Abstract

Background

Marine holobionts depend on microbial members for health and nutrient cycling. This is particularly evident in cnidarian-algae symbioses that facilitate energy and nutrient acquisition. However, this partnership is highly sensitive to environmental change—including eutrophication—that causes dysbiosis and contributes to global coral reef decline. Yet, some holobionts exhibit resistance to dysbiosis in eutrophic environments, including the obligate photosymbiotic scyphomedusa Cassiopea xamachana.

Methods

Our aim was to assess the mechanisms in C. xamachana that stabilize symbiotic relationships. We combined labelled bicarbonate (13C) and nitrate (15N) with metabarcoding approaches to evaluate nutrient cycling and microbial community composition in symbiotic and aposymbiotic medusae.

Results

C-fixation and cycling by algal Symbiodiniaceae was essential for C. xamachana as even at high heterotrophic feeding rates aposymbiotic medusae continuously lost weight. Heterotrophically acquired C and N were readily shared among host and algae. This was in sharp contrast to nitrate assimilation by Symbiodiniaceae, which appeared to be strongly restricted. Instead, the bacterial microbiome seemed to play a major role in the holobiont’s DIN assimilation as uptake rates showed a significant positive relationship with phylogenetic diversity of medusa-associated bacteria. This is corroborated by inferred functional capacity that links the dominant bacterial taxa (~90 %) to nitrogen cycling. Observed bacterial community structure differed between apo- and symbiotic C. xamachana putatively highlighting enrichment of ammonium oxidizers and nitrite reducers and depletion of nitrogen-fixers in symbiotic medusae.

Conclusion

Host, algal symbionts, and bacterial associates contribute to regulated nutrient assimilation and cycling in C. xamachana. We found that the bacterial microbiome of symbiotic medusae was seemingly structured to increase DIN removal and enforce algal N-limitation—a mechanism that would help to stabilize the host-algae relationship even under eutrophic conditions.

Video abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multicellular life depends on microorganisms for tight symbiosis, for their ability to drive biogeochemical processes, thus providing nutrients, or both [1]. Hosts and their associated microbial communities, together referred to as holobionts, have received increasing attention, especially in the context of ongoing global declines in coral reefs [2]. Cnidarian holobionts include bacteria, archaea, fungi, and viruses. Some form additional photosymbioses with endosymbiotic unicellular dinoflagellates from the family Symbiodiniaceae [3, 4]. The associated microorganisms, in particular bacteria and Symbiodiniaceae, are tightly linked to holobiont nutrient cycling and health [5].

The inclusion of algae allows the holobiont to directly access autotrophically fixed carbon (C) and thereby thrive in nutrient limited environments where heterotrophic food supply is strongly limited [6]. Photosynthetically fixed C is translocated mostly in the form of glucose from algae to host [7], but also other metabolites are exchanged [8]. In some cnidarian species (e.g. Cassiopea spp.), phototrophic C fixation can completely cover the host’s energetic requirements [9]. In turn, the host provides protection and favourable conditions in respect to light and CO2 [10]. This symbiosis is the foundation of coral reefs, which provide on a global level ecosystem services with an estimated value of US$375 billion per year [11].

The cnidarian-symbiodinian relationship includes facultative associations, for instance Exaiptasia and the stony coral Astrangia poculata and obligate association in most tropical reef-building corals. This symbiosis is remarkably sensitive to environmental changes and environmental stressors can cause its breakdown resulting in coral bleaching [12]. Such loss of photosynthetic pigments can be accompanied by the dysbiosis of other microbial associates [2, 13]. Obligate hosts may sometimes survive bleaching periods and recover [14], but nonetheless, climate change driven temperature rises and resulting mass bleaching have critical consequences for coral reefs on a global scale [15]. Consequently, key questions for conservation are what prevents host-algae dissociations and which factors support the reestablishment of disrupted symbiotic relationships once bleaching occurs.

Besides temperature, high nutrient levels can either directly cause bleaching or lead to dysbiosis, disease and host mortality [16]. Naturally, nitrogen (N) is limited in oligotrophic tropical coral reefs. It can be acquired by heterotrophic feeding of the host and passed on to its associates, e.g. as ammonium or amino acids, and further efficiently recycled within the holobiont [17]. N can also be directly obtained from seawater, where it is commonly present at low concentrations in the form of dissolved inorganic N (DIN, i.e. nitrate (NO3-), nitrite (NO2−) and ammonium (NH4+)), dissolved organic N, or particulate organic N [8]. Cnidarian hosts are able to incorporate ammonium but often associated microbial communities (particularly Symbiodiniaceae) account for most DIN uptake [17]. Symbiodiniaceae assimilate ammonium and nitrate, many microbial associates are involved in acquiring and efficiently (re)cycling N, and prokaryote diazotrophs can even fix atmospheric nitrogen [17,18,19]. The host benefits from a limited N availability [8, 20] as excess inorganic N can disrupt the host-symbiont partnership by altering the N:P (phosphorus) ratio within the holobiont and exacerbate heat-induced bleaching [17, 21]. Recently, prokaryote associates have also been linked to Symbiodiniaceae N limitation in coral holobionts by metabolizing and therefore limiting biologically available N [18, 22].

Cnidarian-symbiodinian holobionts are diverse and some are adapted to different trophic environments than coral reefs. Consequently, they vary in their heterotrophic feeding capacity and likely in their ability to assimilate and retain N [6, 23, 24]. A higher heterotrophic feeding capacity seems to correlate with an increased bleaching resistance in corals [23]. The mechanisms regulating nutrient acquisition and N cycling within the holobiont are still poorly resolved, but are key for understanding the intricate Cnidaria-Symbiodiniaceae symbiosis [17, 22, 25].

Of particular interest are organisms adapted to high nutrient environments as they might provide insights on how to effectively mitigate negative consequences of eutrophication. A potential mechanism of mitigation is the capacity of hosts to restrict N access from their symbionts. Examples of highly adapted organisms are obligate photosymbiotic jellyfishes of the genus Cassiopea, which persist in mangrove environments and seagrass beds with high nutrient loads as well as in more oligotrophic reef flats [9, 26, 27]. C. xamachana has recently gained increased attention as a suitable organism to study the cnidarian-symbiodinian relationship [28,29,30]. In contrast to most corals, its algal symbiosis can be discontinued for extended periods (>8 weeks), and re-infection with a range of Symbiodiniaceae species is easily possible [30, 31].

Consequently, C. xamachana provides a number of physiological characteristics turning it into a suitable model organism to study nutrient dynamics in Cnidaria and their resistance to nutrient-facilitated or induced bleaching. However, up to now comparatively little is known about its energy and nutrient budgets. Similar to other photosymbiotic scyphomedusae such as Linuche unguiculata [32], C. xamachana seems to attain the majority of its C requirements from photosynthesis, as bleached or light limited C. xamachana fail to maintain their mass even in the presence of high heterotrophic food concentrations [33, 34]. Further, adult medusae can utilize different DIN species including ammonium and nitrate [35] that are transferred between host and symbiont [36]. However, quantitative data on C and N acquisition is missing and it remains unknown in which form and at which rates elements are cycled among members of the holobiont in C. xamachana.

In this study our aim was to assess energy and nutrient cycling in C. xamachana to identify mechanisms stabilizing host-Symbiodiniaceae relationships in eutrophic environments. A key objective was to consider the microbiome due to its probable functional importance. Consequently, we combined pulse-chase experiments to trace isotopic labels with host physiological responses and gene amplicon sequencing of the bacterial microbiome. This allowed us to compare energy cycling in symbiotic and aposymbiotic individuals and relate nutrient uptake and turnover (or assimilation) rates with biodiversity and composition of the bacterial microbiome in C. xamachana.

Material and methods

Study organism and preparation of experiments

Cassiopea xamachana specimens employed in this study belong to strain T1A (draft genome available [37]). All individuals were from the same cohort, monoclonal, and propagated asexually as polyps. Associated Symbiodiniaceae were identified as clade A (the representative sequence matched A3 closely) by ITS2 sequencing (tested on 8 representative individuals, primers ‘ITS2symbF’: 5′ TGTGAATTGCAGAACTCCGT 3′ and 'ITS2symbR': 5′ TTTCCAAAGTCCTTTTCATCTTTC 3’ covering the full ITS2 and partial 5.8S and 28S genes, length: ~667 bp) and a subsequent blastn search (query cover: 100 %, Identity: 99 %). Adult medusae were maintained in a 500 L aquarium equipped with a filtration system, protein skimmer and reef sand. Two LED lights (Prime 16HD Reef, AquaIllumination) were set to a 12:12 h light to dark cycle at 100–150 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The medusae were kept in artificial seawater (ASW) with 35 PSS-78 salinity at 27–29°C temperature and fed ad libitum with freshly hatched or frozen Artemia salina 3–5 times a week.

