Abstract

Background

The lack of a definition of urinary microbiome health convolutes diagnosis of urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially when non-traditional uropathogens or paucity of bacteria are recovered from symptomatic patients in routine standard-of-care urine tests. Here, we used shotgun metagenomic sequencing to characterize the microbial composition of asymptomatic volunteers in a set of 30 longitudinally collected urine specimens. Using permutation tests, we established a range of asymptomatic microbiota states, and use these to contextualize the microbiota of 122 urine specimens collected from patients with suspected UTIs diagnostically categorized by standard-of-care urinalysis within that range. Finally, we used a standard-of-care culture protocol to evaluate the efficiency of culture-based recovery of the urinary microbiota.

Results

The majority of genitourinary microbiota in individals suspected to have UTI overlapped with the spectrum of asymptomatic microbiota states. Longitudinal characterization of the genitourinary microbiome in urine specimens collected from asymptomatic volunteers revealed fluctuations of microbial functions and taxonomy over time. White blood cell counts from urinalysis suggested that urine specimens categorized as ‘insignificant’, ‘contaminated’, or ‘no-growth’ by conventional culture methods frequently showed signs of urinary tract inflammation, but this inflammation is not associated with genitourinary microbiota dysbiosis. Comparison of directly sequenced urine specimens with standard-of-care culturing confirmed that culture-based diagnosis biases genitourinary microbiota recovery towards the traditional uropathogens Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Conclusion

Here, we utilize shotgun metagenomic sequencing to establish a baseline of asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota states. Using this baseline we establish substantial overlap between symptomatic and asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota states. Our results establish that bacterial presence alone does not explain the onset of clinical symptoms.

Video Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are one of the most pervasive urological disorders and a substantial yearly socioeconomic burden [1, 2]. Women are at a significantly higher risk to contract UTIs than men, with 60% of all women experiencing at least one episode in their lifetime [3]. With the increase in antimicrobial resistance in microbes frequently implicated in UTI, the selection and efficacy of empiric antimicrobial therapy is a growing challenge [4]. Inconclusive or incorrect microbiological diagnosis can select for antimicrobial resistance through the initiation of inappropriate or ineffective antibiotic therapies.

Standard clinical diagnosis, comprising of microbial culture, microscopy, and automated biochemical urinalysis [5,6,7], is optimized for the detection of traditional uropathogens like uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC). In outpatient settings, approximately 80% of UTIs are attributed to UPEC, while the remaining 20% are associated with bacteria such as Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Acinetobacter species [2, 8]. UTIs are diagnosed in cases where urinary symptoms coincide with urinary inflammation and uropathogen abundance that exceeds a threshold of clinical significance (with 105 CFU/mL commonly used) [9]. Extensive resources have been allocated to the improvement of microbial diagnosis and development of consensus criteria for the initiation of antimicrobial treatment [10,11,12]. As a result, expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) has greatly improved recovery of uropathogenic bacteria [12, 13]. However, even with increased specificity, diagnostic cultures often remain negative or inconclusive and reports of clinical overtreatment of urinary disorders are frequent [14,15,16,17].

The lack of a definition of urinary microbiome health convolutes UTI diagnosis. For decades, the urinary tract has been considered sterile. Recently, culture-independent sequencing and enhanced culturing showed that even the asymptomatic urinary tract harbors diverse microbial communities [18, 19], which can be grouped into ‘urotypes’—distinct compositions of urinary microbes in individual patients [13]. Some studies implicate the urinary microbiome in urinary tract disorders, like urgency urinary incontinence [13]. Conversely, the microbiota inhabiting all sections of the genitourinary system may play a role in preventing ascension of invading uropathogen through the urinary tract into the bladder [2]. Similarly, dysbiotic shifts of the genitourinary microbiota may be associated with urinary disorders like UTIs. It has recently been proposed that urinary disorders should be considered as distinct states on a spectrum of urinary microbiome health [20]. This paradigm could help clinicians assess important clinical conditions, such as UTIs, asymptomatic bacteriuria, or urgency urinary incontinence, and evaluate the necessity of commonly prescribed antimicrobial treatments. Therefore, establishing a baseline state of urinary microbiome health has been a medical priority [13, 21,22,23,24,25,26].

Here, we use metagenomic shotgun sequencing to establish a baseline of asymptomatic genitourobiome fluctuations in healthy individuals. We use this baseline to contextualize the microbial composition of urinary specimens collected from patients presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms, clinically categorized as no growth, ‘insignificant’, ‘contaminated’, or culture-positive. We reveal that the majority of microbiota compositions characterized in specimens from patients suspected to have UTI overlaps with asymptomatic microbiota states of healthy individuals. Further, by comparing the results of standard-of-care urinalysis with sequencing results we demonstrate that taxonomic and genomic diversity of the urinary microbiota in specimens from patients suspected to have UTI is commonly underestimated by culture-based urinalysis.

Methods

Urine sample collection

Following IRB approval, remnant urine specimens, including midstream, catheterized, and urine of uncertain collection type, from de-identified patients who had urine cultures submitted as part of routine clinical care where the physician had concern for UTI were used in this study (Table 1, Table S1). Specimens were submitted to the Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis, Missouri, United States as part of routine clinical care and standard urinalysis were performed. All specimens from putative UTI patients were cultured using standard of care methods: 1 μL was plated to a MacConkey and sheep’s blood agar plates (Hardy Diagnostics) using a 1-μL calibrated loop and incubated at 35 °C in CO2 for 24 h. Suspect urine specimens were classified into one of four categories based on standard-of-care clinical procedures: (1) ‘culture-positive’, if the specimen had significant growth of one or two uropathogens (n = 48), (2) ‘contaminated’, 3 or more bacterial species growing in concentrations above threshold in standard-of-care clinical culture (105) (n = 6), (3) ‘insignificant’, < 105 colony forming unites/mL present during culturing (n = 17) and (4) ‘no growth’, specimen had no visible signs of microorganism growth during culturing (n = 51). Patient age, sex, ethnicity, and urinalysis results, including white blood cell count (cells/hpf) were collected from the medical record.

