Abstract

Background

India reports the highest number of tuberculosis (TB) cases worldwide. Poverty has a dual impact as it increases the risk of TB and exposes the poor to economic hardship when they develop TB. Our objective was to estimate the costs incurred by patients with drug-susceptible TB in Bhavnagar (western India) using an adapted World Health Organization costing tool.

Methods

We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional study of adults, notified in the public sector and being treated for drug-susceptible pulmonary TB during January–June 2019, in six urban and three rural blocks of Bhavnagar region, Gujarat state, India. The direct and indirect TB-related costs, as well as patients’ coping strategies, were assessed for the overall care of TB till treatment completion. Catastrophic costs were defined as total costs > 20% of annual household income (excluding any amount received from cash transfer programs or borrowed). Median and interquartile range (IQR) was used to summarize patient costs. The median costs between any two groups were compared using the median test. The association between any two categorical variables was tested by the Pearson chi-squared test. All costs were described in US dollars (USD). During the study period, on average, one USD equalled 70 Indian Rupees.

Results

Of 458 patients included, 70% were male, 62% had no formal education, 71% lived in urban areas, and 96% completed TB treatment. The median (IQR) total costs were USD 8 (5–28), direct medical costs were USD 0 (0–0), direct non-medical costs were USD 3 (2–4) and indirect costs were USD 6 (3–13). Among direct non-medical costs, travel cost (median = USD 3, IQR: 2–4) to attend health facilities were the most prominent, whereas the indirect costs were mainly contributed by the patient’s loss of wages (median = USD 3, IQR: 0–6). Four percent of patients faced catastrophic costs, 11% borrowed money to cover costs and 7% lost their employment; the median working days lost to TB was 30 (IQR: 15–45). A majority (88%) of patients received a median USD 43 (IQR: 41–43) as part of a cash transfer program for TB patients.

Conclusions

Treatment completion was high and the costs incurred by TB patients were low in this setting. However, negative financial consequences occur even in low-cost settings. The role of universal cash transfer programs in such settings requires further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

India is the country with the largest share of the global burden of tuberculosis (TB) cases (27%), with the burden being highest among the poor [1]. Poverty has a dual impact as poor patients are more at risk of TB and may face greater economic hardship when they develop TB [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has suggested no TB patients should face catastrophic costs, defined as costs exceeding 20% of the annual household income, and have included it as a key indicator for TB control [2, 3]. National surveys of costs faced by TB patients are increasingly being done using WHO’s validated costing tool [2]. Studies from Mongolia, Fiji, the Philippines, Vietnam, Uganda, Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria found 27–70% of drug-susceptible TB patients incur catastrophic costs [1, 4,5,6,7]. A study in Peru has established the association of catastrophic health costs with failure to complete treatment [8].

Studies in India reported the percentage of catastrophic costs among drug-susceptible TB patients to be between 7 and 32% [9,10,11,12]. The average costs incurred by drug-susceptible TB patients treated in government health facilities are approximately USD 179, [9, 10] whereas costs incurred by TB patients accessing care in all types of health facilities range from USD 20 to 224 [13,14,15,16,17]. In response to call for additional socioeconomic support for TB patients, the National TB Program (NTP) in India rolled out a direct benefit transfer (DBT) scheme in April 2018 with a credit of USD 7 (Indian Rupees [INR] 500) every month to support the nutritional requirements of TB patients [18]. However, only a few studies have assessed the complete costs incurred through treatment completion by TB patients in India using a validated WHO tool [9, 11, 12].

