Abstract

Background

An experiment was conducted to evaluate the effects of feed restriction (FR) and sex on the quantitative and qualitative carcass traits of Morada Nova lambs. Thirty-five animals with an initial body weight of 14.5 ± 0.89 kg and age of 120 d were used in a completely randomized study with a 3 × 3 factorial scheme consisting of three sexes (11 entire males, 12 castrated males and 12 females) and three levels of feeding (ad libitum – AL and 30% and 60% FR).

Results

Entire males presented greater hot and cold carcass weights (P < 0.05), followed by castrated males and females. However, the hot carcass yield was higher for females and castrated males than for entire males. Luminosity values were influenced (P < 0.05) by sex, with entire males presenting higher values than castrated males and females. Females showed higher (P < 0.05) concentrations of linoleic acid and arachidonic acid in the meat of the longissimus thoracis muscle. The meat of animals submitted to AL intake and 30% FR showed similar (P > 0.05) concentrations, and the concentrations of palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid and conjugated linoleic acid were higher (P < 0.05) than those of animals with 60% FR. The meat of females had a higher ω6/ω3 ratio and lower h/H ratio, and females had greater levels of feeding. The meat of animals on the 60% FR diet had a greater ω6/ω3 ratio, lower h/H ratio and lower concentration of desirable fatty acids in addition to a greater atherogenicity index (AI) and thrombogenicity index (TI).

Conclusion

Lambs of different sexes had carcasses with different quantitative traits without total influence on the chemical and physical meat characteristics. The lipid profile of the meat was less favorable to consumer health when the animals were female or submitted to 60% feed restriction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Farming ruminants has an unquestionable importance to the economic and food security of many regions of the world, especially for tropical semi-arid regions [1], where sheep are highly relevant [2, 3]. In these regions, the environment interferes intensely with productive management strategies, and making decisions is crucial for the success of animal husbandry.

Production systems in semi-arid regions are based on the use of genetic resources with high adaptability and heat tolerance, which are heavily influenced by the qualitative and quantitative seasonality of food, but these local breeds are now threatened with extinction. Morada Nova is a prominent genetic group of hair sheep in semiarid regions of Brazil. These sheep are an indigenous group used for the production of meat and skin. They are smaller, have lower mortality rates, produce lighter carcasses, and are usually late to slaughter. Adult Morada Nova hair sheep weigh between 45 and 50 kg and can reproduce at approximately 8–9 mons of age with approximately 28 kg of body weight (BW) [4].

The improvement of animal yield by enhancing sustainable biodiversity may be a pathway toward greater food supplies. Such sustainable increases may be especially important for the 2 billion people reliant on small farms, many of which are undernourished, yet we know little about the efficacy of this approach.

Some productive strategies affect animal performance as well as the chemical and physical quality of the meat produced. The farmer can, for example, opt to obtain production rates and carcasses with different characteristics depending on the sex of the animals [5,6,7]. In tropical semi-arid regions, animals can be submitted naturally to periods of feed restriction (FR) due to feed supply variations or due to feed management planning, which is commonly used to save resources and reduce costs [8, 9]. Under these conditions, it may be assumed that in addition to lower performance, meat products may have different chemical and physical characteristics if the animals are sold [10, 11].

In the face of global concerns about the safety and nutritional quality of foods, it is necessary to understand the effects of commonly used production strategies not only on productivity but also on aspects related to human health, as is the case with lipid quality parameters. Thus, we simulate the impact of feed restriction in hair sheep of different sexes in semi-arid regions. We then evaluate their effects on carcass characteristics, meat quality and fatty acid profiles in the meat of Morada Nova lambs.

Methods

Animal care and location

This study was conducted at the Department of Animal Science, Federal University of Ceará, located in Fortaleza, CE, Brazil. Protocols (n° 98/2015) were in accordance with the standards established by the Committee of Ethics in Animal Research of the Federal University of Ceará.

Animals, experimental design and management

Experimental lambs were obtained from the Morada Nova sheep breeding facility. The mating season was established with the objective of enabling a selection of animals with little variation in BW. Thirty-five lambs of the Morada Nova breed, including 23 males and 12 females, were selected. Twelve entire males were randomly assigned to the sexual class of castrated males, and the males were castrated using the burdizzo castrating method. Initially, the lambs had 14.5 ± 0.89 kg of BW and 120 d of age. The lambs were distributed in a completely randomized design in a 3 × 3 factorial scheme. Experimental treatments consisted of three sexes (11 entire males, 12 castrated males and 12 females) and three quantitative feeding levels (ad libitum (AL), 30% and 60% FR). The ration was formulated to supply the nutritional requirements of late maturity lambs with a gain of 150 g/d as recommended by the National Research Council (NRC) [12]. Before beginning data collection, the animals were randomly assigned to individual boxes provided with feed and water troughs, where they underwent an adaptive period of 15 d. Total mixed rations were provided twice a day (0730 and 1600 h), allowing for up to 10% orts only for animals fed AL. Before each morning feeding, the orts of each animal fed AL were removed and weighed to calculate the intake and feeding level of the lambs submitted to 30% and 60% FR (300 and 600 g/kg of FR). Thus, the restrictions were proportionally based on the intake of animals fed AL of each sex.

The ingredients used in the total ration and their proportions and composition are described in Table 1.

