Abstract

Background

Fine-scale data on animal position are increasingly enabling us to understand the details of animal movement ecology and dead-reckoning, a technique integrating motion sensor-derived information on heading and speed, can be used to reconstruct fine-scale movement paths at sub-second resolution, irrespective of the environment. On its own however, the dead-reckoning process is prone to cumulative errors, so that position estimates quickly become uncoupled from true location. Periodic ground-truthing with aligned location data (e.g., from global positioning technology) can correct for this drift between Verified Positions (VPs). We present step-by-step instructions for implementing Verified Position Correction (VPC) dead-reckoning in R using the tilt-compensated compass method, accompanied by the mathematical protocols underlying the code and improvements and extensions of this technique to reduce the trade-off between VPC rate and dead-reckoning accuracy. These protocols are all built into a user-friendly, fully annotated VPC dead-reckoning R function; Gundog.Tracks, with multi-functionality to reconstruct animal movement paths across terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial systems, provided within the Additional file 4 as well as online (GitHub).

Results

The Gundog.Tracks function is demonstrated on three contrasting model species (the African lion Panthera leo, the Magellanic penguin Spheniscus magellanicus, and the Imperial cormorant Leucocarbo atriceps) moving on land, in water and in air. We show the effect of uncorrected errors in speed estimations, heading inaccuracies and infrequent VPC rate and demonstrate how these issues can be addressed.

Conclusions

The function provided will allow anyone familiar with R to dead-reckon animal tracks readily and accurately, as the key complex issues are dealt with by Gundog.Tracks. This will help the community to consider and implement a valuable, but often overlooked method of reconstructing high-resolution animal movement paths across diverse species and systems without requiring a bespoke application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Reconstructing animal movement paths is an important tool in ecology, providing insights into animal space-use, behaviour and habitat selection [1,2,3]. However, accurate estimation of paths at fine temporal scales has proved a persistent challenge [4, 5]. Dead-reckoning is a method used to reconstruct animal movement paths, based on sequentially integrating the vector of travel from a predetermined position using estimates of heading (also termed ‘bearing’ or ‘yaw’) and speed (and displacement about the vertical axis for 3-D movements), over an elapsed time interval [6,7,8,9]. In its most advanced form, it can provide positional data with sub-second resolution, irrespective of the environment [e.g., 10, 11, 12] and it therefore has huge potential for providing data that can elucidate many fundamental behavioural and ecological issues related to space-use.

The concept of dead-reckoning (also termed ‘track integration’) originated to aid nautical navigation [6, 13], though its utility to reconstruct uninterrupted fine-scale (in time and space) animal movement paths by integrating different sensors in animal-attached tags was suggested over three decades ago [14, 15]. Today, this typically involves the simultaneous deployment of tri-axial accelerometers and magnetometers [e.g., 9, 10, 16, 17–20], utilising the tilt-compensated compass method [21,22,23,24] (see “Glossary” for a definition of dead-reckoning-related terminology used throughout).

The utility of dead-reckoning depends on the accuracy of speed and heading estimates (see Table 1) and, due to the nature of vector integration, dead-reckoned tracks accumulate errors (commonly termed ‘drift’) over time [15, 25, 26]. As a result, periodic ground-truthing by a secondary source is important for maintaining the accuracy of animal paths with all its underlying scales and tortuosity of movement [9, 10, 27]. For this reason, dead-reckoning data are normally enhanced by combining it with other methods for providing Verified Positions (VPs). These are primarily; direct observation [e.g., 28], light intensity-based geolocation [e.g., 29], VHF—[e.g., 30], acoustic—[e.g., 31] and GPS telemetry [e.g., 26]. Other, less utilised, systems that may also have merit at sites frequented by the tagged animals, include radio frequency identification (RFID) stations [cf. 32], camera traps [cf. 33] and video footage, such as closed-circuit television (CCTV) surveillance [e.g., 34]. Although all these systems are subject to a number of issues that can make their positional fixes temporally widely spaced [e.g., 4, 35, 36], inaccurate [e.g., 37, 38, 39] or impossible [e.g., 40, 41, 42], they can be critical in providing ground-truthed positions, even infrequently, with which to reset accumulated drift [9, 26].

Of the above VP options, GPS-corrected dead-reckoning is the most widely used and there is a marked bias towards marine studies [e.g., 10–12, 15–17, 19, 27, 43, 44–56]. This is likely for logistical reasons, with many aquatic animals being larger (and thus can carry larger/more devices) than their terrestrial counterparts [57], whilst the utility of transmission telemetry is restricted to periodic resurfacing events [58]. Moreover, speed can be more easily measured or approximated in water, with previous studies obtaining estimates via acoustic flow noise [e.g., 59], passive sonar [e.g., 60], pitch and change in depth [e.g., 11] and speed sensors [cf. 16, 61, 62]. The efficacy of such techniques diminishes within the aerial environment, principally, due to the marked difference between water and air density [cf. 63] and the current speed and volatility of wind [cf. 64, 65]. Indeed, this may explain why, in part (to our knowledge), only one study to date has dead-reckoned a volant species [66]. More recently, dynamic body acceleration (DBA, see Wilson et al. [67], for recent review) has been validated as a proxy of speed for terrestrial animals [68, 69] although there are still very few studies that use the dead-reckoning method in terrestrial animals [e.g., 9, 10, 26, 34, 70, 71].

We suggest that another reason that Verified Position Correction (VPC) dead-reckoning has been little used relates to the apparent difficulty and poor accessibility of the analytical processes involved. With this in mind, the primary aim of this paper is to provide potential users with a clear, concise roadmap for implementing dead-reckoning protocols. Specifically, we revisit the dead-reckoning methodology, from calibrating magnetometry data and deriving heading (tilt-compensated compass method), to VPC dead-reckoning within both terrestrial and fluid media. We provide simplistic conceptual explanations and mathematical protocols and describe the pitfalls within the procedure that can increase error. We also translate the relevant equations into complementary R code [cf. 93, available at 94] throughout the text, with fully annotated scripts deposited in Additional files 2, 3, 4, 5 and GitHub [available at 95].

In addition to the above, we outline recent advances to the VPC dead-reckoning technique. For use in terrestrial environments, this includes implementing step counts as a distance measure, by-passing dynamic body acceleration (DBA) as a proxy of speed, and assessing the value of ‘reverse dead-reckoning’ (useful when VPs are concentrated to the latter end of an animal’s trajectory). For marine and aerial environments, we demonstrate the value of integrating tidal-/air current data with dead-reckoned vectors (hereafter termed ‘current integration’) to reduce errors attributed to drift [cf. 46, 92]. Across all three media of travel (land, water and air), we show the value of incorporating different speed coefficients according to behaviour types. In addition, we provide examples of the various methods by which VP data can be under-sampled (relevant for high-res GPS datasets) prior to correcting dead-reckoned tracks and discuss the scales at which users should consider VP correction (which depend on the details of species-specific movement and length of data acquisition). We specifically demonstrate the above using our R-functions (Gundog.Tracks being the primary function for dead-reckoning), providing examples of its utility across various scenarios. Lastly, we highlight the relevance of heading and distance correction factors (derived from the VPC procedure), which can also be used to interrogate the animal–environment interaction and biases stemming from animal tag performance.

To illustrate our approach, we use three model species (the African lion Panthera leo, the Magellanic penguin Spheniscus magellanicus and the Imperial cormorant Leucocarbo atriceps) that cover almost two orders of size magnitude in body mass and that operate in markedly different environments and at different scales of movement. To make this review more broadly applicable to researchers of varying dead-reckoning and R knowledge, we have departed from a traditional article format and instead, split this body of work into two distinct sections: firstly, we provide an overview of the critical Gundog.Tracks function and provide a brief review of the conceptual workflow (“Implementation of Gundog.Tracks” section). With respect to this, we discuss the relevant strengths and limitations of the current dead-reckoning framework and the key considerations involved. Secondly, we detail each ‘potential’ stage of the VPC dead-reckoning procedure with exemplar mathematical equations and R syntax (“VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section).

Implementation of Gundog.Tracks

We expand on key concepts in Additional file 1 and provide complimentary R scripts (outlined below) in Additional files 2, 3, 4 and 5. We also supply an example data set of a Magellanic penguin walking out to sea in Additional file 6, which can be used to trial each of the provided R scripts and perform the full dead-reckoning process. Mathematical equations are referred to as ‘Eqs. 1–33’ and R syntax as ‘Rx’, where ‘x’ is the reference number. To simplify concepts, we use base R syntax (wherever possible) and typically use vectors to demonstrate points made, though ‘df$’ directly before the variable name indexes data retained within data frame columns (assuming data frame is called ‘df’). We note, however, that more efficient code implementations are possible (e.g., data.table [96] and lapply()) than presented here, especially for large data, but here wanted to make the code as readable as possible in this manuscript, especially to persons not familiar with complex coding. More efficient code will be implemented through updated GitHub versions of the functions. See Additional file 1: Text S1 for our model species’ device setup and capture protocol and the glossary for a definition of dead-reckoning related terminology.