The primary objective of the study was to estimate the costs incurred by drug-susceptible pulmonary TB patients in a semi-urban and rural setting in western India following the introduction of the DBT scheme. The secondary objective was to estimate the proportion of households facing catastrophic costs and to determine the association between catastrophic costs and failure to complete treatment.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in all six semi-urban and three rural “blocks” (administrative zones) of the Bhavnagar region of Gujarat state in the western part of India. The semi-urban blocks were part of Bhavnagar city (population ~ 0.6 million), and the rural blocks were drawn from the surrounding, largely agricultural, countryside. Agriculture and daily wage labor are the primary occupations of residents in rural and urban areas of the district, respectively. The TB case notification rate in Bhavnagar district from the public and private sector was 1040 and 780 per million population, respectively, in the year 2019. The care for TB is offered free of cost in the public sector in a decentralized model through a network of public health facilities, the district hospital being the tertiary-level facility. Once initiated on treatment, the medicines and other necessary follow-up care is delivered to the patients from a nearby public health facility. Patients with drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis are given a treatment of six months – two months of intensive phase (to rapidly eliminate the bacilli) followed by four months of continuation phase (to eradicate the dormant bacilli).

Design and participants

We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional study of patients enrolled for the treatment of drug-susceptible TB. We included patients ≥ 18 years on treatment for drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis, registered under the public sector in all six urban blocks of Bhavnagar city, and three of 11 randomly-selected rural blocks (Sihor, Palitana, and Mahuva) of Bhavnagar district. We excluded patients who were previously treated or taking treatment under a private health facility or put on treatment for < 14 days [2].

Recruitment

The list (treatment registers) of patients put on treatment is maintained in physical form by TB Health Visitors at the District TB Centre of Bhavnagar. TB health visitors are contracted by NTP for record-keeping of TB patients in geographical areas assigned to them. For each of the nine selected urban and rural blocks, a trained field investigator reviewed the list of patients put on treatment to identify those who appeared to be eligible for the study, and then visited their homes (accompanied by the local TB health visitor) to confirm eligibility and collect data. Enrollment occurred between January 2019 and June 2019. Once patients from all nine blocks were enrolled, the process was repeated in selected urban blocks till June 2019 (end of the study period).

Data collection

Following written informed consent, the field investigator administered a survey to collect basic demographic and clinical information (some of which was extracted from the TB treatment registers), and administered the adapted WHO costing tool [2]. The WHO costing tool included direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs, and indirect costs incurred by the patients for TB care. Apart from the cost questions, the tool also had questions eliciting the income, household ownership of selected assets, coping strategies employed by, and social consequences on the family.

We collected data on costs relative to the following time points based on patient recall: pre-diagnosis (the period from onset of symptoms until diagnosis), at the time of diagnosis, at the end of one-and-a-half month for adverse drug reaction or directly observed treatment (DOT) medicine collection visits, at the end of two months (first follow-up visit) and at the end of six months (treatment completion visit). The survey was administered at the homes of patients and covered all costs up until the time of enrollment in the study, that is, the patients were enrolled at variable time points of treatment. Depending on how far the patient was in the treatment phase, the field investigator later made up to three phone calls to collect data on the additional costs incurred until treatment completion.

The questionnaire was translated into the local language (Gujarati) by a language translator. Compensation of USD 0.7 (INR 50) was given to each participant for their time after completion of the interview. Patients were then followed-up passively to obtain treatment outcomes. The field investigator extracted data on treatment outcomes and DBT from the TB treatment registers and NIKSHAY (an online database for registered TB patients, https://www.nikshay.in/) respectively.

Definitions

Cost data

All costs were summed over various time points. Direct medical costs were categorized as: costs incurred for hospital day charges, consultation charges, and costs for radiography, laboratory, other procedures, drugs, and prescribed nutrition. Direct non-medical costs included: costs for travel, food, and accommodation (including that of an accompanying member) to attend health facility, and the travel costs for DOT visits. Indirect costs included patient’s and accompanying member’s loss of wages, and a measure to assess economic impact calculated as monthly family income before TB minus monthly family income at the time of interview. The total costs incurred were a sum of direct medical, direct non-medical and indirect costs, and were said to be catastrophic if they exceeded 20% of their annual household income (excluding the DBT amount). Negative financial coping strategies (e.g., borrowing money or selling assets) and social consequences (e.g., social exclusion) were also assessed. During the study period, on average, USD 1 equalled INR 70.