Urine samples were collected from ten asymptomatic participants enrolled through the Women’s and Infants Health Specimen Consortium (WIHSC) following an assessment of the recent medical history and current medications (see Extended Data 1). Exclusion criteria were the presence of lower urinary tract symptoms and antibiotic exposure in the 14 days prior to enrollment. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Three urine specimens were collected from each asymptomatic volunteer, on average the collections were 1.61 days apart (range 1–6 days). Sampling was approved by the Human Research Protection Office (approval number 201401115).

Sample processing and sequencing

Culture-positive specimens and specimens from asymptomatic volunteers were re-plated to MacConkey and sheep’s blood agar plates (BAP, Hardy Diagnostics) and incubated for 24h at 35 °C in 5% CO2. Species identity of isolates was determined with the VITEK MALDI-TOF MS v2.0 knowledgebase (bioMerieux). Four milliliters of all urine specimens was used to isolate metagenomic DNA. DNA extraction for all specimen types (i.e., isolates, slurries, urines) was performed using the BiOstic Bacteremia DNA Isolation Kit (Mo-Bio). DNA was sheered to a target size range of approximately 500–600 bp using the Covaris E220 sonicator with the following settings: peak incident power, 140; duty cycle, 10%, cycles per burst 200; treatment time 75 seconds; temperature 7 °C; sample volume 130 μl. Sheared DNA was purified and concentrated using MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen), eluting in 20 μl pre-warmed nuclease-free H2O. Purified sheared DNA was then end-repaired and Illumina adapters were ligated. Sample specific barcodes were annealed using T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs). Samples were purified using a MinEluted PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and size-selected to a target range of 400–900 bp on a 1.5% agarose gel. Size-selected DNA was enriched using a 18-cycle PCR reaction: a 25-μl reaction volume was prepared containing 2 μl of purified DNA, 12.5 μl 2x Phusion HF Master Mix (New England BioLabs), 1 μl of 10 MM Illumina PCR Primer Mix (5′-AAT GAT ACG GCG ACC ACC GAG ATC TAC ACT CTT TCC CTA CAC GAC GCT CTT CCG ATC T-3′ and 5′-CAA GCA GAA GAC GGC ATA CGA GAT CGG TCT CGG CAT TCC TGC TGA ACC GCT CTT CCG ATC T-3′) and 9.5 μl of nuclease-free H2O. Amplified DNA was size-selected to a target range of 500 bp on a 1.5% agarose gel and samples were pooled at 10 nM for sequencing. Sequencing libraries for a subset of 54 specimens were prepared using the Illumina Nextera XT 40 protocol. Libraries of all samples were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 500 HighOutput platform (Illumina, 2 × 150 bp).

Prior to all downstream analysis, Illumina paired-end shotgun metagenomics sequence reads were binned by barcode, quality filtered using Trimmomatic v0.3.038 (java-Xms1024m-Xmx1024m-jar trimmomatic-0.33.jar PE-phred 33 ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq3-PE-2.fa:2:30:10 LEADING:10 TRAILING:10 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20 MINLEN:60) and filtered from human DNA using DeconSeq 39 and the v38 of the human genome (default parameters) [27, 28].

Metagenome and statistical analysis

We determined the composition of the microbial communities of all specimens using MetaPhlAn2 [29]. Relative abundances extracted from MetaPhlAn2 were used in down-stream analyses. HUMAnN2 was utilized for metabolic pathway prediction [30] and pathway abundance profiles were used for analysis. Analysis were performed using the packages vegan, labdsv, ggpubr, rsample, purr, dplyr, devtools, pairwiseAdonis, and permute in R version 4.0.2. Bray-Curtis distances were calculated using the vegan package and visualized as PCoA plots via the ggplot2 package. Urotypes were identified via hierarchical clustering as previously described [13]. Briefly, between sample Bray-Curtis distance was used for hierarchical clustering using the hclust function in R (method=’average’) and urotypes were identified as cluster of highly similar composition in the resulting dendrogram. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare microbiota community metrics (richness and Shannon diversity) between all diagnostic categories and samples collected from asymptomatic volunteers. Pairwise Wilcoxon Test was used for post-hoc pairwise comparisons and P-values were corrected using the Bonferroni correction for multiple hypothesis testing. Pairwise PERMANOVA were performed using the pairwiseAdonis package in R. P values were corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using Bonferroni-correction.

A potential impact of clinical covariates on the urinary microbiota composition in symptomatic specimens was evaluated using a nested PERMANOVA design on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity values in the adonis2() function in the vegan package. The model formula took the form of: adonis2(Bray-Curtis dissimilarity~’clinical variable’, data=df, permutations=perm)

with permutations blocked in diagnostic category (setBlocks(perm)<-with(df, ‘diagnostic category)) and nperm = 999.

