Abstract

In this paper we examine nominal earnings flexibility in Ireland during the Great Recession. The Irish case is particularly interesting because it has been one of the countries most affected by the crisis. Using tax return data that are free of reporting error and cover the entire population of workers, we find a substantial degree of downward nominal wage flexibility in Ireland in the pre-crisis period. Furthermore, we observe a significant change in wage dynamics since the crisis began. It was only after the peak crisis period that pay freezes became a feature of the Irish wage change distribution.

JEL Classification: J31, J38, D31

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The issue of whether wages are rigid or flexible is one that has been central to macroeconomics for many years.Footnote 1 However, many attempts to establish the extent of wage rigidity empirically have been hampered by small samples or measurement error. Moreover, results relating to earlier periods may not be relevant in the context of the large macroeconomic shocks that have hit many countries in recent years. In this paper we examine nominal wage flexibility in Ireland in the build up to and during the Great Recession, and at the beginning of the recovery. We do this using tax return data that are free of reporting errors and cover the entire population of workers.

The Irish economy provides an interesting setting for examining the flexibility of wages. After a period of very rapid growth from 1994 to 2007, when the average annual GDP growth rate was over 7%, the economy collapsed and the average growth rate over 2008–2010 was −3.1%. This was followed by a weak recovery, with average growth of 0.9% in 2011–2013. These growth figures were reflected in the unemployment rate, which had been relatively stable at 4–5% for most of the early 2000s but rose dramatically from 4.9% at the start of 2008 to 13.0% by the end of 2009. It then continued to rise further to its peak of 15.1% in early 2012, dropping to 12.1% by the end of 2013. Annual inflation averaged 3.8% in the period from 1994 to 2008 but was negative in 2009 (−4.5%) and 2010 (−1%), returning to positive values averaging 1.5% in 2011–13. Given these substantial changes in the macroeconomic environment, and the general flexibility of the Irish labour market (Andranik, 2008), it is useful to examine the extent to which wages responded during this period. This is particularly important given the conflicting views of wage adjustment in Ireland among leading policy makers. In a recent address to the 2014 Annual Central Bank Symposium, ECB President Mario Draghi attributes the recent diverging performances of the Irish and Spanish labour markets in part to the fact that “Ireland entered the crisis with a relatively flexible labour market …[In addition] in Ireland, downward wage adjustment began already in the fourth quarter of 2008 and proceeded more quickly [than Spain].” These conclusions are based on measures of aggregate wage changes for all workers, public and private sector combined. In contrast to the view held by Mr. Draghi, the Irish Minister for Finance is on the record citing nominal wage rigidity as an issue for the Irish economy. In a letter dated 19 December 2013 addressed to the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council, Minister Noonan states “...that potential output is particularly difficult to measure during spells of nominal wage rigidity such as that currently experienced in Ireland.”Footnote 2 However, no evidence is provided for this assertion.

In this paper we look at nominal wage changes over the pre-crisis and crisis periods using individual panel data. We find a significant degree of downward wage flexibility in the pre-crisis period, supporting the view that the Irish labour market is a flexible one. We also observe a significant response in wage change behaviour since the crisis began; the proportion of workers receiving earnings cuts more than trebled during the crisis. In addition, estimates of wage rigidity, which were already low before the crisis, fell further at the onset of the crisis, when unemployment was increasing dramatically.

The remainder of the paper is as follows. Section 2 summarises previous work relating to wage flexibility. Section 3 gives a brief overview of the Irish policy response to the crisis. Section 4 describes the datasets used in the analysis. Section 5 reports the main results of the paper, based on tax return data, while Section 6 reports some supplemental analyses carried out using the EU Survey of Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) data. Section 7 provides estimates of the degree of wage rigidity in Ireland. Section 8 concludes.

2 Literature review

There is a substantial body of research that uses microdata to examine the extent of wage flexibility. However, as of yet no general consensus has emerged. McLaughlin (1994) analyses Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) data and concludes that wages in the US are flexible; 17% of household heads who do not change employers face nominal wage cuts annually. However, these results have been challenged by a number of authors who argue that the extent of wage cuts in these data may be exaggerated by measurement error. Altonji and Devereux (2000) using both firm level personnel files and household survey data conclude that nominal wage cuts are rare once one accounts for measurement error. More recently Barattieri et al. (2010), using Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data and an alternative strategy to identify measurement error, reach a similar conclusion.

For the UK, Smith (2000) uses the 1991–1996 British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) to examine wage rigidity. Her initial results indicate that 9% of job stayers experience a zero nominal wage change from year to year and that 23% experience nominal wage reductions. To examine the consequences of measurement error, she uses the fact that the BHPS records whether respondents consulted their payslips when answering the wage question. In contrast to the results of Altonji and Devereux (2000) and Barattieri et al. (2010), she finds that measurement error in household surveys leads to an understatement of the extent of wage flexibility. The proportion of workers reporting no wage change falls from 9 to 6% when the sample is restricted to those who consult their payslip, a pattern she attributes to rounding error.

Evidence of wage changes for other countries is more limited. Dickens et al. (2007) report the results of the International Wage Flexibility Project, which analyses individual earnings in 16 countries. They find that on average 8% of workers receive nominal wage freezes, and in many countries wage cuts are rare. Ireland is unusual in that there is a lower incidence of wage freezes, and almost as many wage cuts are reported as would be if the wage change distribution were symmetric. They argue that the data used for their Irish analysis, the European Community Household Panel (ECHP), may explain the unusual Irish results as it contains fewer observations and more reporting errors than the datasets available for other countries.Footnote 3 Holden and Wulfsberg (2008) look at downward nominal wage changes across 19 OECD countries, reporting a significant reduction in the fraction of wage cuts prevented by downward nominal wage rigidity from 1970 to 1990. Comparing countries, they find that wage rigidity is relatively high in the Nordic and Southern European countries and lower in the Anglo (including Ireland) and Core (Central) European countries. They also report that wage rigidity is more prevalent when unemployment is low, union density is high and employment protection legislation more stringent. However, their analysis is based on industry level aggregate data averaged over many workers. Since they do not follow the same workers over time, their analysis may be affected by compositional bias. Solon et al. (1994) show that since low-skilled workers are more likely to lose jobs during a downturn, their low wages receive less weight in aggregate measures during recessions. Using aggregate wages therefore underestimates the pro-cyclicality of wages and correspondingly may overestimate the extent of nominal wage rigidities.

