Abstract

Background

Human brown adipose tissue (BAT) activity is associated with lower body fatness and favorable glucose metabolism. Previous studies reported that oral fructose loading induces postprandial fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) secretion. FGF21 is a known inducer of adipose tissue thermogenesis; however, the effects of diet-induced FGF21 secretion on BAT thermogenesis remain to be elucidated.

Methods

The effects of both single load and daily consumption of fructose on BAT activity were examined using a randomized cross-over trial and a 2-week randomized controlled trial (RCT), respectively. In the cross-over trial, 15 young men consumed a single dose of fructose solution or water and then consumed the other on a subsequent day. The RCT enrolled 22 young men, and the participants were allocated to a group that consumed fructose and a group that consumed water daily for 2 weeks. BAT activity was analyzed using thermography with cold exposure. Plasma FGF21 level was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

In the cross-over single-load trial, plasma FGF21 levels were significantly increased at 2 h after oral fructose load (p < 0.01); however, there was no significant difference in BAT activity between the fructose load and drinking water. The 2-week RCT revealed that both plasma FGF21 levels and BAT activity were not significantly increased by daily fructose consumption compared to water. Correlation analyses revealed that BAT activity at the baseline and the final measurements were strongly and positively associated with the RCT (r = 0.869, p < 0.001). Changes in BAT activity were significantly and negatively correlated with changes in plasma glucose levels during the 2-week intervention (r = − 0.497, p = 0.022).

Conclusions

Oral fructose load induces a temporary increase in circulating FGF21 levels; however, this does not activate BAT thermogenesis in healthy young men. Further studies are needed to elucidate the effect of endogenous FGF21 on physiological function.

Trial registration

This study is registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network in Japan (number 000051761, registered 1 August 2023, retrospectively registered, https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000052680).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adipose tissues have different functional features. White adipose tissue is a regulator of energy storage and systemic metabolic homeostasis [1], whereas brown adipose tissue (BAT) converts metabolic energy into heat and thereby increases energy expenditure [2, 3]. In adult humans, the BAT depot is mainly localized in the supraclavicular region, and the heat production of BAT is activated by cold exposure [2, 3]. The cold-induced activation of BAT (BAT activity) induces energy expenditure and glucose disposal [4,5,6]. High levels of BAT activity are associated with lower body fatness [7, 8] and favorable glucose metabolism [9, 10]. Interventional studies reported that BAT activity was increased by oral intake of food ingredients such as capsinoids [4, 11] and tea catechins [12, 13]. Thus, BAT activity has health benefits, and the activity could be induced by environmental and/or nutritional factors.

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) is known as an endocrine and metabolic regulator that induces adipose tissue thermogenesis [14, 15]. FGF21 administration prevents body weight gain and the development of an insulin-resistant state in rodents [16]. Consistent results were shown in human studies, which reported that administration of FGF21 analogs decreased body weight and increased insulin sensitivity in people with type 2 diabetes [17, 18]. Other human studies suggested that blood FGF21 levels were significantly and positively associated with BAT activity [19, 20]. Therefore, endogenous secretion of FGF21 may have a physiological role in human energy metabolism. Recent studies reported that the secretion of FGF21 was stimulated by acute oral fructose load [21,22,23], which secreted hepatic FGF21 in a carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP)-dependent manner [24]. The results suggest that the FGF21 response to fructose intake may activate BAT thermogenesis. On the other hand, Richard et al. reported that a short-term high-fructose diet suppressed glucose uptake by cold-stimulated BAT in young men [25], suggesting the adverse effects of fructose consumption on BAT activity.

As the effects of diet-induced secretion of FGF21 on BAT thermogenesis activation remain to be elucidated, the present study aimed to evaluate the acute and short-term effects of fructose loading on BAT activity using a randomized cross-over trial and a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Methods

Ethics approval and trial registration

The present study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University (approval number 216). All participants provided written informed consent before enrolment. The study is registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network in Japan (number 000051761) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design and participants

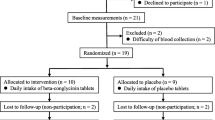

The effects of both single load and daily consumption of fructose on BAT activity were examined in the winter of 2022 (Fig. 1) by randomized cross-over trial and RCT, respectively. Participants were healthy young men aged over 18 years.

