grave”.

In other words, attachment organisations and styles are found in adults where early childhood experiences set the precedent or draw a road map for later adult attachment behaviours (see Noftir and Shaver 2007; Bartly 2007; Mickelincer and Shaver 2007). Although factor structures arising from different adult attachment studies differ slightly, most adult attachment measures do show a factor analysis that is linked to the theoretical model of Secure, Insecure and Disorganised styles (Mickelincer and Shaver 2007).The main implication of this finding is that people organize their emotion regulation and primary relational modalities in a fairly constant way over the life span due to the development of “internal working models” of relationships (Bowlby 1988). In short, the seminal construct of I.W.Ms. (Internal Working Models) refer to the building up of progressively more mature and sophisticated attachment interactions, mental representations and correlated expectations that allow the child to predict and reflect upon supportive relationships later in life. For example, the more the child experiences secure attachment; the expectations will be more articulated, open, benevolent and positive relational experiences in adulthood. In addition, while the I.W.Ms. affect romantic and other types of relationships, these mental representations also play a major role in parenthood. In the light of the intergenerational transmission constructs (Bowlby 1973), there tends to be a positive correlation between attachment status in the caregiver and the child, especially where the caregiver utilises secure attachment styles.

Moreover, current evidence supports a cross-generational transmission risk of developing depression from mother to child, particularly during the offspring’s childhood and adolescence periods (Katrijn et al. 2012; Bureau et al. 2009); with female trans-generational transmission of PND posing significant challenges to healthcare providers (Sejourne et al. 2011). The links between PND and many different adverse health outcomes for children are strong when depression is chronic and the family has low socioeconomic status (Murray and Cooper 1997; Kurstjens and Wolke 2001; Parsons et al. 2012). Children of depressed mothers have been found to attend fewer health clinics, receive fewer vaccinations and receive more emergency health care interventions than those of mothers with no mental health problems (Minkovitz et al. 2005; Alhusen et al. 2013; Kohlhoff and Barnet 2013). The emotional development of the child is impacted by the mother’s depressive status, which in turn can lead the child to develop cognitive deficits (Beck 1998; Beck 2008) and behavioural problems (Bagner et al. 2010), which also affects the child’s academic achievements (Hay et al. 2001). In some extreme cases, PND outcomes can include suicide and infanticide, though infanticide is less common than suicide among mothers with PND conditions (Spinelli 2004).

This systematic review aims to gain more in-depth understanding of the link between PND and adult attachment styles. Particularly, we aim to systematically analyse and discuss the extent to which the adult attachment style of a new mother can be conceptualised as a risk factor for the development of postnatal depression.

Method

We carried out a systematic search into the current literature using the following databases: PsycInfo, PsycExtra Web of Science, The Cochrane Library and Pubmed. We focused on research papers that examined adult attachment styles and PND, and published between 1991 and 2013. Search terms used were as follows: Attachment, Adult, Maternal, Postnatal, Postpartum, Puerperium and Depression. The final searches in each database took the following form: (Adult OR Maternal] AND Attachment) AND ([Postnatal OR Postpartum OR Puerperium] AND Depress).We included any papers showing relationship between maternal adult attachment and PND.

See Table 1 for more information on inclusion criteria for selecting relevant research papers for the final review. Papers were excluded if they were studying maternal-infant attachment and PND (not maternal adult attachment). We also excluded papers if they did not include both a depression measure and an adult attachment measure or because measures were taken either prenatal or after 12 months postpartum. We assessed the quality of the studies examining the associations between attachment style and PND, adapting the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool, together with the quality assessment Tables we previously compiled (see Deeks et al. 2003; Warfa et al. 2007), making the revised manuscript stronger (see Table 2). No papers received a strong rating for sampling as all samples were conveniently obtained; geographically limited and/or were clinical samples (rather than sampled from general populations).

