Abstract

Background

Demyelinating plaques may induce headache through disruption of the pathways, which are implicated in the pathogeneses of migraine. We report a case of 25-year-old female patient, who presented with status migrainosus fulfilling the criteria of international classification of headache disorder. She was eventually diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) after an extensive work-up and long-term clinical and radiological follow-up.

Findings

At the onset of status migrainosus, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed the presence of several demyelinating lesions fulfilling Swanton criteria. She was started on migraine prophylactic treatment but there was no subsequent response. One year later, she presented with recurrent status migrainosus and a follow-up MRI revealed multiple gadolinium-enhancing lesions in the brain. She was treated with abortive migraine medications. Within the following 2 year, she developed ascending parasthesia and weakness of both lower limbs indicative of incomplete transverse myelitis in association with recurrent status migrainosus. A diagnosis of MS was established based on a follow-up MRI that satisfied the revised 2010 McDonald criteria. Both the headache and neurological signs improved with IV methylprednisolone therapy. Her headache entered remission after initiation of a disease modifying therapy.

Conclusion

Status migrainosus can be the initial presentation of MS. Unresponsiveness to migraine prophylactic therapy in the presence of active demyelinating plaque in MRI brain may pose a diagnostic challenge and a diagnosis of MS might be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) can cause various neurological symptoms depending on the location of demyelinating plaques (Putzki et al. 2009). Although the prevalence of migraine is threefold higher in MS patients compared to general population, headache is not typically considered as one of the symptoms of MS (Kister et al. 2010a; Noseworthy et al. 2000). Herein, we describe a young female patient who presented with status migrainosus as the initial presenting symptom of MS.

Case presentation

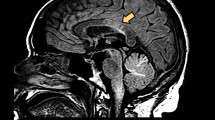

A 25-year-old female patient presented with severe, left parieto-temporal throbbing headache associated with nausea, vomiting and photophobia, which lasted for 7 days. Although she never had a previous history of headache, she continued to have recurring migraine headaches several times per week. Her headache fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of international classification of headache disorder, third edition (ICHD-3) (Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache S 2013). Her neurologic examination was unremarkable. At the time of the initial presentation, unenhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain showed subcortical and periventricular T2/Flair hyperintense lesions, with involvement of corpus callosum, left temporal lobe and right middle cerebellar peduncle fulfilling Swanton Criteria (Figure 1) (Swanton et al. 2006). She was diagnosed as migraine with radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS). She was started on topiramate as a prophylactic migraine therapy, which was subsequently discontinued due to poor response. She continued to use abortive medications (triptans & non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs “NSAIDs”) till her presentation with recurrent status migrainosus one year later. A follow-up MRI revealed multiple new T2/ flair hyperintense lesions in the brain and spinal cord indicative of radiological progression (Figure 2). A course of propranolol was initiated as alternative prophylactic migraine treatment but she continued to have recurrent severe headaches. A follow-up MRI brain with gadolinium, 6 months later, showed new T2/flair lesions in the periventricular, corpus callosal and juxtacortical areas along with new Gad-enhancing lesion at multiple supratentorial sites (Figure 3).

Follow-up MRI brain scans (April 2013) showed new T2/flair lesions in periventricular and juxtacortical regions with an increase in the overall lesion load when compared to the previous MRI scan as seen in the axial (a-c) and sagittal images (d-e). Enhanced Axial T1 MRI images showed five gadolinium-enhancing supratentorial lesions involving both hemispheres (f-h).

Within one year, the patient presented with one-week history of numbness and weakness of both lower legs and urgency of micturition in association with an attack of status migrainosus. Neurological examination showed bilateral pyramidal weakness of lower limbs, pathological brisk deep tendon reflexes and extensor plantars along with loss of vibration and pinprick sensation up to thoracic (T12) level. A follow-up MRI brain with gadolinium revealed multiple new enhancing lesions with an open-ring pattern (Figure 4). A lumbar puncture was performed and the cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed normal cell count, protein, and glucose. Oligoclonal bands were positive in the CSF and absent in the serum. Visual evoked potentials revealed delayed P100 wave latencies in both eye. However, somatosensory and brainstem evoked potentials were within normal limits. Autoimmune profile was unremarkable.

Follow-up MRI brain scans (March 2014) showed a significant increase in the lesion load involving the periaqueductal gray matter (a), periventricular and juxtacortical regions (b,c), corpus callosum, extending lesions to cortical areas (d,e) in both axial and sagittal T2/flair scans. Enhanced axial T1 MRI scans showed the presence of new gadolinium-enhancing lesions in the temporal, frontal and parietal lobes (f-h).

