Abstract

Background

This study aims to measure the output torque and analyze the exhaust elements of a small diesel engine that use the diesel fuel mixed with waste cooking oil to validate the driving and environmental characteristics of this fuel.

Methods

The fuel used was diesel fuel mixed with 15% of waste cooking oil, a small quantity of additives and was produced with no complicated refining process (WCO15). Continuous driving experiments were conducted for 90 min with it and the results were compared with the data obtained with pure diesel fuel (WCO0).

Results

As for the engine driving characteristics, engine speed, output torque, and fuel consumption were measured. As for the exhaust, a statistical analysis was conducted on temperature, O2, CO2, NO, and NO2.

Conclusions

As a result, the torque of WCO15 was 65.6% in comparison with WCO0 at the engine speed of 3600 rpm. In either fuel, the O2 concentration and temperature of exhaust showed a negative correlation, while CO2 and NO concentration showed a positive correlation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

During the last century, mankind has continued to develop products of high energy efficiency and low consumption. As the issue of climate changes is a worldwide problem, however, people seek better energy efficiency, emphasizing the need to produce fuel that would not negatively affect our natural environments (Venkanna and Venkataramana Reddy 2012; Subramanian and Lahane 2013). There are existing studies that evaluated vegetable oil or waste cooking oil as a new energy source for fuel and various measures were taken accordingly. However, a number of alternative fuels in use of new vegetable oil involve problems such as high freezing point, low efficiency to costs due to the small-scale farming area for small country (Hill et al. 2006; de Gorter and Just 2010; Mythili et al. 2014). Moreover, the vegetable oil, extracted from the farm products using the same cultivated lands and growing methods as food for human or feed for animals, has caused various economical problems (Runge and Senauer 2007). Especially in view of developing countries where food shortage is a major issue exist, utilizing agricultural products as a fuel resource causes another humanitarian problems. Furthermore, as the research on making vegetable oil progresses, the prices of related agricultural products increase and the effects to the cost decrease. Hence, it is expected to take a longer period of time from the step of research to the point of commercialization (Mitchell 2008).

Accordingly, many researches are actively conducted on the use of waste cooking oil, which was already used once in cooking, for the resource in manufacturing soap, fuel, etc. Since waste cooking oil contains a high level of calorific value, it can be utilized as an alternative energy resource for fossil fuel, which also would contribute to reducing the workload for disposal of waste cooking oil (McHenry 2012). In particular, it is reported that the existing disposal process of waste cooking oil causes serious negative effects on water quality (Hunter et al. 1997). As of 2009, vegetable oil is produced as much as 144,162 kt around the world and consumed as much as 11.5 kg per person in a year. When it is converted to the calorific value, 1159 J (277 kcal) is consumed a day (FAO 2009). In Korea, for instance, the consumption of vegetable oil is around 1000 kt that the amount of waste cooking oil is about 200 kt, only 40% (80–100 kt) of which is collected and recycled. The rest of the waste cooking oil is treated as general waste. When 20 ml of waste cooking oil is disposed through the sewage without proper treatment, it generates 5 ppm of BOD. In this case, about 4000 l of water per 20 ml is required to dilute it. Especially in many Asian countries where the use of vegetable oil is common, it is of great urgency to seek a way to treat vegetable oil. Since the amount of calorific value of waste cooking oil is 33.3–35.7 MJ/1 l, how to utilize it is also an important challenge (Gelfand et al. 2010).

According to Utlu and Koçak (2008), in an engine driving experiment in use of waste cooking oil with the revolution rate constant, the engine torque and NOx were almost the same, CO decreased as much as 17%, fuel consumption and CO2 increased as much as 14 and 8% respectively in comparison with diesel fuel.

According to Ghobadian et al. (2009), an engine driving experiment was conducted in use of biodiesel whose 0–50% is waste cooking oil in addition to pure diesel fuel. Based on the resulting data, a method to evaluate the characteristics was developed by means of an artificial neural network. As a result, it turned out that in terms of engine output and torque, waste cooking oil and diesel fuel had no significant difference.

