Abstract

Methods for determining the various thermodynamic and kinetic parameters required for the modeling of γ′ precipitation in powder-metallurgy (PM), nickel-base superalloys are summarized. These parameters comprise the composition of the γ′ phase, the γ′ solvus temperature/equilibrium solvus approach curve, the free energy (∆G*) associated with the decomposition of the γ matrix to form γ′, the γ/γ′ interfacial energy σ, and an effective diffusivity for use in nucleation, growth, and coarsening calculations. Techniques to obtain the material data include phase extraction (for the average composition of γ′) and heat-treatment/quantitative metallography (for a two-parameter fit of the solvus approach curve). With regard to ∆G*, two methods, one based on the instantaneous composition of the γ and γ′ phases and the other on the enthalpy of transformation and the solvus temperature, are summarized. It is shown that the interfacial energy σ can be determined from the nucleation-onset temperature as indicated by on-cooling specific-heat measurements. Last, the use of a limited set of static-coarsening measurements to estimate the effective diffusivity is described. The application of the various protocols is illustrated for typical first-, second-, and third-generation PM superalloys, i.e., IN-100, René 88, and LSHR/ME3, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Nickel-base superalloys comprise an important class of high-temperature structural materials used widely in jet-engine and land-based, power-generation applications [1]. Depending on alloy content and intended service, superalloys are typically synthesized via ingot metallurgy (IM; aka cast + wrought), powder-metallurgy (PM), or investment-casting (IC) methods [1, 2]. Lean alloys, which are not prone to macro-segregation or thermal cracking in ingot form, are usually made via the first technique. PM methods are employed to manufacture semi-finished billet products and are common for more-highly alloyed materials prone to segregation or thermal cracking when cast in large diameters. Investment casting is frequently applied for the net-shape manufacture of components of the most-highly alloyed compositions. Irrespective of processing method, however, all superalloys rely on various combinations of precipitation and solid-solution strengthening of the face-centered cubic (fcc) gamma (γ) matrix to maintain high-temperature strength.

The principal strengthening precipitates in nickel-base superalloys consist of the ordered fcc gamma-prime (γ′) and ordered body-centered tetragonal (bct) gamma-double-prime (γ″) phases [1–3]. The former are commonly found in all three types of alloys (IM, PM, IC) and have a composition of Ni3X, in which X = Al, Ti, Ta, and Nb. The latter precipitates are most common in IM materials such superalloy 718 and have a composition of Ni3Nb. Alloy 718 often has additional, coarser Ni3Nb delta (δ) precipitates (with an orthorhombic crystal structure) that form at higher temperatures and are used primarily to control the size of the γ grains.

Processing temperatures for nickel-base superalloys are usually chosen relative to the precipitate solvus (or solvi, as is the case for 718), i.e., the temperature(s) above which all precipitates are dissolved. For example, following powder synthesis and consolidation via blind-die compaction or hot isostatic pressing, γ′-strengthened PM superalloys are typically extruded at a subsolvus temperature to develop a fine, recrystallized billet microstructure composed largely of γ grains and primary γ′ precipitates. The average diameter in each phase is of the order of 1 to 5 μm. Under low-strain-rate processing conditions in the two-phase field, alloys with this microstructure are superplastic. Sections cut from the billet product are thus readily shaped via isothermal-forging techniques.

Depending on the service application, subsequent heat-treatment conditions are also selected relative to the solvus. For applications requiring high strength and resistance to fatigue-crack initiation, heat treatment for γ′-strengthened alloys consists of solution treatment below the γ′ solvus, free- or forced-air cooling to room temperature, and final aging. The γ′ precipitates formed from such a heat treatment are denoted as primary (retained from prior subtransus processing during soaking at the solution temperature), secondary (formed at higher temperatures during cooling following solution treatment), and tertiary (formed at lower temperatures during cooldown and during final aging). For applications requiring good creep strength and crack-growth resistance, a solution heat treatment consisting of supersolvus exposure to grow the γ grain size is typical. In this case, secondary and tertiary γ′ precipitates are formed during cooling.

Because of the importance of precipitation to the mechanical properties, it is not surprising that considerable work has been performed to model it in terms of pertinent nucleation, growth, and coarsening phenomena [4–24]. A number of efforts have focused on γ-γ′ superalloys in particular, primarily for the isothermal heat treatment of alloys with 2, 3, or 4 components [25–29]. Several investigations have also examined the more complex case of continuous cooling of multi-component commercial alloys [30–36]. Furthermore, classical deterministic analyses of precipitation have been complemented by more-detailed statistical treatments such as those based on the phase-field method, e.g., references [37–41]. Although computationally more intensive, these approaches are often used to quantify those conditions under which precipitates evolve from a spheroidal to a cuboidal shape as they grow large. Thus, they can provide better quantitative predictions of the size of large precipitates than classical analyses that assume spheroidal growth only.

The objective of the present work was to develop engineering methods for determining the input material data for classical models of intragranular γ′ precipitation,Footnote 1 especially those parameter descriptions that can be utilized readily in fast-acting numerical simulations. The efficacy of the approaches was demonstrated for several commercial PM superalloys. To provide context for this work, the various models used to describe precipitation are summarized first.

Fundamentals of precipitation modeling

Typical modeling procedures for precipitation are based on classical relations for the rate of homogeneous nucleation, diffusional growth, and static coarsening.

