Abstract

Background

Disruptive behaviours are a recurrent concern in online gaming and are usually dealt with through reactive and punitive strategies. However, in health and educational settings, workplaces, and the context of interpersonal relationships, positive behaviour interventions have been implemented as well. This systematic review assessed the use of positive behaviour strategies as well as their effectiveness in a range of environments to suggest routes for transferring such interventions to (multiplayer) online gaming.

Methods

We included 22 records in the review and examined (a) the targeted individuals/groups, (b) the specific disruptive behaviour problems that were addressed, (c) the nature of the positive behaviour strategy intervention, and (d) its effectiveness.

Results

Findings showed that the most common interventions that have been investigated thus far are the promotion of active bystander intervention, the good behaviour game, and tootling/positive peer reporting. These sought to prevent or reduce aggressive behaviour, negative peer interaction, name-calling, cyberbullying, and hate speech. The identified interventions differed in their effectiveness; however, all demonstrated some degree of positive impact.

Conclusions

Considering similarities and differences between online and offline settings, we propose that tootling and the good behaviour game are most suitable to be applied to (multiplayer) online gaming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Toxic and disruptive behaviour, for example, harassment, insults, and abuse (Kordyaka et al., 2019, 2020; Hilvert-Bruce & Neill, 2020; Nash et al., 2015; Villafranca et al., 2017) is prevalent in health and educational environments (Castello, 2018; Chaffee et al., 2020; Fazackerley, 2023; Moreiraa et al., 2019; Narhia et al., 2017), workplaces (Bowen et al., 2011; Kordyaka et al., 2020; Rogers-Clark et al., 2009), in interpersonal relationships (Akhter et al., 2020), as well as on social media platforms, in online forums, and online gaming (Marsh, 2023).Footnote 1 In the latter setting, the focus of this research, disruptive behaviour is defined as conduct that infringes community standards, causes distress, persists in causing harm after it occurs, and disturbs an entire community (Blackburn & Kwak, 2014).

According to a recent study, 80 per cent of players agreed that the typical gamer encounters disruptive behaviour online (Cary et al., 2020). More than half of male and female players reported having experienced abuse while playing, with nearly 28 per cent noting the regular occurrence of abuse (Bryter, 2020). Rubin et al. (2020) further noted that disruptive behaviour is not only unsettling to players while they are online but also impacts their ‘offline lives’. Specifically, in a report from the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) (2019), 23 per cent of participants expressed that disruptive behaviour made them less social and uncomfortable/upset after playing; 14 per cent felt isolated and alone; 10 per cent had depressive/suicidal thoughts; 9 per cent treated people worse than usual after experiencing incidents of disruptive behaviour; and 8 per cent had personal relationships disrupted and feared for their physical safety (ADL, 2019). Overall, the high risk of exposure to disruptive behaviour in online gaming environments has serious implications for players’ well-being (Kowert & Cook, 2022).

The common approaches to addressing disruptive behaviour in online gaming are punitive and reactive measures (Beres et al., 2021; Kordyaka et al., 2022; Märtens et al., 2015; Reid et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2020). More precisely, in most games, players can be reported for displaying negative attitudes (griefing or giving up), verbal abuse (harassment or offensive language), leaving the game/being away from the keyboard (AFK), intentional feeding (feeding is griefing, not just having a bad game), hate speech (racism, sexism, homophobia, etc.), or cheating (using unapproved third-party programs). After a player is reported, the overall frequency and quality of (previous) reports are considered, and a potential punishment is determined. A player can face different outcomes, the most common being chat restrictions, temporary bans, temporary in-game restrictions, or permanent bans (Kou, 2021).

Unfortunately, there is growing evidence to suggest that these punitive countermeasures are not effective (ADL, 2019; Blackburn & Kwak, 2014; Kou, 2021; Monge & O'Brien, 2022; Pohjanen, 2018). It is, therefore, crucial that additional interventions to prevent or attenuate incidents of disruptive behaviour in online gaming are developed. The gaming industry acknowledges these concerns as well. After all, disruptive behaviour also poses a threat to their profit; individuals may avoid playing online games if disruptive behaviour persists (Beres et al., 2021). Game companies, such as Riot Games, Blizzard Entertainment, Electronic Arts, and Epic Games, as well as gaming-adjacent platforms such as Twitch, Discord, and Facebook gaming, have formed the Fair Play Alliance coalition (Beres et al., 2021; Free Pay Alliance, 2021). The objective of this partnership is to provide opportunities for experts and companies to create and share best practices to encourage ‘healthy’ online gaming communities and positive experiences for players (Free Pay Alliance, 2021). Nonetheless, to date, the Fair Play Alliance has not introduced any new approaches to deal with disruptive behaviour. Importantly, previous research has also failed to address this issue (Poeller et al., 2023).

We argue that positive behaviour interventions, such as active bystander intervention or tootling, which have been implemented across a variety of different settings (Abdelmonem, 2022; Chaffee et al., 2020; Haydon et al., 2022; Lodge & Frydenberg, 2005; Macaulay et al., 2022), are suitable to complement punitive and reactive measures to improve players’ behaviour. However, to make concrete recommendations about the application of positive behaviour strategies to the context of online gaming requires insights that have, thus far, not been collated. The present study aims to address this gap. Specifically, we aim to synthesise the literature on (a) the application of different positive behaviour interventions in various contexts as well as (b) their respective effectiveness in a systematic review to then propose which of the strategies could or should be transferred to online gaming.

This review is structured as follows. First, we elaborate on the proliferation and advantages of online gaming. Next, we present previous work on the causes of and means to prevent disruptive behaviour in online gaming. Subsequently, we review the literature on positive behaviour interventions and their uses across various domains to delineate the study’s research questions. Following, we present the methodology and data collection procedure of this systematic review. After we report the findings, we conclude the study with a discussion of the results, limitations, and a summary highlighting the relevance of this topic and avenues for further research.

Background and related work

Online gaming

Gaming, particularly the trend of gaming at home, started to gain popularity at the end of the twentieth century, largely driven by the advancement and expansion of gaming consoles such as Sega’s ‘DreamCast’, Sony’s ‘PlayStation’, and Nintendo’s ‘Super Nintendo’ (Griffiths et al., 2003). Gaming entailed initially little interaction between people since games were mostly played offline, and to play with other people, players would have to be present in the same room. Online gaming emerged following the proliferation of the internet as well as the progress of computers and console design and manufacturing (Sublette & Mullan, 2012). Moreover, the internet increasingly became a ‘gaming forum’ and new games were developed that allowed individuals to connect virtually to play together in multiplayer online games (MOGs; Freitas & Griffiths, 2009).