Böckerman et al. (2007) look at wage adjustment in Finland during the economic crisis suffered by that country in the early 1990s. From 1990–1993 output in Finland fell by 14%, and unemployment rose from 3 to 17%. These indicators were much worse than those recorded during the American Great Depression, though similar to the economic collapse suffered by Ireland from 2008–2010. Böckerman et al. (2007) report that during the downturn, nominal wage cuts ranged from 17-36% for manual workers in manufacturing. However, nominal cuts were almost completely absent for both service workers and non-manual workers in the manufacturing sector, indicating significant wage rigidity.

Recently researchers have begun to examine wage adjustment in the Great Recession. Blundell et al. (2014) examine payroll data from the National Employment Survey (NES) for the UK and find that the number of workers experiencing wage freezes increased from approximately 5% in 1990 to 12% in 2011. However, they find a significant degree of downward wage flexibility; throughout the 1990s and 2000s, almost 20% of stayers report a nominal wage cut. In contrast, Carneiro et al. (2014) find virtually no nominal wage cuts for job stayers in Portugal, even at the height of the crisis, reflecting the fact that such cuts are legally prohibited. Instead, they observe that wage freezes accounted for nearly 40% of all observations by 2009.

For the US, Elsby et al. (2015) use Current Population Survey (CPS) data to analyse wage changes from 1979–2011. They report several key features of the wage adjustment process in the US. First, there is always a significant spike at zero in the wage change distribution—between 6 and 20% of workers report exactly the same nominal wage in both years. Secondly, there is always a non-trivial fraction of workers (between 11 and 37%, depending on year and whether hourly paid or not) who report nominal wage reductions. Thirdly, while the zero spike increased during the Great Recession, the increase was not substantial. They consider the implications of these features of the wage change distribution and suggest that the high unemployment observed in recent years would have been nearly as high in a world with completely flexible wages. Notably, however, the authors report that an analysis of payroll-based data for three US states for the years of the Great Recession indicates that only 4% of workers had wage freezes, and 24% had nominal cuts. This suggests that the apparently greater degree of wage rigidity in the US than in the UK is largely the result of measurement error in the CPS.

Much of the research on Ireland in recent years has used firm-level survey data rather than individual-level data to examine the extent of downward wage rigidity. Du Caju et al. (2013) analyse a 2007/2008 survey of European firms and find that only 2% report having cut wages over the previous five years; the figure for Ireland was just 1%. Using the same data, Babecký et al. (2010) find that 10% of firms report having frozen base wages, with a corresponding figure for Ireland of 9%. Walsh (2012) uses the Earnings, Hours and Employment Costs Survey (EHECS) to examine wage changes during the recession and finds that 23% of establishments report cuts in average hourly earnings between 2008 and 2009, rising to 31% between 2009 and 2010.

3 The Irish labour market and the policy response to the crisis

As noted earlier, previous studies have found that the nature and magnitude of nominal wage adjustments depend on the level of unionisation, the level of employment protection and the nature of wage bargaining. Before the onset of the crisis, the Irish labour market was characterised as a very flexible one (Andranik, 2008). This view is supported by a recent OECD (2013) report that presents a review of Employment Protection Legislation for 43 countries. Employment protection in Ireland is low across a range of dimensions, including procedural inconvenience, notice, severance pay and difficulty of dismissal. Based on a composite measure of these factors, only 6 of the 43 countries analysed (US, Canada, UK, New Zealand, Hungary and Switzerland) have weaker employment protection legislation.

On the other hand, union density in Ireland is higher than the OECD average, albeit falling over time. The latest OECD figures put union density in Ireland at 31.2% in 2012 compared to an OECD average of 17.1%.Footnote 4 The rate of union density in Ireland has fallen from 38.7% in 1999. Strobl and Walsh (2009) analyse this trend in detail and find that the fall reflects a decline in the underlying probability of becoming a union member rather than a compositional change in the workforce. The low levels of employment protection and relatively high levels of unionisation in Ireland are expected to have opposing effects on the extent of wage rigidity (Holden and Wulfsberg, 2008).

From 1987–2009 Ireland operated a national system of pay agreements. Under this system unions, government and participating employers bargained at a national level over wage increases. These agreements were always rigidly adhered to by the public sector. However, for private sector employers, adherence was effectively voluntary, and by the start of our sample period, the agreements appear not to have been widely applied. In 2009, the national wage setting process was abandoned, having been put under pressure by austerity measures undertaken by the government in order to restore public finances. On the collapse of the agreements, employers’ organisations stated that they expected a period of enterprise-level bargaining to ensue.Footnote 5

As noted in the Introduction, Ireland was one of the countries worst affected by the Great Recession, with output falling by over 10% in real terms between 2008 and 2010 and unemployment more than doubling over the same period. The effects of the global recession felt elsewhere were compounded in Ireland by the bursting of a property bubble and the subsequent collapse of output and employment in construction-related sectors. Because bank lending was so highly concentrated in construction, Irish banks experienced huge losses and the government decided to guarantee all bank liabilities in 2008. However, continued falling tax revenue and exposure to bank liabilities resulted in the government deficit going from almost zero in 2008 to 13.9% in 2010 and to a remarkable 30.8% in 2011, when banking losses crystallised. As a result, yields in Irish bonds reached unsustainable levels in 2010, and the government sought and accepted a rescue package from the EU, ECB and IMF.

The crisis resulted in the government undertaking a severe programme of austerity measures, combining tax increases and expenditure cuts. As part of the expenditure cuts, the government set out to cut payroll costs in the public sector substantially by reducing staff and directly cutting pay. Pay rates in the public sector were initially reduced via a Pension Levy introduced in 2009 ranging from 5 to 10.5%. Further pay cuts of 5 to 10% were implemented in 2010. A third round of public sector pay cuts was implemented in 2013, affecting higher paid public sector workers; those earning more than €65,000 had their pay cut by between 5.5 and 10%, with bigger cuts applying to those on higher pay. In addition, there were increases in hours worked, the reduction or elimination of overtime rates, and lower pay scales for new entrants into professions such as teaching. However, it should be noted that automatic annual pay increases (‘annual increments’) continued to be paid to many public sector workers until 2013, when they were deferred.

