Abstract

Objective

To synthesise young person and family member perspectives on processes of change in family therapy for anorexia nervosa (AN), including systemic family therapy and manualised family-based treatments, to obtain an understanding of what helps and hinders positive change.

Method

A systematic search of the literature was conducted to identify qualitative studies focussing on experiences of therapeutic change within family therapies for AN from the perspectives of young people and their families. Fifteen studies met inclusion criteria and underwent quality appraisal following which they were synthesised using a meta-synthesis approach.

Results

Six overarching themes were generated: “A holistic focus on the young person’s overall development”; “The therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for change”; “The therapist’s confinement to a script and its impact on emotional attunement”; “A disempowering therapeutic context”; “Externalisation of the eating disorder (ED)”; and “The importance of family involvement”. Positive change was helped by understanding and support given to the young person’s overall development including their psychological, emotional, social and physical wellbeing, positive therapeutic relationships, relational containment within the family system and externalising conversations in which young people felt seen and heard. Positive change was hindered by inflexibility in the treatment approach, counter-effects of externalisation, negative experiences of the therapist, a narrow focus on food-intake and weight, as well as the neglect of family difficulties, emotional experiences, and psychological factors.

Conclusions

Positive change regarding the young person’s eating-related difficulties ensued in the context of positive relational changes between the young person, their family members, the therapist and treatment team, highlighting the significance of secure and trusting relationships. The findings of this review can be utilised by ED services to consider how they may adapt to the needs of young people and their families in order to improve treatment satisfaction, treatment outcomes, and in turn reduce risk for chronicity in AN.

Plain English summary

This review synthesises the views of young people and their family members regarding their perspectives of therapeutic change within family therapies for Anorexia Nervosa (AN), including both manualised eating disorder-focussed family therapy models (family-based treatment; FBT and AN-focussed family therapy; FT-AN), as well as systemic family therapy (SyFT), to understand which aspects of these treatment approaches are helpful versus hindering to recovery from an eating disorder (ED). Parental involvement was crucial in facilitating the restoration of physical health through the process of parents taking temporary responsibility for the young person’s eating behaviours until they can feed themselves again. However, treatment often failed to acknowledge and address the psychological and emotional difficulties that made the young person vulnerable to developing AN, as well as the psychological distress caused by increasing food-intake and weight. A positive therapeutic relationship in which families felt well supported by their therapist was important in providing containment during a time of familial strain and instability, yet there was a need for greater flexibility and individualisation within manualised ED-focussed family therapy approaches, particularly FBT. The findings highlight the importance of eliciting the young person’s voice to enhance their personal agency in treatment and the value of therapeutic space to improve family functioning and enhance family unity. Lastly, they illuminate the need for manualised ED-focussed family therapy models to allow space for the therapist to emotionally attune to young people and families in order to contain their experience of distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Characterised by excessive preoccupation with control over body weight and eating resulting in life-threatening physical effects, Anorexia Nervosa (AN) has significant emotional, social and relational implications for the individual and their family [1,2,3]. Whilst the onset is typically in adolescence, AN can continue into adulthood [4]. The aetiology of AN is complex and multifactorial [5]; research suggests an interaction of genetic risk with other factors including emotion dysregulation, anxiety, perfectionism, cognitive rigidity, and early feeding difficulties [6,7,8,9].

Family therapies for anorexia nervosa

Family therapies are currently the first line treatment for AN in children and adolescents recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [10]. The development of eating disorder (ED) focussed family therapy models have been built on earlier approaches which were informed by Family Systems Theory. Family Systems Theory describes how family dynamics and processes can contribute to the development and, or maintenance of problems within the family system [11]. Since then, models of family therapy for AN have evolved and emphasise that families are a resource, rather than a treatment target [12].

Family therapy for AN was first developed into a manualised treatment named ‘family-based treatment’ (FBT) by Lock and Le Grange [13]. Since then, this manualised form of family therapy has been futher updated by Eisler and colleagues and is named ‘AN-focussed family therapy’ (FT-AN) [14]. These manualised treatment approaches were developed at the Maudsley, hence they may also be referred to as ‘the Maudsley method’. They are the most evaluated and widely used family therapies for adolescent AN.

Although there are subtle differences between FBT and FT-AN, they are conceptually similar and share certain fundamental principles [15]. Firstly, families are seen as holding important resources, which can be enhanced to help the young person recover; and linked closely with this is the understanding that families have not caused the illness. Secondly, they emphasise the importance of supporting parents to have a central role in managing their young person’s eating from the outset of treatment whilst also holding the longer term understanding that this will need to change through the process of recovery which requires the young person to reclaim developmentally appropriate individuation and independence. Both ED-focussed family therapy models externalise the ED from the outset, prioritise an initial focus on the restoration of food-intake and weight restoration, and subsequently shift focus on to adolescent and family developmental life cycle issues in the later stages of treatment.

While FBT and FT-AN are more similar than different, they vary somewhat in the number of phases described, their emphasis on engagement, the use of formulation, the raising of parental anxiety and the inclusion of individual sessions with the young person [16]. The original FBT method is outlined below, and its further development within FT-AN is subsequently described.

Family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa (FBT)

FBT is a manualised outpatient three phase therapy with a behavioural and educative focus. Phase one focuses on refeeding to increase weight orchestrated by parents who are temporarily given responsibility for the individual’s eating and exercise patterns. Phase two focuses on gradually developing the young person’s independence by progressively returning responsibility for eating to the individual. When safe to do so, the focus is taken away from food to problem-solve family and psychosocial issues which interfere with weight restoration. Finally, phase three addresses remaining concerns related to adolescent development, including the re-establishment of healthy boundaries within the family system, and navigating approaching developmental challenges without reverting to ED behaviours. FBT has five key tenets [17]:

-

(1)

The therapist takes an agnostic stance, engaging the family in facilitating early behavioural change to improve the management of eating-related behaviours, rather than exploring or resolving aetiology.

-

(2)

The therapist uses externalising language encouraging the family to conceptualise AN as an “illness” which has “taken over” the young person.

-

(3)

The therapist takes a non-authoritarian therapeutic stance, viewing parents as experts in their family and assuming that giving parents responsibility for weight restoration enables reorganisation of the family to enhance parental effectiveness.

-

(4)

Therapists empower parents to orchestrate recovery. By not providing explicit instructions, parental confidence is built through allowing for struggle and self-reliance.

-

(5)

FBT utilises a pragmatic approach, adopting a firm initial focus on restoring physical health. Comorbid difficulties are not directly addressed in phase one to ensure that weight restoration is the primary focus and because many are assumed to resolve with eating and weight restoration.

Anorexia Nervosa focussed family therapy (FT-AN)

FT-AN specifically emphasises the engagement of all family members from the outset of treatment, including the young person, and the use of formulation to ensure treatment is individually tailored [18, 19]; FT-AN is a phased treatment which includes (1) engagement and development of the therapeutic alliance; (2) helping the family to manage the eating disorder with specific emphasis on reframing parental feeding as care, not control; (3) exploring issues of individual and family development; (4) ending treatment, discussion of future plans and discharge [14]. The early phases of treatment have a strong focus on practically supporting young people and families to manage ED symptoms, gain weight (if required) and build skills around tolerating related distress. The content of sessions in the later phases is individualised to each family. Common themes include returning to independent eating, managing school and peer relationships, tolerating uncertainty, etc. The number and frequency of FT-AN sessions are not pre-determined, rather they are based on family need and clinical presentation.