Nucleation rate

The rate of nucleation of precipitates, J, is given by the following equation [4, 12, 26]:

in which C denotes the solute content in the matrix expressed as an atomic fraction, D is the solute diffusivity in the matrix phase, a o is the average lattice parameter of the matrix and precipitate phases (taken to be ~0.356 nm for most γ-γ′ superalloys), σ is the matrix-precipitate surface energy, k B is Boltzmann’s constant (1.3806 JK−1), T is the temperature in Kelvin, and t is the time. The critical radius of the precipitate, r*, is a function of σ, the chemical free energy of transformation, ∆G* (taken to be a positive quantity for a decrease in energy), and the elastic strain energy, ∆G p, associated with the difference in lattice parameters of the matrix and precipitate phases, i.e.,

The nucleation rate J in Eq. (1) is related to the steady-state nucleation rate J o through the term exp(−τ/t), which describes the initial nucleation transient during which a metastable distribution of embryos with sub-critical radii are formed. The so-called incubation time constant τ in this exponential term is given by the relation [26, 42]:

in which R is the gas constant, and V M is the molar volume of the precipitate.

Strictly speaking, Eqs. (1)–(3) apply to nucleation in two-component alloys. Methods and assumptions utilized to determine effective values for coefficients such as C, D, and ∆G* of multi-component alloys for use in the nucleation (as well as growth and coarsening) relations are discussed below.

Diffusional growth

In most theoretical treatments for γ′ precipitates, the particles are assumed to be spherical of radius r with their growth controlled by diffusion. The “exact” solution of the diffusion equation for the rate of growth in the presence of a finite matrix supersaturation is as follows [13, 14]:

in which λ 2 is related to the supersaturation Ω by the following relation:

The supersaturation Ω has its usual definition, i.e.,

Here, C m, C i, and C p represent the compositions of the matrix far from the matrix-particle interface, the matrix at the matrix-particle interface, and the particle at the matrix-particle interface, respectively. The correction to the equilibrium (r = ∞) interface composition, C i, due to the Gibbs-Thompson effect can be quantified using the following equation [43]:

The effect of soft impingement on the “far-field” matrix composition C m is taken into account using the usual approximation derived from a mass balance [44]:

in which C o and f denote the overall alloy composition and the volume fraction of the precipitate.

As for the nucleation-rate relation (Eq. (1)), the diffusional-growth solution (Eq. (4)) is strictly applicable to a two-component system whose inter-diffusion coefficient is independent of composition. For multi-component alloys, D thus represents again an effective diffusivity (D eff). Furthermore, it is often assumed in fast-acting simulations that the composition of the γ′ precipitate is constant and equal to the average value determined by phase extraction.

Coarsening

During continuous cooling at rates typical of production-scale components, the tendency for coarsening of γ′ precipitates (especially the larger secondary precipitates) is small due to retained supersaturation. On the other hand, coarsening during aging (and during service at high temperatures) can be quite substantial. In the present work, measurements of the isothermal, static-coarsening rate have been used to estimate the effective diffusivity needed in the expressions for both nucleation and growth. Specifically, the rate of increase of the average precipitate size was interpreted in terms of the classical Lifshitz-Slyozov-Wagner (LSW) theory modified to treat the coarsening of finite volume fractions of particles (15, 16, 21), viz.:

and

In Eq. (9), \( \overline{r} \) and \( {\overline{r}}_{\mathrm{o}} \) represent the average instantaneous and initial particle radii. In the expression for the modified LSW rate constant, K MLSW, terms not previously defined include w(f), the factor to correct for the finite volume fraction of particles [17–20], and C γ and C γ′, the equilibrium concentrations of the rate-limiting solute in the matrix and precipitate, respectively. The bracketed term in the denominator of Eq. (10) is the thermodynamic factor in which v denotes the activity coefficient for the rate-limiting solute in the γ matrix of specified composition.

Again, the formulation and application of Eqs. (9) and (10) for multi-component alloys implicitly assumes that coarsening is controlled by the diffusion of a single, rate-limiting solute. However, Kuehmann and Voorhees [24] demonstrated that rapidly diffusing solutes can also affect the coarsening rate and the related diffusional processes for ternary alloys. For multi-component alloys, their work suggests that an effective rate constant (K eff) equal to the inverse of the sum of the inverse rate constants for the individual solutes can be defined as follows:

Model input data: approaches and examples

The key material parameters for modeling of precipitation belong to one of three sets: (i) thermodynamic data, (ii) driving/retarding forces for nucleation, and (iii) kinetic factors/diffusivity. Each of these is discussed in more detail below with pertinent results for the first-, second-, and third-generation superalloys IN-100, René 88, and LSHR/ME3, respectively.

Thermodynamic data

The key thermodynamic data consist of (1) the solvus approach curve (equilibrium fraction of γ′ as a function of temperature, f(T), for γ-γ′ superalloys), (2) the composition of the γ′ phase, and (3) the solute content in the matrix (C in Eq. (1)).

Two methods exist for determining the solvus approach curve. The first is the formal Calphad (thermodynamic) method based on the calculation of the fractions of γ and γ′ as a function of temperature using the Gibbs free energies of these phases [45]. For multi-component alloys such as commercial nickel-base superalloys, these calculations require an appropriate thermodynamic database typically obtained through the optimization of a number of model parameters from various measured binary, ternary, etc. phase diagrams. An alternate, semi-empirical method was developed by Dyson [46] and refined by Payton [47]. Specifically, it comprises fitting f(T) measurements to an analytical expression, whose application is especially attractive for fast-acting simulations of precipitation kinetics, viz.,

Here, T γ′ denotes the γ′ solvus temperature, C* is the atomic fraction of γ′ formers in the alloy, and Q is a fitting parameter. Because the γ′ phase has a composition of Ni3X, 4C* is approximately equal to the maximum volume fraction of γ′ in the alloy, i.e., the amount at 0 K. The value of the fitting parameter Q typically lies in the range of 60 to 75 kJ/mol.