Taxa differentially abundant in specimens from distinct diagnostic categories were identified using LefSe [31]. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The microbial composition in clinical specimens was compared to that of the range of asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota compositions using permutation tests (1000 iterations). One of the three available samples per asymptomatic volunteer was randomly selected to generate the range of asymptomatic microbiota compositions based on Bray-Curtis distance in each interation. Deviation of the microbiota composition in clinical specimens from the asymptomatic distribution was assessed by calculating the geometric distance of each sample to the centroid of the asymptomatic distribution determined by canonical analysis of principal coordinates (CAP). To comprehensively account for the range of asymptomatic microbiota states observed in the longitudinal dataset of the asymptomatic patients (Fig. 2), 1000 permutations were performed and the average distance for each clinical sample was used for analysis.

Results

Cohort description

Remnant urine samples collected from 122 patients experiencing urinary symptoms (62% female, median age 51.5 years, 60% Caucasian) were included in this study (Table 1). Sample from both outpatient and inpatient setting were included, and specimens included both catheterized as well as midstream urine and patients from all hospital departments (Table 1). Specimens were categorized via standard-of-care clinical urine culture as: (1) ‘culture-positive’, growth of 1–2 uropathogenic species at ≥105 colony forming units (CFU)/mL (n = 48), (2) ‘contaminated’, growth of ≥ 3 bacterial species at ≥ 105 CFU/mL (n = 6), (3) ‘insignificant’, bacterial growth < 105 CFU/mL (n = 17), and (4) no growth, no bacterial or fungal growth (n = 51). As UTIs are observed more frequently in women [2, 32], we recruited ten asymptomatic female volunteers with no clinical evidence of a UTI and without antibiotic exposure in the 2 weeks preceding study enrollment as a control group. Urine samples were collected from this group at three timepoints.

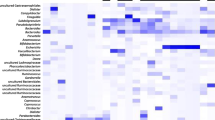

Characterization of the genitourinary microbiota

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing showed that the genitourinary microbiota composition of clinical urine samples grouped into 16 distinct clusters (‘urotypes’) frequently predominated by a single bacterial taxon (Fig. 1a, Table S2). We observed a significant association between urotypes and diagnostic categories (P < 0.001, chi-square test). The majority of ‘culture-positive’ urine specimens were predominated by Escherichia spp. (Table 2). Predominance of other known uropathogens (Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Citrobacter spp.) was less common. The genitourinary microbiota of ‘no-growth’ specimens was predominated by common inhabitants of the genitourinary tract, specifically Lactobacillus spp., Gardnerella spp., or Staphylococcus spp., as well as in rarer cases members of the Actinobacteria (Cutibacterium spp., Corynebacterium spp.), Bacteroidetes (Prevotella spp.), or Firmicutes (Ureaplasma spp.) (Fig. 1a, Table 2). Notably, urotypes 1 and 5 were defined by high abundances of either viruses (Polyomavirus) or fungi (Ascomycota, predominately Candida spp.) and were frequently identified in ‘no-growth’ specimens (Table 2). Specimens classified as ‘insignificant’ or ‘contaminated’ lacked high relative abundances of established uropathogens (Table 2).

Microbiota composition varies between categories of diagnostic urinanalysis. a Microbiota composition in 122 suspected UTI urine specimens and 10 asymptomatic control samples clustered by relative abundance (hierarchical clustering based on Bray-Curtis distance). Clinical classification of each sample is depicted below the bargraph. Clusters of similar composition (urotypes) are indicated by numbers plotted onto the dendrogram. b Constrained analysis of principal coordinates based on microbiota composition of samples of all female participants. Individual samples are colored based on clinical categorization

To contextualize the genitourinary microbiota of the clinical categories within a range of asymptomatic urotypes, we characterized the similarity between the microbial compositions identified in clinical specimens and enrollment specimens collected from asymptomatic volunteers. Importantly, all asymptomatic volunteers were female, while the sex distribution in the clinical sample collection was heterogeneous (62% female). Therefore, we first assessed similarity only between asymptomatic females and the clinical specimens collected from female participants. Dimensionality reduction via constrained analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) indicated that the majority of clinical specimens cluster within the range of microbiota compositions observed in the asymptomatic group (Fig. 1b), with a subset of predominantly ‘culture-positive’ specimens forming a distinct cluster outside the main distribution. Subsequent comparison of the genitourinary microbiota of symptomatic women and men indicated no difference of the genitourinary microbiota composition in clinical specimens between sexes (Fig. 1c). This result was supported by permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) indicating that independent of a sample’s clinical category, sex did not have a significant effect on microbiota composition of clinical specimens (P = 0.35, PERMANOVA). Similarly, race, patient type (inpatient, outpatient), and urine collection method did not explain a significant portion of the microbiota composition in specimens of symptomatic participant (P = 0.23, P = 0.76, and P = 0.41, respectively, PERMANOVA, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected), while hospital department and patient age significantly impacted the genitourinary microbiota composition in these specimens (P = 0.02, and P = 0.05, respectively, PERMANOVA, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected).

We observed no significant differences in microbial diversity between the genitourinary microbiota of asymptomatic and symptomatic women (P = 0.11, Kruskal-Wallis, Fig. S1a) or symptomatic women and men (P = 0.34, Kruskal-Wallis, Fig. S1b). Similarly, we found no significant differences in species richness between categories of female samples following P value correction (P > 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis with pairwise Wilcoxon post-hoc test, P value Bonferroni corrected, Fig. S1c) and richness did not differ between specimens collected from symptomatic men and women irrespective of clinical category (P = 0.09, Kruskal-Wallis, Fig. S1d). Functional characterization of the urinary microbiome using HUMAnN2 [30], highlighted a similar deviation of a set of ‘culture-positive’ urine specimens from the overlapping distribution of symptomatic and asymptomatic microbiome states (Fig. S2a). However, diagnostic urine category did not explain a significant amount of the variance in the functional microbiome composition for symptomatic vs asymptomatic women (P = 0.54, PERMANOVA). Moreover, the functional profile of the genitourinary microbiota did not differ between the samples of male and female symptomatic participant (P = 0.21, PERMANOVA, Fig. S2b).

