Abstract

The recent home bias is primarily related to the equity bias as measured by the international capital asset pricing model (CAPM); this measure has declined over the past two decades amid financial globalization, but remains high in most developed countries. The key to understanding this puzzling phenomenon lies in how accurately this indicator can be predicted. In this paper, we propose to use the savings retention coefficient estimated by the Feldstein–Horioka (F–H) regression as a cross-country measure of home bias. We re-estimate the savings retention coefficient based on an estimation model in which the FH regression is embedded in the model derived from Tobin's q-theory of saddle-road dynamics of investment under convex adjustment costs. We then use dynamic panel estimation to estimate the new measure in OECD countries. The main empirical results are as follows. The new measure of home country bias, such as the equity bias measure, declined steadily until 2008, but recovered to the level of the 60 s and 70 s after the 2008 financial crisis. Interestingly, people expected home country bias to be very high after the financial crisis, but in fact it simply returned to its previous level.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In their controversial paper, Feldstein and Horioka (1980; hereafter FH) examined the relationship between the GDP share of domestic investment and the GDP share of domestic savings in a single regression analysis (FH regression) for 21 OECD countries. Their empirical studies showed that the estimated correlation, which was within 0.85–0.95, was remarkably high across countries. They interpreted their findings as indicating a high degree of financial frictions and concluded that they were inconsistent with the assumption of perfect capital mobility commonly used in studies of international finance. The idea is this. Under perfect capital mobility, if a country has excess domestic investment, capital flows will come from countries with excess savings, and vice versa. In other words, domestic investment will be uncorrelated with domestic saving. On the contrary, the FH regression showed a very high correlation. This problem is often referred to as the "Feldstein–Horioka puzzle" (FHP). Although the FHP is old, it is still an important issue. I will leave earlier research on the FHP to a detailed survey by Coakley et al. (1998), and Apergis and Tsoumas (2009) for relatively recent research.

On the other hand, many recent studies report that, despite the globalization of financial markets, investors have failed to reap its potential benefits, favoring domestic assets over international positions in their investment portfolios. This bias, known as the equity home country bias (EHB), is another major puzzle in financial economics. The measure of EHB is commonly defined as follows:

The two issues are obviously closely related, since they are based on the idea that "financial globalization" has lowered barriers to international trade in financial assets and international capital flows. I have proposed here a new measure of home country bias. In a completely different approach from the international CAPM of previous empirical studies, I propose the following new measure:

where Corr. stands for the correlation.

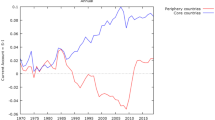

In a world without financial market frictions, the international capital asset pricing model (CAPM) with homogeneous investors across the world predicts that the representative investor of a given country should hold the world market portfolio. In other words, if the EHB for country i (EHBi) is zero, the portfolio is optimally diversified along the international CAPM. Bekaert and Wang (2009) report that in the case of equities, the global average EHB was around 0.63. It has declined in the last two decades in the process of financial globalization, but remains high. A major drawback of the EHB is that it does not cover a wide range of financial asset holdings. Similar to FHP, a growing body of research examines the determinants of the EHB. Coeurdacier and Rey (2012) review the large body of research on the EHB in terms of (i) hedging motives in frictionless financial markets, (ii) asset transaction costs in international financial markets, and (iii) information frictions and behavioral biases. They refer to macroeconomic modeling that incorporates international portfolio choice as open economy financial macroeconomics. As reported in Bekaert and Wang (2009), these studies additionally propose transaction costs, real exchange rate risk, information barriers, corporate governance issues, and lack of familiarity as determinants. Because the causes of home bias are diverse, complex, and still unresolved, we focus here only on estimating an accurate measure of home bias.