Socioeconomic status

To stratify patients based on socioeconomic status, data on ownership of assets including the type of house, number of rooms, television, and others were used to create a standard of living (SLI) index. Depending on the ownership of different assets, a summary score (range: 1–23) adapted from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), was calculated [19, 20]. SLI index score of 1–7 was considered as low SLI and 8–23 was considered as middle/high SLI.

Treatment outcome

Failure to complete treatment was defined according to NTP standards, including loss to follow-up (stopped treatment for at least one consecutive month), sputum smear positivity at the end of treatment, or death while on treatment [21].

Data analysis

We collected data on all eligible patients during the study period of January–June 2019. The data were entered into a computerized form and analyzed in the statistical software EpiInfo 7.2.4.0 (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA). The total costs and its sub-components incurred by patients were described in median with inter-quartile range (IQR). The median costs between any two groups were compared using the median test. The association between catastrophic costs and failure to complete treatment was tested by the Pearson chi-squared test. We conducted sensitivity analyses using 15, 10, and 5% of one’s annual self-reported household income to define catastrophic costs.

Results

Study population

Out of the 2233 total patients, 462 patients were eligible for the study (Fig. 1). Out of those eligible, four patients were removed from the final analysis. The response rate was 100% (all patients agreed to participate in the study).

Characteristics of the study population

The median age of the patients was 35 (IQR: 23–50) years and the median number of family members was 5 (IQR: 4–6). Out of the 458 patients, 70% were male, 62% had no formal education, 72% were married, 71% lived in urban areas and 17% lived in a nuclear family (i.e., lived separately from parents of the primary wage earner) (Table 1). Eighty-eight percent of patients received DBT during the course of treatment (median = USD 43, IQR: 41–43). The median family income of the patients in USD was 129 (IQR: 100–186). Among the study participants, 141 (31%) had low SLI index, 204 (45%) were currently in paid work and 85 (19%) were sole earners in the family. Out of the 458 patients, the sputum smear was positive in 76% of patients, 13% had visited a private practitioner in their first visit and 14% were hospitalized due to TB in their first visit. The median number of days into treatment at the time of enrolment in the study was 69 (IQR: 29–116) days. The proportion of patients who failed to complete treatment was low at 4% (95% CI: 3–6%).

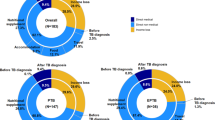

Direct costs

The direct medical costs were minimal for the majority of the patients (median = 0, IQR: 0–0) (Table 2). For the 87% of patients who had their first visit at a government provider these costs were zero, while for those who had their first visit at a private practitioner median direct medical costs were USD 30 (IQR: 10–76). Median direct non-medical costs were USD 3 (IQR: 2–4) and differed significantly between patients who first visited a private vs a government provider (median USD 4 vs 3, P < 0.001). Among direct non-medical costs, travel cost (median = USD 3, IQR: 2–4) to attend health facilities were the most prominent.

Indirect costs

The median indirect costs among the patients were USD 6 (IQR: 3–13) and differed significantly among patients between private vs government providers (USD 20 vs 4, P < 0.001). The indirect costs were mainly contributed by the patient’s loss of wages (median = USD 3, IQR: 0–6).

Total costs

The median total costs incurred by the patients was low (USD 8, IQR: 5–28), but differed significantly among patients who first visited a private vs a government provider (USD 61 vs USD 7, P < 0.001). We found no significant difference in total costs between low and middle/high-income participants (median = USD 8 vs USD 8, P = 0.98, see Supplementary Table 1, Additional file 1).

Catastrophic costs

The percentage of patients who faced catastrophic costs was 4% (95% CI: 3–6%) and remained low in sensitivity analyses using lower thresholds of annual household income to define catastrophic costs (Table 3). Since most patients (96%) completed treatment, we were unable to meaningfully assess the association between catastrophic costs and failure to complete treatment (P = 0.80, data not shown). However, the odds of experiencing catastrophic costs were higher among patients visiting first a private vs a government provider (odds ratio: 4.2, 95% CI: 1.6–11.3, P = 0.002, see Supplementary Table 2, Additional file 2).

