Abstract

Background

Positive changes in weight gain and eating pathology were reported after inpatient treatments for anorexia nervosa (AN). However, changes in the physical body do not always mirror changes in the imagined body. Here, the effect of a treatment focused on body image (BI) was described.

Methods

This retrospective observational study had a quasi-experimental pre-post design without the control group. During the treatment, participants (N = 72) undertake a variety of activities focused on BI. The main outcome was tested through the Body Uneasiness Test.

Results

At the end of the treatment, BI uneasiness decreased with a significant increase in weight gain.

Conclusion

This study highlights the positive short-term effect of a multidisciplinary inpatient intensive rehabilitation treatment on BI in AN. We encourage to design of psychological treatments focusing on the cognitive and emotional bodily representation (i.e. the body in the mind) to increase physical well-being.

Plain English Summary

The sufferance of people affected by anorexia nervosa (AN) relies on different levels. Despite weight and eating habits being the most recognizable components of AN, people affected by AN can experience a very negative body image. The study highlights how a multidisciplinary inpatient intensive rehabilitation treatment for treating AN positively affects body image. Body image was targeted by specific activities, such as body image therapy and dance movement therapy. Rehabilitation programs should propose activities focusing on treating the cognitive and emotional bodily representation (i.e. the body in the mind) to increase physical well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Most of the inpatient treatments for anorexia nervosa (AN) for both adolescents and adults reported in the literature are designed to promote changes in weight gain and reduction of eating pathology [1, 2] since they are severely compromised in the disease [3, 4]. However, increased weight as well as improved eating habits do not always mirror positive changes in psychopathology, and sometimes affected people are resistant to changes [5,6,7,8]. One factor that may contribute to the efficacy of treatment is the negative body image (BI), meaning the complexity of beliefs, thoughts, perceptions, feelings, and behaviors towards the body [9, 10] typically observed in AN. Thus, this retrospective study aimed to verify the short-term effects of an inpatient intensive rehabilitation treatment for AN focused on BI.

Methods

This retrospective observational study had a quasi-experimental pre-post design without the control group (for a similar approach see [11]). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the involved Institution (Reference number: 2022_11_22_05). All participants were volunteers who gave informed written consent before participating in this study; in the case of an age below 18 years old, parents signed the written consent. The Italian National Sanitary System covers all hospital charges and participants were not remunerated.

Sample

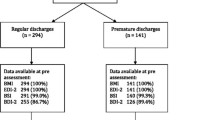

Only in-patients consecutively recruited at their admission to the hospital between August 2021 and July 2022 (12 months) were included. Individuals were included in this study if (i) they were diagnosed with AN [3]; (ii) their body mass index (BMI) was ≤ 17 kg/m2 at the time of the admission (i.e. only moderate to extreme conditions [3]); (iii) they were compliant with the rehabilitation program; (iv) AN was the primary psychopathological diagnosis. Participants were excluded if (i) they withdrew from the program; (ii) other pathologies non-AN related were recorded (e.g. neurodegenerative diseases such as brain injury, and stroke); (iii) self-report questionnaires at admission or discharge were not completed. Notably, individuals in their first recovery and those in their second or more recovery were included: as the chronic nature of the disease [12], affected individuals frequently undertake more than one treatment.

Multidisciplinary inpatient intensive rehabilitation treatment’s description

Individuals participated in a residential program for three to eight weeks (Table 1).

The treatment is multidisciplinary, proposing both individual and in-group sessions focusing on the bodily experience; also, psychological functioning and nutrition are targeted. Body image difficulties were treated through BI therapy [13] and group dance therapy [14], since some previous evidence [15,16,17]. Also, low-intensity physical activities were proposed: individuals with AN sometimes experience the urge to move [18,19,20] and physical restlessness, with negative consequences on weight. Thus, physical movements were targeted as part of a healthy lifestyle.

Psychological functioning (e.g. depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic symptomatology) was targeted through both individual and in-group psychotherapy [21]. Finally, individual and in-group consultations with nutrition experts were delivered to identify tailored dietary schemes and to promote nutritional education about biological hunger, satiety, and nutrients [22]. Participants attended also assisted meals.