Temporal stability of the asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota

To characterize the range and temporal stability of asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota states in healthy individuals, we analyzed the microbiota composition in two additional urine specimens collected at subsequent time points per asymptomatic volunteer (average distance between samplings 1.61 days (range 1–6 days)). We observed remarkable compositional and functional shifts of the genitourinary microbiome for the majority of investigated individuals (Fig. 2a–c). In 9/10 asymptomatic individuals, the dominant bacterial taxon shifted between consecutive timepoints, often to taxa not detected in preceding samples (Fig. 2a, Table S2). These shifts were frequently associated with increased abundances of bacterial taxa with known uropathogenic potential like Klebsiella (K. pneumoniae), Escherichia (E. coli), Enterococcus (E. faecalis), or Enterobacter (E. cloacae) (Fig. 2a, Table S2) and highlight the transient nature of microbial colonization of the genitourinary area.

The genitourinary microbiota composition of asymptomatic patients fluctuates. a Relative abundance of microbiota in samples collected at three consecutive time points (T1, T2, T3) from 10 asymptomatic volunteers. b Principal coordinate analysis of the microbiota composition in the three urine specimens collected from 10 symptomatic volunteers (n = 30). Points are colored by patient and subsequently collected samples are collected via lines. c Principal coordinate analysis based on functional pathway abundance determined via HUMAnN2 in the longitudinal urine specimens collected from 10 symptomatic volunteers (n = 26). Four samples did not yield sufficient functional resolution and were excluded before analysis. Points are colored by patient and subsequently collected samples are collected via lines. d Bray-Curtis distance of the microbiota composition of subsequently collected urine specimens from asymptomatic volunteers (intra-personal) compared to the distance between patients collected from different individuals at the same timepoint (inter-personal). Bray-Curtis distances between groups for each interval were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with *P < 0.05

While the microbial composition of urine specimens collected at different timepoints from the same individual was variable, characterization of the intra- and interpersonal Bray-Curtis distance revealed a detectable person-specific genitourinary microbiota signature (Fig. 2d). The Bray-Curtis distance of consecutive urine specimens from the same individual was significantly lower compared to the between-patient distance at both investigated timepoints (P = 0.03 and P = 0.003, respectively, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

Diagnostic categories reflect different states of urobiome health

To place the microbiota composition of suspected UTI urine specimens within the observed range of genitourinary microbiome health, we determined how clinical specimens deviate from the composition of the microbiota in urine samples collected from asymptomatic volunteers using permutation tests (see “Methods” section). The microbial compositions of specimens categorized as ‘insignificant’ and ‘no-growth’ predominantly fall within the 90% quantile of the asymptomatic reference group (Fig. 3a). Specimens with high relative Escherichia spp. abundances in ‘culture-positive’ specimens deviated from the distribution of asymptomatic states, while other bacteria with uropathogenic potential like Klebsiella or Proteus are better represented in the range of asymptomatic microbiota states (Fig. S3a).

The microbiota composition of diagnostic categories correspond to different states of genitourinary microbiota health. a Distance of the microbiota composition determined in urine sample classified into different diagnostic categories to the centroid of the distribution of the distribution of asymptomatic microbiota states determined by constrained analysis of principal coordinates in 100 iterations including all longitudinally collected specimens. Dotted line marks the 90% quantile of distances for specimens collected from the asymptomatic population. b Significantly enriched microbiota in suspected UTI specimens from different clinical categories. Significance of enrichment was determined via linear discriminatory analysis as implemented in LefSe with a significance threshold of P < 0.05

To identify genitourinary microbiota potentially associated with clinical symptoms in absence of genitourinary microbiome dysbiosis, we performed enrichment analysis using LefSe [31] on all samples within the 90% quantile of the asymptomatic distribution. We found no significant enrichment of bacterial taxa in ‘culture-positive’ specimens when compared to the enrollment specimens of asymptomatic volunteers (Table S3). However, bacteria with uropathogenic potential (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Escherichia coli) were overrepresented in ‘culture-positive’ specimens when compared to ‘no-growth’ samples, which were in turn enriched for Cutibacterium acnes and Ascomycota (Fig. 3b), indicating that cultivability of microorganisms in standard-of-care diagnostics is the main determinant of clinical classification between these two categories. The enrichment of anaerobic bacterial taxa (Ruminococcus torques, Bacteroides ovatus) in specimens classified as ‘insignificant’ when compared to ‘culture-positive’ samples further indicates that cultivability of organisms limits diagnostic sensitivity of conventional standard-of-care culture-based urine analysis.

To identify a potential relationship between urinary symptoms and genitourinary microbiome dysbiosis, we analyzed available white blood cell count data, commonly used as a clinical indicator of urinary tract inflammation (Fig. S3b). In the majority of suspected UTIs classified as ‘insignificant’ (8/10, 80%) and a subset of cases classified as ‘no-growth’ (14/39, 35.9%), white blood cell counts (WBC) were found to be above the clinical threshold for urinary inflammation (WBC ≥ 5 per high power field). Clinical samples with indication for urinary tract inflammation were evenly distributed between samples from within and outside the 90% quantile of the distribution of asymptomatic urinary microbiome compositions (Figs. S3b and S4), indicating that genitourinary microbiome dysbiosis alone does not explain the onset of urinary symptoms.