For the experimental preparation, 35 adult symbiotic medusae (49 ± 7 mm bell diameter) were randomly selected and transferred to a separate tank (~15 L) containing filtered ASW (0.22 μm, changed daily) and air stones. Specimens were acclimated for 4 days. Aposymbiotic medusae were prepared by menthol-bleaching following a protocol modified from Matthews et al. [38]. Briefly, additional 20 individuals were incubated in ASW spiked with 0.38 mM menthol (from 1.28 M stock solution of 99 % menthol (Sigma-Aldrich) in 95 % ethanol) 8 h per day for 4 days. Incubation chambers were placed in a plant incubator (MLR-352, Panasonic) at 28°C and ~350 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Medusae were considered fully bleached when no fluorescence was detectable (Imaging-PAM, Waltz, Germany) and Symbiodiniaceae cells were not detected under a light microscope (Olympus Optical, mod. CHK at 400×). All 20 fully bleached medusae were kept in a separate, Symbiodiniaceae-free (0.22 μm ASW) system for 21 days at the same temperature and light regime as in the rearing tank.

Experimental procedure—pulse-chase labelling experiment

In order to assess inorganic N and C assimilation, we performed a pulse-chase isotope labelling experiment with three treatments. Treatments included symbiotic individuals incubated under light conditions (SymL), symbiotic individuals incubated in darkness (SymD), and aposymbiotic individuals incubated in light (ApoL) (Fig. 1). Prior to the experiment, five symbiotic and five aposymbiotic specimens were sampled to establish natural stable isotope ratios (T0; Fig. 1). The remaining specimens (30 symbiotic and 15 aposymbiotic) were randomly assigned to one of the three treatments. The experiment consisted of an incubation with tracers (pulse), followed by a tracer-free incubation (chase). All incubations were performed in glass jars (‘incubation chamber’; IKEA Korken, ~1L) in incubators (MLR-352, Panasonic) at 28°C. Light was adjusted to 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1.

Experimental set-up. Boxes depict treatments (colour) and number of specimens (n). Treatments include symbiotic-light (SymL, orange), symbiotic-dark (SymD, grey), and aposymbiotic-light (ApoL, pink). Each vertical line represents a sampling event (T0, T1, T2, and T3) for 5 specimens from each treatment

At the start of the experiment, each medusae was transferred to an incubation chamber filled with 13C and 15N enriched seawater (Sigma-Aldrich; 117 μM NaH13CO3, 98 atom % 13C; 1.18 mM Na15NO3, 98 atom % 15N). Dissolved oxygen (DO) was measured for each chamber (YSI® ProODO™ optical DO sensor, Yellow Springs, USA), then chambers were closed airtight without any remaining bubbles and randomly arranged in the incubators. After ~5 h, chambers were opened one by one and DO measured (Fig. 1). Each medusa was rinsed with filtered ASW and five specimens from each treatment (SymL, SymD, and ApoL; n = 15) were sampled (T1). Sampled individuals were measured (bell diameter using standard callipers), rinsed with abundant MilliQ water, wrapped in sterile aluminium foil, frozen at −80°C for about 30 min, and stored at −20°C until further processing. Meanwhile, the incubation chambers were carefully cleaned (bleach and MilliQ) and filled with filtered (tracer-free) ASW. The remaining medusae (n = 30) were transferred back into the chambers for the chase part of the experiment. Chambers were closed and handled as described above. After ~3 h, five individuals from each treatment (n = 15) were sampled (T2, ‘chase3h’), and the remaining individuals (n = 15) were sampled after another 3 h (T3, ‘chase6h’).

Wet weight and bell diameter

During the experiment, only bell diameter (BD) was measured to minimize handling stress. In order to establish BD to wet weight (WW) relationships, we measured both in additional 35 symbiotic and 12 aposymbiotic individuals. We examined changes in mass and size of the 12 aposymbiotic medusae by BD and WW measurements 2, 8, and 25 days after the end of the menthol treatment (Additional File 1: Fig.S1). Measurements after 25 days were used to establish the BD-WW relationships for aposymbiotic individuals (the isotopic pulse-chase experiment was implemented 21 days after bleaching).

To measure WW, medusae were individually captured with a fine plastic net, gently shaken to remove excess water and weighted in a cup containing ASW. Immediately after weighing, maximum bell diameter (BD) was measured using standard callipers. WW-BD relationships were established using linear regressions and the best model was selected based on Akaike information criterion (AIC), resulting in a second-degree polynomial function for the symbiotic and a linear function for the aposymbiotic medusae (Additional File 1: Fig.S2).

Productivity

DO concentrations before and after each incubation were used to calculate respiration (R; for dark incubation and for aposymbiotic medusae) and net primary production (Pn; for light incubation of symbiotic specimens) rates as

where Vchamber and Vmedusa stand for incubation chamber volume and medusa volume, respectively. Vmedusa was calculated from WW based on the seawater density at 35 PSS-78, 28°C and standard atmospheric pressure. For symbiotic medusae, gross primary production (Pg; Pg = Pn+ R) and the Pg:R ratio were calculated for the 5 h light pulse period. Of note, these values are approximations as there are systematic differences between light and dark respiration and both can vary over time [39].

Heterotrophic nutrient dynamics

To assess the relative importance of heterotrophic feeding in C. xamachana, symbiotic specimens were fed with live zooplankton enriched with 13C and 15N. Zooplankton was enriched by first culturing Isochrysis galbana (haptophyte alga) for four days in a modified F/2 medium enriched with 750 mg L−1 NaH13CO3 (98 % heavy isotope) and 75 mg L−1 Na15NO3 (98 % heavy isotope, accounting for all nitrate present in the medium) to enrichment levels of ~10 AP13C (atom percent, see below) and ~15 AP15N. Isotopically enriched algae were fed to Artemia salina for 24–48 h. Four C. xamachana medusae (~3 cm BD) were starved for three days under normal light conditions, then fed ad libitum with labelled A. salina and sampled after ~5–6 h to allow for complete digestion (based on visual inspection of the gastric cavity). Each individual was thoroughly rinsed with ASW and MilliQ, and the gastric cavity excised with a clean scalpel to exclude partially undigested food particles. Medusae were then preserved as described above for stable isotope analyses (SIA).

Sample processing

All frozen C. xamachana samples were homogenized. Aliquots were taken from all treatments for microbial analyses after isotopic labelling (pulse; n = 15). The tissue homogenate of each sample was separated by centrifugation into host and algal symbiont fractions. Algal cell counts were conducted using a haemocytometer under a light microscope. Algal and host fractions were freeze-dried before SIA. For detailed sample processing see Additional File 2: Text S1.

Stable isotope analysis (SIA)

SIA was performed via combustion in a Eurovector EA3028 elemental analyser coupled to a Nu Instruments Perspective-series stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer in continuous flow mode. SIA results were firstly expressed in δ15N and δ13C, based on the isotopic composition of atmospheric N2 and on the Pee Dee Belemnite (PDB) standard, respectively. Acetanilide standards measurements were used to calculate the machine precision as percent relative standard deviation (standard deviation/mean × 100). Measurement precision in the pulse-chase experiment was 1.4 % for δ13C and 4.1 % for δ15N, while it was 0.2 % for δ13C and 12.8 % for δ15N for the heterotrophic experiment. For the pulse-chase experiment, each fraction (host and algae) from each medusa was measured in duplicates. The mean of both measurements was used for statistical analysis. Due to low sample mass for the algal symbiont fraction, only one reading was obtained in three samples (SymD-pulse, SymD-chase6h and SymL-chase6h). Isotope abundances were then converted to atom percent of 13C (AP13C) and 15N (AP15N) following Fry [40] after

where H and L refer to the number of light and heavy isotope atoms of the element E (i.e. C or N). Enrichment of both fractions in the heterotrophic experiment was calculated as atom percent excess (APE = APsample − APcontrols). Then the enrichment of the symbiont was converted to percentage of enrichment relative to the host’s enrichment ((APEAlgal / APEHost) × 100). When necessary, a certified acetanilide standard was spiked in samples from the heterotrophic experiment to increase sample mass and/or to dilute highly enriched samples. APE values were then derived from mass balance equations.

SIA data analysis

Data analysis was preformed after normality and homogeneity of variance were confirmed. Enrichment was tested with pairwise Welch two-sample upper-tailed t-tests applying Holm corrections for multiple comparisons. Effects of treatment, incubation and fraction were tested using linear mixed effect models or, when failing statistical requirements, with Kruskal-Wallis test by rank followed by post-hoc Wilcoxon rank sum exact test with Holm correction. The same non-parametric approach was used to test for difference in productivity (Pn) and respiration (R) among treatments. All tests were performed in R version 4.0.2 [41].

