Abstract

Background

We present a cellular phone-enhanced GPS tracking system (GPS mobile with CTG-001G receiver triangulation) suitable for urban carnivores, in tandem with appropriate home range analysis, as an additional tracking technology option in metropolitan settings. We conduct this proof-of-concept study working with the management of introduced invasive raccoons in Japan (and conditions implicit to this control program).

Results

Each tracking period averaged 17 days, and a tracking accuracy of < 50 m error was achieved in over 30% of the fixes. Variogram analysis demonstrates that these data were of sufficient quality to support home range analysis. Home range areas estimated from these data revealed that raccoons in urban Japan likely range over a much greater area than has previously been reported.

Conclusions

As a proof of concept, these prototype collars were successful in tracking raccoons in the difficult suburban environment, where this system (CTG) made fixes against FOMA antennae-augmented GPS and yielded data that could support home range analysis. We advocate further research and development to refine this system, with broad application as a tool to diversify wildlife tracking technology options in urbanized environments, where synanthropic and/or invasive species can cause a nuisance warranting effective management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although urbanization presents a growing threat to wildlife [1, 2], many generalist species are proving highly adaptable to human-modified landscapes [3]. Notably, various medium-sized carnivores, such as red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), raccoons (Procyon lotor), martens (Martes spp.) and coyotes (Canis latrans), now flourish across urbanized environments (e.g., [4, 5]), because they are able to modify their behavior [6] and/or exploit novel foraging opportunities, such as waste from households and restaurants [7, 8]. Although mesocarnivores do not instigate the level of deterrence and removal strategies elicited by large and potentially dangerous carnivores (e.g., bears, Ursidae, [9]; leopards, Panthera pardus, [10]), they can still pose a serious nuisance by upturning garbage cans, contaminating areas with feces, or causing a hazard on highways [8]. Effective management of human wildlife conflicts [11] is especially important when introduced and/or invasive species are involved [12], or when mesocarnivores also carry serious zoonotic diseases [13]. For example, skunks (Mephitis spp.) and raccoons are a major rabies host in urban centers in North America [14]. To better inform the design of human–wildlife conflict mitigation [15, 16], it is therefore paramount to develop technologies better able to track urban carnivores in this challenging environment. Ideally, such telemetry systems must yield data able to support home range analysis [17, 18], where techniques such as VHF tracking can sometimes be hampered by the extent of private land ownership in suburban areas, because researchers must access multiple points for accurate positional triangulation [19]. Electrical interference from household appliances can also pose problems, as can the obstruction of radio signals by buildings [20]. Although GPS (global positioning system) tracking circumvents some of these problems [21], systems can suffer from low positional accuracy and habitat bias [22], due to poor line of sight to orbiting satellites, and archival GPS also results in a delay until data download. Where GPS data download directly via satellite, costs can be prohibitive (discussed in [23,24,25]).

Here we undertook a proof-of-concept study to develop and test a prototype cellular phone-based tracking system, triangulating positional fixes relative to network antennae to compensate for the loss of GPS connectivity among urban structures (e.g., [20, 26]). We conducted this trial in suburban Tokyo, using the network of FOMA base stations/antennae (an abbreviation for Freedom Of Mobile Multimedia Access—a third-generation (3G) mobile communication service provided by NTT Docomo Inc., the predominant cellular phone service provider in Japan). This approach of combining GPS and PHS (Personal Handy-phone System) was first adapted for wildlife tracking in Japan by Saeki et al. [27], who developed the personal location application offered by Japan’s commercial network system (equivalent to GSM or DECT in other global regions) to acquire positional information for tracked animals continuously and remotely in real time. The cost of this system was modest, at c. 97,000 JPY (< US$ 900, including hardware purchase and network fees) per animal for a 3-month study, with approximately half of this cost being related to data transmission [28]. This pioneering tracking system reliably achieved mean positional errors < 20 m in stationary tests and < 60 m in moving tests [27, 28], although it suffered from short battery life, as well as positional errors as large as 100 m in actual deployment, for example, as reported by Morishita et al.’s [29] study on jungle crows (Corvus macrorhynchos).

Advances in the 3G (third-generation) telecommunications, using W-CDMA (Wideband Code Division Multiple Access), have provided significant improvements in positional accuracy. This has been used in Japan to track endemic raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides [20]), and has been applied to a feasibility study tracking invasive raccoons [30]. Building on this preliminary work, here we test a system combining a positional information terminal (CTG-001G, from Japanese cellular company NTT Docomo Inc., hereafter CTG) with a built-in onboard GPS function, compatible with the FOMA 3G telephone network—(for full technical details see [27, 28]). We apply this system to track invasive raccoons, as a pertinent model species. Raccoons were first introduced to Japan in 1964 [31] and have now been confirmed in 44 of Japan’s 47 prefectures, quickly invading Japan’s urban centers [32, 33]. The Japanese government’s current policy (Invasive Alien Species Act, 2004) is to attempt to eradicate raccoons across Japan, due to intra-guild competition with native carnivores [34], their involvement as a vector of various zoonotic diseases [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], but particularly the general nuisance they cause by invading homes, upturning garbage cans, and damaging crops [43]. The scale of this intervention can be seen in numbers killed across Japan increasing from 24,874 in 2010 to 38,319 in 2015 [44, 45].

