Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are common among individuals with human immune deficiency virus (HIV) infection worldwide. In this study, we did a systematic review and meta-analysis of the published literature to estimate the global and regional prevalence of HCV, HBV and HIV coinfections among HIV-positive prisoners.

Methods

We searched PubMed via MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, and Web of science (ISI) to identify studies that reported the prevalence of HBV and HCV among prisoners living with HIV. We used an eight-item checklist for critically appraisal studies of prevalence/incidence of a health problem to assess the quality of publications in the included 48 cross-sectional and 4 cohort studies. We used random-effect models and meta-regression for the meta-analysis of the results of the included studies.

Results

The number of the included studies were 50 for HCV-HIV, and 23 for HBV-HIV co-infections. The pooled prevalence rates of the coinfections were 12% [95% confidence interval (CI) 9.0–16.0] for HBV-HIV and 62% (95% CI 53.0–71.0) for HCV-HIV. Among HIV-positive prisoners who reported drug injection, the prevalence of HBV increased to 15% (95% CI 5.0–23.0), and the HCV prevalence increased to 78% (95% CI 51.0–100). The prevalence of HBV-HIV coinfection among prisoners ranged from 3% in the East Mediterranean region to 27% in the American region. Also, the prevalence of HCV-HIV coinfections among prisoners ranged from 6% in Europe to 98% in the East Mediterranean regions.

Conclusions

Our findings suggested that the high prevalence of HBV and HCV co-infection among HIV-positive prisoners, particularly among those with a history of drug injection, varies significantly across the globe. The results of Meta-regression analysis showed a sliding increase in the prevalence of the studied co-infections among prisoners over the past decades, rising a call for better screening and treatment programs targeting this high-risk population. To prevent the above coinfections among prisoners, aimed public health services (e.g. harm reduction via access to clean needles), human rights, equity, and ethics are to be seriously delivered or practiced in prisons.

Protocol registration number: CRD42018115707 (in the PROSPERO international).

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections are major health problems with considerable morbidity and mortality due to serious complications [1]. This issue is even more serious among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected individuals [2, 3]. The co-infections may accelerate the disease progression and raise the risk of severe liver diseases or mortality, and also cause complications in the treatment of HIV and hepatitis coinfection [4]. The global prevalence rates of HCV and HBV infections among HIV-positive individuals are estimated to be 2.4% and 7.6% respectively [2, 5].

Among different segments of a population, prisoners are at a higher risk of HIV, HCV, and HBV infections due to risky behaviors such as drug use and high-risk sexual practices [6, 7]. A review of literature from 2005 to 2015 among prisoners showed that the global prevalence of HIV, HCV, and HBV in prisoners are about 3.8%, 15.1%, and 4.8% respectively [6]. The highest prevalence of HIV/HCV co-infection was reported for people who inject drugs (PWID) followed by men who have sex with men (MSM) [8]. The prevalence of HIV was the highest among prisoners in sub-Saharan Africa, in Europe, and central Asia respectively [8, 9]. The highest HBV prevalence among prisoners was reported from West and Central Africa [8]. The reports also suggested a high variation in the prevalence of HIV and viral hepatitis infections among prisoners worldwide.

Prisons provide both challenges and opportunities to HIV and viral hepatitis control programs. If effective control measures are not applied in the prisons, these places can become a place for further spread of the above infections among prisoners, to their family, and a wider community upon their release [9]. The previous outbreaks of HIV, HCV and other infections in prison settings highlight the importance of the above issue [8]. On the other hand, prisons can provide valuable opportunities regarding the diagnosis and treatment of health conditions such as the screening of HIV, HCV, and HBV that would have not otherwise been detected in such high-risk minority populations. An example of successful intervention programs targeting the above infections among prisoners is the “community-based needle and syringe programs” in Australia [10]. Australia’s HIV infection prevalence of almost zero in people who inject drugs in and out of prison can be traced back to the introduction of the programs in 1986, which prevented an estimated 25 000 cases of HIV in people who inject drugs [11].

Despite the fact that the prevalence of blood-borne hepatitis viruses and HIV is expected to be very high in correctional facilities around the world [12], only a few regional studies assessed the prevalence of these infections in these centers [11,12,13]. Moreover, limited evidence are available on the global status of HCV and HBV coinfection among HIV-positive prisoners. To address this important issue, we did a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the published literature to estimate the global and regional prevalence of HCV, HBV and HIV coinfections among the above mentioned high-risk population.

Methods

Protocol and registration

We designed our systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist [14] and PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) standards [15, 16], under a registered protocol (registration number CRD42018115707) [17].

Search strategy and selection criteria

We did a comprehensive systematic search of the literature to find cross-sectional and cohort studies that investigated the prevalence and incidence of HCV or HBV in prisoners living with HIV. We searched PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, the Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, and Web of science (ISI) databases by combining three sets of related MeSH and Non-MeSH terms: (1) “hepatitis B” OR “HBV” OR “hepatitis C” OR “HCV”, (2) “HIV”, “AIDS”, “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” and (3) “prison* OR concentration camps OR incarcerate* OR penitentiar* OR jail to find relevant studies that were published until December 2020, with no limitation regarding language.