Bacterial community analysis

DNA from five medusae per treatment was extracted from homogenized tissue using a modified 2x CTAB chloroform protocol after Coffroth et al. [42]. DNA was quantified on a Multiskan GO (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). The primers 784F (5′-TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGAGGATTAGATACCCTGGTA-3′) and 1061R (5′-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCRRCACGAGCTGACGAC-3′) [43] with Illumina over-hang adaptor sequences (underlined above) were used to amplify the variable regions 5 and 6 of the 16S rRNA gene. For amplification and sequencing details see Additional File 2: Text S2.

Sequencing results were processed in Qiime2 [44]. Forward and reverse reads were split according to barcodes and assembled to contigs. Contigs >310 bp and those containing ambiguous bases were discarded. Sequences were quality filtered and categorized in amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using DADA2 [45]. The resulting 303 ASVs were aligned against SILVA [46], release 138.1, using a primer-specific classifier trained in Qiime2. If present, chloroplasts, mitochondria, Archaea, eukaryotes and at the phylum level unknown sequences were removed. In total, we produced 16 16S rRNA gene libraries containing 221,216 sequences (252,674 before quality control) from one extraction control, five SymL, five SymD, and five ApoL C. xamachana samples. ASVs with an occurrence of ≥10 % in the extraction control compared to all samples were removed (i.e. 7 ASVs removed, 6 occurred only in the control; Additional File 3: Table S2) to account for potential contamination. Then stacked column plots depicting bacterial community compositions at the family level were constructed, and alpha diversity indices (ASV richness, Simpson and Shannon diversity) were calculated after implementation of a combined rarefaction-extrapolation procedure [47]. Evenness was computed from unrarefied data and phylogenetic diversity was established after Faith [48]. Alpha diversity indices were selected to provide largely independent measures (richness, evenness, and Faith) and comparability with other studies (Shannon and Simpson). Indices were compared among treatments using ANOVA analyses, or Kruskal-Wallis tests if assumptions of heteroscedasticity could not be met after data transformations. We used relative ASV densities (i.e. contribution of ASVs to total no. of reads per sample) computed from unrarefied data to establish a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix and visualized sample similarity in a non-metric dimension scaling (NMDS) biplot using vegan [49]. Differences between samples and treatments were assessed using PERMANOVAs (Holm correction applied for multiple pairwise comparisons). Further, we assessed differences in within-treatment variability in community similarity, by pooling all pairwise Bray-Curtis similarity scores for within-treatment comparisons of samples and assessing differences among treatments using a Kruskal-Wallis test. All statistical tests have been performed in R and plots were constructed using ggplot2 [50]. The script can be found in Additional File 4.

Differences in predicted functional profiles based on phylogenetic inference of the associated bacterial communities were assessed using METAGENassist [51]. We used the cleaned ASV table (Additional File 3: Table S2) to perform ‘taxonomic-to-phenotypic mapping’ in METAGENassist, where all ASVs were taxonomically assigned and mapped, condensed into 184 functional taxa, and filtered based on interquartile range [52]. The remaining 175 functional taxa were normalized across samples by sum and over taxa by autoscaling. We analysed the dataset for ‘metabolism by phenotype’ using the Euclidean distance measure and clustered the 15 most differentially abundant metabolic processes (selected with random forest) using single algorithm.

Results

Bleaching and productivity

Menthol bleaching successfully produced aposymbiotic C. xamachana medusae after ~10 incubation days (Additional File 1: Fig.S1). However, even with regular feeding (≥ thrice a week ad libitum) aposymbiotic medusae shrank from 2.54 ± 0.47 to 1.35 ± 0.24 g over 29 days and survived for little over ten weeks. Symbiotic and aposymbiotic medusae differed in their WW to BD relationship (Additional File 1: Fig.S1, S2). Respiration (R) in aposymbiotic (49 ± 8 μg O2 g−1 h−1, measured under light conditions) was higher (pHolm < 0.001) than in symbiotic (28 ± 14 μg O2 g−1 h−1, measured under dark conditions) medusae. Gross primary production (Pg) for symbiotic specimens was 56 ± 15 μg O2 g−1 h−1 and the Pg:R ratio for the 5 h pulse period was 2.0 ± 0.7.

Inorganic carbon and nitrogen

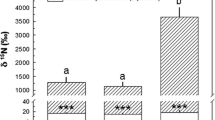

All fractions in all treatments were significantly enriched in 13C and 15N after the pulse, chase3h and chase6h (for all pHolm < 0.01) compared to the controls (Fig. 2a, b; Additional File 3: Table S3, S4). As anticipated, the algal fraction of the SymL treatment yielded the highest AP13C enrichment (2.57–3.35), followed by the respective host fraction (1.48–2.23). Owing to the lack of photosynthetic activity, both SymD and ApoL showed a much smaller overall enrichment (1.09–1.13). Further, we found that Symbiodiniaceae densities were an important factor explaining variation in 13C enrichment of the SymL host fraction (r2Adj = 0.68, slope = 0.17, plm < 0.001, Fig. 2c). We also found a good accordance between host AP13C and net primary production (Pn) computed from O2 measurements (r2Adj = 0.74, slope = 10.84, plm < 0.001, Additional File 1: Fig.S3). Surprisingly, the highest 13C enrichment for both the host and algal fraction of SymL occurred at chase rather than at pulse (AP13CChase3h > AP13CPulse and AP13CChase3h > AP13CChase6h, pLME < 0.01). A similar delay in tissue enrichment was also found in the algal fraction of SymD, with the greatest enrichment at chase6h (pWilcox < 0.05). Conversely, SymD host fraction peaked at pulse and showed lowest enrichment levels at chase6h.

Nutrient dynamics in C. xamachana. Displayed are mean values (n = 5) per group for a C enrichment from NaH13CO3 expressed as AP13C and b N enrichment from Na15NO3 expressed as AP15N after the pulse (5 h), chase3h (3 h after pulse), and chase6h (6 h after pulse). Both panels are depicted with broken y-axes to facilitate comparisons between less enriched samples. Treatments included light-incubated symbiotic medusae (SymL), dark-incubated symbiotic medusae (SymD), and light-incubated aposymbiotic medusae (ApoL). Error bars represent 95 % confidence intervals and dashed line natural isotope ratios (n = 5; 1.081 AP13C and 0.368 AP15N). Further shown are c the regression between host C enrichment and symbiont density expressed as AP13C for SymL (n = 15; y = 1.24 + 0.17x; r2Adj = 0.68, p < 0.001) and d the regressions between host 15N enrichment and medusae size expressed as AP15N from all treatments for chase3h (y = 0.3381 + 0.0014x; r2Adj = 0.67, p < 0.001) and chase6h (y = 0.3583 + 0.0004x; r2Adj = 0.86, p < 0.001; each n = 15)

In contrast to 13C, 15N enrichment was always higher in the host than in the algal fraction. AP15N in the algal fraction of SymL was slightly higher than in SymD indicating a possible link between nitrate assimilation and photosynthesis (pLME < 0.001). In the host fraction, 15N enrichment was highest at pulse (0.64–0.90) and dropped below 0.42 at chase for all treatments (Fig. 2b). At pulse, there were no significant differences between treatments (pANOVA > 0.05) (Additional File 3: Table S4), but ApoL samples experienced a larger drop in AP15N (i.e. N turnover rates) during the chase (pLME < 0.01; Fig. 2b). Notably, AP15N levels correlated significantly with medusa size for both chases when considering the host fractions from all treatments (r2Adj = 0.67 and 0.86 respectively, plm < 0.001 for both; Fig. 2d). However, the effect of medusa size seemed to be solely related to N turnover rates as there was no relationship between BD and AP15N after the pulse experiment (r2Adj = 0.04, plm > 0.05). AP15N values of the algal fraction in symbiotic individuals from both treatments peaked at the end of the chase (AP15Nchase6h > AP15Npulse and AP15Nchase6h > AP15Nchase3h; pLME < 0.001), in contrast to the pattern observed in the host fraction.

Organic carbon and nitrogen

Medusae were fed 13C and 15N labelled A. salina (Additional File 3: Table S5) to assess the cycling of heterotrophic nutrients in C. xamachana. Both the symbiont and the host fraction were enriched (APE host fraction > 1.19 and > 0.46, APE algal fraction > 1.12 and > 0.43 for 13C and 15N, respectively) and as expected prey enrichment level affected jellyfish enrichment (Additional File 3: Table S3). As direct consumer of the prey, the host showed higher enrichment levels than the algal fraction. Nevertheless, algal enrichment reached 36.7 ± 4.6 % of the host 13C and 70.3 ± 4.0 % of the host 15N enrichment highlighting fast and extensive elemental cycling.