This study aims to measure the output torque and analyze the exhaust elements of a small diesel engine that use the diesel fuel mixed with waste cooking oil to validate the operational and environmental characteristics of this fuel. The fuel used was diesel fuel mixed with 15% of waste cooking oil, a small quantity of additives (WCO15) and was produced with no complicated refining process. We used waste rapeseed oil as the waste cooking oil for the blend oil with conventional diesel fuel. The manufacturing process of this mixed fuel is simple compared to biodiesel that requires esterification, and thus it is possible to mix the additional element with the existing fuel at the site where it would be used. Only by adding a small quantity of additives, waste cooking oil had not been separated from diesel oil.

Methods

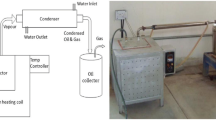

Experimental set-up

As shown in Fig. 1, the engine driving device used in the experiment consists of the diesel engine, the dynamometer, and exhaust measuring unit. The experimental engine is L40ASS of Yanmar Co. and the dynamometer is MB302/5-BD of Toyodenki Co. respectively. The major specifications are presented in Tables 1, 2.

Materials

Fuels to be compared are WCO0 and WCO15, whose major specifications are presented in Table 3. Additive composed mainly with oleic acid was blended to prevent the separation of cooking oil from diesel fuel. The property of the blended fuel was measured as shown in Table 4.

Experimental procedure

The temperature and relative humidity of the experiment environment were 28° and 70% respectively. The engine was warmed up for 30 min before the 90 min driving experiment through which the engine driving characteristics and exhaust elements were measured. Data sampling was conducted at every minute. Since the experimental engine had a speed governor, the speed setting was adjusted to the full so that the rated revolution per minute of the crank shaft could be maintained to the level of 3600 rpm, with the load of the dynamometer manually controlled. The engine speed was measured by means of the revolution indicator TDP-3321A-E (Coco Research Co.). The torque at the cam shaft of the engine was measured by means of the dynamometer. For the measurement of exhaust temperature, O2, CO2, NO, NO2 and NOx, HT-2300 (HODAKA Co.) was utilized.

Statistical analysis of measured data

Each fuel combustion experiment lasted for 90 min, during which the engine rpm changed a bit. Since the change was insignificant, however, it was assumed that the regular distribution of the engine speed was constant for each fuel over 3600 rpm. Thereafter, T-test was conducted to verify the significance of difference in arithmetic means values of the driving and exhaust characteristics of the measured variables. As for other measurements, to overview general tendency as well as the descriptive statistics for each fuel type, a hypothesis for a further statistical analysis, based on the bivariate correlation, was established.

In addition, Eq. (1) was used to calculate the brake power (kW) with the torque (Nm) from the dynamometer.

The statistical analysis was conducted by means of IBM SPSS V22 (2013).

Results

To comparatively evaluate variables, the values of Pearson correlation coefficient were calculated in a way of the bivariate correlation analysis of the two fuels’ measurements, which are presented in Table 5.

As for the O2 concentration in the exhaust of each fuel, it is in a negative correlation to CO2, NOx, torque, and brake power, which indicates that the correlation between the break power of a diesel engine and O2 concentration is high. The CO2 concentration in exhaust was in a positive correlation to NOx, brake power, and torque. This is because the consumption of O2 generated CO2 and NOx and the energy conversion resulted in the corresponding brake power and torque. In addition, the NOx concentration in exhaust was a sum of substances such as NO and NO2, and thus it was in a “positive” correlation to the CO2 concentration. In this experiment, no correlation was found between the control variable engine speed (rpm) and other variables.

Based on the descriptive statistics above, the hypotheses from [A] to [C] below were set for the further statistical interpretation, the correlation between parameters was analyzed, and the simple linear regression analysis were made as follows:

-

A.

There is difference in driving torque between engines that use fuel WCO0 and WCO15.

-

B.

There are differences in exhaust elements between engines that use fuel WCO0 and WCO15.

-

C.

In each engine that uses fuel WCO0 and WCO15, there are correlations between exhaust elements and each torque.

To sum up, these are hypotheses that are to investigate which kind of difference there are in torque and exhaust elements using WCO0 and WCO15 as fuel. As for the rpm of engine used in the experiment, 3600 rpm was set as the control variable, and the arithmetic mean values and standard deviations were 3603.9 ± 2.9 (WCO0) and 3603.6 ± 1.6 (WCO15) respectively. In T-test, the null hypothesis that ‘There is difference between WCO0 and WCO15 in engine rpm data’ was not within the range of significant difference of 5% (p = 0.321), and thus no difference in engine rpm between data sets was assumed in further data analyses.