Samples of the roughage, concentrated and feed orts were taken to determine their chemical compositions and dry matter intake (DMI) of the lambs. The lambs were weighed every fifteen days to calculate BW gain (BWG). The trial period lasted 120 d. At the end of the trial period, the animals were weighed to determine total weight gain (TWG) and average daily gain (ADG).

Slaughter, carcass data and meat samples

After 18 h of fasting, the animals were weighed to determine their BW at slaughter (BWS). The animals were then skinned and eviscerated according to the rules established in the Regulation of Brazilian Industrial and Sanitary Inspection of Animal Products. Subsequently, the lambs were stunned with the proper equipment, bled, skinned, and eviscerated. The viscera were weighed when filled, emptied, washed, drained and weighed when empty to determine the contents of the gastrointestinal tract and subsequently the empty BW (EBW) of the animals. The carcasses were identified and weighed to obtain the hot carcass weight (HCW) and yield (HCY) calculated in relation to BWS. After 24 h of cooling at 4 °C, the carcasses were weighed to obtain the cold carcass weight (CCW). Twenty-four hours post mortem, the pH was measured using a pH meter (HI-99163, Hanna® instruments, São Paulo, Brazil) by inserting the meter between the 4th and 5th lumbar vertebrae in the longissimus lumborum muscle.

The carcasses were sectioned with an electric saw (Ki Junta®, São Paulo, Brazil) along the spine, and the left halves of the carcasses were divided into six commercial cuts (leg, loin, ribs, lower ribs, neck and shoulder), which were individually weighed. A cross-sectional cut was made between the 12th and 13th ribs to expose the longissimus thoracis (LT) muscle, which measured the maximum distances between the ends of the muscle in the mediolateral direction (A) and dorsal-ventral (B) to subsequently calculate the rib eye area (REA) according to Eq. REA = (A / 2 × B / 2) × π. Subcutaneous fat thickness (SFT) was verified above measure B using a digital caliper. Samples were taken from the LT and longissimus lumborum (LL) muscles, vacuum packed and stored at −20 °C.

Physicochemical meat analyses

The meat color was evaluated using a transverse cut on the back section, which was exposed to atmospheric air for 30 min before reading the oxygen myoglobin, which is the primary element that defines meat color [13]. As described by Miltenburg et al. [14], the coordinates L*, a* and b* were measured at three different points on the muscle, and the triplicates were averaged for each coordinate per animal. These measurements were performed using a Minolta CR-10 colorimeter (Konica® Minolta, Osaka, Japan) that was previously calibrated with the CIELAB system using a blank tile, illuminant D65 and 10° as the standard observation points. L* is related to lightness (L* = 0 black, 100 white); a* (redness) ranges from green (−) to red (+); and b*(yellowness) ranges from blue (−) to yellow (+). Measurements were made from a 2° viewing angle using illuminant C. The color saturation (chroma, C*) was calculated as (a*2 + b*2)1/2 [15].

Meat samples of LL muscle were processed in a crusher to determine the water holding capacity (WHC), and cooking weight loss (CWL) was determined according to the American Meat Science Association (AMSA) [16] using LL meat samples (triplicate) without visible connective tissue that were previously thawed at 10 °C for 12 h. CWL indicated the difference in the weight of the meat before and after cooking on a preheated grill (George Foreman Jumbo Grill GBZ6BW, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) at 170 °C. A digital skewer thermometer (Salcasterm 200®, São Paulo, Brazil) was used to monitor the internal temperature of the steak until the center reached 71 °C. Then, each steak was brought to room temperature, removed from the oven after temperature stabilization, and weighed again. The difference between the initial and final weights of a sample was used to determine the CWL, with the value expressed as a percentage.

After cooling at room temperature, the samples were again wrapped in foil and placed in a refrigerator (Consul CHB53C®, Salvador, Brazil) for 12 h at 4 °C. Fillets (5 ± 1) approximately 2 cm long, 1 cm wide and 1 cm high were cut from the meat to be evaluated for Warner-Bratzler shear force (WBSF). The instrumental texture analysis was performed on a TAXT2 texturometer (Stable Micro Systems Ltd., Vienna Court, UK) at 200 mm/min using standard shear blades (1.016 mm thick with a 3.05-mm blade). The instrumental texture analysis was performed according to the Research Center for Meat (US Meat Animal Research Center) and Shackelford et al. [17].

To evaluate lipid oxidation, meat samples of LL muscle stored under fast freezing at −20 °C for three months were thawed and crushed. Using the aqueous acid extraction method described by Cherian et al. [18], the 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) were measured in mg of malondialdehyde (MDA)/g of tissue.

Meat samples of LT muscle were evaluated for moisture, ash and protein contents, following method numbers 930.15, 920.153 and 928.08, respectively [19]. LT muscle samples were used to extract and quantify intramuscular fat (IMF). The fat of meat samples was isolated and purified using polar solvents (chloroform and methanol) according to the procedure of Folch et al. [20]. Aliquots of the fat extract were reserved and stored at −20 °C for subsequent use in determining the fatty acid profile.

Fatty acid profile

To determine the fatty acid profile, the fat samples previously extracted from LT muscle were converted to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). The FAMEs were prepared using a solution of methanol, ammonium chloride and sulfuric acid, following the procedure described by Hartman and Lago [21].