Our aims here were to provide a proof-of-concept test of CTG functionality for tracking urban carnivores in a metropolitan setting, in particular, whether cellular phone-enhanced GPS tracking could generate data of sufficient quality to support home range (HR) analysis, where Burt [46] defined HR as the area traversed by an individual in its normal activities of food gathering, mating, and caring for young. Many analytical methods have been developed to estimate home range area, and here we apply autocorrelated kernel density estimation (AKDE [47]), which can account for the autocorrelation structure inherent in tracking data [47,48,49]. However, to compare the results from these novel tracking data with previous studies on space use in urban raccoons, we also applied conventional kernel density estimation (KDE [50]) with Gaussian reference function bandwidth optimization. We then use our findings to comment on the limitations and potential for refinement of this CTG technology for future deployments.

Results

System efficiency

Seven adult raccoons were collared, six males (B1–2, M1–4) and one female (F1), which was lactating when captured and then continued to be detected (also by ancillary camera trapping) around her natal den area. One of these male raccoons (M1) was re-captured and collared a second time. Each raccoon was tracked for between 4.3 and 56.8 days (median = 17.2; Table 1; Fig. 1). The 24 h sampling regime at 1 h intervals yielded significantly more nocturnal than diurnal positional measurements (t test, p = 0.011). The resulting median success rate for obtaining a positional measurement was therefore 49.4% (range 31.0–68.6%). Nevertheless, across both regimes, the system yielded a median of 203.5 (range 65–690) CTG-GPS positional locations per animal. The median accuracy of each fix was 140 m (range 7 to 4900 m; SD: 1632.8). For those fixes that were acquired, positional error rates were similar by day and night (t test, p = 0.059).

Despite CTG complementing the base GPS tracking, high fix failure rate resulted in unanticipated battery expenditure while devices searched for raccoons that were out of contact, likely in their diurnal dens. The maximum continuous operation lifespan (i.e., hourly sampling over 24 h) of collars was on average of just 23.0 days under continuous hourly operation (regime 1) and 13.0 days under nighttime only/30 min operation (regime 2), substantially shorter than the projected 90 days. Notably, the 30 min nighttime-only sampling regime supported relatively shorter sampling periods (12.2 days ± 6.7 SD) than the 1 h interval regime.

Evaluating data quality

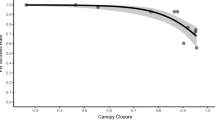

Although the median number of fixes obtained for each individual was 204, the median effective sample size was only 34.1 (95% CI 2.2–133.9; Table 2). Nonetheless, these tracking data were of sufficient resolution to distinguish different inter-individual movement patterns, as demonstrated by the variance in range crossing times between tracked raccoons (median = 12.2 h 95% CI 1.8–40.2). All tracked raccoons were determined to be range resident, as evidenced by asymptotic variograms (Fig. 2). Both the 60 min and 30 min sampling regimes yielded sufficient data for home range analysis, although the 30 min sampling regime provided more information on the fine-scale features of raccoon movement (Fig. 2c, d).

Variograms contrasting the two most representative individuals for a the 60 min sampling regime—individual B1; and b the 30 min sampling regime—individual M2. The black line and gray shading depict the semi-variance ± 95% CIs, whereas the red line and shading depict the fitted movement model ± 95% CIs of the model fit. The lower panels shows the fine-scale features of these variograms under c the 60 min sampling regime for raccoon B1; and d the 30 min sampling regime for raccoon M2. Note that in a and b the semi-variance reaches an asymptote, evidencing range residency—i.e., the time required to reach the asymptote is roughly the home range crossing time. Although both sampling regimes produced sufficient data for home range analysis, the 30 min sampling regime provided more fine-scale information, and an improved model fit at short time lags

Home range estimates

The median home range size of the tracked raccoons was 18.2 km2 (range 3.32 km2–223.4 km2) when estimated via AKDE, but only 9.1 km2 (range 3.31 km2–42.7 km2) when estimated via KDE with unmodeled autocorrelation. Range estimates varied substantially between individuals, although the small number of individuals we were permitted to release for tracking precluded formal analysis of inter-individual differences. AKDE 95% home range estimates were larger than KDE range estimates by, on average, a factor of 2.7 ± 1.5 SD. KDE and AKDE were similar in just one instance where raccoon F1 yielded the largest effective sample size, and consequently the best resolved range (Fig. 3a, b). Conversely, the short sampling duration (4.4 days), and long range crossing time (47.3 h) of M1’s winter tracking session resulted in it having the lowest effective sample size, and for this individual KDE estimated its home range as being more than fivefold smaller when compared to AKDE (42.7 km2 versus 223.4 km2 respectively). Although we tracked only one female, its 95% home range was substantially smaller than the median male range size (3.3 km2 versus 24.1 km2 ± 71.4 SD).