That is, we estimate the home country bias as the slope coefficient β of the FH regression using ordinary least squares, called the "savings retention rate." This is considered the home country bias indicator (HBMi) in country i. This measure varies between zero and one. When it is zero, the savings–investment correlation is zero and there are complete capital flows; when it is one, the savings–investment correlation is perfect and there are no capital flows. Since the actual savings retention rate lies between 1 and 0, it can be considered an indicator of HBM. Note that the estimation of HBM faces some estimation biases, as discussed in much of the literature, which will be discussed below. To avoid this, I start to set up a representative firm’s investment behavior model, which was developed by Abel (1982), Hayashi (1982), and Summers et al. (1981) based on Tobin’s q theory. According to the System of National Accounts (SNA), gross domestic investment (GDI) comprises housing, gross private, and public investments. Among them, gross private investment predominates and plays a crucial role in GDI behavior. Therefore, I first addressed the investment behavior of a representative firm based on the saddle dynamics of investment under convex adjustment costs. Then, a dynamic panel estimation model was derived by embedding the savings retention rate: the slope coefficient beta, into the optimal investment process of the firm. We then apply dynamic panel estimation to measure the savings retention rate, the HBM in OECD countries rather than in individual countries, such as the EHB. Thus, country-specific indices are removed. Since domestic savings cover a wide range of financial asset holdings, the HBM can capture the intensity of home bias and can be considered a comprehensive measure of home bias in OECD countries. Since optimal investment behavior involves lagged investment variables, a dynamic panel regression method was used to avoid strong endogeneity problems.Footnote 1

The main results are as follows: except for the financial bubble period from 2000 to 2008, the HBM, which had steadily declined from 0.5 to 0.3 until 2000, as indicated by the EHB measured by the CAPM, returned to its previous home bias measure of 0.5 after the 2008 financial crisis. In other words, people expected the HBM to be very high after the financial crisis, but in fact it only returned to the persistent levels of the 60 s, 70 s, and 80 s.

The sections are organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents a theoretical model of the investment behavior of a representative firm. We derive an estimation model by solving the firm's optimization problem. A dynamic panel estimation model is obtained by embedding the relationship between the domestic investment share and the domestic savings share in the firm's optimal investment process expressed by the FH regression in Sect. 2.1. We also describe the data used here and apply two types of panel unit root tests in Sect. 2.2. We run dynamic panel regressions with four different specifications to estimate the measure of home bias as indicated by the savings retention rate in Sect. 2.3. Section 3 reports and discusses the estimation results. Section 4 provides a brief discussion on the results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Theory and estimation equation

Consider the following optimal problem (P) of the investment behavior of representative firms in country i, developed by Abel (1982), Hayashi (1982), and Summers et al. (1981) on the basis of Tobin's q theoryFootnote 2:

where \({r}_{i}\) is the discount rate (0 < \({r}_{i}\) < 1),\({R}_{i}({k}_{it}\)\()\) is the revenue function,\({I}_{it}\) is the gross investment a\({C}_{i}({k}_{it}\)\()\) is the adjustment cost function, and i is the country index.

The problem implies that the representative firm chooses its level of investment so as to maximize the total discounted pure revenue flow, where investment increases the capital stock and raises revenues, but it pays the costs of investment adjustment as well as the investment itself.

2.1 Estimation equation

In this section, by demonstrating the saddle point stability of the model and assuming that the estimation coefficients are the same across countries, we derive the following equation for estimating investment shares, as shown below:

where \({\widetilde{I}}_{it} ({\widetilde{S}}_{it})\) is the domestic investment (saving) share of country i in period t.

The derivation of the estimation equation is explained intuitively here. I have left the detailed derivation in Appendix. In addition, to avoid complications, country-specific indicators are temporarily removed from the variables. Applying the standard solution method to the optimization problem (P), the Euler equation is derived as a necessary condition for optimality. We can also show that the transversality conditions are satisfied. The linearization of the Euler equation near the optimal steady state shows the saddle point stability. That is, there are two distinct positive real roots, and one of the two roots has an absolute value less than one. Furthermore, saddle-point stability implies that the optimal path should be on a stable path, otherwise it will diverge and eventually violate optimality. To estimate the savings retention coefficient beta, we do not directly estimate the firm's investment function, but rather use the saddle-point stability property of the optimal accumulation path.

Let \({\lambda }_{1}\) be the root satisfying \(0<{\lambda }_{1}<1\). Subsequently, the optimal path should be on a stable path, other than that it diverges. Therefore, the optimal path is expected to satisfy the following difference equations:

From Eq. (2), subtraction to eliminate \({k}^{*}\) gives

From the capital accumulation equations, it follows that

Combining both relations will readily give the difference equation:

Finally, we obtain the following equation along the saddle-point path as the optimal investment behavior:

Equation (3) must then be rewritten in terms of the GDP share originally used in FH (1980). To do so, I assume that a country's average GDP growth rate over the observation period, denoted by \(g\), is a constant average growth rate over the observation period and \(0 < g < 1\). In fact, the average GDP growth rate for OECD countries has been stable at around 0.02–0.04 (2–4%) over the past 40 years, supporting this assumption.