The immediate aim of these measures was to reduce the government deficit. A longer-term aim was to effect an internal devaluation; as a member of the euro area, only cuts in labour and other costs could reduce real exchange rates. There was an expectation that the public sector wage cuts would have a demonstration effect on the private sector, and so contribute to the desired internal devaluation. However, aggregate data indicate stability in the wages of private sector workers since the onset of the crisis (Barrett and McGuinness, 2012; Bergin et al. 2012). This would suggest that Ireland has been unable to achieve the necessary internal devaluation through private sector wage reductions, perhaps indicating a substantial degree of wage rigidity. However, as acknowledged by the authors, aggregate data suffer from a number of drawbacks. First, as noted earlier, it is difficult to control for compositional changes in the workforce that have taken place during the crisis; if workers who have lost their jobs differ from those who continue to be employed then basing average wages only on the population of workers will be misleading (Solon et al., 1994). Secondly, even if the aggregate wage change is relatively small, this may be hiding substantial differences in wage adjustments across individuals. By following the earnings of individuals over time, we can address both these issues.

4 Data

Two datasets are used in the paper. Our main analysis is based on data taken from the Job Churn (JC) dataset, which is a longitudinal administrative dataset covering the years 2005–2013 that has been compiled by the Central Statistics Office (CSO). These data combine three elements. Data on annual income and weeks worked are provided by the tax authorities in respect of every worker who was an employee during that year. Information on workers’ age and sex are provided by the Department of Social Protection. Finally, data on the sector in which each firm operates and the enterprise’s ownership structure come from the CSO’s Central Business Register. Anonymised worker and firm identifiers are included in the dataset to allow longitudinal analysis.

There are several significant advantages to using the JC data to examine changes in earnings over time. Firstly, because they are administrative data based on tax returns, they are largely free from measurement error; it is a criminal offence to misreport workers’ earnings in these returns. Secondly, the data comprise the entire population of employees in Ireland, and so the number of observations is large enough to allow very detailed analysis of earnings changes; there are up to 3 million employment records in the JC data in any year, of which approximately 1.6-1.8 million workers are job stayers from year to year. Thirdly, since employers are obliged to file these returns for every worker, problems associated with non-response and attrition are absent from the data. Finally, the data cover the period from 2005 to 2013, allowing us to compare earnings dynamics before and during the crisis and to see the first effects of the recovery.

The earnings variable provided in the JC data also has several advantages. Earnings are defined as annual ‘reckonable’ income for the calendar yearFootnote 6; this is gross income from all sources including bonuses and taxable benefits-in-kind after pension contributions, which are not taxable, have been deducted.Footnote 7 The fact that irregular earnings are included is important because firms can adjust labour costs through these components as well as basic pay; for evidence on the widespread use of adjustments to non-core pay, see Babecky et al. (2012), Du Caju et al. (2013) and Dias et al. (2013). In addition, firms can react to labour market shocks by changing hours of work, so we believe that data on earnings are the most appropriate for capturing the flexibility firms have in adjusting costs. The fact that the income measure is net of pension contributions allows us to take into account the Public Sector Pension Levy, mentioned in Section 3 above. Since this levy reduces earnings and entails no compensating increase in pension entitlements, it has the same effect as a reduction in gross pay, but it does not register as such in household surveys that record gross earnings.

While the use of total reckonable earnings has its advantages, it also has some limitations. In macroeconomic models, an internal devaluation is typically modelled as a reduction in the hourly wage. Unfortunately, the JC data contain no information that would allow the calculation of an hourly wage; nor is it possible to distinguish between changes in core and non-core pay. For this reason, we supplement our primary analysis by using the Irish component of the EU-SILC for the years 2005–2011. In Ireland, EU-SILC data is collected using a dedicated survey of about 5,000 households who are interviewed annually.

In the EU-SILC data, we use two pay variables—annual income and hourly wages. In contrast to the JC data, annual income includes pension contributions but excludes overtime and bonus payments. Thus, comparing annual earnings in these two datasets allows us to consider the role of these components in earnings dynamics. The hourly wage variable is calculated based on income received in the last pay cheque and hours worked. A comparison of the annual and hourly wage variables in the EU-SILC allows us to consider the role of hours worked in explaining earnings changes.

All income variables in the EU-SILC were subject to careful cleaning by the CSO, using administrative and other sources. In addition, respondents were encouraged to check their payslips and whether they did or not was recorded. For these reasons, reporting error is likely to be less important in the EU-SILC than in the ECHP used by Dickens et al. (2007) and Knoppik and Beissinger (2009).

For both the JC and EU-SILC datasets, we focus on job stayers, those who remain with the same employer in successive years. In the JC data, job stayers may have changed roles even if they did not change employer, whereas in the EU-SILC data, job stayers exclude those who have changed roles. To focus on workers with a strong attachment to the labour market, for both datasets we restrict our samples to employees who had worked for the full year in each pair of years. In the JC data, we also exclude all workers who had multiple jobs. As noted earlier, there are no hours data available in the JC data, and so for ease of comparison, we include both part-time and full-time workers in the EU-SILC sample.

Because of the different wage-setting mechanisms that pertain in the public and private sectors, we supplement our overall analysis with separate examinations of these sectors. While there is no public sector identifier in the JC data, the enterprise’s NACE code and its ownership structure can be combined to give a good indication of which sector an individual works in. When defining public sector workers, we omit workers in commercial state enterprises to the extent possible. A more detailed description of the construction of the public-private sector identifier variable is given in the Data Appendix.

After imposing these restrictions, we have between 700,000 and 800,000 observations per year in the JC data, and approximately 800 to 1,500 per year in the EU-SILC data. Summary statistics for both the JC and EU-SILC data are given in the Data Appendix.

5 Main results: analysis using administrative job churn data

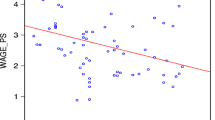

We begin our analysis by looking at the relationship between average earnings and unemployment. Figure 1 plots real and nominal average annual earnings against the unemployment rate over our sample period. The correlation between real earnings and unemployment over this period is −0.85 and −0.62 between nominal earnings and unemployment. Given the relatively short data period, the results are merely suggestive but nevertheless offer support for the pro-cyclicality of earnings in Ireland.

