Abstract

Introduction

Reconstruction after wide resection for a sarcoma involving the knee extensor mechanism is challenging even if the tumor is small.

Case description

We report on four consecutive peri-patellar tendon sarcomas treated similarly at a single institution. Histological diagnoses were synovial sarcoma (two cases), clear cell sarcoma and extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma (one case each). Follow-up periods after surgery were 18–67 months. All cases underwent pre-operative radiotherapy and subsequent surgery. After preoperative radiotherapy and wide resection including the patellar tendon, bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft was fixed to the residual patella and tibial tuberosity with screws and a cable wire. Soft tissue and skin defect over allograft was covered by free antero-lateral thigh flap. Post-operatively, the operated knee was splinted straight for at least 6 weeks, and then range-of-motion exercise was gradually introduced. Except for one case with a proximal tibial stress fracture 5 months post-operatively, no complication was observed. Both bone–bone junctions between allograft and residual bones were united within 1 year after surgery. At the latest clinical follow-up, all the patients had satisfactory functions with Musculoskeletal Tumor Society score of 28–30 out of 30 points and virtually full range of motion.

Discussion and evaluation

This case series is the first to report bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft for reconstruction after tumor resection with joint preservation and with satisfactory clinical outcomes.

Conclusions

Bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft reconstruction with vascularized flap reconstruction is a viable option for peri-patella tendon sarcomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The mainstay of soft tissue sarcoma treatment for cure is surgical resection with or without adjuvant therapy, but functional loss after wide resection sometimes can be crucial. If a sarcoma involves or abuts on the knee extension mechanism, functional reconstruction after resection can be complex and challenging as in patellar tendon ruptures after total knee replacement (TKR). Several single case reports of peri-patellar tendon sarcomas reconstructed by a recycled bone (Muramatsu et al. 2010), bone-tendon grafts (Peyser and Makley 1996; Osanai et al. 2008; Nakashima et al. 2012), a muscle flap (Machens et al. 2005) and a tendon graft (Fukui et al. 1999), have been reported, mainly from Japan where the use of allograft is fairly limited.

Allograft is a well-established reconstruction option for musculoskeletal defect, including reconstruction for bone sarcomas and disruption of the extensor mechanism related to TKR (Rosenberg 2012; Hornicek et al. 1998). Although allograft can be associated with a high rate of infection and fracture if used massively for bony reconstruction, it has several advantages including simple procedure, less invasiveness to patients with no necessity of harvesting tendon, and the preservation of the whole specimen for accurate histological analysis when used for musculoskeletal tumors. In our surgical team, the combination of patellar tendon allograft with bony attachment on both ends and vascularized flap coverage has been used since 2009 because this reconstruction was expected to offer satisfactory limb functions with oncological safety, less procedural complexity, and minimal complications.

The aim of this study is to highlight a novel reconstruction option using bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) allograft for peri-patellar tendon sarcomas, including post-operative management, and to reveal its advantages and disadvantages compared to previous reports.

Case description

This is a case series of 4 consecutive peri-patella-tendon sarcomas surgically treated with the same allograft and flap reconstruction at our institution between 2009 and 2014. Prior to this study, the institutional review board approval was obtained (HREC-A: QA 117/14). Patients were all male aged 26–72 years at the time of surgery, with follow-up periods of 18–67 (mean 40.8) months. Histological diagnoses were synovial sarcoma (two cases), clear cell sarcoma and extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma (one case each). Three out of the four cases had undergone unplanned excision externally with inadequate margin before referral. All the cases underwent pre-operative radiotherapy comprised of external beam 50.4 Gy in divided doses over 28 sessions, and one extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma case received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. All cases achieved wide margin according to the Enneking classification (Enneking et al. 1980), with microscopically negative margin. Patient background and clinical results are summarized in Table 1. Post-operatively, the patients were managed similarly but modified from the preceding case(s) in terms of the period of keeping the operated knee straight in splint (Table 2). Clinical review of each case followed our follow-up protocol: every 3 months for the first 2 years for intermediate- or high-grade soft tissue sarcomas after surgery, with physical examination, chest computed tomography for lung metastasis surveillance and X-ray to evaluate bone union at junctions between the implanted allograft and host bones. Because of the screws and cable wire, magnetic resonance imaging study was not routinely performed for local recurrence surveillance in this case series.