The applicability of Eq. (12) is illustrated using IN-100, René 88, and LSHR as model alloys. From heat treatments at various temperatures followed by metallography, the solvus temperature for the three materials has been determined to be 1458, 1378, 1430 K, respectively. Typical compositions of the alloys are summarized in Table 1 (in weight percent) and Table 2 (in atomic percent). For the superalloys of interest here, the principal γ′-forming elements are Al, Ti, Nb, and Ta. From Table 2, the values of 4C* are thus 0.60, 0.38, and 0.53. These estimates are in reasonable agreement with published reports of the fraction of γ′ in fully heat-treated materials except for René 88, for which the measured volume fraction is 0.42, rather than 0.38 [30]. Differences between estimated and published magnitudes of the volume fraction of precipitate can be largely ascribed to the fact that the various γ′-forming elements do not partition totally to this phase, and the other alloying elements do not fully partition to the γ matrix. The specific alloying-element partitioning is illustrated by measurements of the average composition of γ′ determined by phase extraction (Table 3) [48]. This method weights the composition in favor of those precipitates with the larger volume fractions, i.e., the primary and secondary γ′, of course.

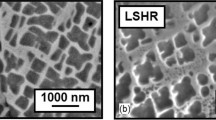

Using the above values of T γ′ and 4C*, measurements of the equilibrium volume fractions of γ′ at various temperatures for each alloy have been fitted to Eq. (12) (Fig. 1). The measurements were performed via quantitative analysis of SEM micrographs taken on samples that had been heat treated for long times (4–24 h, depending on temperature) or isothermally forged to achieve equilibrium conditions. The best fits are obtained for Q = 75, 65, or 60 kJ/mol for IN-100, René 88, and LSHR, respectively. In Fig. 1b, the René 88 measurements and the fit using Eq. (12) also show good agreement with the solvus approach curve determined by a Calphad-type approach [49]. In addition to the precise shape of the free-energy curves as a function of temperature, the variation in the value of Q for the three alloys may be due to uncertainties in the measured volume fractions of γ′ used for fitting (approximately ±0.015) and the precise values of the maximum volume fraction of γ′ (assumed to be 4C*).

The solute content in the matrix (C in the nucleation Eq. (1)) depends on the volume fraction of precipitate and its composition. For supersolvus solution treatments, the majority of the secondary-γ′ nuclei form during a short time interval during which the matrix composition undergoes little change. Thus, C is relatively constant and equal to ~0.45–0.50 (Table 2). Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis in reference [50] has shown that C equal to 0.25, 0.5, or even the physically unrealistic value of 1.0 all yield similar precipitation predictions.

Driving force for nucleation

The principal driving force for nucleation is the reduction in chemical free energy, ∆G*, associated with the formation of γ′ from a supersaturated γ matrix. In addition to the formal Calphad approach, two somewhat simpler engineering methods can be used to determine ∆G* [50]. One is based on measurements of the specific heat and the γ′ solvus temperature. The other involves a thermodynamic calculation based on a pseudo-binary of nickel and chromium.

The first technique for determining ∆G* is strictly applicable to the matrix composition pertaining to supersolvus solution treatment, i.e., the overall alloy composition. Assuming that the enthalpy (∆H avg) and entropy (∆S avg) of formation (per mol) are constant, ∆G* varies linearly with temperature, i.e.,

The enthalpy of formation of the precipitate phase, ∆H avg, is determined from the integral of the measured specific heat (C p) over the on-cooling-transformation-temperature range (typically ~30 K below the solvus → ~1150 K for PM nickel-base superalloys). This integral is decremented by the heat content associated with temperature changes in the absence of transformation as quantified by extrapolations from low and high-temperature C p behaviors, respectively. A schematic illustration of the construction, in which the enthalpy of transformation is shown as the cross-hatched region, is shown in Fig. 2. Knowledge of the fraction transformed (f trans) yields the desired quantity:

At the γ′ solvus, ∆G* is equal to zero. Thus, the value of ∆S avg is equal to ∆H avg/T γ′.

Specific-heat data measured during cooling from above the solvus at a rate of 20 K/min reveal a similar dependence on temperature for IN-100, René 88, and LSHR (Fig. 3) [51–54]. Results for ME3, an alloy whose overall composition and γ′ composition are similar to those of LSHR (Tables 1, 2, and 3), are also included in Fig. 3c. All of the measurements indicate a finite undercooling below the solvus at which the transformation begins, a peak just below this onset temperature, and a rapid decrease in the magnitude of C p thereafter. The rate of decrease after the peak can be ascribed to the decreasing rate of formation of γ′ inasmuch as the instantaneous fraction of precipitate follows the solvus approach curve, at least approximately, once nucleation starts to occur [50]. The estimates of ∆H avg and ∆S avg (Table 4) show very similar results for IN-100 and LSHR, but a measurable difference for René 88.