A strong or moderate rating was given when there was a control group, or the design was longitudinal. A study given strong or moderate rating would have given good validity and reliability values for all measures. A study was assigned weak or strong scores for reporting (or not) direct cause-effect correlations, or moderate rating if an association was made with no specified directions (e.g., cross-sectional). After titles and abstracts were screened from databases such as Pubmed (112), Web of Science (242) and Psycinfo (115), whilst removing non-relevant articles from other sources, 28 articles we carried forward for further examination. 20 Articles met inclusion and criteria, and were selected for the final review. See below for adapted PRISMA flowchart.

Flowchart here

The results are summarised in Table 2; and in the main data extraction Table (Table 3).

Data analysis

The design of this review is a systematic review with narrative synthesis, although reporting on statistical data when it is appropriate (meta-analysis). This method was selected having carried due to the heterogeneity of measurement tools used in the resulting studies and that the research question does not concern efficacy of any treatments for PND. Out of 353 papers, 20 met the study inclusion criteria, representing a total of 2306 participants. Data from these 20 studies was extracted by means of a data extraction table. Tables 2 and 3 summarises the setting of each study and its participants, study design, measures used, aim or hypothesis, quality rating and whether or not a link was found between adult attachment style and PND. The sample represents parents from a range of locations, the majority of these being western countries, but cohorts from Israel (Besser et al. 2002) and Turkey (Akman et al. 2006, 2008; Kuscu et al. 2008; Sabuncuoglu and Berkem 2006) were also found. Six studies carried out hypothesis testing (Besser et al. 2002; Feeney et al. 2003; Kuscu et al. 2008; Meredith and Noller 2003; Pesonen et al. 2004; Simpson et al. 2003), the rest of the studies had no direct hypotheses, only examining associations between PND and adult attachment in the same study or as party of a larger study. Six were cross-sectional (Kuscu et al. 2008; Meredith and Noller 2003; Pesonen et al. 2004; Sabuncuoglu and Berkem 2006; Wilkinson and Mulcahy 2010; Wilkinson and Scherl 2006) and the other 14 were longitudinal with varied follow-up lengths of between 8 weeks (Besser at al 2002) and 12 months postpartum (McMahon et al. 2005).

Results

Every paper in this review found adult attachment style to be significantly linked to PND symptoms, with the exception to Flykt et al. 2010. Seven studies reported an anxious style being significantly linked to PNDS (Bifulco et al. 2004; Feeney et al. 2003; Kuscu et al. 2008; McMahon et al. 2005; Meredith and Noller 2003; Scharfe 2007; Simpson et al. 2003) whereas only three (Monk et al. 2008; Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010) found avoidant styles were more predictive of PNDS. Eight studies found both anxious and avoidant or simply ‘insecure’ styles to be related to maternal PND (Akman 2006; Besser 2002; Conde et al. 2011; Kohlhoff et al. 2013; Pesonen et al. 2004; Sabuncuoglu and Berkem 2006; Alhusen et al. 2013; van Bussel et al. 2005. When comparing studies with regards to the self-report vs. interview conceptualisations of adult attachment, it is difficult to place the Flykt et al. (2010) study into either conceptual school of thought regarding adult attachment because it used the AAI (an interview measure) which had been converted into a questionnaire (self-report). The validity of this measure is not clear and it presents a complication when trying to explain the reason behind the lack of association between the two variables in question. The only other interview measure used across the studies, the Attachment Style Interview, was used by Bifulco et al. (2004) and Conde et al. (2011) and did give rise to a significant association between mother’s insecure attachment and PND. Self-report depression measures were also more frequently used, with only two studies using diagnostic interviewing (Bifulco et al. 2004; McMahon et al. 2005). Table 4 show statistically significant variables that are linked to PND (**) or Attachment style (*).