User functionality

Gundog.Tracks is an all-encompassing dead-reckoning function that can be used to dead-reckon animal paths travelling terrestrially or through fluid media. Table 2 details all the function’s input requirements/options.

Reverse dead-reckoning

Dead-reckoning backwards is useful when the start position is unknown, but the finishing coordinates are known. For example, central-place foraging, diving animals returning to land from the sea may not acquire a satellite fix for an appreciable period of time following submersion in water which can make determining the start position difficult. So, when VPs are skewed to the latter part of the track, it may be beneficial to start the iterative dead-reckoning process from that end. This involves reversing the order of data to be dead-reckoned and changing heading values by 180 degrees prior to dead-reckoning.

Integrating current vectors

Wind or ocean currents can change the relationship between an animal’s (longitudinal axis) bearing and speed of travel from their true vector of travel [46, 92]. This drift can be incorporated within movement paths by advancing each iterated dead-reckoned vector according to the direction and speed of the current at that point in space and time (cf. Fig. 1).

Schematic representation of a current flow vector (orange) (due to its speed and direction) being integrated to a given travel vector (blue). The x, y reflect the initial location of a dead-reckoned track, x2 and y2 are the resultant location following the integration of a travel vector (prior to current integration) and xxx and yyy advance these x 2 and y2 values a step further in the direction of the current flow vector. The dashed lines indicate the magnitude of the x and y dimensions of travel (both pre- and post-current flow integration) and the green line reflects the actual travel vector

DBA–speed derivation

Given the approximate linear relationship between DBA [sensu 67] and terrestrial animal speed [speed = (DBA·m) + c], DBA estimates can be multiplied by a gradient, m (the multiplicative coefficient) and summed with an intercept, c (the constant) to derive speed [10, 26]. These values are typically substituted with results from DBA–speed linear regression estimates, such as from treadmill tests or using GPS-derived speed [26, 69, 97, 98]. The m-coefficient should be selected such that (uncorrected) dead-reckoned tracks accord with the apparent straight-line distance between VPs. Importantly, the DBA–speed relationship may be a function of terrain-type (e.g., sand vs. concrete), animal state (e.g., weight variation) and mode of movement (e.g., running vs. climbing) [cf. 68]. For instance, a condor gliding within a thermal would have high speeds, despite having negligible DBA, while an Ibex traversing across different substrate types and gradients would impart varying magnitudes of acceleration that may scale non-linearly with a change in stride gait. It may be of value, therefore, to iteratively change the supplied m (and possibly c) values between VPs according to behaviour and environment. The user may also opt to supply a ‘marked events’ (ME) vector (a marked event is a term we use that refers to a number of sequential (in time) data points within a dataset coded by integer values) to ensure dead-reckoned tracks are not advanced with non-animal movement behaviours. Within Gundog.Tracks, ME values of one or greater reflect progressive movement, and zero values code for stationary behaviour—dead-reckoned tracks are not advanced when ME = 0 (irrespective of the allocated speed). For example, in its simplest form, ME could be filled with binary 0 s and 1 s as governed by a DBA threshold (labelling the ME vector 0 in sleep and resting behaviour).

Pre-determining speed

For terrestrial species (specifically bipeds and quadrupeds), the interplay between peak heave acceleration amplitude and periodicity may be a useful indicator for the movement gait adopted [99], which may help decide the m-coefficient in the DBA–speed relationship [69]. There may be times, however, when DBA is an unreliable proxy of terrestrial speed [cf. 68]. At this time, given that the stride cycle can be easily detected by cyclic peaks in a given acceleration channel [e.g., 100, 101, 102], peak periodicity (and amplitude) may be used as a proxy of distance moved by providing a distance per step estimate (assuming constant distance travelled between step gaits if only concerning step periodicity—cf. “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section and Additional file 1: Text S4).

DBA is a weak proxy of speed for many marine animals because overall body tissue density changes with depth when air is associated so that speed may be invariant of the movement kinematics [cf. 103, 104]. DBA is also a weak proxy for flying animals that glide at constant velocity, use thermals or bank [cf. 105]. One of the most common methods for determining animal speed in water is via devices that estimate flow or resistance rate [16, 19, 64, 106]. These often have appreciable limitations, with currents, biofouling, blockage and turbulence affecting performance [64], and many of these issues are applicable to volant species, so that bird speed measures are typically restricted to GPS-derived estimates of ground speed [cf. 107]. In the absence of a reliable motion sensor-derived speed proxy, previous reported approximated speed estimates according to movement modes and/or topological whereabouts can be used [cf. 30]. For example, for various diving animals such as penguins, a simple depth threshold may prove effective to differentiate between various previous reported modal ‘surface-resting’ and ‘underwater-commuting’ speeds [61, 108,109,110]. For volant species, whilst wingbeat frequency or amplitude does not scale reliably with air speed [cf. 111], the interplay between both can decipher various flight modes (e.g., ‘cruising speed’ vs taking off/landing) [65, 112]. Furthermore, tail beat frequency has been shown to be a good predictor of swimming speed for various fish species [113,114,115]. For diving animals, a proxy for horizontal speed can be obtained based on animal pitch and rate of change of depth [11, 116]. Specifically, the rate change of depth is divided by the tangent of the body pitch.

In any case, when high-resolution VP data are available (e.g., 0.01–10 Hz GPS), for instance, during short-term trial deployments, speed estimates can be compared alongside those derived between VPs and approximated according to behaviour type (elucidated from, for example, accelerometer—[e.g., 117, 118], magnetometry—[e.g., 105, 119], depth- [e.g., 120] or altitude—[e.g., 65] data), and uncorrected dead-reckoned tracks can be compared alongside VPs to determine where biases may occur visually. Furthermore, the correction factors obtained from the VPC process are viable comparators for detecting consistent under- or over-estimations of speed and/or heading offsets (e.g., due to tag placement). Essentially, when empirical speed evidence is unavailable, the user can ad hoc iteratively adjust allocated speed values or the underlying DBA–speed coefficients until uncorrected dead-reckoned track segments scale proportionately to their aligned ground-truthed positions (pre-VPC). Within Gundog.Tracks, the user can modulate m, c and ME values to switch between predetermined speed (m = 1, c = 0), DBA-derived speed (m > 0, c ≥ 0) and stationary behaviour (ME = 0).

VPC procedure

Ground-truthing dead-reckoned tracks typically involves the linear drift correction method [cf. 26, 46], outlined in Constandache et al. [121] and Symington and Trigoni [122]. In essence, a shift vector aligns the starting dead-reckoned path segment with the VP at time point one, after which the difference between the VP and dead-reckoned path segment at time point two is calculated to provide a correction vector that is applied linearly between time point one and time point two. Our method follows the protocols outlined by Walker et al. [9], whereby the underlying correction coefficients (hereafter termed ‘factors’) for both heading and (radial) distance are calculated—adjusting the length and heading at each dead-reckoned path segment until the end points align to each VP along the path. This process requires the trigonometric ‘as the crow flies’ Haversine formulae [123,124,125] which allows one to translate a distance across the curvature of the Earth’s surface (detailed within “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section). The advantage of this method is that, whilst correction factors are constant between VPs, it does not assume that the dead-reckoned path deviates linearly over time from the true path because (radial) distance is multiplied by the distance correction factor. This ensures that parts of track where the animal is determined to be stationary (e.g., ME = 0) are left unaltered. The function’s method of VPC, automatically handles NaN and Infinite (Inf) values which can arise during the derivation of the distance correction factors (when no dead-reckoned movement occurs between successive VPs—detailed within “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section). It is worth noting that even animals that travel in 3-D can be subject to the 2-D dead-reckoning formulae and Haversine computation of distance correction factors because we typically assume that both dead-reckoned- and VP positions are aligned in vertical space (assuming reliable pressure—[60]/depth [13] data) and attempt to control for the horizontal component of speed [e.g., “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section—Eqs. (25, 27)] pre-correction. Although not covered here, we acknowledge that various state–space modelling techniques have also been developed to georeference dead-reckoned tracks [e.g., 11, 47].

Default inputs for calculations and outputs

Gundog.Tracks default input takes the form:

Gundog.Tracks(TS, h, v, elv = 0, p = NULL, cs = NULL, ch = NULL, m = 1, c = 0, ME = 1, lo = 0, la = 0, VP.lon = NULL, VP.lat = NULL, VP.ME = FALSE, method = NULL, thresh = 1, dist.step = 1, bound = TRUE, Outgoing = TRUE, plot = FALSE),

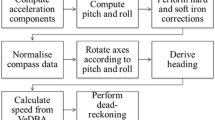

with input modulated according to the animal in question and data available (see Fig. 2).