On-cooling specific-heat-versus-temperature measurements for a IN-100, b René 88, and c LSHR. For IN-100 and René 88, the two sets of measurements (black, red) were taken approximately 9 months apart on different samples from the same billet. For LSHR, the red and black data pertain to samples from two different billets measured approx. 10 years apart. The LSHR results are compared to the behavior for the alloy ME3 (in blue) in c

The second approach used to quantify ∆G* is based on classical expressions from solution thermodynamics. For the case in which the precipitate is enriched in solute (which is applicable for Al, Ti, Nb, Ta), ∆G* is given by [4]:

A similar relation applies when the precipitate is depleted in solute (e.g., Cr, Co), i.e.,

in which all of the terms are the same as defined above.

Values of ∆G* for an undercooling of 30 K below the solvus temperature have been calculated for a supersaturated solid solution produced by supersolvus heat treatment of IN-100, René 88, and LSHR; i.e., C m = solute content specified by the overall alloy composition. The calculations utilized Eq. (15) with the alloy/phase composition data in Tables 2 and 3 and estimates of the thermodynamic factor for each alloying element from the commercial code Pandat™ (CompuTherm LLC, Madison, WI) (Table 5). The equilibrium solute composition in the matrix (C γ) was determined from the precipitate composition (Table 3) and the equilibrium volume fraction of γ′ per the solvus approach curves (Fig. 1). The results of the calculations (Table 5) reveal that the largest values of ∆G* correspond to those for chromium for all of the alloys. As suggested by the composition data in Tables 2 and 3, this behavior may be ascribed to a very high level of solute partitioning between the γ and γ′ phases for this element.

The importance of chromium in controlling the driving force for nucleation is confirmed by a comparison of the predicted variation of ∆G* with temperature from the methods based on either Eq. (13) or Eq. (15b) (for Cr solute) for a supersaturated solid solution produced by supertransus solution treatment. The comparison for IN-100 and LSHR shows excellent agreement (Fig. 4a). Although not formally appropriate, predictions from Eq. (15a), also plotted in Fig. 4a, show very good agreement with those from Eqs. (13) and (15b) as well. Furthermore, a comparison of the ∆G* dependence on temperature for supersolvus-solution-treated alloys LSHR and ME3, derived using Eq. (15b), shows essentially identical results. This behavior is as expected based on the very similar alloy and γ′ compositions, in particular with respect to the Cr content (Tables 2 and 3).

Temperature dependence of ∆G* for nucleation of γ′ for supersolvus-solution-treated PM superalloys: a results for IN-100 and LSHR predicted using Eq. (13), (15b), or (15a), the latter two relations based on Cr partitioning and b comparison for LSHR and ME3 using Eq. (15b) based on Cr partitioning. The results in b indicate negligible difference for the two alloys

For the general case of an arbitrary solution temperature and non-zero values of the precipitate volume fraction, Eq. (15) is readily applied to determine ∆G* and is thus typically used in fast-acting simulations.

Retarding force for nucleation

The principal retarding force for nucleation consists of the creation of γ-γ′ interfaces with their associated interfacial energy σ. The determination of σ is usually based on the temperature at which “noticeable” nucleation occurs. This onset temperature per se can be deduced using a variety of techniques including in situ (synchrotron) x-ray diffraction (e.g., reference [50]), differential thermal analysis (DTA), and on-cooling specific-heat measurements. The application of the latter technique is shown in Fig. 3, which reveals the temperature/undercooling at which the specific heat begins to rise noticeably. These temperatures are found to be 1431, 1345, and 1403.5 K (corresponding to an undercooling of 27, 33, or 26.5 K), respectively, for IN-100, René 88, and LSHR/ME3. The onset temperature and critical undercooling for LSHR from the specific heat are essentially identical to the values determined previously for LSHR via the synchrotron method [50]. Furthermore, the previous in-situ results indicated that the onset temperature is identical for cooling rates of 11 and 139 K/min.

Following an approach similar to that suggested by Doherty [4], the surface energy is chosen to yield a value of J o (per Eq. (1) with a diffusivity based on static-coarsening measurements, as discussed below) that is discernable by post heat-treatment metallography. For cooling rates of the order of 0.2–2 K/s, a critical J o of the order of 1/μm3s (1018/m3s) at the observed nucleation-onset temperature is reasonable. Examples of the determination of σ for IN-100, René 88, and LSHR by this means are summarized in Fig. 5. The surface energies so deduced are between 23 and 25 mJ/m2. Because of the exponential dependence of nucleation rate on σ 3, the use of a different value for the “critical” value of J would have led to only a small difference in the appropriate choice of σ. For example, if the critical J were chosen to be 0.1/μm3s, the surface energy for the three alloys would have been between 24 and 26 mJ/m2 per the plots in Fig. 5.

The values of σ in the present work are almost identical to that deduced by Sudbrack et al. [28] for a ternary Ni-Al-Cr alloy with levels of aluminum and chromium similar to those in IN-100 and LSHR. By contrast, the present value is considerably lower than the value quoted by Olson et al. [35] for LSHR (i.e., 31.5 mJ/m2). Perhaps, this difference can be rationalized in the context of values of ∆G* which may have been too high in the earlier prior work. For example, an examination of Eqs. (1) and (2) indicates that the nucleation rate depends on an exponential term whose argument includes a factor of σ 3/∆G*2. Thus, to obtain an identical/observable nucleation rate at a given temperature, a surface energy that was high by a factor of approximately 35 pct would have required that ∆G* to be overestimated by 57 pct.