Samples were analyzed using a chromatograph (GC2010, Shimadzu®, São Paulo, Brazil) equipped with a flame-ionization detector and a biscyanopropyl polydimethylsiloxane capillary column of stationary phase (SP2560, 100 m × 0.25 mm, df 0.20 μm; Supelco®, Bellefonte, PA, USA). The column oven temperature was as follows: the initial temperature was held for 80 ° C, increased at 11 °C/min to 180 °C and at 5 °C/min to 220 °C and then maintained for 19 min. Hydrogen was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min, the split ratio was 1:30, and the injector and detector temperatures were 220 °C. The FAMEs were identified by a comparison of the FAME retention times with those of authentic standards (FAME mix components, Supelco®, Bellefont, PA, USA) following the same injection method. The results were quantified by normalizing the areas of the methyl esters and converted to mg/100 g of meat using a conversion factor of 0.92 for the contribution of fatty acids in lipids [22].

The concentrations of saturated fatty acids (SFAs), unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), ω6 and ω3 were calculated based on the fatty acid profile of the meat. Lipid quality indexes were determined using the sum of the desirable fatty acids [23], the thrombogenicity index (TI), the atherogenicity index (AI) [24], and the ratio between fatty acids hypocholesterolemic acid and hypercholesterolemic acid (h/H) [25]. The activity of enzymes involved in lipid metabolism, such as Δ9 desaturase in C16, Δ9 desaturase in C18 and elongase, were calculated according to the methods of Malau-Aduli et al. [26].

Feed chemical analysis

To determine the chemical composition of the feed, triplicate samples were dried at 55 °C for 72 h in a forced-air oven, ground with a Willey mill (Tecnal®, São Paulo, Brazil) with a 1-mm sieve, and stored in airtight plastic containers (ASS®, São Paulo, Brazil). The samples were then stored in plastic jars with lids (ASS®, São Paulo, Brazil), labeled, and subjected to further laboratory analysis to measure the contents of dry matter (DM method 967.03), ash (method 942.05), crude protein (CP method 981.10), and ether extract (EE method 920.29) according to the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) [27].

The neutral detergent fiber (NDF) content was determined as described by Van Soest et al. [28]. The acid detergent fiber (ADF) contents were determined as described by Robertson and Van Soest [29]. The NDF residue was incinerated in an oven at 600 °C for 4 h to determine the ash content, and the protein concentration was calculated by subtracting the neutral detergent insoluble protein (NDIP). NDF was corrected for the ash and protein contents. The Non-fiber carbohydrate (NFC) content was measured according to Mertens [30] and calculated based on the differences in the equation NFC = 100 – NDF – CP – EE – ash.

Statistical analyses

Variables were subjected to analysis of variance using the GLM procedure of Statistical Analysis System - SAS® software [31] and the following equation: Yijk = μ + Si + Rj + Si × Rj + εijk, where Yijk is the dependent or response variable measured in the animal or experimental unit “k” of sexual class “i” at FR “j”; μ is the population mean or global constant; Si is the effect of sexual class “i”; Rj is the effect of FR “j”; Si × Rj is the interaction between effects of sexual class “i” and FR “j”; and ɛijk is unobserved random error. Tukey-Kramer’s test was used to compare the means with a significance level of 5% probability (P < 0.05), and the same criterion was adopted for interactions between the effects of sex and FR.

Results

Performance and carcass traits

There was an interaction (P < 0.05) between sex and FR for ADG, BWS and EBW (Table 2). In sum, females subjected to AL intake presented similar ADG, BWS and EBW (P > 0.05) to those of entire males and castrated males fed 30% FR (Table 3). Entire males fed AL presented higher (P < 0.05) ADG, BWS and EBW due to their higher growth (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Evolution of animal weights during the experimental period. Average animal weight (kg) of each treatment in relation to approximate age in days from the beginning (120 d) to the end of the experiment (240 d); Ent AL = Entire males subjected to ad libitum intake; Cas AL = Castrated males subjected to ad libitum intake; Fem AL = Females subjected to ad libitum intake; Ent 30 = Entire males subjected to 30% feed restriction; Cas 30 = Castrated males subjected to 30% feed restriction; Fem 30 = Females subjected to 30% feed restriction; Ent 60 = Entire males subjected to 60% feed restriction; Cas 60 = Castrated males subjected to 60% feed restriction; Fem 60 = Females subjected to 60% feed restriction

Except for SFT, the carcass traits that were analyzed (HCW, HCY, CCW, CCY and REA) were influenced (P < 0.05) by sex (Table 4). Entire males showed higher means of HCW and CCW followed by castrated males and females. However, females and castrated males had a higher HCY than did entire males. After cooling and considering the losses caused by this process, only females had the highest yield (CCY), whereas castrated males did not differ from the other sexes. The level of FR did not influence (P > 0.05) the HCY and CCY, which indicated that the lower weights due to lower feed intake occurred proportionately throughout the bodies of the animals. HCW, CCW and SFT decreased with increasing FR (60%).

There was an interaction (P < 0.05) between sex and FR in neck weight (Table 4). However, no clear result was evidenced (Table 5). The weights of all commercial cuts were influenced (P < 0.05) by sex and by FR (Table 4). Entire males had heavier cuts, followed by castrated males and females, which reflected the effects observed with the CCW. The weights of the commercial cuts decreased due to the reduction in feeding supply.

Physicochemical meat quality

L* was influenced (P < 0.05) by sex (Table 6). The color parameters a*, b* and C* were not affected by sex or FR. Castrated males and females did not differ (P > 0.05), and they had lower values (P < 0.05) than did entire males. Animals subjected to 60% FR showed a higher 24 h post-mortem pH in their meat compared to that of animals subjected to AL intake.