Diagnostic culturing can fail to reflect microbial composition of urine specimens

Culture-based recovery of the genitourinary microbiota from urine specimens represents a keystone of routine medical urine diagnostics. Therefore, we determined the ability of standard-of-care diagnostic culturing to comprehensively recover the genitourinary microbiota. We sequenced culture slurries of ‘culture-positive’ specimens and compared the recovered microbiota composition to directly sequenced urine. While microbiota compositions of culture slurries and directly sequenced urine were generally similar, a subset of samples exhibited high compositional differences between sample types (Fig. S5a). In these specimens, single bacterial taxa representing only a fraction of the microbiota composition identified by direct urinary sequencing were selectively enriched under culture conditions (Fig. S5b).

Specifically, Gardnerella spp. (undetected in 6/6 specimens) and Polyomavirus (6/6), a virus that would not be recovered in traditional culture, were systematic underrepresentated in culture-based uropathogen detection (Fig. 4). Similarly, culture-based methods failed to detect Citrobacter freundii, an emerging healthcare-associated urinary pathogen [33], in 2 of 3 cases and underestimated its abundance when detected (Fig. 4). While culture-based detection of potential uropathogens like Klebsiella (undetected in 2/13) or Escherichia (undetected in 5/28) was more reliable, these results indicate that culture-based microbial determination does not reflect the composition of diagnostic urine specimens.

Modified standard-of-care urine culture misses bacteria with uropathogenic potential. Top panel—average enrichment of distinct taxa in cultured urine (positive values) or directly sequenced urine specimens (negative values). Bottom panel—percentage of cases in which taxa were detected in metagenomic sequencing of urine specimens but went undetected in culture of urine specimens

Discussion

Following the discovery of the urinary microbiome, six characteristic genitourinary microbiota compositions have been identified in a cohort of patients with urgency urinary disorder and asymptomatic controls [13]. It has been proposed that urinary tract disorders represent states of dysbiosis on a spectrum of urinary microbiome health [20]. However, studies of the range and temporal dynamics of asymptomatic urinary microbiota states are scarce [24] and more data is needed to assess the urinary dysbiosis hypothesis. Here, we analyze the microbial composition of suspected UTI urine specimens and contextualizing them within the spectrum and fluctuations of asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota states of healthy female volunteers.

We observed that previously described genitourinary microbiota compositions [13], predominated by Lactobacillus, Gardnerella, Enterobacteriales, or Staphylococcus, can be found in a large subset of suspected UTI urine specimens. Our results further confirm that less prominent taxa, including Polyomavirus [34, 35], Ascomycota (Candida spp.) [36], and, less frequently, Cutibacterium spp., Corynebacterium spp., Prevotella spp., or Ureaplasma spp. [13, 37, 38], can dominate symptomatic urine specimens. We find that specimens classified as ‘culture-positive’ are frequently predominated by Escherichia, confirming previous results showing that, as intended [39], standard-of-care clinical urinalysis preferentially recovers organisms considered as the main etiological agents of urinary disorders [18, 40]. The spectrum of urotypes recovered from specimens classified as ‘no-growth’ or ‘insignificant’ included microorganisms impossible to recover via standard-of-care urine culturing (Polyomavirus) or not considered uropathogenic (Lactobacillus spp., Prevotella spp., Cutibacterium acnes).

To determine whether genitourinary microbiota compositions identified in suspected UTI specimens reflect different states of genitourinary microbiota dysbiosis, we analyzed the microbial composition of urine specimens collected from asymptomatic volunteers. As previously reported [13, 21,22,23,24,25,26], we observed high inter-individual differences of the urinary microbiota composition, highlighting the lack of a single ‘asymptomatic’ urobiome composition associated with asymptomatic states. Notably, urotypes identified in asymptomatic volunteers (Polyomavirus, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae) overlapped with those observed in clinical specimens collected from patients with urinary symptoms, indicating that strain differences or host factors may determine onset of clinical symptoms. Characterization of the temporal stability of urotypes revealed fluctuations in the bacterial and functional compositions of person-specific urobiomes (Fig. 2a). This observation is consistent with a recent study that combined 16S rRNA sequencing and culturing of daily urine specimens collected from asymptomatic young women to show that the genitourinary microbiota fluctuates within days between distinct community states, impacted by factors including menstruation and vaginal sex [24]. While specimens longitudinally collected from the same person were significantly more similar to one another than to samples from unrelated individuals (Fig. 2d), the stability of an individual’s genitourobiome was substantially lower than what has been reported for other body sites [41, 42]. The intrapersonal fluctuations of the genitourinary microbiota highlights the urinary tract as an area of frequently changing microbial stimuli at the interface with human immunity. Dramatic microbiome shifts are considered strong inflammatory stimuli and have been associated with disease flares in diverse body habitats [43, 44]. Consistent with recent reports [24], we observe that female asymptomatic subjects frequently shift between urotypes, potentially caused by blooms of individual taxa [45, 46]. Future studies should investigate the immunostimulatory effects of these fluctuations.