Studies were eligible for our review if they met the following criteria (1) original studies with cohort or cross-sectional designs; (2) study that recruited prisoners, and (3) studied that diagnosed HIV, HCV, and HBV infections with standard laboratory tests. Three authors independently reviewed the studies and discrepancies were resolved by discussing with the fourth author. The references of eligible articles were also manually reviewed for other possibly related articles that were not found in the electronic search.

Quality assessment

The eight-item checklist for critically appraisal studies of prevalence/incidence of health problems [16] was used to examine the quality of eligible studies by two independent investigators (HA and JR). The range of the total score was from 0 (the lowest possible quality) to 8 (the highest possible quality); the details of this tool are provided in the Additional file 1. The quality of the studies is categorized as high (score ≥ 7), medium (score between 4 and 6), or low (score < 4).

Data extraction

Two of the co-authors independently extracted the following data from included studies; author’s name, study year, study design, country and region, mean age of the participants, the number of prisons, the total number of prisoners who had HIV infection, and the frequency and prevalence of HCV or HBV in those prisoners living with HIV. The extracted data were compared and the reviewers discussed discrepancies to reach a consensus. If the full text of a study was unavailable or if the reported data was missing key information, we contacted the authors by email at least twice, one week apart. In case that we did not hear from the authors, we sent an email to the publishers (e.g. Elsevier or Wiley Online Library) to help.

Statistical analysis

The number of individuals with HCV or HBV infections in prisoners living with HIV and the total number of prisoners living with HIV were used to calculate the prevalence of coinfection (in logit form) and its corresponding standard error (SE). The summary prevalence with 95% CI was obtained using a random-effects model. Cochran’s Q test was used to identify the heterogeneity of the results, and it was quantified using the I2 statistic. I2 statistic > 50% or Q statistics with P < 0.10 were considered as a significant between-study heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis based on the region of the study was performed to explore possible sources of heterogeneity. A meta-regression analysis was conducted to explore the association between the study year and the difference in HCV or HBV prevalence among prisoners living with HIV. A jack-knife sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing the studies from meta-analyses one by one. We also evaluated the publication bias using Begg's funnel plots and the asymmetry tests (Egger's and Begg's test). We further used free World Shapefiles to design maps (available at: https://tapiquen-sig.jimdofree.com/english-version/free-downloads/world/) using ArcGIS software (ArcGIS 10.2.2. Esri. 2014-02-27). All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.). P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

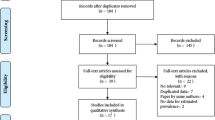

A total of 4022 records were obtained by electronic and manual search (Fig. 1). After removing duplicate records, 2562 records remained for further assessment. We excluded 2057 studies after screening titles and/or abstracts. We read 505 studies and during the full-text review, 453 articles were excluded for different reasons (Fig. 1). In the end, 52 eligible articles were included in our qualitative synthesis and the quantitative meta-analysis [6, 7, 9, 19–31, 33, 35–59, 61–66]. The characteristics of the studies included in this review are presented in Table 1.

Of the 52 included studies, 48 were cross-sectional [6, 7, 9, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31, 33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, 61,62,63,64,65,66] and 4 were prospective cohort studies [10, 32, 34, 60]. Of all, 50 studies reported HCV infection [6, 7, 9, 10, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, 65] and 23 studies reported either solely HBV infection or both HBV and HCV infections [19, 21, 25, 28, 32, 34,35,36,37, 41, 43,44,45,46, 52, 54,55,56, 58, 60, 64,65,66]. Regarding the study location, 21 studies were conducted in Europe [9, 10, 21, 24, 25, 27, 33, 34, 39, 42, 45,46,47, 49, 52, 55, 56, 58, 60, 63, 65], 18 were conducted in America [6, 7, 20, 22, 23, 26, 29,30,31,32, 37, 38, 50, 57, 59, 61, 62, 66], 2 in South-East Asia [41, 48], 7 in East Mediterranean [28, 36, 40, 43, 44, 51, 54], 3 in Western Pacific [19, 35, 53], and 1 in Africa region [64].

Assessment of the studies’ quality

Out of the 52 included studies [6, 7, 9, 10, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], we found 17 studies [9, 10, 19, 22, 28, 33, 37, 39, 43, 44, 46, 47, 53, 54, 56, 58, 66] with high quality, 25 studies with medium quality [6, 7, 20, 21, 23, 24, 29,30,31, 35, 38, 40, 41, 45, 49, 50, 56, 57, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65], and 10 studies with low quality [25,26,27, 32, 34, 36, 42, 48, 51, 52]

HBV infection

Of the 8449 prisoners with HIV recruited in the selected studies, 628 (7.4%) had HBV infection (Table 1). The highest prevalence of HBV infection among HIV positive prisoners was 81% (95% CI 67.0–90.0), which was reported by Rui Passadouro et al. (2004) in Portugal [25] and the lowest prevalence (1%, 95% CI 0.0–6.0) was reported by Nafees (2011) in Pakistan [44].