In the cross-over trial (Fig. 1A), 15 young men (aged 20–24 years) participated and were randomly divided into a group that received a single load of fructose (n = 9) and a group that received water (n = 6). The subjects switched to the other group after 3–7 days of the first dose. The data of one participant who did not complete the study was excluded; thus, the data of 14 participants were finally analyzed.

The RCT included 22 young men aged 18–24 years (Fig. 1B). The participants were randomized and allocated to a group that consumed fructose (n = 11) and a group that consumed water (n = 11). After baseline measurements, one participant in the group that consumed water declined to participate due to syncopal reaction after blood collection, and their data was excluded. The remaining 21 participants completed the 2-week intervention, and final measurements were performed.

Fructose intake

A fructose solution was prepared by dissolving 30 g of fructose in 225 mL of a commercial brand of water, as described in a previous study that examined a quantitative relationship between fructose load and FGF21 secretion [23]. The fructose solution was used in both the cross-over and controlled trials. A commercial brand of water was used as a control.

Measurement of BAT activity

BAT activity was determined using mild cold exposure, as described previously [20, 26]. In brief, subjects were seated at rest in a temperature-controlled room at 27 °C for 30 min. Baseline body surface temperature was measured using a thermal imaging camera (DETC1000T; D-eyes, Osaka, Japan). The subjects entered the climatic chamber (TBRR-9A4GX; ESPEC, Osaka, Japan), which was set at 19 °C. After the start of cold exposure, body surface temperature was collected at 30 min and 1 h of mild-cold exposure. Before and during cold exposure, subjects were asked to rate their shivering, cold sensation, and discomfort using a visual analog scale [20, 26].

The supraclavicular temperature adjacent to the BAT location on both the right and left sides was measured from each image. Chest temperature was simultaneously measured as a control for underlying BAT depots. The images of body surface temperature were analyzed using a modified (D-eyes) version of the Thermal-Cam v.1.1.0.9 software (Laon People, Seoul, Korea), and the average of supraclavicular temperature minus chest temperature was estimated as BAT activity. For the 2-week RCT, maximal BAT activity was defined as the higher BAT activity between 30 min and 1 h after cold exposure.

Anthropometric characteristics, dietary food intake, and physical activity

Body weight and body fat percentage were measured using an electronic scale (V-body HBF-359; Omron, Kyoto, Japan). Body mass index was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m). Energy, protein, carbohydrate, and fat intake were also assessed using a Food Frequency Questionnaire based on the food groups (Ver. 6.0; Kenpakusha, Tokyo, Japan) [27]. Physical activity was estimated by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire and expressed as metabolic equivalents per hour per week [28].

Measurements in the randomized cross-over trial and RCT

For all measurement days, subjects were instructed to arrive by 9:00 AM after an overnight fast, and the measurements were performed within 3 h.

In the cross-over trial (single load), baseline body surface temperature and blood sample were collected, and then the subjects consumed fructose solution or control water. The initiation of cold exposure was started 1.5 h after the oral fructose intake to match BAT thermogenesis [26] and a peak increase in blood FGF21 level 2 h after fructose load [21,22,23]. Body surface temperature and blood sample were collected at 30 min and 1 h of cold exposure (2 h and 2.5 h after the oral fructose load, respectively).

In the RCT (daily consumption), the same baseline and final measurements were performed before and after the 2-week daily consumption of fructose solution. Body surface temperature was measured at baseline (before cold exposure) and after 30 min and 1 h of cold exposure. Blood sampling was performed before cold exposure. The subjects did not consume fructose solution and could only consume water in the baseline and final measurements.