To analyze wage dynamics in more detail, we exploit the longitudinal nature of the JC data and look at annual nominal earnings changes for individuals for each pair of years between 2005 and 2013. By focusing on job stayers between successive years, we ensure that the composition of the sample is the same in each year pair. Therefore, the earnings growth rate between any two years is free of compositional changes. Although the restriction to job stayers between successive years overcomes the problem of composition bias in the year pair comparisons, this may not be sufficient to control for compositional biases over the longer run if the composition of stayers themselves is changing. We address this by conducting a supplementary analysis of a balanced panel of job stayers, the results of which we discuss later.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the annual earnings changes from 2005/06 to 2012/13. Following Ziliak et al. (2011), we calculate percentage earnings changes using the arc (midpoint) per cent change method; the key advantage of this method is that it is symmetric in gains and losses. The picture that emerges is of three distinct periods—pre-crisis, crisis onset and post-crisis stagnation. Column 2 shows the median percentage earnings change for each year pair. The growth in earnings in the pre-crisis period is evident in the numbers reported for 2005–2008, with median annual growth rates of between 4.5 and 6.1%. The impact of the crisis is clearly observed in the following period, with negative median wage changes of about 1% in 2008/09 and 2009/10. These wage changes are consistent with the relatively small changes in average earnings reported by Barrett and McGuinness (2012). Finally, in the post-crisis stagnation period, median pay changes returned to being positive, albeit slightly, with figures of +0.1% in the period from 2010/11 to 2012/13. It is worth noting that when we repeated this analysis for a balanced panel of job stayers—the group of workers who were stayers within the same firm over the entire data period—the results are very similar, indicating that changes in the composition of stayers themselves are not driving our findings.

As noted earlier, aggregate measures may hide important differences across individuals. Columns 3–5 report the percentage of workers receiving an earnings freeze, an earnings cut and an earnings rise; as is common in the literature, we classify a change of less than 0.1% as an earnings freeze. These data reveal substantial flexibility. Similar to Blundell et al. (2014) for the UK and Elsby et al. (2015) for the US and the UK, we find that a non-trivial fraction of Irish workers report nominal earnings reductions in each year. In the pre-crisis period, the percentage of workers experiencing earnings cuts ranged from 17 to 23%. In contrast to the US and the UK, this proportion increased substantially during the crisis, reaching a high of 55% in 2009/10, compared to 24% in the UK and 37% in the US. In the post-crisis stagnation period, the proportion experiencing cuts dropped substantially, to about 34%. However, this remains far above the pre-crisis norm.

Although these results illustrate significant wage reductions in response to the crisis, it is worth noting that the percentage experiencing earnings increases remained above 40% throughout the period. This compares to a figure of over 60% reported for the UK by Blundell et al. (2014).

Turning to wage freezes, the percentage of workers whose earnings did not change from year to year was less than 3% in the pre-crisis period and rose to 10.3% in 2011/12. Elsby et al. (2015) report that the percentage of nominal wage freezes in the UK over the period 2005–2011 ranges from 1.7 to 7.4%, findings that are similar to ours for the same period. For the US they find that the proportion of wage freezes in the CPS data is substantially larger, ranging from 17.6 to 19.5% for hourly paid workers and from 9.4 to 14.9% for non-hourly paid workers, although as noted above, these wage freeze figures drop substantially to 4% when payroll-based data are used.Footnote 8

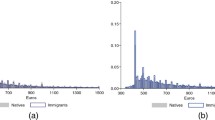

To look at these earnings changes in more detail, Fig. 2 shows the histograms of annual nominal earnings changes in each of the years. We include two lines on each graph—a solid line at zero, indicating a nominal earnings freeze, and a dashed line at the inflation rate for that year, corresponding to a real earnings freeze. In each year we observe a spike in the nominal earnings change distribution at zero, as discussed earlier. In addition to the spike at nominal zero, we also observe a spike near the inflation rate in the pre-crisis period. As we will see later in the paper, this spike applies only to public sector workers and is likely to reflect national pay agreements, which targeted the expected inflation rate and were strictly adhered to in this sector until 2008.Footnote 9 The shift to the left of the pay change distribution during the crisis is also evident from the graphs, as is the increase in mass to the left of zero in 2008/09 and 2009/10.

As well as the incidence of pay cuts and pay rises, it is also useful to examine the magnitude of these changes. These are reported in Table 2. Column 2 (3) shows the size of the median earnings cut (increase) for those receiving cuts (increases) over the period. As might be expected given the leftward shift of the wage change distribution, the median pay cut rose—albeit slightly—during the crisis onset years of 2008/2010, from 5 to 6%. However, in the post-crisis-stagnation period, the median pay cut fell in size to about 3.5%, which is lower than the pre-crisis level. The median pay rise also fell, from about 8% pre-crisis to 4–5% once the crisis occurred.

We next consider where along the distribution of earnings the downward adjustment in earnings identified above was most prevalent. To do this, we consider how the earnings changes varied by initial earnings levels. For both the pre-crisis and crisis period, we group individuals into earnings terciles at the start of the period and then consider median earnings changes within each of these terciles. The results are given in Table 3. Looking at the pre-crisis period, we see relatively small differences in earnings changes across the distribution, with earnings growth slightly higher for lower paid workers. The third column of the table shows that the earnings cuts during the crisis were highly progressive. The median pay change for those in the bottom tercile in 2008 who were in the same jobs in 2013 was still positive, though much lower than the pre-crisis period. However, the upper two terciles experienced earnings cuts over this period; the median pay changes were −0.5 and −5.0% for the middle and upper terciles respectively.

A major focus of policy discussion during the crisis centred on the relative wage adjustments in the public and private sectors. Table 4 presents earnings changes separately for these two sectors. Looking at the pre-crisis years, we see that earnings dynamics were similar in the two; between 15 and 25% experienced earnings cutsFootnote 10 and between 71 and 85% experienced earnings increases. As discussed earlier, a key government response to the crisis involved the imposition of a series of direct pay cuts in the public sector. Table 4 shows that 59% of public sector workers experienced an earnings cut in the 2008/09 period, increasing to 81% in 2009/10.Footnote 11 Furthermore, the magnitude of the cuts was substantial; the median earnings change was a cut of 6% in 2009/10. Although there were no legislated pay cuts in 2010/11 or 2011/12, 36 and 31% respectively of public sector workers experienced reductions in annual earnings in those years. The legislated pay cuts in 2013 for higher paid public sector workers are reflected in the rise in the proportion affected by pay cuts to 37% in 2012/13.

Table 4 also reveals a significant response to the crisis for private sector workers. The percentage experiencing earnings decreases rose from 19% in 2006/07 to 50% in 2008/09. The figures for 2009/10 and subsequent years fell year on year, but remained well above the pre-crisis levels. In each year of the crisis, the median earnings change in the private sector was approximately zero. However, this aggregate figure masks the heterogeneity of earnings responses to the crisis in the private sector.