Dividing both sides by regarding \({Y}_{t}={GDP}_{t}\) gives

Because \({Y}_{t+1}=(1+g){Y}_{t}\), the following theoretical model will be obtained:

Finally, taking the country indices of the variables again and assuming that the coefficients are common across countries, it follows that

, where \({\beta }_{0}=\frac{(1+{\lambda }_{1i})}{(1+{g}_{i})}\mathrm{\,and\,}{\beta }_{1}=\frac{{\lambda }_{1i}}{{(1+{g}_{i})}^{2}}\).

Due to the definition of the home country bias measure defined in the introduction, the FH regression satisfies; \({\widetilde{I}}_{it}=\alpha +\beta {\widetilde{S}}_{it}\) it follows that

Combining Eqs. (4) and (5) finally yields the following estimation equation:

Since \(0 <{\lambda }_{1}< 1\) holds, it follows that the sign conditions of Eq. (1) imply that \((i) 0<{\beta }_{0}\), \((ii) -1<{\beta }_{1}<0\), and \({(iii) \beta }_{2}={-\beta }_{3}\) should hold.

Adding disturbance terms to Eq. (1) yields the following dynamic panel regression equation:

where i = country index, t = time index, \({\widetilde{I}}_{it}\) is the domestic investment share of GDP, \({\widetilde{S}}_{it}\) is the domestic saving share of GDP, \({u}_{it}\) is the error term (shocks and effect of frictions), and \({\gamma }_{i}\) is the a specific effect of the country.

We continue to assume that the coefficients are the same across countries and that country-specific shocks are included in \({\gamma }_{i}\). Note that the deterministic part of the above model is derived based on the investment model of a fully rational firm; therefore, the error term indicates the impact of the various fundamental shocks and capital market frictions.

Note also that the signs of the coefficients in (7) must satisfy the following constraints (CI) and (CII) of the theoretical model described in Sect. 2.1.

(CI) \({\beta }_{0}\) and \({\beta }_{1}\) statistically significant and satisfy \((i) 0<{\beta }_{0}\) and \((ii) -1<{\beta }_{1}<0\).

(CII) \({\beta }_{0}\) and \({\beta }_{1}\) statistically significant, and \({(iii) \beta }_{2}={-\beta }_{3}.\)

If (CII) does not hold, then the estimates should not be considered as those of the savings retention coefficient (β). As mentioned earlier, β is a clear index of the HBM that indicates the impact of the domestic savings rate on domestic investment behavior.

2.2 Estimation methods

The regression equation (7) includes lagged dependent variables as independent variables, as well as the country-specific effect. As a result, standard ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation is highly biased. To circumvent this problem, we apply dynamic panel estimation (DPE), developed by Arellano and Bond (1991) and Arellano and Bover (1995), under the condition that all estimators are stationary. Four specifications of DPE are used for each data set: one-step difference GMM, two-step difference GMM, one-step system GMM, and two-step system GMM.

A brief description of these estimation methods is given in Appendix. Although they are powerful, one should be wary of weak instruments and overidentification problems. Indeed, DPEs are known to easily generate a large number of instruments. To check for these problems, two important statistics are reported in the results. For the weak instrument problem, the Arellano–Bond AR(1) test (A–B AR(1)) and the Arellano–Bond AR(2) test (A–B AR(2)) for the first and second serial correlations are reported; for the overidentification problem, the Hansen test for overidentification of instruments is reported. To avoid the weak instrument problem, the A–B AR(1) test must reject the null hypothesis of "no serial correlation". Conversely, for the A–B AR(2) test, the null hypothesis must be accepted. For the overidentification problem, the null hypothesis of "no overidentification" must be accepted for the Hansen J test. For the GMM system, the result of the difference-in-Hansen test was reported for the validity of the additional moment restriction. After checking these diagnostic tests, the estimates must satisfy the sign condition (CI). The Wald test was then applied to examine the test condition (CII). In the end, the estimates that pass all of the above diagnostic tests are selected.

