Abstract

Red pepper is enriched in antioxidant components, such as carotenoids, phenolic compounds, and vitamins. In this study, we investigated the natural variability in the content of carotenoids and phenolic acids in 11 red pepper cultivars grown in two locations in South Korea during 2016, 2017, and 2018. Seven carotenoids and six phenolic acids, including soluble and insoluble forms, were detected in the red fruit pericarps. The major carotenoids were β-carotene (40%) and capsanthin (20%). The content of insoluble phenolic acids was higher than that of soluble phenolic acids because of the large amount of insoluble p-coumaric acid. The statistical analysis of combined data showed significant differences among varieties, locations, and years for most of the measured components. The results from variance component analysis indicated that the effects of location, year and the interaction of location and year mainly accounted for the variation in carotenoids, whereas variations in phenolic acid content were attributed to year and variety. In addition, the results of principal component analysis and orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant showed that carotenoids were well discriminated by location and year, whereas phenolic acids were distinctively separated only by year. The data from this study could explain the natural variation in the content of carotenoids and phenolic acids in red pepper fruits by genotype and environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pepper (genus Capsicum), which belongs to the family Solanaceae, is one of the most economically and agriculturally important vegetable crops in the world. Pepper is consumed raw or as a food product for its unique flavors (either spicy or sweet) and coloring in most global cuisines. There are 39 species in capsicum, including five domesticated species, Capsicum annuum (e.g., bell peppers, sweet peppers, and hot peppers), C. baccatum (e.g., South American ají peppers), C. chinense (e.g., Habanero peppers), C. frutescens (e.g., South American rocoto peppers), and C. pubescens (e.g., Tabasco peppers), with more than 20 varieties [1]. Their wide diversity in morphological, agronomical, and quality-related traits allows the development of new varieties for use in the industry and market [2]. To improve genetic metabolic traits, especially health-related compounds, comparative analyses of metabolite compositions have been conducted in a diverse collection of peppers [3,4,5]. In addition, the genome sequencing of C. annuum L. has enabled the understanding of the association between genomic studies and important traits of C. annuum L. [6].

Pepper is a nutritionally excellent source of essential vitamins, minerals, and nutrients that offer health benefits to consumers. Bioactive compounds that are enriched in peppers, such as carotenoids, capsaicinoids, phenolics, ascorbic acid, and tocopherols, contribute to antioxidant activity and consequently prevent inflammatory diseases [2, 7,8,9]. Recently, sweet pepper extracts were shown to exhibit inhibitory effects on key enzymes relevant to Alzheimer’s disease [10]. Carotenoids are the major phytochemicals found in the pepper varieties. Biosynthetic pathways and sequestration of carotenoids in Capsicum species have been well identified [11, 12]. The red pigments capsanthin and capsorubin are produced at the end of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway, catalyzed by capsanthin-capsorubin synthase from antheraxanthin and violaxanthin, respectively [13, 14]. The extended linear conjugated double bonds of carotenoids scavenge free radicals. The excellent antioxidant activities of capsanthin and capsorubin result from their conjugated keto extended polyene chains [15]. In addition, pepper fruit is one of the primary dietary sources of provitamin A carotenoids, including β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and α-carotene. Recently, Hassan et al. [14] summarized the antioxidant activities and health-promoting functional attributes of pepper carotenoids. Carotenoids are responsible for the yellow and red colors of pepper varieties. The yellow colors are attributable to lutein and violaxanthin, whereas the red ones are attributable to the ketocarotenoids, capsanthin and capsorubin, and antheraxanthin [14, 16].

In addition to carotenoids, peppers are rich in phenolic compounds, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, which contribute to flavor, color, and health-promoting antioxidant properties [7, 17,18,19]. In sweet peppers, phenolic compounds are predominantly found in the pericarp and placenta [18, 19]. Phenolic acids contain a phenolic ring and an organic carboxylic acid. The antioxidant property of phenolic acids is due to the phenolic ring, which stabilizes and delocalizes unpaired electrons. There are C6-C1 skeleton of hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives (gallic, protocatechuic, p-hydrobenzoic, vanillic, and syringic acids) and C6-C3 skeleton of hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (p-coumaric, ferulic, caffeic, sinapic, chlorogenic, and cinnamic acids) [20]. The major phenolics found in pepper fruits have been identified as derivatives of quercetin, ferulic acid, sinapic acid, apigenin, and luteolin, and are present in free and/or bound forms [7, 21].