Bacterial communities associated with C. xamachana

The bacterial microbiome of C. xamachana was dominated by Moraxellaceae (>60 %) and Pseudomonadaceae (~15-25 %) across all samples (Fig. 3a). Differences between samples were generally subtle, but ApoL3 contained a higher abundance of ‘others’, i.e. families with a comparably low abundance.

C. xamachana associated bacterial communities. a Stacked column plot representing the bacterial community composition associated with C. xamachana on the family level (SILVA database). Each colour represents one of the eight most abundant families; all 85 other families are grouped as ‘others’. b Clustering of C. xamachana samples based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity of bacterial community abundances in a non-metric multi-dimensional scaling plot (NMDS; stress value < 0.078). Circles indicate 95 % confidence ranges. c Boxplots of pairwise Bray-Curtis dissimilarities of samples within treatments. Statistical comparisons are based on Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test (chi2 = 21.5, df = 2, p < 0.001). Letters indicate significant differences of pairwise comparisons (pHolm < 0.01). Treatment abbreviations are same as in Fig. 2

Further, we assessed differences in the bacterial community structure among treatments by computing pairwise sample similarity (Bray-Curtis index) and displaying them in an nMDS biplot (Fig. 3b). ApoL samples showed slight differences to non-bleached treatments, which were significant (ApoL and SymL; pPERMANOVA = 0.036) or marginally non-significant (ApoL and SymD; pPERMANOVA = 0.068). A key difference, however, was within treatment heterogeneity in community composition (Fig. 3b, c). A comparison of within group community similarity across treatments revealed a much higher compositional heterogeneity in ApoL compared to the two treatments with symbiotic algae (Kruskal-Wallis Test; chi2= 21.463, df = 2, pWilcoxon < 0.01). On average, the number of reads, richness, Shannon and Simpson diversity, phylogenetic diversity (Faith), and evenness were lower in both symbiotic groups than in the aposymbiotic samples, which showed a markedly higher variability (i.e. standard deviation) for all measures (Table 1).

Moreover, we assessed ASVs based on their ubiquity as a potential indicator of their functional importance [53]. The core microbiome, i.e. the ASVs present in all 15 medusae, consisted of 10 ASVs, including 9 of the 10 most abundant taxa (Additional File 3: Table S2). The symbiome (ASVs occurring in all SymL and SymD samples; of note, the respective ASVs may be members of multiple ‘biomes’) consisted of 12 ASVs (Acinetobacter sp., Ruegeria sp., and the 10 core microbiome members). The apobiome also consisted of 12 ASVs (Cellvibrio sp., Ralstonia sp., and the 10 core microbiome members) (Additional File 3: Table S2).

Taxonomy-based functional profiling of bacterial communities in C. xamachana

Based on a METAGENassist analysis, we identified the 15 functional categories, which showed the largest differences across all bacterial microbiome samples (Fig. 4). Further, we used these categories to cluster all samples, which revealed a clear differentiation between aposymbiotic and symbiotic samples. Only ApoLPul4, the aposymbiotic sample with the lowest alpha diversity (expect evenness) (Table 1), was clustering more closely with the symbiotic than with the aposymbiotic samples. Differences included in particular a number of functions related to N metabolism. Functional traits that would limit inorganic N availability for the symbiotic algae, such as ammonium oxidizers and nitrite reducer were enriched in symbiotic microbiomes. On the other hand, nitrogen fixing, which potentially increases the nitrogen availability for the holobiont was depleted in symbiotic medusae. Further, an enrichment of sulphur oxidizers and a depletion of carbon fixers indicated lower O2 levels for microbiomes of symbiotic medusae (Fig. 4), which are required for effective N removal. Other functions like ‘degrades aromatic hydrocarbon’ and ‘xylan degraders’ were also more enriched in aposymbiotic sampled compared to ‘atrazine metabolism’ and ‘chitin degraders’ that were generally more depleted in these samples.

Predicted taxonomy-based functional differences of bacterial communities in C. xamachana. Enrichment is depicted in red and depletion in blue on a relative scale. Treatment abbreviations are same as in Fig. 2

Discussion

In this study, we assessed energy and nutrient dynamics in the Cassiopea xamachana holobiont to identify mechanisms that facilitate the maintenance of cnidarian-symbiodinian relationships under high nutrient conditions. The ability of C. xamachana to survive prolonged periods in an aposymbiotic state permitted us to disentangle the role of host and symbionts in nutrient dynamics, highlighting the value of C. xamachana as a model organism. Our results demonstrate that both autotrophically fixed and heterotrophically acquired C quickly cycled within the holobiont and was incorporated in both host and Symbiodiniaceae tissue. Nevertheless, heterotrophic feeding alone was not sufficient to cover the host’s needs and led to consistent weight loss. N assimilated from zooplankton prey was likewise shared among host and the algae. In contrast, inorganic N present in the surrounding water was effectively blocked off from Symbiodiniaceae. An analysis of host associated bacterial communities indicated that bacterial processes involved in N removal through ammonium oxidation and nitrite reductions were presumably enriched in the symbiotic hosts. Restricting the transmission of ambient DIN to Symbiodiniaceae can stabilize host-algal relationships in nutrient-rich environments and our data suggests that Cassiopea xamachana’s bacterial microbiome might play an important role in this process.

The fate of carbon

The daytime photosynthesis respiration ratio (Pg:R = 2) indicated that C fixation rates are sufficient to cover respiration even though they are lower—possibly due to handling stress—than previous measurements (2.04 for 24 h, including 12 h dark) [35]. As anticipated, light conditions facilitated the highest AP13C enrichment in Symbiodiniaceae and the host. Here, a large fraction of C was immediately transferred to the host (during the 5 h pulse), which is consistent with findings from coral holobionts [54]. Both host and symbiodinians maintained high 13C levels for at least 6 h, indicating an incorporation of C into cell tissues. In symbiotic holobionts, C transfer to the algae can be realized through respiration or in the form of organic C. Dissolved 13CO2 could diffuse into the host tissue and contribute to a ‘delayed enrichment’ (i.e. highest AP13C values after the 3 h chase) in our inorganic labelling experiment. Such dissolved CO2 pools utilized for photosynthesis were likely lost during sample preparation resulting in lower AP13C values in pulse samples.

In treatments lacking photosynthesis (SymD and ApoL treatments), 13C labelling also resulted in C assimilation, albeit at much lower rates (Fig. 2a). Baker et al. [24] explained host C enrichment in the dark by anaplerotic reactions that form intermediates of metabolic pathways including lipid synthesis and oxidation which could be performed by host and/or microbiome [55]. In the octocoral species assessed by Baker et al., however, the algal symbionts were not enriched after dark incubation. In C. xamachana, Symbiodiniaceae continued to accumulate C in the dark even after the pulse suggesting it originated from other holobiont members, in particular the host. Such C transfer from host to algae was also apparent from labelled Artemia and has been shown in coral from heterotrophic food sources [56, 57]. When bleached, the aposymbiotic holobiont enters a starvation mode that is characterized by a collapse in DIC uptake and cycling. Overall, C assimilation and (re)cycling was only effective in symbiotic C. xamachana holobionts under light conditions.

The fate of nitrogen

The uptake of inorganic N (15NO3−) showed distinctly different patterns from C assimilation. DIN uptake rates were much lower compared to DIC and we found a continuous AP15N decline in the host after the pulse for all treatments. All host samples (independent of state and treatment) showed a similarly strong initial enrichment after the pulse. Interestingly, this enrichment was followed by a pronounced drop in AP15N in all treatments, which correlated with medusa size and hence surface-to-volume ratio (i.e. larger medusae maintained higher AP15N level during both chases; Fig. 2d). Freeman et al. [36] found a similarly quick increase and depletion of 15N in C. xamachana incubated with 15NO3− and speculated that microbial activity could drive such high turn-over rates. The bacterial communities characterized here include abundant putative nitrogen cyclers (comprising nitrate reducers) that could contribute to the observed AP15N dynamics (see below). This pattern stands in stark contrast to coral host tissues, where 15N did not decrease over 14 days in a similar pulse-chase experiment [54], which indicates that corals are highly effective in N retention [17]. We argue that initial enrichment and subsequent size-correlated depletion in AP15N indicate a passive, concentration gradient driven movement of nitrate in and out of the host tissue that might work in concert with the associated prokaryotic community.