Schematic of the conceptual workflow involved when dead-reckoning using Gundog.Tracks—elaborated within “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section. Note Gundog.Peaks (Additional file 3) is a peak finder function that locates peaks based on local signal maxima and Gundog.Compass (Additional file 2) is a function to correct iron distortions from tri-axial magnetometry data and subsequently compute tilt-compensated heading. Both functions are elaborated within “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section and in Additional file 1. The direction of workflow and key questions asked follow from green—(pre-processing and data alignment) to purple—(computing heading) sections, before splitting into blue—(air/water) and brown—(land) sections (computing speed) and culminating at the red section (final pre-dead reckoning checks/data formats and post-dead-reckoning checks/plots) in conjunction with the process of using Gundog.Tracks in R (yellow)

The function outputs a data frame containing various descriptive columns which, depending on the input, includes (but is not limited to):

-

The correction factors used

-

Heading and radial distance estimates (both pre- and post-current integration and/or VPC)

-

Distance moved and speed estimates (both in 2-D and 3-D when elevation/depth data supplied)

-

Net error between dead-reckoned positions and VPs (both pre- and post-correction)

-

Various VP summaries including notation of when VPs are present and which fixes were used in the correction process.

When specified, 2-D summary plots demonstrating the relationship between dead-reckoned positions and VPs (both pre- and post-current integration and/or VPC) are provided (e.g., Fig. 3). Table 3 details all the function’s available outputs (modulated according to input). Gundog.Tracks uses the na.locf() function from the ‘zoo’ package [126] and the slice() function from the ‘dplyr’ package [127] (both are checked as dependencies and installed when required within this function). Output 2-D distance/speed estimates are calculated with the Haversine formula. When depth/elevation data are supplied (and changes between sets of coordinates) 3-D distance/speed estimates are calculated with a variant of the Euclidean Formula—converting x, y, z from polar to Cartesian coordinates, and incorporating the Earth’s oblate spheroid [cf. World Geodetic System (WGS84)], via conversion from Geodetic- to Geocentric-latitude [cf. 128].

Dead-reckoned (DR) movement path of lion as provided by Gundog.Tracks summary plots (within the initialised R graphics window). This is an approximate 2-week trajectory over an approximated total travel (DR) distance of > 142 km. (Pre-filtered) GPS (red) was sampled at 1 Hz and derived heading and speed measurements were sub-sampled to 1 Hz (initial acceleration/magnetometry data were recorded at 40 Hz). The VPC dead-reckoned track (blue) was constructed using DBA–GPS-derived speed regression estimates and corrected approx. every 6 h. Note, for dead-reckoning within fluid media, an additional green dead-reckoned track with current integration and its associated distance estimates are also plotted (pre-correction) when wind/ocean currents are supplied (cf. Fig. 6). Accumulated 3-D DR distance is shown when elevation/depth data are supplied

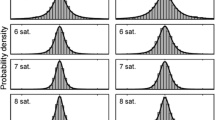

The interplay between numerical precision in R, correction rate and net error can make more than one round of adjustment necessary for dead-reckoning fixes to accord exactly with ground-truthed locations (cf. Fig. 4a), particularly given that slight discrepancies accumulate over time. Each iteration of the correction process produces a tighter adherence between estimated and ground-truthed positions [cf. 9]. Typically, this does not involve more than two rounds of VPC to achieve a maximum net error of 0.01 m (the threshold used within Gundog.Tracks) across a ca. (1 Hz) 2-week-long track. For an indication of processing times see Additional file 1: Text S6, Fig. S4; for example dead-reckoning a lion at 1 Hz for 7 (continuous) days (with plot = TRUE, dist.step = 5, VP.ME = TRUE, method = “time” and thresh = 3600) took 25 s to compute (on a MSI GP72 7RD Leopard laptop with intel core i7 processor). Logically, the net error between VPs and (corrected) dead-reckoned positions is positively correlated to the time between corrections (cf. Fig. 4b) [cf. 46], although the rate of net error ‘drop-off’ is dependent on the accuracy of the initial (uncorrected) dead-reckoned track (cf. Fig. 5), itself, modulated by the extent of system errors (Table 1) and initial user-defined track scaling.

Net error between (GPS-corrected) dead-reckoned and GPS positions for a track from 5 African lions. a Maximum net error (m) between ground-truthed GPS and time-matched dead-reckoned positions after one iteration of correction, both as a function of GPS correction rate [one correction per 1—(red), 12—(green) and 24—(blue) hours] and underlying m-coefficient used to determine the DBA-derived speed. Data from 5 lions (individual denoted by symbol shape) over a period of 12 days. Note that the difference in error varies according to individual, initial speed estimate and the rate of correction. b Net error between dead-reckoned positions and all available GPS fixes, according to correction rate (data from the same 5 lions), subsequent to the iterative procedure of GPS correction (maximum distance between GPS fix used in correction procedure and according dead-reckoned position < 0.01 m). Boxes denote the median and 25–75% interquartile range with a blue ‘loess’ smooth line. Whiskers extend to 1.5 * interquartile range in both directions

Dead-reckoned lion track in relation to GPS positions [a uncorrected and b corrected—approx. every 30 min (black circles)]. The start of the track (lo and la) is denoted with a black x. Three corresponding sections of each track are denoted with the same number and the finishing positions denoted with a circle (coloured according to its reference track). Note that the horizontal straight-line sections (cf. yellow arrow) result from the lion following the Botswana boundary fence (which this individual eventually crossed). Mean net error between (corrected) dead-reckoned positions and all available GPS fixes was higher for tracks resolved using a VeDBA threshold (0.11 g), than for tracks advanced only at times of depicted movement using the MVF method

Within this process, people assume VPs to be perfect, however, across all VP determining methods, the rate and accuracy of data acquisition is highly moderated according to the permissiveness of the environment, such as high-density shrub or submersion in water [e.g., 38, 129, 130]. GPS technology is arguably the most popular and widely used method for determining estimates of free-ranging animal movement [cf. 131, 132, 133]. This is because inspection of data is less complex and time-consuming than some of the alternatives, whilst improvements in design and battery longevity have enabled GPS units to be attached to a plethora of animals (up to almost four orders of magnitude in size and mass [cf. 11, 134]) and record at high frequencies (e.g., ≥ 1 Hz [131, 135]). Consequently, GPS units are unparalleled for providing such detailed quantification of space-use outside of the VPC dead-reckoning framework, and are the most utilised VPC method within (including the case study datasets within this study). However, locational accuracy (excepting precision error radius [cf. 136] and variable latency [cf. 137]) can vary by a few metres or be appreciably more depending upon the propagation of signal quality and/or receiver reception capability [38, 138, 139]. As such, VP error becomes more relevant at smaller scales of assessed movement and this is the reason why VP distance-moved estimates can go from being typically underestimated at low frequencies (due to linear interpolation of tortuous movements) [26, 140, 141] to overestimated at high frequencies [97, 136] and result in highly variable correction factors within the VPC dead-reckoning process [cf. 10]. Indeed, judicious selection of VPC rate is critical in maximising dead-reckoned track accuracy when relocation data are taken at fine spatial- and temporal resolutions [26] (cf. Table 2—‘VP.ME’, ‘method’, ‘thresh’ and ‘dist.step’ inputs to aid in modulating VPC rate). Likewise, the initial screening for location anomalies, across all VP methods and sampling intervals, is important so as to prevent incorrect distortion of tracks. Put simply, the higher the quality of VP data input, the greater the robustness of the VPC dead-reckoning output.

It was suggested by Bidder et al. [10], that the next stage in this work is to derive a standardised set of rules to maximise the value of both GPS (though this applies to any VP method) and dead-reckoned data in line with the questions being asked. We argue that consistent trends in the magnitude and/or bias of correction factors can be used as a diagnostic tool for elucidating: (i) VP inaccuracy (e.g., possibly manifested by extremely high distance and heading correction factors), (ii) required alterations to the DBA–speed relationship [e.g., due to traversing across different substrates (e.g., Fig. 5)] and (iii) drift due to current vectors [cf. 16, 46] (e.g., Fig. 6).

One Magellanic penguin’s dead-reckoned foraging trip at sea, lasting approximately 9 h (yellow arrow denotes the trajectory direction over time. Black track = GPS. Fifteen corrections (black circles) were made (method = “divide”). For comparison, the grey dotted track is the GPS-corrected dead-reckoned track with current integration approx. every 1 min (where possible-method = “time”) (a). Note the difference of net error between dead-reckoned positions and all available GPS fixes across the various tracks [insert = grey track] (b). Both uncorrected and corrected dead-reckoned tracks had less error after current integration (black arrows vector every 5 min) and this was reflected in the direction and magnitude of heading correction factors required per unit time (c). Heading correction factors obtained from the track corrected approx. every 1 min; the colour of the scale bar indicates the extent of the heading correction factor required)

The case-studies

An important question to address is how often to do VP correction. This is obviously dependent upon the scales of movement elicited and the medium in/on which the animal in question navigates. Put simply, one should VP correct as little as possible, but as much as is necessary and we elaborate on this using our model species operating in different media. Within Fig. 5, the 1 Hz GPS track (blue) is plotted alongside two different dead-reckoned tracks; [(a) = uncorrected and (b) = corrected approx. every 30 min (method = “time”)] from 12 days of data acquisition of one lion. There were two variations in the method of scaling the dead-reckoned tracks; a track based on a Vectorial Dynamic Body Acceleration (VeDBA) threshold (red), and a track advanced based on periods of identified movement (purple). The m-coefficient and c-constant values were determined from the VeDBA–GPS speed relationship (Fig. 5, inset a1) and the Movement Verified Filtering (MVF) protocol outlined by Gunner et al. [97] was used to depict movement and anomalous GPS fixes (green) and to compute reasonable GPS-derived speed estimates. This case study demonstrates three important points. Firstly, on its own, dead-reckoning is subject to substantial drift and so VPC is essential for resetting this error. The more frequent a user corrects, the more accurate the dead-reckon track becomes (relative to VPs), though VP error can also be substantial, especially during rest behaviour (see Gunner et al. [97] for demonstration of this). For collared animals, heading measurements can become inaccurate at times of erratic collar roll (cf. Table 1) and conjointly, GPS performance is also reduced when antenna position becomes compromised [e.g., 142].