This Table also shows demographic and other relevant data included in the inferential statistical analyses of the 20 studies. Three variables were found to be linked only to attachment style in three separate studies; social class (Bifulco et al. 2004), marital status (Bifulco et al. 2004), and spouse attachment style (Conde et al. 2011; Feeney et al. 2003; Simpson et al. 2003). Ten variables were associated with PND score alone and each in one study only; infant health problems (Meredith and Noller 2003), gestational diabetes (Besser et al. 2002), parity, planned pregnancy, partner’s happiness regarding the pregnancy (Meredith and Noller 2003), national language proficiency (McMahon et al. 2005) and being the primary caregiver/a housewife (Sabuncuoglu and Berkem 2006). Age of infant, (Flykt et al. 2010; Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010) education level (McMahon et al. 2005; Monk et al. 2008), perceived infant temperament (Feeney et al. 2003; Meredith and Noller 2003), income (Meredith and Noller 2003; Monk et al. 2008), early childhood experience of parents (Meredith and Noller 2003; Alhusen 2013; Van Bussel et al. 2005), cognitive defence/coping style (McMahon et al. 2005; Van Bussel et al. 2005) and history of depression (Meredith and Noller 2003; Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010) were each found to be linked to PND symptoms in two separate studies, increasing the validity of these findings.

Variables found to be correlated to both PND symptoms and attachment style but over separate studies were maternal age (Besser et al. 2002; Monk et al. 2008; and Van Bussel et al. 2005), employment status (Bifulco et al. 2004; Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010), relationship quality/satisfaction (McMahion et al. 2005, Meredith and Noller 2003; Scharfe 2007 and Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010), living with extended family (Bifulco et al. 2004; Kuscu et al. 2008), social support (Akman et al. 2008; Bifulco et al. 2004; Kuscu et al. 2008; Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010), breastfeeding duration (Akman et al. 2008; Wilkinson and Scherl 2006), prenatal depression (Besser et al. 2002; Bifulco et al. 2004; Monk et al. 2008; Van Bussel 2005), maternal anxiety (Akman et al. 2006; Conde et al. 2011; Kuscu et al. 2008; Monk et al. 2008) and maternal neuroticism (Simpson et al. 2003 and Van Bussel et al. 2005).

Risk factors associated with both PND symptoms and attachment style in the same study analysis were maternal anxiety and psychological wellbeing (Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010; Kohlhoff et al. 2013), life adversity/life stress (Monk 2008), infant to mother attachment (Alhusen et al. 2013; Flykt et al. 2010), perceived infant temperament (Pesonen et al. 2004), infantile colic (Akman et al. 2006), experience of pregnancy (Alhusen et al. 2013; Monk et al. 2008), early childhood experience of parents (Alhusen et al. 2013; McMahon et al. 2005), historic parental separation during childhood (Bifulco et al. 2004), social support and relationship quality/satisfaction (Wilkinson and Mulachy 2010) and spousal behaviour/support (Besser et al. 2002 and Simpson et al. 2003).

Discussion

Depression is one of the most widely studied clinical conditions, particularly when it comes to maternal depression and child attachment security. Maternal PND is a clinical condition that not only affects the mother but also the psychological health of the whole family (NICE, 2007). Children of depressed mothers are at higher risk to develop insecure attachments as maternal depression tends to affect the quality and sensitivity of parenting styles. This process has been demonstrated in relation to the more transient form of maternal depression, i.e. PND. Several authors illustrate how the infant bonding process can be threatened by maternal PND, which in turn leads to less secure infant attachment experience and more disorganised (Toth et al. 2001; van IJzendoorn 1999; Martins and Gaffan 2000), as well as avoidant infant attachment styles (Alhusen 2013; Kohlhoff 2013). 19 out of 20 studies included in this review found PND to be statistically associated with insecure adult attachment style. Compared with avoidant or dismissing styles, anxious attachment styles were more frequently associated with PND symptoms, although this may be merely due to the defensive characteristic that avoidant adults tend to exhibit.

