Abstract

Background

Giant clams and scleractinian (reef-building) corals are keystone species of coral reef ecosystems. The basis of their ecological success is a complex and fine-tuned symbiotic relationship with microbes. While the effect of environmental change on the composition of the coral microbiome has been heavily studied, we know very little about the composition and sensitivity of the microbiome associated with clams. Here, we explore the influence of increasing temperature on the microbial community (bacteria and dinoflagellates from the family Symbiodiniaceae) harbored by giant clams, maintained either in isolation or exposed to other reef species. We created artificial benthic assemblages using two coral species (Pocillopora damicornis and Acropora cytherea) and one giant clam species (Tridacna maxima) and studied the microbial community in the latter using metagenomics.

Results

Our results led to three major conclusions. First, the health status of giant clams depended on the composition of the benthic species assemblages. Second, we discovered distinct microbiotypes in the studied T. maxima population, one of which was disproportionately dominated by Vibrionaceae and directly linked to clam mortality. Third, neither the increase in water temperature nor the composition of the benthic assemblage had a significant effect on the composition of the Symbiodiniaceae and bacterial communities of T. maxima.

Conclusions

Altogether, our results suggest that at least three microbiotypes naturally exist in the studied clam populations, regardless of water temperature. These microbiotypes plausibly provide similar functions to the clam host via alternate molecular pathways as well as microbiotype-specific functions. This redundancy in functions among microbiotypes together with their specificities provides hope that giant clam populations can tolerate some levels of environmental variation such as increased temperature. Importantly, the composition of the benthic assemblage could make clams susceptible to infections by Vibrionaceae, especially when water temperature increases.

Video abstract.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Giant clams (Hippopus and Tridacna genera) are emblematic and keystone species of Indo-West Pacific coral reef ecosystems. These filter-feeding organisms play a wide range of ecological roles: their calcium carbonate shell is a substrate for colonization, they provide food for numerous reef organisms, act as a shelter, and contribute to primary production on the reef [1, 2]. Like some other marine bivalves, giant clams live in close partnership with unicellular dinoflagellate algae from the family Symbiodiniaceae [3, 4] that satisfy the majority of the clams’ carbon and energy needs [5, 6]. This partnership with Symbiodiniaceae is established horizontally (acquired from the environment), only after metamorphosis from larva to juvenile [7]. Formerly known as nine clades of a single dinoflagellate genus (Symbiodinium [8]), seven clades have recently been re-classified to the genus level [9]. Microbiome profiling studies using the ITS2 and/or the LSU nuclear and chloroplast markers have recorded clade A (genus Symbiodinium), C (genus Cladocopium), D (genus Durusdinium), and G (genus Gerakladium) in giant clams [10,11,12]. These genera are also found in cnidarians [13, 14], but in contrast to the typically intracellular symbiosis with corals, algae reside in the clams’ siphonal mantle extracellularly [7].

Giant clams can harbor one single algal genus or an assemblage of multiple genera [10, 15]. While Tridacna crocea is predominantly associated with one algal genus at a time (Symbiodinium, Cladocopium, or, less frequently, Durusdinium), Tridacna squamosa and Tridacna maxima typically harbor multiple genera simultaneously [10, 11], except in the Red Sea where they exclusively associate with Symbiodinium spp. [16]. This species-specific symbiosis with Symbiodiniaceae can be disrupted by environmental change that—similar to corals—can lead the expulsion or apoptosis of the photosynthetic symbionts [17,18,19,20] and cause clam bleaching and, subsequently, death. Indeed, mass bleaching and mortality of giant clams related to thermal stress and high solar irradiance, often associated with extremely low tides, have been recorded in the past [21, 22]. Bleaching has been widely studied in Scleractinia, and it has been shown that the composition of the Symbiodiniaceae community in corals shifts in response to environmental changes [23,24,25,26]. However, this is a complex system, and data on the stable partnership between adult corals and newly acquired Symbiodiniaceae are still lacking [27, 28]. Contrary to corals, however, only few studies have scrutinized the nature of the symbiosis between Symbionidaceae and tridacnids. DeBoer and collaborators [10] showed that giant clams that harbor Symbiodinium (formerly known as “clade A”), a typical temperature- and light-resistant algal genus in corals, are more sensitive to thermal and light stress than those that harbor Cladocopium. This result is, however, inconsistent with a recent report on tridacnids of the Red Sea, where Symbiodinium was found as the unique algal genus in clams that lived in high temperature and salinity conditions [16]. The role and potential flexibility of the Symbiodiniaceae assemblage of giant clams need clarification in order to better understand the threats and adaptive capacity of these important reef organisms.

It is increasingly recognized that symbiotic microorganisms other than Symbiodiniaceae also greatly contribute to the physiological performance of complex marine metaorganisms, such as the coral holobiont [29], or, plausibly, giant clams. The prokaryotic microbial community, for example, plays a significant role in the coral’s nutrient cycling and immune defense (reviewed in [30, 31]). Similarly to the Symbiodiniaceae community, the composition of the prokaryotic microbial community can change with the coral’s environment [32,33,34,35,36] even though this is not supported by all studies [37, 38]. Bacterial community changes are not always beneficial; however, opportunistic pathogenic taxa, such as Vibrionaceae, can colonize corals and lead to coral disease and the death of the colony [35, 39, 40]. While the abundance of metagenomic studies on corals describes the diversity of microbes in the coral holobiont, their exact roles and functions remain unclear [41, 42]. Even less is known about the prokaryotic community of bivalves, where most microbial studies have focused on pathogenic bacteria that cause disease or mortality [43,44,45] or pose a human health risk via direct consumption [43, 46, 47]. Bivalves filter through large volumes of water for feeding and hence accumulate a diverse suite of microorganisms that are not directly associated with their normal physiology, making it particularly challenging to understand the composition and role of the clam core microbiome. Only one study has recently reported the bacterial composition of different tissues of Tridacninae [48]. Assuming a similarly important role of microbes in the healthy functioning and adaptive capacity of the bivalve holobiont as recognized in corals, it is critical to better understand what influences the composition of the clam microbiome.

While the initial establishment of the Symbiodiniaceae community occurs horizontally in the early stages of the giant clam’s life [7, 49], nothing is known about its bacterial community. In corals, it is well established that a part of its bacterial microbiome is vertically transmitted (passed on from parent to the offspring, e.g., [50, 51]) and part of it is acquired horizontally, and therefore highly depends on the environment (e.g., [32, 52]). The Symbiodiniaceae composition of the reef benthos has been found to influence the Symbiodiniaceae composition of some symbiotic metazoans, e.g., nudibranchs [53]. Furthermore, the associated bacteria and Archaea of coral species have also been shown to vary according to the presence of certain marine organisms (e.g., macroalgae [54]) or their absence (e.g., decrease of coral cover and overfishing [55]). Thus, the environmental microbiome (dinoflagellate algae as well as prokaryotes) that is available for uptake might also greatly depend on the surrounding existing benthic communities. To test the importance of the benthic assemblage composition on the makeup of the giant clam’s microbiome as well as their physiological performance, we created artificial coral reef assemblages comprising of the clam Tridacna maxima and two common Indo-Pacific scleractinian coral species, Pocillopora damicornis and Acropora cytherea. The fitness of T. maxima was monitored in different assemblages under control and increased water temperature conditions, and its associated bacterial and algal communities were characterized using 16S, ITS2, and 23S profiling.