Blood analysis

The collected blood samples were centrifuged at 3000×g for 5 min. Plasma and serum were stored at – 80 °C until the time of analysis. The concentrations of plasma glucose and free fatty acid (FFA) were measured using Glucose C2-test Wako and NEFA C-test Wako (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan), respectively. Serum triglyceride, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol were determined by Kyoto Biken Laboratories, Inc. (Kyoto, Japan). Plasma FGF21 concentration was determined using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (DF2100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 29.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to assess the normality of data distribution. Two-way ANOVA analysis (time × condition) and post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test were used to determine the absolute value difference in the cross-over trial. Baseline characteristics and changes in variables during the RCT were compared using Student’s t test for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney U test for nonnormally distributed data. Relationships between changes in all variables were determined by Pearson’s correlation coefficients. All measurements and calculated values are presented as the mean ± SD, and the level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Effects of single fructose load on FGF21 and BAT in the cross-over trial

Subject characteristics for the cross-over single-load trial are shown in Table 1. Shivering response, cold sensation, and discomfort during cold exposure were not statistically different between the fructose load and drinking water conditions (data not shown). Compared to the baseline level, plasma FGF21 levels were significantly increased at 2 h after oral fructose load (p < 0.01), but decreased to non-significant levels at 2.5 h after loading (Fig. 2A). Plasma FGF21 levels at both 2 h and 2.5 h after drinking water were significantly lower than at the baseline level (p < 0.05). Plasma FFA levels were significantly decreased at both 2 h and 2.5 h after fructose loading (p < 0.05) in the group compared to the baseline level (Fig. 2B). There were no significant changes in plasma glucose levels during the single-load trial (Fig. 2C). As shown in Fig. 3, BAT activity, which was evaluated as standardized supraclavicular temperature, was significantly increased by 30-min and 1-h mild cold exposure at both 2 h and 2.5 h after fructose loading, respectively (p < 0.01). However, a significant increase in BAT activity was similarly observed after drinking water (p < 0.01). Two-way ANOVA analysis found that there was no significant difference in BAT activity between the fructose load and drinking water conditions (p = 0.923).

Changes in plasma FGF21, FFA, and glucose levels in the randomized cross-over trial. A Plasma FGF21 levels. B Plasma FFA levels. C Plasma glucose levels. Two-way ANOVA analysis and the post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test were performed. * and † indicate statistical significance compared to the baseline levels (p < 0.05). FGF21, fibroblast growth factor 21; FFA, free fatty acid

Effects of daily fructose consumption on FGF21 and BAT in the RCT

Table 2 shows anthropometric values, blood metabolic parameters, dietary consumption, physical activity, and BAT activity before and after the 2-week RCT. There were no significant changes in body weight and body fat percentage between the groups. The mean value of plasma glucose levels was reduced in the fructose group, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.173). Changes in blood lipid parameters were not different between the groups. Plasma FGF21 levels during the trial were increased both in the fructose and water groups, whereas the changes in the values between the groups were not significantly different in the RCT (p = 0.505). There was no difference in dietary consumption and physical activity between the groups. BAT activity at baseline and after cold exposure was not increased by daily fructose consumption and was not different between the fructose and water groups. For cold exposure, there was no significant difference in shivering response, cold sensation, and discomfort between the two groups (data not shown).

Associated factors of BAT activity in the RCT

Correlation analyses were performed to determine the associated factors of BAT activity changes during the 2-week intervention (Table 3). As shown in Fig. 4A, BAT activity at the baseline and the final measurements were strongly and positively correlated in the RCT (r = 0.869, p < 0.001). The changes in BAT activity during the trial were not associated with changes in plasma FGF21 levels (r = − 0.065, p = 0.780), whereas the changes in maximal BAT activity were significantly and negatively correlated with changes in plasma glucose levels during the 2-week intervention (Fig. 4B; r = −0.497, p = 0.022). Changes in anthropometric values, lipid metabolic parameters, dietary consumption, and physical activity were not associated with the changes in BAT activity.

Correlation analyses in the RCT. A Correlation of maximal BAT activity between the baseline and final measurements. B Correlation between changes in maximal BAT activity and plasma glucose levels. Open square shows the control group, and closed circle shows the fructose group. Results of Pearson’s correlation coefficients are shown. BAT, brown adipose tissue; RCT, randomized controlled trial

Discussion

We performed a randomized cross-over trial and an RCT to evaluate whether dietary-induced FGF21 secretion activates BAT thermogenesis. In the present study, oral fructose load increased plasma FGF21 levels more than 2-fold but did not influence BAT activity in both the acute and short-term interventions. The temporary increase in circulating FGF21 level may have little or no effect on BAT thermogenesis in young healthy adults.