I estimated the following four cases, and the results are reported in Table 2 through Table 7.

Case 1: Exact replication of the FHP estimation

Data: Gross national investment GDP share and gross saving GDP share

Period: 1960–1974

Countries: 21 OECD countries

Case 2: Replication studies of the FHP estimation

Data: Gross national investment GDP share and gross saving GDP share

Period: 1960–1974

Countries: 28 OECD countries

Case 3: Ten-year sub-samples

Data: Same as Case 2

Period: 1960–1969, 1970–1979, 1980–1989, 1990–1999

Countries: 28 OECD countries

Case 4: Breaks in 2000s.

Data: Same as Case 2

Period: 2000–2008, 2009–2014, 2000–2014

Countries:28 OECD countries

Cases 1 and 2 were implemented only to compare our results with the original FH (1980) results and to shed light on the long-term controversies of the FHP.

2.3 Data and stationarity

All data were extracted from the national accounts in Penn World Table Ver. 9. The derivation of the gross domestic investment share, the gross domestic saving share, and the economic openness index is explained in detail in Appendix. Note that the economic openness index was used only as a standard instrumental variable, not as a GMM instrument variable. Two panel data sets were constructed. One was an annual panel data set consisting of 21 countries from 1960 to 2014 to examine only Case 1 and replicate the original regression of FH (1980), and the other was an annual panel data set consisting of 28 countries for the same period to examine Cases 2 to 4. Each data set is a balanced panel data set.

One of the key assumptions for the application of DPE is the stationarity of the series. To investigate this, the first- and second-generation panel unit root tests were conducted. Although we did not report the results table of the first-generation panel unit root tests in this study, five different first-generation panel unit root tests were conducted during the estimation period (1960–2014): the Levin-Lin-Chu, Harris-Tzavalis, Breitung, Im-Pesaran-Shin (IPS), and Fisher-type panel unit root tests. As shown by Hlouskova and Wagner (2006), the performance of the Hadri-LM unit root test is poor; therefore, it was not run here. As a result of the test, both the null hypothesis that the panel has a unit root and the null hypothesis that all panels have a unit root were strongly rejected for the panel data of 28 countries. However, for the panel data of 21 countries, the test results were mixed, especially for the series of domestic saving shares.

Since country-specific data were used here, we need to pay attention to correlations across countries. Therefore, the second-generation panel unit root test proposed by Pesaran (2007), called cross-sectionally augmented IPS (CIPS), was repeated with three different ADFs for each estimation period from Case 1 to Case 4, and the results are presented in Table 1.

Because the critical value of the t-statistic varies depending on the type of ADF, as noted in the notes to Table 1, the results of the hypothesis tests at the 10%, 5%, and 1% significance levels are indicated only by an asterisk. According to Table 1, the two main series \(\left({\widetilde{I}}_{it},{\widetilde{S}}_{it}\right)\) were stationary overall, although some tests were rejected at the 10% significance level. However, the estimates from 2000 to 2014 in case 4 may be spurious, as the domestic savings series were not stationary in any of the three ADF types. We should be cautious about this case.

3 Estimation results

One-step and two-step difference GMMs were used. To capture changes in economic structure, only the economic openness index (eco_open) was used as a standard instrumental variable, following FH (1980). In this section, the estimation results for cases 1 to 4 are discussed as follows.

3.1 Replications of FH estimations

We examine the HP estimates for cases 1 and 2. We examine the HP estimates for cases 1 and 2.

3.1.1 Case 1

Table 2 reports the exact results of the 21-country replication estimation for case 1. For this case, I applied one-step and two-step difference GMMs with collapsed instruments, with and without a constant term. The results are reported in columns (1) and (3), and the one- and two-step system GMMs are reported in columns (2) and (4), respectively, of Table 2. The Arellano–Bond AR(1) and AR(2) tests showed a weak instrument problem for columns (1) to (4). All overidentification test results were satisfactory. Since column (3) of Table 2 satisfied the sign condition (CI), I chose it as our estimate for case 1. As a result, the estimated beta is 0.71, which is still large but slightly smaller than the FH estimate of 0.89–0.95. However, it should be noted that this estimate has some bias due to the weak instrument problem. Thus, the conclusion is that there were no robust estimates in the exact replication case 1.