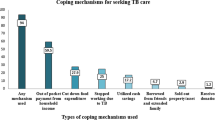

Coping strategies and social consequences

Among the 458 patients, 18% of patients had employed at least one negative financial coping strategy (Table 4). Eleven percent of households had to borrow a median of USD 71 (IQR: 29–143) to cover costs incurred after starting TB treatment. Also, one (0.25%) patient’s household stopped the tuition of their child to cover the cost of illness and two (0.5%) patient’s family members left their job to take care of them during their illness. Seven percent of patients lost their employment; the median of the working days lost to TB was 30 (IQR: 15–45). Also, the spouse of one (0.25%) patient gave divorce and family of one (0.25%) patient stopped talking with the patient due to TB.

Discussion

Patients in this study had relatively low TB-related costs. This was particularly true for the 87% of patients who first visited the public sector as opposed to a private health care provider since direct medical charges for the former were zero. Among patients treated by private providers, the median total costs were USD 61 (IQR: 35–156). As a result of the lower overall costs in this population, the percentage who faced catastrophic costs was also low. Despite these low overall costs, 18% of families reported having to employ at least one negative financial coping strategy to manage their anticipated and actual costs.

The median costs reported in the present study were lower than those reported in most other studies from India [9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 17, 22, 23]. The discrepancy might be because the current study estimated the costs among drug-susceptible pulmonary TB patients, whereas the published literature is inclusive of cost estimates on drug-resistant and extra-pulmonary TB patients. The course of treatment for the latter group is longer and more complicated as compared with drug-susceptible TB patients. In addition to the difference in groups studied, most of the previous studies were conducted in a metropolitan city in contrast to the present study setting of a semi-urban and rural area. Finally, the current study was conducted among patients who were taking treatment at a government health facility, nullifying the post-diagnostic direct medical costs which might have been incurred at a private health facility.

When compared with other high-burden countries [1, 4,5,6,7], the present study reported a low percentage of households facing catastrophic costs. There is a possibility of underestimation of patient costs. Evidence suggests that the self-reported annual household incomes are lower than estimates based on assets, consumption, or expenditure [24]. However, most studies in other countries also used self-reported income and the percentage of households facing catastrophic costs found in the present study were comparable to a recent study conducted in New Delhi [9]. In contrast to the present study, a study in Peru found a significant association between catastrophic costs and adverse treatment outcomes among tuberculosis patients [8]. However, their research was conducted among drug-resistant TB patients who are more likely to incur higher costs and more likely to experience adverse treatment outcomes as compared with drug-susceptible TB patients [25, 26].

Around one-fifth of the patients in the current study employed a negative financial coping strategy to cover the costs of TB care. Negative financial coping strategies, also called dissavings, are directly associated with costs incurred by TB patients and may be used as a proxy indicator of the financial protection mechanisms being employed by governments [27]. Further program evaluation and implementation research are required to assess how cash transfer schemes like DBT can be better targeted to affect these outcomes [28, 29].

Several aspects of the study context likely affected these results. Study setting being a small town, patients faced less direct non-medical costs (costs for travel, food, accommodation, etc.) due to proximity to public health facilities. The setting where the present study was conducted has a wide network of government-run diagnostic and treatment facilities for tuberculosis. The public-private partnership model for TB control seems to be effective in Bhavnagar as the majority of patients had their first or second visit at a public health facility. The private practitioners seem to be aware of referring patients to public health facilities for reducing their economic hardships. Even though patients have to collect their medicines weekly, their medicine boxes are placed somewhere near to their homes (either a family member, neighbor, private practitioner, or health worker act as the DOT provider). This decentralized model of DOT helps to minimize direct non-medical costs incurred for such visits.

This was a single-center study in a semi-urban and rural setting with a well-functioning community-based DOT program that is achieving high levels of treatment success. Therefore the findings should only be generalized to similar settings in India. Even though this is one of the initial studies from India using the validated WHO tool [2] and adheres to the guidelines of reporting cross-sectional studies [30], it has some limitations. Some like recall bias and assessing costs after treatment completion are inherent to costing studies and were unavoidable, but, could have contributed to costs being underestimated.