Maps depicting KDE and AKDE home range estimates contrasting the most representative individuals F1 and M2. The top two panels depict the a KDE range and; b AKDE 95% area estimates ± 95% CIs for raccoon F1. F1’s short range crossing time (1.8 h), and long tracking duration (22.6 days) resulted in an effective sample size of 303.6, and both KDE and AKDE produced well-resolved ranges. The bottom two panels depict the c KDE range and; d AKDE 95% area estimates ± 95% CIs for raccoon M2. M2’s comparatively longer range crossing time (40.2 h), and shorter tracking duration (19.7 days) resulted in fewer range crossing events being observed, and an effective sample size of only 11.8. Here KDE underestimated the home range area by more than threefold, whereas AKDE produced a larger, and less biased range estimate

Discussion

Broadly, this CTG system performed adequately in this suburban area of Tokyo, which had a saturation of FOMA base station antennae to triangulate from, and showed potential for further device refinement and system development. Positional fixes were, on average, 54.3% successful, although only 27.3% of these data had an error range of less than 50 m. Nevertheless, this prototype system informed a sufficient number of range crossing events to permit home range estimation for all raccoons tracked.

One notable area of weakness was device battery life, which did not match our expectations of lasting around 90 days. Batteries actually lasted on average of just 23.0 days under continuous hourly operation (regime 1) and 13.0 days under nighttime only/30 min operation (regime 2). While the 30 min nighttime-only sampling regime did not improve battery life significantly, it did provide more information on the fine-scale features of individual movement behaviors. It should be noted, however, that for animals with longer range crossing times that the longer duration provided by the 60 min sampling regime might be more suitable, and researchers should tailor their sampling protocol to both the questions of interest and the species’ biology. We infer that much of this reduced battery life was the result of raccoon denning behavior, preventing collars from contacting GPS satellites and placing more functionality onto CTG triangulation using base stations, where positional accuracy relates to antennae coverage and signal power density. Extending battery life and balancing the trade-off between study longevity versus the resolution of tracking is thus a priority for future CTG deployments, where ever-improving lithium-ion battery technology (greater longevity with lighter weight [51]) should be incorporated into future design refinements. In this regard, we anticipate that total device weight could be reduced in the future.

In terms of home range analysis, these data supported effective AKDE home range estimates, which incorporated information on both the autocorrelation between relocations, and the positional error of each fix [52,53,54]. Statistically, our AKDE range estimates were at least twice as large as when computing conventional KDE ranges from these tracking data, which is consistent with the differences between KDE and AKDE observed in other studies [55]. Furthermore, despite KDE’s well-documented pathology of underestimating home range areas on autocorrelated data [55], even the likely negatively biased median 9.3 km2 home range area estimated via KDE using our novel CTG technology was more than fivefold larger than the ca. 1.7–2.0 km2 reported by other studies from Japan (e.g., [43, 56,57,58]). Noting that these previous studies on raccoons in Japan typically utilized radio tracking techniques combined with KDE and MCP methods. This suggests that a larger-scale effort to re-establish the home range size of urban raccoons in Japan with more contemporary tracking technologies and analytical techniques might be warranted.

Two of the males we tracked, and the single female, were neutered, as required by permits to release raccoons in Japan, and this could have influenced their ranging behavior. One might, however, anticipate that neutered individuals would range less, not more. Note also that raccoons M1–M4 were only vasoligated (after negotiation with government officials), so as not to affect testosterone production, and thus have less impact on their behavior. Furthermore, the individual M2, that had to be relocated to permit release, traveled ca. 5 km to return to the area in which it was trapped. Importantly, this provides anecdotal evidence that translocation is unlikely to be an efficient means of controlling local raccoon densities unless translocation distances are much greater than the upper range size, though we propose that a more thorough investigation into this topic is warranted.

Alternatively, greater home range size than expected may have been a feature of the distribution of key food resources in time and space in this heterogeneous suburban habitat mosaic [59, 60]. For instance, Prange et al. [61] also point out that the spatial distribution of anthropogenic resources and barriers to utilization can affect raccoon home ranges very substantially, which is especially applicable to core areas. The key, however, was that our prototype tracking system was able to collect home range data under these realistic conditions applied to managing human–wildlife conflicts with synanthropic carnivores.

Conclusions

Accurate and effective home range analysis is crucial for planning the management of synanthropic carnivores, often involved in human wildlife conflicts in urban areas [8, 62, 63]. CTG tracking proved effective for yielding data suitable for AKDE analysis, and revealed larger home ranges than studies using more conventional tracking technologies. CTG therefore has substantial potential for development and refinement as a telemetry application in urbanized environments that have good mobile network service where the deployment of other comparable technologies may sometimes be compromised.

Methods

Study area

This pilot investigation was carried out in the Ibaraki Prefecture, across 200 km2 in the suburbs of Bando City and Joso city (36°00′N; 139°54′E; Fig. 4). This is specified as a priority area in the “Common raccoon extermination plan in the Ibaraki Prefecture” [44, 64] due to an ever-worsening raccoon problem since raccoons first colonized Ibaraki prefecture in the 1990s [65]. This is reflected by numbers trapped and killed: 5 (2008), 39 (2009), 58 (2010), 74 (2011), 90 (2012), 120 (2013), 139 (2014), 295 (2015) [44, 45], although trapping effort has also increased as the government attempts complete raccoon eradication from the entire area as part of the broader national extermination strategy. This area comprises high-density residential housing, interspersed with farmland, with a human population of 114,257 residents within the 246.7 km−2 combined metropolitan area of Joso city and Bando city. Almost the entirety of this study region was covered by the FOMA network service (see NTT DOCOMO service coverage map: https://www.nttdocomo.co.jp/support/area/).