The misfit energy ∆G p can also act as a retarding force through its effect in raising the overall system energy in much the same way that the interface energy does as precipitates are formed [55]. However, in most cases, ∆G p is small relative to that of ∆G* and can be neglected to a first order or included implicitly with ∆G*. For example, Booth-Morrison et al. [56] determined that the misfit was ~0.2 pct for the ternary alloy Ni-5.2Al-14.2Cr (in atomic percent), i.e., a material whose levels of chromium and aluminum are similar to those in commercial PM superalloys. For this level of misfit, ∆G p would be of the order of 1 J/mol. Such a value is two orders of magnitude smaller than the values of ∆G* for temperatures at which secondary and tertiary γ′ nucleation occurs.

Effective diffusivity, D eff

The diffusivities of various solutes in nickel-base superalloys play a very important role in the precipitation process through their effect on particle growth per se as well as the rate of depletion of the matrix supersaturation controlling nucleation behavior. Because alloying elements such as Al and Ti partition in a sense opposite to that of Cr in the γ and γ′ phases and the off-diagonal terms in the diffusivity matrix are non-zero, the development of a concentration gradient for one alloying element may noticeably retard the overall diffusive flux of another. For example, Al and Cr in a nickel solid solution have a positive interaction such that Al can diffuse down a chromium concentration gradient [57–59]. Thus, as a γ′ precipitate grows, the rate of diffusion of a given element to or away from the particle may be mitigated somewhat by its tendency to diffuse down the concentration gradient of a different alloying element.

Because of the complexity of the diffusion problem, it is therefore often simpler to determine an effective diffusivity for the alloying element whose behavior appears to be rate limiting and to which simple (pseudo-binary) diffusion analyses can be applied. For PM nickel-base superalloys such as those of interest here, the work of Campbell et al. [60] and Semiatin et al. [50] suggests that Cr diffusion is rate limiting in γ-γ′ superalloys.

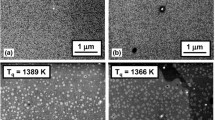

In the present work, the specific method used to fit an effective diffusivity has been based on an analysis of the rate of coarsening of intragranular, secondary γ′ during isothermal heat treatments. In particular, experimental observations (e.g., Fig. 6 for IN-100 and Fig. 7 for René 88) were interpreted using Eq. (10), assuming that the process has been controlled solely by Cr diffusion, or Eqs. (10) and (11) to account for the influence of all of the solutes. In both analyses, the effective diffusivity of Cr as a function of temperature was taken equal to the product of the impurity diffusivity, D B, of Cr in binary Ni-Cr alloys [61] (principally to obtain the activation energy/temperature dependence) and a fitting factor, A, to account for the finite concentration of Cr in the γ matrix and its interaction with other solutes, i.e.,

The diffusivities of the various other solutes in each alloy were taken to be in the ratios (relative to that of Cr) suggested by the work of Campbell et al. [60]. In addition, w(f) was taken from the research of Voorhees and Glicksman [20], and σ was assumed to be 23 mJ/m2 per the results in Fig. 5. The molar volume V M was calculated to be 7.20 × 10−6, 7.11 × 10−6, and 7.22 × 10−6 m3/mol for IN-100, René 88, and LSHR, respectively. The thermodynamic factors needed to apply Eq. (10) were derived from Pandat™ calculations (Table 6).

Predicted coarsening rate constants for IN-100, René 88, and LSHR at various temperatures and two different values of A (= D eff/D B), 0.33 and 0.8, are summarized in Table 7. For a given alloy, temperature, and value of A, the calculations reveal that the predicted coarsening rate based on Cr diffusion alone (Eq. (10)) is approximately 1.5 to 3 times that determined when accounting for the interaction among the solutes using Eqs. (10) and (11). Table 7 also summarizes measured rate constants based on SEM observations on 2D sections (e.g., those in Figs. 6 and 7). Two different methods were used to reduce such measurements. In one case (i.e., annotated as “SC”, or “stereological correction”), it was assumed that the true 3D diameters were 15 pct larger than those measured on the 2D sections. In the other case, no such SC was applied. This latter approach has been justified based on recent geometric analysis by Payton et al. [62] for distributions of spherical particles that have finite breadth, as is pertinent for precipitates undergoing coarsening. Specifically, it was deduced that the SC used in the first case overestimates the actual average 3D size and that no correction factor is actually needed for distribution shapes such as those developed during static coarsening.

Taken as a whole, the comparison of predicted and measured values of the coarsening rate constant (Table 7) shows two important trends. First, A = 0.8 is more appropriate for IN-100 and René 88, but a lower value, A = 0.33, gives a better fit for LSHR. Second, the predicted rate constants based on the interaction of all of the solutes are closer to the measurements than those based on diffusion of Cr alone. In fact, the agreement is remarkably good for the various alloys and different temperatures when the calculation incorporates the effect of all of the solutes and uses A = 0.8 for the first- and second-generation alloys and A = 0.33 for the third-generation alloy. The generality of this conclusion has been confirmed in a companion report [63] containing additional coarsening data and analysis for three third-generation PM alloys (LSHR, ME3, Alloy 10). In this other effort, the value of A was deduced to be 0.33 for all of three alloys, and, not surprisingly, the measured coarsening rates for LSHR and ME3 (having similar alloy and γ′ compositions) were identical. An inspection of the compositions of IN-100/René 88 and the various third-generation alloys (e.g., Tables 1 and 2) suggests that the tantalum addition is the differentiating element which plays a critical role in reducing the rate of diffusion which controls coarsening and likely the kinetics of precipitate nucleation and growth. In the latter regard, it was shown in reference [50] that A = 0.33 provides excellent predictions of the size and number density of secondary γ′ developed during continuous cooling of LSHR following supersolvus solution treatment.