In the past few years, multiplayer online gaming has become one of the most common sources of entertainment (Ballabio et al., 2017; Neto et al., 2017). This growth was amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic; worldwide, the time people spent gaming online increased by 39 per cent (Clement, 2021) and the frequency of playing online multiplayer games increased by 60 per cent during the pandemic (Clement, 2021). Multiplayer online games (Griffiths et al., 2003) are characterised by their fictional atmosphere that focuses on immersion and interactivity with other players through the use of in-game chat text or voice communication; they have a narrative and organised missions that require critical thinking, cooperation, and problem-solving tactics, as well as the creation of new circumstances produced by the social interaction of players (Susaeta et al., 2010). MOGs are seen as an environment with complex dynamics of social exchanges between individuals (Ang et al., 2007; Rezaei & Ghodsi, 2014). In this sense, these games are a development of existing standalone games and are commonly known as ‘virtual worlds’ as they are not merely games in the conventional rules-based sense, instead, they are “persistent social and material worlds, loosely structured by open-ended narratives, where players are largely free to do as they please” (Paraskeva et al., 2010; Steinkuehler, 2004). MOGs comprise an extensive field of online games, which includes individuals playing with others in teams or alliances and competition (Adams et al., 2019; Barnett & Coulson, 2010a, b; Raith et al., 2021).

Playing online games, including MOGs, has several benefits. First, gaming has been shown to improve reaction times, hand and eye coordination, and spatial visualisation, as well as self-esteem (Griffiths, 2019). Additionally, online games have been used for educational purposes in school contexts (Griffiths, 2019) and have been shown to enhance children’s creativity (Jackson et al., 2012). Furthermore, Russoniello et al. (2013) have argued that casual gaming is correlated with a decrease in depressive thoughts and other symptoms in a group of individuals with diagnosed depression. Arguably, one of the biggest benefits of online gaming is social connectivity facilitated through teamwork play and chat functions (Prochnow et al., 2020). These interactions not only help to extend existing relationships but also foster new online friendships (Prochnow et al., 2020). Despite the stereotypes regarding video game players being socially segregated from society, over 63 per cent of players interact with other people online through games (Hilvert-Bruce & Neill, 2020; Prochnow et al., 2020). Social interaction among players further helps gain and improve prosocial skills and cooperative behaviour (Ferguson & Garza, 2011; Gentile et al., 2009).

Disruptive behaviour in online gaming and countermeasures

Despite these benefits, online games are also associated with various disruptive behaviours (Gandolfi & Ferdig, 2022). Disruptive behaviour manifests as offensive interactions between players, such as harassment, verbal abuse, or flaming, and disruptive gameplay that breaches standards and social norms established by game developers and gaming companies, such as griefing, spamming, and cheating (Poeller et al., 2023). Disruptive behaviour has been documented in particular in the multiplayer online gaming environment (Kordyaka et al., 2023), possibly because these games afford complex social interactions between players through text or voice chat messages (Ang et al., 2007; Deslauriers et al. 2020; Rezaei & Ghodsi, 2014).

Evidence from other online settings (Kou & Gui, 2021) further emphasises that disruptive behaviour may be facilitated in MOGs due to perceptions of low social-mediated presence (Kim & Chang, 2017). Disruptive behaviour is also more likely to occur when playing with strangers than with friends (Liu & Agur, 2023; Shen et al., 2020). Disinhibition (or, online toxic disinhibition (Neto et al., 2017; Suler, 2004), which is expected to be elevated under conditions of high perceived discursive or visual anonymity (Hollenbaugh & Everett, 2013; Suler, 2004), solipsistic introjection (i.e. self-constructed features of others), dissociative imagination (i.e. alternative reality), and lack of authority figures, have also been proposed as explanations of disruptive behaviour online (Hollenbaugh & Everett, 2013; Kordyaka & Kruse, 2021; Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, 2012). More precisely, in online settings, individuals are thought to experience liberty to express themselves in a way they would abstain from displaying in offline environments as the psychological processes that suppress disruptive reactions are likely reduced (Beres et al., 2021; Suler, 2004).

Given the high prevalence of disruptive behaviour in online gaming (Bryter, 2020; Cary et al., 2020), game developers and gaming companies have introduced a range of interventions. Reporting systems are a commonly used strategy to address disruptive behaviour (Adinolf & Turkay, 2018; Kou, 2020; Kou & Gui, 2021), combined with punishment for players exhibiting disruptive behaviour (Adinolf & Turkay, 2018; Kwak et al., 2015). Another option entails allowing players to mute and block other players (Adinolf & Turkay, 2018). In addition, tools for the automated detection of hate and disruptive behaviour in chat messages have been developed. Software and machine learning systems, normally used for document categorisation, topic recognition, and sentiment analysis have proven useful in identifying online disruptive behaviour using components of chat messages, however, disruptive behaviour detection is fundamentally more challenging and complex (Salawu et al., 2020). For example, alarmingly these automated detection systems are commonly inadequate as players can easily dodge them by omitting letters or replacing characters with numbers or special characters when sending hateful messages or selecting usernames (Canossa et al., 2017).

Although report systems are a common standard for many multiplayer online games, a survey of players showed that 51.3 per cent agreed that there are not enough tools available to deal with disruptive behaviour in the immediate situation or to prevent it from happening in the first place (Pohjanen, 2018). Not surprisingly, in this same survey, over 72 per cent of participants indicated that they found report systems to be ineffective in reducing toxic behaviour (Pohjanen, 2018). Similarly, another survey demonstrated that 62 per cent of participants agreed that companies should do more to make online games safer, 58 per cent shared that targets of this sort of behaviour should have more legal recourse and 55 per cent noted that in-game conversations should be monitored (ADL, 2019). Importantly, there is evidence to suggest that disruptive behaviour is not easily extinguished with punishment (Monge & O'Brien, 2022; Smith, 2021) and that players do not believe that the existing system achieves its intended goals (Blackburn & Kwak, 2014). Given the low effectiveness of current countermeasures, players are at risk of being exposed, repeatedly, to various forms of disruptive behaviour (Zargham et al., 2023). Consequently, players have started to normalise disruptive behaviour and mimic it, thus, enabling the further dissemination of harmful activities (Huesmann, 2018).

Positive behaviour strategies

Similar to online gaming, behavioural violations also occur in educational and health environments or workplaces (Madigan et al., 2016). Here, punitive measures are applied as well. However, the latter has been found to fail to explicitly educate individuals on more socially accepted behaviours and is, in many cases, the least efficient intervention (Madigan et al., 2016). In fact, in some circumstances, punishment can reinforce and enhance negative behaviour. For instance, it was shown that suspending young people from education for disruptive behaviour increases negative responses to authority (Madigan et al., 2016).