Systemic family therapy for anorexia nervosa (SyFT)

Systemic Family Therapy (SyFT) is also used in some settings [20]. SyFT is a less defined family therapy which is not delivered with adherence to a phased manual. SyFT does not have defined principles specifically related to the clinical problem (AN) but more so principles to guide the therapist’s thinking and questioning. SyFT focuses on relationships and making meaning of behaviours to promote change, whereas FBT and FT-AN have a more agnostic, behavioural and practical focus on symptom change. Similar to FBT and FT-AN, the SyFT therapist takes a non-blaming, collaborative stance and encourages parental agency and alliance, however they place greater focus on the family system [21]. Difficulties are conceptualised as arising from the interpersonal relationships, dynamics and narratives about a problem within a family system. Adopting a neutral stance, the therapist explores family patterns of beliefs and behaviours, seeking ways to enable the family to draw on their strengths and generate solutions. SyFT aims to enable family members to express and explore difficult thoughts and emotions safely, understand each other’s experiences and views, appreciate each others needs, and work together to make useful changes in their relationsips and lives [22]. Although there is not a specific emphasis on normalisation of eating or weight, the therapist helps the family address these issues when raised.

Research on family therapies for anorexia nervosa

This section reviews qualitative and quantitative research which has focussed on young people and family member experiences of treatments for AN, as well as their mechanisms of change. A meta-synthesis of views about treatment from the perspectives of young people, parents and professionals underlined the central importance of the therapeutic relationship yet the difficulty in forming alliance due to disagreement about treatment targets and mutual distrust [1]. For therapists, the treatment target was normalisation of the young person’s eating and weight. However, young people wanted treatment to target their psychological and social functioning, as well as their family environment; and parents wanted treatment to explore the origins and causes of AN.

Another meta-synthesis focussed on FBT/SyFT found that whilst young people experienced extreme challenge relinquishing control of their eating, they also considered their caregivers’ involvement in this regard as one of the most important aspects of treatment [23]. However, they also appreciated the gradual restoration of autonomy and assistance with difficulties in family relationships. Moreover, whilst externalisation helped to reduce family criticism and increase praise, young people who engaged in FBT would have liked the causes of AN and other difficulties to have been addressed. Lastly, some young people would have liked individual sessions to address issues they did not feel comfortable discussing with family present.

One recent study which aimed to explore processes of change during FT-AN from the perspective of young people has suggested several factors to be key in promoting change: (1) emphasising engagement with all family members from the outset, (2) ensuring life outside the eating disorder is always brought into treatment sessions, (3) supporting the young person to understand their illness from a different perspective and recognise its impact, (4) creating a home and treatment environment in which the illness cannot be avoided and will be addressed [24].

Service-users emphasise that treatments are most helpful when they recognise the emotional impact of weight gain and address psychological as well as physical aspects of AN [1, 23, 25,26,27]. They highlight the perceived unhelpfulness of professionals’ conceptualisation of recovery as a pre-set target weight, rather than considering the individual’s psychological and emotional experiences, as well as their family relationships.

A review on the role of family relationships in adolescent EDs highlighted the need to refer to the adolescent’s family context to improve understanding of AN [28]. Findings from a study exploring the effects of FBT illuminated a possible mechanism of change, termed “relational containment” suggesting the importance of relational processes in recovery from AN [29]. Another study highlighted the process of evolving through treatment, for both the individual and their familial system [30]; this involved the repairing of damage through enabling others to improve their understanding of AN. The importance of attending to attachment-related issues has also been emphasised [31,32,33,34,35,36]; including the intergenerational transmission of attachment styles, emotional communication and coping styles, as well as attitudes towards eating and weight.

Whilst there is good evidence for the effectiveness of manualised ED-focussed family therapies, they do not work for everyone [37,38,39]. Many young people continue to experience ED-related distress following treatment, or families terminate treatment due to difficulties experienced with the approach. Accordingly, studies have attempted to identify factors that help and hinder change. Parental expressed emotion, hostility and criticism are associated with poor outcomes [40, 41], while parental warmth, increases in parental self-efficacy, and decreases in maternal critical communication and emotional over-involvement predict good outcomes [42,43,44,45]. These findings suggest that decreasing unhelpful interactions in families is important in treatment for AN. The importance of the therapeutic relationship has also been underscored, with a meta-analysis indicating that younger patients benefit from an initial focus on the alliance to build engagement [46].

In summary, expressed emotion, the therapeutic alliance, family relationships, support with understanding and managing disordered eating, attunement to the emotional and psychological experience of disordered eating, as well as developing a sense of identity outside of the ED appear to play a significant role in family therapies for AN.

Review aims and rationale

The main limitation of family therapy treatment manuals for AN is the current lack of knowledge regarding their mechanisms of change [14]. Hence, the specific processes of change underpinning family therapies for AN remains unclear [47]. Consequently, there is a need to identify their active ingredients, and to learn who this approach works for and why [48]. This study aims to understand what helps and hinders recovery in family therapies for AN to provide insights into their processes of change. Many qualitative studies which have focussed on patient and family member perspectives of family therapies for AN have been undertaken with both adolescents and young adults [20]. The World Health Organisation’s definition of ‘young people’ covers the age range of 10 to 24 years [49]. Therefore, this review will synthesise research including adolescents and young adults aged 10 to 24 at the time of treatment, referred to henceforth as ‘young people’.

Method

Study design

A meta-synthesis was considered to be the most suitable approach to answer the study’s research question as it allows for the re-interpretation of meaning across a number of qualitative studies [50]. This was important given that a number of existing qualitative studies have explored the experience of treatment for AN from the perspectives of young people and families allowing for existing meta-syntheses regarding the experience of these treatments. However, no meta-syntheses have specifically explored their processes of change from these perspectives. This meta-synthesis aimed to address this gap by synthesising existing qualitative studies which have gathered data on the experience of family therapies from the perspectives of young people and families to form a new interpretation of the research, allowing for the generation of novel explanatory theory of why and how the intervention works or not.

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [51]. The following databases were systematically searched in August 2022: PsycINFO, Medline, and Web of Science. A hand search was also conducted. The search strategy is described in Table 1 and the search results are detailed within Fig. 1. On PsycINFO and Medline, keyword searches for each concept were combined with subject heading searches using the Boolean operator ‘OR’. Web of Science does not have a search by subject heading function, therefore only a keyword search was conducted. This search was conducted again in April 2024 to account new research (see Fig. 2).

Study selection

Studies were screened at the title and abstract screening phase, and subsequently at the full text screening phase. The inclusion criteria were: (a) peer-reviewed studies published 2002 onwards following publication of the FBT manual; (b) studies employing a qualitative or mixed-method design (provided the qualitative results were derived from open-ended questions); (c) studies whose participants included young people and/ or family members who had engaged in FBT or SyFT for AN within outpatient or inpatient ED services. The exclusion criteria were: (a) studies in languages other than English; (b) and studies with mainly quantitative data, or survey data with closed questions.