Results

Mortality of giant clams

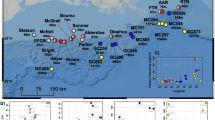

Some mortality of T. maxima was observed during the experiments (Fig. 1; Additional file 1). During the 12 days of the acclimation period, no mortality was observed in T assemblages (four aquaria), and some mortality of clams was observed in three of four aquaria with AT assemblages and one of four aquaria with PAT assemblages. A logit analysis did not reveal significant differences in mortality rate among assemblages (p = 0.9263) with a range of response (death probability) from 8.3 10–2 to 6.3 10–2 and 5.4 10–10 for AT, PAT, and T. During the 5 days following acclimation, clam mortality was observed with frequencies varying according to thermal conditions (L or S) and assemblage composition (p = 0.003). Mortality was highest for AT (L and S) and PAT (S) assemblages with a range of response of 0.33, 0.39, and 0.71.

Mortality rates of giant clams in three experimental benthic assemblages during the acclimation period and during the experimental period. Each circle represents one aquarium. PAT, P. damicornis, A. cytherea, and T. maxima; AT, A. cytherea and T. maxima; PT, T. maxima; T, P. damicornis and T. maxima; L, lagoon temperature; S, thermal stress; a–c, aquarium for each assemblage and conditions

The bacterial community of giant clams

The microbiome of 36 giant clams was characterized. Due to mortality, sample numbers differ among experimental conditions (number of analyzed giant clams: n = 8 in T at the end of acclimation (T0) and n = 3 in AT.L, n = 3 in AT.S, n = 6 in PAT.L, n = 4 in PAT.S, n = 6 in T.L, and n = 6 in T.S at day 17 (T1)). Seven individuals showed signs of declining health (decrease in closure reactivity, loss of color, and mantle degradation) and therefore were further labeled as “dying.”

The 16S DNA gene libraries yielded 716,100 sequences from which 693,609 sequences (8911–33,115 per sample) were selected with an average length of 448 bp. The selected sequences were assigned to 43 phyla subdivided in 415 bacterium families (Additional file 2). The family-level pairwise correlation of microbiomes among samples yielded four distinct microbial community clusters, hereafter referred to as microbiotypes (Fig. 2). The microbiotypes did not correlate with neither the composition of the experimental assemblages (chi-squared test, Monte Carlo p = 0.14) nor the thermal conditions (p = 0.12). However, one microbiotype (Md) was exclusively characteristic of dying clams (five of seven dying clams shared this microbiotype). Two further dying clams did not cluster under Md, but instead fell into the microbiotype M1 (T2.S.1) and M3 (PAT1.L.1), while also sharing similarities with Md, as well as two other healthy clams from the S treatment (T2.S.2; T2.S.3). Most of the diversity has been covered in every cluster even though the representation of the microbial community is not fully complete, for some samples (Additional file 3). The number of detected species was significantly positively correlated with the number of reads in the sample (Pearson correlation test, 0.35; p = 0.03).

Heatmap from the pairwise correlation between microbiomes of clams in experimental benthic communities and at control and elevated temperature. PAT, P. damicornis, A. cytherea, and T. maxima; AT, A. cytherea and T. maxima; T, T. maxima; 0, control; (1–3), experiment number; L, lagoon temperature; S, thermal stress; (1–4), sample number. M, microbial community clusters (microbiotypes); Md, dying clam microbiotype; 1–3, clam microbiotype number. Dying clam names are in bold

Bacterial species richness measured by chao1 (Additional file 4) ranged from 1205 to 5934 per sample, with the lowest average bacterial species richness found in M1 (1682 ± 366). The average index of bacterial species richness was slightly higher in Md (2386 ± 1922) and increased greatly in M3 and M2 (3057 ± 1344 and 3294 ± 1363, respectively). Thus, significant differences were determined between M1 and M2–M3 (pM1:M2 = 0.0072; pM1:M3 = 0.0056). Species diversity, measured by the Inverse Simpson Index (Additional file 4), ranged from six to nine in microbiotypes M1, M3, and Md and was significantly different from M2 (56.5; pM1:Md = 0.0018; pM1:M2 = 0.0013; pM1:M3 = 0.0005).

The most abundant bacterial family in the Md microbiotype was Vibrionaceae (Fig. 3; > 35% on average), and within that, Catenococcus spp. were present in four samples (T1.L1, 89.9%; PAT1.S.1, 83.2%; PAT1.S.4, 67%; and PAT1.S.3, 58.5%). The M1 microbiotype was characterized by a higher proportion of Rhodobacteraceae (57.4%) and a lower proportion of Gammaproteobacteria (20.4%). The M2 microbiotype was dominated by Moraxellaceae (71.2%) and an unclassified Gammaproteobacteria (21.1%). The M3 microbiotype harbored a higher level of Gammaproteobacteria (53.7%) combined with a higher abundance of Hahellaceae (73%).

Relative abundance of the 18 most abundant bacterial families in giant clams T. maxima grouped by microbiotype; 396 less abundant taxa are grouped under “others.” Abbreviations of experimental assemblages: PAT, P. damicornis, A. cytherea, and T. maxima; AT, A. cytherea and T. maxima; T, T. maxima; 0, control; (1–3), experiment number; L, lagoon temperature; S, thermal stress; (1–4), sample number; D, dying clam; H, healthy clam; M, microbiotypes; Md, dying clam microbiotype; 1–3, clam microbiotype number

Bacterial functional roles

To scrutinize putative functional differences of bacterial communities of T. maxima in experimental treatments, we applied a taxonomy-based profiling using METAGENassist (Fig. 4) and PICRUSt2 (Additional file 5). This functional clustering clearly distinguished Md, M1, M2, and M3 microbiotype according to the relative proportion of functions. Md was mainly characterized by activities responsible for the degradation of organic material, particularly an increase in sulfate and selenate reducers and chitin degradation. Sulfur oxidizer was a shared function with M2. The microbiotype M2 was characterized by enhanced sulfur and methane metabolism, dehalogenation, and functions related to the degradation of various aromatic molecules (e.g., naphthalene and chlorophenol). The M1 and M3 microbiotypes both had an increase in processes involved in sulfur and nitrogen metabolism, and lignin and xylan degradation. The diversity of enhanced functions involved in nitrogen metabolism was higher in M3, while those involved in saccharide and polyphenol metabolism were higher in M1.

Taxonomy-based functional profiling of bacterial communities in giant clams (Tridacna maxima) by microbiotype. Enrichment (red) and decrease (blue) of functions are presented on a relative scale using a Pearson distance measure and the average clustering method. M, microbiotypes; Md, dying clam microbiotype; 1–3, clam microbiotype number

The Symbiodiniaceae composition of giant clams

The composition of the Symbiodiniaceae community was determined for 36 giant clam samples by Illumina sequencing of the ITS2 DNA region (49,318 ± 17,083 reads/sample, 1,775,437 sequence reads in total) and the 23S rRNA gene (86,541 ± 31,373 reads/sample, 3,115,502 sequences in total). After filtering, 1,209,269 ITS2 sequences were kept with a median length of 289 bp, representing 45,951 unique sequences, while 2,740,830 23S gene sequences were kept with a median length of 196 bp representing 29,420 unique sequences. The average number of ITS2 and 23S sequences per sample was 33,591 and 76,134, respectively.