The histograms reported in Figs. 3 and 4 for public and private sector workers respectively show these earnings dynamics in more detail. Looking at Fig. 3, we see marked differences in the public sector earnings change distributions before and after the crisis. In the pre-crisis period, there is a spike at roughly the inflation rate, coinciding with the settlements in the national wage agreements that were in operation in this period; this spike disappears during the crisis—during which time the national wage agreements were abandoned—and there is a clear shift to the left of the earnings change distribution for public sector workers. In addition, a strong spike at zero emerges for public sector workers in the post-crisis-stagnation period. The histograms for private sector workers are, for the most part, in keeping with the discussion for all workers; there is a persistent spike at zero that increases dramatically during the crisis, combined with a substantial increase in the proportion of workers experiencing earnings cuts at the height of the crisis. However, the spike at the inflation rate in the pre-crisis period is absent in the private sector graphs, which is consistent with the anecdotal evidence that private sector employers did not adhere to national wage agreements.

Since we know that the legislated public sector cuts were progressive, it is interesting to return to the issue of progressivity by sector. Table 5 repeats the distributional analysis of Table 3 by sector. The results show that the progressivity of pay cuts during the crisis period is largely driven by the pattern of pay cuts in the public sector. Before the crisis, the pattern of pay changes at the top of the public and private earnings distributions was very similar, with workers in the top terciles experiencing earnings increases of approximately 15% in both sectors. However, the progressivity of earnings cuts was much more evident in the public sector during the crisis. The median cumulative pay change between 2008 and 2013 was positive in all terciles of the distribution in the private sector, with little difference between the middle and top terciles. The median earnings change was also positive for the bottom tercile of public sector workers and similar to that recorded in the private sector. In contrast, public sector workers in the middle tercile of the earnings distribution recorded a median cumulative pay cut of 5.4% over this period, while public sector workers in the top tercile recorded a median cut of 11.9%.

The very large number of observations in the JC data permits a more detailed breakdown of the earnings changes, classifying workers by broad industrial sector. We begin by looking at the incidence of year-on-year earnings cuts, increases and freezes. The results are given in Fig. 5. As similar patterns were evident in each of the pre-crisis year pairs, we only present the graph for 2005/06, which shows that pay rises dominate in every sector; approximately 80% of workers in each sector receive earnings increases. The figures for the crisis period reveal an increase in the incidence of earnings cuts in all sectors. However, sectoral differences are apparent. The impact of the crisis on the Construction sector is particularly evident from 2008–2011, although pay freezes appeared to take over from pay cuts in this sector during the post-crisis-stagnation period. Earnings decreases were widespread in Public Administration & Education, in Health and in Utilities (gas, electricity and water) in the 2008–2001 period. In Finance and Insurance, which along with Construction and Real Estate was at the centre of the occurrence of the crisis, earnings cuts were particularly prevalent in 2008/09, but were not noticeably more prevalent than in other sectors in subsequent years.

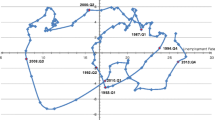

The year-on-year earnings changes presented so far do not allow us to examine cumulative pay changes for a given individual. For example, it is possible that workers whose earnings have been cut in one year have had those pay cuts reversed in subsequent years, resulting in small cumulative pay changes over several years. To address this issue, we examine median cumulative pay changes separately for the pre-crisis and crisis periods by industrial sector. The results are given in Fig. 6. Looking at the pre-crisis period, we see substantial pay growth in 2005–2008 for all workers, with a median of 16.5%. In contrast, the median cumulative pay change from 2008–2013 was −1.2%, indicating that pay cuts were not typically reversed. However, Fig. 6 also indicates significant variation across sectors, with pre-crisis cumulative increases for job stayers ranging from a median of 13.3% in Construction to 22.8% in Finance & Insurance. Over the years since the crisis occurred, the median cumulative pay change was negative in about half of the sectors. Construction was the hardest hit, with a median cumulative earnings change of −7.9% between 2008 and 2013. It is notable that the Finance & Insurance sector, which experienced the biggest increase in median pay in the pre-crisis period, has been one of the least affected during the crisis. This finding echoes that of Bell and Van Reenan (2014) for the UK.

6 Further analysis using EU-SILC data

As noted earlier, changes in the annual reckonable income measure reported in the JC data may reflect changes in non-core pay, in pension contributions or in hours worked, as well as changes in the rates of pay. To examine these issues in more detail, we use the EU-SILC survey data.Footnote 12 The annual earnings variable in the EU-SILC data excludes non-core pay and includes pension contributions. A comparison of annual earnings dynamics from the EU-SILC and the JC data therefore allows us to assess the role of these issues in earnings changes. The EU-SILC data also include an hourly wage variable, which allows us to consider the role of hours in earnings changes.

We begin by comparing the dynamics for annual JC and EU-SILC earnings. Table 6 shows the results from the EU-SILC, alongside the results from the JC reproduced from Table 1. Looking first at the median changes, we see that with the exception of 2008/09, both datasets give very similar aggregate results. In both datasets, earnings growth falls from about 6% in 2005/06 to about 4.5% in 2007/08, is negative in 2009/10 and small and positive in 2010/11. The only difference between the two series arises in 2008/09, where the median rise in earnings in the EU-SILC data was 4.4%, compared to a fall of 0.6% in the JC data. This difference is explained by the Public Sector Pension Levy introduced in 2009 and discussed earlier. The trends in the percentages receiving earnings freezes, cuts or increases are also similar across the two datasets. Both datasets show a rise in the percentage receiving earnings cuts and a fall in the percentage receiving earnings increases during the crisis. The similarity of the two sets of results—apart from the 2009 pension levy—suggests that changes to non-core pay and discretionary pension contributions were not important determinants of earnings dynamics.

It has been well documented (e.g., Walsh 2012) that firms in Ireland responded to the crisis in part by adjusting hours of work, which would be reflected in changes in annual earnings with no corresponding change in hourly pay. Since the EU-SILC provides information on hours worked, it allows us to examine dynamics in hourly pay. The results are given in Table 7; to allow comparison, we reproduce the EU-SILC results on annual earnings from Table 6 in the first five columns. The major features of wage dynamics reported earlier for annual earnings using both the JC and EU-SILC data are still evident when we use hourly pay. The percentage of workers receiving a cut in hourly pay increases from below 30% in 2005/06 to about 48% in 2009/10, as the labour market reacted significantly to the crisis. The most notable difference between the two series is the fact that in all years, a higher percentage of workers report a pay freeze when using hourly pay as opposed to annual pay. Furthermore, this difference increases substantially during the crisis period, supporting the view that firms responded to the crisis by adjusting hours as well as base pay. Nevertheless, the percentage of workers receiving pay freezes when hourly wages are used is still relatively low by international standards in the years immediately following the onset of the crisis.