Location of study area. The study area was located in central Japan (a), extending over Bando city and Joso city in the Ibaraki Prefecture. It covered 200 km2 including a 232 ha swamp called “Sugo-numa” (b). Rice and crop fields, forest and residential area are fragmented like a mosaic surrounded by rivers and creeks. All trap sites and all fixes were obtained using GPS/CTG on the FOMA network

Trapping raccoons and fitting CTG tracking devices

Under this Ibaraki Prefecture raccoon eradication program, we gained special permission to be able to capture, instrument and release eight raccoons (seven adults and one yearling—the yearling was still growing and was not collared) between November 2010 November 2012, around the cities of Bando and Joso. Raccoons were trapped in modified Tomahawk Live Traps (Model 207.5, Tomahawk, Wisconsin, USA) with optimized trigger mechanisms [66], using roasted peanuts and marshmallows as bait. Traps were checked and re-baited every morning. Captured raccoons were taken to a local veterinary clinic, where they were immobilized by a veterinarian using isoflurane gas. Biometric parameters (e.g., head–body length, tail length, weight, age class, sex) were recorded for each animal, and tracking collars fitted. We constructed prototype collars using commercially available components to progress with this proof-of-concept study phase, acknowledging scope to substantially refine collar design if this technology proved worthy of further research and development. The tracking device comprised a CTG chipset with integrated GPS and FOMA transmitter, plus a 6000 mAh lithium-ion battery, housed in a smooth rounded waterproof rubber and silicon-sealed module 80 mm × 50 mm × 40 mm, attached to nylon collar (38 mm width). Total assembly weight was 257.8 ± 30.9 g, which is around 3% of the mean weight of raccoons used in this study (8.0 ± 1.2 kg; see Table 1) and consistently less than the 5% threshold recommended by the American Society of Mammalogists ([67], see also [68]). Raccoons are sturdy generalists that can vary their body weight by up to 50% seasonally [69], and were thus well suited as a model species for this deployment. Furthermore, raccoons will attempt to remove and damage tracking devices, risking injury and jeopardizing study objectives, hence devices must be robust, although we fully recognize the importance of reducing device weight during future research and development [70].

Because this study was integrated into an invasive control program, the re-release of raccoons for tracking was only permitted after neutering. Males were castrated (n = 2/6: B1 and B2) or vasoligated (ligation of the vas deferens; n = 4/6: M1, M2, M3, and M4), and the single female tracked (F1) was administered a subcutaneous sterilization implant. We concede that this procedure is likely to influence the ranging behavior of individuals (in relation to mating, foraging should be less affected); however, this is representative of the type of management conditions often applied as a non-lethal alternative when managing human–wildlife conflicts with urban invasive carnivores (e.g., [71, 72]), and so provided an appropriate and representative test for our prototype system.

After this procedure, raccoons were left for at least 2 h to recover from anesthesia and then released at their capture sites whenever possible. Our permission from local government mandated that one male (M2) had to be released at a different location, 5.2 km from its capture site, due to strong objection from a farmer who had suffered serious crop damage. Again, this was representative of the type of urban carnivore management we wanted to include in our test, where displaced individuals may range farther, and thus present a particular tracking challenge. All trapping and handling procedures conformed with the Association for the Study of Animal Behavior guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioral research and teaching and the American Society of Mammalogy guidelines 2011 [67], and was approved by the Ethical Review of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology.

Raccoons are predominantly nocturnal and positional fixes could not be obtained when they were resting in their subterranean dens, registering an error code. Therefore, as well as testing a sampling interval regime (regime 1) that took a fix every hour throughout the 24 h period, including inactive periods when raccoons were denning/undetectable (applied to raccoons B1 and B2), we also programmed a proportion of devices to take a fix every 30 min (regime 2) (applied to raccoons F1, M1, M2, M3, M4) while raccoons were active/detectable at night. These were scheduled to operate from 1 h prior to sunset to 1 h after sunrise. Projecting from the battery capacity, we anticipated that collars should last for up to 90 days under both regimes [28].

System functionality

Positional information collected by CTG collars was sent to an internet carrier server using the FOMA network. These data could then be browsed using a local website service (‘The Location’ Inc.—Tokyo, Japan: e-Location System) (Fig. 5)—either on request by the user, or by setting a scheduled download. This basic website service only provided the location of the CTG device on a base map, which necessitated that we develop a file transfer protocol (FTP) to download these data in an archivable file format, enabling subsequent analysis.

Summary of the location information system used by CTG. The system is divided into three sections: location server, mobile phone network, GPS satellites, and device. Location data which are fixed by GPS positioning or mobile phone network are uploaded to the location information center. Operators need to access the location server to acquire the stored location date or a current location data

At the pre-set fix interval, the FOMA network’s e-Location system ordered a position that the GPS receiver, embedded in the CTG chipset, would try to deliver via the integral FOMA transmitter. In instances where GPS satellite signals could not provide a positional fix for a point in an individual’s movement trajectory (e.g., due to interference/obstruction), CTG stepped in automatically to triangulate location from FOMA base station antennae in relation to the directivity (i.e., the power density radiated by an antenna) of the GPS referenced base station within range (up to three stations). CTG positions were then uploaded automatically by the e-Location server via FOMA network, with no data stored onboard the collar. FOMA stations gave good coverage across this urban area, with potential to allow very accurate positioning, complementing GPS, although it was anticipated that error might be greater with fewer antennae at the suburban margins of this area.