Positive behaviour interventions are an alternative to punitive approaches; they started to gain popularity in the 1980s and 1990s and have their roots in Applied Behaviour Analysis (MacDonald & McGill, 2013). Although some disagreement persists around the definition of positive behaviour strategies, they are generally understood as a practical approach intended to encourage individuals' achievements and improve the overall atmosphere of an environment (Pugh & Chitiyo, 2011). Notably, positive behaviour interventions may focus on (a) changing the setting before disruptive behaviours take place; (b) teaching and promoting appropriate behaviours through self-management and functional communication; (c) guaranteeing that suitable behaviours are regularly reinforced and that disruptive behaviours are discouraged; and (d) responding to behaviours so as to enhance safety and dignity, while reducing disruptive behaviour (McClean & Grey, 2012). The most commonly used interventions are the good behaviour game and bystander interventions.

The good behaviour game strategy was established by Barrish et al. (1969) to decrease disruptive behaviour through competition for rewards in groups (Keenan et al., 2000). Rewards are applied or deducted to all members of a group, based on all team members’ behaviour (Sewell, 2020). More positive and less disruptive behaviour by members, that is, the following of specified rules or norms, results in more rewards for all (Sewell, 2020). The good behaviour game has been implemented in a range of different environments (Coombes et al., 2016; Kellam et al., 2008; van Lier 2003, 2004). Specifically, participants of the good behaviour game have demonstrated a decrease in bullying behaviour, anti-social and aggressive patterns, criminal activity, drug and alcohol-related issues, and mental health problems (Coombes et al., 2016).

Promoting active bystander intervention is another common positive behaviour strategy that emphasises the role of peers and community members (McMahon & Banyard, 2012). Bystanders are individuals who are present when disruptive behaviour occurs; they are neither the aggressor/bully nor the victim (Polanin et al., 2012). Active bystanders may interfere to prevent or de-escalate an incident or comfort the victim (Macaulay et al., 2022; Polanin et al., 2012). Thus, active bystanders, unless they endorse the aggressor, are expected to reduce the likelihood and negative impact of disruptive behaviour. To achieve such active bystander intervention, people are educated about how to identify circumstances that may become problematic and how to interfere to reduce the escalation of disruptive incidents (Coker et al., 2019).

The present research

Positive behaviour interventions for online gaming

Although common in several settings, positive behaviour interventions have to date not been explored as a countermeasure in online gaming. This is surprising, not least because similar types of disruptive behaviour, that is, harassment, anti-social behaviour, bullying, negative peer interaction, sexual violence, and hate speech can be observed online and offline (Alvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018; Bulanda et al., 2020; Groves & Austin, 2019; Monge & O’Brien, 2022; Royen et al., 2017).

On a practical note, online games already include some of the features that are required to implement positive behaviour interventions. Tootling and (positive) peer reporting are perhaps the most easily implemented since games already enable negative reporting. Furthermore, if players are part of a group, they are automatically in the presence of bystanders. Players are typically not encouraged to intervene if they observe disruptive behaviour of fellow team players; negative reporting (i.e., passive bystander intervention) is the most common tactic. However, players could be educated about and given additional tools to promote, for instance, counter-speech which has been shown to serve as a deterrent and helped diminish the impact of hate speech on victims (Garland et al., 2022; Obermaier et al., 2021). The good behaviour game can also be implemented in multiplayer online gaming. If the game involves competitive play, a team could gain extra rewards after each game if everyone within the team follows all the established rules. These rules would be highlighted to players before the game and would mainly focus on accepted social behavioural norms (i.e., social norms related to positive behaviour and against disruptive behaviour). Automated detection and verification of compliance and/or reporting systems are required to confirm whether behaviours were indeed positive or disruptive. In this context, the risk of false positives and negatives must be acknowledged to avoid unfair treatment (Badjatiya et al., 2019).

Moreover, positive behaviour strategies could be effective in online gaming even if not all players adopt them; the latter would perhaps be unrealistic to expect. In fact, there is evidence to show that if only a quarter of a gaming community promotes a new norm, the larger group will come to endorse it (Poeller et al., 2023). Lastly, even if positive behaviour strategies have largely been applied offline, similarities between online and offline contexts justify their consideration for the online gaming environment. More precisely, according to Barnett and Coulson (2010a, b), multiplayer online games in particular mimic the physical world with respect to the importance of social interactions and communication. For example, in online gaming, players agree that collaboration outweighs individual skills (Kou & Gui, 2014; Poeller et al., 2023). Players further stated the importance of attempting to show praise and supportive behaviour to create positive environments, intending to promote similar actions in other players (Poeller et al. 2023). Other studies have highlighted that early positive communication in games raises the likelihood of sustained communication and pro-social interaction (Dabbish et al., 2012).

Furthermore, societal norms, standards, and institutional mechanisms apply in online and offline settings (Young & Tseng, 2008). In other words, social spaces offline or online are governed by implicit or explicit societal agreements about acceptable behaviour; it is presumed that every individual follows the norms, which may change over time (Kirman et al., 2012), to ensure progress and well-being of the community (Boucher & Kelly, 2003). Additionally, as with public assembly places in the physical world, individuals typically encounter barriers to how they can behave in online settings (Dempsey et al., 2009). Importantly, behavioural norms online and offline can be actively shaped by internal and external actors to encourage positive behaviour (Shores et al., 2014).

Research goals and questions

Previous research on disruptive behaviour in online gaming has focused on identifying potential individual-level and contextual causes and developing software to detect different types of disruptive behaviour (Adinolf & Turkay, 2018; Beres et al., 2021; Kordyaka et al., 2022; Kou, 2020; Kou & Gui, 2021; Märtens et al., 2015; Reid et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2020). However, disruptive behaviour is profoundly more challenging and complicated (Salawu et al., 2020), hence concrete novel countermeasures must be developed. With this aim, the objective of this review is to advance the literature and investigate whether positive behaviour interventions that have been implemented across a variety of offline settings are indeed suitable to complement existing punitive measures to prevent disruptive behaviour in online gaming. We further seek to specify which positive behaviour interventions are most applicable in the online gaming context. To draw these conclusions, we, first, systematically summarised which positive behaviour strategies have been used across different settings thus far (Research Question 1). Additionally, we evaluated how effective different positive behaviour strategy interventions were in addressing various disruptive behaviours (Research Question 2).

In answering these questions, we make two contributions to the literature. Importantly, we respond to the call to identify alternative interventions beyond punishment to deter disruptive behaviour in online gaming (Poeller et al., 2023). Specifically, we seek to explore the possible application of strategies that rely on the existing tools and would not rule out the maintenance of strategies to punish disruptive behaviour (Poeller et al., 2023). In addition, we consider the option to extend the repertoire of current interventions to include such that are enacted as preventive measures, not after disruptive behaviour has occurred (Wijkstra et al., 2023). We also contribute to the literature on positive behaviour strategies that have to date not been summarised systematically to denote which interventions are widely applied, addressing which behaviour, and with which result. Providing these insights can highlight gaps in the literature and avenues for future studies or methodological improvements.

Methodology

The protocol of this systematic review was registered on the Open Science Framework,Footnote 2 where both the protocol and a record of exclusion/inclusion decisions have been made available.