The ITS2 marker identified Symbiodinium, Cladocopium, and Durusdinium, while the 23S marker detected Symbiodinium, Cladocopium, and Gerakladium in our giant clam samples (Additional file 6). With both markers, Symbiodinium was present in all 36 samples and was the dominant clade in all except two samples, where Cladocopium was the dominant algal genus. At a higher taxonomic resolution, we found two species of Symbiodinium with ITS2, A6, and A1, with A1 only found as the background species. Only one species in each of Cladocopium (C66) and Durusdinium (D17) were assigned in our samples. The 23S marker discriminated only one species in each of the algal genera present: A3, C3, and G9. Symbiodinium A6 (ITS2) and A3 (23S) were found in all samples. Cladocopium C3 (23S) co-occurred with Cladocopium C66 (ITS2) except for seven of 23 samples where only C66 was detected at low levels. Durusdinium D17 and Gerakladium G9 were detected in only 3 samples, AT1.L.1, AT1.S.1, and AT1.S.3, and T03.L.2, AT1.L.1, and AT1.S.3, respectively. Overall, Symbiodiniaceae composition did not correlate to any of the four microbiotypes or any experimental condition.

Discussion

Microbiomes, including viruses, bacteria, and fungi, are an integral part of multicellular organisms, contributing to their health and physiological performance. Despite a surge of interest in this research focus, very few invertebrate microbiomes have been studied, with the notable exception of insects. Among marine organisms, marine bivalves, especially oysters because of their economic value, are part of the few marine invertebrates of which microbial community has been studied [56,57,58,59]. In this study, we tested the influence of different benthic species assemblages on the microbial community and health of giant clams under two environmental contexts, by the concomitant analysis of the clams’ bacterial and algal microbiome. Hence, the current study has characterized for the first time the bacterial microbiome of T. maxima, from French Polynesia. The microbiome of giant clams is particularly interesting because clams are exposed to an extreme abundance and diversity of microbes through filter feeding, and because they live in symbiosis with dinoflagellate algae. We showed that the presence of the coral Acropora cytherea in an assemblage negatively affects the health of the giant clam Tridacna maxima and that this effect is amplified under temperature stress. Our results showed that nearly all clams with compromised health were characterized by a distinct microbiome in which the Vibrionaceae family was enriched. Interestingly, the bacterial community of healthy clams fell in three clusters irrespective of the composition of the benthic assemblage, the clams’ symbiotic algal composition, or water temperature. Our discovery of specific microbiome structure, detectable from the genus level, is the first description of microbiotypes in invertebrates.

The composition of benthic species assemblages influences the health of giant clams

The first remarkable result of this work is that the frequency of clam mortality, associated with a Vibrio infection, is correlated with the benthic species that surrounded them. When A. cytherea was present in the assemblage (PAT and AT), clam mortality increased. This pattern was particularly striking for PAT under increased temperature. Since all aquariums were filled with seawater from the same pipe and some healthy giant clams in T assemblages harbored the Vibrionaceae species at a lower proportion, the prevalent hypothesis is an increased susceptibility of infection due to the presence of corals. Benthic species, particularly corals, are highly competitive [60] and have been classified based on their aggressiveness [61,62,63,64]. Corals compete either by direct physical contact or via the production and secretion of secondary metabolites that can weaken or kill neighboring organisms [65,66,67,68,69,70]. These metabolites are produced by the coral host itself or by their associated microorganisms, some of which are known to synthetize toxic compounds [67, 71]. Other than the direct effect of a toxic metabolite potentially produced by A. cytherea or by its associated organisms, the decline and subsequent death of giant clams could also be the consequence of anti-inflammatory molecules produced by corals [72, 73], reducing the immune response of clams against microbial pathogens. An immune depression associated with the reproductive period and/or increase of water temperature has also been linked to vibriosis in poikilotherm organisms, including mollusks [74,75,76,77]. Few marine studies have recorded Catenococcus spp. [78,79,80]. However, this member of the Vibrionaceae family is described as a pathogen in the seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii in which infection by Catenococcus thiocyli causes bleaching [79]. Bacterial extracts from sponge Stylotella sp. of Proteobacteria closely related to Catenococcus thiocycli, showed toxicity activity [80]. As nearly all dying clams harbored a typical microbiome mainly composed of Vibrionaceae (Catenococcus spp. or an unclassified genus), we hypothesize that the combined effect of secondary metabolites from Acropora corals and increased water temperature may have weakened the clams’ defenses against Vibrio infection. Interestingly, the microbiome of two healthy clams, from T assemblage under thermal stress, showed similarities to that of dying clams. The relative proportion of Vibrionaceae in these two clams is higher than in other members of their microbiotype (11–15% of total bacterial families, compared with < 3% in other healthy clams and 25–50% in the majority of dying clams), suggesting that these clams might have had a compromised health without visible symptoms yet. Our results suggest that the relative proportion of Vibrionaceae could be used as an early indicator of clam health in natural populations.

Microbiotypes in giant clams

We used multiple genetic markers for profiling the Symbiodiniaceae diversity in giant clams, the advantages of which have recently been highlighted by Pochon et al. [12]. As expected, using both ITS2 and 23S markers, we found a higher level of taxonomic diversity, including the detection of free-living Symbiodiniaceae species in clam samples. Indeed, beyond the identification of Symbiodinium and Cladocopium species, ITS2 and 23S allowed for the detection of Durusdinium and Gerakladium species in some of our samples. In accordance with Pochon et al. [12], Symbiodinium tridacnidorum ([81]; former subclade A6/A3) was the dominant species in all but two of 36 samples. In these remaining two samples, subclade C66/C3 of Cladocopium species was dominant. Interestingly, Durusdinium was detected in our young giant clam samples while not detected before in adult clams from French Polynesia supporting the hypothesis that this algal genus is restricted to juvenile clams [11, 82]. Importantly, the composition of the clam Symbiodiniaceae community did not show any correlation with the composition of the experimental benthic assemblages, nor to thermal condition or to a particular microbiotype. Similarly, microbiome analysis did not highlight any link with species assemblages or thermal status. The major bacterial phyla found in the microbiome of T. maxima are those commonly found in marine invertebrates. Among them are Proteobacteria that assist in food digestion in bivalves and contribute to the host’s nitrogen uptake [83] and Bacteroidetes that play an important role in bivalve immunity by limiting the establishment of potentially pathogenic bacterial species [84]. The most abundant class was Gammaproteobacteria, and the most abundant families were Moraxellaceae and Rhodobacteraceae. Representatives of these families are present in the marine environment and some of them are described as symbionts of aquatic organisms such as certain bacteria of the Rhodobacteraceae family [59]. Interestingly, similarly to human enterotypes [85], T. maxima individuals harbored distinct microbiotypes (M1–M3). All three microbiotypes found in this study were clearly defined by their bacterial community composition. This variability in bacterial community composition could result from multiple inter-organismal interactions such as host-specific immune capacity allowing the presence or absence of bacteria incompatible with the presence of other bacterial genera [86,87,88,89]. These differences in microbial community composition, together with the systematic co-occurrence of certain bacterial taxa, create distinct functional biomarkers to the clam host. Thus, microbiotypes can use different pathways to achieve similar overall functions. For example, sulfur metabolism mostly involved sulfur reduction and sulfide oxidizing in M3, sulfide oxidizing in M1, and sulfur oxidizing, as well as an undetailed sulfur metabolic pathway in M2. Some of the most enriched functions were also specific to a given microbiotype, thus providing to its host-metabolic capacities. For example, M1 and M3 were mostly characterized by lignin and xylan degradation with an emphasis on cellulose degradation in M1. The most characteristic functions in M2 are related to pollutant degradation (aromatic compounds such as naphthalene or chlorophenol). We found all three microbiotypes in every experimental benthic assemblage, under both control and increased temperature, and in samples issued from the two different cohorts, suggesting that similarly to humans, microbiotypes are not driven by the environment or genetic factors. In fact, we found that at least three microbiotypes could exist in two distinct cohorts of clams collected in the same lagoon. This suggests that different microbiotypes can most likely confer similar functions to host organisms that allow them to thrive in the same environment. Metabolic pathways linked to microbiotypes presumably confer some specific functional properties to their clam host, and therefore will likely influence the adaptive capacity of clam populations to environmental change. Importantly, even though there was no change in the bacterial community during our thermal stress experiment, our results do not rule out that a more intense thermal stress would influence the composition of the Tridacna maxima microbiome, similarly to sponges (e.g., [90, 91]) and oysters [92].