7 Measurement of wage rigidity

So far, we have examined the proportion of freezes and cuts in the earnings change distribution as indicators of wage flexibility. In this final section of the paper we turn to the construction of a measure of wage rigidity, which attempts to identify the proportion of desired cuts that are prevented from occurring. Many measures of rigidity have been proposed.Footnote 13 These include the ‘skewness location approach’ (McLaughlin, 1994), the ‘histogram location approach’ (Kahn, 1997) and the ‘symmetry approach’ (Card and Hyslop, 1997; Montes and Ehrlich, 2013). These alternatives identify wage rigidity either through shifts in the location of wage change histograms or by assumptions on the form of the counterfactual distribution that would be observed in the absence of rigidity. However, all of these measures require that the highest wage change affected by rigidity is smaller than the median of the counterfactual distribution. The economic crisis in Ireland was so severe that in a number of years the median observed pay change was negative, thus violating this requirement.Footnote 14 Furthermore the limited variation in the location of the wage change histogram in our data poses a problem for location-based approaches.

Dickens et al. (2007) propose a simple measure of downward nominal wage rigidity that is not dependent on wage change medians being positive or on large variation in the location of the distribution. This measure is based on the assumption that everyone who had a nominal freeze would have had a wage cut in the absence of wage rigidity. The measure is defined simply as the ratio of the proportion of workers receiving freezes to the proportion receiving either cuts or freezes. This measure provides a consistent measure of wage rigidity, provided all desired wage cuts that are not enacted are recorded as wage freezes and that wage rigidity does not affect firms wishing to offer pay increases.

In Dickens et al.’s (2007) cross country comparison, the average degree of downward rigidity is 28%. Their average for Ireland for the period 1993 to 2001 is 4%, the lowest of all countries covered, but as noted earlier, they express reservations about the Irish data. We calculate this measure using the JC dataFootnote 15 and the results are reported in Table 8. Rigidity was 16–18% in the pre-crisis period. Although these figures are substantially higher than those reported by Dickens et al. (2007) for Ireland, they are still low relative to many of the other countries reported in their analysis. Our estimates are similar to their results for the UK and only slightly higher than those for Denmark, France and Belgium, which are the three most flexible countries in their analysis after Ireland.

At the onset of the crisis, measured downward rigidity fell substantially to 10.1% in 2008/09 and then rose slightly to 12.7% in 2009/10. The finding that wage rigidity fell with the onset of the crisis is consistent with previous work that found that cyclical downturns relax nominal wage rigidity (Beissinger and Knoppik, 2001). The predominant explanation for downward wage rigidity is that employers avoid reducing wages because of the effect on morale. Bewley (1999) examined wage rigidity in the US during the recession of 1991–1992 and found that managers used wage cuts only in circumstances where the firm faced serious problems. Since the economic crisis in Ireland caused serious problems for many firms, it is plausible that downward nominal wage rigidity would be lessened in these years. In addition, Gordon (1996), in his comment on Akerlof et al. (1996) on the impact of wage rigidity in a low-inflation environment, suggests that nominal wage reductions would no longer be seen as unfair. The fact that inflation dropped and then turned negative during the crisis might also explain the fall in downward nominal wage rigidity.

However, our findings for the latter part of the period suggest that this reduction in rigidity was temporary. By the end of our sample period, at which time Ireland was still experiencing significant economic difficulties, estimated rigidity had significantly surpassed its pre-crisis level and was about 27% in 2011/12 and 2012/13. Since the Dickens et al. (2007) measure is identified from the spike at zero in the wage change distribution, it is useful to consider the source of the spike in 2010/11 in more detail. One possibility is that firms in Ireland found pay cuts difficult to implement after two or more consecutive years of cuts, in which case the increased spike comes from the left-hand side of the wage change distribution. About one third of job stayers had pay cuts in both 2008/09 and 2009/10. It is plausible that resistance to additional pay cuts would have grown in subsequent years.

An alternative possibility is that the proportion of freezes is rising because firms who would otherwise give pay rises are reluctant to do so because wage rigidity would prevent reversals of these rises in subsequent years (Elsby, 2009). In this case, the increased spike comes from the right-hand side of the distribution. We use the distributions of earnings changes for 2008/09 and 2010/11, shown in Fig. 7, to assess these explanations. Comparing the two distributions, it is apparent that the right side of the distribution is similar in both years and that the increase in rigidity in 2010/11 is being drawn largely from the left side of the distribution, with some counterfactual wage cuts being swept up to zero. Although only suggestive, this analysis favours the explanation that the increased spike in the wage change distribution reflects missing pay cuts as opposed to missing pay rises.

8 Conclusions

A large body of macroeconomic research emphasises the role of wage rigidity in accounting for unemployment. However, attempts to measure wage flexibility have been hindered by small samples and measurement error in earnings data. In this paper we examine nominal wage flexibility in Ireland before and since the start of the Great Recession. Our primary analysis uses tax return data that are free from reporting errors and cover the entire population of workers. We supplement the analysis of these administrative data with an analysis of survey data that allow us to examine earnings dynamics in more detail

We find a significant degree of downward flexibility in both annual earnings and hourly wages in the pre-crisis period. We also observe a marked change in wage dynamics; the proportion of workers receiving earnings cuts more than trebled so that at the height of the crisis, over half of all workers were experiencing earnings decreases. In addition, we find that measured wage rigidity was low initially and fell substantially at the onset of the crisis.

Although results based on wage changes at the aggregate level suggest that wages did not respond to the crisis in Ireland, our results highlight the potential deficiencies of using aggregate data to assess the behaviour of labour markets over the business cycle. Focusing on individual wage changes, we show that wages responded dramatically to changing economic conditions. The extent to which this wage flexibility mitigated the employment effects of the shock to Ireland’s economy in 2008–2009 is a topic for future research.

Notes

For a discussion of the role of wage flexibility in alternative economic models see Gali (2013).

Italics added by the authors. The letter is available at http://www.finance.gov.ie/sites/default/files/letter%20from%20min%20to%20IFAC.pdf

The ECHP has also been used by Knoppik and Beissinger (2009) to develop a more formal model of wage rigidity.

Industrial Relations News, Issue no. 1, January 2010.

One complication that arises from the use of an annual earnings measure is that the number of pay days can vary for weekly paid workers because of the structure of the calendar. For instance workers who are paid weekly would have received 53 pay cheques in 2010 if paid on Fridays but only 52 in 2009 or 2011—resulting in a recorded earnings rise of 1.9% between 2009 and 2010 and a cut of 1.9% between 2010 and 2011 for workers whose weekly earnings were unchanged. We take account of this in calculating the wage rigidity measures discussed in Section 7.