Quality appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool for qualitative research was used to assess the methodological quality of papers identified [52]. The checklist has 10 criteria; each paper was given a total score out of 10. This review followed the scoring protocol used by existing ED meta-syntheses [25]. The protocol classified studies from A to C, with A denoting studies scoring 8.5 or above and carrying a low likelihood of methodological flaws; B denoting studies scoring 5 to 8, with a moderate likelihood of methodological flaws, and C indicating a score of less than five and a high likelihood of methodological flaws. Six studies scored within category A, nine studies scored within category B, and none of the studies scored within category C. The mean total score was 7.9. Scores were most commonly lost for criteria 6 and 7 (see Table 2).

Data extraction and synthesis

This review utilised the seven-phase guidance provided by Noblit and Hare [63] for conducting a meta-synthesis which was further refined by Walsh and Downe [64]. Studies which met inclusion criteria were read in full and their results and discussion sections were extracted for analysis. Studies were then compared and translated into one another through identifying overlapping concepts (reciprocal translations) and contrasting concepts (refutational translations) across studies. Reciprocal translation was applied when concepts in one study could incorperate those of another due to their shared meaning. Reciprocal translation involved the exploration and exchanging of analogies, metaphors, themes, ideas and concepts that helped to make sense of the relationships between studies with a focus on finding analogies and explantions that best represented the whole. Refutatinal synthesis involved the identification and analysis of contradicting concepts and conclusions across studies. The concepts were subsequently synthesised to create overarching themes and subthemes (third-order concepts) whereby the identified concepts were made sense of to arrive at new interpretations. Finally, the synthesis was expressed through written form revealing more refined meanings, novel and exploratory theories.

Reflexivity

Researcher subjectivity is inevitable within qualitative research and can be used as a valuable research tool [65]. The first author (SC) had professional experience in delivering NICE recommended treatments for adolescent AN, including manualised ED-focussed family therapies. They also had personal experience in receiving individual therapy approaches for adolescent AN, as well as non-ED focussed systemic family therapy. These experiences helped them to understand the data at an experience-near level, which strengthened the interpretative lens through which the data were read, allowing for a deeper level of analysis. However, they also paid attention to ensuring that the analysis and interpretation stayed close to the data within the primary studies by generating themes which honoured participant quotes.

In terms of researcher positionality in relation to the topic, SC reflected on their pre-conceived ideas prior to conducting this review. They acknowledged the importance of an initial focus on the restoration of eating and weight for physical health through eliciting parental management of eating behaviourals, however they also appreciated the intregral role of emotional attunement and containment throughout this process. In addition, they recognised the importance of addressing the emotional and psychological experiences underlying eating behaviours, as well as considering the young person’s family relationship context. Maintaining a reflexive journal and engaging in reflexive supervision enabled them to use their own experiences to extrapolate meanings further, whilst also broadening their perspective on the emerging themes.

Results

Overview of studies

Table 3 presents details of the included studies. Sample sizes ranged from n = 1 to n = 34. Six studies focussed on the experience of FBT/SyFT for AN from the perspectives of young people; four focussed on the perspectives of young people and parents; two focussed on the perspectives of young people, parents and siblings; and four focussed on parents’ perspectives alone. Data were collected from 152 young people (143 females and nine males), 189 parents and 12 siblings.

The patient age range was 11 to 23 at time of treatment, and 12 to 27 at time of data collection. The majority of patients were female (n = 196), 12 were male. Parent gender was discernible in twelve out of thirteen studies: 92 were mothers and 69 were fathers. Ethnicity was rarely reported. The studies were conducted in Hong Kong, China, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, United Kingdom, United States of America, Sweden and Scotland.

Nine studies collected data from participants who engaged in outpatient FBT. One collected data from participants who engaged in family sessions incorperating FBT principles within the inpatient setting. Two collected data from participants who engaged in outpatient SyFT. One collected data from participants who engaged in either outpatient FBT or SyFT and one collected data from participants who engaged in outpatient FT-AN.

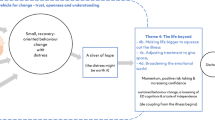

Meta-synthesis findings

Six themes relating to factors that helped and hindered positive change in family therapies for AN were identified (Table 4).

A holistic focus on the young person’s overall development

Families considered it important to maintain a holistic focus in treatment in order to attend to the young person’s overall development including their psychological, emotional and social wellbeing, in addition to their physical health.

The psychological underpinnings of AN

Young people and their parents described pre-existing psychological, emotional and interpersonal difficulties which made individuation and separation from caregivers difficult [53, 59, 61]. Young people conceptualised their eating behaviours as a “coping strategy”; they used restriction as a tool for regulating emotions associated with low self-esteem, difficult life experiences, relationships, separations and transitions [60]. Some parents conveyed concern that externalising AN as “an illness” overlooked a psychological explanation for eating difficulties:

Something causes it […] and not being able to treat what causes it, as well as the anorexia itself, trying to separate the two is a problem. And I come back to the need for a more holistic approach […] something that recognises all the complementary parts and doesn’t try and treat one in isolation of the other [62].

Families reported how AN further impacted on young people’s development as it withdrew them from normal adolescent activities [59, 60]. Young people described feeling “stuck” and unable to relate to their peers who “continued to develop” [53, 59, 60]. Their lives had become small and narrow due to the isolating and all-consuming nature AN [24]. Feeling as though treatment attended to the young person’s emotional, social and psychological development alongside the focus on nourishment enhanced their motivation to endure distress related to making changes to their eating behaviours and weight [24, 59, 60].

Developing a sense of identity beyond the ED

Parents perceived the goals of weight restoration and young peoples’ development as competing and in tension [37, 55, 61, 62]; they considered it crucial to be attentive to balancing these two priorities. The requirement for parents to take responsibility for feeding the young person within phase one led to further developmental regression. Therefore, it was important that later phases of treatment focussed on supporting the development of young people’s autonomy and sense of personal identity beyond the ED [59, 60]. Parents were required to “trust” the process and their young person in order to tolerate anxiety associated with moving away from the structured routines of treatment [60, 61]:

[…] there’s still a part of me that still really worries about it. […], but […] I need to, you know, trust that she is getting better and that she’ll start doing some of the stuff on her own [61].

Young people who experienced more significant difficulties with their identity, anxiety and separation experienced later phases of treatment anxiety-provoking and overwhelming; this was a time of increased risk for returning to disordered eating [24, 59]. Their desire to hold on to the ED was stronger than their desire to return to normal adolescent activities. However, others were motivated to engage in changes to their eating by the prospect of engaging in valued activities and regaining an appropriate level of independence [24, 59, 60]:

As I had more control, I felt like I was more free and more able to enjoy my social life or my schooling life or I was able to work… I was like, well this is great…How could I throw it away and go back to something like that? [59].

Young people conveyed the importance of keeping a focus on their life outside of the ED present in treatment [24]. They emphasised the significance of engaging in meaningful aspects of life and redirecting their focus away from food and weight in order to regain a sense of personal identity beyond the ED. This included reconnecting within relationships, as well as obtaining a sense of mastery and achievement in important areas of life [24, 59, 60]:

It’s been crucial to accomplish high school, to get a driver’s license…It feels really great to accomplish those, it’s this sense of mastering, which is very important. To feel you can live a pretty normal life, where the focus is on everything else but body and food [60].