There was no effect (P > 0.05) of FR and sex on the protein content in meat from LT muscle (Table 6). However, an interaction (P < 0.05) between sex and FR for this variable was observed. Females fed AL had a higher (P < 0.05) protein content than did females submitted to 30% FR (Table 7). The moisture content in the LT muscle of animals with AL intake was lower (P < 0.05) compared to that of animals subjected to 30 and 60% FR (Table 6). Animals submitted to AL intake and 30% FR provided similar (P > 0.05) amounts of IMF, whereas animals subjected to 60% FR had a reduced (P < 0.05) concentration of IMF. Ash percentage was higher (P < 0.05) in the meat from animals subjected to 60% FR.

Fatty acid profile

It was not possible to separate the peaks of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) isomers normally identified in meats from ruminants. Thus, the nomenclature used covered all isomers (CLA). There was an interaction (P < 0.05) between sex and FR for elaidic acid (C18:1 t9) and behenic acid (C22:0) in the meat of the LT muscle (Table 8). However, after adjusting for multiple comparisons, a clear interaction response was only detected for elaidic acid (Table 9). Probably data set characteristics contributed to the absence of significance after the Tukey-Kramer test, contradicting the initial result of the ANOVA for the behenic acid. Females submitted to 60% FR had higher amounts of elaidic acid than did entire males and castrated males submitted to 60% FR (Table 9).

There was an effect (P < 0.05) of sex only on the concentrations of linoleic acid (C18:2 c9c12) and arachidonic acid (C20:4 c5c8c11c14) (Table 8). Females showed higher (P < 0.05) concentrations of these fatty acids than did entire males and castrated males, which showed no difference (P > 0.05) compared to the other categories. Meat of animals submitted to AL intake and 30% FR showed similar (P > 0.05) and higher (P < 0.05) values compared to those of animals subjected to 60% FR for concentrations of palmitic acid (C16:0), palmitoleic acid (C16:1c9), stearic acid (C18:0), oleic acid (C18:1c9) and CLA. The concentration of myristic acid (C14:0) was higher (P < 0.05) in meat from animals subjected to 30% FR than in meat from animals subjected to 60% FR. Meat from animals subjected to 60% FR showed greater (P < 0.05) concentrations of arachidonic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5c5c8c11c14c17 - EPA) than did meat from animals subjected to AL intake and 30% FR.

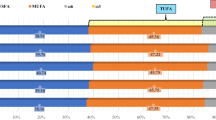

The concentration of PUFAs was greater in the meat of females and lower in the meat of entire males (Table 10). However, the meat of females provided a higher ω6/ω3 ratio and AI in addition to presenting a lower h/H ratio. The activity of the elongase enzyme was higher in the LT muscle of castrated males. The sum of SFA, UFA and PUFA was similar (P > 0.05) in the meat of animals subjected to AL intake and 30% FR and was higher (P < 0.05) compared to that in animals subjected to 60% FR. The meat of animals subjected to 60% FR provided a greater ω6/ω3 ratio, lower h/H ratio and lower concentration of desirable fatty acids, in addition to a greater AI and TI.

Discussion

Performance, carcass traits and physicochemical meat quality

Productions systems in semi-arid regions are based on the use of genetic resources with high adaptability and heat tolerance, which are heavily influenced by qualitative and quantitative seasonality of food [32, 33]. An example is the Morada Nova, an important indigenous breed of hair sheep in northeastern Brazil that is used for meat and skin production and is highly valued on the international market [34]. Weight loss has a strong impact on animal productivity [35], compromising the animal welfare and income of farmers worldwide [33]. In our study, we observed an absence of growth in females with 60% FR and a low ADG in lambs with 30% FR. This effect is a response to a lower amount of nutrients [36] because lambs have higher energy and protein requirements for growth [32, 37], which demand higher intakes. The study of van Harten et al. [38] showed that in animals under FR, lipids are mobilized and transformed into energy. This occurs to meet the net energy requirements for maintenance. In addition to genetic and nutritional factors, sex is variable and impacts animal productive responses.

Effects of interactions between sex and FR showed that females performed similarly to entire males and castrated males with 30% FR. Such effects reflect the empty cup weight gain, when females generally present lower rates of protein deposition in the empty body [39].

A sex effect is evident in the regulation of adiposity and muscularity and has been attributed to sexual steroid hormones [40] because testosterone promotes an increase in body mass [41]. These effects were observed in this study, in which entire males had higher carcass weights and commercial cuts. Castrated males [6] and females [42] present higher HCY attributed to increased fat deposit during weight gain [43]. Furthermore, the higher central or intra-abdominal accumulation of fat in male individuals [44] contributed to greater proportions of non-carcass components and consequently had a lower carcass yield.

Dietary restrictions have reduced the accumulation of the body stores of fat and protein, which resulted in lighter carcasses and commercial cuts. Nutritional limitations reduce cell proliferation and differentiation in tissues in response to reduced local production of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), as signaled by the state of relative resistance of growth hormone (GH) [45]. In addition, in the post-absorptive state, non-esterified fatty acids, glycerol, alanine and glycine are oxidized, which supplies part of the energy demand [46]. Thus, in situations of lower nutritional intake, some of the body energy reserves are consumed. This situation was observed in animals submitted to the levels of FR used in this research.