Patient 1

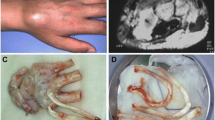

A 25-year-old man was referred after excision of a painful 2-cm nodule in the left infrapatellar region. Pathological diagnosis was synovial sarcoma (Fig. 1a). Because of positive margin, pre-operative radiotherapy and subsequent re-excision were performed. The whole patellar tendon, infrapatellar fat pad, inferior one-third of the patella, and the tibial tuberosity were removed together with 6 × 12 cm of the skin including previous operation scar. Using an oblique osteotomy, nearly the whole original patellar-femoral joint surface of the patella was preserved. Following resection, BPTB allograft was harvested and shaved to fit the osteotomy sites. Then, the allograft was fixed to the residual patella and proximal tibia with screws and a stainless steel Dall-Miles 2-mm Cable and Sleeve Set (Stryker Australia Pty., Ltd.) tightened at 30° knee flexion (Fig. 1b). The soft tissue defect was covered with a free ipsilateral antero-lateral thigh (ALT) flap.

Radiologic studies and photographs of patient 1. a T1 gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance images at the first presentation show inflammation in the infrapatellar fat pad after unplanned excision. b Photographs show intra-operative field before and after allograft reconstruction. White arrows and black arrows point screws and a cable wire system, respectively. c Both bone–bone junctions between allograft and residual bones were united at 11 months after surgery. T tibia, F femoral joint surface, P patella

Post-operative course was uneventful without wound complication or infection. The operated knee was kept straight in splint for the first 3 months, and then gentle passive and active range-of-motion (ROM) exercise was started. Full weight bearing (FWB) was tolerated immediately after surgery but only in the setting of using crutches for the first 6 weeks. Three months after surgery, progressive ROM exercise and FWB without splint were allowed. Both bone–bone junctions were united 11 months post-operatively (Fig. 1c). After both bone–bone junctions were united, sports activity, including fun skiing, was permitted. At 67 months after surgery, the patient was continuously free of disease. His left knee function was virtually normal, with no extension lag and knee flexion of 130° (Fig. 2; Additional file 1: Movie S1). Quadriceps manual muscle test was 5/5. Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score was 30/30 (Enneking et al. 1993).

Patient 2

A 56-year-old man was referred after unplanned excision of an infrapatellar 35-mm nodule. The pathological diagnosis was clear cell sarcoma. After pre-operative radiotherapy, the same area as in patient 1 was removed because of similar tumor location, BPTB allograft was fashioned to fit the defect, and the allograft was covered by the free contralateral ALT flap. Post-operative course was uneventful. Post-operative management was similar to Patient 1, with the reduced period of the knee brace maintained in straight of 8 weeks, reflecting on the slightly limited ROM in the previous case. Bone union was completed 1 year after surgery. At 48 months post-operatively, the patient was continuously free of disease and his knee function was satisfactory, with minor knee extension lag (<5°), knee flexion of 145°, full muscle strength and MSTS score of 30/30.

Patient 3

A 28-year-old man was referred after unplanned excision of an infrapatellar 4-cm nodule. The pathologic diagnosis was extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma. After neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, re-excision and reconstruction with BPTB allograft and ALT flap were performed, similar to patients 1 and 2. Post-operative management was similar to the previous 2 cases, with the reduced period of the knee brace maintained in straight of 6 weeks. Post-operative course was uneventful. Bone union was completed 1 year after surgery. At 30 months after surgery, the patient was continuously free of disease. The bone–bone junctions were united, and his knee function was satisfactory, with minor knee extension lag (<5°), knee flexion of 135°, full muscle strength and MSTS score of 30/30.

Patient 4

A 72-year-old man presented with a 9-cm painless mass in the right knee just lateral to the distal end of patellar tendon. The tumor was located subcutaneously and intra-muscularly but partially invaded into the lateral cortex of the proximal tibia (Fig. 3a). Core needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of synovial cell sarcoma. After pre-operative radiotherapy, wide resection included the lower one-third of the patella, the whole patellar tendon, infrapatellar fat pad, anterior lateral knee joint capsule, and one anterior-lateral third in axial section of the proximal tibia extending more distal than the previous cases. After resection, BPTB allograft was fixed to the residual patella and proximal tibia with screws. A lateral proximal tibial plate and screws were added but no cable wire was added because the suitable hole site for cable wiring, just distal to the tibial tuberosity, was resected (Fig. 3b). Post-operatively, we managed this patient similar to the previous patients, maintaining the operated knee straight in splint for the first 8 weeks. Five months post-operatively, an increasingly painful stress fracture of the proximal tibia was diagnosed (Fig. 3c). The fracture was fixed with another plate. Bone union between the implanted allograft and host bones was completed 1 year after surgery. At 18 months after the initial surgery, the fracture site was united, FWB was tolerated, but the knee ROM was restricted with −10° of extension and 115° of flexion. MSTS score was 28/30 (93 %).