Study identification and types of studies

Articles included in this review were identified using an electronic database search between January and September 2022. The search was conducted in the following academic databases: Web of Science, PsycInfo, ACM digital library, Scopus, and Criminal Justice database. To gather the broadest collection of potential studies the search was conducted using the following search terms: (strateg* OR technique* OR mechanism* OR approach* OR system OR systems OR tool* OR cope) AND (communit* OR peer* OR ingroup OR group) AND (promote OR encourage OR endorse OR stimulate or avert or avoid or counter or mitigate) AND (“positive behaviour” OR “positive behavior” OR “norm adherence” OR “disruptive behaviour” OR “toxic behaviour” OR “toxic behavior” OR haras* OR disturbing OR upsetting OR “rule-breaking” OR “disruptive behavior”).

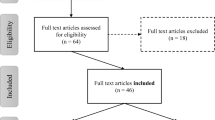

Several pilot searches were conducted prior to the final search (Table 1) to avoid a large number of unrelated subjects being gathered (e.g., the search term toxicity was linked with medicine) but still ensure that relevant records were identified. The final search string yielded a total of 2222 citations (Fig. 1).

Inclusion criteria

After removing duplicates, 1872 articles were submitted to an initial screening process in which titles and abstracts were assessed (Fig. 1). Throughout the whole screening process, a label was added to each article to justify the reason for inclusion and exclusion. Available peer-reviewed articles were included in this systematic review, comprising various study designs and methods, as well as PhD theses, industry reports, or government and institutional publications. Opinion pieces, news pieces, book reviews and commentaries were excluded. According to the inclusion criteria (Table 2), articles had to undoubtedly discuss approaches to encourage positive behaviour, regardless of the setting. Articles were also included if prevention of disruptive behaviour was explored; this included evidence of existing or potential examples of positive behaviour. Articles in English were included as well as any other language when translation was available. No restriction was imposed on the country where the study was conducted, assuming the language criteria mentioned above were met. A total of 1711 articles were excluded, and 161 articles were submitted to the second screening procedure (Fig. 1). The second screening consisted of a more in-depth examination based on the articles’ full text. Following this process, 22 articles met all inclusion standards (Fig. 1). The study title, author, year of publication, journal, keywords, abstract, article type, hypotheses, participants, study design and methodology, main results, further research, research area, area of intervention, country of intervention, and intervention/coping mechanism were extracted.

Coding and inter-rater reliability (IRR)

Two of the authors validated the initial coding results to safeguard good inter-rater reliability and prevent individual bias in the selection and examination of the articles. Specifically, we allocated a random sample of 100 articles from the initial list of references for examination and coding. There was a 93 per cent agreement (Cohen’s K = 77.7), which demonstrated a good level of agreement. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by deliberation.

Results

Before describing the findings of the 22 included reports, it is worth making two overall observations. Firstly, as highlighted in this paper’s introduction section, disruptive behaviour has continuously been a topic of interest for scholars in a wide range of subjects (Fig. 2). Secondly, over the past few years, there has been an increase in the number of research outputs focusing on the use of positive behaviour as a preventive measure for disruptive behaviour (Fig. 3), highlighting a shift from individuals’ punishment to communities and relationship building (Marais & Meier, 2010).

Targeted individuals/groups

Of the 22 included records, 15 were experimental studies with human participants (Table 3). The majority of these participants were students, reflecting the fact that most studies were conducted in educational environments (i.e., 11 out of 15 studies). Having said this, participants’ demographic characteristics varied. The age of participants ranged from 9 to 50+ years old (Table 3); other characteristics such as ethnicity and professional occupation differed as well across studies.Footnote 3

Disruptive behaviour problems

The specific disruptive behaviour problems that were explored also varied across articles (Table 3). The most common disruptive behaviour problem identified was classroom disruptive behaviour (i.e., 11 out of 22 records), including aggressive behaviour, negative peer interaction,

such as name-calling and taking peers’ materials, or non-compliance. The second most referenced problem was harassment, which included sexual harassment and violence, bullying and cyberbullying, and hate speech (i.e., 10 out of 22 records). Finally, the least referenced concern was substance abuse, antisocial behaviour, and depression (i.e., 1 out of 22 records respectively). Interestingly, although the aforementioned behaviours were identified as the target disruptive behaviour, no article provided a definition of the concept of disruptive behaviour.

Positive behaviour strategies

The main aim of this systematic review was to identify interventions that had been implemented to promote positive behaviour across different settings (Research Question 1). The most commonly referenced strategy was promoting active bystander behaviour (i.e., 4 out of 22 studies). Equally common was the strategy of the good behaviour game (i.e., 3 out of 22 studies) (Bowman-Perrott et al., 2016). Other strategies such as tootling, positive peer reporting, school-wide positive behavioural interventions, and support (SWPBIS), and group contingencies were also identified in the studies. Tootling and peer-positive reporting consist of reporting positive behaviour; this means that pupils are involved in positive peer supervising and report their peers’ positive, prosocial actions. In some instances, the aforementioned strategies were coupled with an interdependent group contingency reward for those with the most reports of positive behaviour (Chaffee et al., 2020; McHugh et al., 2016).

Outcome of the intervention

Speaking to Research Question 2, most interventions had prevention as their primary goal followed by the aims of reducing and coping with disruptive behaviour (Table 3). Practically every intervention generated positive and relevant results (Table 3). This demonstrates the effectiveness of using positive behaviour strategies to prevent, reduce, and cope with disruptive behaviour in a variety of different settings. Having said this, as shown in Table 3, interventions were not equally effective. It could be speculated that the setting and type of the intervention, the target population, and the outcome affect the interventions’ effectiveness. However, the good behaviour game, positive peer reporting and tootling, and bystander interventions demonstrated promising results; they significantly reduced disruptive behaviour and promoted positive behaviour amongst individuals with moderate to large effects.

Discussion

This systematic review sought to summarise positive behaviour strategies that had been implemented for the prevention and reduction of disruptive behaviour in a variety of different settings as well as denote the interventions’ effectiveness. In doing so, we aimed to identify concrete positive behaviour strategies that could be implemented in online gaming to complement current (less than ideal) punitive measures to counter disruptive behaviour in this context. Results, firstly, documented that there has been an increase in the number of publications focusing on positive behaviour interventions and their impact on disruptive behaviour, with approximately 72 per cent of the identified papers published after 2018. In other words, researchers seem to have shifted their focus on preventative measures (Marais & Meier, 2010), which is in line with research suggesting that this is a more effective approach for promoting behaviour change than punishment (Groves & Austin, 2019; McHugh et al., 2016; Moreira et al., 2019; Poeller et al., 2023).