Conclusions

We conclude from the study that TB patients in our region incur minimal costs, perhaps due to the highly decentralized provision of diagnostic and treatment services through community-based DOT. These findings support the further expansion of community-based DOT models to reduce catastrophic costs in India and other countries. However, almost one in five participants undertook negative financial coping strategies to facilitate TB care, suggesting that negative financial consequences occur even in low-cost settings. Further research is needed to assess whether universal cash transfer programs achieve social protection targets in settings with well-functioning community-based DOT programs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Mendeley repository, https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/t3gb7f6xrx/1

Abbreviations

- CI :

-

Confidence interval

- DBT:

-

Direct benefit transfer

- DOT:

-

Directly observed treatment

- ICMR:

-

Indian Council of Medical Research

- INR:

-

Indian Rupee

- IQR:

-

Inter-quartile range

- NFHS:

-

National Family Health Survey

- NTP:

-

National TB Program

- SLI:

-

Standard of Living index

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- USD:

-

United States Dollars

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2019. Geneva: WHO Press; 2019.

World Health Organization. Tuberculosis patient cost surveys: a handbook. Geneva: WHO Press; 2017.

World Health Organization. The end TB strategy. Geneva: WHO Press; 2015.

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2018. Geneva: WHO Press; 2018.

Viney K, Islam T, Hoa NB, Morishita F, Lönnroth K. The financial burden of tuberculosis for patients in the Western-Pacific region. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;4(2):94.

Nhung NV, Hoa NB, Anh NT, Anh LTN, Siroka A, Lönnroth K, et al. Measuring catastrophic costs due to tuberculosis in Viet Nam. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22:983–90.

Ministry of Health (Uganda). Direct and indirect costs due to tuberculosis and proportion of tuberculosis-affected households experiencing catastrophic costs due to TB in Uganda. Uganda: Ministry of Health; 2019.

Wingfield T, Boccia D, Tovar M, Gavino A, Zevallos K, Montoya R, et al. Defining catastrophic costs and comparing their importance for adverse tuberculosis outcome with multi-drug resistance: a prospective cohort study, Peru. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001675.

Sarin R, Vohra V, Singla N, Thomas B, Krishnan R, Muniyandi M. Identifying costs contributing to catastrophic expenditure among TB patients registered under RNTCP in Delhi metro city in India. Indian J Tuberc. 2019;66:150–7.

Prasanna T, Jeyashree K, Chinnakali P, Bahurupi Y, Vasudevan K, Das M. Catastrophic costs of tuberculosis care: a mixed methods study from Puducherry, India. Glob Health Action. 2018;11:1477493.

Chandra A, Kumar R, Kant S, Parthasarathy R, Krishnan A. Direct and indirect patient costs of tuberculosis care in India. Tropical Med Int Health. 2020;25(7):803–12.

Muniyandi M, Thomas BE, Karikalan N, Kannan T, Rajendran K, Saravanan B, et al. Association of tuberculosis with household catastrophic expenditure in South India. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1920973.

Muniyandi M, Thomas BE, Karikalan N, Kannan T, Rajendran K, Dolla CK, et al. Catastrophic costs due to tuberculosis in South India : comparison between active and passive case finding. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2020;114(3):185–92.

Muniyandi M, Rajeswari R, Rani B. Costs to patients with tuberculosis treated under DOTS programme. Indian J Tuberc. 2005;52:188–96.

Muniyandi M, Rao V, Bhat J, Yadav R, Sharma R. Household catastrophic health expenditure due to tuberculosis: analysis from particularly vulnerable tribal group, Central India. Med Mycol Open Access. 2016;2:1–9.

Ray TK, Sharma N, Singh MM, Ingle GK. Economic burden of tuberculosis in patients attending DOT centres in Delhi. J Commun Dis. 2005;37:93–8.

John KR, Daley P, Kincler N, Oxlade O, Menzies D. Costs incurred by patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in rural India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1281–7.

Central TB Division. Government of India. Nutritional Support to TB patients (Nikshay Poshan Yojana). New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2018.

