Abstract

Background

Disordered eating behaviour (DEB) represents a significant morbidity among people with type-1 diabetes (T1D). Continuous-subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) improves glycemic control and psychological wellbeing in those with T1D. However, its relation to DEB remains obscure.

Objectives

To compare DEB among adolescents with T1D on CSII versus basal-bolus regimen and correlate it with body image, HbA1C and depression.

Methods

Sixty adolescents with T1D (30 on CSII and 30 on basal-bolus regimen), aged 12–17 years were studied focusing on diabetes-duration, insulin therapy, exercise, socioeconomic standard, hypoglycemic attacks/week and family history of psychiatric illness. Anthropometric measures, HbA1C, binge eating scale (BES), body image tool, patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) and the Mini-KID depression scale were assessed.

Results

Among the studied adolescents with T1D, six had DEB (10%), 14 had poor body-image perception (23.3%), 42 had moderate body-image perception (70%) and 22 had depression (36.7%). Adolescents with T1D on CSII had significantly lower BES (p = 0.022), Mini-KID depression (p = 0.001) and PHQ9 (p = 0.02) than those on basal-bolus regimen. BES was positively correlated to depression (p < 0.001), HbA1C (p = 0.013) and diabetes-duration (p = 0.009) and negatively correlated to body-image (p = 0.003).

Conclusion

DEB is a prevalent comorbidity among adolescents with T1D, with higher frequency in those on basal-bolus regimen than CSII.

Plain English summary

Disordered eating behaviour is a significant morbidity among people with type 1 diabetes. It is associated with poor metabolic control and diabetes related complications even when the full diagnostic criteria of an eating disorder are not met. There is conflicting data in the literature regarding the prevalence of disordered eating behaviour in type 1 diabetes. The current study found that disordered eating behaviour is prevalent among 10% of the studied adolescents with type 1 diabetes. It was found to be more severe and frequent among those on basal-bolus insulin regimen than those on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Moreover, it was correlated with depression, poor glycemic control, poor body image and long diabetes duration. Thus further studies are needed to verify the role of continuous glucose monitoring in the management of DEB among those with T1D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Highlights

-

Disordered eating behavior is a prevalent morbidity among adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

-

Binge eating scale is positively correlated with depression, HbA1C and diabetes duration and negatively correlated with body image.

-

Adolescents with type 1 diabetes on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion have significantly lower frequency and severity of disordered eating behaviors.

Introduction

Disordered eating behaviour (DEB) represents a significant comorbidity among people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) [1, 2]. It is associated with poor metabolic control and diabetic complications even when the full diagnostic criteria of an eating disorder are not met [3]. DEB typically begins during adolescence and early adulthood [4]. As in the general population, DEB in adolescents with T1D is associated with higher BMI z score, younger age, female gender and body image distortion. In addition, specific behaviours and attitudes related to diabetes, such as dietary restriction, counting carbohydrates and insulin injection impose an additional risk for DEB [5].

Multiple risk factors are associated with DEB in adolescents with T1D. This includes emotional factors and disrupted hunger and satiety balance. People with diabetes have higher levels of depression and anxiety than do people in the general population [6]. Depression is a known risk factor for DEB and body image distortion [7]. Hypoglycemia, a common symptom of uncontrolled diabetes disrupts self-feeding regulation, leading to increased hunger and loss of control over eating among adolescents with T1D [8].

Treatment modalities of T1D may also influence DEB. The use of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII) is rising among children and adolescents with T1D. Studies document the beneficial role of CSII on glycemic control, quality of life and psychological wellbeing [9]. However, data about the impact of CSII on DEB are scarce and contradictory. The use of CSII may either improve DEB or worsen it [10]. On one hand, CSII imposes more focus on food intake and carbohydrate counting. On the other hand, it gives better flexibility in meal timing and contents decreasing diabetes distress and negative affect related to feeding. People on basal-bolus regimen have more depressive symptoms than those on CSII. However the relation between DEB and affect in people on CSII compared to basal-bolus is unknown.

Conventional eating disorder therapies are less effective for people with T1D [7]. DEB persists in adolescents with T1D even when there is improvement in body image [11]. This highlights the importance of identifying the unique risk determinants for DEB among adolescents with T1D in order to develop effective interventional modalities for them.

Aim

The aim of this study is to compare DEB in adolescents with T1D on CSII versus basal-bolus regimen and to correlate it with body image, glycemic control, and depressive symptoms.