Importantly, the algal symbionts were unable to capitalize on available DIN indicating an effective control mechanism. N restriction as a mechanism of symbiont control has been suggested in coral and Exaiptasia as it is thought to maintain algal cell densities and ensure high rates of photosynthate translocation [20]. In corals, Tanaka et al. [54] found AP15N in the associated algae to be 4.7 times higher than in their hosts which highlights that only the algae are able to assimilate nitrate. In C. xamachana, however, the algal partners enrich slowly throughout the experiment, largely independent of the hosts 15N level. Overall low nitrate assimilation is in line with other ‘nutrient resistant’ cnidarian-symbiodinian associations. L. unguiculata [58] and Exaiptasia pulchella [59] removed none or only minimal nitrate from their surrounding water and δ15N enrichment from nitrate was not detectable in Exaiptasia [60] (notably, all of these are non-calcifying hosts and Exaiptasia spp. are not obligatory photosymbiotic). In other photosymbioses adapted to high nutrient concentrations, for instance Hydra viridissima [61] or Paramecium bursaria [62], some Chlorella endosymbionts have lost their assimilatory nitrate reduction pathway as an adaptation to symbiotic conditions. Such inability for nitrate uptake remains to be tested for C. xamachana’s algal partners. However, the host’s capacity to associate with several Symbiodiniaceae strains originating from ‘nutrient sensitive’ corals [30] argues for alternative mechanisms. Studies on such calcifying corals demonstrate that the photosymbionts were able to effectively assimilate nitrate and translocate it to their hosts in Acropora pulchra [63], A. tenuis [64], Orbicella faveolata [65], Porites cylindrica [54], and Stylophora pistillata [66]. Compared to C. xamachana, in a similar experimental setup (at similar C assimilation rates), the algal fraction of O. faveolata showed 15N enrichment two orders of magnitude greater (0.784 APE15N compared to 0.002 APE15N) and was remarkably higher than the host fraction enrichment [65]. In C. xamachana, Symbiodiniaceae are located in a symbiosome, a membrane complex wrapping the algal cells, which are predominantly situated in amoebocytes. While little is known about the function of (likely mobile) amoebocytes [31], the symbiosome is actively involved in nutrient transfer in Exaiptasia pallida and Acropora digitifera [67] and could be involved in restricting N access of the photosymbionts.

Unlike nitrate, organic 15N from labelled Artemia appeared freely transferable within C. xamachana, indicating that tight supply regulation might be specific for certain chemical forms. Heterotrophic or organic N, in contrast to nitrate, tends to improve health and metabolism in coral and may not harm the cnidarian-symbiodinian relationship [68, 69]. Ammonium, a metabolic waste product of the host, can also stimulate photosynthesis and carbon translocation to the host even under environmental stress and, importantly, as the preferred N source inhibit nitrate uptake in Symbiodiniaceae [66, 70]. By restricting access of external DIN for the algal symbionts and exerting control on the transfer of organic N and ammonium, the host presumably improves the holobionts (nutrient) resilience, which might be supported by the prokaryotic community (see below). Taken together, N cycling within the C. xamachana holobiont suggests an effective internal nitrate restriction of its algal associates, which might contribute to the high nutrient tolerance in C. xamachana.

The associated bacterial microbiome shares characteristics with other cnidarians

Prokaryotic associates contribute to nutrient cycling and interact directly with host and Symbiodiniaceae. Data on the associated bacterial communities (and disease) in C. xamachana are lacking. Other, asymbiotic scyphozoans host largely species-specific bacterial communities that differ from the environment, across body parts and life stages, and are involved in asexual reproduction, health, and fitness of the host [71,72,73,74].

The bacterial communities associated with C. xamachana were dominated by two ASVs (Acinetobacter sp. and Pseudomonas sp.) which made up 85 ± 2 % of all sequences in all samples but ApoLPul3 (66 %). These and other abundant taxa have been found to be associated with cnidarians before (e.g. Acinetobacter [75], Pseudomonas [76,77,78], Massilia [79], Sphingobium [80]). However, employing a sequence-based blastn search of the eleven most abundant ASVs did not yield associations with marine hosts. As to date most published data are OTU-based, we employed this approach for comparison with other cnidarian bacterial microbiomes (Additional File 2: Text S2). C. xamachana samples contained between 51 and 300 distinct OTUs which is in the same range (~100) as the cnidarian anemones E. pallida [78] and Hydra vulgaris [81] (Additional File 3: Table S6). In coral, the numbers are more variable depending on species and environmental conditions, but are generally in the order of tens to hundreds of OTUs [76, 82, 83]. Considering the best blastn hits for each OTU, we found that 9 of the 18 core microbiome member OTUs have previously been identified in corals and 5 in E. pallida (Additional File 3: Table S7). This highlights similarities in cnidarian holobiont and points towards bacterial taxa that are potentially conserved within the phylum.

Aposymbiotic samples seemed to host more variable bacterial communities illustrated by larger variations in the alpha diversity indices and a significantly larger within-treatment dissimilarity compared to both symbiotic groups (Table 1, Fig. 3c). Stressed coral tend to display higher community dissimilarity [84], though that is not always the case [85]. Stress may leave them more vulnerable to invasion and thus associations to otherwise untypical residents, which may increase alpha diversity [86]. In this study, a lack of nutrients in the aposymbiotic medusae could have similar effects. In particular, a lack of the obligate photosymbionts and therefore the main energy source might cause an unbalance of the associated microorganisms. Members of the symbiome may also be linked to the cnidarian-symbiodinian association as suggested for E. pallida [78]. Interestingly, the symbiome we identified comprised 12 members, which were also present in most aposymbiotic samples. This is surprising as Symbiodiniaceae are thought to maintain core microbiomes of their own [87], even in hospite [18, 88]. In this context, C. xamachana provides a system to readily test Symbiodiniaceae-Bacteria associations in an obligate symbiosis as the host can be infected with different algal species [30].

The role of the bacterial microbiome in holobiont nutrient cycling

The Symbiodiniaceae-Bacteria interactions have been hypothesized to be a hidden key for coral reef resilience [18]. Our data indicates that the majority of C. xamachana-associated Bacteria could be directly involved in nitrogen cycling and in particular denitrification. Based on a literature search, the 20 most abundant ASVs (Additional File 3, Table S2) belong to genera that can be linked to denitrification processes including Acinetobacter [89], Pseudomonas [90], Massilia [91], Sphingobium [92], Stenotrophomonas [93], Cellvibrio [94], Brevundimonas [95], Sphingomonas [96], Ralstonia [97], Cutibacterium (KEGG pathway Cutibacterium acnes KPA171202 [98]), Flavobacterium [99], and Ruegeria [100]. Further, Acinetobacter [89], Pseudomonas [90], Massilia [101], Sphingomonas [102], and Flavobacterium [99] have also been associated with nitrification processes and nitrifying bacteria have previously been linked to Cassiopea sp. [35]. These findings were supported by a sequence-based NCBI blastn search to assess putative functions. For the 20 most abundant ASVs, we identified 12 complete genomes at 100 % similarity to their respective amplicons, 6 at >99 %, and 2 at >97 %. All complete reference genomes included gene homologs presumably involved in N-cycling (Additional File 3: Table S8). Considering only genomes with 100 % match, 10 taxa contained at least one gene homolog potentially linked to denitrification. We further identified several gene homologs for nitrogen transport, ammonification, nitrification, and nitrogen fixation (Additional File 3: Table S8). Amplicon sequencing data are not quantitative and—like inferred functionality—should be interpreted with caution. However, the dominance of taxa presumably involved in nitrogen cycling and particularly denitrification is considerable. Both processes could be further supported by archaeal communities that were not assessed in this study [103]. While the pathways potentially involved remain to be elucidated (particularly considering oxygen sensitivity of nitrogenase; but see [104]), a combination of denitrifying, nitrifying, and ammonifying communities could effectively remove bioavailable N from the holobiont and support algal N limitation [22, 103, 105]. Future studies should target specifically functional genes to confirm and quantify N cycling processes (e.g. nitrite reductase nir, nitric oxide reductase nor, ammonia monooxygenase amo, and dinitrogenase reductase nif).

The associated bacterial communities further seem to contribute to holobiont N assimilation. In our study, 15N enrichment in the host tissue correlated positively with phylogenetic diversity of the associated bacterial community (Fig. 5). Of note, host (and algal) fraction measurements may include 15N that was assimilated by their associated prokaryotic community. However, based on the quick release of 15N after the chase (Fig. 2b), the holobionts’ overall assimilation of DIN is low and points towards a contribution of the microbial community. This positive relationship between bacterial phylogenetic diversity and 15N uptake rates fits well with the biodiversity-ecosystem functioning theory [106]. It has been shown that higher species numbers and phylogenetic diversity can enhance nutrient uptake and storage on an ecosystem level [107]. The data presented here hint that such a relationship might also exist within the holobiont/metaorganism concept.