The 24 h post-mortem pH was higher in the meat from animals subjected to 60% FR, which may be related to the lower content of muscle glycogen caused by lower feed intake and intense mobilization of reserves during the development of these animals. However, the pH remained between 5.5 and 5.8, which is desirable for meat [47]. An increase in the pH of meat can increase the activity of cytochrome oxidase by reducing the uptake of oxygen by myoglobin, which results in a purplish red color [48]. However, the higher pH in meat from animals subjected to 60% FR was not enough to influence the color and other quality parameters analyzed in this study.

L* was greatly influenced by the pigment contents, especially those of hematin, myoglobin and their forms [49]. Chromophores, such as myoglobin and hemoglobin, absorb visible light by increasing light penetration and consequently decreasing reflectance [50]. Sañudo et al. [51] observed more myoglobin in females (2.90 mg/g of meat) than in entire males (2.56 mg/g of meat) and reported a similar effect of sex on L*, recording 39.80% for females and 41.26% for entire males. More myoglobin may explain the color variation in the meat of female animals observed in the present study.

Testosterone, besides providing an anabolic effect [41], acts on plasma glucose levels in males but does not alter the phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase in muscle [40], which influences the concentration of IMF in males to a small degree. A similar result was observed in this study because the percentage of meat fat was similar between the sexes and did not reflect the effects of higher HCW in entire males.

Variations in meat fat concentration occur mainly due to changes in balance between dietary energy and nutrient requirements [52]; thus, the least amount of energy consumed by animals subjected to 60% FR decreased the deposition of IMF. FR of 60% meets the net energy needs for maintenance and obviously does not prioritize nutrients for the deposition of adipose tissue. However, 30% FR did not cause significant changes to this balance or to the concentration of IMF in LT muscle.

Fatty acid profiles

Studies on cattle have indicated increased incorporation of long chain fatty acids into the phospholipids of heifer meat in response to concentrations of plasmalogens [53]. The effects observed on the concentration of linoleic and arachidonic acids in meat of females indicate that this incorporation can also occur in lamb meat but was not observed due to the need for a more detailed analysis. The effect of the interaction between sex and FR on elaidic acid concentration shows that under 60% FR, females accumulate a greater amount of this acid. It becomes important to know the unique physiological functions of specific isomers as well as their origin. A portion of the trans-11 C18:1 isomer produced by ruminal microbes is converted into cis-9, trans-11 C18: 2 by tissue desaturase [54]; however, this cannot occur with elaidic acid (C18:1 t9). The quality lipid indexes showed that the meat of female animals had a lipid profile with less desirable characteristics compared to that of meat from other sexes due to a higher AI and a lower h/H ratio. The higher ω6/ω3 ratio would also indicate lower quality meat fat in females [55]; however, the latest recommendations suggest no rational limit for this ratio if the intake of ω6 and ω3 is within the proper range for human diets [56].

More feeding can explain the higher concentration of palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, stearic acid and oleic acid in the meat of animals subjected to AL intake and 30% FR. These effects reflect the results observed with the IMF content. As 30% FR did not significantly influence the deposition of IMF, there was no effect on the composition of fatty acids. The kinetics of the feed in the rumen may also have influenced the exposure time of the fatty acids to biohydrogenation [57]. The more severe restriction may have resulted in a lower passage rate, higher biohydrogenation, and higher deposition of SFA. Furthermore, the incorporation of fatty acids synthesized in muscle tissue may have been more effective in animals subjected to AL intake and 30% FR. This is related to a more lipogenic substrate for de novo synthesis in muscle adipocytes [58, 59], especially glucose from the propionate originating from the fermentation of carbohydrates in the rumen [60].

In our study, the lowest IMF deposit was in the meat of animals subjected to 60% FR, which justified the lower concentration of CLA in meat, as CLA is preferentially deposited in triglycerides [61, 62]. Similarly, the lowest IMF deposits in the meat of animals subjected to 60% FR may explain the higher concentration of long chain PUFAs (EPA and AA) in meat, which are deposited primarily in phospholipids [63, 64]. The IMF consists of triglycerides deposited in adipocytes and myofibril cytoplasm droplets, structural phospholipids and cholesterol present in membranes [58]. Triglycerides are more mobile, and phospholipids are more stable in muscle [65].

Based on the results of this study, lambs subjected to 60% FR can be expected to produce meat with fatty acid concentrations that are less favorable to consumer health and with a lower amount of desirable fatty acids, a lower h/H ratio, a higher AI and TI and a higher proportion of SFA (55.3%) compared to those of animals submitted to AL intake (48.3%) and 30% FR (49.2%). A lipid profile favorable to the thrombogenicity and atherogenicity in the meat of animals subjected to 60% FR is related to myristic acid, palmitic acid and stearic acid concentrations [24]. Values from 0.9 to 1.94 for TI and 0.59 to 1.15 for AI have been reported in the literature [66,67,68,69]; the maximum values of TI (1.93) and AI (0.87) found in this study were within this range.

The activity of the elongase enzyme is related to concentrations of palmitic, palmitoleic and oleic acids [11, 70]. Combined concentrations of these fatty acids resulted in increased activity of elongase in the muscle of castrated male animals. The lower activity of the Δ9 desaturase enzyme C18 in animals subjected to 60% FR could be attributed to lower amounts of oleic acid present in the muscle of these animals [71].

Conclusions

Lambs in different sexes produced carcasses with different characteristics, and except for lightness, sex did not influence meat quality or chemical composition. However, females had a fatty acid profile in their meat that was less favorable to consumer health. FR affected carcass traits without influencing the quality of the meat. IMF content decreased when animals were subjected to 60% FR, but the lipid profile was less favorable to consumer health.