Pepper cultivars show variation in the levels of carotenoids and phenolic compounds due to genetic variability [3, 7, 15, 22]. Even within the same variety, the composition and amount of carotenoids and phenolic compounds may differ significantly depending on developmental stages, growing regions, and agricultural practices [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. For example, it was reported that the lower content of β-carotene in the green mature pepper was slightly increased during the breaker stage and increased significantly during the red ripe stage [24]. Green peppers generally possess higher content of phenolic compounds than red ones in sweet peppers [28]. The interaction between cultivar and growing environment significantly affected the accumulation of carotenoids and phenolic compounds [25]. For example, cultivars grown under white shade net favored the accumulation of phenolic compounds, whereas those grown under controlled temperature plastic tunnels improved the accumulation of carotenoid components [21]. Comparative metabolite studies in pepper fruits and crop grains by multisite cultivation have suggested that selection of appropriate cultivars and growing regions enables increased metabolites in plants [27, 31,32,33]. To improve the biological effects of bioactive compounds in sweet peppers, their biosynthesis can be manipulated by environmental conditions and genotypes.

In our previous study, the contents of proximate, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids, capsaicinoids, and free sugars were determined in 12 Korean commercial varieties (C. annuum L.) of pepper, grown in two places in South Korea, Imsil (IS) and Yeongyang (YY), over two consecutive years (2016 and 2017) [34]. The levels of these compositions varied considerably according to genotype, growing environment, and their interactions. Carotenoids and phenolic compounds add high commercial value to pepper by contributing to its taste, color, flavor, and antioxidant properties. These compounds act synergistically as efficient free radical scavengers [25].

Here, we investigated the profiles of carotenoids and soluble and insoluble phenolic acids in the same pepper varieties examined in a previous study, except for one (that is a total of 11 varieties), and in the additional pepper varieties produced in 2018. The effects of genotype, environment, and genotype-environment interactions on the contents of carotenoids and phenolic acids in pepper fruit were determined using statistical methods.

Materials and methods

Plant materials, fruit collection, and sample preparation

Eleven pepper cultivars (AJB, BST, GCH, HBC, JSN, MCB, MM, PJDG, PKST, PMBI, and PSUL) were selected from among the recommended cultivars by local farmers in South Korea. Commercial varieties of pepper were grown in two places in South Korea, IS and YY, for three years (2016, 2017, and 2018). IS and YY are representative areas for pepper production localized in the western and eastern regions of South Korea, respectively. At each location, plants were planted in May, and pepper fruits were harvested in October. All cultivars were planted in two blocks with a strip-plot design. Pepper fruits were collected randomly from each block, pooled together, and then oven-dried at 55 °C for 30 h. After the stalks, seeds, and placenta were removed from the whole fruit, pericarps were ground using a laboratory mill (Retsch planetary mono mill, PM100) and stored at -70 °C until compositional analysis was performed. All experiments were conducted in triplicate by collecting three samples from the pooled powered samples.