Despite the generality of the present findings regarding the effective diffusivity, a word of caution is in order. That is to say, the companion effort [58] has shown that calculations assuming bulk-diffusion control, as embodied in Eq. (10), overestimate the measured coarsening rate by approximately a factor of five for temperatures below approximately 1050 K or those typical of service conditions for PM nickel-base superalloys. At such temperatures, the coarsening mechanism changes from bulk-diffusion control to more-sluggish trans-interface-diffusion control [64].

Summary

Engineering methods for determining the input parameters for simulating nucleation, growth, and coarsening of γ′ in PM nickel-base superalloys have been formulated and validated for IN-100, René 88, and LSHR. The simplicity of the techniques makes them excellent candidates for inclusion in ICME “best-practice” documents. The approaches can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Solvus approach curve and phase compositions: The solvus approach curve can be fit by an analytical expression with three parameters—the solvus temperature per se, the maximum amount of γ′ based on the atomic fractions of γ′-forming elements, and a parameter Q used to fit the expression to a relatively small number of experimental measurements. The value of Q lies in the range between 60 and 75 kJ/mol. Phase compositions can be determined using conventional phase-extraction methods and subsequent chemical analysis of each phase.

-

2.

The chemical free energy associated with the γ → γ + γ′ transformation is readily determined from specific-heat/solvus temperature measurements or classical expressions from solution thermodynamics for the Ni-Cr pseudo-binary. The latter method is suitable for arbitrary matrix compositions, solution temperatures (super- or subsolvus), and complex cooling paths.

-

3.

The γ-γ′ interface energy σ is easily determined from the temperature at the onset of nucleation, simple parametric calculations of the nucleation rate (in which σ is varied), and the specification of an “operational” critical nucleation rate (e.g., 1/μm3s). The onset temperature is readily determined from careful on-cooling measurements of the specific heat. The value of σ for PM superalloys analyzed in this work has been found to lie in a narrow window between 23 and 25 mJ/m2.

-

4.

An effective diffusivity based on the impurity diffusion for chromium in nickel and a scaling factor “A” independent of temperature can be readily determined from static-coarsening measurements at several temperatures. The scaling factor has been found to be approximately 0.8 for IN-100 and René 88 and 0.33 for third-generation PM superalloys which contain tantalum (i.e., LSHR, ME3, and Alloy 10).

List of symbols

A, scaling factor for effective diffusivity

a o, lattice parameter

C, concentration

C γ,C γ′, equilibrium solute concentration in the γ matrix, γ′ precipitate

C p, specific heat

C*, total atomic fraction of γ′-forming elements

D, diffusivity

D eff, effective diffusivity

D B, impurity diffusivity of solute in nickel

f, volume fraction of precipitate

J, nucleation rate

J o, steady-state nucleation rate

K MLSW, volume-fraction modified LSW coarsening-rate constant

k B, Boltzmann’s constant

Q, fitting parameter for solvus approach curve

r, precipitate radius

r*, critical radius of precipitate

R, gas constant

T, absolute temperature

T γ′, γ′ solvus temperature

t, time

V M, molar volume

v, activity coefficient

w, volume-fraction function in coarsening-rate equation

∆G*, chemical free energy of transformation

∆G p, misfit energy

∆H, enthalpy of formation of γ′

∆S, entropy of formation of γ′

Ω, supersaturation

σ, matrix-precipitate interface energy.

τ, incubation time

Notes

Heterogeneous precipitation of γ′ at γ grain boundaries, which can play a role in creep and dwell fatigue during service, is not treated herein.

References

Donachie MJ (ed) (1984) Superalloys: source book. ASM International, Materials Park

Forbes Jones RM, Jackman LA (1999) The structural evolution of superalloy ingots during hot working. JOM 51(1):27–31

Muzyka DR (1979) Physical metallurgy and effects of process variables on the microstructure of wrought superalloys. In: Abrams H, Maniar GN, Nail DA, Solomon HD (eds) MiCon 78: optimization of processing, properties, and service performance through microstructural control, ASTM STP 672. American Society for Testing and Materials, Philadelphia, pp 526–546

Doherty RD (1996) Diffusive phase transformations in the solid state. In: Cahn RW, Haasen P (eds) Physical Metallurgy, North-Holland Publishers, Amsterdam, ch. 15.

Martin JW, Doherty RD, Cantor B (1997) Stability of microstructure in metallic systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Turnbull D (1956) Phase changes. In: Seitz F, Turnbull D (eds) Solid-state physics, vol 3. Academic Press, New York, pp 226–306

Kelly A, Nicholson RB (1963) Precipitation hardening. Prog Mat Sci 10:151–391

Russell KC (1970) Nucleation in solids. In: Phase transformations. ASM, Metals Park, OH, pp 219–268

Christian JW (1975) The theory of transformations in metals and alloys, 2nd edn. Pergamon Press, Oxford

Russell KC (1980) Nucleation in solids: the induction and steady-state effects. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 13:205–318

Haasen P, Gerold V, Wagner R, Ashby MF (1984) Decomposition of alloys: the early stages. Pergamon Press, Oxford

Aaronson HI, LeGoues FK (1992) An assessment of studies on homogeneous diffusional nucleation kinetics in binary metallic alloys. Metall Trans A 23:1915–1945

Carslaw HS, Jaeger JC (1959) Conduction of heat in solids. Oxford University Press, London