Addressing the young person in conversations about their health

Some young people spoke about experiencing a moment of clarity or insight in which they realised they were “unwell” and a subsequent realisation that something needed to come from themselves if they wanted to recover [24]. Some young people felt that being spoken to directly with factual psychoeducation within FT-AN regarding the impact of their eating behaviours on their health and functioning from trusted and credible professionals was a factor which contributed to such an awakening [24]:

[…] he was quite harsh about it and really direct, to say that if you keep going this is what could happen. And I think that just scared me a bit but I think I needed that to scare me into recovery to begin with […] [24].

For two young people, a shift in terms of their recovery came from trusting the dietician who joined the treatment process [24, 39]. They were able to utilise the dieticians advice and guidance to challenge their eating behaviors:

[…] when I was faced with a situation to eat a fear food or something, I was like, Okay, remember what the dietitian said. […] And, I guess, for the eating disorder, it was like the biggest thing that was able to go against these thoughts [24].

Hence, addressing the young person in conversations about their overall health and functioning appeared to empower and enhance their sense of personal agency in relation to their eating behaviours.

The therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for change

When the therapeutic relationship was able to hold and contain the young person and family’s distress, it served as a vehicle for positive change.

Young peoples’ experiences of the therapist

On starting treatment, young people described relief coinciding with significant anxiety associated with the prospect of “letting go of control” [24, 56, 60]:

There were two different sides within me, one saying ‘Oh God, this is great, I’m going to get help now’…At the same time, […] ‘No, now they’re going to destroy what you have achieved, and you who have come this far’ [56].

Young people emphasised the time it took for the development of trust in the therapist before they could hand over control or share their feelings [24, 56]. Feeling able to share their internal experiences was perceived as a catalyst for change [24, 56, 57]:

An important part of the turnaround was when I invited her into my feelings. […] I started to trust her [therapist] [56].

Hence, young people conveyed how trust and engagement needed to be prioritised from the outset [24]. They desired human connection, understanding, collaboration, compassion, and non-judgement; a therapist who was factual but who also showed genuine interest in them, rather than solely increasing their food-intake and weight [24, 53, 56, 57, 60]. When the therapeutic relationship had these qualities, young people developed confidence and trust in their therapist:

The key to her significant improvement lies in the fact she trusted her [therapist] completely. It’s so difficult for her to trust anybody [Parent, 60].

Young people described disengagement in the absence of a positive therapeutic relationship. Some conveyed how their disengagement was influenced by a lack of perceived understanding by their therapist, a lack of positive family relationships, or their disagreement with how weight restoration was achieved [56, 59].

Parents’ experiences of the therapist

A positive therapeutic relationship was important in providing parents with emotional containment [29, 57, 62]. Parents desired a clinician who took an active role in aiding parental understanding and support of the young person, as well as family communication [29, 57, 58, 62]:

She [therapist] knew how to teach us to deal with my daughter’s problem and that’s most memorable [57].

The therapist was experienced positively when they had a neutral quality and were compassionate, collaborative, helpful, flexible and placed emphasis on building trust [29, 37, 39, 57, 58, 62]. Parents wanted to feel connected with their therapist, have their concerns contextualised and validated, and their circumstances and values respected [29, 37, 39, 57, 58, 62]:

We have built up mutual trust. There’s genuine concern between her [therapist] and us. She didn’t treat us as if it were her job or profession [57].

Moreover, parents wanted to improve their knowledge of AN in order to feel confident in their capacities to help [58, 61]. A lack of adequate information and guidance given by the therapist contributed to a lack of containment experienced within the therapeutic relationship in FBT [58]:

[…] It seemed to be pushing all the onus on correction and enforcement on to my wife and I, and nothing coming from the clinicians, no support for us in our battle. [58].

Some parents perceived the therapist as cold, harsh, scrutinising, condescending and detached in FBT [29, 37, 39, 57, 58, 62]. One parent made a distinction between a positive experience of SyFT versus a negative experience of FBT, describing the SyFT therapist as coming “alongside” the family, as opposed to the FBT therapist acting as a “removed expert” [62].

The therapist’s confinement to a “script” and its impact on emotional attunement

Families conveyed how positive change was hindered by a confined focus on food intake and weight in FBT.

Neglect of young people’s emotional distress

Young people frequently described FBT as an isolating process that ignored “what was going on inside” wherein their parents and therapist did not understand how distressing increasing their eating and weight was [37, 38, 54, 59]:

[…] they just solely focused on my physical health, they didn’t really take on much consideration as to my mental health and how much of a toll everything was taking on me [37].

Young people desired support with managing the psychological experience of AN and its associated difficulties rather than solely focussing on increasing their food-intake and weight in FBT [57]. Areas of importance included motivation, emotions, thoughts, relationship difficulties, self-esteem, body image and identity issues [37, 38, 54, 58,59,60]:

Because they never really addressed the underlying problems, it was all so much harder than it probably should have been, because I was still battling with the thoughts and the guilt [56].

Some young people felt that important conversations (i.e., the impact of their parent’s attitudes to eating and weight) were not sufficiently acknowledged in FBT [38]:

We opened old wounds and then they never really got closed I never got to just express how I was really feeling, which is probably why I was so angry, because it was all, like building up inside [38].

Some parents emphasised how FBT assumes that weight restoration leads to cognitive change [37, 38]; they expressed concerns that the psychological underpinnings of AN and its associated difficulties were unaddressed by the “FBT script” [37,38,39, 54, 55, 59,60,61]:

The focus seems to be all on the food aspects […] the food is the end product of the whole problem, what’s going on underneath? [39].

When young people were not restoring weight in FBT, parents were concerned by the continued confined focus on food intake and weight as the young person became increasingly distressed and conflicts worsened [39]. They questioned whether FBT was doing more harm than good; for some, this led to treatment termination [37, 38, 56]. For those who engaged in FT-AN, some young people felt that the early stages of treatment were very parent focussed which inhibited their ability to share their internal experiences and resulted in them struggling to engage due to the experience of distress. However, some young people felt that the middle and later phases of FT-AN did attend to their psychological and emotional needs which had a positive impact on their recovery [24]:

[…] early treatment was very much nutrition focused. It was kind of let’s just get her fed enough. And then middle treatment was kind of unpacking lots of fears. […] just things like thoughts around food […]. And then end of treatment for me was kind of looking at what might have caused it, how you can prevent it [24].

Neglect of family distress

Parents often described how being redirected to the “FBT script” caused distancing in the therapeutic relationship and reduced confidence about therapy [29, 37, 58, 62]. Many families conveyed a lack of space for the exploration of familial distress and conflict, which for some contributed to family estrangement and exacerbation of distress in FBT [37, 62]:

FBT ruined a previously strong relationship and caused my parents and siblings their own psychological unease and detriment. This contributed to a loss of myself and my identity and resulted in further destructive behaviours [Young person, 37].

Parents conveyed how the task of “refeeding” as the solution obscured how demanding, distressing and dilemmatic their experience was in FBT. They considered it important to feel resourced emotionally, practically and personally to create capacity for the task of weight restoration; parental management of emotion was significant in this respect [61]. They felt overwhelmed, exhausted, isolated and let down by the therapist when their challenges were not recognised or supported in FBT [29, 37, 39, 58]:

[…] it sounds easy in principle, […] when you actually do it at home it’s not that easy when a teenager’s screaming at the top of her lungs […] you feel a little thrown to the wolves […] once you close the door of your family home that’s it; you’re on your own [62].