Compositional analysis of carotenoids

The carotenoid content of pepper fruits was determined following the method described by Park et al. [35]. Carotenoids were extracted from powdered pepper pericarps (0.03 g) by adding 3 mL of ethanol containing 0.1% ascorbic acid (w/v) and 20 µL of β-Apo-8′-carotenal (25 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as an internal standard, vortexing for 20 s, and placing in a water bath at 85 °C for 5 min. The extract was saponified with potassium hydroxide (80% w/v, 120 µL) in a water bath at 85 °C for 10 min. The tubes were immediately cooled in an ice bucket for 5 min, and cold distilled water (1.5 mL) and hexane (1.5 mL) were added. The contents were vortexed, and the mixture was centrifuged at 1200 × g, 4 °C for 5 min. The upper hexane layer was then collected and 1.5 mL of hexane was added to the remaining solution, and the process was repeated. The pooled hexane layers were concentrated under nitrogen gas and then in a rotary evaporator (MCFD8518, ilShin, Gyeonggi-do, Korea). Finally, the obtained samples were dissolved in 50:50 (v/v) dichloromethane/methanol (125 µL) and injected into an HPLC system (Agilent 1100, Massy, France) equipped with a C30 YMC column (250 × 4.6 mm, 3 µm; YMC Co., Kyoto, Japan) and a photodiode array detector. Measurements were taken at 450 nm and the quantification data were obtained using calibration curves that were drawn by plotting four concentrations of the carotenoid, ranging from 0.5 µg/mL to 50 µg/mL, according to the peak area ratios with the internal standard. Seven carotenoid standards (antheraxanthin, capsanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, α-carotene, and β-carotene) were purchased from CaroteNature (Lupsingen, Switzerland).

Compositional analysis of individual phenolic acids

The extraction procedure of methanol-soluble (free and esterified forms) and -insoluble (bound form) phenolics was performed according to Park et al. [36]. The powdered samples (0.02 g) were extracted twice by water-based sonication for 3 min at 25 °C and incubated at 30 °C for 10 min with 1 mL of 85% methanol containing 2 g/L butylated hydroxyanisole (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After centrifugation at 15,300 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the combined extracts and residues were analyzed to determine the quantities of soluble and insoluble bound phenolic acids, respectively. Fifty microliters of 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid (100 µg/mL; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) was added as an internal standard, and the mixture was hydrolyzed with 1 mL 5 N NaOH at 30 °C under nitrogen gas for 4 h. Each hydrolyzed sample was adjusted to a pH of 1.2–2.0 with 6 N HCl. With unhydrolyzed soluble fractions (free forms), all extracts were extracted with ethyl acetate and evaporated in a centrifugal concentrator (CVE-2000, Eyela, Tokyo, Japan).

For derivatization of the dried extracts, N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide containing 1% tert-butyldimethylchlorosilane and pyridine were used. Each derivatized sample (1 µL) was injected into a 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent, Atlanta, GA, USA) using a 7683 B autosampler (Agilent) with a split ratio of 10, and separated on a 30 m × 0.25-mm i.d. fused silica capillary column coated with 0.25-µm CP-SIL 8 CB low bleed (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) and then introduced into a Pegasus HT time-of-flight mass spectrometer (LECO, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The injector temperature, flow rate of the transfer gas, temperature program, temperature of the transfer line, and ion source were set according to the Park et al. method [36]. The detected mass range was m/z 85–700, and the detector voltage was set to 1800 V. Six standard phenolics (ferulic, p-coumaric, p-hydroxybenzoic, sinapic, syringic, and vanillic acids) and 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid (internal standard) were used for quantification. Chemical, vanillic, syringic, and sinapic acids were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ferulic and p-hydroxybenzoic acids were acquired from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). p-Coumaric acid was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA). Calibration curves were drawn using phenolic acid standards ranged from 0.01 to 10.0 µg.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). To identify differences among capsicum varieties between two locations and among the three locations, combined data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis. The mean discrimination was performed by applying Bonferroni-corrected t-tests, and statistically significant differences were determined at a probability level of p < 0.05. To determine the main effects of variety, location, year, and their interactions for the contents of carotenoids and phenolic acids, data were subjected to ANOVA analysis using the following linear model:

In this model, Yijk is the observed response for variety i at location j of year k, and U is the overall mean, Vi is the entry effect, Lj is the location effect, Yk is the year effect, VLij is the variety-by-location interaction effect, VYik is the variety-by-year interaction effect, LYjk is the location-by-year effect, VLYijk is the variety-by-location-by-year interaction effect, and eijk is the residual error. All variables were regarded as fixed effects. For each trait, mean square values were used to estimate the magnitude of the observed effect, whereas the total sum of squares in percentage (TSS%) was calculated by dividing the TSS of the variable by the total TSS.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal projections to latent structure discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) for carotenoids and total phenolic acids were performed using SIMCA version 13 (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) to evaluate the differences among groups of multivariate data. The PCA and OPLS-DA outputs consisted of score plots to visualize the contrast between different samples and loading plots to explain the cluster separation.