Measures

All the psychological measures were completed at T0 (at the beginning of the treatment) and T1 (at the end of the rehabilitation program). The main outcome of the treatment (i.e. BI) was measured through the Body Uneasiness Test (BUT) [23], which assessed the individual level of discomfort towards their own body and BI. The questionnaire consists of 71 items, split into two parts with a six-point Likert scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often, usually, and always). Part A refers to weight phobia, body image concerns, avoidance, compulsive self-monitoring, detachment, and feelings of estrangement towards one's own body (i.e. depersonalization); part B measures specific worries about body parts or functions. The higher the score, the greater the body discomfort.

Moreover, as secondary outcomes, the pathological eating behavior through the Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3) questionnaire [24], the psychological well-being through the Psychological General Well-Being Index questionnaire (PGWBI) [25], and the psychopathological components through the Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90) [26] were measured. Details about these questionnaires (i.e. description and results) are reported in Additional file 1.

Analyses

All the questionnaires (secondary outcomes included) were scored according to the seminal articles. A repeated measure analysis of covariance was used to highlight possible differences between the T0 and T1 (Time: T0 vs T1; main factor—within subjects) for each score, including delta (Δ) BMI (ΔBMI: T1-T0) as covariate to control the impact of BMI changes on the main within-subject factor of Time. Because of the high level of malnourishment, small variations in BMI may be observed over time. However, patients are very triggered by changes in their weight, which may have a not directly measurable effect on the outcomes. A paired sample t-test was used to verify any difference in the level of BMI registered at T0 and T1 within the two groups.

Pearson’s correlation was used to verify the relationship between the Δ score (Δ = T1-T0) of the Global Severity Index from BUT and the other outcomes tested (i.e. eating pathology by the Eating Concerns Composite scale (EDI-3), Global score PGWBI for the psychological well-being, and the Obsessive–compulsive, Depression, Anxiety, and Global indices of distress from the SCL-90 (other psychopathologies). Indeed, changes in BI may be related to changes in the other components treated in the intervention. Significant results were considered for p value ≤ .05 (two-tailed).

Because of ethical reasons, there is no restriction on age for admission to the rehabilitation program. Moreover, the length of recovery might differ because of the individual’s needs (i.e. tailoring approach). Therefore, in two supplementary analyses assessing, the main analysis relative to the main outcome of BI was run including these two factors as covariate (independently tested) Results are included respectively within Additional file 2 and Additional file 3.

Results

Participants

Overall, the information relative to 80 participants with AN was retrospectively inspected to be considered for this study; however, only 90% of participants were included, while 10% of the sample were excluded from the analyses because they dropped out from the rehabilitation program. The final dataset consisted of seventy-two participants with AN (type: 75% restrictive vs 25% binge-purging; 68 females; age: average (M) = 24.13, Standard Deviation (SD) = 12.43, min–max = 13–66); level of education: middle school N = 9, high school N = 51, bachelor’s degree N = 6, master’s degree N = 6; age at disease onset: M = 16.19, SD = 5.94, min–max = 10–50; disease length (from onset) in years: M = 7.93, SD = 10.76, min–max = 0–42). The mean of days of treatment was 36 (SD = 9 days). The mean level of BMI expressed as kg/m2 at the admission was 14.13 (SD = 1.58, min–max = 9.73–16.87), whereas at the discharge was 14.49 (SD = 1.45, min–max = 10.22–17.56): a significant increase after the treatment emerged (t(71) = 3.92; p < .001; d = .77).

Main outcome: body image

For all the scales of BUT-A, scores from T0 to T1 (significant main effect of Time) decreased (Table 2), suggesting an amelioration in all the tested components. Also, the amelioration in the Global Severity Index and Weight phobia was still observed, also when controlling for the individual BMI variation ((a significant main effect of the covariate). No significant main effect of Time (no difference between scores at T0 and T1) or of the covariate (Table 2) were observed for the BUT – part B.

Secondary outcomes

As reported in Additional file 1, significant positive changes were observed also in eating pathology, psychological well-being, and more general psychological sufferance. This mirrored previous literature on the topic [27,28,29,30].