Parents engaged in an internal search for answers regarding the cause for their young person’s eating difficulties to provide them with a sense of coherence and to guide day-to-day decision making in FBT [39, 58, 61]. Parents acknowledged the therapists’ attempts to relieve them of guilt and blame with FBT’s agnostic aetiological stance, however described the experience of persistent guilt, self-blame and inadequacy [29, 54, 58, 62]:

[…] it felt like, well as a parent, what have we done wrong? [39].

Parental co-regulation was a strategy for the management of difficult emotions [37, 61], as were internal processes such as practicing acceptance, managing expectations and finding meaning in adversity [61]. However, practical challenges to parents’ capacity such as the lack of time and financial resources posed significant dilemmas for single parents engaged in FBT [61, 62]:

I can’t take any time off work, I don’t have any money, I don’t know how I’m going to help her! [61].

A disempowering therapeutic context

Families conveyed how the experience of disempowerment in treatment was hindering to positive change.

Parents “on trial” in the absence of change

It was important to parents that treatment monitored progress in the overall health and wellbeing of their young person [61]. Attending to markers of progress was a powerful motivator that instilled hope, or revealed what was not working [61]. However, some parents described FBT as a “ruthless”, “dogmatic” approach in which they felt “put on trial” [37, 39]. These parents reported to receive blaming, punitive responses from the therapist when there was insufficient weight restoration in FBT. Such interactions exacerbated parental guilt and self-blame, causing parents to feel exposed and vulnerable [37, 39]:

I have never been so challenged in my life as a mother. I felt wretched. It’s such a fundamental thing to feed and protect your child and anorexia has already challenged that […] then to, on a weekly basis, be in a context (emotional tone to voice) where your failings are on show and also on show to your children [39].

Parents reported that these interactions implicitly conveyed how they were failing in their role as parents and at FBT [37, 39], particularly when the therapist endorsed the assumption that “the Maudsley works”:

I felt like she was on trial […]. Hayley’s failure to put on weight was Margaret’s failure to feed her enough ultimately [39].

Rigid inflexibility versus individualised tailoring of treatment

Some families reported to feel that FBT was “rigid”, “prescribed” and “inflexible” [37, 39]. Families who engaged in FBT or FT-AN would have liked more separated sessions in addition to conjoint sessions throughout treatment in order that parents’ and young peoples’ individual emotional needs could be met [24, 37, 54, 61]:

[…] there were other times where it was just really awkward talking about my deepest, darkest anorexia secrets, I definitely was able to open up more when it was just one on one with my psychologist, about actual behaviours, because you don’t want to admit those kind of things to your parents [Young person, 46].

Families who engaged in FBT reported a lack of tailoring to preferences regarding session format and content, treatment duration, ending, and opportunity to have a follow up [37, 54, 58]:

The rigidity and inflexibility [,,,] was such a shame […] because […] the heavy lifting was done, which was the trust […]. The lack of progress or our frustration or anything to just flex the approach and to lean on the trust that had been built. Well, I think we’d have gone to the edge of the earth with her you know until it became so rigid, dogmatic […] [Parent, 36].

Some families reported that time-limited FBT was not sufficient to support a full recovery [39, 54, 56]. Young people wanted the therapist to be attuned to their needs and to make a collaborative decision rather than ending treatment on reaching a “target weight” in FBT [56]. The therapists’ perceived assumption that they were psychologically recovered on reaching a healthy weight evoked feelings of anger and abandonment:

OK, now you have reached normal weight - so now you are well again. The simple fact that I had put on weight meant that everything was fine, and that was all there was to it. I felt like…I’m not prepared to walk out weighing like this, if you leave me, I will start losing weight again [56].

Externalisation of the eating disorder

Externalisation could help and hinder positive change depending on how it was used and its effects on the young person and their relationships.

Loss of the young person’s voice and identity

Some parents described how young people were spoken about rather than with as a result of externalisation, which contributed to a perceived loss of the young person’s voice and identity in FBT [37, 38]:

[…] I accept that when she was very sick, […] we talk in these beautiful terms of ‘It was the eating disorder and not Hayley in the room’ […] but effectively Hayley was still in the room but she was treated as though she wasn’t [37].

Some young people who engaged in FBT did not find it helpful for others to perceive of them as being under the influence of an external entity because they felt unseen and unheard [37, 38]. Moreover, externalising conversations that highlighted family member burden due to AN were particularly difficult for some as they evoked guilt and shame. Instead, young people wanted their voice to be actively sought and to be given ownership over session content, rather than feel “talked about” and instructed what to do in an impersonalised manner in FBT [37, 56]:

[…] the fact that you had an eating disorder meant they were dismissive of anything you say, they believed anything you say was completely motivated by the eating disorder […]. I was very distressed by that because I thought I’m still me, I’m still here, I can recognise that I have anxiety and unhelpful thoughts but I can still communicate as a person [38].

In contrast, a collaborative involvement in treatment fostered greater security and safety in the young person’s relationships with their therapist and family [24, 37, 53, 56, 60]. Feeling seen as a person beyond the ED helped to build young people’s sense of self, rather than reinforce an illness identity through the exclusion of their voice.

Separation of the problem from the young person

At the start of treatment, conceptualising AN as an ‘unwanted temporary illness’ enabled parents to channel difficult emotions into “fighting” AN [37,38,39, 54].

There was Sally and there was the eating disorder and once you separate them you realise that she is still there and we’re fighting the eating disorder and she is too. […] it wasn’t just her doing this to herself [39].

Some young people conveyed how important it was for their family to realise that EDs are illnesses rather than ‘difficult behaviour’ [24]. The illness metaphor enabled some young people to feel seen and understood “as a person” by their therapist and family [24]. Feeling related to as a person experiencing an illness was validating and containing, rather than dismissive and invalidating:

My [therapist] was really good at explaining to my parents and my family: ‘Actually this isn’t a choice. You know, this isn’t something [young person’s name] woke up one day and decide to do to herself, this is an illness. I’m going to treat it like an illness [24].

However, it was important that externalising conversations validated the young person’s lived experience. For instance, Venn diagrams acknowledging overlaps between the identity of the young person and that of AN, as well as engaging in chair work to speak to AN were described as meeting young peoples’ emotional and psychological needs [38]:

[…] they’d be like, what would your eating disorder say to this? Now sit in this chair and it’d be like, what would you say to this? […] that was helpful, but they just didn’t do it enough. Like, it was just so much about food but they needed to care about my feelings [38].

Young people emphasised the significance of transitioning from “denial” to “realisation” through externalising conversations which elicited the young person’s voice and facilitated reflection on their personal values and life aspirations [37, 60].

Ask yourself, why, why do you do this? What do you want to get out of your life? What are your true dreams? What is your greatest wish? [60].

Young people acknowledged the importance, yet difficulty, of becoming aware of AN’s negative effects and its function in their lives [24, 60]:

It’s important to realize and see more clearly the negative influences the ED has, because it is, after all, a way of handling difficulties or mastering life. […] It’s not easy to be attentive to the negative consequences the ED will have [60].

Young people stressed their anxieties and resistance to making changes to their eating. However, they tolerated difficult feelings in the service of their commitment to a preferred identity underpinned by their personal values [24, 60]:

I haven’t thought much about having kids. Still, I think it is important to stay in treatment, because I want to be able to take good care of my kids, which is a huge motivation for me [60].