Our work suggests that the diversity of species assemblages and thus the composition of the coral reef benthos, together with increasing water temperatures, could negatively impact the health of giant clams and potentially of other reef organisms. Our findings therefore support the idea that, similarly to terrestrial conservation and restoration, preserving entire benthic assemblages should be the goal of marine conservation strategies.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Four colonies of each of the two coral species, A. cytherea and P. damicornis, were collected in the Moorea lagoon, French Polynesia (Linareva site, 17° 30′ S, 149° 50′ W [93]), and fragmented in 45 nubbins each. As described in Guibert et al. [94], two cohorts of the giant clam T. maxima (cohort 1: 4-cm-long individuals, n = 150; cohort 2: 8-cm-long individuals, n = 70) were bought from a clam nursery (N° Tahiti: 139 519) on Reao Island (18° 28′ S, 136° 25′ W). The coral nubbins and giant clams were kept on underwater racks for 8 months in the Moorea lagoon, at the coral nursery ground of the InterContinental Moorea Resort & Spa. Each species was kept on a separate rack at 3 m depth below chart datum; the racks were separated by 3 m to minimize interspecific interactions during this acclimation period.

We constructed artificial benthic assemblages for thermal stress experiments composed of either one, two, or three species: P. damicornis + A. cytherea + T. maxima (PAT); A. cytherea + T. maxima (AT) and T. maxima alone (T) (Fig. 5). To set up the experiments, 12 specimens of each species of a given assemblage were used: three nubbins from each of four distinct colonies per coral species and 12 giant clam individuals. In addition, 3 additional clams were placed in T assemblages for each experiment (n = 9). Two open-circuit 40-L aquaria were set up per assemblage, with seawater pumped directly from Moorea’s Opunohu Bay at a flow rate of 20 L/h and filtered through two successive filters of 60 μm to remove sediments. After 12 days of acclimation (T0) at lagoon temperature (approximately 27 °C, L), one aquarium per assemblage was maintained at lagoon temperature while thermal stress (S) was applied to the second one. The temperature was increased by 1 °C per day until reaching 32 °C at day 17 (T1). The water temperature was controlled in each aquarium with the Biotherm pro system (Hobby, Stukenbrock, Germany). Temperature data were recorded every 10 min with temperature/light data loggers (P/N U22-001, Onset, Bourne, MA, or Ruskin, Ottawa, Canada). All aquaria received the same light using LED lamps (PlanetPro ELOS, Verona, Italy), following a diurnal cycle.

The 9 additional giant clams were sampled at day 12 (T0), and 28 individuals were sampled randomly at day 17 (T1). A small piece of the mantle was sampled and stored in 70 % ethanol at − 20 °C until molecular analysis. The remaining parts of the clams’ mantle were stored at − 80 °C for further studies. The experiments were performed twice for each benthic species assemblage, spaced 2 weeks apart, except for the AT assemblage which was also studied in duplicate but during the same experiment. For each of the experiments, the aquaria were randomly chosen to avoid a potential aquarium effect. The health of giant clams was monitored daily by visual observations (closure reactivity, color, mantle aspect), and mortalities were recorded.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing

Genomic DNA of giant clams from the main study were isolated following the bench protocol for animal tissues (DNEasy Blood and Tissue Kit, Qiagen) after rinsing the sample with sterile freshwater. Three different genetic markers were selected for metabarcoding. The bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene’s V3/V4 region was amplified with the “Bakt_341” forward (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′) and “Bakt_805” reverse (5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′) primers [95]. Symbiodiniaceae diversity was analyzed with two genetic markers. The internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) region of the nuclear ribosomal array was amplified with the “itsD” forward (5′-GTGAATTGCAGAACTCCGTG-3′) and “ITS2-Rev2” reverse (5′-GCCTCCGCTTACTTATATGCT-3′) primers [96]. The chloroplast cp23S-rDNA domain V region was amplified with the forward primer “23SHYPERUP” (5′-TCAGTACAAATAATATGCTG-3′) and the reverse primer “23SHYPERDN” (5′-GTTATCGCCCCAATTAAACAGT-3′) [97]. The primers were modified to include Illumina™ overhang adaptors as described by Kozich et al. [98].

Polymerase chain reactions were performed using 10 to 50 ng of template DNA in 50 μL volumes with the reaction mixture containing 5 μL GC enhancer, 1 μL of each primer (10 pmol/μL), and 30 μL AmpliTaq Gold® 360 PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). After a denaturing step of 3 min at 95 °C, 40 or 45 cycles consisting of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 52 °C, and 90 s at 72 °C were performed followed by a final elongation at 72 °C for 7 min. Amplicons were visualized on a 2% agarose gel. Samples were purified using magnetic beads (Agencourt Bioscience Corporation, Grand Rapids, Michigan), quantified (Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and diluted to 3 ng/μL concentration. Internal quality controls were used with two amplicons from DNA samples of Ciona savignyi and Asterias amurensis [99]. Nuclease-free UltraPure™ water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used as a negative control. The final HTS library preparation and paired-end run sequencing (MiSeq Illumina™ platform, 2 × 250 bp) were performed by New Zealand Genomics Ltd. at the University of Auckland. Sequencing failed for one sample (T02.L3; 781 reads), which was removed from the analysis.

Raw data are available on BioProject, no. PRJNA494911 (NCBI).