Relationship between outcomes

As shown in Table 3, a significant positive relationship emerged between the ΔGlobal Severity Index (BUT), and the Δ scores of the ΔEating Concerns Composite (EDI-3), ΔObsessive-compulsive (SCL-90), ΔDepression (SCL-90), ΔAnxiety (SCL-90), and ΔGlobal indices of distress (SCL-90). Differently, a significant negative relationship between the ΔGlobal Severity Index (BUT) and the ΔGlobal score PGWBI was observed.

Overall, the decrease in body uneasiness experienced after the treatment was significantly related to positive changes in terms of eating pathology, psychological stress (i.e. obsessive–compulsive, depressive, and anxiety symptoms) as well as psychological well-being.

The role of age and length of recovery

As reported in the Supplementary materials, the main effect of the treatment on BUT was still significant, also when controlling for the covariate age; differently, we did not observe a significant main effect of the treatment when controlling for the length of recovery.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to verify the short-term within-group effects of a multidisciplinary inpatient intensive rehabilitation treatment on BI in a sample of individuals affected by AN.

After the treatment, changes in BI were observed, as suggested by the positive increase in the scores relative to all the components of BUT—part A [23], together with decreased psychopathological eating symptoms and increased psychological well-being (see Additional file 1). The multidisciplinary treatment includes activities designed to mitigate body misperception in AN, fostering the acceptance of bodily changes and the decrease of cognitive bodily distortions [31] through multiple positive experiences involving body actions: patients may perceive positive sensorimotor feedback from their own body when engaged in imagined and physical movements.

Notably, it was not observe any changes for part B of BUT, which measures specific worries about particular body parts or functions. The rehabilitation activities were not focused on single body parts, since it was aimed to help participants experience the body as a whole, to decrease self-monitoring and checking behavior [32, 33]. Together with a more positive BI perception, the physical body changed in participants with an increased BMI after the treatment. It may be expected that BI would be negatively influenced by weight gain [7, 8]: individuals with AN would be highly worried about seeing weight increase. This may be not the case, since changes in the physical body were sustained by positive changes in cognitive and emotional bodily representation (i.e. BI) [23]. The results about the physical body and imagined body recall the concept according to which the body cannot be dissociated from the mind, and vice versa [34]. Both components are crucial in the individual bodily experience, specifically in the case of illness: AN does not concern only the physical body, but also how the body is mentally thought and represented [35]. This is something that should be taken more into account in designing rehabilitative treatments for AN [36, 37], as here proposed.

The current study presents some limitations. Here, it was a monocentric-based study, as done elsewhere [1, 29, 30]; therefore, such results should be generalized with some caution. A control group (i.e. not-treated affected individuals) was not included because of ethical reasons [11, 38]: during hospitalization, treatments must be guaranteed for each patient. Only self-report measurements, even though they are highly used in clinical and research contexts, were used as outcomes. Lastly, only people compliant with the rehabilitation program were included in the sample: it was recorded that approximately 10% of patients dropped out of the program. Drop-out from inpatient programs is something well-known in the literature [39]; however, the reasons for the drop-out (i.e., noncompliance, disease worsening requiring access to the emergency room, or other external factors) and when participants retired from the program are generally not recorded. However, what factors may anticipate the drop-out should be analyzed to increase the efficacy of the treatment and maximize the inclusion of participants in the program.

Conclusions

The study highlighted the positive short-term effect of a multidisciplinary inpatient intensive rehabilitation treatment on BI, together with increased BMI and amelioration of eating pathology and psychological well-being, in individuals with AN. The results of the study may encourage to design psychological treatments focusing on BI, even in the case of very low BMI: restoring a positive cognitive and emotional bodily representation (the body in mind) may increase physical and psychological well-being.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request in Zenodo at: https://zenodo.org/record/8297953.

Abbreviations

- AN:

-

Anorexia nervosa

- BI:

-

Body image

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BUT:

-

Body uneasiness test

- EDI-3:

-

Eating disorder inventory-3

- M:

-

Average

- PGWBI:

-

Psychological general well-being index

- SCL-90:

-

Symptom check list-90

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SE:

-

Standard error of the mean

References

Meule A, Schrambke D, Furst Loredo A, Schlegl S, Naab S, Voderholzer U. Inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa in adolescents: a 1-year follow-up study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;29(2):165–77.