Methodology

Study design and setting

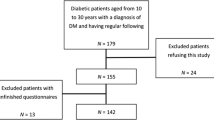

This cross sectional study included sixty adolescents with T1D recruited from the Pediatric Diabetes Clinic, Pediatric Hospital, Ain Shams University during the period from December 2020 to March 2021. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Ain Shams University, and an informed consent was obtained from each patient or their legal guardians before participation. Reporting of the study conforms to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 statement [12].

Patients' selection

Inclusion criteria included adolescents with T1D according to the International Society of Pediatric and Adolescents Diabetes (ISPAD) 2018 [13], aged 10–18 years on daily insulin therapy with CSII or basal-bolus regimen for at least 1 year. They were classified into two groups according to the mode of insulin administration. The selection for insulin therapy type (CSII or basal-bolus) was based on parental/patient factors including affordability/social class and patient/parent preference. Adolescents with comorbid conditions (i.e. celiac disease or autoimmune thyroiditis), other types of diabetes (i.e. maturity onset diabetes of youth [MODY] and type 2 diabetes mellitus) and those with history of psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Clinical assessment

All included adolescents were subjected to detailed medical history with special emphasis on disease duration, insulin daily dose (U/kg/day), exercise and the presence of clinically significant hypoglycemic episodes “i.e. glucose value of < 3.0 mmol/l (54 mg/dl)/week” [14]. The socioeconomic status was assessed using the validated Arabic socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. It is a scale with 7 domains with a total score of 84. According to the scale the socioeconomic level is classified into very low, low, middle and high levels depending on the quartiles of the score calculated [15].

Thorough clinical examination was done laying stress on anthropometric measures and body mass index (BMI) measured as kg/m2 with calculation of z score [16]. Peripheral blood samples were collected on potassium-ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (K2-EDTA) in sterile vacutainer tubes (final concentration of 1.5 mg/ml) (Beckton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for assessment of HbA1C.

Psychological assessment

Family history of psychiatric illness was assessed by self report due to the lack of registration files. The severity of depressive symptoms was assessed with the Arabic version [17] of the nine item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) [18]. This self report questionnaire includes the nine symptoms of the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive disorder. A score of 5–9 is considered mild, 10–14 is moderate, 15–19 is moderately severe and ≥ 20 is severe depression. PHQ-9 demonstrates acceptable reliability and is validated among diabetes patients [19]. Though initially developed as a depression screening tool for adults, recent studies have shown that it is a reliable and valid tool for detection of depression among adolescents [20, 21].

A validated Arabic version [22] of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID), depression module was used as diagnostic test for depression. The MINI-KID provides a structured interview for DSM IV and ICD-10 childhood and adolescent disorders [23].

For assessment of DEB, the binge eating scale (BES) Arabic version was used [24]. It is a 16-item self-reporting questionnaire designed to capture the behavioural, as well as the cognitive and emotional features of DEB in adults [25]. For each item, respondents are asked to select one of three or four response options, coded zero to two or three, respectively. Individuals’ scores are summed and ranged from 0 to 46, with higher scores indicating more severe binge eating problems. Clinical cut-off scores for the BES represent none-to-minimal (≤ 17 total score), moderate (18–26), and severe (> 27) binge eating problems. DEB was defined as having a BES score of > 17 [25]. The BES has been validated for use in children and adolescents [26].

The body image tool (an Arabic questionnaire that consists of a 34-item scale with scores between 1 [never] to 5 [always] for each item) was used for detection of body image distortion [27]. It measures the cognitive and behavioural symptoms associated with personal body dissatisfaction. A lower score less than 112 indicates more body dissatisfaction while higher score more than 140 indicates high self-body image satisfaction and between 112 and 140 scores indicates average body satisfaction [28].

Statistical analysis

Analysis of data was performed using software MedCalc v. 19. Data were explored for normality using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of normality. Quantitative data were presented as mean, standard deviations and ranges when their distribution was normally distributed and median with inter-quartile range (IQR) when their distribution was non parametric. Qualitative variables were presented as frequency and percentage. The comparison between groups with qualitative data was done by using Chi-square test when more than 20% of cells have expected frequencies ≥ 5 and with Fisher exact test when more than 20% of cells have expected frequencies < 5. Comparison between data with parametric distribution was done using independent t-test while for non-parametric data this was done by using the Mann–Whitney test. Binary correlation was carried out by Pearson correlation test. Results were expressed in the form of correlation coefficient (R) and p values. The correlation coefficient was interpreted as no linear relationship (0), a perfect positive linear relationship (+ 1) and a perfect negative linear relationship (− 1). Values between 0 and 0.3 or (0 and − 0.3) indicate no or a weak positive (negative) linear relationship. Values between 0.3 and 0.7 or (− 0.3 and − 0.7) indicate a moderate positive (negative) linear relationship. Values between 0.7 and 1.0 or (− 0.7 and − 1.0) indicate a strong positive (negative) linear relationship. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to assess predictors of DEB among the studied adolescents with T1D. The confidence interval was set to 95% and the margin of error accepted was set to 5%, so the p value was considered significant at a level of < 0.05.