Microbial community analysis

Bacterial community analyses were performed using the MiSeq standard operating procedure (SOP) in MOTHUR (v1.39.5; http://www.mothur.org/) to produce operational taxonomic units (OTUs) [98]. Briefly, sequence reads were assembled into contigs and amplicon adaptors removed, then trimmed to improve quality (quality control ≥ 35) and split into two groups based on genetic markers (bacterial 16S and 23S). Unique sequences were selected and counted for bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Sequences were aligned to the SILVA full-length sequences and taxonomic references (Silva-vr128) using the K-mer search method [100]. The “screen.seqs” command was used to remove insertions or deletions, and the sequences were filtered to remove the overhangs at both ends. Unique sequences were selected again to eliminate the potential redundancy created during sequence trimming. A pre-cluster step (2-bp difference) was performed, and the VSEARCH algorithm was employed to remove chimeras [101]. The SILVA database was used to assign sequences with a cutoff level of 80, and mitochondria and chloroplast assignments were removed. Operational taxonomic units were then clustered under a 0.03 cutoff level and phylotypes were determined by taxonomic classification. Rarefaction curves were calculated using rarecurve function in the vegan R package v2.6-13 with a subsampling of 20 and 100 permutations.

To analyze the alpha diversity, samples were subsampled to 8911 sequences and then clustered into OTUs with a cutoff of ≤ 0.03. Chao1 and Inverse Simpson Indices were performed in MOTHUR [102,103,104]. To assess the putative functional profiles of the bacterial community of giant clams, METAGENassist [105] was used for automated taxon-to-phenotype mapping. During METAGENassist’s own data processing, data filtering was based on interquartile range [106] and variables with over 50% zeroes were removed. The 288 remaining variables (OTUs) were normalized over sample by sum and range scaling. Data were analyzed for “metabolism by phenotype” using a Pearson distance measure and an average clustering method to visualize the top 28 features in a heatmap.

The bacterial community analysis was also preformed according to a second approach: the gene content inference with a single-nucleotide resolution by using the dada2 version 1.12.1 [107] followed by the functional prediction with PICRUSt2 [108] from the dada2 ASV table. The scripts are described in Additional file 7.

Analysis of the Symbiodiniaceae community was adapted from Arif et al. [109]. Sequences were annotated via BLASTN using an ITS2 database [109] and a custom 23S database (Additional file 8) [110].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R v3.4.2 [111, 112]. For the bacterial correlation analysis, the raw counts per sample were homogenized to counts per million and centered. Pairwise correlation was performed with the Pearson method and clustered with the Ward method. The relative abundances of bacterial families were performed following Röthig et al. [113] and using Venny for determining the presence/absence of bacterial families (2.1.0, http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html). Statistical analysis of PICRUSt2 functional profiles was performed with STAMP [114]. The Symbiodiniaceae community composition was analyzed following the same workflow as for bacterial relative abundances. Data manipulation and visualization was done using the R packages (reshape2 and ggplot2). A logistic regression (logit) was performed on the giant clams’ health data.

Availability of data and materials

Supplemental information for this article can be found at Microbiome Journal. All data are available upon request. Raw data are available on BioProject, no. PRJNA494911 (NCBI)

References

Neo ML, Eckman W, Vicentuan K, Teo SLM, Todd PA. The ecological significance of giant clams in coral reef ecosystems. Biol Conserv. Elsevier Ltd. 2015;181:111–23. Available from:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.004.

Cabaitan PC, Gomez ED, Aliño PM. Effects of coral transplantation and giant clam restocking on the structure of fish communities on degraded patch reefs. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol. 2008;357:85–98.

Yonge CM. Giant clams. Sci Am. 1975;232:96–105.

Gosling E. Bivalve molluscs: biology, ecology and culture. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2015.

Klumpp DW, Griffith CL. Contributions of phototrophic and heterotrophic nutrition to the metabolic and growth requirements of four species of giant clam (Tridacnidae). Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1994;115:103–16.

Trench RK, Wethey DS, Porter JW. Observation on the symbiosis with zooxanthellae among the Tridacnidae (Mollusca, Bivalvia). Biol Bull. 1981;161:180–93.

Fitt WK, Trench RK. Spawning, development, and acquisition of zooxanthellae by Tridacna squamosa (mollusca, bivalvia). Biol Bull. 1981;135:141–8.

Pochon X, Gates RD. A new Symbiodinium clade (Dinophyceae) from soritid foraminifera in Hawai’i. Mol Phylogenet Evol. Elsevier Inc.; 2010;56:492–7. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20371383. [cited 2014 May 8].

LaJeunesse TC, Parkinson JE, Gabrielson PW, Jeong HJ, Reimer JD, Voolstra CR, et al. Systematic revision of Symbiodiniaceae highlights the antiquity and diversity of coral endosymbionts. Curr Biol. Elsevier Ltd.; 2018;28:1–11. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960982218309072.

DeBoer T, Baker A, Erdmann M, Jones P, Barber P. Patterns of Symbiodinium distribution in three giant clam species across the biodiverse Bird’s Head region of Indonesia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2012;444:117–32. Available from: http://apps.webofknowledge.com.gate1.inist.fr/full_record.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=21&SID=W2OMk5@17j8GED2o3gI&page=1&doc=6&cacheurlFromRightClick=no.

Ikeda S, Yamashita H, Kondo S, Inoue K, Morishima S, Koike K. Zooxanthellal genetic varieties in giant clams are partially determined by species-intrinsic and growth-related characteristics. Todd PA, editor. PLoS One. Public Library of Science; 2017;12:e0172285. Available from:http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172285.

Pochon X, Wecker P, Stat M, Berteaux-Lecellier V, Lecellier G. Towards an in-depth characterization of Symbiodiniaceae in tropical giant clams via metabarcoding of pooled multi-gene amplicons. PeerJ. 2019;7:e6898.

Pochon X, Putnam HM, Gates RD. Multi-gene analysis of Symbiodinium dinoflagellates: a perspective on rarity, symbiosis, and evolution. PeerJ. 2014;2:e394. Available from:http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4034598&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Pochon X, LaJeunesse TC, Pawlowski J. Biogeographic partitioning and host specialization among foraminiferan dinoflagellate symbionts (Symbiodinium; Dinophyta). Mar Biol. 2004;146:17–27.

Baillie BK, Belda-Baillie CA, Maruyama T. Conspecificity and Indo-Pacific distribution of Symbiodinium genotypes (dinophyceae) from giant clams. J Phycol. 2000;36:1153–61.

Pappas MK, He S, Hardenstine RS, Kanee H, Berumen ML. Genetic diversity of giant clams (Tridacna spp.) and their associated Symbiodinium in the central Red Sea. Mar Biodivers. Marine Biodiversity. 2017;47:1209–22.

Buck BH, Rosenthal H, Ulrich S-P. Effect of increased irradiance and thermal stress on the symbiosis of Symbiodinium microadriaticum and Tridacna gigas. Aquat Living Resour. 2002;15:107–17.

Leggat W, Buck BH, Grice A, Yellowlees D. The impact of bleaching on the metabolic contribution of dinoflagellate symbionts to their giant clam host. Plant, Cell Environ. 2003;26:1951–61.

Dubousquet V. Diversité génétique du bénitier (Tridacna maxima) en Polynésie française et réponse au stress thermique: une approche intégrée de génomique fonctionnelle. Thesis Université de la Polynésie française 2014. p. 1-293. Available from: http://www.theses.fr/s76855.

Dubousquet V, Gros E, Berteaux-Lecellier V, Viguier B, Raharivelomanana P, Bertrand C, et al. Changes in fatty acid composition in the giant clam Tridacna maxima in response to thermal stress. Biol Open. 2016;5:1400–7. Available from:http://bio.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/bio.017921.