Secondly, and in conjunction to the above, irrespective of VPC rate, the initial allocation of speed is important. Here, only dead-reckoning identified movement periods resulted in greater accuracy than just advancing tracks based on a VeDBA threshold. This is because even stationary behaviours can impart appreciable DBA [e.g., 143] (beyond the threshold), and thus wrongly advance tracks. The false patterns of tortuosity created from this, whilst scaled and possibly rotated with VPC (cf. “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section), remain incorporated to some degree. Whilst not illustrated here, advancing tracks without a VeDBA threshold would incur greater error still. Lastly, in this section, the distance correction factor was consistently high (Fig. 5, inset b1) as the lion travelled along the Botswana fence boundary, perhaps as a result of the animal walking on the compact dirt road at this location (Fig. 5, inset a2), altering the VeDBA–speed relationship. Such patterns in correction factors (whether consistent or highly variable) can highlight issues with the underlying track scaling.

Where animals move in water or air, obtaining accurate estimates of speed is more difficult without the use of speed sensors. Naturally, the resolution and accuracy of initial dead-reckoning track scaling (pre-VPC) reduces when speed has to be approximated using constant values according to behaviour type (a strategy used here). There is a balance between initial dead-reckoning accuracy and required VPC. The lower the initial track accuracy, the more frequent it should be corrected, and additional drift caused by external-force vectors compounds this issue. Within Fig. 6, we illustrate the value that current correction, dependent on current information, brings to the VPC procedure if the derived track is to be superimposed on the environment. Here, one Magellanic penguin was dead-reckoned with and without tidal vector integration (instantaneous tidal currents were deduced from a 3-D numerical model validated in the region [144], at hourly, 1 km2 grid nodes). Commuting speed was allocated 2.1 m/s [cf. 61, 145] and changed according to “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section—R41. Surface period ‘rest’ speed were allocated 0.416 m/s [cf. 108]. VP accuracy improved considerably both pre- and post- VPC when currents were integrated which points to the value of acquiring current data if possible, particularly if VPs are sparse. Notably the combination of dead-reckoning and VP estimation of both movements relative to the ground and fluid, may detail specific orientation strategies used and thus can have value for assessing the ability of drift compensation in aquatic or volant animals [46, 92]

For all our case study animals, GPS units were set to record at 1 Hz. With this temporal resolution (which is not always possible anyway due to the high-power requirements of the GPS), the value of dead-reckoning would seem questionable. However, dead-reckoning can: (i) work when GPS cannot—such as when an animal is underwater [e.g., 18] or in thick forest [cf. 2] and it can (ii) by-pass the issues arising from GPS inaccuracies such as ‘jitter’ [cf. 97], allowing for more accurate and finer scale delineations of movement. This is illustrated in Fig. 7, in which 12 outgoing (green) and incoming (blue) dead-reckoned trajectories from Magellanic penguins walking to and from their nest are plotted. Incoming tracks were reverse-dead-reckoned (Outgoing = FALSE, bound = FALSE), because the GPS did not always register fixes for minutes after birds left the water and because nest coordinates were known (Fig. 7, inset). This explains why the blue tracks extend into the sea rather than encroach further inland when speed was overestimated. What is evident is that even ‘accurate’ GPS paths are coarsely resolved due to precision errors. Indeed, even with little or no GPS error, this can greatly compromise movement estimates [cf. 136]. Conversely, the precision of the dead-reckoned tracks is only limited by the amount of initial motion sensor data under-sampling (usually required in some capacity to make datasets more manageable and less computationally expensive). Such fine-scale estimates can therefore (with suitable VPC) allow users to define movement in space with unprecedented resolution. The benefit of this is that such resolution can resolve important metrics of movement, such as step duration [cf. 146] and the number and extent of turns made [cf. 147]; useful parameters for investigating navigation and foraging strategies according to environmental circumstance—though, such parameters are also useful without superimposing on the environment. Moreover, even dead-reckoned tracks that are sparsely corrected or never corrected can detail important movement-specific behaviours [12], for example, circling behaviour [148].

Twelve outgoing (green) and incoming (blue) dead-reckoned trajectories from Magellanic penguins walking to and from their nest. Three variants of track advancement were used: a A VeDBA threshold (0.1 g) and constant m-coefficient (1.4) (b), depicted movement periods using the LoCoD method to identify steps (cf. Wilson et al. 2018) and constant m-coefficient (1.4) and c depicted individual steps within depicted movement periods, from which a constant distance estimate (0.16 m) was multiplied by step frequency (x̄ no. steps/s) (full details within Additional file 1: Text S4) (c). Note that the accuracy with respect to the radial distance can be evaluated by examining the track stops in relation to the shore-line. DBA-derived speed estimates were typically overestimated for incoming tracks, due to the birds being heavier (and thus impart greater DBA per stide cycle) after foraing. Tracks (from c) were GPS-corrected (d) (method = “distance”, dist.step = 5, VP.ME = TRUE, thresh = between 8 and 15 (depending on track length) approx. every 50 m). A portion of the GPS-corrected dead-reckoned tracks (bottom panel) are magnified (2 iterations) to show the difference in resolution of movement tortuosity, between GPS and dead-reckoned tracks

Ultimately, the higher the frequency at which dead-reckoning is undertaken, the better the resolution and detail of reconstructed tracks. However, accuracy only improves up to a point because extrapolated travel vectors (heading and speed estimates) nearly always comprise some degree of error (no matter how small) and so, with very high frequencies (> 1 Hz), more error is accumulated per unit time [cf. 16, 44]. In particular, when the temporal resolution of dead-reckoning results in a spatial resolution dominated more by sensor noise than by ‘actual’ movement of the animal in question, dead-reckoning accuracy will begin to decrease (at least pre-VPC). The extent of this will depend on the size, speed and lifestyle of the animal in question. For example, the benefits of dead-reckoning a lion at 40 Hz rather than 1 Hz are questionable (how often does a lion turn substantially within a second?), particularly given the additional computation time (cf. Additional file 1: Text S6) and possible error (relative to VPs). As such, and akin with VP under-sampling, choice of under-sampling data to be dead-reckoned may have implications to the resultant accuracy, and this will be moderated according to the scales (and media) of movement elicited by the animal in question. Beyond this, Fig. 7 also demonstrates the importance of initial track advancement, with three variants used, including step counts instead of DBA.

Finally, obtaining accurate estimates of altitude or depth allow users to plot and investigate scales of continuous movement in three dimensions and at times when VP success rate fails completely (such as underwater). We demonstrate this using the Imperial cormorant in Fig. 8. After visual inspection of data, uncorrected tracks were scaled according to the following speeds: periods of flying allocated 12 m/s, surface ‘rest’ periods allocated 0.1 m/s, bottom phase of dives allocated 0.4 m/s and descent and ascent speeds modulated according to “VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R” section—Eq. (25). Note that elevation was not resolved during flying periods (although flying periods were dead-reckoned). Regardless of the current limitations, the VPC dead-reckoning procedure represents a substantial advance for resolving, and thereby allowing investigation of, continuous, fine-scale, free-ranging 2- or 3-D space-use with all its underlying scales of tortuosity and distances moved (e.g., Figs. 7 and 8).

GPS-corrected dead-reckoned tracks of Imperial cormorants foraging at sea: a 15 birds (blue = male, red = female). b Shows one of these tracks illustrated in 3-D. Note gaps between dives are either associated with current drift, while the bird is resting at the sea surface, or periods of flight. c and d show the descent, bottom phase and ascent of a given dive in both 2-D (c) and 3-D, respectively

VPC dead-reckoning procedure in R

Preparing the three axes of rotation for derivation of heading

The tilt-compensated compass method is a well-known practice for deriving heading [e.g., 21, 22, 81]. Correct coordinate system axis alignment and suitable calibration of tri-axial magnetometry data [cf. 149] are crucial pre-processors, without which, heading estimates would likely incorporate substantial error [cf. 21, 149]. The tilt-compensated compass method described below (following the framework outlined by Pedley [21]), requires the aerospace (x-North, y-East, z-Down) (right-handed) coordinate system, or ‘NED’ (cf. Additional file 1: Text S2, Fig. S1). We provide examples of axis alignment, outline the importance of transforming between coordinate frames (relative to the Earths fixed frame) and recommend a universal configuration calibration procedure to aid correct axis alignment within Additional file 1: Text S2.