The overall pooled prevalence of HBV among HIV positive prisoners was 12% (95% CI 9.0–16.0, I2 = 93.8% (P < 0.001). Also, twenty three studies [19, 21, 25, 28, 32, 34,35,36,37, 41, 43,44,45,46, 52, 54,55,56, 58, 60, 64,65,66] reported a 15% prevalence of HBV among HIV-positive prisoners with a history of drug injection (pooled prevalence = 12%, 95% CI 5.0–23.0), with significant heterogeneity in the results I2 = 84.8% (P < 0.001). Subgroup analysis by WHO regions is provided in Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Fig. 1. The regional pooled prevalence rates of HBV among HIV-positive prisoners were 27% in the Western Pacific, 18% in Europe, 15% in African regions, 5% in America, 3% in Eastern Mediterranean, and 3% in Southeast Asia respectively.

The results of sensitivity analysis showed no significant difference between all included studies and studies with low-quality scores. The Egger test (t = 2.59, P-value = 0.01) and funnel plot (Additional file 1: Figs. 2 and 3) indicated a publication bias for studies that reported HBV infection. Also, the results of meta-regression for the prevalence of HBV infection among prisoners living with HIV by the year of publication are provided in Additional file 1: Fig. 4.

HCV infection

Of the 15 721 recruited HIV positive prisoners, 6858 (43%) had HCV infection (Table 1). The highest and the lowest prevalence of HCV/HIV coinfection was reported in Iran (pooled prevalence = 98%, 95% CI 93.0–99.0) [40], and Spain (pooled prevalence = 6%, 95% CI 3.0–11.0) respectively [21].

The overall pooled prevalence of HCV infection from the included studies [6, 7, 9, 10, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, 65] was 62% (95% CI 53.0–71.0, I2 = 95.8%, P < 0.001). The prevalence of HCV infection among HIV-positive prisoners with a history of drug injection was 78% (95% CI 51.0–100) with a significant heterogeneity I2 = 99.8% (P < 0.001).

The pooled prevalence rates of HCV infection among HIV-positive prisoners were 83% in Eastern Mediterranean, 83% in South East Asia, 75% in Western Pacific, 64% in Europe, and 45% in America respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). No study measured HCV/HIV coinfection among prisoners in the African region.

Meta-regression indicated that heterogeneous results in HCV/HIV coinfection can be significantly attributed to the WHO regions (β = −6.8, P = 0.004). No significant association was found for other factors (i.e. study design, study quality, sample size, and years of publication) (Table 2). Results of sensitivity analysis showed no significant difference between all included studies and studies with low-quality scores. Egger test (t = 6.6, P < 0.001) and funnel plot (Additional file 1: Figs. 5 and 6) indicated a publication bias for studies that reported HCV/HIV coinfection. Meta-regression of the association between the prevalence of HCV/HIV coinfection during 1990–2019 in prisoners and year of study is shown in Additional file 1: Fig. 7.

Discussion and conclusion

Our findings indicated that two-third of prisoners living with HIV are infected with HCV and one in ten are infected with HBV. Our results also indicated the hepatitis-HIV co-infection prevalence rates are highly variable across the globe.

In comparison with the prevalence of 7.0% for HBV and 2.4–5% for HCV among HIV positive individuals in the general population [2, 67, 68], we found a much higher prevalence of such co-infections among prisoners living with HIV. Several societal and environmental factors in prisons contribute to the higher transmission of HIV, HBV, and HCV infections among HIV-positive prisoners (these risk factors include population density, tattooing, drug injection, and sexual behaviors) [67, 69]. Also, we found a high prevalence of HIV/HCV co-infection (62%) among prisoners, in comparison to the prevalence of both HIV/HBV and HIV/HCV coinfections in health care workers (31%) [70]. In our study, we found that the prevalence of HCV/HIV co-infection in prosoners was significantly higher compared to high-risk groups in general population; including persons who inject drugs (PWID) (51%) [70] and 6.4% in MSM [71]. A possible justification for a higher rate of HCV than HBV in prisons could be attributed to the route of infection transmission [72]. For example, drug injection with sharing needles and syringes, and tattooing, which are substantially prevalent among prisoners, are strongly associated with transmission of HCV than HBV [72]. Also, using shared syringes and no vaccination for HCV among prisoners make them more prone to the acquisition of HCV than HBV [3]. More studies are needed to fully explain the possible reasons for the higher prevalence of HCV than HBV among prisoners with HIV.

Prisoners are considered as a high-risk group for HIV, HBV, HCV, and other sexually transmitted infections due to the more common risk factors such as drug injection with sharing needles and syringes, tattooing, and unsafe sex relationships. Prisons amplify adverse health conditions through overcrowding, poor infrastructure, and restricted access to healthcare services. Additionally, malnutrition, background infectious diseases, harsh social environment, and practices of some custodial officers toward inmates contribute to the deterioration of the physical and mental health of prisoners after incarceration [68, 73].