The importance of family involvement

Interventions aimed at improving parental understanding and management of AN, as well as family functioning were supportive of positive change.

Improving parental understanding and management of AN

Parents entered treatment feeling powerless, not knowing how to help their young person [62]. For some, the structure and guidance on commencing FBT provided direction which instilled hope [29, 37, 39, 56, 61, 62]:

I felt totally out of control. […] So, having a plan just made me feel like I had something secure to-to work on, to work with, to trust in [39].

One mother conveyed how FBT gave her permission and resources to challenge their young person’s eating behaviour:

Treatment gave me tools and framework and a structure and permission I suppose [29].

Some young people experienced relief, safety and security when control over their eating was taken away in FBT/FT-AN [24, 29, 37, 38]. Most young people acknowledged that they would not have restored weight without parental support with challenging the ED in the process of adhering to their eating plan [24, 29, 37, 38, 60]:

[…] I don’t think I would have been able to gain that weight and get to the medically stable point if it had sort of been all up to me. […] I still definitely needed my family support because […] even if it was unintentionally, I would’ve just slipped back […] [37].

Young people conveyed the perceived helpfulness of psychoeducation and guidance from the therapist and treatment team which enabled their parents to understand and respond to their experiences more effectively [24, 29, 37, 38, 60]. Hence, promoting change at a systemic level was integral to their recovery:

[…] as much as it was about teaching me the correct thoughts, and the correct patterns, […] how to get better. It was also teaching my parents what the right things were to say and what the right behaviours were, and what actually they had done that was maybe not so healthy [24].

A consistent, firm approach to managing eating behaviours was containing to young people in the sense that the parental boundary allowed no escape route for the ED [24]. Parents reflected on the potential of AN to undermine the marital relationship and the importance of parental unification and partnership which involved co-parent coordination and negotiation [39, 58, 60,61,62]. Thus, it was helpful when treatment scaffolded the sharing of roles and responsibilities between co-parents to ease parental burden as well as to ensure that both parents were engaged in changes conducive to young peoples’ recovery [61, 62]:

We were a joint force. I think if you can work together really quickly it helps because an eating disorder can get around one of you, but if it knows that dad’s there backing up everything that mum says and vice-versa […] [39].

Parents who were not supported in treatment by their co-parent would have liked to have shared parental responsibility and were concerned about their co-parent’s lack of understanding for their young person’s difficulties [61, 62]. In the context of parental separation, it was important that both parents pulled together to preserve the young person’s sense of unified family support [62]. This necessitated parental acceptance of disparate parenting philosophies and weight-restoration strategies [62]:

At first it was like, […] “Hello? Uh, that’s not happening”. And then, you know, it’s like, “Actually, we need to do this for [our daughter]. Darn. Okay”. So suck it up, bury those emotions [62].

Strengthening of the parent-young person relationship

Whilst some parents felt that treatment disrupted the parent-young person relationship in FBT [37, 38], others felt it helped them to maintain a connection with their young person. Some parents described personal changes which served to strengthen the parent-young person relationship, for instance becoming firmer with boundaries, more resilient and emotionally attuned [29, 39, 58, 61, 62]:

I was one of these people who didn’t show my emotions much, very tough orientated, very much the job at hand…once I understood what anorexia was like for my son, it helped me change. Now I’ve let my guard down and let people in. […] It’s [AN] made me a better person and a better parent… [62].

Young people acknowledged how difficult it was for their parents to understand AN, however their efforts to do so made them feel worthy of care [24, 38, 56, 61, 62]. In the context of relationships in which young people felt seen, heard, understood and cared for, they were more accepting of the structures put in place to support them with eating [24, 29, 37, 38, 56, 60]. Thus, young people found it helpful when the therapist mobilised emotionally containing relationships [24, 38, 56, 59]. They conveyed the importance of parental support in helping them to cope with ED-related cognitions and emotions which felt too overwhelming and distressing for them to deal with on their own [24]:

[…] there’s a point where the eating disorder’s voice is stronger than anything else in you. And so you are not physically able to fight that yourself. You need help. You need other people to, like, to help fight that voice until you’re capable of doing that yourself [24].

Parental capacity to take non-coercive control over the young person’s eating appeared to be influenced by parents’ capacity to tolerate the young person’s distress [29]. When treatment contained parental anxiety and increased parental confidence, parents had greater capacity to provide emotional containment to the young person [24, 29, 61]. Consequently, over time young people experienced greater security, safety and trust in the parent-young person relationship and were able to replace control with trust in others [24, 29, 37, 56, 59, 61]:

I felt the need to be in control but […] I sort of had to put my trust in to them that they were going to take care of me [29].

Increased relational security in the parent-young person relationship was depicted by young people as learning to understand each other, reduced parental criticism, and increased parental provision of emotional support and reassurance [24, 29].

They tried to be as understanding as they could be [parents] […] it helped because for the first time I didn’t actually shun them, I went to them…it’s so weird cause for the first time in my life I let myself depend on someone else [29].

Parents perceived the quality of connection between themselves and their young person as a tangible marker of positive progress in treatment [29, 61]. These relational changes had a positive impact on young peoples’ attachment system and sense of selves. Young people described reduced self-criticism, improved confidence, greater self-acceptance, increased capacity to trust others and in turn, in their selves [29, 61]. Parents described reduced secretiveness, increased resilience and emotional expressiveness in their young person [29, 61].

Changes to family functioning

Many families entered treatment with strained family relationships. Some young people felt they were a “burden” and “a stranger” within their family [29]:

We weren’t being like a family, a bit separated, like I was separated from everyone else in the family [29].

In the context of family sessions which permitted space for therapeutic focus on relationships, positive changes to family functioning were reported, including improved communication, cohesion and problem-solving skills; increased honesty, openness and closeness; mutual understanding and trust; emotional awareness and tolerance; reduced conflict, criticism and blame; and increased capability and compatibility [24, 29, 39, 54,55,56,57,58, 61, 62]. Having a safe, contained space for difficult conversations helped to reduce emotional disconnection:

They […] guided us through […] very hard conversations. Hard as in about feelings, about guilt, about perceptions, and about the effects it had on us […] I think as a family we’ve grown a lot closer […] [Parent, 38].

Families often described more space to focus on the family system within SyFT, FT-AN and flexibly adhered to FBT as oppose to strictly adhered to FBT [24, 53, 57, 62]. They valued the therapist’s directiveness on what needed to change, and their appreciation for each person’s feelings and views [24, 57]. These processes helped young people to share their feelings [24, 57]:

What helped most is to talk about my feelings without any reservation. She helped everyone to speak out, including those who didn’t talk much [Young person, 60].

Some young people felt that through the process of conversations which supported the family to engage with one another on an emotional level, they began to mentalise the experience of their parents and siblings which had a positive impact on their commitment to recovery [24, 57]:

I remember there was a little bit of guilt for what I was putting my parents through…and in a strange way, I kind of think that guilt was a motivator as well, because I was kind of like, I cannot keep doing this to my parents. They cannot live like this forever [24].

Some fathers became more involved in their young person’s life practically and emotionally through their involvement in treatment [29, 53, 58]. One young person described how her father’s involvement helped to reduce the disconnection between them:

[…] I can see that my father also tries to show concern for me. That feeling has been lost for years. He loves me and really wants to help me [53].