Bacterial phylogenetic diversity affects host N assimilation. Regression: y = 0.667 + 0.368 x, r2Adj = 0.39, p < 0.01. n = 15, all sampled after pulse incubation. Treatment abbreviations are the same as in Fig. 2

Holobiont nutrient cycling changed fundamentally upon the cnidarian-symbiodinian dissociation after which the holobiont enters a starvation mode. The composition of associated bacteria also reflected the underlying physiological changes in medusa holobionts. Differences in the predicted functional profiles indicated that the bacterial communities changed from a nitrogen (‘ammonia oxidizer’, nitrite' reducer’, ‘sulphate reducer’) towards a sulphur (‘sulphur oxidizer’, ‘sulphide oxidizer’, ‘sulphur metabolism’)-based metabolism. This trend contrasts with findings on Exaiptasia where symbiotic polyps indicated higher sulphur metabolic activities, which was suggested to originate from Symbiodiniaceae derived dimethylsulphoniopropionate (DMSP) [78]. DMSP, however, is also present in (symbiotic) C. andromeda [108]. The enrichment of ‘ammonia oxidizer’ and ‘nitrite reducer’ in symbiotic C. xamachana indicates that biologically available N could be removed by the respective bacterial taxa supporting the algae’s nutrient limitation. This also contrasts findings in Exaiptasia where ‘nitrite reducer’ enriched in aposymbiotic samples [78]. While the predicted functional profiles corroborate nutrient deprivation in the medusae, the results should be interpreted with caution, as bacterial taxa putatively involved in N cycling were also dominant in aposymbiotic individuals (see above) and functional predictions remain putative. Future work employing metagenomics and metatranscriptomics may provide a more direct assessment of this relationship and the role of each holobiont member.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that different holobiont members contribute to nutrient cycling in C. xamachana. The host assimilates organic C and N and transfers both to its algal associates, which are restricted in DIN access. The obligate symbiosis with Symbiodiniaceae provides access to autotrophically fixed C that might contribute to energetically costly DIN assimilation. The cnidarian-symbiodinian association further facilitates effective C and N cycling. The associated bacterial communities seem to contribute to DIN uptake, which is correlated with their phylogenetic diversity and the host to DIN turnover (correlated with size). Nitrate levels in the host and algal partner indicate an internal strategy to limit algal N access that differs from other cnidarians (especially coral) and might help to explain the high nutrient tolerance peculiar to Cassiopea spp. While 15N stemming from DIN can quickly enrich and deplete in the host tissue, the photosymbionts’ access is limited. Nitrate restriction could be realized at the symbiosome, which should be addressed in future research. Additionally, the holobiont hosts a remarkable abundance of putatively N-cycling related (and denitrifying) bacteria that presumably remove N from the host tissue. The combination of host DIN control and microbial DIN removal might enable the jellyfish to thrive in nutrient rich waters in contrast to coral. Recent ‘coral probiotics’ approaches could test whether these bacteria may also increase coral resilience in eutrophied habitats [70].

Availability of data and materials

Sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession no. PRJNA627421 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/627421).

References

McFall-Ngai M, Hadfield MG, Bosch TCG, Carey H V, Domazet-Lošo T, Douglas AE, et al. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:3229–3236. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218525110

Sweet MJ, Bulling MT. On the importance of the microbiome and pathobiome in coral health and disease. Front Mar Sci 2017;4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00009

Rohwer F, Seguritan V, Azam F, Knowlton N. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 2002;243:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps243001

LaJeunesse TC, Parkinson JE, Gabrielson PW, Jeong HJ, Reimer JD, Voolstra CR, et al. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr Biol Cell Press; 2018;28:2570-2580.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.008

Rosenberg E, Koren O, Reshef L, Efrony R, Zilber-Rosenberg I. The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:355–362. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1635

Muscatine L, Porter JW. Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Bioscience . 1977;27:454–460. https://doi.org/10.2307/1297526

Burriesci MS, Raab TK, Pringle JR. Evidence that glucose is the major transferred metabolite in dinoflagellate – cnidarian symbiosis. J Exp Biol. 2012;215:3467–3477. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.070946

Davy SK, Allemand D, Weis VM. Cell biology of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:229–261. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.05014-11.

Verde E, McCloskey L. Production, respiration, and photophysiology of the mangrove jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana symbiotic with zooxanthellae:effect of jellyfish size and season. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 1998;168:147–162. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps168147

Muscatine L, Falkowski PG, Porter JW, Dubinsky Z. Fate of photosynthetic fixed carbon in light-adapted and shade-adapted colonies of the symbiotic coral Stylophora pistillata. Proc R Soc Ser B-Biological Sci. 1984.222:181–202. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1984.0058

Costanza R, D’Arge R, De Groot R, Farber S, Grasso M, Hannon B, et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature. 1997 387:253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/387253a0 Nature Publishing Group.

Weis VM. Cellular mechanisms of Cnidarian bleaching: stress causes the collapse of symbiosis. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:3059–3066. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.009597

Brown BE. Coral bleaching: causes and consequences. Coral Reefs. 1997;16:S129–S138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003380050249

Buddemeier RW, Fautin DG. Coral bleaching as an adaptive mechanism - a testable hypothesis. Bioscience. 1993;43:320–326. https://doi.org/10.2307/1312064

Hughes TP, Kerry JT, Baird AH, Connolly SR, Dietzel A, Eakin CM, et al. Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature. 2018;556:492–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0041-2

Vega Thurber RL, Burkepile DE, Fuchs C, Shantz AA, McMinds R, Zaneveld JR. Chronic nutrient enrichment increases prevalence and severity of coral disease and bleaching. Glob Chang Biol. 2014;20:544–554. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12450

Rädecker N, Pogoreutz C, Voolstra CR, Wiedenmann J, Wild C. Nitrogen cycling in corals: The key to understanding holobiont functioning? Trends Microbiol. 2015;490–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.008.

Matthews JL, Raina J, Kahlke T, Seymour JR, Oppen MJH, Suggett DJ. Symbiodiniaceae-bacteria interactions: rethinking metabolite exchange in reef-building corals as multi-partner metabolic networks. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22:1675–1687. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14918.

Benavides M, Bednarz VN, Ferrier-Pagès C. Diazotrophs: Overlooked key players within the coral symbiosis and tropical reef ecosystems? Front Mar Sci. 2017;4:10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00010

Cui G, Liew YJ, Li Y, Kharbatia N, Zahran NI, Emwas A-H, et al. Host-dependent nitrogen recycling as a mechanism of symbiont control in Aiptasia. Plos Genet. 2019;15:e1008189. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008189 Krediet CJ, editor.

Wiedenmann J, D’Angelo C, Smith EG, Hunt AN, Legiret F-E, Postle AD, et al. Nutrient enrichment can increase the susceptibility of reef corals to bleaching. Nat Clim Chang. 2013;3:160–164. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1661

Tilstra A, El-Khaled YC, Roth F, Rädecker N, Pogoreutz C, Voolstra CR, et al. Denitrification Aligns with N2 Fixation in Red Sea Corals. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55408-z

Conti-Jerpe IE, Thompson PD, Wong CWM, Oliveira NL, Duprey NN, Moynihan MA, et al. Trophic strategy and bleaching resistance in reef-building corals. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz5443. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5443

Baker DM, Freeman CJ, Knowlton N, Thacker RW, Kim K, Fogel ML. Productivity links morphology, symbiont specificity and bleaching in the evolution of Caribbean octocoral symbioses. ISME J. 2015;9:2620-2629 https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.71

Wooldridge SA. Breakdown of the coral-algae symbiosis: towards formalising a linkage between warm-water bleaching thresholds and the growth rate of the intracellular zooxanthellae. Biogeosciences. 2013;10:1647–1658. https://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-1647-2013

Stoner EW, Yeager LA, Sweatman JL, Sebilian SS, Layman CA. Modification of a seagrass community by benthic jellyfish blooms and nutrient enrichment. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol. 2014;461:185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2014.08.005

Niggl W, Wild C. Spatial distribution of the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea sp. within fringing coral reef environments of the Northern Red Sea: implications for its life cycle. Helgol Mar Res. 2010;64:281–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-009-0181-8

Ohdera AH, Abrams MJ, Ames CL, Baker DM, Suescún-Bolívar LP, Collins AG, et al. Upside-down but headed in the right direction: review of the highly versatile Cassiopea xamachana system. Front Ecol Evol. 2018;6:35. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00035

Rädecker N, Pogoreutz C, Wild C, Voolstra CR. Stimulated Respiration and Net Photosynthesis in Cassiopeia sp. during Glucose Enrichment Suggests in hospite CO2 Limitation of Algal Endosymbionts. Front Mar Sci. 2017;4:267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00267.

Newkirk CR, Frazer TK, Martindale MQ, Schnitzler CE. Adaptation to Bleaching: are Thermotolerant Symbiodiniaceae strains more successful than other strains under elevated temperatures in a model symbiotic Cnidarian? Front Microbiol. 2020;11:822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00822.