The thermogenic action and mechanism of FGF21 have been explored using transgenic and high-dose models in rodents [16, 29], which showed abnormal levels of circulating FGF21. Because recombinant human FGF21 has a short half-life of less than 2 h in mice and primates [30], the pharmacological properties in clinical trials were examined using FGF21 analogs with a prolonged half-life [17, 18]. Unlike the above studies, the present study found that the increased FGF21 levels 2 h after oral fructose load were decreased within 30 min. Therefore, the weak and short actions of FGF21 were considered as the reason why the fructose intake did not activate BAT thermogenesis. It was reported that BAT activity is increased by methods of sympathetic nervous system activation such as cold exposure [5, 6] and oral intake of food ingredients [4, 11,12,13]. At this point, these methods have more advantages than FGF21 induction regarding BAT activation. Moreover, it was reported that a hypercaloric fructose diet was associated with risks of obesity [31] and fatty liver [32]. Both obesity and fatty liver accumulation are independent factors of chronic high FGF21 levels [33, 34], which is considered an FGF21-resistant state [35] and related to the onset of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [36,37,38,39]. Thus, the present study supports these previous studies that found that fructose intake has health disadvantages.

The present study found a dose-response relationship between 30 g oral fructose and blood FGF21 levels, which supports the findings of a previous study in the USA [23]. This suggests that genetic and lifestyle background do not affect oral fructose-induced FGF21 secretion and that the oral amount of fructose was adequate to increase circulating FGF21 levels. On the other hand, we found a significant decrease in plasma FGF21 levels after drinking water in the single-load trial. This finding may be explained by a diurnal rhythm of circulating FGF21, which decreases from morning to afternoon [40]. Daily fructose intake at breakfast may influence the diurnal rhythm of FGF21, although the physiological role requires further investigation. Circulating FFA levels were decreased around 2 h after oral fructose load as seen in this and a previous study [41]. Fructose consumption activates hepatic ChREBP [24], which induces triglyceride synthesis in the liver [42]. It is likely that hepatic FFA uptake increased due to lipogenesis, and a temporary decrease in FFA levels was observed. Previous studies reported that FGF21 administration induced glucose uptake in both adipocyte and adipose tissue [16, 43]; however, in the present study, a single load did not show changes in plasma glucose levels during increased plasma FGF21. Our findings suggest that an acute increase in endogenous FGF21 may not have an impact on whole glucose homeostasis in healthy young men.

The present study found that both anthropometric and blood metabolic parameters did not significantly change after 2 weeks of daily consumption of 30 g of fructose. Our findings suggest that short-term fructose consumption does not have both beneficial and adverse effects on the parameters of healthy young adults. Daily fructose consumption did not change baseline FGF21 levels; thus, daily FGF21 secretion may not modulate the diurnal rhythm of FGF21. Previous studies reported that resting levels of circulating FGF21 were increased by a low protein diet [44] and were decreased by endurance exercise [45, 46]. We assessed macronutrient intakes and physical activity using standardized questionnaires; however, these associated factors were unchanged between the baseline and final measurements. For the correlation analyses, a highly reproducible correlation was observed between the baseline and final measurements of BAT activity in the RCT. Our findings suggest that BAT activity was stable within individuals throughout the study period and was not influenced by the intervention. In addition, changes in glucose levels were only negatively associated with BAT activity in young men. The role in glucose disposal of activated BAT has been reported [4,5,6]; thus, unlike the consumption of fructose, changes, such as environmental and/or daily variation in BAT activity, may be associated with glucose disposal and negative correlation in the RCT.

Body temperature is controlled by shivering thermogenesis in skeletal muscle and non-shivering thermogenesis in BAT [47]. Cold-induced shivering is limited in neonates due to underdeveloped skeletal muscle. As a result, human neonates have various BAT sites including the interscapular, neck, and mediastinum regions [47]. Although BAT has a role in acclimatization to cold exposure after adolescence, the presence and volume of BAT decline with age [47]. The underlying factors of BAT adaptability are unclear. Previous studies reported that FGF21-deficient mice displayed an impaired response to cold stress [48], and the diurnal reduction of FGF21 was suppressed by cold exposure in healthy adults [49, 50]. Thus, FGF21 may be a mediator of cold-induced thermogenesis in adults; however, the present study did not find either the suppressed FGF21 reduction by cold exposure or the association of plasma FGF21 level with BAT activity in young men. Because female subjects participated in these previous studies [49, 50], our findings may be partly explained by sex differences in FGF21 responsiveness and/or BAT thermogenesis in cold adaptation.