Adessi L. Giant clam bleaching in the lagoon of Takapoto atoll (French Polynesia). Coral reefs. 2001;19:220.

Andréfouët S, Van Wynsberge S, Gaertner-Mazouni N, Menkes C, Gilbert A, Remoissenet G. Climate variability and massive mortalities challenge giant clam conservation and management efforts in French Polynesia atolls. Biol Conserv. 2013;160:190–9.

Berkelmans R, van Oppen MJH. The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a “nugget of hope” for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2006;273:2305–12.

Cooper TF, Berkelmans R, Ulstrup KE, Weeks S, Radford B, Jones AM, et al. Environmental factors controlling the distribution of Symbiodinium harboured by the coral Acropora millepora on the great barrier reef. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–13.

Cunning R, Yost DM, Guarinello ML, Putnam HM, Gates RD. Variability of Symbiodinium communities in waters, sediments, and corals of thermally distinct reef pools in American Samoa. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–17. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145099.

Silverstein RN, Cunning R, Baker AC. Change in algal symbiont communities after bleaching, not prior heat exposure, increases heat tolerance of reef corals. Glob Chang Biol. 2015;21:236–49.

Little AF, Oppen MJH van, Willis BL. Flexibility in algal endosymbioses shapes growth in reef corals. Science. 2004;304:1492–5.

Coffroth MA, Poland DM, Petrou EL, Brazeau DA, Holmberg JC. Environmental symbiont acquisition may not be the solution to warming seas for reef-building corals. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–7.

Rosenberg E, Koren O, Reshef L, Efrony R, Zilber-Rosenberg I. The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:355–62.

Bourne DG, Morrow KM, Webster NS. Insights into the coral microbiome: underpinning the health and resilience of reef ecosystems. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2016;70:317–40. Available from:http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-micro-102215-095440.

Welsh RM, Rosales SM, Zaneveld JR, Payet JP, McMinds R, Hubbs SL, et al. Alien vs. predator: bacterial challenge alters coral microbiomes unless controlled by Halobacteriovorax predators. PeerJ. 2017;5:2–22. Available from:https://peerj.com/articles/3315.

Al-Dahash LM, Mahmoud HM. Harboring oil-degrading bacteria: a potential mechanism of adaptation and survival in corals inhabiting oil-contaminated reefs. Mar Pollut Bull. Elsevier Ltd. 2013;72:364–74. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.08.029.

Bourne D, Iida Y, Uthicke S, Smith-keune C. Changes in coral-associated microbial communities during a bleaching event. ISME J. 2008;2:350–63.

Thurber RV, Willner-Hall D, Rodriguez-Mueller B, Desnues C, Edwards RA, Angly F, et al. Metagenomic analysis of stressed coral holobionts. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2148–63.

Ziegler M, Roik A, Porter A, Zubier K, Mudarris MS, Ormond R, et al. Coral microbial community dynamics in response to anthropogenic impacts near a major city in the central Red Sea. MPB. The Authors. 2016;105:629–40. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.12.045.

Ziegler M, Seneca FO, Yum LK, Palumbi SR, Voolstra CR. Bacterial community dynamics are linked to patterns of coral heat tolerance. Nat Commun. Nature Publishing Group. 2017;8:1–8. Available from:https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14213.

Hadaidi G, Röthig T, Yum LK, Ziegler M, Arif C, Roder C, et al. Stable mucus-associated bacterial communities in bleached and healthy corals of Porites lobata from the Arabian Seas. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group. 2017;7:1–11. Available from:https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45362.

Epstein HE, Smith HA, Torda G, van Oppen MJH. Microbiome engineering: enhancing climate resilience in corals. Front Ecol Environ. 2019:1–9.

Rosenberg E. Ben-haim Y. Microbial diseases of corals and global warming. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:318–26.

Rouzé H, Lecellier G, Saulnier D, Berteaux-Lecellier V. Symbiodinium clades A and D differentially predispose Acropora cytherea to disease and Vibrio spp. colonization. Ecol Evol. 2016;1–23. Available from:http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ece3.1895.

Sharp KH, Pratte ZA, Kerwin AH, Rotjan RD, Stewart FJ. Season, but not symbiont state, drives microbiome structure in the temperate coral Astrangia poculata. Microbiome. 2017;5:120. Available from:http://microbiomejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40168-017-0329-8.

Wegley L, Edwards R, Rodriguez-Brito B, Liu H, Rohwer F. Metagenomic analysis of the microbial community associated with the coral Porites astreoides. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2707–19.

Gosling E. Marine bivalve molluscs. Sons JW &, editor. 2015. Available from: https://books.google.fr/books?id=9YRxBgAAQBAJ&lpg=PA243&ots=uQqTq2uy8Y&dq=gosling2015bivalve&lr&hl=fr&pg=PA4#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Zannella C, Mosca F, Mariani F, Franci G, Folliero V, Galdiero M, et al. Microbial diseases of bivalve mollusks: infections, immunology and antimicrobial defense. Mar Drugs. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2017;15:1–36. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28629124.

Travers MA, Mersni Achour R, Haffner P, Tourbiez D, Cassone AL, Morga B, et al. First description of French V. tubiashii strains pathogenic to mollusk: I. Characterization of isolates and detection during mortality events. J Invertebr Pathol. 2014;123:38–48.

Le Guyader FS, Bon F, DeMedici D, Parnaudeau S, Bertone A, Crudeli S, et al. Detection of multiple noroviruses associated with an international gastroenteritis outbreak linked to oyster consumption. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3878–82.

Kaas L, Ogorzaly L, Lecellier G, Berteaux-Lecellier V, Cauchie H, Langlet J. Detection of human enteric viruses in french polynesian wastewaters, environmental waters and giant clams. Food Environ Virol. 2018;1–13. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12560-018-9358-0.

Rossbach S, Cardenas A, Perna G, Duarte CM, Voolstra CR. Tissue-specific microbiomes of the Red Sea giant clam Tridacna maxima highlight differential abundance of Endozoicomonadaceae. Front Microbiol. 2019;10.

Jameson SC. Early life history of the giant clams Tridacna crocea (Lamarck), Tridacna maxima (Reding), and Hippopus hippopus (Linnaeus). Pacific Sci. 1976;30:219–33. Available from:https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10125/10783.

Ainsworth TD, Krause L, Bridge T, Torda G, Raina J-B, Zakrzewski M, et al. The coral core microbiome identifies rare bacterial taxa as ubiquitous endosymbionts. ISME J. 2015;9:2261–74. Available from:http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/ismej.2015.39.

Leite DCA, Leão P, Garrido AG, Lins U, Santos HF, Pires DO, et al. Broadcast spawning coral Mussismilia Hispida can vertically transfer its associated bacterial core. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–12.

Leite DCA, Salles JF, Calderon EN, Castro CB, Bianchini A, Marques JA, et al. Coral bacterial-core abundance and network complexity as proxies for anthropogenic pollution. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1–11.

Wecker P, Fournier A, Bosserelle P, Debitus C, Lecellier G, Berteaux-Lecellier V. Dinoflagellate diversity among nudibranchs and sponges from French Polynesia: insights into associations and transfer. Comptes Rendus - Biol. 2015;338:278–83.