The findings of this systematic review show that other risk factors were related to both PND and insecure adult attachment style (see Table 4); hinting at a covariance between these two constructs (See for example, Kohlhoff et al. 2013). In the case of early loss of attachment relationship and/or in consistent secure attachment provision from a primary caregiver, the child is at a higher risk for developing an insecure attachment style later in life, with an associated risk to the onset of a PND condition that predicts depression during childhood and adolescence stages (Duggal et al. 2001). Referring back to the roles played by the Internal Working Models in parenthood, mother’s PND will affect her child’s attachment style through concomitant impairment of sensitive and inadequately attuned care giving practices. In other words, the adverse life events experienced by a mother with PND will have a knock on effect on her child, both through the mother’s clinical conditions and because of not being able to promote and maintain a stable and secure attachment relationship. Recently, the UK Patients’ Association used the Freedom Information Act to obtain information from 150 Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) on NHS service provision for mothers with PND conditions. Their report found that 78% of the PCTs have no information of the incidence of PND in their region; 45% failed to provide information on the number of “Serious Untoward Incidents” related to PND in the services they commission, and 55% of PCTs do not provide information to mothers with PND (The Patients Association, 2011; Pg1). The evidence-based information pulled together in this systematic review will enable practitioners and researchers to have a better understanding of the epidemiology and predictors of postnatal depression, with insecure attachment style and a range of other adverse factors complicating the specific needs of this patient group. Comparatively, a few studies have investigated direct cause-effect links between adult attachment style and PND, again highlighting the importance of acknowledging and addressing PND and its relation to attachment style as an emerging public health priority for the general population (including adult groups); both from research and clinical perspectives.

Methodological considerations

A review of research is only as great as the sum of its parts, even if the outcomes of the studies are pointing towards the same conclusion. One is not able to ascertain whether this data is generalizable as the reliability of the samples implying population level results is restricted. Measurement of depression varied across the studies in different ways. Measurement tools used were not uniform (see data extraction Table) and the type of data used in analysis varied. Only one study analysed depression data as categorical data, depressed or not depressed; the rest of studies featured analysis of depression as continuous or both and categorical, meaning the depression was understood as a common sub-threshold symptom that was relevant even if clinical diagnoses were not made. Cut off scores for depression varied across studies, for example, of the 13 studies using the EPDS (see Table 3), two used continuous data only and four studies used a cut off score of ≥13, three used a cut off score of ≥12, one used a cut off score of ≥11 and one used a cut off score of ≥10. For these reasons, it is important to note that this review uses the term PND (post natal depression symptoms) when making conclusions informed by the data from these 20 studies.

Moreover, there was no data on adult attachment styles and PND in low income countries, and therefore difficult to know if mothers living in low income countries experience PND conditions, induced by insecure adult attachment styles. A key recommendation for future research would be to complete large international longitudinal studies from multiple selection sites, using a mixture of interview and self-report attachment and PND measures in order to redress the imbalance of white, middle class, western, married participants within this research pool. It would be important to measure and model those variables such as self-esteem and family history of mental illness which may also explain some of the shared variance in PND and attachment scores, which is missed by the current literature. The use of tools as screening devices for empirically established risk factors for postnatal depression is helpful in antenatal and mental health care systems. This will allow for tailoring care to the individual formulation of risk and could provide healthcare workers and prospective mothers with knowledge, psycho-education and more resources to intervene if PND should develop.

Conclusions

Although no cause-effect direction has been established yet, one can theoretically deduce the direction of the relationship. Because attachment is a trait which develops in infancy and is fairly stable across the lifespan, insecure adult attachment should be highlighted as a highly important risk factor for PND. Factors linked to adult attachment style include low economic status, being female, experiencing childhood adversity (trust betrayal, abuse and/or loss), parental psychopathology and neuroticism. These variables are also implicated as causing PND. Other risk factors of PND linked to adult attachment style are: lower opinions of partner support (Rholes and Simpson 2001), lower levels of marital relationship functioning (Rholes and Simpson 2001; Carnelly et al. 2004), lower levels of relationship satisfaction (Brennan and Shaver 1995; Shi 2003), and social support (Anders and Tucker 2000). Finally, the development and use of a specific measure that taps on adult attachment and PND measure could prove an effective way to formulate ones’ risk, to help prepare the family for the arrival of the child and for services to funnel resources and time into those families who are more at risk of insecure adult attachment style and PND conditions.

Additional file

References

Ainsworth MDS, Blehar M, Walther E, Wall S: Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. 1978, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey

Ainsworth MDS: Infant-mother attachment. American Psychologist. 1979, 34: 932-7.