The most common positive behaviour strategies in different physical settings discussed in previous research were promoting active bystander intervention, the good behaviour game, tootling, and positive peer reporting. In principle, all these approaches could be suitable for online gaming environments as well (Alvarez-Benjumea & Winter, 2018). Notably, the strategies assessed in this review were explored in samples who ranged in age from nine to 50+ years, which is similar to the typical age range of online video game players (Ghuman & Griffiths, 2012; Williams et al., 2008; see also Baker, 2023). Having said this, findings suggest that certain positive behaviour interventions may be more promising for the online (multiplayer) gaming context because they attain relevant outcomes more consistently.

Tootling interventions achieved moderate to large/strong effects in experimental studies; bystander interventions showed positive results in survey studies; and the good behaviour game achieved moderate to large impact in experimental studies (Banyard et al., 2022; Chaffee et al., 2020; Groves & Austin, 2019; Haydon et al., 2022; McHugh et al., 2016). Thus, causal conclusions about the effect of the aforementioned strategies can only be drawn for tootling and the good behaviour game. In addition to the robustness of the documented effectiveness of interventions, those two strategies rely on tools that are already employed in current countermeasures (i.e., reporting systems, reward mechanisms) or existing game design features (i.e., team play) and are possibly more easily (technically) implemented. For instance, League of Legends, one of the most played multiplayer online games (Kwak et al., 2015), offers several possibilities to implement positive behaviour strategies. A reporting system enables players to report teammates who display disruptive behaviour and includes the option of honouring a player after a game resulting in a reward. To introduce tootling and the positive behaviour game, players could be encouraged to report disruptive as well as positive behaviours (i.e., examples of positive game behaviour will have to be announced and included in the reporting system). Players with the most positive reports should be able to collect meaningful rewards or have their positive behaviour actions highlighted to others.

Although bystander interventions are in principle promising to prevent and reduce disruptive behaviour incidents (Herry et al., 2021), promoting active bystander behaviour might prove to be more challenging to implement in online gaming. Active bystander interventions vary depending on the context (Cleemput et al., 2014, DeSmet, et al., 2012). In online environments, they can include addressing the perpetrator, getting assistance from an authority figure, or speaking to and offering assistance to the victim (Moxey & Bussey, 2020; Mulvey et al., 2019). However, the role of bystanders in online environments is not well comprehended, research has mostly concentrated on perpetrators (Patterson et al., 2017). Research highlights that young individuals commonly encounter disruptive behaviour incidents online but only a small percentage of them intervene (Lenhart et al., 2011; O’Moore, 2012). This is because the willingness for bystander intervention online is driven by personal and contextual factors such as the victim’s and bystander’s anonymity, relationship to the victim, victim response, and individuals’ knowledge about bystander interventions (Banyard et al., 2022; Macaulay et al., 2022; Rudnicki et al., 2023; Song & Oh, 2018). Usually, in online gaming, players have no established relationship with the victims of disruptive behaviour, which would reduce the likelihood of bystander intervention. Anonymity is one of the most predominant characteristics of online gaming but is also a contextual factor that undermines bystander intervention; therefore, it is exceptionally challenging to establish individual relationships among players. Thus, to provide conditions that facilitate bystander intervention, the design of games would have to be changed in a more elaborate manner than for tootling or the good behaviour game. In addition to this, it is essential to establish more positive communities to promote better and healthier interactions among players. Research also established that individuals must be educated in bystander behaviour to successfully intervene when incidents take place (Latane & Darley, 1970; O’Brien et al., 2021). To do this, gaming companies such as the developers of League of Legends, have the possibility of investing in educating their communities to be aware and act as active bystanders.

This systematic review also adds to the literature on positive behaviour strategies. First, we highlighted a lack of experimental studies testing all positive behaviour strategies. As such, it is, to date, not possible to draw causal conclusions about the impact of the full range of positive behaviour strategies. Existing research has also focused on evaluating one positive behaviour strategy within one singular setting. We did not identify any comparative studies that would allow us to gain insights about which positive behaviour intervention works best in which context. Future research on positive behaviour strategies, in the context of online gaming or other domains, should address these points to promote, ultimately, the proliferation of the interventions as alternatives to punitive measures.

Limitations

Some limitations of this systematic review should be considered. First, the analysis may have been affected by positive result bias (i.e., publication bias). This limitation could be addressed, for example, with funnel plots if the focus was on quantitative results. As the included articles applied a wide range of qualitative and quantitative research methods the detection of publication bias is challenging. Moreover, although the literature search process was systematic, it is possible that some studies were unintentionally overlooked. The review drew on works in several disciplines outside the authors’ field of expertise. However, further domains, that we are not aware of, might have explored positive behaviour strategies using terminology that was not included in the search. Finally, we recognise that relevant literature published after September 2022 is not included in this systematic review.

Conclusion

As stated by Poeller and colleagues (2023), “interventions that encourage positive behaviour and proactively create positive gaming spaces are still in their infancy and little is known about how players respond to positivity” (p.1). This review has identified positive behaviour strategies that have been implemented in different settings and that could aid in preventing and reducing disruptive behaviour in online gaming. There are several promising opportunities for transferability, however, the good behaviour game and tootling stand out based on the promising significant impact demonstrated in experimental studies and their similarities with current countermeasures. Future research should focus on assessing optimal conditions for the implementation of these new interventions in (multiplayer) online gaming. Those insights will contribute to advancing the understanding of how positive gaming spaces can be created.

Data availability

All underlying data, including the coding decisions, will be made available upon request to the first author.

Notes

New study finds prevalent and harmful harassment and discrimination within NHS healthcare workforce. (2020, December 16). Retrieved from King's College London: https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/new-study-finds-prevalent-and-harmful-harassment-and-discrimination-within-nhs-healthcare-workforce.

References

Abdelmonem, A. (2022). Disciplining bystanders: (Anti)carcerality, ethics, and the docile subject in HarassMap’s “the harasser is a criminal” media campaign in Egypt. Feminist Media Studies, 22(2), 238–253.

Adams, B. L., et al. (2019). Internet gaming disorder behaviors in emergent adulthood: A pilot study examining the interplay between anxiety and family cohesion. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, Issue, 17, 828–844.

Adinolf, S. & Turkay, S. (2018). Toxic Behaviors in Esports Games. s.l., CHI.

ADL (2019). Free to play? Hate, harassment and positive social experiences in online games. [Online]. https://www.adl.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/2022-12/Free%20to%20Play%2007242019.pdf. Accessed 26 Apr 2024.

Akhter, R., Wilson, J. K., Haque, S. E., & Ahamed, N. (2022). Like a caged bird: the coping strategies of economically empowered women who are victims of intimate partner violence in Bangladesh. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(11–12), NP9040–65.

Alliance, F. P. (2021). About the fair play alliance. [Online]. https://fairplayalliance.org/about/. Accessed 26 Apr 2024.

Alvarez-Benjumea, A., & Winter, F. (2018). Normative change and culture of hate: An experiment in online environments. European Sociological Review, 34(2), 223–237.