Multiple mathematically sophisticated algorithms have been developed to correct distortions from each magnetometer channel’s output [e.g., 23, 149, 150, 151, 152]. We provide an annotated R script—Gundog.Compass (Additional file 2) that corrects both soft and hard iron distortions from tri-axial magnetometry data and subsequently computes tilt-compensated heading (0° to 360°). Within this function, there are two main methods of correction to choose from, based on the mathematical protocols outlined by Vitali [153]—least-square error approximation (constructing an ellipsoid rotation matrix) and Winer [154]—scale biases with simple orthogonal rescaling (avoiding matrices altogether). We expand on this user-defined functionality, as well as outlining the causes of soft and hard iron distortions and the initial calibration procedure required to correct such distortions within Additional file 1: Text S3.

Tilt-compensated heading derivation

Device orientation is expressed in terms of a sequence of Euler angle [roll (Φ), pitch (θ), yaw (Ψ)] rotations about the x-, y- and z-axes, respectively, relative to the (inertial) Earths fixed frame of reference (e.g., Earth-Centre, Earth-Fixed (ECEF) system) [155]. Being a vector field sensor with two degrees of rotational freedom, accelerometers are insensitive to rotations about the gravity vector and thus discerning heading requires the arctangent of the ratio between the x- and y-orthogonal magnetometer measurements [156]. For the correct computation of heading, these two channels need to be aligned parallel to the earth’s surface. This is achieved by correcting any orientation (de-rotation) according to pitch and roll angles (postural offsets) which can be deduced from acceleration. These angles are typically approximated by deriving gravity-based (static) acceleration [see 72, 157] from each channel by employing one of four approaches using: (i) a running mean [e.g., 72, 86], (ii) a Fast-Fourier transformation [e.g., 158], (iii) a high-pass filter [e.g., 159] or (iv) a Kalman-filter [e.g., 160]. Here, we use a computationally simple running mean over 2 s [72] (Eq. 1):

where w is an integer specifying the window size and \(G_{x,y,z}\) and \(A_{x,y,z}\) represents the smoothed and raw components of acceleration, respectively. In the absence of linear (dynamic) acceleration [see 157, 161], values of \(G_{x,y,z}\) reflect the device orientation with respect to the earth’s reference frame (though see Table. 1), reading approx. + 1 g when orientated directly towards the gravity vector (down), − 1 g against the gravity vector (up) and 0 g at perpendicular to it (horizontal). In R, the ‘zoo’ package [126] provides useful wrappers to apply arithmetic operations in a rolling fashion (R1:4).

-

(R1)

install.packages("zoo") ; library(zoo)

-

(R2)

Gx = rollapply(Ax, width=w, FUN=mean, align="center", fill="extend")

-

(R3)

Gy = rollapply(Ay, width=w, FUN=mean, align="center", fill="extend")

-

(R4)

Gz = rollapply(Az, width=w, FUN=mean, align="center", fill="extend")

Here, w should be replaced with the window width of choice (e.g., for 20 Hz data and a smoothing of 2 s required, replace w with 40). We use a centre-aligned index (compared to the rolling window of observations), with “extend” to indicate repetition of the leftmost or rightmost non-NA value (though fill can equally be set as NA, 0, etc.).

Importantly, for correct trigonometric formulae output within the tilt-compensated compass method, the vectorial sum of static acceleration (\(G_{x,y,z}\)) and calibrated magnetometry \((M_{x,y,z}\)) measurements across all three spatial-dimensions must be normalised (to a unit vector) with a scaled magnitude (radius) of one (Eqs. 2, 3, R5:10). It was previously demonstrated that, for fast moving animals, high frequency of body posture changes could cause discrepancy between static acceleration data and magnetism data, which could consequently affect heading estimation [162]. Although this effect would not change general shapes of movement paths, we suggest that prior to the normalisation process (and magnetic calibration procedure), it may be of value to initially smooth out (see Eq. 1, R1:4) small deviations within magnetometry data, both to avoid this type of error and to reduce the magnitude of anomalous spikes in magnetic inference. We used a smoothing window of 10 events for the 40 Hz datasets used in this study.

-

(R5)

NGx = Gx / sqrt(Gx^2 + Gy^2 + Gz^2)

-

(R6)

NGy = Gy / sqrt(Gx^2 + Gy^2 + Gz^2)

-

(R7)

NGz = Gz / sqrt(Gx^2 + Gy^2 + Gz^2)

-

(R8)

NMx = Mx / sqrt(Mx^2 + My^2 + Mz^2)

-

(R9)

NMy = My / sqrt(Mx^2 + My^2 + Mz^2)

-

(R10)

NMz = Mz / sqrt(Mx^2 + My^2 + Mz^2)

Depending on deployment position, the device-carried NED coordinate frame (the x-, y-, z-axes) may not correspond with the animal’s body-carried NED frame. When this occurs, prior to deriving animal orientation, the normalised gravity and magnetic vectors are required to be corrected so that their measurements are expressed relative to the body frame of the animal [45]. This requires three rotation sequences, using 3 by 3 rotation matrices (Eqs. 4, 6) and involves two intermediate frames. The aerospace sequence used here is as follows:

-

1.

A right-handed rotation (\(C\)), about the z-axis axis of the device’s frame (\(D\)), through angle Ψ (Eq. 4), to get to the first intermediate frame (F1).

-

2.

A right-handed rotation (\(C\)) about the y-axis at \(F_{1}\), through angle θ (Eq. 5), to get to the second intermediate frame (\(F_{2}\)).

-

3.

A right-handed rotation (\(C\)) about the x-axis at \(F_{2}\), through angle Φ (Eq. 6), to get to the animal’s body frame (\(B\)).

$$C_{{F_{1} /D}}^{\left( \Psi \right)} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\cos \left( \Psi \right)} & {\sin \left( \Psi \right)} & 0 \\ { - \sin \left( \Psi \right)} & {\cos \left( \Psi \right)} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \\ \end{array} } \right]$$(4)$$C_{{F_{2} /F_{1} }}^{\left( \theta \right)} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\cos \left( \theta \right)} & 0 & { - \sin \left( \theta \right)} \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ {\sin \left( \theta \right)} & 0 & {\cos \left( \theta \right)} \\ \end{array} } \right]$$(5)$$C_{{B/F_{2} }}^{\left( \Phi \right)} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & {\cos \left( \Phi \right)} & {\sin \left( \Phi \right)} \\ 0 & { - \sin \left( \Phi \right)} & {\cos \left( \Phi \right)} \\ \end{array} } \right]$$(6)

Note the right-handed rule of rotation; a positive \({\Psi }\) reflects a clockwise rotation of the anterior–posterior axis (relative to North), a positive \(\theta\) reflects a nose-upward tilt of this axis and a positive \(\Phi\) reflects a bank angle tilt to the right about this axis. Reversing the direction of two axes causes a 180° inversion about the remaining axis and interchanging two axes (e.g., x with y) or reversing the direction of one or all three axes reverses the ‘handedness’ of rotation [right-handed—‘counter-clockwise’ vs. left-handed—‘clockwise’ (when viewed from the tip of the z-axis)]. Rotation matrices are orthogonal (unitary), with every row and column being linearly independent and normal to every other row and column. The consequence of this is that the inverse of a rotation matrix is its transpose [163] [which essentially reverses the direction of rotation, and within (Eqs. 4, 6), this is achieved by negating the sign of the sines]. Importantly, because rotation matrices are not symmetric, the order of matrix multiplication is important [45] (otherwise, Euler angles are without meaning for describing orientation). The product of the conventionally used aerospace rotation sequence outlined above (to get from the tag frame to the animal’s body frame) can be expressed as (Eq. 7).

When matrix multiplied out, this yields (Eq. 8)—often referred to as a Direction Cosine Matrix (DCM). The composition of this DCM varies according the (six possible) orderings of the three rotation matrices (Eqs. 4, 6) and the direction of intended rotation relative to the direction of measured g within the NED system (see Additional file 1: Text S2).

Note the left-handed rule of reading the vectorial notation of ordered rotations, for example \(C_{B/D}^{{\left( {\Phi , \theta , \Psi } \right)}}\) means going from the device frame to the animal’s body frame, by first rotating about the z-axis (though angle \(\Psi\)), followed by the y-axis (though angle θ) and then lastly the x-axis (though angle \(\Phi\)). The device offset can be estimated from direct observation or deduced using photographs or from the tag data itself. For example, assuming that ‘normal animal posture’ has no pitch and roll angle offset, then a tri-axial spherical plot of static acceleration [164] would show a densely populated band of datapoints at the cross-sectional origin of 0 g about the x- and y-axes, respectively, when the tag and body NED axes are in alignment.