The box plot of measurements of each fuel is presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9.

The arithmetic mean value and standard deviation of exhaust temperature of each fuel were 126.9 ± 1.9 °C (WCO0) and 140.5 ± 1.6 °C (WCO15) respectively. In comparison with WCO0, the exhaust temperature of WCO15 increased as much as 10.7%. In T-test of this result, the null hypothesis that ‘There is no difference in exhaust temperature between WCO0 and WCO15’ was denied (p = 0.000).

The arithmetic mean values and standard deviations of O2 (%) concentration in exhaust were 18.0 ± 0.0 (WCO0) and 18.7 ± 0.0 (WCO15) respectively, which indicates that in comparison with WCO0, that of WCO15 increased as much as 3.9% (p = 0.000).

The arithmetic mean values and standard deviations of CO2 (%) concentration were 2.1 ± 0.0 (WCO0) and 1.7 ± 0.0 (WCO15) respectively, which indicates that in comparison with WCO0, that of WCO15 decreased as much as 19.1% (p = 0.000).

The arithmetic mean values and standard deviations of NO concentration (ppm) were 47.5 ± 1.9 (WCO0) and 36.2 ± 3.5 (WCO15) respectively, which indicates that in comparison with WCO0, that of WCO15 decreased as much as 23.8% (p = 0.000).

The arithmetic mean values and standard deviations of NO2 concentration (ppm) were 16.9 ± 1.0 (WCO0) and 5.7 ± 0.6 (WCO15) respectively, which indicates that in comparison with WCO0, that of WCO15 decreased as much as 66.3% (p = 0.000).

The arithmetic mean values and standard deviations of NOx concentration (ppm) were 64.4 ± 2.0 (WCO0) and 41.9 ± 3.6 (WCO15) respectively, which indicates that in comparison with WCO0, that of WCO15 decreased as much as 34.9% (p = 0.000).

The arithmetic mean values and standard deviations of the engine torque (Nm) were 48.5 ± 0.9 (WCO0) and 31.8 ± 2.7 (WCO15) respectively, which indicates that in comparison with WCO0, that of WCO15 decreased as much as 65.6% (p = 0.000).

The arithmetic mean values and standard deviations of the engine brake power (kW) in the combustion experiment were 0.93 ± 0.02 (WCO0) and 0.61 ± 0.05 (WCO15) respectively, which indicates that in comparison with WCO0, that of WCO15 decreased as much as 65.6% (p = 0.000).

The correlations between torque and each of other variables were examined in the distribution diagram of WCO0 and WCO15, and the results are presented in Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15 (Bluman 2013).

Discussion

Figure 3 shows that since WCO0 has a higher engine output than WCO15 and the O2 concentration in exhaust elements is lower, the combustion of WCO0 is close to complete combustion (Wei et al. 2003; Forson et al. 2004; Agrawal et al. 2004; Virtanen et al. 2004; Li et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2006). In general, with the engine speed maintained constantly in the experiment, the torque was in a “positive” correlation with NO and NOx, which is in correspondent to the existing studies. As for the correlations between the torque and NO and NOx, this study verifies that those of WCO0 were stronger than those of WCO15. Additionally, NOx emission from a vehicle engine is viewed as an exhaust element that is decided by the Air Fuel Ratio of the engine (Isomura and Norimatsu 1981; Nakagawa et al. 1991; Ben et al. 1999). The NOx concentration in exhaust of a diesel engine tends to increase as it is closer to complete combustion (Fig. 7). When the combustion of an engine approaches a complete combustion, the concentration of the NOx generally tends to become high, so vehicle engines sometimes avoid the complete combustion intentionally to reduce NOx emission. In our experiments, there is a possibility that complete combustion was suppressed by including waste cooking oil to diesel fuel and as a result the emission of NOx was reduced. Primarily, waste cooking oil is to be abandoned under appropriate treatment. This process may evoke large burden to the environment in case the treatment is not adequate. When such waste cooking oil is employed as the ingredient of mixed fuel, it may be able to reduce the environmental burden.