There were no changes in the tax code over the period that would have led to spurious changes in earnings. We also examined EU-SILC data for evidence of systematic changes in pension contributions in response to earnings cuts, and found none.

Although it is not possible to account for hours changes in the JC data, we have conducted the same analysis as described in this section for a subset of male workers aged 30–50 on the basis that these workers have a low likelihood of voluntarily changing their hours of work. Results for this subset are very similar to the results for the full set of workers. This indicates that voluntary hours changes are not driving our results. We return to the issue of hourly wage changes when using the EU-SILC data in Section 6.

There are also notable spikes at roughly −2% and +2% in the later years; this reflects the distribution of pay days for weekly paid workers and the complication this causes for annual pay discussed in note 6.

The prevalence of earnings decreases in the pre-crisis period is somewhat surprising, particularly in the public sector, where announced pay changes were all positive. The JC data allows us to examine the frequency of earnings cuts by NACE sector for evidence of a pattern that might be explained by hours variability. In results not reported here, we see that even pre-crisis, earnings cuts were widespread in all areas of the public sector, not just in sectors where overtime pay is common and did not seem to vary substantially by gender as might be expected if wage variation was due to parental responsibility leading to hours variation. The EU-SILC data allows further consideration of issues of hours and non-core pay, and we return to these in Section 6.

Recall that annual increments continued to be paid to some public sector workers throughout our period.

In the reported results, we use all wage responses in the analysis. In order to assess the importance of measurement error, we follow Smith (2000) and also consider subsamples of workers who consulted their payslips before answering the wage question, which is likely to reduce measurement error in wages. Analysis of this payslip variable, which is only available from 2006, indicates that those who consulted their payslips were disproportionately public sector workers. Nevertheless, the results for these subsamples are similar to those reported in the text for the full sample.

When calculating the rigidity measure, we take account of the fact that the different numbers of pay days across years may result in some freezes being recorded as increases or decreases. In particular, we use the observed frequency of workers in small bins either side of −1.9% and +1.9% to impute the predicted frequency in the affected bin. The difference between the observed and predicted frequencies is added to the pay freezes in Table 1 when calculating the rigidity measure.

References

Akerlof GA, Dickens WT, Perry GL (1996) The macroeconomics of low inflation. Brookings Paper Econ Activ 1:1–76

Altonji J, Devereux P (2000) The extent and consequences of downward nominal wage rigidity. Res Labor Econ 19:383–431

Andranik T (2008) On the European readiness for flexicurity: empirical evidence with OECD/HBS methodologies and reform proposals, WIS Discussion paper no. 160

Babecký J, Caju PD, Kosma T, Lawless M, Messina J, Rõõm T (2010) Downward nominal and real wage rigidity: survey evidence from European firms. Scand J Econ 112:884–910

Babecky J, Du Caju P, Kosma T, Lawless M, Messina J, Room T (2012) How do European firms adjust their labour costs when nominal wages are rigid? Labour Econ 19:792–801

Barattieri A, Basu S, Gottschalk P (2010) Some evidence on the importance of sticky wages. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass

Barrett A, McGuinness S (2012) The Irish labour market and the great recession. CESifo DICE Report 10:27–33

Barwell RD, Schweitzer ME (2007) The incidence of nominal and real wage rigidities in Great Britain: 1978–98. Econ J 117:F553–F569

Bauer T, Bonin H, Goette L, Sunde U (2007) Real and nominal wage rigidities and the rate of inflation: evidence from West German micro data. Econ J 117:F508–F529

Beissinger T, Knoppik C (2001) Downward nominal rigidity in West German earnings, 1975–95. Ger Econ Rev 2:385–417

Bell B, Van Reenan J (2014) Bankers and their bonuses. Econ J 124:F1–F21

Bergin A, Kelly E, McGuinness S (2012) Explaining changes in earnings and labour costs during the recession. ESRI, Dublin

Bewley T (1999) Why wages don’t fall during a recession. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Blundell R, Crawford C, Wenchao J (2014) What can wages and employment tell us about the UK’s productivity puzzle? Econ J 124:377–407

Böckerman P, Laaksonen S, Vainiomäki J (2007) Who bears the burden of wage cuts? Evidence from Finland during the 1990s. Int J Manpow 28:100–121

Card D, Hyslop D (1997) Does inflation ‘grease the wheels of the labour market’? In: Romer C, Romer D (eds) Reducing inflation: motivation and strategy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 71–114

Carneiro A, Portugal P, Varejao J (2014) Catastrophic job destruction during the Portuguese economic crisis. J Macroecon 39:444–457

Deelen A, Verbeek W (2015) Measuring downward nominal and real wage rigidity - why methods matter., http://www.sole-jole.org/2015Deelen.pdf

Devicienti F, Maida A, Sestito P (2007) Downward wage rigidity in italy: micro-based measures and implications. Econ J 117:F530–F552

Dias D, Marques C, Martins F (2013) Wage rigidity and employment adjustment at the firm level: evidence from survey data. Labour Econ 23:40–49

Dickens WT, Goette L, Groshen EL, Holden S, Messina J, Schweitzer ME, Turunen J, Ward ME (2007) How wages change: micro evidence from the international wage flexibility project. J Econ Perspect 21:195–214

Du Caju P, Kosma T, Lawless M, Messina J, Room T (2013) Why firms avoid cutting wages: survey evidence form European firms, Central Bank of Ireland Research Technical Paper 03/RT/13

Elsby M (2009) Evaluating the economic significance of downward nominal wage rigidity. J Monetary Econ 56:154–169

Elsby M, Shin D, Solon G (2015): “Wage Adjustment in the Great Recession and Other Downturns: Evidence from the United States and Great Britain,” https://68088b26-a-62cb3a1a-s-sites.googlegroups.com/site/mikeelsby/documents/WagePaperAugust2014.pdf?attachauth=ANoY7cpxy2n1RGmEf_mkYMsAUQTRv0hPk1Q3OE3m0r45O1RojsF3lAnyOiKsVdZHd8WtSkb7jtz_cJXCMJcJ4Uuexj_LOaoRSMvj6jYS6RgJkh47a8mjFD6r_gJkXQGuPmVSF7DgwQPvl_u-DP9sJ270OPxfbPJ2jXj4RBAxftvi7mNCyUSvbOC8h7CBxOAUWUSXfJqzxpZcL8z_qgNkjnlZzdHEPTsGhT7BF0id4jxAPp3Bob0YJWk%3D&attredirects=0.