Alhusen JL, Hayat MJ, Gross D: A longitudinal study of maternal attachment and infant developmental outcomes. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2013, 16 (6): 521-9.

Akman I, Kuscu K, Ozdemir N, et al: Mothers’ postpartum psychological adjustment and infantile colic. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2006, 91: 417-19.

Akman I, Kuscu MK, Yurdakul Z, Ozdemir N, et al: Breastfeeding duration and postpartum psychological adjustment: role of maternal attachment styles. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2008, 44: 369-73.

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 2000, APA, Washington, DC, 4

Anders SL, Tucker JS: Adult attachment style, interpersonal communication competence and social support. Personal Relationships. 2000, 7: 379-89.

Bagner DM, Pettit JW, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR: Effect of maternal depression on child behavior: a sensitive period?. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010, 49: 699-707.

Bartley, M, Head, J, & Stansfield, S. (2007). Is attachment style a source of resilience against health inequalities at work? Social Science and Medicine, 765–75.

Bartholomew K, Moretti M: The dynamics of measuring attachment. Attachment and Human Development;. 2002, 4: 162-5.

Bashiri N, Spielvogel AM: Postpartum depression: a cross cultural perspective. Primary Care Update for OB/GYNSI. 1999, 6: 82-7.

Besser A, Priel B, Wiznitzer A: Childbearing depressive symptomatology in high-risk pregnancies: the roles of working models and social support. Personal Relationships. 2002, 9: 395-413.

Beck CT: The effects of postpartum depression on child development: A meta-analysis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1998, 12: 12-20.

Beck CT: Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nursing Research. 2001, 50: 275-85.

Belsky J, Jaffee S: The Multiple Determinants of Parenting. Developmental Psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Edited by: Cicchetti D, Cohen D. 2006, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, 38-85. 2

Bifulco A, Figueiredo B, Guedeney N, et al: Maternal attachment style and depression associated with childbirth: preliminary results from a European and US cross-cultural study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004, 184 (Supplement 46): s31-s37.

Bowlby J: Attachment and Loss: Vol. 3 Loss. 1980, Basic Books, New York

Bowlby J: A Secure Base: Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory. 1988, Routledge, Oxfordshire, UK

Brennan KA, Shaver PR: Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995, 21: 267-83.

Bureau JF, Easterbrooks MA, Lyons-Ruth K: Maternal depressive symptoms in infancy: unique contribution to children’s depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence?. Development and Psychopathology. 2009, 21: 519-37.

Carnelley KB, Pietromonaco PR, Jaffe K: Depression, working models of other and relationship functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994, 66: 127-40.

Handbook of Attachment. 2008, The Guilford Press, New York, 2

Conde A, Figueiredo B, Bifulco A: Attachment style and psychological adjustment in couples. Attachment & Human Development. 2011, 13: 271-91.

Duggal S, Carlson EA, Sroufe LA, Egeland B: Symptomatology in childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2001, 13: 143-164.

Eberhard-Gran M, Garthus-Niegel S, Garthus-Niegel K, Eskild A: Postnatal care: a cross-cultural and historical perspective. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2010, 13: 459-66.

Europeean commission Eurostat. Fertility Statistics. 2012. URL: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php/Fertility_statistics. Accessed date 09/11/2012)

Feeney J, Alexander R, Noller P, Hohaus L: Attachment insecurity, depression, and the transition to parenthood. Personal Relationships. 2003, 10: 475-93.

Fisher JRW, Cabral De Mello M, Patel V, et al: Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of theWorld Health Organisation. 2012, 90: 139-49.

Florian V, Mikulincer M, Butcholtz I: Effects of adult attachment style on the perception and search of social support. Journal of Psychology. 1995, 129: 665-76.

Flykt M, Kanninen K, Sinkkonen J, Punamaki RL: Maternal depression and dyadic interaction: the role of maternal attachment style. Infant and Child Development. 2010, 19: 530-50.

Gavin N, Gaynes B, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T: Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005, 106: 1071-83.