The patient was diagnosed with MS according to the revised 2010, McDonald criteria since she presented with incomplete transverse myelitis and after MRI showed dissemination in time and space (Polman et al. 2011). Her headache and neurological symptoms/signs improved significantly after a 5-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone. She was started on oral fingolimod 0.5 mg once daily as disease modifying therapy given her reluctance to use any injectable forms of medications. The headaches entered a remission phase for the next following months.

Discussion

Our case illustrates the association between the onset/ recurrence of status migrainosus with progressive T2/flair and new gadolinium enhancing demyelinating lesions on the initial and subsequent MRIs (1.5 Tesla field strength). The presence of demyelinating lesions at brainstem may explain the presentation of MS onset with migraine headache (Gee et al. 2005). Periaqueductal gray matter (PAG), located in the midbrain, is thought to be a key area in the pathogenesis of migraine. PAG acts as a rely station between cortical and brainstem structures and it modulates pain by providing an antinociceptive effect to the primary afferent system as well as influencing the autonomic and behavioral responses (Raskin et al. 1987). PAG has connections to the trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC), which runs from the medulla down into the region of the third cervical segment where it blends gradually into the cervical dorsal horns. Some refer to this region as the trigeminocervical complex (Ward 2012). Fibers from upper cervical roots enter the TNC, which sends fibers rostrally to the thalamus and collaterals to the autonomic nuclei in the brainstem and the hypothalamus. Thalamic neurons project to the somatosensory cortex but also to areas of the limbic system (Goadsby et al. 2002). A prevailing theory in the pathogenesis of the migraine attack is that hyperexcitability develops along the trigeminovascular pathway, probably facilitated by a dysfunction of the descending pain modulatory circuits (Raskin et al. 1987; Ward 2012; Goadsby et al. 2002).

The causal relationship between migraine and MS, in our case, was suggested by the subsequent improvement of headache with a DMT. On the other hand, a response to corticosteroids such as methylprednisolone does not necessarily this causal relationship as both conditions may show improvement with the use of corticosteroids. Both migraine and MS are relatively common in young females and both may accidentally co-exist. The prevalence of migraine in patients with MS is between 20% to 45% (Kister et al. 2010b). The diagnosis of migraine precedes MS in most cases (Kister et al. 2010a; Fragoso & Brooks 2007; Yetimalar et al. 2008; Villani et al. 2008) and it is suggested to be a presenting symptom of MS (Kister et al. 2012; Zorzon et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2013). Freedman et al. reported migraine headache at MS onset in 18 (1.6%) out of 1113 patients with MS and an additional 26 (2.3%) patients experiencing recurrent headaches at the time of MS exacerbation, often accompanied by posterior fossa signs (Freedman & Gray 1989).

Migraine and MS share several features. Both have a relapsing-remitting course affecting the central nervous system with occasional chronic evolution, more prevalent in women of childbearing age, and both appear to be influenced by hormonal changes; i.e., less exacerbations throughout the first two trimesters of pregnancy (Kister et al. 2010b).

The mechanism behind the association of MS and migraine is debatable and several hypotheses were introduced. First, headache may be induced by the inflammatory demyelinating MS lesions by disrupting the pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of migraine (Kister et al. 2010b). It was observed that lesions within the midbrain especially in the PAG were commonly associated with comorbid migraine in MS patients (Gee et al. 2005; Tortorella et al. 2006). It should be noted that the inflammatory process caused by demyelination is not necessarily the cause of headaches given the incidental co-existence of both conditions. Second, a dysregulation of the serotoninergic system caused by demyelinating lesions has been linked to the headache exacerbation (Sandyk & Awerbuch 1994). Third, cortical demyelination has been shown to accelerate cortical spreading depression, which is a key mechanism in migraine pathophysiology (Merkler et al. 2009). Although cortical demyelinating plaques were seen in our case (Figure 4d,e), it is often difficult to detect definitive cortical involvement given the low sensitivity of conventional MRI. Finally, it is suggested that migraine with aura may be associated with MS activity since the development of aura involves activation of matrix metalloproteins resulting in subtle increase in permeability of the blood–brain barrier and thus presumptive neuro-inflammation (Gursoy-Ozdemir et al. 2004). Kistar et al. proposed that certain privileged central nervous system compartment to circulating T cells may be sensitized during migraine aura (Kister et al. 2010b).