Ang, C. S., Zaphiris, P., & Mahmood, S. (2007). A model of cognitive loads in massively multiplayer online role playing games. Interacting with Computers, 19(2), 167–179.

Badjatiya, P., Gupta, M., & Varma, V. (2019). Stereotypical bias removal for hate speech detection task using knowledge-based generalizations. San Francisco: WWW’19.

Baker, N. (2023). Online gaming statistics 2023. https://www.uswitch.com/broadband/studies/online-gaming-statistics/. Accessed 6 July 2023.

Ballabio, M., et al. (2017). Do gaming motives mediate between psychiatric symptoms and problematic gaming? An empirical survey study. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(5), 397–408.

Banyard, V. L., et al. (2019). Evaluating a gender transformative violence prevention program for middle school boys: A pilot study. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 165–173.

Banyard, V., Waterman, E. A., Edwards, K. M., & Valente, T. W. (2022). Adolescent peers and prevention: Network patterns of sexual violence attitudes and bystander actions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), NP12398–NP12426.

Barnett, J., & Coulson, M. (2010a). Virtually real: A psychological perspective on massively multiplayer online games. Review of General Psychology, 14, 167–179.

Barnett, J., & Coulson, M. (2010b). Virtually real: A psychological perspective on massively multiplayer online games. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 167–179.

Barrish, H. H., Saunders, M., & Wolf, M. M. (1969). Good Behavior Game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 2, 119–124.

Beres, N. A. et al. (2021). Don’t you know that you’re toxic: Normalization of toxicity in online gaming. Japan, CHI.

Bierman, K. L., et al. (1999). Initial impact of the Fast Track prevention trial for conduct problems: II. Classroom effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 648–657.

Blackburn, J. & Kwak, H. (2014). STFU NOOB! Predicting Crowdsourced decisions on toxic behavior in online games. In: Seoul, International world wide web conference committee (IW3C2).

Boucher, D., & Kelly, P. (2003). The social contract from Hobbes to Rawls. Routledge.

Bowen, B., Privitera, M. R., & Bowie, V. (2011). Reducing workplace violence by creating healthy workplace environments. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3(4), 185–198.

Bowman-Perrott, L., et al. (2016). Promoting positive behavior using the good behavior game: A meta-analysis of single-case research. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(3), 180–190.

Bryter. (2020). Female gamer survey. Bryter.

Bulanda, J. J., Conteh, A. B., & Jalloh, F. (2020). Stress and coping among university students in Sierra Leone: Implications for social work practice to promote development through higher education. International Social Work, 63(4), 510–523.

Bulla, A. J., & Frieder, J. E. (2018). Self-management as a class-wide intervention: An evaluation of the “Self & Match” system embedded within a dependent group contingency. Psychology in the Schools, 55, 305–322.

Canossa, A., et al. (2017). For honor, for toxicity: detecting toxic behavior through gameplay. ACM on Human-Computer Interaction.

Cary, L. A., Axt, J., & Chasteen, A. L. (2020). The interplay of individual differences, norms, and group identification in predicting prejudiced behavior in online video game interactions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50, 623–637.

Castello, J. (2018, August 17). Foul play: tackling toxicity and abuse in online video games. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/games/2018/aug/17/tackling-toxicity-abuse-in-online-video-games-overwatch-rainbow-seige

Chaffee, R. K., et al. (2020). Effects of a class-wide positive peer reporting intervention on middle school student behavior. Behavioral Disorders, 45(4), 224–237.

Cleemput, K. V., Vandebosch, H., & Pabian, S. (2014). Personal characteristics and contextual factors that determine “helping”, “joining in”, and “doing nothing” when witnessing cyberbullying. Aggressive Behavior, 40(5), 383–396.

Clement, J. (2021). Coronavirus: impact on the gaming industry worldwide, s.l. Simon-Kucher & Partners.

Coker, A. L., et al. (2019). Bystander approaches have been recognized as promising prevention strategies for violence prevention. Journal of Family Violence, 34, 153–164.

Collins, T. A., Hawkins, R. O., Heidelburg, K., & Hill, K. (2019). Group Contingencies. In K. C. Radley & E. H. Dart (Eds.), Handbook of Behavioral Interventions in School: Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (pp. 204–233). Oxford University Press.

Coombes, L., Chan, G., Allen, D., & Foxcroft, D. R. (2016). Mixed-methods evaluation of the good behaviour game in english primary schools. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, Issue, 26, 369–387.

Dabbish, L., Kraut, R. & Patton, J. (2012). Communication and commitment in an online game team. s.l., CHI '12.

Dempsey, A. G., Sulkowski, M. L., Nichols, R., & Storch, E. A. (2009). Differences between peer victimization in cyber and physical settings and associated psychosocial adjustment in early adolescence. Psychology in the Schools, 46(10), 962–972.

Deslauriers, P., St-Martin, L. I. L. & Bonenfant, M. (2020). Assessing toxic behaviour in dead by daylight: Perceptions and factors of toxicity according to the game’s official subreddit contributors. The International Journal of Computer Game Research, 20(4).

DeSmet, A., Cleemput, K. V., Bastiaensens, S., & Poels, K. (2012). Mobilizing bystanders of cyberbullying: An exploratory study into behavioural determinants of defending the victim. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 181, 58–63.

Elgabry, M., Nesbeth, D., & Johnson, S. D. (2020). A systematic review of the criminogenic potential of synthetic biology and routes to future crime prevention. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 8(571672).

Fazackerley, A. (2023, June 24). Disruptive behaviour leaves excluded pupils’ units in England ‘full to bursting’. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/jun/24/disruptive-behaviour-leaves-excluded-pupils-units-in-england-full-to-bursting

Ferguson, C. J., & Garza, A. (2011). Call of (civic) duty: Action games and civic behavior in a large sample of youth. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 770–775.

Ford, K., Bellis, M. A., Hill, R., & Hughes, K. (2022). An evaluation of a short film promoting kindness in Wales during COVID-19 restrictions #TimeToBeKind. BMC Public Health, 22, 583.

Freitas, S. d., & Griffiths, M. (2009). Massively multiplayer online role-play games for learning. In R. E. Ferdig (Ed.), Handbook of research on effective electronic gaming in education (pp. 51–66). IGI Global.

Gandolfi, E., & Ferdig, R. E. (2022). Sharing dark sides on game service platforms: Disruptive behaviors and toxicity in DOTA2 through a platform lens. Convergence International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 28(2), 468–487.

Garland, J., et al. (2022). Impact and dynamics of hate and counter speech online. EPJ Data Science, 11(1), 3.

Gentile, D. A., et al. (2009). The effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behaviors: international evidence from correlational, longitudinal, and experimental studies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(6), 752–763.

Ghuman, D., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). A cross-genre study of online gaming: Player demographics, motivation for play, and social interactions among players. International Journal of Cyber Behavior, Psychology and Learning, 2(1), 13–29.