Results

The mean age of the studied adolescents with T1D was 13.35 ± 3.28 years. They were 35 females (58.3%) and 25 males (41.7%). Their median BMI was − 0.08 (− 1.05 to 0.74) and their mean HbA1C was 8.49%, range 6.6–13.5.

DEB in adolescents with T1D

Six adolescents with T1D were found to have DEB (10%). The median BES of the studied adolescents with T1D was 7, range 0–22. Their median body image tool was 121.5, range 84–145, with fourteen having poor body image perception (23.3%), forty two having moderate body image perception (70%) and only four having good body image perception (6.7%). Twenty two adolescents with T1D had depression (36.7%).

DEB and CSII

None of the adolescents with DEB or poor body image perception was on the CSII regimen. Adolescents with T1D on CSII had significantly lower BES (p = 0.022), Mini-kid depression scale (p = 0.001) and PHQ9 (p = 0.02) with significantly higher socioeconomic status scale (p = 0.041) than those on basal-bolus regimen, Table 1.

DEB risk determinants

Upon comparing adolescent with T1D having DEB and those without, DEB was significantly lower in those on CSII (p = 0.009) than those on basal-bolus regimen. Moreover, it was positively related to family history of psychiatric disease (p = 0.008), smoking (p = 0.008), HbA1C (p = 0.038) and diabetes duration (p = 0.028), depression (p = 0.004) and poor body image (p = 0.003), Table 2. Although DEB was more prevalent in females, no significant relation was found between DEB and gender (p = 0.190). Notably, no significant relation was found between the socioeconomic status and DEB (p = 0.634) despite being significantly lower among those on CSII.

Correlations revealed that BES was positively correlated to PHQ9 (p < 0.001), HbA1C (p = 0.013) and diabetes duration (p = 0.009) and negatively correlated to body image (p = 0.003), Fig. 1.

Multi-variate logistic regression analysis for predictors of DEB revealed that it was most correlated to the disease duration (p = 0.037) and body image (p = 0.02), Table 3.

Discussion

Despite the prevalence and clinical significance of DEB in T1D, it remains understudied and effective treatment modalities are lacking. Adolescents with T1D are especially vulnerable to DEB, since both adolescence and diabetes impose risk factors for DEB [29]. Moreover, the co-occurrence of DEB and T1D dramatically increase the rates of morbidity and mortality [30]. Hence, understanding the risk determinants of DEB among adolescents with T1D is crucial to identify effective treatment modalities.

The prevalence of DEB in the studied cohort of adolescents with T1D was 10%. This prevalence is lower than previous Danish and Italian studies that found DEB in 21% and 21.8% of adolescents with T1D, respectively [31, 32]. Prevalence estimates for DEB are variable between different studies with a wide range from < 1 to 39% [33,34,35,36]. This discrepancy could be attributed to cultural differences, different study designs, timing and sample characteristics among the studied populations.

The association between T1D and DEB could be attributed to the presence of several risk factors for DEB in T1D, like lifelong insulin therapy, attendant weight gain, food preoccupation (e.g., carbohydrate counting), low self‐esteem, and depression [37]. Weight gain during puberty is exacerbated in adolescents with T1D on intensified insulin therapy which can lead to DEB [38].

Peterson and colleagues, 2018 hypothesized a modified dual pathway model to determine the risk factors of developing DEB in people with T1D. They hypothesized that diabetes duration, disruption to hunger and satiety secondary to exogenous insulin administration and fluctuations in blood glucose increase the risk for DEB in people with T1D [8]. The preceding goes in line with the current results where adolescents with T1D having DEB had significantly higher diabetes duration and HbA1C than those without DEB. Similarly, Nip and coworkers found that HbA1C was higher in youth with T1D with DEB than those without [5].

The effect of glycemic and insulin fluctuations on hunger and satiety was recently proven by Al-Zubaidi et al. who found that glycemic and insulin fluctuations in healthy normal weighed men were associated with changes in the brain hunger and satiety centers activity [39]. The poor metabolic control associated with DEB in people with T1D could explain their higher vulnerability to diabetic complications.