Greff S, Aires T, Serrão EA, Engelen AH, Thomas OP, Pérez T. The interaction between the proliferating macroalga Asparagopsis taxiformis and the coral Astroides calycularis induces changes in microbiome and metabolomic fingerprints. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group. 2017;7:1–14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42625.

Zaneveld JR, Burkepile DE, Shantz AA, Pritchard CE, McMinds R, Payet JP, et al. Overfishing and nutrient pollution interact with temperature to disrupt coral reefs down to microbial scales. Nat Commun. 2016;7:1–12.

Pierce ML, Ward JE. Microbial ecology of the Bivalvia, with an emphasis on the family Ostreidae. J Shellfish Res. 2018;37:793–806. Available from:http://www.bioone.org/doi/10.2983/035.037.0410.

Khan B, Clinton SM, Hamp TJ, Oliver JD, Ringwood AH. Potential impacts of hypoxia and a warming ocean on oyster microbiomes. Mar Environ Res. Elsevier Ltd; 2018;139:27–34. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2018.04.018.

Clerissi C, Lorgeril J de, Petton B, Lucasson A, Escoubas J-M, Gueguen Y, et al. Diversity and stability of microbiota are key factors associated to healthy and diseased Crassostrea gigas oysters. bioRxiv. 2018;1–30. Available from:https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/07/26/378125.

Milan M, Carraro L, Fariselli P, Martino ME, Cavalieri D, Vitali F, et al. Microbiota and environmental stress: how pollution affects microbial communities in Manila clams. Aquat Toxicol. 2018;194:195–207.

Figuerola B, Núñez-pons L, Vázquez J, Taboada S, Cristobo J, Ballesteros M, et al. Chemical interactions in Antarctic marine benthic ecosystems. Mar Ecosyst. 2011;105–26. Available from: www.intechopen.com.

Abelson A, Loya Y. Interspecific aggression among stony corals in eilat, Red Sea: a hierarchy of aggression ability and related parameters. Bull Mar Sci. 1999;65:851–60.

Horwitz R, Hoogenboom MO, Fine M. Spatial competition dynamics between reef corals under ocean acidification. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group. 2017;7:1–13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep40288.

Álvarez-Noriega M, Baird AH, Dornelas M, Madin JS, Connolly SR. Negligible effect of competition on coral colony growth. Ecology. 2018;99:1347–56.

Lang JC, Chornesky E. Competition between scleractinian reef corals - a review of mechanisms and effects. In: Dubinsky, editor. Coral reefs. 1990. p. 209–52.

Wang CY, Liu HY, Shao CL, Wang YN, Li L, Guan HS. Chemical defensive substances of soft corals and Gorgonians. Acta Ecol Sin. 2008;28:2320–8.

Gao C, Yi X, Huang R, Yan F, He B, Chen B. Alkaloids from corals. Chem Biodivers. 2013;10:1435–47.

Puglisi MP, Sneed JM, Sharp KH, Ritson-Williams R, Paul VJ. Marine chemical ecology in benthic environments. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1510–53.

Pochon X, Garcia-Cuetos L, Baker AC, Castella E, Pawlowski J. One-year survey of a single Micronesian reef reveals extraordinarily rich diversity of Symbiodinium types in soritid foraminifera. Coral Reefs. 2007;26:867–82.

Ben-Ari H, Paz M, Sher D. The chemical armament of reef-building corals: inter- and intra-specific variation and the identification of an unusual actinoporin in Stylophora pistilata. Sci Rep. Springer US. 2018;8:1–13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-18355-1.

Garcia-Arredondo A, Rojas-Molina A, Ibarra-Alvarado C, Lazcano-Perez F, Arreguin-Espinosa R, Sanchez-Rodriguez J. Composition and biological activities of the aqueous extracts of three scleractinian corals from the Mexican Caribbean: Pseudodiploria strigosa, Porites astreoides and Siderastrea siderea. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases; 2016;22:1–14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40409-016-0087-2.

Leal MC, Calado R, Sheridan C, Alimonti A, Osinga R. Coral aquaculture to support drug discovery. Trends Biotechnol. 2013:1–7.

Khalesi MK. Corals. Mar Flora Fauna. 2012. p. 179–217.

Cooper EL, Hirabayashi K, Strychar KB, Sammarco PW. Corals and their potential applications to integrative medicine. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2014:1–10.

Travers MAS, Basuyaux O, Le Goïc N, Huchette S, Nicolas JL, Koken M, et al. Influence of temperature and spawning effort on Haliotis tuberculata mortalities caused by Vibrio harveyi: an example of emerging vibriosis linked to global warming. Glob Chang Biol. 2009;15:1365–76.

Travers MA, Le Goïc N, Huchette S, Koken M, Paillard C. Summer immune depression associated with increased susceptibility of the European abalone, Haliotis tuberculata to Vibrio harveyi infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;25:800–8.

Matozzo V, Marin M. Bivlave immune response and climate changes: is there a relationship? Invertebr Surviv J. 2011;8:70–7.

Hooper C, Day R, Slocombe R, Benkendorff K, Handlinger J, Goulias J. Effects of severe heat stress on immune function, biochemistry and histopathology in farmed Australian abalone (hybrid Haliotis laevigata × Haliotis rubra). Aquaculture. Elsevier B.V.; 2014;432:26–37. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.03.032.

Achmad M, Alimuddin A, Widyastuti U, Sukenda S, Suryanti E, Harris E. Molecular identification of new bacterial causative agent of ice-ice disease on seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii. PeerJ Prepr. 2016;4:1–21. Available from. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2016v1.

Zheng Y, Yu M, Liu Y, Su Y, Xu T, Yu M, et al. Comparison of cultivable bacterial communities associated with Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) larvae at different health statuses and growth stages. Aquaculture. Elsevier B.V.; 2016;451:163–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.09.020.

Yoghiapiscessa D, Batubara I, Wahyudi AT. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of bacterial extracts from marine bacteria associated with sponge Stylotella sp. Am J Biochem Biotechnol. 2016;12:36–46.

Lee SY, Jeong HJ, Kang NS, Jang TY, Jang SH, Lajeunesse TC. Symbiodinium tridacnidorum sp. nov., a dinoflagellate common to Indo-Pacific giant clams, and a revised morphological description of Symbiodinium microadriaticum Freudenthal, emended Trench & Blank. Eur J Phycol. Taylor & Francis; 2015;50:155–172. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/09670262.2015.1018336.

Weber M. The biogeography and evolution of Symbiodinium in giant clams (Tridacnidae). 2009.

Harris JM. The presence, nature, and role of gut microflora in aquatic invertebrates: a synthesis. Microb Ecol. 1993;25:195–231.

Leite L, Jude-Lemeilleur F, Raymond N, Henriques I, Garabetian F, Alves A. Phylogenetic diversity and functional characterization of the Manila clam microbiota: a culture-based approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2017;24:21721–32.

Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Batto J, Bertalan M, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2013;473:174–80.

Wippler J, Kleiner M, Lott C, Gruhl A, Abraham PE, Giannone RJ, et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic insights into innate immunity and adaptations to a symbiotic lifestyle in the gutless marine worm Olavius algarvensis. BMC Genomics. 2016;17:1–19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-016-3293-y.