Aaron HB, Fainstein D, Kotler GR (1970) Diffusion-limited phase transformations: a comparison and critical evaluation of the mathematical approximations. J Appl Phys 41:4404–4410

Lifshitz IM, Slyozov VV (1961) The kinetics of precipitation from supersaturated solid solutions. J Phys Chem Solids 19:35–51

Wagner C (1961) Theorie der alterung von niederschlägen durch umlösen (Ostwald‐reifung). Zeit Elektrochem 65:581–591

Ardell AJ (1972) The effect of volume fraction on particle coarsening: theoretical considerations. Acta Metall 20:61–71

Brailsford AD, Wynblatt P (1979) The dependence of Ostwald ripening kinetics on particle volume fraction. Acta Metall 27:489–497

Voorhees PW, Glicksman ME (1984) Solution to the multi-particle diffusion problem with applications to Ostwald ripening—I. Theory. Acta Metall 32:2001–2011

Voorhees PW, Glicksman ME (1984) Solution to the multi-particle diffusion problem with applications to Ostwald ripening—II. Computer simulations. Acta Metall 32:2013–2030

Calderon HA, Voorhees PW, Murray JL, Kostorz G (1994) Ostwald ripening in concentrated alloys. Acta Metall Mater 42:991–1000

Umantsev A, Olson GB (1993) Ostwald ripening in multicomponent alloys. Scripta Metall Mater 29:1135–1140

Morral JE, Purdy GR (1994) Particle coarsening in binary and multicomponent alloys. Scripta Metall Mater 30:905–908

Kuehmann CJ, Voorhees PW (1996) Ostwald ripening in ternary alloys. Metall Mater Trans A 27:937–943

Wendt H, Haasen P (1983) Nucleation and growth of γ′ precipitates in Ni-14 at.%Al. Acta Metall 31:1649–1659

Xiao SQ, Haasen P (1991) HREM investigation of homogeneous decomposition in a Ni-12 at.%Al alloy. Acta Metall Mater 39:651–659

Sudbrack CK, Yoon KE, Noebe RD, Seidman DN (2006) Temporal evolution of the nanostructure and phase compositions in a model Ni-Al-Cr alloy. Acta Mater 54:3199–3210

Sudbrack CK, Noebe RD, Seidman DN (2007) Compositional pathways and capillarity effects during isothermal precipitation in a nondilute Ni-Al-Cr alloy. Acta Mater 55:119–130

Rougier L, Jacot A, Gandin CA, Napoli PD, Thery PY, Ponsen D, Jaquet V (2013) Numerical simulation of precipitation in multicomponent Ni-Base alloys. Acta Mater 61:6396–6405

Wlodek ST, Kelly M, Alden DA (1996) The structure of René 88DT. In: Kissinger RD, Deye DJ, Anton DL, Cetel AD, Nathal MV, Pollock TM, Woodford DA (eds) Superalloys 1996. TMS, Warrendale, pp 129–136

Furrer DU (1999) Microstructure and mechanical property development in alloy U720LI. DEng Thesis, University of Ulm, Ulm

Furrer DU, Fecht HJ (1999) γ′ formation in superalloy U720LI. Scripta Mater 40:1215–1220

Gabb TP, Backman DG, Wei DY, Mourer DP, Furrer DU, Garg A, Ellis DL (2000) γ′ formation in a nickel-base disk superalloy. In: Pollock TM, Kissinger RD, Bowman RR, Green KA, McLean M, Olson S, Schirra JJ (eds) Superalloys 2000. TMS, Warrendale, pp 405–414

Jou HJ, Voorhees PW, Olson GB (2004) Computer simulations for the prediction of microstructure/property variation in aeroturbine disks. In: Green KA, Pollock TM, Harada H, Howson TE, Reed RC, Schirra JJ, Walston S (eds) Superalloys 2004. TMS, Warrendale, pp 877–886

Olson GB, Jou HJ, Jung J, Sebastian JT, Misra A, Locci I, Hull D (2008) Precipitation model validation in 3rd generation aeroturbine disc alloys. In: Reed RC, Green KA, Caron P, Gabb TP, Fahrmann MG, Huron ES, Woodard SA (eds) Superalloys 2008. TMS, Warrendale, pp 923–932

Wu K, Zhang F, Chen S, Cao W, Chang YA (2008) A modeling tool for the precipitation simulations of superalloys during heat treatments. In: Reed RC, Green KA, Caron P, Gabb TP, Fahrmann MG, Huron ES, Woodard SA (eds) Superalloys 2008. TMS, Warrendale, pp 933–939

Wen Y, Simmons JP, Shen C, Woodward C, Wang Y (2003) Phase-field modeling of bimodal particle size distributions during continuous cooling. Acta Mater 51:1123–1132

Wang JC, Osawa M, Yokokawa T, Harada H, Enomoto M (2007) Modeling the microstructural evolution of Ni-base superalloys by phase field method combined with CALPHAD and CVM. Comp Mater Sci 39:871–879

Simmons JP, Wen Y, Shen C, Wang Y (2004) Microstructural development involving nucleation and growth phenomena simulated with the phase field method. Mater Sci Eng A365:136–143

Wen Y, Lill JV, Chen SL, Simmons JP (2010) A ternary phase-field model incorporating commercial CALPHAD software and its application to precipitation in superalloys. Acta Mater 58:875–885

Kitashima T, Harada H (2009) A new phase-field method for simulating γ′ precipitation in multicomponent nickel-base superalloys. Acta Mater 57:2020–2028

Kampmann L, Kahlweit M (1970) On the theory of precipitation II. Berichte der Bunsen-Gesellschaft Physikalische Chemie 94:456–462

Perez M (2005) Gibbs-Thomson effects in phase transformations. Scripta Mater 52:709–712

Grong O, Shercliff HR (2002) Microstructural modelling in metals processing. Prog Mat Sci 47:163–282

Cao W, Chen S-L, Zhang F, Wu K, Yang Y, Chang YA, Schmid-Fetzer R, Oates WA (2009) PANDAT software with PanEngine, PanOptimizer and PanPrecipitation for multi-component phase diagram calculation and materials property simulation. Calphad 33:328–342

Dyson BF (2001) Predicting creep behavior in commercial precipitation-strengthened alloys. In: Proceedings Euromat 2001, Remini, Italy. (CD ROM).