Conclusion

Status migrainosus in the presence of demyelinating MRI features at the initial presentation may pose diagnostic dilemma. Failure to respond to prophylactic migraine therapy in view of progressive demyelinating features on follow-up MRIs may point to another relatively common neurological disorder such as MS among young women.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Fragoso YD, Brooks JB (2007) Two cases of lesions in brainstem in multiple sclerosis and refractory migraine. Headache 47(6):852–854

Freedman MS, Gray TA (1989) Vascular headache: a presenting symptom of multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurol Sci 16(1):63–66

Gee JR, Chang J, Dublin AB, Vijayan N (2005) The association of brainstem lesions with migraine-like headache: an imaging study of multiple sclerosis. Headache 45(6):670–677

Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD (2002) Migraine–current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med 346(4):257–270

Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Qiu J, Matsuoka N, Bolay H, Bermpohl D, Jin H, Wang X, Rosenberg GA, Lo EH, Moskowitz MA (2004) Cortical spreading depression activates and upregulates MMP-9. J Clin Invest 113(10):1447–1455

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache S (2013) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 33(9):629–808

Kister I, Caminero AB, Monteith TS, Soliman A, Bacon TE, Bacon JH, Kalina JT, Inglese M, Herbert J, Lipton RB (2010a) Migraine is comorbid with multiple sclerosis and associated with a more symptomatic MS course. J Headache Pain 11(5):417–425

Kister I, Caminero AB, Herbert J, Lipton RB (2010b) Tension-type headache and migraine in multiple sclerosis. Curr Pain Headache Rep 14(6):441–448

Kister I, Munger KL, Herbert J, Ascherio A (2012) Increased risk of multiple sclerosis among women with migraine in the Nurses' Health Study II. Mult Scler 18(1):90–97

Lin GY, Wang CW, Chiang TT, Peng GS, Yang FC (2013) Multiple sclerosis presenting initially with a worsening of migraine symptoms. J Headache Pain 14:70

Merkler D, Klinker F, Jurgens T, Glaser R, Paulus W, Brinkmann BG, Sereda MW, Stadelmann-Nessler C, Guedes RC, Bruck W, Liebetanz D (2009) Propagation of spreading depression inversely correlates with cortical myelin content. Ann Neurol 66(3):355–365

Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG (2000) Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 343(13):938–952

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, Fujihara K, Havrdova E, Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Lublin FD, Montalban X, O'Connor P, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Thompson AJ, Waubant E, Weinshenker B, Wolinsky JS (2011) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 69(2):292–302

Putzki N, Pfriem A, Limmroth V, Yaldizli O, Tettenborn B, Diener HC, Katsarava Z (2009) Prevalence of migraine, tension-type headache and trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 16(2):262–267

Raskin NH, Hosobuchi Y, Lamb S (1987) Headache may arise from perturbation of brain. Headache 27(8):416–420

Sandyk R, Awerbuch GI (1994) The co-occurrence of multiple sclerosis and migraine headache: the serotoninergic link. Int J Neurosci 76(3–4):249–257

Swanton JK, Fernando K, Dalton CM, Miszkiel KA, Thompson AJ, Plant GT, Miller DH (2006) Modification of MRI criteria for multiple sclerosis in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 77(7):830–833

Tortorella P, Rocca MA, Colombo B, Annovazzi P, Comi G, Filippi M (2006) Assessment of MRI abnormalities of the brainstem from patients with migraine and multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 244(1–2):137–141

Villani V, Prosperini L, Ciuffoli A, Pizzolato R, Salvetti M, Pozzilli C, Sette G (2008) Primary headache and multiple sclerosis: preliminary results of a prospective study. Neurol Sci 29(Suppl 1):S146–S148

Ward TN (2012) Migraine diagnosis and pathophysiology. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 18(4):753–763

Yetimalar Y, Secil Y, Inceoglu AK, Eren S, Basoglu M (2008) Unusual primary manifestations of multiple sclerosis. N Z Med J 121(1277):47–59

Zorzon M, Zivadinov R, Nasuelli D, Dolfini P, Bosco A, Bratina A, Tommasi MA, Locatelli L, Cazzato G (2003) Risk factors of multiple sclerosis: a case–control study. Neurol Sci 24(4):242–247

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the patient in accepting to include her clinical and radiological information for publication in order to enlighten the readers for the unusual presentation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RA, SA, RK and JA were involved in the diagnosis and treatment of the case report. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alroughani, R., Ahmed, S.F., Khan, R. et al. Status migrainosus as an initial presentation of multiple sclerosis. SpringerPlus 4, 28 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0818-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0818-9