Abbreviations

- a*:

-

Redness

- ADF:

-

Acid detergent fiber

- ADG:

-

Average daily gain

- AI:

-

Atherogenicity index

- AL:

-

Ad libitum

- b*:

-

Yellowness

- BW:

-

Body weight

- BWS:

-

Body weight at slaughter

- C*:

-

Chroma

- CCW:

-

Cold carcass weight

- CCY:

-

Cold carcass yield

- CP:

-

Crude protein

- CWL:

-

Cooking weight losses

- DFA:

-

Desirable fatty acids

- DM:

-

Dry matter

- DMI:

-

Dry matter intake

- EBW:

-

Empty body weight

- EE:

-

Ether extract

- FR:

-

Feed restriction

- HCW:

-

Hot carcass weight

- HCY:

-

Hot carcass yield

- IBW:

-

Initial body weight

- L*:

-

Lightness

- LL :

-

longissimus lumborum

- LT :

-

longissimus thoracis

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- MUFA:

-

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- NDF:

-

Neutral detergent fiber

- NFC:

-

Non-fiber carbohydrate

- NRC:

-

National research council

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- REA:

-

Rib eye area

- SAS:

-

Statistical analysis software

- SFA:

-

Saturated fatty acid

- SFT:

-

Subcutaneous fat thickness

- TBARS:

-

2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- TI:

-

Thrombogenicity index

- TWG:

-

Total weight gain

- UFA:

-

Unsaturated fatty acid

- WHC:

-

Water holding capacity

- ω3:

-

Omega 3

- ω6:

-

Omega 6

References

Mlambo V, Mapiye C. Towards household food and nutrition security in semi-arid areas: What role for condensed tannin-rich ruminant feedstuffs? Food Res. 2015;76:953–61. Int. Elsevier Ltd.

Toro-Mujica P, Aguilar C, Vera R, Rivas J, García A. Sheep production systems in the semi-arid zone: Changes and simulated bio-economic performances in a case study in Central Chile. Livest Sci. 2015;180:209–19. Elsevier.

Selvaggi M, Laudadio V, Dario C, Tufarelli V. Investigating the genetic polymorphism of sheep milk proteins: a useful tool for dairy production. J Sci Food Agric. 2014;94:3090–9.

Pereira ES, Carmo ABR, Costa MRGF, Medeiros AN, Oliveira RL, Pinto AP, et al. Mineral requirements of hair sheep in tropical climates. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2016;100:1090–6.

Craigie CR, Lambe NR, Richardson RI, Haresign W, Maltin CA, Rehfeldt C, et al. The effect of sex on some carcass and meat quality traits in Texel ewe and ram lambs. Anim Prod Sci. 2012;52:601–7.

Sales J. Quantification of the effects of castration on carcass and meat quality of sheep by meta-analysis. Meat Sci. 2014;98:858–68. Elsevier Ltd.

Hopkins DL, Mortimer SI. Effect of genotype, gender and age on sheep meat quality and a case study illustrating integration of knowledge. Meat Sci. 2014;98:544–55. Elsevier B.V.

Neto SG, Bezerra LR, Medeiros AN, Ferreira MA, Filho ECP, Cândido EP, et al. Feed Restriction and Compensatory Growth in Guzerá Females. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2011;24:791–9.

Bezerra LR, Neto SG, de Medeiros AN, Mariz TM de A, Oliveira RL, Cândido EP, et al. Feed restriction followed by realimentation in prepubescent Zebu females. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2013;45:1161–9.

Madruga MS, Torres TS, Carvalho FF, Queiroga RC, Narain N, Garrutti D, et al. Meat quality of Moxotó and Canindé goats as affected by two levels of feeding. Meat Sci. 2008;80:1019–23.

Lopes LS, Martins SR, Chizzotti ML, Busato KC, Oliveira IM, Machado Neto OR, et al. Meat quality and fatty acid profile of Brazilian goats subjected to different nutritional treatments. Meat Sci. 2014;97:602–8. Elsevier Ltd.

NRC. Nutrient Requirement of Small Ruminants. Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2007.

Cañeque V, Sañudo C. Metodología para el estudio de la calidad de la canal y de la carne en rumiantes. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnologia y Alimenticia; 2001.

Miltenburg GA, Wensing T, Smulders FJ, Breukink HJ. Relationship between blood hemoglobin, plasma and tissue iron, muscle heme pigment, and carcass color of veal. J Anim Sci. 1992;70:2766–72.

MacDougall DB, Taylor AA. Colour retention in fresh meat stored in oxygen-a commercial scale trial. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2007;10:339–47.

AMSA. Guidlines for cooking and sensory evaluation of meat. Chicago: American Meat Science Association. National livestock and meat board; 1978.

Shackelford SD, Wheeler TL, Koohmaraie M. Evaluation of slice shear force as an objective method of assessing beef longissimus tenderness. J Anim Sci. 1999;77:2693.

Cherian G, Selvaraj RK, Goeger MP, Stitt PA. Muscle fatty acid composition and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances of broilers fed different cultivars of sorghum. Poult Sci. 2002;81:1415–20.

AOAC. Official Analytical Methods of Analysis. 17th ed. Washington: Association of Official Agricultural Chemists; 2002.

Folch J, Lees M, Stanley G. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509.

Hartman L, Lago RC. Rapid preparation of fatty acid methyl esters from lipids. Lab Pract London. 1973;22:475–6.