Estes AM, Kempf SC, Henry RP. Localization and quantification of carbonic anhydrase activity in the symbiotic scyphozoan Cassiopea xamachana. Biol Bull. 2003;204:278–289. https://doi.org/10.2307/1543599

Kremer P. Ingestion and elemental budgets for Linuche unguiculata, a scyphomedusa with zooxanthellae. J Mar Biol Assoc. 2005;85:613–625. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315405011549

McGill CJ, Pomory CM. Effects of bleaching and nutrient supplementation on wet weight in the jellyfish Cassiopea xamachana (Bigelow) (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa). Mar Freshw Behav Physiol. 2008;41:179–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/10236240802369899

Mortillaro JM, Pitt KA, Lee SY, Meziane T. Light intensity influences the production and translocation of fatty acids by zooxanthellae in the jellyfish Cassiopea sp. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol. 2009;378:22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2009.07.003

Welsh DT, Dunn RJK, Meziane T. Oxygen and nutrient dynamics of the upside-down jellyfish (Cassiopea sp.) and its influence on benthic nutrient exchanges and primary production. Hydrobiologia. 2009;635:351–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-009-9928-0

Freeman C, Stoner E, Easson C, Matterson K, Baker D. Variation in δ13C and δ15N values suggests a coupling of host and symbiont metabolism in the Symbiodinium-Cassiopea mutualism. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2017;571:245–251. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12138

Ohdera A, Ames CL, Dikow RB, Kayal E, Chiodin M, Busby B, et al. Box, stalked, and upside-down? Draft genomes from diverse jellyfish (Cnidaria, Acraspeda) lineages: Alatina alata (Cubozoa), Calvadosia cruxmelitensis (Staurozoa), and Cassiopea xamachana (Scyphozoa). GigaScience. 2019;8:giz069. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz069 Oxford Academic.

Matthews JL, Sproles AE, Oakley CA, Grossman AR, Weis VM, Davy SK. Menthol-induced bleaching rapidly and effectively provides experimental aposymbiotic sea anemones (Aiptasia sp.) for symbiosis investigations. J Exp Biol. 2016;219:306–310. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.128934

Al-Horani FA, Al-Moghrabi SM, Beer D. The mechanism of calcification and its relation to photosynthesis and respiration in the scleractinian coral Galaxea fascicularis. Mar Biol. 2003;142:419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-002-0981-8

Fry B. Stable isotope ecology. Springer; 2006. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/0-387-33745-8.

Team RDC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. Available from: http://www.r-project.org

Coffroth MA, Lasker HR, Diamond ME, Bruenn JA, Bermingham E. DNA fingerprints of a gorgonian coral: a method for detecting clonal structure in a vegetative species. Mar Biol. 1992;114:317–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00349534

Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Backhed F, Nyren P, Engstrand L. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2836. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002836

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, Bokulich NA, Abnet CC, Al-Ghalith GA, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–857. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools, Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–D596, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks1219

Hsieh TC, Ma KH, Chao A. iNEXT: an R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol Evol. 2016;7:1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12613

Faith DP. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol Conserv. 1992;61:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(92)91201-3

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’hara RB, et al. Package ‘vegan’. Community Ecol Package. 2013;2(9):1–295.

Wickham H. Ggplot2. Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput Stat. 2011; 3(2): 180-185. https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.147

Arndt D, Xia J, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Guo AC, Cruz JA et al. METAGENassist: a comprehensive web server for comparative metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W88–W95. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks497

Hackstadt AJ, Hess AM Filtering for increased power for microarray data analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009; 10,11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-11

Ainsworth T, Krause L, Bridge T, Torda G, Raina J-B, Zakrzewski M, et al. The coral core microbiome identifies rare bacterial taxa as ubiquitous endosymbionts. ISME J. 2015;9:2261–2274. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2015.39

Tanaka Y, Miyajima T, Koike I, Hayashibara T, Ogawa H. Translocation and conservation of organic nitrogen within the coral-zooxanthella symbiotic system of Acropora pulchra, as demonstrated by dual isotope-labeling techniques J Exp Mar Bio Ecol. 2006;336:110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2006.04.011

Alonso-Sáez L, Galand PE, Casamayor EO, Pedrós-Alió C, Bertilsson S. High bicarbonate assimilation in the dark by Arctic bacteria. ISME J. 2010;4:1581–1590. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.69

Tremblay P, Maguer JF, Grover R, Ferrier-Pages C. Trophic dynamics of scleractinian corals: Stable isotope evidence. J Exp Biol. 2015;218:1223–1234. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2010.69

Hughes A, Grottoli A, Pease T, Matsui Y. Acquisition and assimilation of carbon in non-bleached and bleached corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2010;420:91–101. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08866

Wilkerson FP, Kremer P. DIN, DON and PO~ 4 flux by a medusa with algal symbionts. Mar Ecol Ser. 1993;90:237-250. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps090237

Wilkerson FP, Muscatine L. Uptake and assimilation of dissolved inorganic nitrogen by a symbiotic sea anemone. Proc R Soc London Ser B Biol Sci. 1984;221:71–86. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1984.0023

Sproles AE. Nutritional Interactions in the Cnidarian-Dinoflagellate Symbiosis and their Role in Symbiosis Establishment. 2017. PhD Thesis. Victoria University of Wellington. http://hdl.handle.net/10063/6646

Hamada M, Schröder K, Bathia J, Kürn U, Fraune S, Khalturina M, et al. Metabolic co-dependence drives the evolutionarily ancient Hydra–Chlorella symbiosis. Elife. 2018;7 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.35122.001.

Kamako SI, Hoshina R, Ueno S, Imamura N. Establishment of axenic endosymbiotic strains of Japanese Paramecium bursaria and the utilization of carbohydrate and nitrogen compounds by the isolated algae. Eur J Protistol. 2005;41:193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejop.2005.04.001

Tanaka Y, Suzuki A, Sakai K. The stoichiometry of coral-dinoflagellate symbiosis: Carbon and nitrogen cycles are balanced in the recycling and double translocation system. ISME J. 2018;12:860–868. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-017-0019-3.

Baker DM, Andras JP, Jordán-Garza AG, Fogel ML. Nitrate competition in a coral symbiosis varies with temperature among Symbiodinium clades. ISME J. 2013;7:1248–1251. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.12

Baker DM, Freeman CJ, Wong JCY, Fogel ML, Knowlton N. Climate change promotes parasitism in a coral symbiosis. ISME J. 2018;12:921–930. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-018-0046-8

Grover R, Maguer J-F, Allemand D, Ferrier-Pagés C. Nitrate uptake in the scleractinian coral Stylophora pistillata. Limnol Oceanogr. 2003;48:2266–2274. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2003.48.6.2266.

Hambleton EA, Jones VAS, Maegele I, Kvaskoff D, Sachsenheimer T, Guse A. Sterol transfer by atypical cholesterol-binding NPC2 proteins in coral-algal symbiosis. eLife. 2019;8:e43923. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.43923

Grottoli AG, Rodrigues LJ, Palardy JE. Heterotrophic plasticity and resilience in bleached corals. Nature. 2006;440:1186–1189. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04565

Fernandes de Barros Marangoni L, Ferrier-Pagès C, Rottier C, Bianchini A, Grover R. Unravelling the different causes of nitrate and ammonium effects on coral bleaching. Sci Rep. 2020;10,11975 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68916-0

Morris LA, Voolstra CR, Quigley KM, Bourne DG, Bay LK. Nutrient Availability and Metabolism Affect the Stability of Coral–Symbiodiniaceae Symbioses. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27,8:678-689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2019.03.004

Lee MD, Kling JD, Araya R, Ceh J. Jellyfish life stages shape associated microbial communities, while a core microbiome is maintained across all. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01534

Ovchinnikova T V., Balandin S V., Aleshina GM, Tagaev AA, Leonova YF, Krasnodembsky ED, et al. Aurelin, a novel antimicrobial peptide from jellyfish Aurelia aurita with structural features of defensins and channel-blocking toxins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:514–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.078

Tinta T, Kogovšek T, Klun K, Malej A, Herndl GJ, Turk V. Jellyfish-Associated Microbiome in the Marine Environment: Exploring Its Biotechnological Potential. Mar Drugs. 2019;17:94. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17020094

Weiland-Bräuer N, Pinnow N, Langfeldt D, Roik A, Güllert S, Chibani CM, et al. The Native Microbiome is Crucial for Offspring Generation and Fitness of Aurelia aurita. MBio. 2020;11:e02336-e02320. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02336-20

Koren O, Rosenberg E. Bacteria associated with the bleached and cave coral Oculina patagonica. Microb Ecol. 2008;55,523–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-007-9297-z