DEB among adolescents with T1D was significantly associated with higher depression scale, poor body image and family history of psychological disorders. Depression is a well-known risk factor of DEB in people with T1D as well as in the general population [40].

Interestingly, no significant relation was found between DEB among the studied adolescents with T1D and gender. However, this need to be further verified as they might be underpowered with only 25 males in the study. Research on DEB in T1D often targets female adolescents and young adults. So far, men have been underrepresented in the DEB literature. Recent research suggests that DEB is not as rare in men as it has been assumed [41]. In agreement with the current results, a study using a diabetes-specific DEB questionnaire found a similar rate of DEB in males and females with T1D [42].

Treatment modality for T1D might influence DEB in people with T1D. In the current study adolescents with T1D on CSII had significantly lower prevalence of DEB than those on basal-bolus regimen. Previous data about the relation between DEB and CSII are contradictory and mostly come from adult studies. A study by Markowitz et al. suggests that DEB improved following treatment with CSII [10]. Similarly, a retrospective pilot study by Pinhas-Hamiel and colleagues showed that DEB was less prevalent among adolescent females on CSII compared with those on basal-bolus regimen [43]. In agreement with these results, Sanlier and colleagues reported lower depression and eating disorders survey scores for those using CSII (n = 24) in a sample of 149 children and adolescents with T1D [44]. In contrast, Prinz et al. found no significant difference in the frequency of DEB between those on CSII and basal-bolus regimen. However, they found that the rate of CSII discontinuation tends to be higher among people with T1DM and co-morbid DEB [45]. The lower frequency of DEB in those on CSII might be attributed to the improved eating behaviour in those on CSII given the higher flexibility in one's diabetes management, the reduced daily insulin requirements leading to a less pronounced weight gain, the better affect and glycemic control compared with basal-bolus regimen.

One limitation of this study is its relatively small sample size; its cross-sectional nature and the lack of randomization to different treatments which undermines its ability to draw causal relations. Therefore, further studies are needed to identify the effect of CSII on DEB among adolescents with T1D.

In conclusion, DEB is a prevalent morbidity among adolescents with T1D. It is associated with depression, distorted body image and poor glycemic control. Adolescents with T1D on CSII have significantly lower frequency and severity of DEB. Thus, CSII could be a promising treatment modality for adolescents with T1D having DEB. Further larger longitudinal studies are needed to verify the practical utility of CSII and the role of continuous glucose monitoring in the management of DEB among those with T1D.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be available upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Corbett T, Smith J. Disordered eating and body image in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care Child Young People. 2020;9:DCCYP053.

Vila G, Robert JJ, Nollet-Clemencon C, Vera L, Crosnier H, Rault G, Jos J, Mouren-Simeoni M. Eating and emotional disorders in adolescent obese girls with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;4:270–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01980491.

Wisting L, Reas DL, Bang L, Skrivarhaug T, Dahl-Jørgensen K, Rø Ø. Eating patterns in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: associations with metabolic control, insulin omission, and eating disorder pathology. Appetite. 2017;114:226–31.

Hanlan ME, Griffith J, Patel N, Jasser SS. Eating disorders and disordered eating in type 1 diabetes: prevalence, screening, and treatment options. Curr Diabetes Rep. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-013-0418-4.

Nip A, Reboussin B, Dabelea D, Bellatorre A, Mayer-Davis E, Kahkoska A, Lawrence J, Peterson C, Dolan L, Pihoker C. Disordered eating behaviors in youth and young adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes receiving insulin therapy: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):859–66. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-2420.

Meadows A, Hyder S, Guenthner G, Pozzo A. 3.59 Pilot psychiatric screening for patients with type 1 diabetes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(10):S201.

Moskovich A, Dmitrieva N, Babyak M, Smith P, Honeycutt L, Mooney J, Merwin R. Real-time predictors and consequences of binge eating among adults with type 1 diabetes. J Eat Disord. 2019;7(7):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-019-0237-3.

Peterson CM, Young-Hyman D, Fischer S, Markowitz J, Muir A, Laffel L. Examination of psychosocial and physiological risk for bulimic symptoms in youth with type 1 diabetes transitioning to an insulin pump: a pilot study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43(1):83–93. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx084.