Based on the experiment results above, it is thought that the waste cooking oil mixed fuel used in the study can be used in the same manner with existing diesel fuel although the brake power is inferior as shown in Fig. 8. Exhaust characteristics, etc. are almost the same with other fuels used in common diesel engines.

As for the major characteristics of WCO15 used in the experiment, when the ratio of waste cooking oil in the mixed fuel was 15%, there was no need to renovate the engine (He et al. 2008). It is also advantageous in that the initial expense is relatively low if recyclable elements are more reasonable than diesel oil used in the fuel. Hence, it is expected that this type of fuel can contribute to meeting demands for eco-friendly and low-cost fuel in diesel engines that do not require a high level of output. As for the gain and loss, the comprehensive policies need to be discussed with regard to the disposal cost of waste cooking oil as well. Especially regarding specific environmental suitability, such considerations as Life Cycle Assessment and Risk Assessment need to be implemented with the results fully reflected (Gravalos et al. 2009).

Conclusions

The driving characteristics and the exhaust elements of a small diesel engine that uses the diesel fuel mixed with waste cooking oil were measured. The fuel used was diesel fuel mixed with 15% of waste cooking oil, a small quantity of additives and was produced with no complicated refining process. Continuous driving experiments were conducted for 90 min with it. The results were compared with the data obtained with pure diesel fuel.

In the experiment with the engine speed controlled constantly, it turned out that the torque was in positive correlations with NO and NOx. As for correlations between the torque and NO and NOx, it turned out that those of WCO0 were stronger than those of WCO15. The engine brake power of WCO0 was higher than that of WCO15, and the O2 concentration in exhaust elements was lower, which indicates that the combustion of WCO0 was closer to complete combustion. In general, with the engine speed maintained constantly in the experiment, the torque was in a “positive” correlation with NO and NOx, which is in correspondent to the existing studies. As for the correlations between the torque and NO and NOx, this study verifies that those of WCO0 were stronger than those of WCO15. The NOx concentration in exhaust of a diesel engine tends to increase as it is closer to complete combustion.

As the result, the torque of WCO15 was 65.6% in comparison with WCO0 at the engine speed of 3600 rpm. In either fuel, the O2 concentration and temperature of exhaust showed a negative correlation while CO2 and NO concentration showed a positive correlation.

Based on the experiment results above, it is thought that the waste cooking oil mixed fuel used in the study can be used in the same manner with existing diesel fuel although the brake power is inferior as shown in Fig. 8. Exhaust characteristics, etc. are almost the same with other fuels used in common diesel engines.

In conclusion, as for the characteristics of diesel fuel mixed with waste cooking oil, when the mixing ratio of waste cooking oil was about 15%, there was no need to renovate the engine. It is thought, therefore, that this type of fuel can contribute to meeting demands for eco-friendly and low-cost fuel in diesel engines that do not require a high level of output. As for gain and loss, the comprehensive policies need to be discussed with regard to the disposal cost of waste cooking oil as well.

Abbreviations

- WCO0:

-

light oil (non-waste cooking oil)

- WCO15:

-

waste cooking oil (waste cooking oil 15% + light oil 84% + additives 1%)

- O2:

-

oxygen

- CO2:

-

carbon dioxide

- NO:

-

nitric oxide

- NO2:

-

nitrogen dioxide

- NOx:

-

nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide

- rpm:

-

revolution per minute

References

Agrawal AK, Singh SK, Sinha S, Shukla MK (2004) Effect of EGR on the exhaust gas temperature and exhaust opacity in compression ignition engines. Sadhana. 29(3):275–284

Ben L, Raud-Ducros N, Truquet R, Charnay G (1999) Influence of air/fuel ratio on cyclic variation and exhaust emission in natural gas SI engine. SAE Techn Paper. https://doi.org/10.4271/1999-01-2901

Bluman AG (2013) Elementary statistics. McGraw Hill, Chennai

de Gorter H, Just DR (2010) The social costs and benefits of biofuels: the intersection of environmental, energy and agricultural policy. Appl Eco Perspect Policy 32(1):4–32

FAO (2009) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT

Forson F, Oduro E, Hammond-Donkoh E (2004) Performance of Jatropha oil blends in a diesel engine. Renew Energy 29(7):1135–1145