\(NG_{x,y,z}\) and \(NM_{x,y,z}\) are pre-multiplied by the DCM to compensate for offset. However, device offset is often parametrised by roll, pitch and/or yaw angles relative to the animal’s body frame and thus, the device actually requires de-rotation (switching the ‘handedness’ of rotation) according to these values. For example, a + 45° yaw offset requires an inverse rotation about the z-axis by − 45°, rather than a further + 45° rotation. This simply involves taking the transpose of the DCM (Eq. 9), which is the same as the transpose of each of the individual rotation matrices (Eqs. 10, 11).

where \({\text{T}}\) is the matrix transpose and resultant \({\text{NGb}}_{x,y,z}\) and \({\text{NMb}}_{x,y,z}\) vectors are expressed in the animal’s body-carried NED frame. The input of these gravity and magnetic vectors are supplied as 3 by 1 column matrices for true matrix multiplication, and when expanding out (Eq. 11), this results in (Eq. 12) [substituting \({\text{NM}}\) with \({\text{NG}}\) expands out (Eq. 10)].

In R then, the alignment of device to body axes for both gravity and magnetic vectors can be performed using the following procedure (R11:22).

-

(R11)

RollSinAngle = sin(Roll * pi/180)

-

(R12)

RollCosAngle = cos(Roll * pi/180)

-

(R13)

PitchSinAngle = sin(Pitch * pi/180)

-

(R14)

PitchCosAngle = cos(Pitch * pi/180)

-

(R15)

YawSinAngle = sin(Yaw * pi/180)

-

(R16)

YawCosAngle = cos(Yaw * pi/180)

-

(R17)

NGbx = NGx * YawCosAngle * PitchCosAngle + NGy * (YawCosAngle *

PitchSinAngle * RollSinAngle - YawSinAngle * RollCosAngle) + NGz *

(YawCosAngle * PitchSinAngle * RollCosAngle + YawSinAngle * RollSinAngle)

-

(R18)

NGby = NGx * YawSinAngle * PitchCosAngle + NGy * (YawSinAngle *

PitchSinAngle * RollSinAngle + YawCosAngle * RollCosAngle) + NGz *

(YawSinAngle * PitchSinAngle * RollSinAngle - YawCosAngle * RollSinAngle)

-

(R19)

NGbz = -NGx * PitchSinAngle + NGy * PitchCosAngle * RollSinAngle +

NGz * PitchCosAngle * RollCosAngle

-

(R20)

NMbx = NMx * YawCosAngle * PitchCosAngle + NMy * (YawCosAngle *

PitchSinAngle * RollSinAngle - YawSinAngle * RollCosAngle) + NMz *

(YawCosAngle * PitchSinAngle * RollCosAngle + YawSinAngle * RollSinAngle)

-

(R21)

NMby = NMx * YawSinAngle * PitchCosAngle + NMy * (YawSinAngle *

PitchSinAngle * RollSinAngle - YawSinAngle * RollCosAngle) + NMz *

(YawSinAngle * PitchSinAngle * RollSinAngle - YawCosAngle * RollSinAngle)

-

(R22)

NMbz = -NMx * PitchSinAngle + NMy * PitchCosAngle * RollSinAngle +

NMz * PitchCosAngle * RollCosAngle

Here, Roll, Pitch and Yaw inputs denote the angular offset of the device, relative to the animal body frame. Note, standard trigonometric functions operate in radians, not degrees. In base R, π = pi. Multiplying values by pi/180 coverts degrees into radians, whilst multiplying values by 180/pi does the reverse. This rotation correction procedure is implemented within Gundog.Compass when pitch, roll and/or yaw offsets are supplied (Additional file 2).

Following the alignment of device and body axes, pitch and roll of the animal are calculated from the DCM, and because there are multiple variations in the order that rotation sequences can be composed and applied, there are also different valid equations that output different pitch and roll angle estimates, for equivalent static acceleration input. The convention is to use formulae that have no dependence on yaw rotation and restrict either the pitch or the roll angles within the range − 90° to + 90° (but not both), with the other axis of rotation able to lie between − 180° and 180°, thereby eliminating duplicate solutions at multiples of 360°. Multiplying (Eq. 8) by the measured Earth’s gravitational field vector (+ 1 g when initially aligned downwards along the z-axis) simplifies down to (Eq. 13). The accelerometer output for this aerospace rotation sequence is thus only dependent on the roll and pitch angles which can be solved (Eqs. 14, 15), allowing roll angles the greater freedom [161]. This is relevant for studies using collar-mounted tags, whereby collar may roll > 90° in either direction from default orientation.

The equation for roll (Eq. 15), however, has a region of instability at obtuse pitch angles (e.g., for NED systems, the x-axis points directly up or down, with respect to the Earth’s frame of reference). Whilst there is no ‘gold standard’ solution to this problem of singularity (using Euler angles), an attractive circumvention (detailed within [161]) is to modify (Eq. 15) and add a very small percentage (\(\mu\)) of the \({\text{ NGb}}_{x}\) reading into the denominator, preventing it ever being zero and thus driving roll angles to zero when pitch approaches −/+90° for stability (Eq. 16).

where \({\text{sign}}\left( {{\text{NGb}}_{z} } \right)\) is allocated the value + 1 when \({\text{NGb}}_{z}\) is non-negative and − 1, when \({\text{NGb}}_{z}\) is negative (recovers directionality of \({\text{NGb}}_{z}\), subsequent to the square-root). Taken together then, in R, pitch and roll are computed according to, (R24:25) with outputs within the range of − 90° to + 90° for pitch and − 180° to + 180° for roll, and this is the formula we use in the tilt-compensated method outlined below (and within Additional file 2).

-

(R23)

mu = 0.01 ; sign = ifelse(NGbz >= 0, 1, -1)

-

(R24)

Pitch = atan2(-NGbx, sqrt(NGby^2 + NGbz^2)) * 180/pi

-

(R25)

Roll = atan2(NGby, sign * sqrt(NGbz^2 + mu * NGbx^2)) * 180/pi

Here, prior to the derivation of pitch and roll, μ is allocated the value 0.01 and a vector termed ‘sign’ is created, containing 1 s and − 1 s according to the direction of measured g from \({\text{NGb}}_{z}\) (R23).

The magnetic vector of the device is then de-rotated to the Earth frame (tilt-corrected) by pre-multiplying by the product of the inverse roll multiplied by inverse pitch rotation matrix (Eq. 17), which when expanded out gives (Eq. 18).

Here \({\text{NMbf}}_{x,y,z }\) are the calibrated, normalised magnetometry data (expressed in the animal’s body-carried NED frame) after tilt-correction. Finally, yaw (ψ) (heading—now defined by the compass convention, relative to magnetic North) can be computed from the \({\text{NMbf}}_{x}\) and \({\text{NMbf}}_{y}\) (Eq. 19) via;

We outline the R code for this procedure below (R26:34).

-

(R26)

RollSinAngle = sin(Roll * pi/180)

-

(R27)

RollCosAngle = cos(Roll * pi/180)

-

(R28)

PitchSinAngle = sin(Pitch * pi/180)

-

(R29)

PitchCosAngle = cos(Pitch * pi/180)

-

(R30)

NMbfx = NMbx * PitchCosAngle + NMby * PitchSinAngle * RollSinAngle +

NMbz * PitchSinAngle * RollCosAngle

-

(R31)

NMbfy = NMby * RollCosAngle – NMbz * RollSinAngle

-

(R32)

NMbfz = -NMbx * PitchSinAngle + NMby * PitchCosAngle + RollSinAngle +

NMbz * PitchCosAngle * RollCosAngle

-

(R33)

Yaw = atan2(-NMfby, NMfbx) * 180/pi

-

(R34)

Yaw = ifelse(Yaw < 0, Yaw + 360, Yaw)

Note, yaw output from (R33) uses the scale − 180° to + 180°. (R34) converts to the scale 0° to 360o (specifically, 0° to 35\(\dot{9}\)°). This is also achieved by using a modulus (mod) operator (Eq. 20, R35), which in base R takes the form %%.

-

(R35)

Yaw = (360 + Yaw) %% 360

Magnetic declination is defined as the angle on the horizontal plane between magnetic north and true north [165]. Prior to dead-reckoning, magnetic declination should be summed to heading values to convert from magnetic to true North [166]. There are many online sources to calculate the magnetic declination of an area [e.g., 167]. Notably, logical corrections may need to be performed to ensure data does not exceed either circular direction after applying magnetic declination (R36).

-

(R36)

h = ifelse(h < 0, h + 360, h) ; h = ifelse(h > 360, h - 360, h),

where h refers to the vector containing the heading data. Should the user not correct for axis alignment between the device and animal body frame (cf. Eqs. 4–12, R11:22) then a reasonable post-correction for small discrepancies about the yaw axis would be to subtract the difference to h values at this point.