3.1.2 Case 2

The replication estimation for 28 countries is done in the same way as in case 1. The results for case 2 are presented in Table 3. For this case, I used one- and two-stage differences GMMs with collapsed instruments, with and without a constant term. The results are reported in columns (1) and (3) of Table 3, and the one- and two-step system GMMs are reported in columns (2) and (4) of Table 3, respectively. The Arellano–Bond AR(1) and AR(2) tests showed a weak instrument problem for columns (1) and (2). All overidentification test results were satisfactory. Column (3) of Table 3 was selected as our benchmark result of the case, because all sign conditions i) through iii) derived from the theoretical model were satisfied. As a result, the estimate of the HBM reproduced in this case was 0.52, which was much smaller than FH's original estimate: 0.89–0.95. Since all the statistical requirements were well met, we choose 0.52 as the benchmark value for the estimated HBM in the replication period.Footnote 3

3.2 HBM estimates in cases 3 and 4

We continue estimating HBM in cases 3 and 4 here.

3.2.1 Case 3

The estimation results are presented in Table 4, columns (1) to (3), where a one-step difference or one-step system GMM is applied. For the observation period of the 1990s, the one-step system GMM was applied, as reported in column (4) of Table 4. In addition, the two-step system GMM was applied to case 2. The results are shown in Table 5. For the results of columns (2) and (3) in Table 4, the sign of is not statistically significant. Consequently, the estimates of beta in columns (2) and (3) are not considered as savings retention coefficients, as discussed earlier. In contrast, in Table 5, conditions (i) and (ii) on the sign of the coefficients are all satisfied. Condition (iii) is also satisfied, except for the estimates in column (3). Thus, overall, the required sign conditions (CI) and (CII) are satisfied and robust. In addition, the tests for weak instrument and overidentification yielded positive results. In summary, our test statistics indicate a proper specification.

Table 6 summarizes the HBM estimates measured over a 40-year period. The table shows that the beta values were almost the same in the 1960s and 1970s, but declined significantly in the 1980s and 1990s. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Georgopoulos and Hejazi (2005) and But and Morley (2017). This may be partly due to the opening up of the economy and financial market integration in the 1980s and 1990s, which led to increased capital mobility and a decline in HBM.

3.2.2 Case 4

We estimated the HBM not only for the entire observation period 2000–2014, but also for two subperiods, 2000–2008 and 2009–2014. The main reason for using 2008 as the breakpoint year was the financial crisis of 2008. Table 7 reports the estimation results from 2000 to 2014 with 2008 as the breakpoint year. All of the estimates are statistically significant. It is important to note that the estimates were insignificant before the breakpoint year and then became significant again after the breakpoint year. The estimates in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7 show that they became insignificant over the period 2000–2008. In other words, one could say that the home country bias temporarily disappeared during this period. In addition, it is very interesting to note that the period in which the home bias disappeared coincided with a period of a global financial bubble (2000–2008). This implies that the declining trend of the HBM continued in 2000–2008. Indeed, Coeurdacier and Rey (2012) calculate the EBH separately for cross-border bonds, cross-border bank loans, and cross-regional bank assets and find that all three measures of home bias declined between 1999 and 2008. In contrast, column (3) of Table 7 shows that the relationship between savings and investment returns after 2008, with an estimated HBM of 0.51, is similar to that in the 1960s and 1970s. Interestingly, But and Morley (2017) report a similar fact. As mentioned above, the series of the domestic saving share was non-stationary between 2000 and 2014, so the result in column (4) of Table 7 may be spurious.

In summary, the empirical results reported in Table 2 through Table 7 are as follows.

-

A.

An exact replication of the FHP in 21 OECD countries during 1964–1974 yielded an estimate of 0.71, high enough to support the FH result, but with some bias due to weak instrument problems.

-

B.

Replication of the FHP in the 28 OECD countries during 1964–1974 yielded an estimated HBM of 0.52, which was much smaller than the FH (1980) estimate of 0.89.

-

C.

Estimates using samples for every 10 years during 1960–1999 showed that the HBM gradually decreased from 0.57 to 0.32.

-

D.

From 2000 to 2014, the estimated HMB was not statistically significant from 2000 to 2008. It was only after 2008 that it became statistically significant, with an estimated HBM of 0.51 from 2009 to 2014, which is comparable to that of the 1960s and 1970s.

