Abstract

Background

Transgender youth and young adults are at increased risk for eating disorders, including binge eating disorder, yet few measures have been validated for screening purposes with the transgender population.

Methods

The purpose of this study was to provide initial evidence for the internal consistency and convergent validity of the Adolescent Binge Eating Disorder questionnaire (ADO-BED) in a sample of transgender youth and young adults. 208 participants completed the ADO-BED as part of a routine nutrition screening protocol at a gender center. Exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis was used to establish the factor structure of the ADO-BED. Relationships between the ADO-BED, Sick, Control, One Stone, Fat, Food (SCOFF), Nine Item Avoidant/restrictive Intake Disorder (NIAS), Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), and demographic characteristics were explored.

Results

Analyses revealed a one-factor structure of the ADO-BED with good fit to the data in the present sample. The ADO-BED was shown to be significantly related to all convergent validity variables, except the NIAS.

Conclusions

The ADO-BED is a valid measure to screen for BED among transgender youth and young adults. Healthcare professionals can screen all transgender patients for BED, regardless of body size, in order to effectively identify and manage binge eating concerns.

Plain English Summary

Transgender individuals are at increased risk for eating disorders, including binge eating disorder. Different questionnaires are used to screen people for eating disorders to know if they need additional evaluation. However, few of the existing questionnaires commonly used to screen for eating disorders have been tested with the transgender population. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine if one questionnaire, the Adolescent Binge Eating Disorder questionnaire (ADO-BED), is an accurate measure to screen for binge eating disorder among transgender youth and young adults. The results of this study supported that the ADO-BED is indeed a valid measure to use with transgender patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eating disorders disproportionately impact the transgender and gender expansive population compared to the cisgender population [1, 2]. Estimates of prevalence range from 2 to 35% of transgender youth and young adults [1, 3]. Theorized rationale for disordered eating among the transgender population include: a desire to attain or suppress body features that align with one’s authentic gender identity; menstrual suppression; pubertal suppression; and a coping mechanism for psychological distress related to minority stress, discrimination and victimization. [1,2,3,4,5,6]

Emerging research has provided greater specificity regarding prevalence of specific types of eating disorders and related behaviors, including binge eating disorder (BED). Among a clinical sample of youth and young adults presenting to a Midwestern gender clinic, 9% screened positive for BED using the Adolescent Binge Eating Disorder questionnaire (ADO-BED) [6]. Among adolescents at a Seattle-based gender clinic, 26% reported binge eating using selected questions from the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [7]. Within a national sample of sexual and gender minority adults, 10% of transgender men, 14% of transgender women, and 12% of gender expansive participants reported binge eating in the past month [8].

Prevalence estimates of diagnosed BED are notably lower than estimates of reported binge eating. Ferrucci and colleagues reported that less than 1% of transgender patients within a medical claims database were diagnosed with BED, though this population had health insurance and access to gender-affirming care [9]. Schvey and colleagues estimated that 2.6% of sexual and gender minority children had BED, a rate three times higher than their non-sexual and gender minority peers. 10]

To address the elevated risk for eating disorders, scholars have underpinned the need to screen transgender patients for eating disorders. However, implementation of this recommendation is limited by the lack of measures validated with transgender populations [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Validation of eating disorder questionnaires among transgender populations is needed to inform accurate and culturally appropriate screening practices.

Study purpose and aims

The purpose of this study was to provide initial evidence for the internal consistency and convergent validity of the ADO-BED in a sample of transgender youth and young adults. The ADO-BED was selected given its utility in specifically screening for BED, rather than broadly screening for eating disorders such as the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) or the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaires (EDE-Q). Furthermore, the ADO-BED was initially validated with an adolescent population, which aligns with the patient population at the study site and other transgender centers that care primarily for youth.

The study aims were to (1) establish and confirm the factor structure of the ADO-BED and (2) explore convergent and divergent validity of the ADO-BED with commonly used measures of anxiety, depression, and disordered eating, and with body mass index percentile.

Methods

Participants and setting

Returning patients at the Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children's Hospital transgender center (n = 208) ages 11–22 completed the ADO-BED as part of a nutrition screening protocol for eating disorders and food insecurity. Data were collected from January 2021-June 2022; details of the nutrition screening protocol have been previously reported [6]. The GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were completed as part of routine mental health screening. Additional data collected from electronic medical records included age, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, weight, and height. The Institutional Review Board of the Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children's Hospital provided a waiver of consent given that the nutrition screening is the standard of care.