Preparing speed estimates

The vectorial dynamic body acceleration (VeDBA) (Eq. 21) [cf. 67, 168] was our choice of DBA-based speed proxy for terrestrial dead-reckoning purposes. This is given by:

where \(v\) represents VeDBA, \(D_{x}\), \(D_{y} \;{\text{and}}\;D_{z}\) are the dynamic acceleration values from each axis, themselves obtained by subtracting each axis’ static component of acceleration (cf. Eq. 1, R1:4) from their raw equivalent (R37).

-

(R37)

v = sqrt((Ax - Gx)^2 + (Ay - Gy)^2 + (Az - Gz)^2),

where Ax, Ay, Az and Gx, Gy, Gz are the raw and static (smoothed) values of each channel’s recorded acceleration.

We recommend implementing a running mean (cf. Eq. 1, R1:4) to raw VeDBA values to ensure that both acceleration and deceleration components of a stride cycle are incorporated together per unit time and to reduce the magnitude of small temporal spikes (likely not attributable to the scale of movement elicited [cf. 97]. Choice of smoothing window size is dependent on the scale of movement being investigated, though as a basic rule, we suggest 1 to 2 s. For similar reasons, it is also worth post-smoothing raw pitch, roll and heading outputs, although heading requires a circular mean (Eqs. 22, 23) [cf. 169]:

where \(h_{j}\) and \({\overline{\text{h}}}\) are the unsmoothed and smoothed heading values, \(\overline{\theta }_{p}\) the arithmetic mean after converting degrees to cartesian coordinates and \(\bmod\) refers to the modulo operator.

In R, the above formula can be made into a function (R38), to be applied within the ‘rollapply’ wrapper (replacing ‘FUN = mean’ with ‘FUN = Circ.Avg’) (cf. R1:4).

-

(R38)

Circ.Avg = function(x){

H.East = mean(sin(x * pi / 180))

H.North = mean(cos(x * pi / 180))

MH =( atan2 (H.East, H.North)) * 180 / pi

MH = (360 + MH) %% 360

return (MH)

}

Speed (\(s\)) can be estimated from VeDBA (\(v\)) via (Eq. 24).

where \(m\) is the multiplicative coefficient and \(c\) is a constant [10, 69]. Here, a user can define various bouts of movement from motion sensor data (e.g., via various machine-learning approaches (for review see Farrahi et al. [170]) or the Boolean-based LoCoD method [101]) and/or substrate condition (e.g., via GPS), to be cross-referenced when allocating variants of the speed coefficients. As a simple example, in R, should walking (coded for as 1) and running (coded for as 2) be teased apart from all other (non-moving) data (coded for as 0) within a Marked Events vector (ME), then ME can be used to allocate various \(m\) (and if applicable, \(c\)) values using simple ‘ifelse’ statements (R39:40).

-

(R39)

m = ifelse(ME == 1, 1.5, ifelse(ME == 2, 3.5, 0))

-

(R40)

c = ifelse(ME > 0, 0.1, 0)

Here, walking is given an arbitrary coefficient of 1.5 and running, 3.5 with a value of 0.1 for their constants. All other ME values are given a 0 coefficient and 0 constant, which results in no speed at such times, regardless of DBA magnitude.

By-passing DBA as a speed proxy

Dividing the number of steps detected within a given rolling window length (cf. R1:4), by the window length (s) gives an estimated step count per second. This can be converted to speed by multiplying by a distance per step estimate (assuming constant distance travelled between step gaits). We review this further in Additional file 1: Text S4, including a simple peak finder function—Gundog.Peaks (Additonal file 3) that locates peaks based on local signal maxima, using a given rolling window, with each candidate peak filtered according to whether it surpassed a threshold height (in conjunction with other potential user-defined thresholds). Note, this method can equally be applied to non-terrestrial species, using flipper/tail beats instead, where appropriate.

For diving animals, a proxy for horizontal speed can be obtained based on animal pitch and rate change in depth [47, 116]. Specifically, rate change of depth (\(\Delta d\)) (units in m/s) is divided by the tangent of pitch (\(\theta\)) (converted from degrees to radians) (Eq. 25):

Here, resultant speed values need to be made absolute (positive). This calculation is only valid when the direction of movement is the same as the direction of the animal’s longitudinal axis (equal pitch assumption) [cf. 47] and thus should only be calculated at times when the animal is travelling ‘ballistically’ (at considerable vertical speed).

-

(R41)

s = ifelse(abs(p) >= 10, abs(RCD / tan(p * pi/180)), s)

In the above example (R41), nominal speed values are overwritten with the trigonometric formula output (Eq. 25) at times of ‘appreciable’ pitch (10°) [cf. 171], where RCD is the rate change of depth and p is the pitch (in radians). An upper limit should be imposed on speed values derived in this way because values can become highly inflated when the pitch angle is particularly acute.

Converting speed to a distance coefficient

Speed (s) estimates are multiplied by the time difference between the values (\({\text{TD}}\)) to give a distance estimate (units in metres) which, in turn, standardises coefficient comparisons across datasets sampled at different rates. These distance values are then divided by the approximate radius of the earth (R = 6,378,137 m) to give a radial distance coefficient (\(q\)) [see 172] (Eq. 26)”

Assuming that high-resolution depth data are not available, but ‘absolute’ speed estimates have been obtained, then an alternative to Eq. 25, (in accordance with the equal pitch assumption) is to derive horizontal distance estimates by multiplying the absolute distance by the cosine of the pitch (\(\theta\)) (converted from degrees to radians), which can equally be performed on the radial distance (Eq. 27):

In R, to determine accurate lengths of time between values, it is best to save date and time variables together as POSIX class [173]. Creating timestamp (TS) objects with POSIXct class enables greater control and manipulation of time data. This makes computing the rolling time difference (\({\text{TD}}\); units in seconds) between data points simple (R42):

-

(R42)

TD = c(0, difftime(TS, lag(TS), units = "secs")[-1])

We detail how to create timestamp objects of POSIXct class within Additional file 1: Text S5, including formatting with decimal seconds (important for infra-second datasets) and various codes useful for manipulating data to be dead-reckoned based on time.

In R then, following the computation of \({\text{TD}}\), \(q\) is obtained via (R43:44).

-

(R43)

s = (v * m) + c

-

(R44)

q = (s * TD) / 6378137

Note, if a negative c intercept is used (e.g., to allow for some body movement without translation), then any negative speed values would need to be equated to zero as an additional step.

As previously mentioned, the ME vector (progressive movement coded by integer values greater than zero (e.g., 1) and stationary behaviour coded by zero) can be used to ensure q (essentially the distance moved) is zero when ME reads zero, ensuring dead-reckoned tracks are not advanced at such times, regardless of the computed speed (R45).

-

(R45)

q = ifelse(ME == 0, 0, q)

Derivation of coordinates

Once \(q\) and \(h\) are obtained, coordinates are advanced using (Eqs. 28, 29);

where \({\text{Lat}}_{0}\), \({\text{ Lat}}_{i}\) and \({\text{Lon}}_{0}\), \({\text{ Lon}}_{i}\) are the previous and present latitude and longitude coordinates, respectively (in radians), \(h\) is the (present) heading (in radians) and \(q\) is the (present) distance coefficient.

In R, the above can be performed iteratively within a for-loop (iteration of code repeated per consecutive \(i{\text{th}}\) element of data; R49). Initialising the output latitude (DR.lat) and longitude (DR.lon) variables to the required length (e.g., as governed by the vector length of other input data (heading, speed, etc.) speeds up processing time (R46). Within the trigonometric dead-reckoning formulae, the starting latitude (la) and longitude (lo) coordinates and heading (\(h\)) values must be supplied in radians (R47). The la and lo values are saved as the first elements of the DR.lat and DR.lon vectors to be advanced, respectively (R48).

-

(R46)

DR.lat = rep(NA, length(h)) ; DR.lon = rep(NA, length(h))

-

(R47)

la = la * pi/180 ; lo = lo * pi/180 ; h = h * pi/180

-

(R48)

DR.lat[1] = la DR.lon[1] = lo

-

(R49)

for(i in 2:length(DR.lat)) {

DR.lat[i] = asin ( sin (DR.lat[i-1]) * cos (q[i]) n+ cos (DR.lat[i-1]) *

sin (q[i]) * cos (h[i]))

DR.lon[i] = DR.lon[i-1] + atan2 ( sin (h[i]) * sin (q[i]) *

cos (DR.lat[i-1]), cos (q[i]) - sin (DR.lat[i-1]) * sin (DR.lat[i]))

}

Reverse dead-reckoning

For this, firstly, the time difference is computed as usual (R50) and the dimensions of each vector required in the dead-reckoning calculation are reversed. We bind all relevant vectors into a data frame (df) (R51), subsequent to reversing data frame dimensions (R52); the last row becomes the first row, second to last row becomes the second, etc. Note, this can equally be achieved by using the rev() function within base R, on each individual vector. These reversed columns are now restored as vectors (R53) and shifted forward by one element (R54). This is required for correct alignment in time so that dead-reckoning works in exactly the opposite manner to ‘forward’ dead-reckoning.