In addition to longitude and latitude, the system also reported three useful error codes:

-

1.

Error details: “Out of signal, Power Off” or “Unable to transmit to GPS-D”, indicating GPS positioning failures and FOMA triangulation failures, or failures in transmission.

-

2.

Expected error tolerance range: “Within 50 m, within 100 m, within 300 m, within 500 m, or over 500 m”.

-

3.

Actual error range (m) from 8 to 4100 m.

Home range analysis

Currently, kernel density estimation (KDE [47]) is one of the most widely used estimators in ecological research [52]. KDE benefits from being statistically efficient, without making any assumptions about the underlying distribution of data [47]. To obtain a home range estimate, KDE places small kernels of bandwidth h at each sampled location, and the average of these kernels provides an estimate of the underlying probability density function (PDF [73]). The value of h is crucial, and is selected to minimize the mean integrated squared error between the true PDF and its estimate [47]. Nevertheless, KDE also has limitations: for instance, the accuracy of the home range estimate is heavily influenced by the choice of the bandwidth optimizer applied (e.g., [53]). More importantly, all conventional KDE bandwidth optimizers (e.g., Gaussian reference function, href, or least-squares cross-validation, hlscv) assume data are statistically independent, and when data exhibit a high degree of autocorrelation, home range areas are significantly underestimated [47, 55]. Because tracking data obtained by modern GPS devices, including the cell phone-based method employed here, have short fix intervals, they typically exhibit substantial autocorrelation [48]. Consequently, home range estimation using conventional KDE bandwidth optimization was invalid here [55]. We therefore applied autocorrelated KDE (AKDE [47]) home range analysis, which can account for the autocorrelation structure inherent in tracking data [47,48,49].

For each individual, we estimated the 95% home range area using AKDE. AKDE is a generalization of conventional Gaussian reference function KDE [47] that operates under the principle that animal movement generally exhibits two distinctive features: (i) autocorrelated positions and/or velocity; and (ii) a tendency to remain in a relatively consistent area (i.e., the ‘home range’ [48]). These features can be identified by variogram analysis, which plots the semi-variance in positions as a function of the time lag separating observations [54], and can be used to classify continuous time stochastic process movement models. Specifically, the variogram of a range resident individual should show a clear asymptote, indicating asymptotic space use over time. The lack of a clear asymptote would suggest that either (i) the animal did not exhibit range resident behavior; or, crucially for this proof-of-concept application (ii) the range resident animal had not been tracked for a sufficient duration. Models containing these features can then be fitted to data using non-Markovian maximum likelihood estimation [74]. The autocorrelation structure of these models can then be used to inform the bandwidth optimization [47]. Modeling the movement process in this way also allowed for information on positional error and irregular sampling regimes to be incorporated into home range estimates.

Following the workflow described by Calabrese et al. [48], we fitted movement models to our relocation data via maximum likelihood, and the best fit model was selected based on AICc. Home ranges were then estimated conditional on the selected model for each individual, using the autocorrelated Gaussian reference function bandwidth relations developed by Fleming et al. [47], and implemented in the R package ctmm [48]. Notably, fitting movement models to relocation data also provides an estimate of the home range crossing time [48]. Furthermore, the information content of a tracking dataset is a function of both the duration of the observation period, and the time it takes an individual to cover its range [47]. As such, an increase in the sampling rate, duration, or number of fixes does not necessarily result in a proportional increase in the effective sample size (neffective [55]). Therefore, we calculated the effective sample size of each dataset following Fleming and Calabrese [49] as the estimated number of range crossing events observed during the observation period. We then used these effective sample sizes as indicators of the data quality returned from CTG tracking.

Importantly however, all of the previous works on the space use of urban raccoons have involved conventional home range estimation with unmodeled autocorrelation [61, 75, 76]. To enable a more complete comparison of our novel data to the results of other studies, using alternative tracking technology, we also applied conventional KDE analysis with the Gaussian reference function bandwidth relationship [74] despite being invalid for these autocorrelated data. For this, we used the KDE method implemented in the R package ctmm [48], again following the workflow described by Calabrese et al. [48].

Availability of data and materials

All data used will be uploaded to the Dryad data repository, upon acceptance.

Abbreviations

- AKDE:

-

Autocorrelated kernel density estimation

- CTG:

-

CTG-001G positional informational terminal

- FOMA:

-

Freedom of Mobile Multimedia Access

- GPS:

-

Global positioning system

- HR:

-

Home range

- KDE:

-

Kernel density estimation

References

Venter O, Brodeur NN, Nemiroff L, Belland B, Dolinsek IJ, Grant JWA. Threats to endangered species in Canada. Bioscience. 2006;56:903–10.

Adams CE. Urban wildlife management. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016.

DeStefano S, DeGraaf RM. Exploring the ecology of suburban wildlife. Front Ecol Environ. 2003;1:95–101.

Beckman JP, Lackey CW. Carnivores, urban landscapes, and longitudinal studies: a case history of black bears. Hum-Wildl Conflicts. 2008;2:77–83.

Gehrt SD, Brown JL, Anchor C. Is the urban coyote a misanthropic synanthrope? The case from Chicago. CATE. 2011;4:3.