Mueller-Godeffroy E, Vonthein R, Ludwig-Seibold C, Heidtmann B, Boettcher C, Kramer M, Hessler N, Hilgard D, Lilienthal E, Ziegler A, Wagner V, German Working Group for Pediatric Pump Therapy (agip). Psychosocial benefits of insulin pump therapy in children with diabetes type 1 and their families: the pumpkin multicenter randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(8):1471–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12777. Erratum in: Pediatric Diabetes. 2020;21(1):144–5. PMID: 30302877.

Markowitz JT, Alleyn CA, Phillips R, Muir A, Young-Hyman A, Laffel A. Disordered eating behaviors in youth with type 1 diabetes: prospective pilot assessment following initiation of insulin pump therapy. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15(5):428–33. https://doi.org/10.1089/dia.2013.0008.

Troncone A, Cascella C, Chianese A, Galiero I, Zanfardino A, Confetto S, Perrone L, Iafusco D. Changes in body image and onset of disordered eating behaviors in youth with type 1 diabetes over a 5-year longitudinal follow-up. J Psychosom Res. 2018;109:44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.03.169.

Saint-Raymond A, Hill S, Martines J, Bahl R, Fontaine O, Bero L. Consort 2010. Lancet. 2010;376(9737):229–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61134-8.

Mayer-Davis EJ, Kahkoska AR, Jefferies C, Dabelea D, Balde N, Gong C, Aschner P, Craig M. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2018: definition, epidemiology, and classification of diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(27):7–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12773.

Abraham MB, Jones TW, Naranjo D, Karges B, Oduwole A, Tauschmann M, Maahs D. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2018: assessment and management of hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(27):178–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.12698.

El-Gilany A, El-Wehady A, El-Wasify M. Updating and validation of the socioeconomic status scale for health research in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(9):962–8.

World Health Organization. Department of Nutrition for Health and Development. WHO Child growth standards. Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height, and body mass index-for-age. Methods and development. Geneva: WHO; 2006. p. 301–4.

Belhadj R, Jomli H, Ouali U, Zgueb Y, Nacef F. Validation of the Tunisian version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9). Eur Psychiatry. 2017;41:S523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.695.

Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.

Van Steenbergen-weijenburg KM, Vroege L, De Ploeger R, Brals J, Vloedbeld M, van der Feltz-cornelis C, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Rutten F, Beekman A, van der Feltz-cornelis C. Validation of the PHQ-9 as a screening instrument for depression in diabetes patients in specialized outpatient clinics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):235. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-235.

Lewandowski R, O’Connor B, Bertagnolli A, Beck A, Beck A, Gardner W, Horwitz S, Newton D, Wain K, Boggs J, Brace N, deSa P, Scholle S, Hoagwood K, Horwitz S. Screening and diagnosis of depression in adolescents in a large HMO. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(6):636–41. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400465.

Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, McCarty C, Richards J, Russo J, Rockhill C. Evaluation of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1117–23. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0852.

Bishry A, Ghanem H, Sheehan S. Comparison of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children (MINI-KID) with the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school aged children—present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): in an Egyptian sample presenting with childhood disorders, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University [MD Thesis]. 2012; Egypt.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar G. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(20):22–57.

Zeidan RK, Haddad C, Hallit R, Akel M, Honein K, Akiki M, Kheir N, Hallit S, Obeid S. Validation of the Arabic version of the binge eating scale and correlates of binge eating disorder among a sample of the Lebanese population. J Eat Disord. 2019;7(40):1–14.

Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardon D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav. 1982;7(1):47–55.

Marcus M, Wing R, Hopkins J. Obese binge eaters: affect, cognitions, and response to behavioral weight control. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(3):433.

El Desoki M. Body image distortion questionnaire. Cairo: El-Anglo Egyptian Library; 2004.

El Desoki M. Eating disorder handbook, series of Arabic psychiatric disorders. Cairo: The Anglo Egyptian Bookshop; 2006.

Wisting L, Frøisland D, Skrivarhaug T, Dahl-Jørgensen K, Rø O. Disturbed eating behavior and omission of insulin in adolescents receiving intensified insulin treatment. A nationwide population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3382–7. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0431.

Keane S, Clarke M, Murphy M, McGrath D, Smith D, Farrelly N, MacHale S. Disordered eating behaviour in young adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Eat Disord. 2018;6(9):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-018-0194-2.

Nilsson F, Madsen J, Jensen A, Olsen B, Johannesen J. High prevalence of disordered eating behavior in Danish children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2020;21(6):1043–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/pedi.13043.