Goldbort J: Transcultural analysis of postpartum depression. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2006, 31: 121-6.

Halbreich U, Karkun S: Cross-cultural and social diversity of prevalence of postpartum depression and depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006, 91: 97-111.

Hanlon C, Whitley R, Wondimagegn D, Alem A, Prince M: Postnatal mental distress in relation to the sociocultural practices of childbirth: an exploratory qualitative study from Ethiopia. Social Science and Medicine. 2009, 69: 1211-19.

Hay DF, Asten P, Mills A, Kumar R, Pawlby S, Sharp D: Intellectual problems shown by 11-year-old children whose mothers had postnatal depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001, 42: 871-89.

Huang Y, Mathers N: Postnatal depression – biological or cultural? A comparative study of postnatal women in the UK and Taiwan. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001, 33: 27987-

Josefsson A, Berg G, Nordin C, Sydsjo G: Prevalence of depressive symptoms in late pregnancy and postpartum. Acta Obstetriciaet Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2001, 80: 251-51.

Kirkpatrick LA, Davis KE: Attachment style, gender, and relationship stability: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994, 66: 502-12.

Klanin P, Arthur DG: Postpartum depression in Asian cultures: a literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009, 46: 1355-73.

Kohlhoff J, Barnett B: Parenting self-efficacy: links with maternal depression, infant behaviour and adultattachment. Early Human Development. 2013, 89 (4): 249-56.

Kurstjens S, Wolke D: Effects of maternal depression on cognitive development of children over the First 7 Years of Life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001, 42: 623-36.

Kuscu MK, Akman I, Karabekiroglu A, Yurdakul Z, Orhan L, Ozdemir N, Kman M, Ozek E: Early adverse emotional response to childbirth in turkey: the impact of maternal attachment styles and family support. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008, 29: 33-8.

Martins C, Gaffan EA: Effects of early maternal depression on patterns of infant-mother attachment: a meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000, 41: 737-46.

McMahon C, Barnett B, Kowalenko N, Tennant C: Psychological factors associated with persistent postnatal depression: past and current relationships, defence styles and the mediating role of insecure attachment style. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005, 84: 15-24.

Meredith P, Noller P: Attachment and infant difficultness in postnatal depression. Journal of Family Issues. 2003, 24: 668-86.

Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR: Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997, 73: 1092-1106.

Mikulincer M, Shaver PR: Attachment in Adulthood: Stricture, Dynamics and Change. 2007, The Guildford Press, New York, NY

Minkovitz S, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, et al: Maternal depressive symptoms and Children’s receipt of health care in the first 3 years of life. Journal of Paediatrics. 2005, 115: 306-14.

Monk C, Leight KL, Fang YX: The relationship between women’s attachment style and perinatal mood disturbance: implications for screening and treatment. Archives of Womens Mental Health. 2008, 11: 117-29.

Murray L, Cooper P: Effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1997, 77: 99-101.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) [Various contributors]. (2007). Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: The NICE Guidance on Clinical Management and Service Guidance.url: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG045. Accessed date: 20/01/2011

Noftlr EE, Shaver PR: Attachment dimensions and the big five personality traits: Associations and comparative ability to predict relationship quality. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007, 40: 179-208.

Oates MR, Cox JL, Neema S, et al: Postnatal depression across countries and cultures: a qualitative study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004, 184 (S10-S16): 10-16.

O’Hara MW, Swain AM: Rates and risk of postpartum depression-a meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996, 8: 37-54.

Parsons CE, Young KS, Rochat TJ, Kringelbach ML, Stein A: Postnatal depression and its effects on child development: a review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. British Medical Bulletin. 2012, 101: 57-79.

Patients Association. Postnatal Depression Services: An Investigation into NHS Service Provision. 2011. http://patients-association.com/Portals/0/Public/Files/Research%20Publications/Postnatal%20depression.pdf,

Pesonen AK, Raikkonen K, Strandberg T, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Jarvenpaa AL: Insecure adult attachment style and depressive symptoms: Implications for parental perceptions of infant temperament. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2004, 25: 99-116.