International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2) 1998–99. Mumbai, India; 2000.

Muniyandi M, Ramachandran R, Gopi PG, Chandrasekaran V, Subramani R, Sadacharam K, et al. The prevalence of tuberculosis in different economic strata: a community survey from South India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11:1042–5.

Central TB Division. Government of India. Revised National TB Control Programme: Technical and Operational Guidelines for Tuberculosis Control in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2016.

Mullerpattan JB, Udwadia ZZ, Banka RA, Ganatra SR, Udwadia ZF. Catastrophic costs of treating drug resistant TB patients in a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian J Tuberc. 2019;66:87–91.

Rathi P, Shringapure K, Unnikrishnan B, Chadha VK, Acharya V, Nair A, et al. Pretreatment out-of-pocket expenses for presumptive multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients, India, 2016–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2016–7.

Sweeney S, Mukora R, Candfield S, Guinness L, Grant AD, Vassall A. Measuring income for catastrophic cost estimates: limitations and policy implications of current approaches. Soc Sci Med. 2018;215:7–15.

Rouzier VA, Oxlade O, Verduga R, Gresely L, Menzies D. Patient and family costs associated with tuberculosis, including multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, in Ecuador. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:1316–22.

Deshmukh RD, Dhande DJ, Sachdeva KS, Sreenivas A, Kumar AMV, Satyanarayana S, et al. Patient and provider reported reasons for lost to follow up in MDRTB treatment: a qualitative study from a drug resistant TB Centre in India. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–11.

Madan J, Lönnroth K, Laokri S, Squire SB. What can dissaving tell us about catastrophic costs? Linear and logistic regression analysis of the relationship between patient costs and financial coping strategies adopted by tuberculosis patients in Bangladesh, Tanzania and Bangalore, India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:1–8.

Wingfield T, Tovar MA, Huff D, Boccia D, Montoya R, Ramos E, et al. The economic effects of supporting tuberculosis-affected households in Peru. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:1396–410.

Kundu D, Katre V, Singh K, Deshpande M, Nayak P, Khaparde K, et al. Innovative social protection mechanism for alleviating catastrophic expenses on multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Chhattisgarh , India. WHO South-East Asia J Public Heal. 2015;4:69–77.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1500–24.

Acknowledgements

The protocol and the manuscript for this research were developed and drafted respectively in Methods in Epidemiologic, Clinical, and Operations Research (MECOR) program of the American Thoracic Society (ATS, New York, USA). The ATS-MECOR is a program primarily aimed at low- and middle-income countries to build their local and national capacity in lung health research. We thank the patients for participating and the staff of the District TB Centre of Bhavnagar for their support during data collection in the study. We also thank Dr. Mayur Trivedi (IIPH Gandhinagar) for helping us to adapt the Standard of Living Index for the study. We also thank Ms. Rushita Radadiya, field investigator, for her meticulous efforts in data collection and entry.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Thoracic Society (ATS Foundation, New York, USA) under their MECOR research awards (grant number ATS-2017-29; the first author received a grant of USD 5000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to conception, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search, data analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review. The first author (MPR) acquired the funding and drafted the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors reviewed and edited the manuscript for corrections. All the authors approve the final version of the article. The first author will act as the guarantor of the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Government Medical College Bhavnagar (No. IRB-HEC/772/2018, dated 20-03-2018) and the Health Ministry Screening Committee of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Written informed consent was taken from study participants before the interview.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Median costs in USD by standard of living index. Table showing median (with inter-quartile range) costs incurred by 458 patients with drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis on treatment during January–June 2019.

Additional file 2.

Association between type of provider at first visit and catastrophic costs. Table showing statistical association between type of provider at first visit and catastrophic costs incurred by 458 patients with drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis on treatment during January–June 2019.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rupani, M.P., Cattamanchi, A., Shete, P.B. et al. Costs incurred by patients with drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis in semi-urban and rural settings of Western India. Infect Dis Poverty 9, 144 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00760-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00760-w