The current study found a higher pooled prevalence of HCV among HIV-positive prisoners who inject drugs (78%), a phenomenon mostly attributed to unsafe injection. A meta-analysis of 30 studies showed that prisoners who injected drugs are about 24-times more likely to be HCV infected than those with no history of drug injection [74]. Another study conducted on prisoners showed that HCV infection is the main risk factor associated with HIV infection with an odds ratio of 7.5 [43]. Researchers reported that the prevalence of HCV infection ranges from 22 to 40% among incarcerated populations, and that many prisoners acquire these infections before being incarcerated [75].

Regarding the geographical disparity in the rates of co-infections, the highest pooled prevalence of HCV/HIV co-infection was found in the South East Asia and East Mediterranean regions (83% for both regions) and the lower prevalence in America region (48%). Differences in the prevalence of HCV/HIV co-infection in prisons among different regions can be explained by some cultural, social, behavioral, and demographical differences. For example, more than 80% of the heroin production in the world is produced in Afghanistan, a country located in the East Mediterranean region [76] while injecting drug users (IDUs) is not common in the Caribbean [77]. Likewise, it is reported that, the proportions of in-prison drug injection are varying from 13% in Australia [78] to 61% in Mexico [79]. Results of a systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that behaviors like unsterile tattooing and body piercing, two risky behaviors that are common in prisons, are other sources of in-prison transmission of HIV, HBV, and HCV infections [80]. Also, more than 60% of inmates in Puerto Rican prisons get tattoos in prison with shared needles and unsterilized sharp objects [81].

According to our findings, the prevalence of HBV/HIV co-infection in prisoners has a wide variation from 3% in Eastern Mediterranean and South East Asia, to 27% in the Western Pacific region. The discrepancy between regions in the results of pooled prevalence of HBV/HIV co-infection is also reported among the general population [82] with the highest proportion in the West and Central Africa (12.4%) and the lowest proportion in Latin America and the Caribbean (5.1%). One study reported the prevalence of HBV/HIV as 15% in Africa [64]. However, there is limited data on the HBV/HIV co-infection in the African region, as only about 2% of prisoners are tested for HBV (before or during incarceration) in the region [83]. Also, only 14% of African prisoners have heard about hepatitis before being incarcerated, and HBV screening or vaccination is not a routine procedure in the prisons of this region [83].

Although limited data is available on the frequency and dynamics of risky sexual activities in detention centers and jails, it is suggested that, in the absence of access to condom and lubricants, sex for pleasure or in exchange for drug, money, personal protection, food, or other goods is common in prisons and this risky behavior is even more common among prisoners with HIV [3, 83].

The high prevalence of HBV and HCV among HIV-positive prisoners found in this study is a global alert for the necessity of providing specific and effective interventions in prisons. Guidelines for the implementation of comprehensive evidence-based interventions in prisons have been provided by both WHO and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime [84, 85]. Among some key interventions to prevent the transmission of blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections in prisons, screening and, if possible, vaccination and medical services (e.g. antiretroviral therapy (ART)), surveillance programs, health education, and consultation to prisoners or staff, free and easy access to condom, and lubricants for prisoners are essential. Services in prisons, including vaccination, health education, and screening at the entry of a prisoner, are crucial to diagnose, treat, and prevent the transmission of communicable diseases [85]. Although limmited evidence regarding the effectiveness of HCV and HBV screening among prisoners exist, a systematic review on routine screening for blood-borne viruses in prisons showed that routine opt-in and opt-out screening is both feasible and effective [86]. Although difficulties regarding the implementation of HIV and viral hepatitis screening in prison exist, new achievements in HCV treatment have led to the call for HCV case-finding and treatment for prisoners [87]. Also, for HBV, vaccination of HIV-positive individuals is recommended to reduce the risk of transmission of this infection. This conclusion is also supported by the results of a comprehensive review on this subject [88].

As mentioned before, despite the generally poor sanitary conditions and limited access to disposable syringes, drugs are always available in prisons. Knowing that people who inject drugs comprise about one-third to half of the prisoners and that needles and syringes are expensive to obtain in the prisons, use/reuse of unsafe injecting drug equipment is highly common and prisoners are often forced to share or make their injecting equipment [89]. As a result, there is mounting evidence that one of the most effective ways of preventing the spread of blood-borne infections in prisons is providing harm reduction services such as needle and syringe programmes (NSPs) and opioid substitution therapy (OST) [90]. Yet, the availability of these life-saving services remains extremely limited when compared to what is available in the community. For example, while 90 and 80 countries implement NSPs and OST in their community respectively, only seven and 43 implement these services in at least one of their prisons [91, 89].

Because the vast majority of prisoners will eventually return to the community, the prisoners’ health is intimately connected to public health. As a result, there is no doubt that to reach the WHO’s global targets on the control of HIV, tuberculosis (TB), and HCV, health and harm reduction services in prisons need to be significantly scaled up [89].

We believe, any comprehensive national and international strategy for the prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment of viral hepatitis must include jails and prisons. Immunization of those who are tested negative, treatment of those who are chronically infected, treatment of substance use in correctional facilities, and harm-reduction services can benefit any population by decreasing recidivism, infection transmission, and the costs associated with the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis in the population [92].