Measures ADO-BED

The ADO-BED is a brief, ten-item measure used to screen for binge eating disorder among adolescents with obesity. Its original development utilized a sample of 94 adolescents ages 12–18 from Geneva University Hospitals in Geneva, Switzerland. A positive answer to either of the first two questions related to 1) eating when not hungry and 2) loss of control overeating was significantly associated with subclinical or clinical BED status when compared to a clinical interview. For scoring purposes, the authors of the ADO-BED identified a high risk of subclinical and clinical BED among participants who responded positively (yes) to questions one or two, and had more than 6 positive answers to the eight additional questions [11].

Sick, control, one stone, fat, food (SCOFF)

The SCOFF is a five-item measure used to screen for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Scores of 0–5 are used to estimate eating disorder risk [12, 13]. The SCOFF was selected given its brevity and therefore utility at the transgender center, as well as its validation among many racially/ethnically and geographically diverse populations [12, 13].

Nine item avoidant/restrictive intake disorder (NIAS)

The NIAS is a nine-item measure used to screen for avoidant/restrictive intake disorder (ARFID) among adolescents and adults, including transgender populations. Scores of 0–45 are used to characterize three restrictive eating patterns, including picky eating, poor appetite or limited interest in eating, and fear of eating consequences [14, 15].

Generalized anxiety disorder 7 (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 is a seven-item measure used to screen for generalized anxiety disorder. Scores of 0–21 are used to quantify the degree of anxiety from minimal to severe [16].

Patient health questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a nine-item measure used to screen for depression. Scores of 1–27 are used to quantify the degree of depression from minimal to severe [17].

Body mass index (BMI)

BMI was calculated using clinic-measured height and weight. Among youth ages 12–19, BMI percentile (BMI%) was reported using the boy or girl growth chart consistent with sex assigned at birth if the patient was on puberty blockers, and/or not on hormone therapy (HT). For patients who were on HT, BMI% was reported using both growth charts. Among young adults ages 20–22, BMI was reported and did not require sex-specific interpretation [18].

Analytic approach

Using SPSS version 29 and R version 4.2.2, an exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis were used to establish and confirm the fit of the ADO-BED survey in the current dataset. The exploratory factor analysis was used to establish the factor loadings. Principal components extraction and oblique rotation were used to interpret the factor loadings, as the items were assumed to be related [19]. Decisions regarding the number of factors to extract were based on eigenvalues < 1 [20], and a visual examination of the scree plot. Significant Bartlett’s test of Sphericity and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic > 0.5 were used to evaluate the data and factor loadings > 0.4 were considered acceptable for the inclusion of each item in a factor.

The confirmatory factor analysis was fit with a diagonal weighted least squares estimator (DWLS) using the R lavaan package [21]. DWLS was chosen since the data was measured on a categorical scale and the positive skew of the ADO-BED. Goodness of fit of the model was evaluated by the following criteria: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.05, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.90, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.08 [22]

In order to determine convergent validity, zero-order correlations between the ADO-BED and the convergent validity variables were calculated. These variables include the SCOFF, NIAS, PHQ-9, GAD-7, BMI, BMI %based on sex assigned at birth, and BMI%based on gender identity.

The reliability of the ADO-BED was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha.

Results

The sample of participants (n = 208) was 11–22 years old with an average age of 15.43 years (SD = 1.86). Participants were assigned female at birth (72.6%) or assigned male at birth (27.4%). Regarding gender identity, participants were transgender female/transfeminine (25.5%), transgender male/transmasculine (55.0%), nonbinary (16.8%), agender (1.4%), or other terms (1.4%); some participants reported multiple gender identity terms, therefore the percentages exceeded 100%. Using BMI or BMI% and the growth chart consistent with sex assigned at birth, the study sample was 4.3% underweight, 54.4% healthy weight, 12.5% overweight, and 28.8% obese (Fig. 1).

Weight status of the study sample. Group 1: Assigned Male at Birth (AMAB), Puberty Blockers Only and/or No Hormone Therapy. Group 2: Assigned Male at Birth (AMAB), Puberty Blockers Only and/or No Hormone Therapy. Group 3: AMAB, Medical Transition, Growth Chart Consistent with Sex. Group 4: AFAB, Medical Transition, Growth Chart Consistent with Sex. Group 5: AMAB, Medical Transition, Growth Chart of Opposite Sex (Female). Group 6: AFAB, Medical Transition, Growth Chart of Opposite Sex (Male). Total: All Participants, Growth Chart Consistent with Sex

Using the scoring criteria of the ADO-BED authors, 13.5% of participants in this study screened positive for clinical or subclinical BED. Slightly more participants (14.4%) responded positively to the question regarding compensatory behaviors (“When you are in these situations do you sometimes need to take action to eliminate what you have just eating [exercise, skip the next meal, self-induce vomiting…]) [11].