Griffiths, M. D. (2019). The therapeutic and health benefits of playing video games. In A. Attrill-Smith, C. Fullwood, M. Keep, & D. J. Kuss (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of cyberpsychology (pp. 485–505). Library of Psychology.

Griffiths, M. D., Davies, M. N., & Chappell, D. (2003). Breaking the stereotype: the case of online gaming. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 6(1), 81–91.

Groves, E. A., & Austin, J. L. (2019). Does the good behavior game evoke negative peer pressure? Analyses in primary and secondary classrooms. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52, 3–16.

Haydon, T., Kennedy, A., Murphy, M., & Boone, J. (2022). Positive peer reporting for middle school students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic, 58(4), 273–279.

Herry, E., Gonultas, S., & Mulvey, K. L. (2021). Digital era bullying: An examination of adolescent judgments about bystander intervention online. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 76, 101322.

Hilvert-Bruce, Z., & Neill, J. T. (2020). I’m just trolling: The role of normative beliefs in aggressive behaviour in online gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 303–311.

Hollenbaugh, E. E., & Everett, M. K. (2013). The effects of anonymity on self-disclosure in blogs: An application of the online disinhibition effect. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18, 283–302.

Huesmann, L. R. (2018). An integrative theoretical understanding of aggression: A brief exposition. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 119–124.

Ialongo, N. S., et al. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of the combination of two school-based universal preventive interventions. Developmental Psychology, 55(6), 1313–1325.

Jackson, L. A., et al. (2012). Information technology use and creativity: Findings from the Children and Technology Project. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 370–376.

Keenan, M., Moore, J. L., & Dillenburger, K. (2000). The good behaviour game. Child Care in Practice, 6(1), 27–38.

Kellam, S. G., et al. (2008). Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95, S5–S28.

Kim, H., & Chang, Y. (2017). Managing online toxic disinhibition: The impact of identity and social presence. SIGHCI.

Kirman, B., Lineham, C. & Lawson, S. (2012). Exploring mischief and mayhem in social computing or: how we learned to stop worrying and love the trolls. s.l., CHI'12.

Kordyaka, B., Jahn, K., & Niehaves, B. (2020). Towards a unified theory of toxic behavior in video games. Internet Research, 30(4), 1081–1102.

Kordyaka, B., Klesel, M. & Jahn, K. (2019). Perpetrators in League of Legends: Scale Development and Validation of Toxic Behavior. s.l., Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences.

Kordyaka, B., & Kruse, B. (2021). Curing toxicity – developing design principles to buffer toxic behaviour in massive multiplayer online games. Safer Communities, 20(3), 133–149.

Kordyaka, B, et al. (2022). Understanding toxicity in multiplayer online games: The roles of national culture and demographic variables. s.l., 55th Hawaii international conference on system sciences.

Kordyaka, B. et al. (2023). The cycle of toxicity: Exploring relationships between personality and player roles in toxic behavior in multiplayer online battle arena games. s.l., CHI PLAY.

Kou, Y. (2020). Toxic behaviors in team-based competitive gaming: The case of league of legends. s.l., CHI.

Kou, Y. (2021). Punishment and its discontents: An analysis of permanent ban in an online game community. PACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW2).

Kou, Y. & Gui, X. (2014). Playing with strangers: Understanding temporary teams in league of legends. s.l., CHI PLAY’14.

Kou, Y. & Gui, X. (2021). Flag and flaggability in automated moderation. Yokohama, CHI’21.

Kowert, R. & Cook, C. L. (2022). The toxicity of our (virtual) cities: Prevalence of dark participation in games and perceived effectiveness of reporting tools. s.l., Hawaii International conference on system sciences.

Kwak, H., Blackburn, J. & Han, S. (2015). Exploring cyberbullying and other toxic behavior in team competition online games. In: Seoul, ACM conference on human factors in computing systems, pp. 3739–3748.

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1970). The unresponsive bystander: Why doesn’t he help? Appleton-Century Crofts.

Lenhart, A., et al. (2011). Teens, kindness and cruelty on social network sites: How American teens navigate the new world of digital citizenship. Pew Internet & American Life Project.

Liu, Y., & Agur, C. (2023). “After All, They Don’t Know Me” Exploring the psychological mechanisms of toxic behavior in online games. Games and Culture, 18(5), 598–621.

Lodge, J., & Frydenberg, E. (2005). The role of peer bystanders in school bullying: Positive steps toward promoting peaceful schools. Theory into Practice, 44(4), 329–336.

Macaulay, P. J., Betts, L. R., Stiller, J., & Kellezi, B. (2022). Bystander responses to cyberbullying: The role of perceived severity, publicity, anonymity, type of cyberbullying, and victim response. Computers in Human Behavior, 131, 107238.

MacDonald, A., & McGill, P. (2013). Outcomes of Staff training in positive behaviour support: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 25, 17–33.

Madigan, K., Cross, R. W., Smolkowski, K., & Strycke, L. A. (2016). Association between schoolwide positive behavioural interventions and supports and academic achievement: A 9-year evaluation. Educational Research and Evaluation, 22(7–8), 402–421.

Marais, P., & Meier, C. (2010). Disruptive behaviour in the Foundation Phase of schooling. South African Journal of Education, 30, 41–57.

Marsh, S. (2023, May 25). Half of British female gamers experience abuse when playing online. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/games/2023/may/25/half-of-british-female-gamers-experience-abuse-when-playing-online

Märtens, M., Shen, S., Iosup, A. & Kuipers, F. (2015). Toxicity detection in multiplayer online games. s.l., IEEE.

McClean, B., & Grey, I. (2012). A Component analysis of positive behaviour support plans. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37(3), 221–231.

McHugh, M. B., et al. (2016). Effects of tootling on classwide and individual disruptive and academically engaged behavior of lower-elementary students. Behavioral Interventions, 31, 332–354.

McMahon, S., & Banyard, V. L. (2012). When can i help? A conceptual framework for the prevention of sexual violence through bystander intervention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 13(1), 3–14.

Mitchell, B. S., Hatton, H., & Lewis, T. J. (2018). An examination of the evidence-base of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports through two quality appraisal processes. Journal of Positive Behaviour Interventions, 20(4), 239–250.

Monge, C. K., & O’Brien, T. C. (2022). Effects of individual toxic behavior on team performance in League of Legends. Media Psychology, 25(1), 82–105.

Moreira, F. T. L. D. S., Calloua, R. C. M., Albuquerqueb, G. A., & Oliveirac, R. M. (2019). Effective communication strategies for managing disruptive behaviors and promoting patient safety. Revista Gaúcha De Enfermagem, 40, e20180308.

Moxey, N., & Bussey, K. (2020). Styles of bystander intervention in cyberbullying incidents. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 2, 6–15.

Mulvey, K. L., et al. (2019). School and family factors predicting adolescent cognition regarding bystander intervention in response to bullying and victim retaliation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(3), 581–596.