This study has some strengths and limitations to be noted. The important procedures such as searching studies, data extraction, and quality assessment were independently performed by two experts. However, there was limited data for some WHO regions in the subgroup analysis. Another limitation to the present study is publication bias, as some regions had more published studies than other regions. Finally, the difference in the HBV and HCV diagnosis methods may influence the estimated prevalence and observed heterogeneity.

In summary, our findings suggested a high prevalence of HBV and HCV coinfections among prisoners living with HIV particularly those with a history of drug injection that varied significantly across different regions. According to the results of the meta-regression, there was no reduction in the prevalence of the studied co-infections over the past decades, which call for better screening and treatment programs targeting prisoners living with HIV. We found that HCV/HIV coinfection was more prevalent than HBV/HIV coinfection in the prisons especially if they were IDUs. The Key action is urgently needed to scale up evidence-based interventions to prevent HIV, HBV, and HCV in prisoners by a broad range of strategies. Cooperation and collaboration will be needed to take place between the governments, justice departments, the prisons’ staff, health-care workers, academics, and NGOs. The findings of the current study are highly valuable for policymakers to design and implement interventional programs among high-risk groups especially prisoners.

Availability of data and materials

The data are presented in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AIDS :

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- ART :

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- CI :

-

Confidence interval

- HIV :

-

Human immune deficiency virus

- HCV :

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HBV :

-

Hepatitis B virus

- IDUs :

-

Injecting drug users

- NSPs :

-

Needle and syringe programmes

- OST :

-

Opioid substitution therapy

- PWID :

-

Persons who inject drugs

- PRISMA :

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- SE :

-

Standard error

- TB :

-

Tuberculosis

References

Leumi S, Bigna JJ, Amougou MA, Ngouo A, Nyaga UF, Noubiap JJ. Global burden of hepatitis B infection in people living with human immunodeficiency virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(11):2799–806.

Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, McDonald B, Sabin K, McGowan C, et al. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):797–808.

Kamarulzaman A, Reid SE, Schwitters A, Wiessing L, El-Bassel N, Dolan K, et al. Prevention of transmission of HIV, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in prisoners. The Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1115–26.

Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Di Martino V, Charlotte F, Azria F, Coutellier A, et al. Liver fibrosis progression in human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus coinfected patients. Hepatology. 1999;30(4):1054–8.

Platt L, French CE, McGowan CR, Sabin K, Gower E, Trickey A, et al. Prevalence and burden of HBV co-infection among people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27(3):294–315.

Alvarez KJ, Befus M, Herzig CTA, Larson E. Prevalence and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among inmates at two New York State correctional facilities. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7(6):517–21.

Baillargeon J, Pulvino JS, Leonardson JE, Linthicum LC, Williams B, Penn J, et al. The changing epidemiology of HIV in the criminal justice system. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(13):1335–40.

Dolan K, Wirtz AL, Moazen B, Ndeffo-mbah M, Galvani A, Kinner SA, et al. Global burden of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in prisoners and detainees. The Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1089–102.

Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Grishaev Y, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Burden of infectious diseases, substance use disorders, and mental illness among Ukrainian prisoners transitioning to the community. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59643.

Marco A, Gallego C, Cayla JA. Incidence of hepatitis C infection among prisoners by routine laboratory values during a 20-year period. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e90560.

International HO. Return on investment in needle and syringe programs in Australia. Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing Canberra (https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/needle-return); 2002.

Tresó B, Barcsay E, Tarján A, Horváth G, Dencs A, Hettmann A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HCV, HVB, and HIV infection among prison inmates and staff. Hungary J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):108–16.

Stanekova D, Ondrejka D, Habekova M, Wimmerova S, Kucerkova S. Pilot study of risk behaviour, voluntary HIV counselling and HIV antibody testing from saliva among inmates of prisons in Slovakia. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2001;9(2):87–90.

Burek V, Horvat J, Butorac K, Mikulic R. Viral hepatitis B, C and HIV infection in Croatian prisons. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(11):1610–20.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Dianatinasab M RJ, Ahmadi H, Fararouei M. Prevalence of HBV and HCV in HIV/AIDS infected prisoners: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. CRD42018115707, 2019. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=115707.

Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, Roberts JG, Stratford PW. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. 1998;19(4):170–6.

Butler TG, Dolan KA, Ferson MJ, McGuinness LM, Brown PR, Robertson PW. Hepatitis B and C in New South Wales prisons: prevalence and risk factors. Med J Aust. 1997;166(3):127–30.

Massad E, Rozman M, Azevedo RS, Silveira AS, Takey K, Yamamoto YI, et al. Seroprevalence of HIV, HCV and syphilis in Brazilian prisoners: preponderance of parenteral transmission. Eur J Epid. 1999;15(5):439–45.

Pallas JR, Farinas-Alvarez C, Prieto D, Delgado-Rodriguez M. Coinfections by HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C in imprisoned injecting drug users. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15(8):699–704.