The longitudinal sampling of asymptomatic volunteers allowed us to investigate whether urinary symptoms of patients with suspected UTIs are associated with urinary dysbiosis or represent phases of heightened urinary sensitivity. ‘Culture-positive’ specimens predominated by Escherichia coli fell outside the 90% quantile of asymptomatic microbiota states. Importantly, previous studies have shown that E. coli is a relatively common member of the genitourinary microbiota and can be present at high abundance in asymptomatic women [24, 40]. Our results, however, indicate that E. coli is over-represented in symptomatic specimens compared to asymptomatic controls, consistent with its role as the dominant uropathogen [47]. The microbiota composition of all specimens categorized as ‘insignificant’, the majority of ‘no growth’, and a subset of ‘culture-positive’ urines were well-represented within the 90% quantile of asymptomatic microbiota states. This observation confirms results of prior studies, which have shown significant overlap of asymptomatic and symptomatic urobiome states of patients with urinary disorders like urgency urinary incontinence [13] or recurrent UTIs [46]. The overlap of urotypes and species between asymptomatic patients and suspected UTI cases may indicate that immune responsiveness, rather than bacterial presence alone, determines the onset of urinary symptoms. Indeed, we show variable genitourinary inflammation (white blood cell count ≥ 5) in urines categorized as ‘contaminated’, ‘insignificant’ and ‘no-growth’ (Fig. S3), for which the genitourinary microbiota compositions falls into the range of asymptomatic microbiome states. A model of UTI in which inflammatory responsiveness to bacterial colonization of the urinary tract determines the occurrence of urinary symptoms is consistent with the observation that high urine titers of potentially uropathogenic bacteria are not inevitably associated with urinary symptoms [48].

Bacterial recovery from urine specimens and resulting bacteriological thresholds are of exceptional importance for the diagnosis of urinary disorders and have been controversial [49,50,51]. One challenge with this approach is the binary nature of a specific cut-off for “positive” vs. “negative” results, understanding that like most biological pnenomenon there is a contininuum of findings and clinical correlates. Comparison of microbiota compositions of directly sequenced ‘culture-positive’ urine specimens with culture slurries indicated effective recovery of uropathogenic Escherichia, Klebsiella, and Proteus in culture-based urinalysis. However, bacteria traditionally not considered uropathogenic (Gardnerella, Lactobacillus, Polyomavirus) or less common uropathogens (Citrobacter, Enterococcus) frequently went undetected or were underrepresented in culture-based assessment (Fig. 4). Similar to previous studies [12, 18], our results highlight the limitations of standard microbial culturing for genitourinary microbiota recovery. While enhanced culturing protocols have been established to address these shortcomings, the clinical interpretive criteria for these methods are unresolved and modified versions of the standard urine culture are still widely used. Our results advocate for the general adoption of enhanced urine culture in some patient populations and highlight the need to study the role of microbes traditionally not considered uropathogenic in the pathogenesis of urinary disorders, which dominate the urinary tract in a large subset of symptomatic and ‘culture-positive’ specimens (Table S2, Fig. 4).

A limitation of our study was the availability of urine specimens collected from asymptomatic volunteers came exclusively from female volunteers and that limited clinical data are available on study subjects. Importantly, data on menstruation and vaginal sex, factors recently shown to significantly impact the genitourinary microbiota of asymptomatic women [24], were unavailable in the current study. Moreover, while we did not observe a significant impact of sex on urinary microbiota composition in suspected UTI specimens, studies have shown that key members of the female asymptomatic urinary microbiota (e.g., members of the genera Lactobacillus, Gardnerella) are absent in men [52, 53]. Therefore, it remains unanswered whether rapid species turnover observed in the urinary microbiome of asymptomatic female volunteers can similarly be observed in asymptomatic males.

Conclusions

Collectively, our data establishes overlap between symptomatic and asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota states, highlighting that immune responsiveness, rather than bacterial presence, may determine the onset of clinical symptoms and determine genitourinary microbiome health. Prior work at the interface of bladder immunity and bacterial pathogenesis has indicated individualized sensitivities to recurrence of infectious episodes, which could explain how the same bacterial composition can result in different symptomatic outcomes [54]. Characterization of the mechanism that govern individualized sensitivities for developing urinary symptoms promises to move clinical diagnostics of urinary disorders beyond the determination of bacterial presence, guide intervention strategies and establish a more comprehensive picture of what constitutes urinary microbiome health.

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data supporting these studies conclusions has been uploaded to NCBI SRA under the BioProject accession number PRJNA700071. All other supporting information is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- BAP:

-

Blood agar plates

- CAP:

-

Constrained analysis of principal coordinates

- CFU:

-

Colony forming units

- EQUC:

-

Expanded quantitative urine culture

- UPEC:

-

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infections

- PERMANOVA:

-

Permutational analysis of variance

- WBC:

-

White blood cell counts

- WIHSC:

-

Women’s and Infants Health Specimen Consortium

References

Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Milsom I. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United States: a systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(2):130–40.

Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:269–84.

Foxman B. Urinary tract infection syndromes. Occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2014;28(1):1–13.

Chen Y-H, Ko W-C, Hsueh P-R. Emerging resistance problems and future perspectives in pharmacotherapy for complicated urinary tract infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:587–96.

Schmiemann G, Kniehl E, Gebhardt K, Matejczyk MM, Hummers-Pradier E. The Diagnosis of Urinary Tract Infection. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:361–7.

Bailey AL, Burnham CAD. Reducing the time between inoculation and first-read of urine cultures using total lab automation significantly reduces turn-around-time of positive culture results with minimal loss of first-read sensitivity. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:1135–41.

Kayalp D, Dogan K, Ceylan G, Senes M, Yucel D. Can routine automated urinalysis reduce culture requests? Clin Biochem. 2013;46:1285–9.

Bailey AL, Burnham C-AD. Reducing the time between inoculation and first-read of urine cultures using total lab automation significantly reduces turn-around-time of positive culture results with minimal loss of first-read sensitivity. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(6):1135–41.

Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Johnson JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:745–58.

Loeb M, Bentley DW, Bradley S, Crossley K, Garibaldi R, Gantz N, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term–care facilities: results of a consensus conference. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:120–4.

Zhang X, Rowan N, Pflugeisen BM, Alajbegovic S. Urine culture guided antibiotic interventions: a pharmacist driven antimicrobial stewardship effort in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:594–8.