Péron G, Fleming CH, de Paula RC, Mitchell N, Strohbach M, Leimgruber P, Calabrese JM. Periodic continuous-time movement models uncover behavioral changes of wild canids along anthropization gradients. Ecol Monogr. 2017;87:442–56.

McKinney ML. Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation. Bioscience. 2002;52:883–90.

Bateman PW, Fleming PA. Big city life: carnivores in urban environments. J Zool. 2012;287:1–23.

Don Carlos AW, Bright AD, Teel TL, Vaske JJ. Human–black bear conflict in urban areas: an integrated approach to management response. Hum Dim Wild. 2009;14:174–84.

Athreya V, Odden M, Linnell JD, Karanth KU. Translocation as a tool for mitigating conflict with leopards in human-dominated landscapes of India. Cons Biol. 2011;25:133–41.

Madden F. Creating coexistence between humans and wildlife: global perspectives on local efforts to address human–wildlife conflict. Hum Dim Wild. 2004;9:247–57.

Stohlgren TJ, Schnase JL. Risk analysis for biological hazards: what we need to know about invasive species. Risk Anal. 2006;26:163–73.

Mackenstedt U, Jenkins D, Romig T. The role of wildlife in the transmission of parasitic zoonoses in peri-urban and urban areas. Int J Parasitol. 2015;4:71–9.

Newman C, Byrne A. Musteloid diseases—implications for conservation and species management. In: Macdonald DW, Newman C, Harrington L, editors. Biology and conservation of musteloids. Oxford: OUP; 2017.

Soulé ME. Land use planning and wildlife maintenance: guidelines for conserving wildlife in an urban landscape. J Am Plann Assoc. 1991;57:313–23.

White PC, Ward AI. Interdisciplinary approaches for the management of existing and emerging human–wildlife conflicts. Wildlife Res. 2011;37:623–9.

Savard JPL, Clergeau P, Mennechez G. Biodiversity concepts and urban ecosystems. Landsc Urban Plan. 2000;48:131–42.

Markovchick-Nicholls L, Regan HM, Deutschman DH, Widyanata A, Martin B, Noreke L, Hunt TA. Relationships between human disturbance and wildlife land use in urban habitat fragments. Conserv Biol. 2008;22:99–109.

Gerber BD, Hooten MB, Peck CP, Rice MB, Gammonley JH, Apa AD, Davis AJ. Accounting for location uncertainty in azimuthal telemetry data improves ecological inference. Move Ecol. 2018;6:14.

Takeuchi T, Matsuki R, Nashimoto M. GPS cell phone tracking in the Greater Tokyo Area: a field test on raccoon dogs. Urban Ecosyst. 2011;15:181–93.

Hebblewhite M, Haydon DT. Distinguishing technology from biology: a critical review of the use of GPS telemetry data in ecology. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:2303–12.

Frair JL, Fieberg J, Hebblewhite M, Cagnacci F, DeCesare NJ, Pedrotti L. Resolving issues of imprecise and habitat-biased locations in ecological analyses using GPS telemetry data. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:2187–200.

Ellwood SA, Newman C, Montgomery RA, Nicosia V, Buesching CD, Markham A, Cecilia M, Trigoni N, Pasztor B, Dyo V, Latora V, Baker SE, Macdonald DW. An active-radio-frequency-identification system capable of identifying co-locations and social-structure: validation with a wild free-ranging animal. Methods Ecol Evol. 2017;8:1822–31.

Ellwood SA, Wilson RP, Addison AC. Technology in conservation: a boon but with small print. In: Macdonald D, Service K, editors. Key topics in conservation biology. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007. p. 105–19.

Tomkiewicz SM, Fuller MR, Kie JG, Bates KK. Global positioning system and associated technologies in animal behavior and ecological research. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2010;B365:2163–76.

Clark PE, Johnson DE, Kniep MA, Jermann P, Huttash B, Wood A, Titus K. An advanced, low-cost, GPS-based animal tracking system. Rangeland Ecol Manag. 2006;59:334–40.

Saeki M, Saito M, Sonoda Y. Application of the commercial location information system on animal tracking. Mammal Sci. 2009;49:277–82.

Yamazaki K, Saeki M. Feasibility of a commercial location information system with GPS mobile phones on raccoons. Mammal Sci. 2012;52:47–54.

Morishita E, Itao K, Sasaki K, Higuchi H. Movements of Jungle Crows in Urban Areas, Based on PHS Tracking. Global Env Res. 2003;7:181–91.

Yamazaki K, Saeki M. Pilot study of Raccoon pest control for minimizing impact on local ecosystem and a survey of distribution and settlement of raccoons around Kasumigaura-lake and Tone-river system. Report River Environ Fund Project Number. 2011;22:1215.

Yanagihara-Agetsuma Y. Process of establishing an introduced raccoon (Procyon lotor) population in Aichi and Gifu Prefectures, Japan: policy for managing threats posed by introduced raccoons. Mammal Sci. 2004;44:147–60.

Ikeda T, Abe G. Population monitoring and evaluation of raccoon control campaign in Hokkaido, Japan. In: Abstract book for the International symposium on control strategy of invasive alien mammals; 2008. p. 59.