Guimarães T, Granato CF, Varella D, Ferraz ML, Castelo A, Kallás EG. High prevalence of hepatitis C infection in a Brazilian prison: identification of risk factors for infection. Braz J Infect Dis. 2001;5(3):111–8.

Baillargeon J, Wu H, Kelley MJ, Grady J, Linthicum L, Dunn K. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among newly incarcerated inmates in the Texas correctional system. Public Health. 2003;117(1):43–8.

Quaglio G, Lugoboni F, Pajusco B, Sarti M, Talamini G, Lechi A, et al. Factors associated with hepatitis C virus infection in injection and noninjection drug users in Italy. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(1):33–40.

Passadouro R. Prevalence infections and risk factors due to HIV, Hepatitis B and C in a prison establishment in Leiria. Acta Med Port. 2004;17(5):381–4.

Solomon L, Flynn C, Muck K, Vertefeuille J. Prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among entrants to Maryland correctional facilities. J Urban Health. 2004;81(1):25–37.

Saiz de la Hoya P, Bedia M, Murcia J, Cebria J, Sanchez-Paya J, Portilla J. Predictive markers of HIV and HCV infection and co-infection among inmates in a Spanish prison. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiologia Clinica. 2005;23(2):53–7.

Khodabakhshi B, Abbassi A, Fadaee F, Rabiee M. Prevalence and risk factors of HIV, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections in drug addicts among Gorgan prisoners. J Med Sci. 2007;7(2):252–4.

Calzavara L, Ramuscak N, Burchell AN, Swantee C, Myers T, Ford P, et al. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections among inmates of Ontario remand facilities. CMAJ. 2007;177(3):257–61.

Poulin C, Alary M, Lambert G, Godin G, Landry S, Gagnon H, et al. Prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections among inmates of Quebec provincial prisons. CMAJ. 2007;177(3):252–6.

Vlahov D, Nelson KE, Quinn TC, Kendig N. Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among male prison inmates in Maryland. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9(5):566–9.

Baillargeon JG, Paar DP, Wu H, Giordano TP, Murray O, Raimer BG, et al. Psychiatric disorders, HIV infection and HEV/hepatitis cc-infection in the correctional setting. AIDS Care. 2008;20(1):124–9.

Barros H, Ramos E, Lucas R. A survey of HIV and HCV among female prison inmates in Portugal. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2008;16(3):116–20.

Pontali E, Ferrari F. Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus and/or hepatitis C virus co-infections in prisoners infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Prison Health. 2008;4(2):77–82.

Chu FY, Chiang SC, Su FH, Chang YY, Cheng SH. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and its association with hepatitis B, C, and D virus infections among incarcerated male substance abusers in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 2009;81(6):973–8.

Davoodian P, Dadvand H, Mahoori K, Amoozandeh A, Salavati A. Prevalence of selected sexually and blood-borne infections in injecting drug abuser inmates of Bandar Abbas and Roodan correction facilities, Iran, 2002. Braz J Infect Dis. 2009;13(5):356–8.

Hennessey KA, Kim AA, Griffin V, Collins NT, Weinbaum CM, Sabin K. Prevalence of infection with hepatitis B and C viruses and co-infection with HIV in three jails: a case for viral hepatitis prevention in jails in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(1):93–105.

Rosen DL, Schoenbach VJ, Wohl DA, White BL, Stewart PW, Golin CE. Characteristics and behaviors associated with HIV infection among inmates in the North Carolina Prison System. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1123–30.

Sanchez VM, Caleya JFL, Vasquez MGN, Gonzalez MLM, Vicente RP, Buqueras JAC. HCV and HIV infection, and coinfection in the Leon Health Area in the period 1993–2004. Revista Espanola De Salud Publica. 2009;83(4):533–41.

Hosseini M, SeyedAlinaghi S, Kheirandish P, Esmaeli Javid G, Shirzad H, Karami N, et al. Prevalence and correlates of co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus in male injection drug users in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2010;13(4):318–23.

Nelwan EJ, van Crevel R, Alisjahbana B, Indrati AK, Dwiyana RF, Nuralam N, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and hepatitis C in an Indonesian prison: prevalence, risk factors and implications of HIV screening. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(12):1491–8.

Marques NM, Margalho R, Melo MJ, Cunha JG, Melico-Silvestre AA. Seroepidemiological survey of transmissible infectious diseases in a portuguese prison establishment. Braz J Infect Dis. 2011;15(3):272–5.

Mir-Nasseri MM, Mohammadkhani A, Tavakkoli H, Ansari E, Poustchi H. Incarceration is a major risk factor for blood-borne infection among intravenous drug users: incarceration and blood borne infection among intravenous drug users. Hepat Mon. 2011;11(1):19–22.

Nafees M, Qasim A, Jafferi G, Anwar MS, Muazzam M. HIV Infection, HIV/HCV and HIV/HBV co-infections among jail inmates of Lahore. Pak J Med Sci. 2011;27(4):837–41.

Marco A, Saiz de la Hoya P, García-Guerrero J, Grupo P. Multi-centre study of the prevalence of infection from HIV and associated factors in Spanish prisons. Rev Esp Sanid Penit. 2012;14(1):19–27.