Payton EJ (2009) Characterization and modeling of grain coarsening in powder-metallurgical nickel-base superalloys. PhD Dissertation, the Ohio State University, Columbus, OH USA.

Gabb TP, Garg A, Ellis, DL (2004) Microstructural evaluations of baseline HSR/EPM disk alloys. Report NASA/TM-2004-213123, NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, OH USA.

Mao J, Chang K-M, Furrer D (2000) Quench cracking characterization of superalloys using fracture mechanics approach. In: Pollock TM, Kissinger RD, Bowman RR, Green KA, McLean M, Olson S, Schirra JJ (eds) Superalloys 2000. TMS, Warrendale, PA, pp 109–116

Semiatin SL, Kim S-L, Zhang F, Tiley JS (2015) An investigation of high-temperature precipitation in powder-metallurgy, gamma/gamma prime nickel-base superalloys. Metall Mater Trans A 46:1715–1730

Larsen R, Goerz T (2015) Thermophysical properties of three nickel alloys (Report TPRL 5287). Thermophysical Properties Research Laboratory, West Lafayette, IN

Larsen R (2015) Specific heat of three nickel alloys (Report TPRL 5329, Rev A). Thermophysical Properties Research Laboratory, West Lafayette, IN

Larsen R (2015) Specific heat of one nickel alloy (Report TPRL 5370). Thermophysical Properties Research Laboratory, West Lafayette, IN

Gabb TP, Gayda J, Telesman J, Kantzos PT (2005) Thermal and mechanical property characterization of the advanced disk alloy LSHR. Report NASA/TM-2005-213645, NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, OH USA.

Robson JD, Jones MJ, Prangnell PB (2003) Extension of the N-model to predict competing homogeneous and heterogeneous precipitation in Al-Sc alloys. Acta Mater vol 51:1453–1468

Booth-Morrison C, Weninger J, Sudbrack CK, Mao Z, Noebe RD, Seidman DN (2008) Effects of solute concentrations on kinetic pathways in Ni-Al-Cr alloys. Acta Mater 56:3422–3438

Nesbitt JW, Heckel RW (1987) Interdiffusion in Ni-Rich, Ni-Cr-Al alloys at 1100 and 1200 °C: part I. Diffusion paths and microstructures. Metall Trans A 18:2061–2073

Dayananda MA (1989) Multicomponent diffusion studies in selected high-temperature alloy systems. Mater Sci Eng A121:351–359

Semiatin SL, Shank JM, Saurber WM, Pilchak AL, Ballard DL, Zhang F, Gleeson B (2104) Alloying-element loss during high-temperature processing of a nickel-base superalloy. Metall Mater Trans A 45:962–979

Campbell CE, Zhao JC, Henry MF (2004) Comparison of experimental and simulated multicomponent Ni-Base superalloy diffusion couples. J Phase Equil Diff 25:6–15

Karunaratne MSA, Cox DC, Carter P, Reed RC (2000) Modelling of the microsegregation in CMSX-4 superalloy and its homogenization during heat treatment. In: Pollock TM, Kissinger RD, Bowman RR, Green KA, McLean M, Olson S, Schirra JJ (eds) Superalloys 2000. TMS, Warrendale, PA, pp 263–272

Payton EJ, Picard R, Saurber A, Semiatin SL (2015) Unpublished research. Air Force Research Laboratory, Wright-Patterson Air Force base, OH USA.

Gabb TP, Garg A, Gayda J, Johnson D, Kang E, Locci I, MacKay RA, Rogers R, Sudbrack CK, Semiatin SL (2015) Comparison of γ-γ′ coarsening response of three powder metal disk alloys. Report NASA/TM-2016, NASA Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, OH USA, in press.

Ardell AJ, Ozolins V (2005) Trans-interface diffusion-controlled coarsening. Nat Mater 4:309–316

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of the in-house research of the Metals Branch of the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Materials and Manufacturing Directorate. The support and encouragement of the Laboratory management is greatly appreciated. Technical discussions with T.P. Gabb and C.K. Sudbrack (NASA Glenn Research Center) are also gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SLS led the R&D and developed the theoretical analysis methods. FZ performed the thermodynamic modeling including the determination of thermodynamic factors. RL and LAC developed the test techniques and data analysis methods for determining the on-cooling specific heat and pertinent transformation temperatures. DUF guided the definition of the program scope and its ICME application and mentored the other team members. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://doi.org/creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Semiatin, S.L., Zhang, F., Larsen, R. et al. Precipitation in powder-metallurgy, nickel-base superalloys: review of modeling approach and formulation of engineering methods to determine input data. Integr Mater Manuf Innov 5, 41–60 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40192-016-0046-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40192-016-0046-3