Petrou S, Cooper P, Murray L, Davidson LL: Economic costs of postnatal depression in a high-risk British cohort. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002, 181: 505-12.

Priel B, Shamai D: Attachment style and perceived social support: effects on affect regulation. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995, 19: 235-41.

Ravitz P, Maunder R, Hunter J, et al: Attachment measures: a 25 year review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010, 69: 419-32.

Rholes SW, Simpson JA, Campbell A, Grich J: Adult attachment and the transition to parenthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001, 81: 421-35.

Roberts J, Sword W, Watt S, et al: Costs of postpartum care: examining association from the Ontario mother and infant survey. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2001, 33: 19-34.

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE: Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004, 26: 289-95.

Roisman GI, Holland A, Fortuna K, et al: The adult attachment interview and self-reports of attachment style: an empirical rapprochement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007, 92: 678-97.

Rowe HJ, Wynter KH, Steele A, Fisher JR, Quinlivan JA: The growth of maternal-fetal emotional attachment in pregnant adolescents: a prospective cohort study. Journal PediatrAdolesc Gynecol. 2013, 26 (6): 327-33.

Sabuncuoglu O, Berkem M: Relationship between attachment style and depressive symptoms in postpartum women: Findings from Turkey. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry. 2006, 17: 252-8.

Sejourne N, Alba J, Onorrus M, Goutaudier N, Chabrol H: Intergenerational transmission of postpartum depression. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2011, 29: 115-24.

Scharfe E: Cause or consequence? Exploring causal links between attachment and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007, 26: 1048-64.

Shi L: The association between adult attachment styles and conflict resolution in romantic relationships. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2003, 31: 143-57.

Simpson JA, Rholes WS, Campbell L, Tran S, Wilson CL: Adult attachment, the transition to parenthood, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003, 84: 1172-87.

Spinelli MG: Maternal infanticide associated with mental illness: prevention and the promise of SavedLives. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004, 161: 1548-57.

Starr LR, Hammen C, Brennan PA, Najman JM: Relational security moderates the effect of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) on stress generation and depression among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013, 41 (3): 379-88.

Teissedre F, Chabrol H: Étude de l’EPDS (Échelle postnatale d’Edinburgh) chez 859 mères: dépistage des mères à risque de développer une depression du post-partum. L’Encéphale. 2004, 30: 376-81.

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S: A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2004, 1: 176-184.

Toth SL, Rogosch FA, Sturge-Apple M, Cicchetti D: Maternal depression, children’s attachment security, and representational development: an organizational perspective. Journal of Child Development. 2009, 80: 192-208.

van Bussel JCH, Spitz B, Demyttenaere K: Depressive symptomatology in pregnant and postpartum women. An exploratory study of the role of maternal antenatal orientations. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2005, 12: 155-66.

van Izjendoorn MK: Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness and infant attachment: A meta-analysis on the predictive validity on the adult attachment interview. Psychological Bulletin. 1995, 117: 387-403.

van IJzendoorn MH, Schuengel C, Backermans-Kranenburg MJ: Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Development and Psychopathology. 1999, 11: 225-49.

Wilkinson RB, Mulcahy R: Attachment and interpersonal relationships in postnatal depression. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2010, 28: 252-65.

Wilkinson RB, Scherl FB: Psychological health, maternal attachment and attachment style in breast- and formula-feeding mothers: a preliminary study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2006, 24: 5-19.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the reviewers who made comments on early drafts. We did our best to incorporate their useful and often critical suggestions into the final paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have contributed to the content and editing of the paper. MJH conceived and carried out the study under the supervision of NW. MJH produced the first draft, and worked on consecutive ones. NW collaborated and supervised the study from inception and worked on subsequent drafts, producing the final manuscript. GN helped the design and analysis of the data and worked on consecutive drafts. KB co-supervised and edited consecutive drafts. All authors have read and approved the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Warfa, N., Harper, M., Nicolais, G. et al. Adult attachment style as a risk factor for maternal postnatal depression: a systematic review. BMC Psychol 2, 56 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-014-0056-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-014-0056-x