Price TK, Dune T, Hilt EE, Thomas-White KJ, Kliethermes S, Brincat C, et al. The clinical urine culture: enhanced techniques improve detection of clinically relevant microorganisms downloaded from. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1216–22.

Pearce MM, Hilt EE, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Thomas-White K, Fok C, et al. The female urinary microbiome: a comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. MBio. 2014;5:e01283–14.

Lin E, Bhusal Y, Horwitz D, Shelburne SA, Trautner BW. Overtreatment of enterococcal bacteriuria. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:33–8.

Silver SA, Baillie L, Simor AE. Positive urine cultures: a major cause of inappropriate antimicrobial use in hospitals? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2009;20:107–11.

Cope M, Cevallos ME, Cadle RM, Darouiche RO, Musher DM, Trautner BW. Inappropriate treatment of catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria in a tertiary care hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1182–8.

Eyer MM, Läng M, Aujesky D, Marschall J. Overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria: a qualitative study. J Hosp Infect. 2016;93:297–303.

Hilt EE, McKinley K, Pearce MM, Rosenfeld AB, Zilliox MJ, Mueller ER, et al. Urine is not sterile: Use of enhanced urine culture techniques to detect resident bacterial flora in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:871–6.

Wolfe AJ, Toh E, Shibata N, Rong R, Kenton K, FitzGerald MP, et al. Evidence of uncultivated bacteria in the adult female bladder. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1376–83.

Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L. Female urinary microbiota. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:282–6.

Thomas-White KJ, Hilt EE, Fok C, Pearce MM, Mueller ER, Kliethermes S, et al. Incontinence medication response relates to the female urinary microbiota. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;27:723–33.

Thomas-White K, Forster SC, Kumar N, Van KM, Putonti C, Stares MD, et al. Culturing of female bladder bacteria reveals an interconnected urogenital microbiota. Nat Commun. 2018;2018(9):1–7.

Price TK, Lin H, Gao X, Thomas-White KJ, Hilt EE, Mueller ER, et al. Bladder bacterial diversity differs in continent and incontinent women: a cross-sectional study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:729.e1–729.e10.

Price TK, Wolff B, Halverson T, Limeira R, Brubaker L, Dong Q, et al. Temporal dynamics of the adult female lower urinary tract microbiota. MBio. 2020;11:e00475–20.

Price T, Hilt E, Thomas-White K, Mueller E, Wolfe A, Brubaker L. The urobiome of continent adult women: a cross-sectional study. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;127:193–201.

Adebayo AS, Ackermann G, Bowyer RCE, Wells PM, Humphreys G, Knight R, et al. The urinary tract microbiome in older women exhibits host genetic and environmental influences. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:298–305.e3.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20.

Schmieder R, Edwards R. Fast identification and removal of sequence contamination from genomic and metagenomic datasets. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17288 Rodriguez-Valera F, editor.

Truong DT, Franzosa EA, Tickle TL, Scholz M, Weingart G, Pasolli E, et al. MetaPhlAn2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat Methods. 2015;12(10):902–3.

Franzosa EA, McIver LJ, Rahnavard G, Thompson LR, Schirmer M, Weingart G, et al. Species-level functional profiling of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes. Nat Methods. 2018;15:962–8.

Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:1–18.

Pujades-Rodriguez M, West RM, Wilcox MH, Sandoe J. Lower urinary tract infections: management, outcomes and risk factors for antibiotic re-prescription in primary care. EClinicalMedicine. 2019;14:23–31.

Ranjan KP, Ranjan N. Citrobacter: an emerging health care associated urinary pathogen. Urol Ann. 2013;5(4):313–4.

Garretto A, Thomas-White K, Wolfe AJ, Putonti C. Detecting viral genomes in the female urinary microbiome. J Gen Virol. 2018;99:1141–6.

Santiago-Rodriguez TM, Ly M, Bonilla N, Pride DT. The human urine virome in association with urinary tract infections. Front Microbiol. 2015;0:14.

Ackerman AL, Underhill DM. The mycobiome of the human urinary tract: potential roles for fungi in urology. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:5–5.

Baka S, Kouskouni E, Antonopoulou S, Sioutis D, Papakonstantinou M, Hassiakos D, et al. Prevalence of ureaplasma urealyticum and mycoplasma hominis in women with chronic urinary symptoms. Urology. 2009;74:62–6.

Burnham P, Dadhania D, Heyang M, Chen F, Westblade LF, Suthanthiran M, et al. Urinary cell-free DNA is a versatile analyte for monitoring infections of the urinary tract. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–10.

Kass EH. Asymptomatic infections of the urinary tract. Trans Assoc Am Phys. 1956;69:56–64.

Price TK, Dune T, Hilt EE, Thomas-White KJ, Kliethermes S, Brincat C, et al. The clinical urine culture: enhanced techniques improve detection of clinically relevant microorganisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54:1216–22.

Oh J, Byrd AL, Park M, Kong HH, Segre JA. Temporal stability of the human skin microbiome. Cell. 2016;165:854–66.

Mehta RS, Abu-Ali GS, Drew DA, Lloyd-Price J, Subramanian A, Lochhead P, et al. Stability of the human faecal microbiome in a cohort of adult men. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:347–55.

Kong HH, Oh J, Deming C, Conlan S, Grice EA, Beatson MA, et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012;22:850–9.

Belkaid Y, Naik S. Compartmentalized and systemic control of tissue immunity by commensals. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(7):646–53.

Mores CR, Price TK, Wolff B, Halverson T, Limeira R, Brubaker L, et al. Genomic relatedness and clinical significance of Streptococcus mitis strains isolated from the urogenital tract of sexual partners. Microb Genom. 2021;7(3):000535.