Mouriño AM, Gallego Castellví C, García De Olalla P, Solé Zapata N, Argüelles Fernández MJ, Escribano Ibáñez M, et al. Late diagnosis of HIV infection among prisoners. AIDS Rev. 2013;15(3):146–51.

Brandolini M, Novati S, De Silvestri A, Tinelli C, Patruno SF, Ranieri R, et al. Prevalence and epidemiological correlates and treatment outcome of HCV infection in an Italian prison setting. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:981.

Prasetyo AA, Dirgahayu P, Sari Y, Hudiyono H, Kageyama S. Molecular epidemiology of HIV, HBV, HCV, and HTLV-1/2 in drug abuser inmates in central Javan prisons, Indonesia. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(6):453–67.

Semaille C, Le Strat Y, Chiron E, Chemlal K, Valantin MA, Serre P, et al. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus among French prison inmates in 2010: a challenge for public health policy. Euro Surveill. 2013. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2013.18.28.20524.

Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Rivera-Negron RM, Clatts MC, Myers JJ. Health care practices and associated service needs in a sample of HIV-positive incarcerated men in Puerto Rico: implications for retention in care. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13(6):492–6.

Ruiseñor-Escudero H, Wirtz AL, Berry M, Mfochive-Njindan I, Paikan F, Yousufi HA, et al. Risky behavior and correlates of HIV and hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in three cities in Afghanistan. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;143:127–33.

Chan SY, Marsh K, Lau R, Pakianathan M, Hughes G. An audit of HIV care in English prisons. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(7):504–8.

Bick J, Culbert G, Al-Darraji HA, Koh C, Pillai V, Kamarulzaman A, et al. Healthcare resources are inadequate to address the burden of illness among HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia. Int J Prison Health. 2016;12(4):253–69.

Farhoudi B, SeyedAlinaghi S, Mohraz M, Hosseini M, Farnia M. Tuberculosis, hepatitis C and hepatitis B co-infections in patients with HIV in the Great Tehran Prison, Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;6(1):82–3.

Pontali E, Bobbio N, Zaccardi M, Urciuoli R. Blood-borne viral co-infections among human immunodeficiency virus-infected inmates. Int J Prison Health. 2016;12(2):88–97.

Sanarico N, D’Amato S, Bruni R, Rovetto C, Salvi E, Di Zeo P, et al. Correlates of infection and molecular characterization of blood-borne HIV, HCV, and HBV infections in HIV-1 infected inmates in Italy An observational cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2016;95(44):e5257.

Akiyama MJ, Kaba F, Rosner Z, Alper H, Kopolow A, Litwin AH, et al. Correlates of hepatitis C virus infection in the targeted testing program of the New York city jail system: epidemiologic patterns and priorities for action. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(1):41–7.

Pontali E, Ranieri R, Rastrelli E, Iannece MD, Ialungo AM, Dell’Isola S, et al. Hospital admissions for HIV-infected prisoners in Italy. Int J Prison Health. 2017;13(2):105–12.

De la Flor C, Porsa E, Nijhawan AE. Opt-out HIV and hepatitis C testing at the Dallas County jail: uptake, prevalence, and demographic characteristics of testers. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(6):617–21.

Prestileo T, Spicola D, Di Lorenzo F, Dalle Nogare ER, Sanfilippo A, Ficalora A, et al. Infectious diseases among foreign prisoners: results of a hospital-based management model in Palermo. Infez Med. 2017;25(1):57–63.

Puga MA, Bandeira LM, Pompilio MA, Croda J, Rezende GR, Dorisbor LF, et al. Prevalence and incidence of HCV infection among prisoners in Central Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0169195.

Silverman-Retana O, Serván-Mori E, McCoy SI, Larney S, Bautista-Arredondo S. Hepatitis C antibody prevalence among Mexico City prisoners injecting legal and illegal substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;181:140–5.

Kivimets K, Uuskula A, Lazarus JV, Ott K. Hepatitis C seropositivity among newly incarcerated prisoners in Estonia: data analysis of electronic health records from 2014 to 2015. BMC Infect Dis. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3242-2.

Adoga MP, Banwat EB, Forbi JC, Nimzing L, Pam CR, Gyar SD, et al. Human immunonodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus: sero-prevalence, co-infection and risk factors among prison inmates in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3(7):539–47.

Babudieri S, Longo B, Sarmati L, Starnini G, Dori L, Suligoi B, et al. Correlates of HIV, HBV, and HCV infections in a prison inmate population: results from a multicentre study in Italy. J Med Virol. 2005;76(3):311–7.

Smith PF, Mikl J, Truman BI, Lessner L, Lehman JS, Stevens RW, et al. VI. HIV infection among women entering the New York State Correctional System. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(SUPPL.):35–40.

Tengan FM, Abdala E, Nascimento M, Bernardo WM, Barone AA. Prevalence of hepatitis B in people living with HIV/AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):587.

Ireland G, Delpech V, Kirwan P, Croxford S, Lattimore S, Sabin C, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed HIV infection among persons with hepatitis C virus infection: England, 2008–2014. HIV Med. 2018;19(10):708–15.