Gelfand I, Snapp SS, Robertson GP (2010) Energy efficiency of conventional, organic, and alternative cropping systems for food and fuel at a site in the US Midwest. Environ Sci Technol 44(10):4006–4011

Ghobadian B, Rahimi H, Nikbakht AM, Najafi G, Yusaf TF (2009) Diesel engine performance and exhaust emission analysis using waste cooking biodiesel fuel with an artificial neural network. Renew Energy 34(4):976–982

Gravalos I, Gialamas T, Koutsofitis Z, Kateris D, Xyradakis P, Tsiropoulos Z, Lianos G (2009) Comparison of performance characteristics of agricultural tractor diesel engine operating on home and industrially produced biodiesel. Int J Energy Res 33(12):1048–1058

He C, Ge Y, Tan J, Han X (2008) Spray properties of alternative fuels: a comparative analysis of biodiesel and diesel. Int J Energy Res 32(14):1329–1338

Hill J, Nelson E, Tilman D, Polasky S, Tiffany D (2006) Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103(30):11206–11210

Hunter W, Follett R, Cary J (1997) Use of vegetable oil to remove nitrate from flowing groundwater. Trans ASAE 40(2):345–353

IBM (2013) IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0

Isomura S, Norimatsu H (1981) Air-fuel ratio control system. US 4,251,989

Li DG, Zhen H, Xingcai L, Wu-gao Z, Jian-Guang Y (2005) Physico-chemical properties of ethanol-diesel blend fuel and its effect on performance and emissions of diesel engines. Renew Energy 30(6):967–976

McHenry MP (2012) Small-scale (≤ 6 kW) stand-alone and grid-connected photovoltaic, wind, hydroelectric, biodiesel, and wood gasification system’s simulated technical, economic, and mitigation analyses for rural regions in Western Australia. Renew Energy 38(1):195–205

Mitchell D (2008) A note on rising food prices. World Bank, Washington DC

Mythili R, Venkatachalam P, Subramanian P, Uma D (2014) Production characterization and efficiency of biodiesel: a review. Int J Energy Res 38:1233–1259

Nakagawa T, Saito M, Sanbuichi H, Terasaka K (1991) Air/fuel ratio feedback control system for lean combustion engine. United States patent US 4,729,220

Runge CF, Senauer B (2007) How biofuels could starve the poor. Foreign affairs, New York, pp 41–53

Subramanian KA, Lahane S (2013) Comparative evaluations of injection and spray characteristics of a diesel engine using karanja biodiesel-diesel blends. Int J Energy Res 37(6):582–597

Utlu Z, Koçak MS (2008) The effect of biodiesel fuel obtained from waste frying oil on direct injection diesel engine performance and exhaust emissions. Renew Energy 33(8):1936–1941

Venkanna BK, Venkataramana Reddy C (2012) Direct injection diesel engine performance, emission, and combustion characteristics using diesel fuel, nonedible honne oil methyl ester, and blends with diesel fuel. Int J Energy Res 36(13):1247–1261

Virtanen AK, Ristimäki JM, Vaaraslahti KM, Keskinen J (2004) Effect of engine load on diesel soot particles. Environ Sci Technol 38(9):2551–2556

Wang YD, Al-Shemmeri T, Eames P, McMullan J, Hewitt N, Huang Y, Rezvani S (2006) An experimental investigation of the performance and gaseous exhaust emissions of a diesel engine using blends of a vegetable oil. Appl Thermal Eng 26(14):1684–1691

Wei X, Del Re L, Langthaler P (2003) LPV dynamical models of diesel engine nox emission. Modeling and control of economic systems 2001: (SME 2001). In: A proceedings volume from the 10th IFAC symposium, Klagenfurt, Austria, 6–8 September 2001. p 245

Authors’ contributions

MSC: research director and research manager. TF: exhaust gas measurement. HTK: english composition and statistical analysis. XLW: analysis of exhaust gas. KS: design of research and overall review of research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The research was funded by The Japan Science Society (26-624). A special thanks to the field assistant for invaluable help with data collection and processing in Mie University Environmental Information and Technology Laboratory.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, M.S., Fukushima, T., Kim, H.T. et al. Engine drive and environmental characteristics when fuel mixed with waste cooking oil is used for a small diesel engine. Environ Syst Res 7, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-017-0104-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-017-0104-7