Thänert R, Reske KA, Hink T, Wallace MA, Wang B, Schwartz DJ, et al. Comparative genomics of antibiotic-resistant uropathogens implicates three routes for recurrence of urinary tract infections. MBio. 2019;10:e01977–19.

Klein RD, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: microbial pathogenesis, host–pathogen interactions and new treatment strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18(4):211–26.

Nicolle LE. The paradigm shift to non-treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Pathogens. 2016;5(2):38.

Roberts KB, Wald ER. The diagnosis of UTI: colony count criteria revisited. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20173239.

Primack W, Bukowski T, Sutherland R, Gravens-Mueller L, Carpenter M. What urinary colony count indicates a urinary tract infection in children? J Pediatr. 2017;191:259–261.e1.

Kwon JH, Fausone MK, Du H, Robicsek A, Peterson LR. Impact of laboratory-reported urine culture colony counts on the diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infection for hospitalized patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137:778–84.

Pohl HG, Groah SL, Pérez-Losada MP-L, Ljungberg I, Sprague BM, Caldovic L, et al. The urine microbiome of healthy men and women differs by urine collection method. Int Neurourol J. 2020;24:41–51.

Bajic P, Van Kuiken ME, Burge BK, Kirshenbaum EJ, Joyce CJ, Wolfe AJ, et al. Male bladder microbiome relates to lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6:376–82.

Wu J, Hayes BW, Phoenix C, Macias GS, Miao Y, Choi HW, et al. A highly polarized TH2 bladder response to infection promotes epithelial repair at the expense of preventing new infections. Nat Immunol Nat Res. 2020;21:671–83.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jessica Hoisington-Lopez, MariaLynn Crosby, Brian Koebbe, and Eric Martin, of The Edison Family Center for Genome Sciences & Systems Biology, for assistance with high-throughput sequencing and computing. We would like to thank members of the Dantas lab for helpful comments on the manuscript and analyses.

Funding

This work was supported in part by awards to G.D. and C.A.B. from The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital ICTS Pilot Award (8037-88), and to G.D. from the NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DP2DK098089) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM099538). B.A.-O. was supported by a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship (DGE-1143945). R.T. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the German Research Foundation (402733540). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.A.-O., R.T., C.-A.D.B., and G.D. conceived the study design, experiments and analysis. B.A.-O., C.-A.D.B., and G.D. assembled the cohorts. B.A.-O., M.A.W., and C.-A.D.B. oversaw the collection of samples and clinical metadata. B.A.-O. extracted metagenomic DNA and prepared sequencing libraries. B.A.-O. and R.T. analyzed clinical metadata and shotgun metagenomic sequencing data. R.T. and B.A.-O. drafted the manuscript and figures with input from C.-A.D.B. and G.D. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Sampling was approved by the Human Research Protection Office (#201401115).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Community metrics of urine specimens from distinct diagnostic categories and asymptomatic volunteers do not differ. a) and b), Shannon diversity of a) all female participant grouped by diagnostic categories and b) all symptomatic participants of both sexes. c) and d), microbiota richness of c) all female participant grouped by diagnostic categories and d) all symptomatic participants of both sexes. Individual samples are colored based on clinical categorization.

Additional file 3: Figure S2.

Functional profile of the genitourinary microbiota. Principal coordinate analysis based on functional pathway abundance determined via HUMAnN2 for a) all female participants and b) all symptomatic participants of both sexes. Individual samples are colored based on clinical categorization.

Additional file 4: Figure S3.

Samples outside the range of asymptomatic microbiome states are dominate by E. coli but not associated with increased inflammation. B) Scatterplot of the relative abundance of the most abundant intestinal microbiota from ‘culture-positive’ specimens plotted against each specimen’s average distance from the centroid of the asymptomatic distribution of microbiota states as depicted in Fig. 3a. Sample density at each distance is plotted on top of the graph. b) White blood cell count (cells/high power field - hpf) determined via microscopic examination in urine specimens classified into different diagnostic categories. Specimens are labeled based on whether the determined microbiota compositions fell within (dark bar) or outside (light bar) the 90% quantile of asymptomatic microbiota compositions as depicted in Fig. 3a.

Additional file 5: Figure S4

. White blood cell count is independent of microbiota composition in the subset of investigate urine specimens. Microbiota composition of urine specimens (stacked bargraph) is grouped by clinical diagnostic category. Specimens are further grouped based on whether the determined microbiota compositions fell within (dark top bar) or outside (light top bar) the 90% quantile of asymptomatic microbiota compositions. Corresponding white blood cell counts determined via high power field microscopy are depicted in tiles under each bar.

Additional file 6: Figure S5

. Microbiota states of individual specimens is not represented by standard-of-care urine culture. a) Bray Curtis similarity (1-Bray Curtis distance) of directly sequenced and cultured urine specimens. b) Stacked barchart depicting the microbiota composition of directly sequenced (left bar) and cultured (right bar) ‘culture-positive’ urine specimens. Pairwise Bray Curtis similarity is indicated in tiles below each sample pair.

Additional file 7: Table S1.

Cohort metadata.

Additional file 8: Table S2.

Taxonomic composition of urine metagenomes as determined via Metaphlan2

Additional file 9: Table S3.

LefSe enrichment results

Additional file 10.

Extended Data 1 Case report form asymptomatic participants

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adu-Oppong, B., Thänert, R., Wallace, M.A. et al. Substantial overlap between symptomatic and asymptomatic genitourinary microbiota states. Microbiome 10, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01204-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01204-9