Narhia, V., Kiiskic, T., & Savolainena, H. (2017). Reducing disruptive behaviours and improving classroom behavioural climate with class-wide positive behaviour support in middle schools. British Educational Research Journal, 43(6), 1186–1205.

Nash, P., Schlösser, A., & Scarr, T. (2015). Teachers’ perceptions of disruptive behaviour in schools: A psychological perspective. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 21(2), 167–180.

Neto, J. A. M., Yokoyama, K. M. & Becker, K. (2017). Studying toxic behavior influence and player chat in an online video game. Leipzig. In: Proceedings of the international conference on web intelligence.

Obermaier, M., Schmuck, D., & Saleem, M. (2021). I’ll be there for you? Effects of Islamophobic online hate speech and counter speech on Muslim in-group bystanders’ intention to intervene. New Media & Society., 25, 2339–2358.

Obrien, K. M., et al. (2021). Evaluating the effectiveness of an online intervention to educate college students about dating violence and bystander responses. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(13–14), NP7516–NP7546.

O’Moore, M. (2012). Cyber-bullying: The situation in Ireland. Pastoral Care in Education, 30(3), 209–223.

Paraskeva, F., Mysirlaki, S., & Papagianni, A. (2010). Multiplayer online games as educational tools: Facing new challenges in learning. Computers & Education, 54, 498–505.

Patterson, L. J., Allan, A., & Cross, D. (2017). Adolescent bystander behavior in the school and online environments and the implications for interventions targeting cyberbullying. Journal of School Violence, 16(4), 361–375.

Poeller, S., Dechant, M. J., Klarkowski, M. & Mandryk, R. L. (2023). Suspecting sarcasm: How league of legends players dismiss positive communication in toxic environments. s.l., CHI PLAY.

Pohjanen, A. E. (2018). Report, please! A survey on players’ perceptions towards the tools for fighting toxic behavior in competitive online multiplayer video games. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/59353/URN:NBN:fi:jyu-201808293951.pdf. Accessed 4 Aug 2023.

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2012). A meta-analysis of school-based bullying prevention programs’ effects on bystander intervention behavior. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 47–65.

Prochnow, T., Patterson, M. S., & Hartnell, L. (2020). Social support, depressive symptoms, and online gaming network communication. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 24(1), 49–58.

Pugh, R., & Chitiyo, M. (2011). The problem of bullying in schools and the promise of positive behaviour supports. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 12(2), 47–53.

Raith, L., et al. (2021). Massively multiplayer online games and well-being: A systematic literature review. Fontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–13.

Reid, E. et al. (2021). “Bad Vibrations”: Sensing toxicity from in-game audio features. s.l., IEEE.

Rezaei, S., & Ghodsi, S. S. (2014). Does value matter in playing online games? An empirical study among massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 252–266.

Rogers-Clark, C., Pearce, S., & Cameron, M. (2009). Management of disruptive behaviour within nursing work environments: A comprehensive systematic review of the evidence. JBI Library of Systematic Reviews, 7(15), 615–678.

Royen, K. V., Poels, K., Vandebosch, H., & Adam, P. (2017). “Thinking before posting?” Reducing cyber harassment on social networking sites through a reflective message. Computers in Human Behaviour, 66, 345–352.

Rubin, J. D., Blackwell, L., & Conley, T. D. (2020). Fragile masculinity: men, gender, and online harassment. Honolulu: CHI.

Rudnicki, K., Vandebosch, H., Voue, P., & Poels, K. (2023). Systematic review of determinants and consequences of bystander interventions in online hate and cyberbullying among adults. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(5), 527–544.

Russoniello, C., Fish, M. T., & O’Brien, K. (2013). The efficacy of casual videogame play in reducing clinical depression: a randomized controlled study. Games for Health Journal, 2(6).

Salawu, S., He, Y., & Lumsden, J. (2020). Approaches to automated detection of cyberbullying: A survey. EEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 11(1), 3–24.

Sewell, A. (2020). An adaptation of the Good Behaviour Game to promote social skill development at the whole-class level. Educational Psychology in Practice, 36(1), 93–109.

Shen, C., et al. (2020). Viral vitriol: Predictors and contagion of online toxicity in World of Tanks. Computers in Human Behavior, 108, 1–9.

Shores, K., He, Y., Swanenburg, K.L., Kraut, R., & Riedl, J. (2014). The identification of deviance and its impact on retention in a multiplayer game. In: s.l., 17th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work & social computing.

Smith, D. (2021). The state of disruptive behavior in multiplayer games—2021. https://blog.unity.com/games/the-state-of-disruptive-behavior-in-multiplayer-games-2021. Accessed 13 Apr 2024.

Song, J., & Oh, I. (2018). Factors influencing bystanders’ behavioral reactions in cyberbullying situations. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 273–282.

Steinkuehler, C. A. (2004). Learning in massively multiplayer online games. In: Santa Monica, International conference of the learning sciences.

Sublette, V. A., & Mullan, B. (2012). Consequences of play: A systematic review of the effects of online gaming. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10(1), 3–23.

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326.

Susaeta, H., et al. (2010). From MMORPG to a classroom multiplayer presential role playing game. Educational Technology & Society, 13(3), 257–269.

van Lier, P. A. C., Muthen, B. O., van der Sar, R. M., & Crijnen, A. A. M. (2004). Preventing disruptive behavior in elementary schoolchildren: Impact of a universal classroom-based intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 467–478.

van Lier, P. A., Verhulst, F. C., van der Ende, J., & Crijnen, A. A. (2003). Classes of disruptive behaviour in a sample of young elementary school children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(3), 377–387.

Villafranca, A., Hamlin, C., Enns, S., & Jacobsohn, E. (2017). Disruptive behaviour in the perioperative setting: A contemporary review. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 64, 128–140.

Wijkstra, M. et al. (2023). Help, my game is toxic! First insights from a systematic literature review on intervention systems for toxic behaviors in online video games. s.l., CHI PLAY.

Williams, D., Yee, N., & Caplan, S. E. (2008). Who plays, how much, and why? Debunking the stereotypical gamer profile. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13, 993–1018.

Young, M.-L., & Tseng, F.-C. (2008). Interplay between physical and virtual settings for online interpersonal trust formation in knowledge-sharing practice. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 11(1), 55–64.

Zargham, N. et al. (2023). Speaking up against toxicity: opportunities and challenges of utilizing courtesy as a game mechanic. Hamburg, CHI 23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TGM is the first and main contributor to the paper having worked towards all the steps and writing involved in this systematic review. SS and EM as supervisors have contributed to the writing of the paper and the contents of the discussion section, furthermore, EM has been the second IRR coder for this systematic review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Marques, T.G., Schumann, S. & Mariconti, E. Positive behaviour interventions in online gaming: a systematic review of strategies applied in other environments. Crime Sci 13, 14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-024-00208-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-024-00208-8