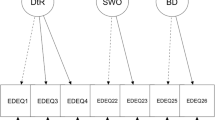

The structure of the ADO-BED within the transgender adolescent sample was explored using a principal components factor analysis with oblique rotation. This revealed a one-factor structure with eigenvalues of > 1, which explained 60.13% of the variance. The data appeared to be well suited for factor analysis as indicated by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin statistic (0.92) and the significant Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, X2 (45) = 1195.66, p < 0.001 [23,24,25]. Factor loadings on individual questions were satisfactory: Q1 = 0.856, Q2 = 0.759, Q3 = 0.759, Q4 = 0.712, Q5 = 0.842, Q6 = 0.865, Q7 = 0.834, Q8 = 0.760, Q9 = 0.658, and Q10 = 0.675.

Following the EFA, a confirmatory factor analysis was used for the 1-factor model. Goodness-of-fit-indices supported the one-factor model, which showed good fit to the data: non-significant chi-square, RMSEA = 0.00 [0.00, 0.00], CFI = 1.00, SRMR = 0.054.

See Table 1 for zero-order correlations between the SCOFF and convergent validity variables. There was a significant moderate correlation between the ADO-BED and the SCOFF, and small but significant correlations between the ADO-BED and the PHQ-9, the GAD 7, BMI, BMI% based on sex assigned at birth, and BMI% based on gender identity. The ADO-BED was not significantly related to the NIAS. Reliability was also assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which was 0.926.

Discussion

BED is often underdiagnosed by healthcare professionals relative to other eating disorders, in part due to relatively new diagnostic criteria and limited screening tools [26, 27]. Other validated screening tools specific to BED include the Binge Eating Scale (BES), the Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BEDS-7), and the Children’s Binge Eating Disorder Scale (C-BEDS) [28,29,30]. However, these measures have not been validated with the transgender population.

The study findings support that the ADO-BED is a valid measure to screen for BED among transgender youth and young adults ages 11–22 at any weight status. The positive correlation between the ADO-BED and the SCOFF confirms similarities between these measures, such as loss of control over eating or eating under uncomfortably full [11, 12]. The positive correlation between the ADO-BED, BMI and BMI% confirms that patients with BED may have overweight or obesity, though BED can manifest in patients without obesity [31]. A notable proportion (13.5%) of the study sample screened positive for clinical or subclinical BED, and is therefore worthwhile to routinely screen.

Given that the ADO-BED only screens for BED, healthcare professionals can use this measure in tandem with other measures to screen for eating and feeding disorders including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. A notable proportion of participants responded positively to the question regarding compensatory behaviors, which distinguishes BED from bulimia nervosa. Routine screening at gender centers or other facilities that routinely care for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) population can increase the likelihood of detecting and managing eating concerns [6].

The results of this study supported that ADO-BED scores were positively correlated with BMI and BMI%. However, all patients should be screened for eating disorders given that BED manifests in populations with and without obesity and often causes significant distress independent of the impact on body weight [31]. Although the ADO-BED was originally validated with adolescents with obesity, this study sample included underweight, healthy weight, overweight and obese participants. Healthcare providers can prepare for how positive ADO-BED screens will be addressed. This may include: Further evaluation of eating patterns and weight history; evaluation for comorbidities such as diabetes and dyslipidemia; and referral to medical, mental health, and allied health professionals trained in gender-affirming care.

Strengths, limitations and future research

Given that many studies report eating disorder-related data based on a binary view of gender [26], a strength of this study was the gender diverse sample with participants who identified as transgender male, transgender female, non-binary, and genderqueer, among others. This study was limited by data collection at a single site; responses may have varied at other geographical regions within and outside of the United States. Further research can better estimate BED prevalence, especially among patients without obesity, and explore culturally appropriate prevention and treatment approaches.

Conclusions

The ADO-BED is a valid measure to screen for BED among transgender youth and young adults ages 11–22 at any weight status. Healthcare professionals can screen all transgender patients for BED, regardless of body size, in order to effectively identify and manage binge eating concerns.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to HIPAA protections but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADO-BED:

-

Adolescent binge eating disorder questionnaire

- SCOFF:

-

Sick, control, one stone, fat, food

- NIAS:

-

Nine item avoidant/restrictive intake disorder

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient health questionnaire 9

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized anxiety disorder 7

- BED:

-

Binge eating disorder

- EDE-Q:

-

Eating disorder examination questionnaire

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BMI%:

-

BMI percentile

- HT:

-

Hormone therapy

- KMO:

-

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

- DWLS:

-

Diagonal weighted least squares estimator

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- SRMR:

-

Standardized root mean square residual

- BES:

-

Binge eating scale

- BEDS-7:

-

Binge eating disorder screener

- C-BEDS:

-

Children’s binge eating disorder scale

- LGBTQ:

-

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer

References

Coelho JS, Suen J, Clark BA, Marshall SK, Geller J, Lam PY. Eating disorder diagnoses and symptom presentation in transgender youth: a scoping review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(11):107.