Röthig T, Yum LK, Kremb SG, Roik A, Voolstra CR. Microbial community composition of deep-sea corals from the Red Sea provides insight into functional adaption to a unique environment. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44714. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44714

Röthig T, Ochsenkühn MA, Roik A, van der Merwe R, Voolstra CR. Long-term salinity tolerance is accompanied by major restructuring of the coral bacterial microbiome. Mol Ecol. 2016;25:1308–1323. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13567

Röthig T, Costa RM, Simona F, Baumgarten S, Torres AF, Radhakrishnan A, et al. Distinct bacterial communities associated with the coral model Aiptasia in aposymbiotic and symbiotic states with Symbiodinium. Front Mar Sci. 2016;3:23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2016.00234

Yang S-H, Tseng C-H, Huang C-R, Chen C-P, Tandon K, Lee STM, et al. Long-term survey is necessary to reveal various shifts of microbial composition in corals. Front Microbiol 2017;8:1094. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01094

Hadaidi G, Röthig T, Yum LK, Ziegler M, Arif C, Roder C, et al. Stable mucus-associated bacterial communities in bleached and healthy corals of Porites lobata from the Arabian Seas. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45362. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45362

Franzenburg S, Fraune S, Altrock PM, Künzel S, Baines JF, Traulsen A, et al. Bacterial colonization of Hydra hatchlings follows a robust temporal pattern. ISME J. 2013;7:781–790. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.156

Hernandez-Agreda A, Leggat W, Bongaerts P, Herrera C, Ainsworth TD. Rethinking the coral microbiome: simplicity exists within a diverse microbial biosphere. MBio. 2018;9:e00812-e00818. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00812-18

Röthig T, Bravo H, Corley A, Prigge T-L, Chung A, Yu V, et al. Environmental flexibility in Oulastrea crispata in a highly urbanised environment: a microbial perspective. Coral Reefs. 2020; 9:649–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-020-01938-2

Zaneveld JR, McMinds R, Vega Thurber R. Stress and stability: applying the Anna Karenina principle to animal microbiomes. Nat Microb. 2017;2:17121. http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.121

Sweet M, Burian A, Fifer J, Bulling M, Elliott D, Raymundo L. Compositional homogeneity in the pathobiome of a new, slow-spreading coral disease. Microbiome 2019;7:139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0759-6

McDevitt-Irwin JM, Baum JK, Garren M, Vega Thurber RL. Responses of coral-associated bacterial communities to local and global stressors. Front Mar Sci. 2017;4:262. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00262

Lawson CA, Raina J-B, Kahlke T, Seymour JR, Suggett DJ. Defining the core microbiome of the symbiotic dinoflagellate, Symbiodinium. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2018;10:7–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.12599

Bernasconi R, Stat M, Koenders A, Huggett MJ. Global Networks of Symbiodinium-Bacteria within the Coral Holobiont. Microb Ecol. 2018;1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-018-1255-4

Yao S, Ni J, Ma T, Li C. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification at low temperature by a newly isolated bacterium, Acinetobacter sp. HA2. Bioresour Technol. 2013;139:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.189

Zhang J, Wu P, Hao B, Yu Z. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification by the bacterium Pseudomonas stutzeri YZN-001. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:9866–9869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.07.118

Zhao X, Li X, Qi N, Gan M, Pan Y, Han T, et al. Massilia neuiana sp. nov., isolated from wet soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:4943–4947. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.002333

Fang W, Wang X, Huang B, Zhang D, Liu J, Zhu J, et al. Comparative analysis of the effects of five soil fumigants on the abundance of denitrifying microbes and changes in bacterial community composition. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;187:109850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109850

Yu L, Liu Y, Wang G. Identification of novel denitrifying bacteria Stenotrophomonas sp. ZZ15 and Oceanimonas sp. YC13 and application for removal of nitrate from industrial wastewater. Biodegradation. 2009;20:391–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10532-008-9230-2

Li J, Wang JT, Hu HW, Cai ZJ, Lei YR, Li W, et al. Changes of the denitrifying communities in a multi-stage free water surface constructed wetland. Sci Total Environ. 2019;650:1419–1425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.123

Tsubouchi T, Koyama S, Mori K, Shimane Y, Usui K, Tokuda M, et al. Brevundimonas denitrificans sp. nov., a denitrifying bacterium isolated from deep subseafloor sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:3709–3716. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.067199-0.

Cua LS, Stein LY. Characterization of denitrifying activity by the alphaproteobacterium, Sphingomonas wittichii RW1. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00404

Zumft WG. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:533–616 PMCID: PMC232623.

Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000:27–30 [cited 2020 Nov 18] Available from: http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg/.

Castignetti D, Hollocher TC. Heterotrophic nitrification among denitrifiers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:620–623. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.47.4.620-623.1984

Arahal DR, Lucena T, Rodrigo-Torres L, Pujalte MJ. Ruegeria denitrificans sp. Nov., a marine bacterium in the family rhodobacteraceae with the potential ability for cyanophycin synthesis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:2515–2522. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.002867

Qiao Z, Sun R, Wu Y, Hu S, Liu X, Chan J. Microbial heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification dominates simultaneous removal of aniline and ammonium in aquatic ecosystems. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020;231:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-020-04476-3

Xie CH, Yokota A. Sphingomonas azotifigens sp. nov., a nitrogen-fixing bacterium isolated from the roots of Oryza sativa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:889–893. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.64056-0

Siboni N, Ben-Dov E, Sivan A, Kushmaro A. Global distribution and diversity of coral-associated Archaea and their possible role in the coral holobiont nitrogen cycle. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2979–2990. http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01718.x

Babbin AR, Tamasi T, Dumit D et al. Discovery and quantification of anaerobic nitrogen metabolisms among oxygenated tropical Cuban stony corals. ISME J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00845-2

Yoon S, Cruz-García C, Sanford R, Ritalahti KM, Löffler FE. Denitrification versus respiratory ammonification: Environmental controls of two competing dissimilatory NO 3-/NO 2-reduction pathways in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4. ISME J. 2015;9:1093–1104. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.201

Tilman D, Wedin D, Knops J. Productivity and sustainability influenced by biodiversity in grassland ecosystems. Nature. 1996;379:718–720. https://doi.org/10.1038/379718a0

Cardinale BJ. Biodiversity improves water quality through niche partitioning. Nature. 2011;472:86–91. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09904

Yancey PH, Heppenstall M, Ly S, Andrell RM, Gates RD, Carter VL, et al. Betaines and dimethylsulfoniopropionate as major osmolytes in cnidaria with endosymbiotic dinoflagellates. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2010;83:167–173. https://doi.org/10.1086/644625

Acknowledgements

We thank Acacia Tsz So Tang, Jordan Pierce, and Jonathan Cybulski for valuable support during the experiments and James Hagan for advice on the statistical analysis. The ITS2 primers were designed by Jean-François Flot and Monica Medina supplied the C. xamachana strain (polyps). We acknowledge Aki Ohdera and Victoria Sharp’s support in establishing DNA extraction protocols. We thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by the University of Hong Kong, Faculty of Science, Division of Ecology and Biodiversity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GP, JCYW, TR, and WM designed and conceived the experiments. GP, TR, AB, JCYW, and WM generated, analysed, and interpreted the data. DMB contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. TR, GP, and JCYW wrote the first draft; all authors contributed to the final manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1

. Effects of menthol bleaching on C. xamachana. (a) Photosynthetic efficiency throughout menthol exposure (day 1-4) and bleaching process. n = 12; Imaging-PAM (Walz, Germany); Fo: dark-adapted minimal fluorescence yields; Fm: dark-adapted maximal fluorescence yield; Fv/Fm: maximum quantum yield. (b) Response of bell diameter (BD) and wet weight (WW) to bleaching (mean, n = 12). (c) Visualization of photosynthetic efficiency (i.e. Fo, Fm, and Fv/Fm). Figure S2. Relationship between wet weight (WW) and bell diameter (BD) in (a) symbiotic (n = 35) [WWsymbiotic = 8.540 -0.494*BD + 0.009*BD2] and (b) aposymbiotic C. xamachana (n = 12) [WWaposymbiotic = -1.440 + 0.100*BD]. Different colours indicate the number of days after start of the four-day menthol bleaching. Dashed vertical lines indicate minimum and maximum BD of medusae employed in the pulse-chase experiment. Figure S3. Net primary production (Pn) and host carbon enrichment. Host fraction enrichment expressed as AP13C light-incubated medusae (SymL) from all incubations (pulse, chase 3h and chase 6h) (n = 15).

Additional file 2: Text S1.

Extended Material and Methods. Text S2. OTU based bacterial analysis.

Additional file 3: Table S2.