Weihrauch JL, Posati LP, Anderson BA, Exler J. Lipid conversion factors for calculating fatty acid contents of foods. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1977;54:36–40.

Rhee KS. Fatty acids in meats and meat products. In: Chow CK, editor. Fat. Acids Foods Their Heal. Implic. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2000.

Ulbricht TL, Southgate DA. Coronary heart disease: seven dietary factors. Lancet. 1991;338:985–92.

Santos-Silva J, Bessa RJ, Santos-Silva F. Effect of genotype, feeding system and slaughter weight on the quality of light lambs. Livest Prod Sci. 2002;77:187–94.

Malau-Aduli AEO, Siebert BD, Bottema CDK, Pitchford WS. A comparison of the fatty acid composition of triacylglycerols in adipose tissue from Limousin and Jersey cattle. Aust J Agric Res. 1997;48:715.

AOAC. Official methods of analysis. 15th ed. Washington: Association of Official Agricultural Chemists; 1990.

Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J Dairy Sci. 1991;74:3583–97.

Robertson JB, Van Soest PJ. The detergent system of analysis and its application to human foods. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1981. p. 123. Anal. Diet. fiber food.

Mertens DR. Creating a System for Meeting the Fiber Requirements of Dairy Cows. J Dairy Sci. 1997;80:1463–81.

Sas I. SAS User’s Guide: Basics. Cary: SAS Inst. Inc.; 2008.

Costa MRGF, Pereira ES, Silva AMA, Paulino PVR, Mizubuti IY, Pimentel PG, et al. Body composition and net energy and protein requirements of Morada Nova lambs. Small Ruminant Res. 2013;114:206–13. Elsevier B.V.

Cardoso LA, Almeida AM de. Seasonal weight loss-an assessment of losses and implications for animal welfare and production in the tropics: Southern Africa and Western Australia as case studies. Enhancing Anim. Welf. farmer income through Strateg. Anim. Feed. Some case Stud. Rome (Italy): FAO, Rome (Italy), Animal Production and Health Division; 2013. p. 37–44

McManus C, Paiva SR, De Araújo RO. Genetics and breeding of sheep in Brazil. Rev Bras Zootec. 2010;39:236–46.

Scanlon TT, Almeida AM, van Burgel A, Kilminster T, Milton J, Greeff JC, et al. Live weight parameters and feed intake in Dorper, Damara and Australian Merino lambs exposed to restricted feeding. Small Ruminant Res. 2013;109:101–6. Elsevier B.V.

Almeida AM, Schwalbach LM, De Waal HO, Greyling JPC, Cardoso LA. The effect of supplementation on productive performance of Boer goat bucks fed winter veld hay. Tropl Anim Health Prod. 2006;38:443–9.

Pereira ES, Fontenele RM, Silva AMA, Oliveira RL, Ferreira MRG, Mizubuti IY, et al. Body composition and net energy requirements of Brazilian Somali lambs. Ital J Anim Sci. 2014;13:880–6.

van Harten S, Kilminster T, Scanlon T, Milton J, Oldham C, Greeff J, et al. Fatty acid composition of the ovine longissimus dorsi muscle: effect of feed restriction in three breeds of different origin. J Sci Food Agric. 2015;96:1777–82.

Almeida AK, Resende KT, Tedeschi LO, Fernandes MHMR, Regadas Filho JGL, Teixeira IAMA. Using body composition to determine weight at maturity of male and female Saanen goats. J Anim Sci. 2016;94:2564.

Clarke SD, Clarke IJ, Rao A, Cowley MA, Henry BA. Sex Differences in the Metabolic Effects of Testosterone in Sheep. Endocrinology. 2012;153:123–31.

Kelly DM, Jones TH. Testosterone: a metabolic hormone in health and disease. J Endocrinol. 2013;217:R25–45.

Santos VAC, Cabo A, Raposo P, Silva JA, Azevedo JMT, Silva SR. The effect of carcass weight and sex on carcass composition and meat quality of “Cordeiro Mirandês”—Protected designation of origin lambs. Small Rumin Res. 2015;130:136–40. Elsevier B.V.

Nurnberg K, Wegner J, Ender K. Factors influencing fat composition in muscle and adipose tissue of farm animals. Livest Prod Sci. 1998;56:145–56.

Shi H, Clegg DJ. Sex differences in the regulation of body weight. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:199–204. Elsevier Inc.

Breier BH, Gluckman PD. The regulation of postnatal growth: nutritional influences on endocrine pathways and function of the somatotrophic axis. Livest Prod Sci. 1991;27:77–94.

Kozloski GV. Bioquímica dos Ruminantes. Santa Maria: UFSM; 2002.

Hedrick HB, Aberle ED, Forrest JC, Judge MD, R.A. M. Principles of Meat Science. 3rd ed. Yowa: Kendall and Hunt; 1994

Osório JCDS, Osório MTM, Sañudo C. Características sensoriais da carne ovina. Rev Bras Zootec. 2009;38:292–300.

Lindahl G, Lundström K, Tornberg E. Contribution of pigment content, myoglobin forms and internal reflectance to the colour of pork loin and ham from pure breed pigs. Meat Sci. 2001;59:141–51.

Krzywicki K. Assessment of relative content of myoglobin, oxymyoglobin and metmyoglobin at the surface of beef. Meat Sci. 1979;3:1–10.