Vescio MF, Longo B, Babudieri S, Starnini G, Carbonara S, Rezza G, et al. Correlates of hepatitis C virus seropositivity in prison inmates: a meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(4):305–13.

Amiri FB, Mostafavi E, Mirzazadeh A. HIV, HBV and HCV coinfection prevalence in Iran—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151946.

Ejeta E, Dabsu RJ. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus and HIV infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in Western Ethiopia. Front Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00366.

Tohme RA, Holmberg SD. Transmission of hepatitis C virus infection through tattooing and piercing: a critical review. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):1167–78.

Baybutt M, Chemlal K. Health-promoting prisons: theory to practice. Glob Health Promot. 2016;23(1_suppl):66–74.

Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. The Lancet. 2011;377(9769):956–65.

Burattini M, Massad E, Rozman M, Azevedo R, Carvalho H. Correlation between HIV and HCV in Brazilian prisoners: evidence for parenteral transmission inside prison. Rev Saude Publica. 2000;34(5):431–6.

Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, Krahn MD. Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected individuals and the impact of HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. AIDS (London, England). 2008;22(15):1979–91.

Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD. Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:325–39.

UNODC. World Drug Report 2011. New York: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2011.

Aceijas C, Stimson GV, Hickman M, Rhodes T. Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users. AIDS Res Ther. 2004;18:2295–303.

Kinner SA, Jenkinson R, Gouillou M, Milloy M-J. High-risk drug-use practices among a large sample of Australian prisoners. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126(1–2):156–60.

Pollini RA, Alvelais J, Gallardo M, Vera A, Lozada R, Magis-Rodriquez C, et al. The harm inside: injection during incarceration among male injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103(1–2):52–8.

Peña-Orellana M, Hernández-Viver A, Caraballo-Correa G, Albizu-García CE. Prevalence of HCV risk behaviors among prison inmates: tattooing and injection drug use. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(3):962–82.

Augusto A, Augusto O, Taquibo A, Nhachigule C, Siyawadya N, Gudo ES. High frequency of HBV in HIV-infected prisoners in Mozambique. Int J Prison Health. 2019;15(1):58–65.

Hashiani AA, Sadeghi F, Ayubi E, Rezaeian S, Moradi Y, Mansori K, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B and C virus co-infections among Iranian high-risk groups: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malays J Med Sci. 2019;26(3):37–48.

UNODC I, UNDP W. UNAIDS. HIV prevention, treatment and care in prisons and other closed settings: a comprehensive package of interventions; 2013. https://www.unodc.org/documents/hiv-aids/HIV_comprehensive_package_prison_2013_eBook.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2020.

Europe W, Baybutt M, Ritter C, Stöver H. Prisons and health. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, UNOCD, ICR, Consejo de Europa, Confederación Suiza; 2014. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/249188/Prisons-and-Health.pdf. Accessed 15 Jan 2020

Post JJ, Arain A, Lloyd AR. Enhancing assessment and treatment of hepatitis C in the custodial setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(suppl_2):S70–74.

Rumble C, Pevalin DJ, O’Moore É. Routine testing for blood-borne viruses in prisons: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(6):1078–88.

Sander G, Shirley-Beavan S, Stone K. The global state of harm reduction in prisons. J Correct Health Care. 2019;25(2):105–20.

Cook C, Kanaef N. The global state of harm reduction 2008. Harm Reduct J. 2008;34. https://www.hri.global/contents/551.

Sander G, Lines R. HIV, hepatitis C, TB, harm reduction, and persons deprived of liberty: what standards does international human rights law establish? Health Hum Rights. 2016;18(2):171.

Bick JA. Infection control in jails and prisons. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(8):1047–55.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HAG and MD contributed to the design and implementation of the study, analysis, and interpretation of data, and was involved in drafting the manuscript. DB, AM, MR, and JR contributed to the design and implementation of the study, interpretation of data and was involved in drafting and revising the manuscript. MD, GSh, and HHG contributed to the conception and design of data and drafting the manuscript. SR and MF contributed to the design and implementation of the study and was involved in drafting and revising the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable, because this is a review study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure 1.

Map of Hepatitis B co-infection among prisoners living with HIV by country within different WHO regions (pooled prevalence and 95% CI are shown for each country). Figure 2. Funnel plot for publication bias of the included studies on HBV/HIV co-infection. Figure 3. Egger test for prevalence of HBV among HIV patients. Figure 4. Meta-regression of HBV infection prevalence over time among prisoners living with HIV. Figure 5. Funnel plot for publication bias of the included studies on HCV/HIV co-infection. Figure 6. Egger test for prevalence of HCV among HIV patients. Figure 7. Meta-regression of the association between the prevalence of HCV/HIV coinfections during 1990–2019 in HIV-positive prisoners and year of study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmadi Gharaei, H., Fararouei, M., Mirzazadeh, A. et al. The global and regional prevalence of hepatitis C and B co-infections among prisoners living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty 10, 93 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-021-00876-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-021-00876-7