-

(R50)

TD = c(0, difftime(TS, lag(TS), units = "secs")[-1])

-

(R51)

df = data.frame(TD, h, v, m, c, ME)

-

(R52)

df = df[dim(df)[1]:1, ]

-

(R53)

TD = df[, 'TD'] ; h = df[, 'h'] ; v = df[, 'v'] ;

m = df[, 'm'] ; c = df[, 'c'] ; ME = df[, 'ME']

-

(R54)

TD = c(NA, TD[-length(TD)]) ; h = c(NA, h[-length(h)]) ;

v = c (NA, v[ -length(v)]) ; m = c (NA, m[ - length (m)]) ;

c = c (NA, c[ -length (c)]) ; ME = c (NA, ME[ -length (ME)])

The next step is to rotate heading 180° and correct for its circular nature (R55).

-

(R55)

h = h - 180 ; h = ifelse(h < 0, h + 360, h)

Lastly, \(q\) is determined and DR.lon and DR.lat are advanced based on the dead-reckoning formula (cf. R46:49), except in this instance, the first element of DR.lon and DR.lat needs to be supplied by the ‘known’ last lo and la coordinates.

Integrating current vectors

In R, current vectors can be added according to (R56:60). Current speed (cs) is in m/s (ensure values are absolute) and current heading (ch) uses the scale 0° to 360°. Note the use of ‘yy’ and ‘xx’ vectors, storing the previous DR.lat and DR.lon coordinates prior to implementing the next ‘current drift’ vector per iteration. The current speed is also standardised according to the time period length and Earth’s radius (analogous to the derivation of \(q\)). When reverse dead-reckoning, it is important to ensure that cs and ch are included in the steps outlined above (R50:55).

-

(R56)

DR.lat = rep(NA, length(h)) ; DR.lon = rep(NA, length(h))

-

(R57)

xx <- rep(NA, length(cs)) ; yy <- rep(NA, length(cs))

-

(R58)

la = la * pi/180 ; lo = lo * pi/180 ;

h = h * pi/180 ; ch = ch * pi/180

-

(R59)

DR.lat[1] = la DR.lon[1] = lo

-

(R60)

for(i in 2:length(DR.lat)) {

DR.lat[i] = asin ( sin (DR.lat[i-1]) * cos (q[i]) + cos (DR.lat[i-1]) *

sin (q[i]) * cos (h[i]))

yy[i] = DR.lat[i]

DR.lon[i] = DR.lon[i-1] + atan2 ( sin (h[i]) * sin (q[i]) *

cos (DR.lat[i-1]), cos (q[i]) - sin (DR.lat[i-1]) * sin (DR.lat[i]))

xx[i] = DR.lon[i]

DR.lat[i] = asin ( sin (yy[i]) * cos ((cs[i] * TD[i]) / 6378137) +

cos (yy[i]) * sin ((cs[i] * TD[i]) / 6378137) * cos (ch[i]))

DR.lon[i] = xx[i] + atan2 ( sin (ch[i]) * sin ((cs[i] * TD[i]) /

6378137) * cos (yy[i]), cos ((cs[i] * TD[i]) / 6378137) - sin (yy[i]) *

sin (DR.lat[i]))

}

VPC procedure

Specifically, this method entails calculating the difference of Haversine distance (net error) and bearing (from true North) between consecutive VPs and the corresponding time-matched dead-reckoned track positions. The trigonometric Haversine formulae (Eqs. 30, 31) are used to calculate the great-circle distance (\(d\)) and great circular bearing (\(b\)) between consecutive VPs and consecutive (time-matched) dead-reckoned positions (note we use the term ‘bearing’ to differentiate between heading estimates from motion data—though they are essentially the same).

where R is the Earth’s radius and \(d\), the output in metres.

where \(\Delta {\text{Lon}}\) represents \({\text{Lon}}_{i}\) − \({\text{Lon}}_{0}\), \(\Delta {\text{Lat}}\) represents \({\text{Lat}}_{i}\) − \({\text{Lat}}_{0}\) and \(b\) output is in the scale − 180° to + 180°. To convert \(b\) to the conventional 0° to 360° scale, 360 should be added to values < 0.

For each VP, the distance is divided by the dead-reckoned distance providing a distance correction factor (ratio; Eq. 32). The heading correction factor is computed by subtracting the dead-reckoned bearing from the VP bearing (Eq. 33). To ensure that difference does not exceed 180° in either circular direction, 360 should be added to values < − 180 and 360 subtracted from values > 180. A simple example of why this is relevant can be illustrated by subtracting a dead-reckoned bearing value of 359° from a VP bearing value of 1°—post-correction, the difference is + 2°.

All intermediate \(q\) values are multiplied by the distance correction factor and the heading correction factor is added to all intermediate \(h\) values (ensuring that \(h\) values are in degrees). To ensure circular range is maintained between 0° and 360°, 360 should be subtracted from values > 360 and added to values < 0.

Specifically, we follow the protocol illustrated within Fig. 9 for intermediate values. Note the formulae to calculate both distance (\(d\); Eq. 30) and bearing (\(b\); Eq. 31) between two points, are also used to recalculate both the heading (\(h\)) and radial distance (\(q\)) between current-integrated dead-reckoned fixes (pre-VPC; cf. R60). Note that the Haversine distance is required to be converted back to radial distance by dividing by R (R = 6,378,137).

Schematic diagram illustrating the order of fixes used when calculating the \({\text{ Distance}}_{{{\text{corr}}.{\text{factor}}}}\) and \({\text{Heading}}_{{{\text{corr}}.{\text{factor}}}}\) (difference of both GPS and dead-reckoned (DR) positions between arrow heads). Note the discrepancy with the order at which these correction factors are applied to intermediate DR positions (as denoted by colour shading). Known starting position denoted with asterisk

In R, the formulae to calculate the great-circle distance and great circular bearing are saved within the disty (R61) and beary (R62) functions, respectively, where lon1, lat1, long2 and lat2 represent longitude and latitude positions (decimal format) at \(t_{i}\) and \(t_{i + 1}\), (\(t\) representing time).

-

(R61)

disty = function(long1, lat1, long2, lat2) {

long1 = long1 * pi/180 ; long2 = long2 * pi / 180 ; lat1 = lat1 *

pi / 180 ; lat2 = lat2 * pi / 180

a = sin ((lat2 - lat1) / 2) * sin ((lat2 - lat1) / 2) + cos (lat1) *

cos (lat2) * sin ((long2 - long1) / 2) * sin ((long2 - long1) / 2)

c = 2 * atan2 (sqrt (a), sqrt (1 - a))

d = 6378137 * c

return (d)

}

-

(R62)

beary = function(long1, lat1, long2, lat2) {

long1 = long1 * pi / 180 ; long2 = long2 * pi / 180 ; lat1 = lat1 * pi / 1

80 ; lat2 = lat2 * pi / 180

a = sin (long2 - long1) *cos (lat2)

b = cos (lat1) * sin (lat2) - sin (lat1) * cos (lat2) * cos (long2 - long1)

c = (( atan2 (a, b) / pi) * 180)

return (c)

}

Below, we outline an example of VPC in R and assume VP coordinates (decimal format) are aligned in the same length vectors/columns as motion sensor-derived data, e.g., heading, DBA/speed, etc., with the corresponding indexed (element-/row-wise) time. Typically, motion sensor data are recorded at much higher frequency so that there are many dead-reckoned fixes between sequential VPs. As such, in the example below, we assume NAs are expressed in the VP longitude and latitude fields at times of missing locational data. This approach of synchronising VP—with motion sensor data also applies when integrating current data; assuming ch and cs are element/row-wise matched to the relevant VP grid node.

Firstly, an indexing row number (Row.number) vector, the length of the data used in the dead-reckoning operation (e.g., \(h\)) is created (R63), which is relevant for merging full-sized and under-sampled data frames together (seen later). Together, the row number, (uncorrected) dead-reckoned longitude and latitude coordinates, VP longitude and latitude coordinates, heading and the radial distance vectors are inputted column-wise into a ‘main’ data frame, termed ‘df’ (R64; user-assigned column names of each vector are within quotation marks). This data frame is then filtered removing rows with missing VP data and stored as df.sub (R65). This under-sampled data frame thus, row-wise, contains the time-matched dead-reckoned and ground-truthed positions. The VPC process is analogous for reverse dead-reckoned tracks—although VP.lon and VP.lat must also be reversed [Row.number remains in ascending order (not reversed)]. The first element of VP.lon and VP.lat must be the lo and la, respectively (or for reverse dead-reckoning, the last element prior to reversing these vectors).

-

(R63)

Row.number = rep (1 :length (h))

-

(R64)

df = data.frame (Row.number, 'DR.longitude' = DR.lon,

'DR.latitude' = DR.lat, 'VP.longitude' = VP.lon,

'VP.latitude' = VP.lat, h, q)

-

(R65)

df.sub = df[ !with (df, is.na (VP.longitude) | is.na (VP.latitude)) ,]