Peckmezian T, Paxton SJ. A systematic review of outcomes following residential treatment for eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2020;28(3):246–59.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edn) (DSM-5). Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Hay P. Current approach to eating disorders: a clinical update. Intern Med J. 2020;50(1):24–9.

Goddard E, Hibbs R, Raenker S, Salerno L, Arcelus J, Boughton N, et al. A multi-centre cohort study of short-term outcomes of hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa in the UK. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):287.

Schlegl S, Quadflieg N, Löwe B, Cuntz U, Voderholzer U. Specialized inpatient treatment of adult anorexia nervosa: effectiveness and clinical significance of changes. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):258.

Espeset EM, Nordbø RH, Gulliksen KS, Skårderud F, Geller J, Holte A. The concept of body image disturbance in anorexia nervosa: an empirical inquiry utilizing patients’ subjective experiences. Eat Disord. 2011;19(2):175–93.

Exterkate CC, Vriesendorp PF, de Jong CAJ. Body attitudes in patients with eating disorders at presentation and completion of Intensive Outpatient Day treatment. Eat Behav. 2009;10(1):16–21.

Mangweth-Matzek B, Hoek HW, Pope HG. Pathological eating and body dissatisfaction in middle-aged and older women. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(6):431–5.

Sattler FA, Eickmeyer S, Eisenkolb J. Body image disturbance in children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a systematic review. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorexia Bulimia Obesity. 2019;25(4):857–65.

Scarpina F, Bastoni I, Cappelli S, Priano L, Giacomotti E, Castelnuovo G, et al. Short-term effects of a multidisciplinary residential rehabilitation program on perceived risks, confidence toward continuous positive airway pressure treatment, and self-efficacy in a sample of individuals affected by obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Front Psychol. 2021;12:703089.

Hay PJ, Touyz S, Sud R. Treatment for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: A Review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(12):1136–44.

Alleva JM, Sheeran P, Webb TL, Martijn C, Miles E. A meta-analytic review of stand-alone interventions to improve body image. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0139177.

Koch S, Kunz T, Lykou S, Cruz R. Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. Arts Psychother. 2014;41(1):46–64.

Keizer A, Engel MM, Bonekamp J, Van Elburg A. Hoop training: A pilot study assessing the effectiveness of a multisensory approach to treatment of body image disturbance in anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorexia Bulimia Obesity. 2018;24(5):953–8.

Savidaki M, Demirtoka S, Rodríguez-Jiménez R-M. Re-inhabiting one’s body: a pilot study on the effects of dance movement therapy on body image and alexithymia in eating disorders. J Eat Disord. 2020;8(1):22.

Ziser K, Mölbert SC, Stuber F, Giel KE, Zipfel S, Junne F. Effectiveness of body image directed interventions in patients with anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(10):1121–7.

Casper RC, Voderholzer U, Naab S, Schlegl S. Increased urge for movement, physical and mental restlessness, fundamental symptoms of restricting anorexia nervosa? Brain Behav. 2020;10(3):e01556.

Melissa R, Lama M, Laurence K, Sylvie B, Jeanne D, Odile V, et al. Physical activity in eating disorders: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2020;12(1):183.

Pieters G, Vansteelandt K, Claes L, Probst M, Van Mechelen I, Vandereycken W. The usefulness of experience sampling in understanding the urge to move in anorexia nervosa. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2006;18(1):30–7.

Madden S. Systematic review of evidence for different treatment settings in anorexia nervosa. World J Psychiatry. 2015;5(1):147.

Zipfel S, Giel KE, Bulik CM, Hay P, Schmidt U. Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(12):1099–111.

Cuzzolaro M, Vetrone G, Marano G, Garfinkel PE. The body uneasiness test (but): development and validation of a new body image assessment scale. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorexia Bulimia Obesity. 2006;11(1):1–13.

Clausen L, Rosenvinge JH, Friborg O, Rokkedal K. Validating the eating disorder inventory-3 (EDI-3): a comparison between 561 female eating disorders patients and 878 females from the general population. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;33(1):101–10.