This study has several limitations. The sample size was relatively small. Blinding was not performed because fructose has a sweet taste. Young healthy subjects participated; therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to other age categories and patients with metabolic diseases. BAT activity was not assessed by positron emission tomography-computerized tomography, which is the gold standard method for evaluating BAT [2]. In the cross-over trial, cold-induced changes in diurnal FGF21 rhythm should be considered [49, 50]. Although dietary-induced FGF21 secretion could not activate BAT, the effects of longer FGF21 action, such as using an FGF21 analog, on thermogenesis were unclear. Further clinical research is necessary to explore the physiological role of FGF21 in human BAT.

Conclusions

Oral fructose load induces a temporary increase in circulating FGF21 levels; however, the increased FGF21 does not activate BAT thermogenesis in healthy young men. Although it tends to evaluate the increase and/or decrease levels in the hormone, the implications of endogenous FGF21 on physiological function require further exploration.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BAT:

-

Brown adipose tissue

- ChREBP:

-

Carbohydrate response element binding protein

- FGF21:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 21

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Trayhurn P, Beattie JH. Physiological role of adipose tissue: white adipose tissue as an endocrine and secretory organ. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001;60(3):329–39. https://doi.org/10.1079/pns200194.

Kajimura S, Saito M. A new era in brown adipose tissue biology: molecular control of brown fat development and energy homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:225–49. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170252.

Sidossis L, Kajimura S. Brown and beige fat in humans: thermogenic adipocytes that control energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(2):478–86. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI78362.

Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Kayahara T, Kameya T, Kawai Y, et al. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3404–8. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI67803.

Hanssen MJ, Hoeks J, Brans B, van der Lans AA, Schaart G, van den Driessche JJ, et al. Short-term cold acclimation improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Med. 2015;21(8):863–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3891.

Iwen KA, Backhaus J, Cassens M, Waltl M, Hedesan OC, Merkel M, et al. Cold-Induced Brown Adipose Tissue Activity Alters Plasma Fatty Acids and Improves Glucose Metabolism in Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):4226–34. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2017-01250.

van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, Drossaerts JM, Kemerink GJ, Bouvy ND, et al. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1500–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0808718.

Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1526–31. https://doi.org/10.2337/db09-0530.

Matsushita M, Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Kameya T, Sugie H, Saito M. Impact of brown adipose tissue on body fatness and glucose metabolism in healthy humans. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(6):812–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.206.

Chondronikola M, Volpi E, Borsheim E, Porter C, Annamalai P, Enerback S, et al. Brown adipose tissue improves whole-body glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4089–99. https://doi.org/10.2337/db14-0746.

Nirengi S, Homma T, Inoue N, Sato H, Yoneshiro T, Matsushita M, et al. Assessment of human brown adipose tissue density during daily ingestion of thermogenic capsinoids using near-infrared time-resolved spectroscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2016;21(9):091305. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.21.9.091305.

Nirengi S, Amagasa S, Homma T, Yoneshiro T, Matsumiya S, Kurosawa Y, et al. Daily ingestion of catechin-rich beverage increases brown adipose tissue density and decreases extramyocellular lipids in healthy young women. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1363. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-3029-0.

Yoneshiro T, Matsushita M, Hibi M, Tone H, Takeshita M, Yasunaga K, et al. Tea catechin and caffeine activate brown adipose tissue and increase cold-induced thermogenic capacity in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(4):873–81. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.144972.

Fisher FM, Maratos-Flier E. Understanding the Physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol. 2016;78:223–41. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105339.

Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. A dozen years of discovery: insights into the physiology and pharmacology of FGF21. Cell Metab. 2019;29(2):246–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.01.004.

Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, Ford AM, Micanovic R, Galbreath EJ, et al. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(6):1627–35. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI23606.

Gaich G, Chien JY, Fu H, Glass LC, Deeg MA, Holland WL, et al. The effects of LY2405319, an FGF21 analog, in obese human subjects with type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2013;18(3):333–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.08.005.

Kaufman A, Abuqayyas L, Denney WS, Tillman EJ, Rolph T. AKR-001, an Fc-FGF21 analog, showed sustained pharmacodynamic effects on insulin sensitivity and lipid metabolism in type 2 diabetes patients. Cell Rep Med. 2020;1(4):100057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100057.

Hanssen MJ, Broeders E, Samms RJ, Vosselman MJ, van der Lans AA, Cheng CC, et al. Serum FGF21 levels are associated with brown adipose tissue activity in humans. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10275. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10275.

Taniguchi H, Shimizu K, Wada S, Nirengi S, Kataoka H, Higashi A. Effects of beta-conglycinin intake on circulating FGF21 levels and brown adipose tissue activity in Japanese young men: a single intake study and a randomized controlled trial. J Physiol Anthropol. 2020;39(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-020-00226-w.

Dushay JR, Toschi E, Mitten EK, Fisher FM, Herman MA, Maratos-Flier E. Fructose ingestion acutely stimulates circulating FGF21 levels in humans. Mol Metab. 2015;4(1):51–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2014.09.008.

Ter Horst KW, Gilijamse PW, Demirkiran A, van Wagensveld BA, Ackermans MT, Verheij J, et al. The FGF21 response to fructose predicts metabolic health and persists after bariatric surgery in obese humans. Mol Metab. 2017;6(11):1493–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2017.08.014.

Migdal A, Comte S, Rodgers M, Heineman B, Maratos-Flier E, Herman M, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 and fructose dynamics in humans. Obes Sci Pract. 2018;4(5):483–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/osp4.295.

Fisher FM, Kim M, Doridot L, Cunniff JC, Parker TS, Levine DM, et al. A critical role for ChREBP-mediated FGF21 secretion in hepatic fructose metabolism. Mol Metab. 2017;6(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2016.11.008.

Richard G, Blondin DP, Syed SA, Rossi L, Fontes ME, Fortin M, et al. High-fructose feeding suppresses cold-stimulated brown adipose tissue glucose uptake independently of changes in thermogenesis and the gut microbiome. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3(9):100742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100742.

Nirengi S, Wakabayashi H, Matsushita M, Domichi M, Suzuki S, Sukino S, et al. An optimal condition for the evaluation of human brown adipose tissue by infrared thermography. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220574. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220574.

Takahashi K, Yoshimura Y, Kaimoto T, Kunii D, Komatsu T, Yamamoto S. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire based on food groups for estimating individual nutrient intake. Jpn J Nutr Diet. 2001;59(5):221–32.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB.

Abu-Odeh M, Zhang Y, Reilly SM, Ebadat N, Keinan O, Valentine JM, et al. FGF21 promotes thermogenic gene expression as an autocrine factor in adipocytes. Cell Rep. 2021;35(13):109331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109331.

Kharitonenkov A, Wroblewski VJ, Koester A, Chen YF, Clutinger CK, Tigno XT, et al. The metabolic state of diabetic monkeys is regulated by fibroblast growth factor-21. Endocrinology. 2007;148(2):774–81. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2006-1168.

Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, Mirrahimi A, Yu ME, Carleton AJ, Beyene J, et al. Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(4):291–304. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00007.

Chiu S, Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, Cozma AI, Mirrahimi A, Carleton AJ, et al. Effect of fructose on markers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(4):416–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.8.

Taniguchi H, Tanisawa K, Sun X, Cao ZB, Oshima S, Ise R, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and visceral fat are key determinants of serum fibroblast growth factor 21 concentration in Japanese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):E1877–84. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1877.

Tyynismaa H, Raivio T, Hakkarainen A, Ortega-Alonso A, Lundbom N, Kaprio J, et al. Liver fat but not other adiposity measures influence circulating FGF21 levels in healthy young adult twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2):E351–5. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-1326.