Pinna F, Diana E, Sanna L, Deiana V, Manchia M, Nicotra E, Fiorillo A, Albert U, Nivoli A, Volpe U, Atti AR, Ferrari S, Medda F, Atzeni MG, Manca D, Mascia E, Farci F, Ghiani M, Cau R, Tuveri M, Cossu E, Loy E, Mereu A, Mariotti S, Carpiniello B. Assessment of eating disorders with the diabetes eating problems survey—revised (DEPS-R) in a representative sample of insulin-treated diabetic patients: a validation study in Italy. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(262):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1434-8.

Jones JM, Lawson ML, Daneman D, Olmsted MP, Rodin GM. Eating disorders in adolescent females with and without type 1 diabetes: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2000;320(7249):1563–6.

Scheuing N, Bartus B, Berger G, Haberland H, Icks A, Knauth B, Nellen-Hellmuth N, Rosenbauer J, Teufel M, Holl R, on behalf of the DPV Initiative; the German BMBF Competence Network Diabetes Mellitus. Clinical characteristics and outcome of 467 patients with a clinically recognized eating disorder identified among 52,215 patients with type 1 diabetes: a Multicenter German/Austrian Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1581–9.

Reinehr T, Dieris B, Galler A, Teufel M, Berger G, Stachow R, Golembowski S, Ohlenschläger U, Holder M, Hummel M, Holl R, Prinz N. Worse metabolic control and dynamics of weight status in adolescent girls point to eating disorders in the first years after manifestation of type 1 diabetes mellitus: findings from the diabetes patienten verlaufsdokumentation registry. J Pediatr. 2019;207:205-212.e5.

Priesterroth L, Grammes J, Clauter M, Kubiak T. Diabetes technologies in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus and disordered eating: a systematic review on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, continuous glucose monitoring and automated insulin delivery. Diabet Med. 2021;38:e14581. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14581.

Troncone A, Chianese A, Zanfardino A, Cascella C, Piscopo A, Borriello A, Rollato S, Casaburo F, Testa V, Iafusco D. Disordered eating behaviors in youths with type 1 diabetes during COVID-19 lockdown: an exploratory study. J Eat Disord. 2020;8(76):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00353-w.

Toni G, Berioli M, Cerquiglini L, Ceccarini G, Grohmann U, Principi N, Esposito S. Eating disorders and disordered eating symptoms in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):906.

Al-Zubaidi A, Heldmann M, Mertins A, Brabant G, Nolde J, Jauch-Chara K, Münte T. Impact of hunger, satiety, and oral glucose on the association between insulin and resting-state human brain activity. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:162. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00162.

Sander J, Moessner M, Bauer S. Depression, anxiety and eating disorder-related impairment: moderators in female adolescents and young adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2779. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052779.

Murray SB, Nagata JM, Griffiths S, Calzo J, Brown T, Mitchisong D, Blashillhi A, Mond J. The enigma of male eating disorders: a critical review and synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;57:1–11.

Doyle E, Quinn S, Ambrosino J, Weyman K, Tamborlane W, Jastreboff A. Disordered eating behaviors in emerging adults with type 1 diabetes: a common problem for both men and women. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31(3):327–33.

Pinhas-Hamiel O, Graph-Barel C, Boyko V, Tzadok M, Lerner-Geva L, Reichman B. Long-term insulin pump treatment in girls with type 1 diabetes and eating disorders—is it feasible? Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12(11):873–8.

Sanlier N, Ağagündüz D, Ertaş Öztürk Y, Bozbulut R, Karaçil EM. Depression and eating disorders in children with type 1 diabetes. HK J Paediatr. 2019;24:16–24.

Prinz N, Bächle C, Becker M, Berger G, Galler A, Haberland H, Meusers M, Mirza J, Plener PL, von Sengbusch S, Thienelt M, Holl RW, DPV Initiative. Insulin pumps in type 1 diabetes with mental disorders: real-life clinical data indicate discrepancies to recommendations. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(1):34–8.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NYS: conceptualization, data collection, paper writing and submission. MAA: data collection and questionnaire performance. MSA: conceptualization, data collection and interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Ain Shams University with an approval number FMASU R 32/2021. An informed consent was obtained from each patient or their legal guardians before participation.

Consent for publication

All authors declare their consent for this article to be published in the Journal of Eating Disorders.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Salah, N.Y., Hashim, M.A. & Abdeen, M.S.E. Disordered eating behaviour in adolescents with type 1 diabetes on continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; relation to body image, depression and glycemic control. J Eat Disord 10, 46 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00571-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00571-4