Siblings struggled to understand AN and wanted to be included in treatment [55, 56]. When siblings were not included, sibling-relationship ruptures were often left unrepaired causing young people to experience loss, sadness and guilt. Families reported positive aspects of sibling involvement, including increased understanding and unified support, increased closeness in the sibling relationship, reduced sibling worry, greater transparency in the family system and opportunity to clarify appropriate family roles [55]:

I think it made it so [sibling] understood […] what was going on. So it wasn’t like she was kept in the dark and we were trying to avoid talking about it to her. So she was a bit more aware of what was going on and she didn’t feel left out of it. She knew what not to say […] [55].

Complex family difficulties and relationships as a barrier to change

It was important that treatment addressed parental belief systems which served to maintain young peoples’ disordered relationships with eating and weight [38, 61]. One mother viewed slimness to confer protective factors for their young person and thus experienced challenge and unease during the process of refeeding. In order for treatment to facilitate weight restoration, the mother’s own beliefs in relation to eating and weight needed to be explored and addressed as an ongoing process:

The thinner you are, the more beautiful you are, the easier the world is for you. I truly…believe that. […] You want your kid to be….to fit in, […] and obviously that’s easier if you look a certain way […]. What if they’re wrong? What if they make her gain too much weight, and then…and then she feels like she’s…too heavy [61].

Young people did not perceive parental involvement to be helpful when they did not have trusting relationships with their parents, or when they had family difficulties which were not openly discussed in treatment [29, 56, 59]. They expressed uncertainty about what they were able to share due to concerns about disclosing their parents’ own difficulties, or revealing family conflict:

My parents have alcohol problems […] I preferred going on my own. […] the fact is I never told anyone at the eating disorder unit. […] I was so ashamed […] I was so dead scared of what might happen if they learnt about it [56].

These young people explained how there were difficulties which felt out of their control that they needed help with before letting go of control over their eating [59]; they described poorer relationships with parents, family conflict and high expressed emotions at home. Unresolved family difficulties and conflicts led to unrepaired ruptures and disconnection in their family relationships following treatment. Some families for whom relational change did not eventuate were experiencing grief, loss and trauma [29]. For example, one young person explained that previous abuse in the family impacted on her ability to trust her parents [30]:

[…] I didn’t trust my parents […] it would just have been so strange to have my mum sitting there. Then I would not have dared to be honest in the same way [56].

Discussion

This meta-synthesis explored the processes of change in family therapies for AN, elucidating factors that help and hinder recovery from the perspectives of young people and their families. The majority of studies explored young person and family member experiences of FBT, or SyFT; only one study explored the experience of FT-AN and this was from the perspectives of young people alone. The narratives depict several therapeutic processes which appear integral to facilitating positive change including psychological formulation, identity development beyond AN, the therapeutic relationship, emotional attunement, family involvement and family empowerment. These findings are discussed in relation to existing research, theory and their clinical implications.

Psychological formulation

Restriction provided young people with a sense of control over psychological and emotional difficulties, however it also resulted in the loss of agency and stalled development. Whilst FBT often failed to explore and address the psychological underpinnings of AN, parental re-feeding was often successful at supporting physical recovery and enabling young people to return to developmentally appropriate activities. This finding suggests an experience of change that aligns with proposed mechanisms of change within ED-focussed family therapy models [13, 14]. FBT and FT-AN aim to get the adolescent ‘developmentally back on track’ through the process of re-feeding which allows them to return to normal adolescent activities. Some young people experienced their return to valued activities reinforcing of their sense of personal agency which had a positive impact on their recovery. Research demonstrates how shifts in motivation for change occur in parallel with shifts in values and self-definitions through a process of identity renegotiation [66]. The findings alongside existing research underscore the significance of relinquishing control, self-discovery, and the development of a new identity in recovery from an ED which provides a false sense of security [67,68,69]. Accordingly, empowering young people to identify and return to developmentally appropriate activities that bring personal meaning and identity may help young people to connect with what is important to them and thereby support them in working towards and maintaining recovery. Ensuring that life outside of the ED is brought into treatment may help to aid such processes in order to facilitate positive change.

The findings underscore the importance of maintaining a holistic focus on the young person’s overall development in treatment, attending to their psychological, emotional, social and physical health to support positive change. Families often conveyed how FBT viewed the young person’s eating behaviours in isolation of their overall development which resulted in a perceived lack of understanding for the cause and maintenance of eating difficulties, and other associated difficulties. Therefore, the experience of families suggests that seeking to understand the young person’s eating difficulties within the context of their overall development is an important change mechanism in family therapies for AN. This finding does not align with what the FBT model proposes as a change mechanism. Rather, FBT takes an agnostic approach; it does not focus on exploring causes of AN and instead aims to engage the family in bringing about early behavioural change, assuming that an understanding of the cause does not necessarily translate to symptom improvement [17].

The finding that FBT’s agnostic aetiological stance does not alleviate parental guilt and blame is consistent with existing research. Carers are often perplexed by ANs cause, place blame on themselves and question their parenting [70, 71]. Hence, they place value on the opportunity to improve their understanding [72]. Caregiver cognitive appraisals relating to their understanding of AN are important because they have a direct impact on caregiver self-efficacy, the caregiving experience and their responses to the individual with AN [70]. This meta-synthesis suggests that some parents feel frustrated by FBT’s agnostic aetiological stance and continue to seek a causal explanation to make sense of their young person’s eating difficulties. Gorrell & Le Grange [73] state that the non-blaming foundation that ED-focussed family therapy models rest upon should not be confused within inattention to, and avoidance of exploring why struggles arise and persist. The authors state that treatment stagnation may be better understood if caregivers are invited to more directly speculate about how their own temperament, family attachment history, and distress tolerance may be getting in the way of positive change.

ED-focussed family therapy models place emphasis on externalising the ED as an ‘illness’ or external force to facilitate positive change. However, the findings suggest that the illness metaphor may have contributed to a neglect of psychological formulation for the young person’s eating difficulties in FBT. In turn, families experienced concern regarding FBT’s efficacy in meeting young peoples’ psychological and emotional needs. Some FBT clinicians experience the illness metaphor dilemmatic as it does not fit with their psycho-social understanding of EDs, however they continue to use it as recommended in the manual [74]. Baudinet, Simic and Eisler [18] underscore the importance psychological formulation in ED-focussed family therapy; proposing that it is through the formulation that treatment can be adjusted to target maintenance factors specific to individual families and that barriers to progress can be identified and overcome. Moreover, formulating collaboratively with a family can create a shared narrative about the problem and support the development of therapeutic alliance [75].

It has been proposed that AN arises from emotional processing difficulties resulting in a ‘lost sense of emotional self’ which ‘self-perpetuates’ and ‘relentlessly deepens’ [76]. Psychological factors including obsessive-compulsive personality traits, perfectionism, extreme need for self-control, cognitive rigidity, experiential avoidance, positive beliefs about the value/function of AN, and responses from close others play a significant role in its maintenance [77,78,79]. Developing a psychological formulation would help therapists to develop a holistic understanding of the young person within their family context, prioritise which issues to focus on, and select interventions to address not only the physical symptoms of AN, but also its psychological underpinnings and maintaining factors within family therapies for AN.