Diemer EW, Grant JD, Munn-Chernoff MA, Patterson DA, Duncan AE. Gender identity, sexual orientation, and eating-related pathology in a national sample of college students. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(2):144–9.

Simone M, Hazzard VM, Askew AJ, Tebbe EA, Lipson SK, Pisetsky EM. Variability in eating disorder risk and diagnosis in transgender and gender diverse college students. Ann Epidemiol. 2022;70:53–60.

Avila JT, Golden NH, Aye T. Eating disorder screening in transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(6):815–7.

Hartman-Munick SM, Silverstein S, Guss CE, Lopez E, Calzo JP, Gordon AR. Eating disorder screening and treatment experiences in transgender and gender diverse young adults. Eat Behav. 2021;41: 101517.

Linsenmeyer WR, Katz IM, Reed JL, Giedinghagen AM, Lewis CB, Garwood SK. Disordered eating, food insecurity, and weight status among transgender and gender nonbinary youth and young adults: a cross-sectional study using a nutrition screening protocol. LGBT Health. 2021;8(5):359–66.

Pham AH, Eadeh HM, Garrison MM, Ahrens KR. A Longitudinal Study on Disordered Eating in Transgender and Nonbinary Adolescents [published online ahead of print, 2022 Dec 30]. Acad Pediatr. 2022;S1876-2859(22)00639-8.

Nagata JM, McGuire FH, Lavender JM, et al. Appearance and performance-enhancing drugs and supplements, eating disorders, and muscle dysmorphia among gender minority people. Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55(5):678–87.

Ferrucci KA, Lapane KL, Jesdale BM. Prevalence of diagnosed eating disorders in US transgender adults and youth in insurance claims. Int J Eat Disord. 2022;55(6):801–9.

Schvey NA, Pearlman AT, Kelin DA, Murphy MA, Gray JC. Obesity and eating disorder disparities among sexual and gender minority youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(4):412–5.

Chamay-Weber C, Combescure C, Lanza L, et al. Screening obese adolescents for binge eating disorder in primary care: The adolescent binge eating scale. J Pediatr. 2017;185:68.e1-72.e1.

Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467–8.

Kutz AM, Marsh AG, Gunderson CG, Maguen S, Masheb RM. Eating disorder screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test characteristics of the SCOFF. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(3):885–93.

Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM. Initial validation of the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake disorder screen (NIAS): a measure of three restrictive eating patterns. Appetite. 2018;123:32–42.

Zickgraf HF, Garwood SK, Lewis CB, et al. Validation of the nine-item avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder screen among transgender and nonbinary youth and young adults. Transgend Health. 2021: published online ahead of print.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Body mass index (BMI). Reviewed June 3, 2022. Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/index.html

Browne MW. An overview of analytic rotation in exploratory factor analysis. Multivariate Behav Res. 2001;36(1):111–50.

Kaiser HF. The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:141–51.

Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):1–36.

Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 2009;6(1):1–55.

Kaiser HF. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika. 1974;39(1):31–6.

Bartlett MS. The effect of standardization on a Chi-square approximation in factor analysis. Biometrika. 1951;38(3–4):337–44.

Bartlett MS. A note on the multiplying factors for various chi square approximation. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1954;16(2):296–8.

Campbell K, Peebles R. Eating disorders in children and adolescents: state of the art review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):582–92.

Kornstein SG, Kunovac JL, Herman BK, Culpepper L. Recognizing binge-eating disorder in the clinical setting: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15r01905.

Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav. 1982;7(1):47–55.

Herman BK, Deal LS, DiBenedetti DB, Nelson L, Fehnel SE, Brown TM. Development of the 7-item binge-eating disorder screener (BEDS-7). Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15m01896.

Shapiro JR, Woolson SL, Hamer RM, Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Bulik CM. Evaluating binge eating disorder in children: development of the children’s binge eating disorder scale (C-BEDS). Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(1):82–9.

Barry DT, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Comparison of patients with bulimia nervosa, obese patients with binge eating disorder, and nonobese patients with binge eating disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(9):589–94.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors have no funding to report in relation to this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L., D.S., S.G., A.G., C.L. and G.S collaborated on the study design. W.L. and G.S. conducted the data collection. D.S. conducted the statistical analyses. W.L. and D.S. prepared a first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript, provided feedback, and agreed on the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of Washington University in St. Louis provided a waiver of consent given that the nutrition screening is the standard of care.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Linsenmeyer, W., Stiles, D., Garwood, S. et al. Validation of the adolescent binge eating disorder measure (ADO-BED) among transgender youth and young adults. J Eat Disord 11, 91 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00816-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-023-00816-w