Sañudo C, Sierra I, Olleta JL, Martin L, Campo MM, Santolaria P, et al. Influence of weaning on carcass quality fatty acid composition and meat quality in intensive lamb production systems. Anim Sci. 1998;66:175–88.

Geay Y, Bauchart D, Hocquette J-F, Culioli J. Effect of nutritional factors on biochemical, structural and metabolic characteristics of muscles in ruminants, consequences on dietetic value and sensorial qualities of meat. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2001;41:1–26.

Bessa RJB, Alves SP, Santos-Silva J. Constraints and potentials for the nutritional modulation of the fatty acid composition of ruminant meat. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2015;117:1325–44.

Santora JE, Palmquist DL, Roehrig KL. Trans-vaccenic acid is desaturated to conjugated linoleic acid in mice. J Nutr. 2000;130:208–15.

Wood JD, Richardson R, Nute G, Fisher A, Campo M, Kasapidou E, et al. Effects of fatty acids on meat quality: a review. Meat Sci. 2003;66:21–32.

FAO. Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition. Report of an expert consultation. Rome: Food and agriculture organization of the united nations; 2010. FAO Food Nutr. Pap.

Harvatine KJ, Allen MS. Fat supplements affect fractional rates of ruminal fatty acid biohydrogenation and passage in dairy cows. J Nutr. 2006;136:677–85.

Hocquette JF, Gondret F, Baéza E, Médale F, Jurie C, Pethick DW. Intramuscular fat content in meat-producing animals: development, genetic and nutritional control, and identification of putative markers. Animal. 2010;4:303–19.

Alves SP, Bessa RJB, Quaresma MAG, Kilminster T, Scanlon T, Oldham C, et al. Does the Fat Tailed Damara Ovine Breed Have a Distinct Lipid Metabolism Leading to a High Concentration of Branched Chain Fatty Acids in Tissues? Schunck W-H, editor. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77313

Smith SB, Kawachi H, Choi CB, Choi CW, Wu G, Sawyer JE. Cellular regulation of bovine intramuscular adipose tissue development and composition. J Anim Sci. 2009;87:E72–82.

Noci F, French P, Monahan FJ, Moloney AP. The fatty acid composition of muscle fat and subcutaneous adipose tissue of grazing heifers supplemented with plant oil-enriched concentrates. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:1062.

Costa ASH, Silva MP, Alfaia CPM, Pires VMR, Fontes CMGA, Bessa RJB, et al. Genetic Background and Diet Impact Beef Fatty Acid Composition and Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase mRNA Expression. Lipids. 2013;48:369–81.

Noci F, Monahan FJ, French P, Moloney AP. The fatty acid composition of muscle fat and subcutaneous adipose tissue of pasture-fed beef heifers: Influence of the duration of grazing. J Anim Sci. 2005;83:1167–78.

Wood JD, Enser M, Fisher AV, Nute GR, Sheard PR, Richardson RI, et al. Fat deposition, fatty acid composition and meat quality: A review. Meat Sci. 2008;78:343–58.

Raes K, De Smet S, Demeyer D. Effect of dietary fatty acids on incorporation of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acid in lamb, beef and pork meat: a review. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2004;113:199–221.

Komprda T, Kuchtík J, Jarošová A, Dračková E, Zemánek L, Filipčík B. Meat quality characteristics of lambs of three organically raised breeds. Meat Sci. 2012;91:499–505.

Lestingi A, Facciolongo AM, Marzo DD, Nicastro F, Toteda F. The use of faba bean and sweet lupin seeds in fattening lamb feed. 2. Effects on meat quality and fatty acid composition. Small Ruminant Res. 2015;131:2–5. Elsevier B.V.

Liu J, Guo J, Wang F, Yue Y, Zhang W, Feng R, et al. Carcass and meat quality characteristics of Oula lambs in China. Small Ruminant Res. 2015;123:251–9. Elsevier B.V.

Laudadio V, Tufarelli V. Influence of substituting dietary soybean meal for dehulled-micronized lupin (Lupinus albus cv. Multitalia) on early phase laying hens production and egg quality. Livest Sci. 2011;140:184–8. Elsevier B.V.

Fiorentini G, Lage JF, Carvalho IPC, Messana JD, Canesin RC, Reis RA, et al. Lipid sources with different fatty acid profile alters the fatty acid profile and quality of beef from confined Nellore steers. Asian Australas J Anim Sci. 2015;28:976–86.

Oliveira DM, Ladeira MM, Chizzotti ML, Machado Neto OR, Ramos EM, Goncalves TM, et al. Fatty acid profile and qualitative characteristics of meat from zebu steers fed with different oilseeds. J Anim Sci. 2011;89:2546–55.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq-Brazil).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

TA and ES conceived the study and conducted statistical analysis. TA, ES, AC and MP conducted the laboratory analyses and prepared the manuscript. ES, AC and EH managed the animal model and assisted with manuscript preparation. IM and EH assisted with diet formulation, statistical analysis and manuscript preparation. HM contributed to fatty acid analysis. LB and RO critically revised the manuscript and edited the language. LP contributed to conception and statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The experimental protocol used in this study, including animal management, housing, and slaughter procedures, was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Federal University of Ceara, Brazil (Protocol n°98/2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

de Araújo, T.L.A.C., Pereira, E.S., Mizubuti, I.Y. et al. Effects of quantitative feed restriction and sex on carcass traits, meat quality and meat lipid profile of Morada Nova lambs. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 8, 46 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-017-0175-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-017-0175-3