Ministry of the Environment of Japan. Current distribution survey result of common raccoon, masked palm civet and nutria. Tokyo: Ministry of the Environment of Japan; 2018. https://www.env.go.jp/press/105902.html. Accessed 10 Oct 2018.

Hayama H, Kaneda M, Tabata M. Rapid range expansion of the feral raccoon (Procyon lotor) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, and its impact on native organisms. In: Norman CM, Maj DP, Iwatsuki K, Kawamichi M, Koike F, editors. Assessment and control of biological invasion risks. Kyoto: Shoukadoh Book Sellers and Gland: IUCN; 2006. p. 196–9.

Machida N, Kiryu K, Oh-Ishi K, Kanda E, Izumisawa N, Nakamura T. Pathology and epidemiology of canine distemper in raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides). J Comp Pathol. 1993;108:383–92.

Sato H, Suzuki K, Osanai A, Kamiya H, Furuoka H. Identification and characterization of the threadworm, Strongyloides procyonis, from feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Japan. J Parasitol. 2006;92:63–8.

Sato H, Suzuki K. Gastrointestinal helminths of feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Wakayama Prefecture. Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2006;68:311–8.

Ninomiya H, Ogata M. Notoedric mange in two free-ranging North American racoons (Procyon lotor) in Japan. Vet Dermatol. 2002;13:119–21.

Kido N, Kamegaya C, Omiya T, Wada Y, Takahashi M, Yamamoto Y. Hematology and serum biochemistry in debilitated, free-ranging raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) infested with sarcoptic mange. Parasitol Int. 2011;60:425–8.

Miyashita M. Prevalence of Baylisascaris procyonis in raccoons in Japan and experimental infections of the worm to laboratory animals. SEIKATSU EISEI (J Urban Liv Health Assoc). 1993;37:137–51.

Sato H, Une Y, Kawakami S, Saito E, Kamiya H, Akao N, Furuoka H. Fatal Baylisascaris larva migrans in a colony of Japanese macaques kept by a safari-style zoo in Japan. J Parasitol. 2005;91:716–20.

Wise ME, Sorvillo FJ, Shafir SC, Ash LR, Berlin OG. Severe and fatal central nervous system disease in humans caused by Baylisascaris procyonis, the common roundworm of raccoons: a review of current literature. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:317–23.

Ikeda T, Asano M, Matoba Y, Abe G. Present status of invasive alien raccoon and its impact in Japan. Global Env Res. 2004;8:125–31.

Ibaraki Prefectural Government. The Second Common raccoon extermination plan in Ibaraki Prefecture. Mito: Ibaraki Prefectural Government; 2016. https://www.pref.ibaraki.jp/seikatsukankyo/kansei/chojyuhogo/documents/araiguma-boujo-20160418p5.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Ministry of the Environment of Japan. Statistics on Wildlife 1998–2015. Tokyo: Ministry of the Environment of Japan; 2018. https://www.env.go.jp/nature/choju/docs/docs2.html. Accessed Oct 2018.

Burt WH. Territoriality and home range concepts as applied to mammals. J Mammal. 1943;24:346–52.

Fleming CH, Fagan WF, Mueller T, Olson KA, Leimgruber P, Calabrese JM. Rigorous home range estimation with movement data: a new autocorrelated kernel density estimator. Ecology. 2015;96:1182–8.

Calabrese JM, Fleming CH, Gurarie E. ctmm: an r package for analyzing animal relocation data as a continuous-time stochastic process. Methods Ecol Evol. 2016;7(9):1124–32.

Fleming CH, Calabrese JM. A new kernel-density estimator for accurate home-range and species-range area estimation. Methods Ecol Evol. 2017;8:571–9.

Worton BJ. Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home-range studies. Ecology. 1989;70:164–8.

Nitta N, Wu F, Lee JT, Yushin G. Li-ion battery materials: present and future. Mater Today. 2015;18:252–64.

Laver PN, Kelly MJ. A critical review of home range studies. J Wildlife Manage. 2008;72:290–8.

Hemson G, Johnson P, South A, Kenward R, Pipley R, Macdonald D. Are kernels the mustard? Data from global positioning system (GPS) collars suggests problems for kernel home-range analyses with least-squares cross-validation. J Anim Ecol. 2005;74:455–63.

Fleming CH, Calabrese JM, Mueller T, Olson KA, Leimgruber P, Fagan WF. From fine-scale foraging to home ranges: a semivariance approach to identifying movement modes across spatiotemporal scales. Am Nat. 2014;183:154–67.

Noonan MJ, Tucker MA, Fleming CH, Akre TS, Alberts SC, Ali AH, Altmann J, Antunes PC, Belant JL, Beyer D, Blaum N, Böhning-Gaese K, Cullen L Jr, de Paula RC, Dekker J, Drescher-Lehman J, Farwig N, Fichtel C, Fischer C, Ford A, Goheen J, Janssen R, Jeltsch F, Kauffman M, Kappeler P, Koch F, LaPoint S, Markham A, Medici EP, Morato RG, Nathan R, Oliveira-Santos L, Olson K, Patterson B, Paviolo A, Ramalho E, Roesner S, Schabo D, Selva N, Sergiel A, da Silva M, Spiegel O, Thompson P, Ullmann W, Zięba F, Zwijacz-Kozica T, Fagan W, Mueller T, Calabrese J. A comprehensive analysis of autocorrelation and bias in home range estimation. Ecol Monog. 2018;89:e01344.