4 Discussion

Our results A) through D) above have the following three important implications. A) and B) implies that the robust estimate of the HBM is 0.52, which is much lower than the 0.89 of the originally estimated by FH (1980). C) shows that the HBM has declined steadily from 0.52 to 0.33 over the last four decades until 2000. Furthermore, D) shows that the correlation between savings and investment temporarily disappeared during the era of globalization and the financial bubble years from 2000 to 2008. The HBM turned 0.51 from 2009 to 2014. These results clearly indicate that despite the fact that globalization has accelerated the integration of international financial markets in recent decades, the home country bias is still significant from 2009 to 2014 in OECD countries. The last fact is particularly interesting: the home bias had been declining steadily until 2008, but after the 2008 financial crisis, it returned to the HBM of 0.5. In other words, after the financial crisis, people expected the home bias measure to be very high, but in fact it ended up returning to the levels of the '60 s and '70 s.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we have focused on investigating the home country bias puzzle: although recent financial globalization has lowered barriers to international trade in financial assets and international capital flows, we still observe relatively high home country bias in advanced countries. The EHB based on the international CAPM supports this for equities. Indeed, the EHB measure showed that it had declined over the past two decades and was about 0.63 globally. However, it was unclear whether this was true for a wide range of financial assets beyond equities. To investigate this issue, we introduced the HBM based on the FH regression. Note that since we use the country's domestic saving, it includes all types of asset holdings. We show that in OECD countries, the HBM declined over the four decades until the 2008 financial crisis and returned to 0.50 after the crisis. Our estimation results clearly support those of the EHB (Table 7).

Finally, we leave the study of the main source of home bias to other studies, but to determine this, we need to investigate how each economic factor affects the savings retention coefficient. A promising econometric approach would be to apply the dynamic panel threshold analysis proposed by Seo and Shin (2016). This should be on the agenda for future research.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the results of this study and the estimation program are available in the STATA format in the supplementary file to this publication.

Notes

For example, Arellano and Bond (1991) develop the dynamic panel analysis to examine the relationship between employment and wages, which has strong endogeneity.

A similar model is analyzed in Ch. 9, Romer (2012).

The estimated value of 0.52 happens to coincide with the value obtained by the calibration of Bai and Zhang (2010).

\(\overline{k }\) is the maximum reproducible capital when \(\overline{I }\) is given.

References

Abel AB (1982) Dynamic effects of permanent and temporary tax policies in a q model of investment. J Monet Econ 9:353–373

Apergis N, Tsoumas C (2009) A survey of the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle: What has been done and where we stand. Res Econ 63:64–76

Arellano M, Bond SR (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58:277–279

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics 68:29–51

Bai Y, Zhang J (2010) Solving the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle with financial frictions. Econometrica 78:603–632

Baltagi B (2018) Econometric analysis of panel data, 4th edn. John Wiley and Sun West Sussex, UK

Bekaert G, Wang XS (2009) Home bias revisited. SSRN 1344880.

But B, Morley B (2017) The Feldstein-Horioka puzzle and capital mobility: the role of the recent financial crisis. Econ Syst 41:139–150

Coakley J, Kulasi F, Smith R (1998) The Feldstein-Horioka puzzle and capital mobility: a review. Int J Financ Econ 3:169–188

Coeurdacier N, Rey H (2012) Home bias in open economy financial macroeconomics. J Econ Lit 51(1):63–115

Feldstein M, Horioka C (1980) Domestic saving and international capital flows. Econ J 90:314–329

Georgopoulos GJ, Hejazi W (2005) Feldstein-Horioka meets a time trend. Econ Lett 86:353–357

Hayashi F (1982) Tobin’s marginal q and average q: a neoclassical interpretation. Econometrica 50:213–224

Hlouskova J, Wagner M (2006) The performance of panel unit root and stationarity tests: results from a large scale simulation study. Economet Rev 25:85–116

Pesaran MH (2007) A simple panel unit root test. J Appl Economet 22:265–321

Romer D (2012) Advanced macroeconomics, 4th edn. McGrow-Hill Irwin, New York

Seo M, Shing Y (2016) Dynamic panel with threshold effect and endogeneity. J Economet 195:169–186