Gali J (2013) Notes for a new guide to Keynes (I): wages, aggregate demand and employment. Journal of the European Economic Association 11(5):973–1003.

Gordon RJ (1996) Comment on Akerlof, Dickens and Perry(1996). The Macroeconomics of Low Inflation, Brookings Paper on Economic Activity, 1., pp 60–66

Holden S, Wulfsberg F (2008). “Downward Nominal Wage Rigidity in the Oecd.,” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics. Volume 8, Issue 1, ISSN (Online) 1935-1690, DOI:10.2202/1935-1690.1651, April 2008.

Kahn S (1997) Evidence of nominal wage stickiness from microdata. Am Econ Rev 87:993–1008

Knoppik C, Beissinger T (2009) Downward nominal wage rigidity in Europe: an analysis of European micro data from the ECHP 1994–2001. Empir Econ 36:321–338

McLaughlin KJ (1994) Rigid Wages? J Monetary Econ 34:383–414

Montes J, Ehrlich G (2013) Wage rigidity and employment outcomes: evidence from German administrative data, University of Michigan Working Paper

OECD (2013) Protecting jobs, enhancing flexibility: a new look at employment protection legislation, OECD Employment Outlook, Chapter 2

Smith J (2000) Nominal Wage Rigidity in the United Kingdom. Econ J 110:C176–C195

Solon G, Barsky R, Parker JA (1994) Measuring the cyclicality of real wages: how important is composition bias? Q J Econ 109:1–25

Strobl E, Walsh F (2009) Recent trends in Trade Union membership in Ireland. Economic and Social Review, 40(1):117-138

Ziliak JP, Hardy B, Bollinger C (2011) Earnings volatility in America: evidence from Matched CPS. Labour Econ 18:742–754

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank participants at the NERI Labour Market Conference, Dublin, May 2013; the Irish Economic Association Conference, Limerick, May 2014; the Labour Markets During Crises Conference, Maynooth, July 2014; the European Economic Association Conference, Toulouse, August 2014; the Labour Markets Over the Business Cycle Conference at the Central Bank of Ireland, December 2014; the Irish Economy Conference, Dublin, January 2015 and at seminars at the Institute of Education, London and Trinity College Dublin for helpful comments. We also thank Ben Berstock, Berni Dunne, John Dunne and Mervyn Ó Luing for help in accessing the Job Churn data and Marion McCann for help with the EU-SILC data. The authors would like to thank the anonymous referee.

Responsible editor: Alan Barrett

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The IZA Journal of European Labor Studies is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The authors declare that they have observed these principles.

Authors’ details

Aedin Doris is a lecturer in Economics at Maynooth University - National University of Ireland Maynooth

Donal O’Neill is a professor of Economics at Maynooth University - National University of Ireland Maynooth and Research Fellow IZA, Bonn.

Olive Sweetman is a lecturer in Economics at the Maynooth University - National University of Ireland Maynooth

Data Appendix

Data Appendix

1.1 Construction of Public Sector Identifier

The public sector variable was constructed based on a combination of the legal form of the organisation, the NACE code and, in some cases, particular enterprise numbers. Details are as follows:

The first step required was the cleaning of the NACE codes attached to enterprises. This was necessary as in some cases, employment records of workers working for the same firm (as given by its enterprise code) had been assigned different NACE codes. Moreover, over time, some firms change their NACE codes; this is not necessarily due to error—if firms change their product mix, their NACE code should change—but it will cause complications if the sectoral composition of firms changes over time. For this reason, a two stage procedure to produce ‘corrected’ NACE codes was employed. In the first stage, within each year, the modal value of NACE over each employment record for a given enterprise was calculated, and within each establishment this NACE code was substituted for the recorded NACE code. In the second stage, the modal value of the NACE code for each enterprise over all years of data was calculated, and again, that modal value was used to replace the recorded value in the case of a discrepancy between the two.

Once a more consistent NACE code has been attributed to each employment record, it can be assigned as a public sector job (publicsect = 1), a private sector job (publicsect = 2) or a so called ‘semi-state’ company job (publicsect = 3). These were allocated as follows:

First, all employment records for whom the legal form of the job was ‘statutory body’ were classified as public sector. Next, employment records with the following NACE codes were classified as public sector: 6411; 8411–8430; 8520; 8531; 8532. Next, employment records with legal form not equal to ‘private limited company’ and with the following NACE codes were classified as public sector: 8542; 8610; 8690; 9101; 9102. Next, employment records with the following NACE codes were classified as semi-state: 0240; 0892; 3513; 4910; 4931; 5310. Next, employment records for the largest firms (in terms of employment) within each of the following NACE codes were classified as semi-state: 3511; 3523; 4939; 5223; 6020; 6512. Next, employment records for firms with NACE code 5222 and with legal form equal to ‘statutory body’ were reclassified as semi-state. Finally, the employment records of any firm that had a valid NACE code, a missing legal form value, and that had not been assigned a value for the public sector variable by the above procedure were classified as private sector.

1.2 Summary Statistics: Job Churn data

Tables 9 and 10 provide summary statistics for job stayers in the Job Churn data. The main difference between the workers included in the two tables is that in Table 10, which relates to our final sample, the job stayers work 52 weeks in each year of a year pair. In addition, workers with multiple records, and categories of workers in non-standard employment (such as government employment schemes) are excluded. Not surprisingly, individuals working 52 weeks a year have higher earnings than all job stayers. In addition they are more likely to be public sector workers. However, there is little difference in either the age or the gender profiles of the two samples. In both tables, there is a notable decline in the proportion of public sector workers in our sample in 2010 and a subsequent recovery in 2011. This is due to a combination of changes in employment in the two sectors and changes in the propensity to stay in the same job and to work 52 weeks in the two sectors.

Tables 11, 12, 13 above detail the earnings distribution for job stayers in our final sample, for all workers and by sector.

1.3 Summary Statistics: EU-SILC sample

Finally Table 14 provides summary statistics for our final sample of job stayers in the EU-SILC data. Workers in the EU-SILC sample are slightly older than the job stayers in the JC data and are also more likely to be public sector workers. Since the public sector variable in the EU-SILC data is based on self-reported status, it is not directly comparable with the public sector variable in the JC data. Similarly, as noted in the text, the measures of earnings differ between the two datasets and are not directly comparable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Doris, A., O’Neill, D. & Sweetman, O. Wage flexibility and the great recession: the response of the Irish labour market. IZA J Labor Stud 4, 18 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40174-015-0041-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40174-015-0041-2