Suzuki T, Aoi T, Maekawa K. Spacing pattern of introduced female raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Hokkaido, Japan. Mammal Study. 2003;28:121–8.

Kurashima O, Niwase N. Spacing pattern of feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) in Eniwa, Hokkaido. Mammal Sci. 1998;38:9–22.

Abe G, Tatsuzawa S. Differences in habitat use of the native raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides albus) and the invasive alien raccoon (Procyon lotor) in the Nopporo Natural Forest Park, Hokkaido, Japan. In: Norman CM, Maj DP, Iwatsuki K, Kawamichi M, Koike F, editors. Assessment and control of biological invasion risks. Kyoto: Shoukadoh Book Sellers and Gland: IUCN; 2006. p. 116–21.

Macdonald DW, Johnson DDP. Patchwork planet: the resource dispersion hypothesis, society, and the ecology of life. J Zool. 2015;295:75–107.

Graser WH, Gehrt SD, Hungerford LL, Anchor C. Variation in demographic patterns and population structure of raccoons across an urban landscape. J Wildlife Manage. 2012;76:976–86.

Prange S, Gehrt SD, Wiggers EP. Influences of anthropogenic resources on raccoon (Procyon lotor) movements and spatial distribution. J Mammal. 2004;85:483–90.

Macdonald DW. Animal behaviour and its role in carnivore conservation: examples of seven deadly threats. Anim Behav. 2016;120:197–209.

Gehrt SD, Seth PD, Cypher CL. Urban carnivores: ecology, conflict, and conservation. Baltimore: JHU Press; 2010.

Ibaraki Prefectural Government. Common raccoon extermination plan in Ibaraki Prefecture. Mito: Ibaraki Prefectural Government; 2010.

Yamazaki K, Saeki M, Takeuchi M, Oikawa H. The present status of the raccoon, an alien mammal, and its control in Ibaraki Prefecture, Central Japan. Bull Ibaraki Nat Museum. 2009;12:41–9.

Yamazaki K, Saeki M. Modified cage trap for removing raccoons to avoid capturing native species in Ibaraki Prefecture, Central Japan. Bull Ibaraki Nat Museum. 2010;13:65–70.

Sikes RS, Gannon WL. The Animal Care and Use Committee of The American Society of Mammalogists. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. J Mammal. 2011;92:235–53.

Aldrige HDJN, Brigham RM. Load carrying and manoeuvrability in an insectivorous bat: a test of the 5% “rule” of radio-telemetry. J Mammal. 1988;69:379–82.

Mech LD, Barnes DM, Tester JR. Seasonal weight changes, mortality, and population structure of raccoons in Minnesota. J Mammal. 1968;49:63–73.

Withey JC, Bloxton TD, Marzluff JM. Effects of tagging and location error in wildlife radiotelemetry studies. In: Millspaugh JJ, Marzluff JM, editors. Radio tracking and animal populations. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2001. p. 52–3.

Gunther I, Finkler H, Terkel J. Demographic differences between urban feeding groups of neutered and sexually intact free-roaming cats following a trap-neuter-return procedure. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;238:1134–40.

Treves A, Karanth KU. Human-carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conserv Biol. 2003;17:1491–9.

Silverman BW. Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1986. p. 176.

Fleming CH, Calabrese JM, Mueller T, Olson KA, Leimgruber P, Fagan WF. Non-Markovian maximum likelihood estimation of autocorrelated movement processes. Methods Ecol Evol. 2014;5:462–72.

Bozek CK, Prange S, Gehrt SD. The influence of anthropogenic resources on multi-scale habitat selection by raccoons. Urban Ecosyst. 2007;10:413–25.

Gross J, Elvinger F, Hungerford LL, Gehrt SD. Raccoon use of the urban matrix in the Baltimore Metropolitan Area, Maryland. Urban Ecosyst. 2012;15:667–82.

Acknowledgements

We thank Midori Saeki, Masahiko Takeuchi, Nachika Ochiai, Hiroko Igarashi, Mayumi Furuya, Yuumi Torii and Akio Iwashita. This research was partly funded by the River Foundation. The work was also partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Nos. 22405003 and 26257404) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. MJN was supported by a Smithsonian Institution CGPS grant, and a US NSF Advances in Biological Informatics grant (ABI-1458748). CDB was supported by a Poleberry Foundation fellowship.

Funding

The work was also partly supported to YK by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Nos. 22405003 and 26257404) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. MJN was supported by a Smithsonian Institution CGPS grant, and a US NSF Advances in Biological Informatics grant (ABI-1458748). CDB was supported by a Poleberry Foundation fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HI led the study and conducted fieldwork with KY. MN contributed to data analysis. CN and CDB contributed to background and manuscript writing. YK oversaw and supervised the project and the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All trapping and handling procedures conformed with the Ethical Review procedures of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, and the Association for the Study of Animal Behavior (2011) guidelines for the treatment of animals in behavioral research and teaching, and the American Society of Mammalogy guidelines [67].

Consent for publication

All authors provided consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishii, H., Yamazaki, K., Noonan, M.J. et al. Testing cellular phone-enhanced GPS tracking technology for urban carnivores. Anim Biotelemetry 7, 19 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-019-0180-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-019-0180-8