Radiologic studies and photographs of patient 4. a T1 gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance images of at the first presentation demonstrate partial tumor invasion into the lateral cortex of the proximal tibia (arrow). b After allograft reconstruction, the proximal tibia was reinforced with a lateral proximal tibial plate and screws. c Radiographs show a stress fracture in the proximal tibia 5 months post-operatively. A black arrow and white arrow point a thin oblique fracture line and posterior fracture-associated callus formation, respectively

Discussion and evaluation

With advances in surgical techniques, imaging technology, and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, approximately 90 % of extremity sarcomas can be treated with limb-salvage surgeries, without sacrificing oncological results (Henshaw and Malawer 2001). However, reconstruction after wide resection for sarcomas involving the patellar tendon can be challenging, with difficulty in obtaining satisfactory function even if the tumor is small. Because of its rarity, only a limited number of single cases using autologous or recycled graft for reconstruction have been published (Table 3) (Muramatsu et al. 2010; Peyser and Makley 1996; Osanai et al. 2008; Nakashima et al. 2012; Machens et al. 2005; Fukui et al. 1999), but to our knowledge the use of BPTB allograft for sarcoma cases has not been reported.

Patellar tendon ruptures associated with TKR, a similar clinical situation requiring re-establishment of knee extension mechanism, are more common and have been well studied. Common reconstruction options include direct suture of tendon tear for acute cases, autologous tendon graft using the hamstrings or gracilis tendon(s), Achilles tendon allograft with calcaneus bone block, and BPTB allograft for re-rupture or chronic cases (Cadambi and Engh 1992; Crossett et al. 2002; Malhotra et al. 2008; Brooks 2009). In the case series of BPTB allograft reconstruction by Malhotra R et al. (Malhotra et al. 2008), both junctions of allograft and host tissue were bone–bone instead of soft tissue-soft tissue, similar to our method, and their results were satisfactory at 14–30 months after patellar tendon reconstruction.

The four cases included in this case series had virtually full knee function without major complications, except for one fracture. The key points of our method include (1) bone–bone junctions between allograft and host tissue, (2) (if possible) reinforcement with a circlage cable wire through the proximal tibia intra-osseously and the quadriceps just above the superior patellar pole, (3) free flap coverage, (4) oblique osteotomy of the inferior patella, and (5) case-by-case post-operative management.

The rationale for our approach is as follows. Firstly, bone–bone junction appears superior to soft tissue-soft tissue junction, especially for allograft reconstruction. Indeed, poor long-term functions of quadriceps-patella-patellar tendon-bone allograft were reported (Emerson et al. 1994; Nazarian and Booth 1999). This late failure was thought due to loosening or healing process problems in the proximal quadriceps–quadriceps junction. Secondly, the lack of vascularity of allograft tissue and hypovascularity of irradiated tissue are major concerns for our method, and the durability of BPTB in the setting of reconstruction after radiation is uncertain. In our case series, allograft was covered with a non-irradiated vascularized flap. We speculate that the use of free flap could improve the re-vascularization and internal repair of allograft, although there may still remain a consistent risk of failure. Further follow-up and attention is necessary for possible patellar tendon rupture on a long-term bases. Thirdly, for the first 1–2 years before incorporation and healing of host allograft tissue (Roberts et al. 1991; Muramatsu et al. 2008), circlage cable wire support is thought to be useful to protect the integrity of patellar tendon allograft. A similar use of cable loop for repair protection was reported by Brooks (Brooks 2009). To minimize functional loss and avoid bulky appearance, we chose antero-lateral thigh flap. Fourthly, the degenerative change caused by allograft replacement is predicted to be minimal because the oblique osteotomy of the inferior patella in our method can preserve nearly the whole original cartilage surface of the patella (Fig. 4). Lastly, bone deficit can vary depending on tumor location and may need longer weight-bearing restriction to avoid post-operative fracture as in one patient in our case series. Rosenberg reported 3 cases (6 %) of post-operative fracture at the site of the tibial bone block after allograft reconstruction for TKR-related patellar tendon ruptures (Rosenberg 2012). The risk of post-operative tibial fracture cannot be ignored especially where preoperative radiotherapy is also used which is known to weaken bone.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we reported a new reconstruction option for patellar tendon deficit after sarcoma resection using BPTB allograft and free flap reconstruction. This novel method can be a viable reconstruction option promising satisfactory clinical outcomes for peri-patellar tendon sarcomas. Long-term restriction of activity including weight-bearing should be considered to prevent post-operative fracture if a larger proportion of proximal tibia is involved in wide resection.