Chu H, Mazmanian SK. Innate immune recognition of the microbiota promotes host- microbial symbiosis. Nat Immunol. 2014;14:668–75.

Qian PY, Lau SCK, Dahms HU, Dobretsov S, Harder T. Marine biofilms as mediators of colonization by marine macroorganisms: implications for antifouling and aquaculture. Mar Biotechnol. 2007;9:399–410.

Dobretsov S, Teplitski M, Paul V. Mini-review: quorum sensing in the marine environment and its relationship to biofouling. Biofouling. 2009;25:413–27.

Erwin PM, Pita L, López-Legentil S, Turon X. Stability of sponge-bacteria symbioses over large seasonal shifts in temperature and irradiance. Invertebr Microbiol. 2013:1–44.

Simister R, Taylor MW, Tsai P, Fan L, Bruxner TJ, Crowe ML, et al. Thermal stress responses in the bacterial biosphere of the great barrier reef sponge. Rhopaloeides odorabile. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:3232–46.

Lokmer A, Mathias WK. Hemolymph microbiome of Pacific oysters in response to temperature, temperature stress and infection. ISME J. Nature Publishing Group. 2015;9:670–82. Available from:https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.160.

Rouzé H, Lecellier G, Langlade M, Planes S, Berteaux-Lecellier V. Fringing reefs exposed to different levels of eutrophication and sedimentation can support the same benthic communities. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015;92:212–21.

Guibert I, Bonnard I, Pochon X, Zubia M, Sidobre C, Lecellier G, et al. Differential effects of coral-giant clam assemblages on biofouling formation. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–12.

Marcelino VR, Verbruggen H. Multi-marker metabarcoding of coral skeletons reveals a rich microbiome and diverse evolutionary origins of endolithic algae. Sci Rep. Nature Publishing Group; 2016;1–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31508.

Pochon X, Stat M, Takabayashi M, Chasqui L, Chauka LJ, Logan DDK, et al. Comparison of endosymbiotic and free-living Symbiodinium (dinophyceae) diversity in a Hawaiian reef environment. J Phycol. 2010;46:53–65.

Manning MM, Gates RD. Diversity in populations of free-living Symbiodinium from a Caribbean and Pacific reef. Limnol Oceanogr. 2008;53:1853–61.

Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–20.

Pochon X, Bott NJ, Smith KF, Wood SA. Evaluating detection limits of next-generation sequencing for the surveillance and monitoring of international marine pests. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–12.

Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7188–96.

Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016;4:2584. Available from: https://peerj.com/articles/2584.

Simpson EH. Measurement of diversity. Nature. 1949. p. 688.

Chao A. Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand J Stat. 1984;11:265–70.

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–41.

Arndt D, Xia J, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Guo AC, Cruz JA, et al. METAGENassist: a comprehensive web server for comparative metagenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:88–95.

Hackstadt AJ, Hess AM. Filtering for increased power for microarray data analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:11. Available from:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/10/11.

Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–3.

Douglas GM, Maffei VJ, Zaneveld J, Yurgel SN, Brown JR, Taylor CM, et al. PICRUSt2: an improved and extensible approach for metagenome inference. bioRxiv. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 2019;672295.

Arif C, Daniels C, Bayer T, Banguera-Hinestroza E, Barbrook A, Howe CJ, et al. Assessing Symbiodinium diversity in scleractinian corals via next-generation sequencing-based genotyping of the ITS2 rDNA region. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:4418–33.

Takabayashi M, Adams LM, Pochon X, Gates RD. Genetic diversity of free-living Symbiodinium in surface water and sediment of Hawai’i and Florida. Coral Reefs. 2012;31:157–67.

R core team. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for statistical computing; 2014.

Oliveros JV. An interactive tool for comparing lists with Venn’s diagrams. 2015. Available from:http://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html.

Röthig T, Roik A, Yum LK, Voolstra CR. Distinct bacterial microbiomes associate with the deep-sea coral Eguchipsammia Fistula from the Red Sea and from aquaria settings. Front Mar Sci. 2017;4:1–12. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmars.2017.00259/full.

Parks DH, Tyson GW, Hugenholtz P, Beiko RG. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics. 2014.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Academie française for their financial support through the Walter-Zellidja Grant and the Cawthrown Institute, New Zealand, for hosting IG to conduct the metabarcoding analyses. We acknowledge the InterContinental Resort & Spa Moorea and the Moorea Dolphin Center for providing coral garden protected area. We also thank Franck Lerouvreur, Pascal Ung, Ewen Morin, and students from CRIOBE who helped with the fieldwork.

Funding

This work was supported by LabexCorail and CNRS fundings. IG was a fellow of Sorbonne University–Doctoral school 129.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IG, VB, and GL conceived and designed the experiments. IG and VB performed the experiments. IG and XP generated the data. IG, VB, and GL analyzed the data. IG, VB, GL, GT, and XP discussed the results and wrote the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IUCN Red List Status of giant clams Tridacna maxima is Lower Risk: conservation dependent (LR/cd). A CITES permit was obtained to allow for samples export (CITES – FR1698700087 – E).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Numbering of remaining giant clams in the aquariums during the acclimation period and experimental period according to health status. d0: seeding in the aquarium, Alive: number of healthy giant clams, Death= number of dying giant clams, Pred: death by predation. PAT: P. damicornis, A. cytherea and T. maxima; AT: A. cytherea and T. maxima; T: T. maxima; L: lagoon temperature; S: thermal stress.

Additional file 2.

Metabarcoding results of bacteria. PAT: P. damicornis, A. cytherea and T. maxima; AT: A. cytherea and T. maxima; T: T. maxima; 0: control; (1-3): experiment number; L: lagoon temperature; S: thermal stress; (1-4): sample number.

Additional file 3.

Rarefaction curves of sequences from the different microbiotypes (Md, M1, M2 and M3).

Additional file 4.

Summary statistics of 16s DNA-based bacterial community composition of giant clams according to their groups. Based on subsampled sequences (n=8,411). G: groups; AVG: average; SD: standard deviation; PAT: P. damicornis, A. cytherea and T. maxima; AT: A. cytherea and T. maxima; T: T. maxima; 0: control; (1-3): experiment number; L: lagoon temperature; S: thermal stress; (1-4): sample number.

Additional file 5.

Principal Component Analysis build from PICRUSt2 analysis on the bacterial communities of T. maxima according to the microbiotypes. M: microbiotypes, Md: dying clam microbiotype; 1-3: clam microbiotype number.

Additional file 6.

Relative abundance of Symbiodiniaceae subclades in Tridacna maxima determined by Illumina sequencing of the ITS2 DNA region (a) and the 23S rRNA gene (b). Abbreviations of experimental assemblages: PAT: P. damicornis, A. cytherea and T. maxima; AT: A. cytherea and T. maxima; T: T. maxima; 0: control; (1-3): experiment number; L: lagoon temperature; S: thermal stress; (1-4): sample number.

Additional file 7.

Script of the bacterial community analysis performed with dada2.

Additional file 8.

23s custom database.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guibert, I., Lecellier, G., Torda, G. et al. Metabarcoding reveals distinct microbiotypes in the giant clam Tridacna maxima. Microbiome 8, 57 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00835-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-020-00835-8