Summers LH, Bosworth BP, Tobin J, White PM (1981) Taxation and corporate investment: a q-theory approach. Brook Pap Econ Act 1981:67–127

Acknowledgements

The Article Processing Charge was covered by the funds of PAPAIOS and JSPS (KAKENHI Grant Number JP 21HP2002). The previous version was presented at the 6th International Conference on Economic Structures (PPAIOS-ISES2022). I would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments. Taisei Ogawa, former graduate student at the Graduate School of Economics, Meiji Gakuin University, helped me with this research. I am grateful for the valuable comments of Yan Bai at the University of Rochester and the participants of the seminars at GREQAM, Dalhousie University, and Kobe University. Finally, I dedicate this work to the late Professor Mitsuhiko Satake of Doshisha University.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the Research Institute of Business and Economics at the Meiji Gakuin University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Data

See Table 8.

This appendix provides a detailed description of the data used in the study. All the data used in this section were extracted from the national accounts data contained in the Penn World Table Ver. 9.0 (www.ggdc.net/pwt).

-

The variable series codes used in the estimation are defined as follows.

The important variables are obtained as follows:

-

Gross domestic saving share(\(\widetilde{S}\)): v_srate = (v_gdp – v_c – v_g)/v_gdp

-

Gross domestic investment share (\(\widetilde{I}\)): v_irate = v_i/v_gdp,

-

Index of economic openness: eco_open = (v_x + v_m)/v_gdp.

-

The 21 OECD countries are Australia (AUS), Austria (AUT), Belgium (BEL), Canada (CAN), Switzerland (CHE), Germany (DEU), Denmark (DNK), Spain (ESP), Finland (FIN), France (FRA), UK (GBR), Greece (GRC), Ireland (IRL), Italy (ITA), Japan (JPN), Luxembourg (LUX), Netherlands (NLD), Norway (NOR), New Zealand (NZL), Sweden (SWE), (USA).

-

The 28 OECD countries are the above 21 countries + the following 7 countries: Chili (CHL), Iceland (ISL), Israel (ISR), Korea (KOR), Mexico (MEX), Portugal (PRT), Turkey (TUR).

1.2 Mathematical derivation

To derive the estimation equation (1) in Sect. 2.1, we first make the following assumptions. To avoid further complications, country indices are removed from the variables. We start with the following basic assumptions.

Assumption A1.

\(C(I)\) is \({C}^{2}\) on the interval \(\left(0, \overline{I }\right)\) and strictly convex, where \(\overline{I }\) is the upper bound of investment. Moreover, \(\underset{I\to \overline{I}}{\mathit{lim} }C (I)=\underset{I\to \overline{I}}{\mathit{lim} }C^{\prime} (I)=\infty\,and\,C^{\prime}(0)=0.\)

Assumption A2.

\(R(k)\) is \({C}^{2}\) defined on\(\mathfrak{F}\equiv \left(0, \frac{\overline{I}}{\delta }\right)=(0, \overline{k })\), and strictly concave with respect to k.Footnote 4

We rewrite the problem using the following objective function as defined below to solve the problem.

Definition A1.

\(V({k}_{t-1},{k}_{t})\equiv R({k}_{t})-{I}_{t}-C({I}_{t})=R({k}_{t})-({k}_{t}-(1-\delta ){k}_{t-1})-C({k}_{t}-(1-\delta ){k}_{t-1}) (t\ge 1)\)

Using the redefined objective function, the original problem (P) is rewritten as follows.

From the rewritten optimal problem (P’), the following Euler equations can be derived quickly.

From the Euler equation (8), the optimal steady state is defined as shown below.

Definition A2.

The optimal steady state \(k^{*}\) is a solution of the following equation.

Because of Assumption 1, there exists an upper-bound \(\overline{k} = {\raise0.7ex\hbox{${\overline{I} }$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\overline{I} } \delta }}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$\delta $}} > k_{t} > 0\,(t \ge 0).\)It follows that \(\underset{t\to \infty }{\mathit{lim}}{(1+r)}^{-t}{k}_{t}<\underset{t\to \infty }{\mathit{lim}}{(1+r)}^{-t}\overline{k }=0\). Therefore, the transversality condition holds. As a result, it is expected that any optimal path will satisfy this condition.