Consent

Informed consent for publication of individual patient data, including photographs, images and video, was obtained from the patients.

Abbreviations

- BPTB:

-

bone-patellar tendon-bone

- TKR:

-

total knee replacement

- ROM:

-

range of motion

- FWB:

-

full weight bearing

- MSTS:

-

musculoskeletal tumor society

- ALT:

-

antero-lateral thigh

References

Brooks P (2009) Extensor mechanism ruptures. Orthopedics. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090728-31

Cadambi A, Engh GA (1992) Use of a semitendinosus tendon autogenous graft for rupture of the patellar ligament after total knee arthroplasty. A report of seven cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 74(7):974–979

Crossett LS, Sinha RK, Sechriest VF, Rubash HE (2002) Reconstruction of a ruptured patellar tendon with achilles tendon allograft following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84-A(8):1354–1361

Emerson RH Jr, Head WC, Malinin TI (1994) Extensor mechanism reconstruction with an allograft after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 303:79–85

Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA (1980) A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 153:106–120

Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ (1993) A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 286:241–246

Fukui N, Cho N, Tashiro T, Nakamura K (1999) Anatomical reconstruction of the patellar tendon: a new technique with hamstring tendons and iliotibial tract. J Orthop Trauma 13(5):375–379

Henshaw R, Malawer MM (2001) Review of endoprosthetic reconstruction in limb-sparing surgery. In: Malawer MM, Sugarbaker PH (eds) Musculoskeletal cancer surgery. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 384–404

Hornicek FJ Jr, Mnaymneh W, Lackman RD, Exner GU, Malinin TI (1998) Limb salvage with osteoarticular allografts after resection of proximal tibia bone tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 352:179–186

Machens HG, Siemers F, Kaun M, Krapohl B, Reichert B, Russlies M, Kruger S, Stockelhuber B, Mailander P (2005) Patellar tendon reconstruction using a free latissimus dorsi flap following resection of a prepatellar myxofibrosarcoma: case report. J Reconstr Microsurg 21(4):235–238. doi:10.1055/s-2005-871749

Malhotra R, Garg B, Logani V, Bhan S (2008) Management of extensor mechanism deficit as a consequence of patellar tendon loss in total knee arthroplasty: a new surgical technique. J Arthroplasty 23(8):1146–1151. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2007.08.011

Muramatsu K, Hachiya Y, Izawa H (2008) Serial evaluation of human anterior cruciate ligament grafts by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: comparison of allografts and autografts. Arthroscopy 24(9):1038–1044. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2008.05.014

Muramatsu K, Yoshida K, Fujii K, Okazaki T, Moriya A, Taguchi T (2010) Anatomical reconstruction of the knee extensor apparatus for prepatellar myxofibrosarcoma. Orthopedics 33(10):773. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100826-32

Nakashima H, Yoshida M, Miyamoto K (2012) Anatomical reconstruction of the patellar tendon using the fascia lata attached to the iliac bone following resection for soft tissue sarcoma: a case report. Ups J Med Sci 117(4):460–464. doi:10.3109/03009734.2012.689379

Nazarian DG, Booth RE Jr (1999) Extensor mechanism allografts in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 367:123–129

Osanai T, Tsuchiya T, Ogino T (2008) Gastrocnemius muscle flap including Achilles tendon after extensive patellectomy for soft tissue sarcoma. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 42(3):161–163. doi:10.1080/02844310601012015

Peyser AB, Makley JT (1996) Patellar tendon reconstruction augmented by a free autograft of the biceps tendon attached to the fibular head. Orthopedics 19(6):545–549

Roberts TS, Drez D Jr, McCarthy W, Paine R (1991) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using freeze-dried, ethylene oxide-sterilized, bone-patellar tendon-bone allografts. Two year results in thirty-six patients. Am J Sports Med 19(1):35–41

Rosenberg AG (2012) Management of extensor mechanism rupture after TKA. J Bone Joint Surg Br 94(11 Suppl A):116–119. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B11.30823

Authors’ contributions

PC invented this reconstruction method, and PC and DG operated on all the patients. JI conducted literature review and drafted the whole manuscript. PC and DG edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Deborah May, Clinical Research Nurse of Department of Orthopaedics at St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne for her assistance in data collection.

This study was conducted at St. Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne, in accordance with the ethical standards in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained prior to this study. Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Imanishi, J., Grinsell, D. & Choong, P.F.M. Bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft reconstruction for peri-patellar tendon sarcomas: case series. SpringerPlus 4, 740 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1510-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1510-9