Fisher FM, Chui PC, Antonellis PJ, Bina HA, Kharitonenkov A, Flier JS, et al. Obesity is a fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)-resistant state. Diabetes. 2010;59(11):2781–9. https://doi.org/10.2337/db10-0193.

Chen C, Cheung BM, Tso AW, Wang Y, Law LS, Ong KL, et al. High plasma level of fibroblast growth factor 21 is an independent predictor of type 2 diabetes: a 5.4-year population-based prospective study in Chinese subjects. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):2113–5. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-0294.

Bobbert T, Schwarz F, Fischer-Rosinsky A, Pfeiffer AF, Mohlig M, Mai K, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 predicts the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes in Caucasians. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1):145–9. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0703.

Ong KL, Januszewski AS, O’Connell R, Jenkins AJ, Xu A, Sullivan DR, et al. The relationship of fibroblast growth factor 21 with cardiovascular outcome events in the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes study. Diabetologia. 2015;58(3):464–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3458-7.

Shen Y, Zhang X, Xu Y, Xiong Q, Lu Z, Ma X, et al. Serum FGF21 is associated with future cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiology. 2018;139(4):212–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000486127.

Yu H, Xia F, Lam KS, Wang Y, Bao Y, Zhang J, et al. Circadian rhythm of circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 is related to diurnal changes in fatty acids in humans. Clin Chem. 2011;57(5):691–700. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2010.155184.

Chong MF, Fielding BA, Frayn KN. Mechanisms for the acute effect of fructose on postprandial lipemia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(6):1511–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/85.6.1511.

Denechaud PD, Dentin R, Girard J, Postic C. Role of ChREBP in hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(1):68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.084.

Camporez JP, Jornayvaz FR, Petersen MC, Pesta D, Guigni BA, Serr J, et al. Cellular mechanisms by which FGF21 improves insulin sensitivity in male mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154(9):3099–109. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2013-1191.

Vinales KL, Begaye B, Bogardus C, Walter M, Krakoff J, Piaggi P. FGF21 is a hormonal mediator of the human “thrifty” metabolic phenotype. Diabetes. 2019;68(2):318–23. https://doi.org/10.2337/db18-0696.

Taniguchi H, Tanisawa K, Sun X, Higuchi M. Acute endurance exercise lowers serum fibroblast growth factor 21 levels in Japanese men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;85(6):861–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.13162.

Taniguchi H, Tanisawa K, Sun X, Kubo T, Higuchi M. Endurance exercise reduces hepatic fat content and serum fibroblast growth factor 21 levels in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(1):191–8. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2015-3308.

Levy SB, Leonard WR. The evolutionary significance of human brown adipose tissue: Integrating the timescales of adaptation. Evol Anthropol. 2022;31(2):75–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21930.

Fisher FM, Kleiner S, Douris N, Fox EC, Mepani RJ, Verdeguer F, et al. FGF21 regulates PGC-1alpha and browning of white adipose tissues in adaptive thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 2012;26(3):271–81. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.177857.111.

Lee P, Brychta RJ, Linderman J, Smith S, Chen KY, Celi FS. Mild cold exposure modulates fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) diurnal rhythm in humans: relationship between FGF21 levels, lipolysis, and cold-induced thermogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):E98-102. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-3107.

Lee P, Linderman JD, Smith S, Brychta RJ, Wang J, Idelson C, et al. Irisin and FGF21 are cold-induced endocrine activators of brown fat function in humans. Cell Metab. 2014;19(2):302–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.017.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Fumika Sano, Shiori Yoshida, and Kazuo Nagano for their assistance in the BAT activity measurements.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 20K19680 and 23K10849.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK and HT designed this study. HK, SN, and HT interpreted the data. HK and YM collected and analyzed the data. HT was a major contributor to writing the manuscript, and SN substantively revised it. HT supervised the entire study. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent before enrolment in the present study, which was approved by the Ethical Committee of Kyoto Prefectural University (Approval number 216).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kataoka, H., Nirengi, S., Matsui, Y. et al. Fructose-induced FGF21 secretion does not activate brown adipose tissue in Japanese young men: randomized cross-over and randomized controlled trials. J Physiol Anthropol 43, 5 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-023-00353-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40101-023-00353-0