Positively, ED-focussed family therapy has been updated within FT-AN to consider the development of an evolving systemic formulation to be an important framework for thinking about change with the family throughout treatment. According to the FT-AN manual, the development of a systemic formulation includes consideration of (1) the nature of the problems that the young person and family are struggling with; (2) reorganisation of the family around the illness; (3) problem narratives, beliefs and cognitions; (4) emotions and feelings that may be connected to the illness; (5) mapping significant patterns; (6) strengths, resources and resilience factors. Further, the FT-AN model suggests that whilst eating and weight are likely to be the primary therapeutic focus at least initially, an important context for thinking about the process of change is to broaden the focus to other areas that are seen to contribute or perpetuate the ED, or are in other ways important to the family [14]. Therefore, the change mechanisms proposed by FT-AN may better aligned with what families perceive as being important factors in facilitating change through its attendance to young peoples’ eating behaviour within the context of their overall development and family environment. However, given that only one study exploring the experience of FT-AN was included within this review, it is difficult to ascertain whether FT-AN is more able than FBT to meet the needs of families and to thereby support positive change through its updated emphasis on formulation.

The therapeutic relationship

The finding that the therapeutic relationship is experienced as a crucial mechanism of change aligns with what ED-focussed family therapy models propose as being an important mechanism of change [13, 14]. The therapist’s knowledge, flexibility and willingness to come alongside them were conveyed by families as being particularly significant in supporting positive change. In contrast, negative experiences of the therapist acting as a ‘removed expert’ were viewed as a hinderance to positive change. In FBT the therapist takes up a non-authoritarian collaborative therapeutic stance [17]. They adopt the position of being an expert on EDs, while they view parents as being the expert in their young person and family in the hope of empowering parents to bring about recovery. The findings indicate that families valued the therapist taking up the position of expert in EDs as it enabled them to feel held and supported in managing the young person’s eating difficulties. However, they indicate that parents can experience a lack of containment in FBT when they perceive a lack of direct guidance from the therapist. This finding suggests that therapists’ attempts to build self-reliance by guiding and not giving explicit instructions may be experienced as challenging for parents when they are struggling to bring about change in their young person’s eating and weight and are in need of more direct guidance.

ED-focussed family therapy has been updated within FT-AN to initially emphasise engagement with the family and young person by creating a containing and secure base for treatment in which a shared sense of purpose is developed [14]. Accordingly, the FT-AN model acknowledges that the provision of expert advice can build dependency on the therapist but sees this as an appropriate aspect of the early stage of treatment with potential pitfalls that therapists should be aware of as treatment progresses. Therefore, it is possible that positive change may be helped by the provision of more direct guidance in the face of parental struggle with bringing about change in family therapies for AN. In doing so, families may experience the therapeutic relationship as a containing and secure base in which they can learn new skills and knowledges to manage their young person’s eating difficulties.

The findings support reviews which point to the significance of building trusting therapeutic relationships with young people and families [1, 27]. They also support studies which demonstrate significant associations between therapeutic alliance, treatment retention and outcome for individuals with AN [80,81,82,83]. Entering a therapeutic relationship required young people to relinquish control and place trust in others which necessitated the tolerance of heightened distress. A common theme raised by families is a concern about the lack of therapeutic alliance in treatment for AN [1, 84]. The findings in combination with existing research suggest that individuals want to feel seen and treated as a ‘whole person’, within a ‘real’ relationship with a therapist who is attuned to their emotional and psychological experiences rather than neglectful of their distress in the pursuit of weight restoration [1, 23, 25,26,27, 85, 86]. Attention to building and maintaining a strong therapeutic alliance with young people and their families by attending to and repairing ruptures, seeking to accurately understand their experiences, clarifying expectations and mutually agreeing treatment goals appear crucial to facilitating positive change.

Negative experiences of the therapeutic relationship were more common within manualised FBT than in SyFT, FT-AN, or flexibly adhered to FBT. Manual-based treatments have been criticised for contributing to ‘bland’, ‘rule governed’, and ‘emotionally detached’ therapy [87]. Clinical situations can differ from the tightly controlled conditions of a clinical research study in which evidence for a manual-based treatment is developed as clinicians are often required to adapt their practice to meet individual needs [88]. Therefore, it has been argued that while fidelity is a crucial component of successful evidence-based psychotherapy, flexible implementation allowing for deviation from the manual to individualise treatment is necessary [89]. The findings alongside existing research stress a need for greater flexibility in the delivery of manualised FBT. Nevertheless, despite being a manual-based treatment, FT-AN appeared to be experienced more positively by young people within this review. Thus, FT-AN may be superior to FBT in its ability to establish and maintain positive therapeutic relationships through its emphasis on engagement with all family members from the outset and use of formulation to individualise treatment.

Emotional attunement

The finding that positive change was hindered by the experience of confinement in focus on food intake and weight does not align with change mechanisms proposed by ED-focussed family therapy models. FBT in particular takes a pragmatic approach maintaining a ‘laser like focus’ on symptom reduction to elicit change [17]. Hence, emotional and psychological distress which is perceived by the therapist as secondary to the ED is not visited until ‘the crisis is over’ and the young person is physically well. In doing so, the intention is to remain focussed on eating behaviours to support the restoration of physical health which is thought to lead to the alleviation of emotional and psychological distress related to the ED. Concerningly, the narratives of young people and families who engaged in FBT depict an experience of treatment which was at times neglectful of their distress as a consequence of this focus.

The updated ED-focussed family therapy model, FT-AN, views the containment and validation of family anxiety as crucial in supporting positive change (Eisler et al., 2016). The model proposes that therapists need to be aware of how a decrease in anorexic cognitions does not necessarily run in parallel with weight gain. Further, that for some young people anorexic cognitions and other difficulties (e.g., anxiety, ocd and depression) may become more difficult as weight increases, causing distress for both the individual and family. FT-AN suggests that for young people in this situation, offering coinciding individual therapy could be beneficial within phase three. However, young people who engaged in FT-AN described a need for treatment to attend more to their internal experiences within the earlier phases of treatment as they were more parent-focussed. Therefore, positive change in family therapies for AN may be supported by increasing their attention to the emotional experiences of the young person in the earlier phases of treatment. A focus on emotional attunement alongside the focus on the restoration of physical health through increasing food intake and weight may support young people’s engagement throughout the entirety of treatment through aiding the development of a therapeutic relationship in which the young person experiences a sense of emotional containment.

Many young people reported to feel that what they were experiencing internally “did not matter” within FBT. Some healthcare professionals (HCPs) treating AN feel that the biomedical model supports them to define target symptoms and goals for recovery, however families perceive the model to place too much focus on the physical, ignoring psychological distress [27]. This meta-synthesis alongside existing research illustrates how families seek a holistic individually-adapted treatment that is flexible, and considers the psychology of the young person’s eating behaviour, as well as their family environment [1, 23, 25, 27]. Some FBT clinicians assume that weight restoration is the primary agent of cognitive symptom relief through the alleviation of cognitive rigidity resulting from starvation [90]. However, this meta-synthesis alongside existing research suggests that the psychological experience of AN can persist beyond weight restoration [90]. Thus, therapists should be cognisant of the messages conveyed to families through holding this assumption as they may risk invalidating their lived experiences and hindering the alliance. The findings suggests that whilst ED-focussed family therapies can support weight restoration, many young people experience ongoing difficulties in their relationship to eating and weight which they would like support for within individual therapy, alongside and/or following completion of family therapy for AN.