Dupuy HJ. The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) Index. In: Wenger N, editor. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. New York: Le Jacq; 1984. p. 170–83.

Sarno I, Preti E, Prunas A, Madeddu F. SCL-90-R. Symptom checklist-90-R. Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze; 2011.

de Vos JA, Radstaak M, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Having an eating disorder and still being able to flourish? Examination of pathological symptoms and well-being as two continua of mental health in a clinical sample. Front Psychol. 2018;9:2145.

Abbate-Daga G, Marzola E, De-Bacco C, Buzzichelli S, Brustolin A, Campisi S, et al. Day hospital treatment for anorexia nervosa: a 12-month follow-up study. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(5):390–8.

Brewerton TD, Costin C. Treatment results of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in a residential treatment program. Eat Disord. 2011;19(2):117–31.

Long CG, Fitzgerald K-A, Hollin CR. Treatment of chronic anorexia nervosa: a 4-year follow-up of adult patients treated in an acute inpatient setting. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;19(1):1–13.

Sala L, Mirabel-Sarron C, Pham-Scottez A, Blanchet A, Rouillon F, Gorwood P. Body dissatisfaction is improved but the ideal silhouette is unchanged during weight recovery in anorexia nervosa female inpatients. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorexia Bulimia Obesity. 2012;17(2):e109.

Beckmann N, Baumann P, Herpertz S, Trojan J, Diers M. How the unconscious mind controls body movements: body schema distortion in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2021;54(4):578–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23451.

Calugi S, El Ghoch M, Dalle GR. Body checking behaviors in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(4):437–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22677.

Carruthers G. Types of body representation and the sense of embodiment. Conscious Cogn. 2008;17(4):1302–16.

Scarpina F, Bastoni I, Villa V, Mendolicchio L, Castelnuovo G, Mauro A, Sedda A. Self-perception in anorexia nervosa: when the body becomes an object. Neuropsychologia. 2022;166:108158.

Magrini M, Curzio O, Tampucci M, Donzelli G, Cori L, Imiotti MC, et al. Anorexia nervosa, body image perception and virtual reality therapeutic applications: State of the art and operational proposal. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(5):2533.

Serino S, Chirico A, Pedroli E, Polli N, Cacciatore C, Riva G. Two-phases innovative treatment for anorexia nervosa: the potential of virtual reality body-swap. Annu Rev Cyber Therapy Telemed. 2017;15:111–5.

Manzoni GM, Villa V, Compare A, Castelnuovo G, Nibbio F, Titon AM, et al. Short-term effects of a multi-disciplinary cardiac rehabilitation programme on psychological well-being, exercise capacity and weight in a sample of obese in-patients with coronary heart disease: a practice-level study. Psychol Health Med. 2011;16(2):178–89.

Hubert T, Pioggiosi P, Huas C, Wallier J, Maria AS, Apfel A, Curt F, Falissard B, Godart N. Drop-out from adolescent and young adult inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):632–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Italian Ministry of Health—Ricerca Corrente.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BF: conception of the work, design of the work, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, have drafted the work. SF: conception of the work, design of the work, data interpretation, have substantively revised the work. BI: conception of the work, data acquisition. VV: conception of the work, design of the work. CG: conception of the work, design of the work, supervision of the data collection and activities. AE: conception of the work, clinical assessment of participants. SS: conception of the work, clinical assessment of participants. ML: conception of the work, design of the work, data interpretation, scientific and clinical supervision of the entire project, have substantively revised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of the Istituto Auxologico Italiano approved the study (Reference number: 2022_11_22_05) and the study was conducted in accordance with the latest Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. All participants were volunteers who gave informed written consent before participating in this study, in the case of underage (an age below 18 years old) the written consent was signed by parents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Supplementary analyses-secondary outcomes.

Additional file 2

. Supplementary analyses-covariate: age.

Additional file 3

. Supplementary analyses-covariate: length of recovery.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Federico, B., Federica, S., Ilaria, B. et al. Short-term effects of a multidisciplinary inpatient intensive rehabilitation treatment on body image in anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord 11, 178 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00906-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00906-9