Furthermore, to study the local stability around the steady state \({k}^{*}\), let us linearize the Euler equations around \({k}^{*}\). After some calculations, we get the following:

, where \({Z}_{t}={k}_{t}-{k}^{*}\).

Using Definition A1 and calculating each second-order partial derivative evaluated at \({k}^{*}\), Eq. (9) can be rewritten as follows.

where the symbol “*” denotes that the functions are evaluated in the optimal steady state \({k}^{*}\). Then, further simplification will yield the following second-order characteristic equation \(f(\lambda )=0\) related to the Euler equation:

We then prove the following important proposition. Based on this, we will derive the estimation equation.

Proposition.

If \(f(1)<0\) and \(f(0)>0\) hold, then the steady state \({k}^{*}\) is saddle-point stable.

Proof.

Note that \(f(0)=(1+r)>0\) already holds. Therefore, I need show that \(f(1)<0\) will also hold. Equation (10) quickly provides the following relation:

Thus, the required property is established. ■

The proposition implies that there are two positive real roots and that one of the two roots has an absolute value less than one. As claimed before, the transversality conditions are satisfied. Thus, saddle-point stability implies that the optimal path should lie on stable linear manifolds. Otherwise, such paths would diverge and ultimately be inconsistent with optimality. For our estimation of the savings retention coefficient, namely, the HBM, we use the saddle-point stability property of the optimal accumulation path instead of estimating the firm's investment function directly.

Let \({\lambda }_{1}\) be the root satisfying \(0<{\lambda }_{1}<1\). Then, the optimal path is expected to satisfy the following difference equations:

This finally derives Eq. (2) in Sect. 2.1.

1.3 Estimation methods

The estimation methods used are briefly described here. A detailed explanation can be found in Baltagi (2018). To keep our explanation as simple as possible, let us consider the following simple regression equation instead of Eq. (1):

If we take one lag in the equation and subtract it from the equation above to eliminate fixed effects, we get the following.

Note that the following moment conditions hold:

, where 0 is a zero-column vector and.

Arellano and Bond (1991) suggest that using \({{\varvec{Z}}}_{i}\) and constructing the following weight matrix:

Then we conduct the GMM estimate for the regression equation(1). This estimator is called the one-step difference GMM. The elements of the vector \({{\varvec{Z}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\) are called the GMM-type instruments. Note that other exogenous variables can also be included in this vector \({{\varvec{Z}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\), and these are called standard instruments. Furthermore, if the matrix \({\varvec{H}}\) is replaced with the estimation error vector: \(\widehat{{{\varvec{\varepsilon}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}}\) (\({\varvec{H}}=\boldsymbol{\Delta }{{\varvec{\varepsilon}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\boldsymbol{\Delta }{{\varvec{\varepsilon}}}_{{\varvec{i}}}\)) estimated by the one-step difference GMM, the estimator is called the two-step difference GMM. These estimators are downward biased, if they indicate i) strong autoregression processes and ii) the variances of fixed effects are larger than those of error terms. Blundell and Bond (1998) propose to perform a system GMM estimation by adding the following additional moment conditions: \(E\left[{\varepsilon }_{it}\Delta {Y}_{it-1}\right]=0 (i=1,\cdots ,N; t=\mathrm{3,4},\cdots ,T)\) to those used in the difference GMM. As in the difference GMMs, there is a one-step system GMM and a two-step system GMM. A serious problem with these estimators is that the moment conditions generate too many instruments and create the identification problem. To overcome this problem, we sometimes use the collapsed instruments code included in STATA.

It is important to note that to perform a DPE, all of the estimation methods described above must be tried. Then, diagnostic tests are used to determine statistically robust estimates. There are five diagnostic tests: the Arellano–Bond test for AR(1), the Arellano–Bond test for AR(2), the Hansen J test, the Difference-in-Hansen test, and the Wald test. The estimate that passes all five tests is then selected as our estimate.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takahashi, H. Re-estimation of the savings retention coefficient in OECD countries: a new measure of home country bias. Economic Structures 12, 18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-023-00310-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-023-00310-1

Keywords

- Savings retention coefficient

- Financial globalization

- Equity home country bias measure (EHB)

- Home country bias measure (HBM)

- Tobin’s q-theory

- Dynamic panel estimation (DPE)