Results and discussion

Carotenoid composition

In previous studies, the main carotenoids of peppers are capsanthin, capsorubin, β-carotene, zeaxanthin, violaxanthin, lutein, and antheraxanthin, which can vary in composition and content based on genetics and fruit maturation stage [3, 19, 28,29,30] Table 1 shows the combined carotenoid data in red pepper pericarps obtained from IS and YY during 2016, 2017, and 2018. Seven carotenoid components, namely antheraxanthin (29.9 ~ 37.4 µg/g dw), capsanthin (89.0 ~ 110.1 µg/g dw), α-carotene (4.7 ~ 6.6 µg/g dw), β-carotene (143.2 ~ 254.7 µg/g dw), β-cryptoxanthin (32.4 ~ 56.6 µg/g dw), lutein (6.6 ~ 12.3 µg/g dw), and zeaxanthin (35.0 ~ 100.2 µg/g dw), were detected in red fruit pericarps. The total carotenoid content ranged from 392.7 µg/g dw for PKST to 543.3 µg/g dw for MCB, indicating statistically significant variations between cultivars. Pepper fruits showed different colors according to the composition of carotenoids [3, 9]. The contents and compositions of carotenoids were different in four colored sweet peppers (green, red, orange, and yellow) [9]. In this previous study, only capsanthin (16.13 ~ 178.20 µg/g dw), trans-β-carotene (8.32 ~ 41.72 µg/g dw), and cis-β-carotene (6.81 ~ 34.28 µg/g dw) were found in all the four sweet peppers. However, lutein (45.16 ~ 115.16 µg/g dw), zeaxanthin (70.71 ~ 191.76 µg/g dw), β-cryptoxanthin (7.55 ~ 40.49 µg/g dw), and α-carotene were detected in certain colored sweet peppers. For instance, lutein and α-carotene were not detected in only red sweet peppers, whereas all carotenoids were detected in orange sweet pepper. While the contents of capsaicin were higher than those of zeaxanthin in Thumphairo et al. [9], in our study, the major carotenoids were β-carotene (~ 41.5%) and capsanthin (~ 20%), followed by zeaxanthin (~ 11%), β-cryptoxanthin (~ 10.7%) and antheraxanthin (~ 5.9%) obtained from IS across three years. The levels of lutein and α-carotene were low (~ 2.2 and ~ 1.3%, respectively).

Variations in carotenoid content were observed among pepper varieties in previous studies [10. 17]. Statistical significance was observed for the variation in the levels of β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and lutein among the 11 varieties, across the two locations for three years (Table 1). The β-carotene content in these varieties ranged from 143.2 to 254.7 µg/g dw. MM showed the highest β-carotene content, whereas HBC had the lowest content. The location effect across 11 pepper varieties was significant for zeaxanthin, β-cryptoxanthin, α-carotene, β-carotene, and capsanthin (Table 1). Overall, the levels of carotenoid compounds were higher in peppers grown in IS than in YY. The contents of all compounds varied based on the cultivation year (Table 1). Overall, the contents of all compounds were the lowest in 2016 compared with those in 2017 and 2018. Individual varieties exhibited a broad range of carotenoid compositions according to cultivation location and year (Additional file 1: Fig. S2), indicating that the carotenoid content in pepper fruits is influenced by environmental factors. For example, MM showed the highest content of β-carotene at IS in 2018 (255.4 µg/g dw) and the lowest β-carotene content at IS in 2016 (199.2 µg/g dw) (Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

Phenolic acids

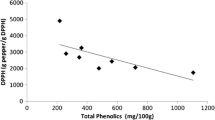

Phenolic acid levels in the methanol-soluble (free) and-insoluble (bound) phenolic fractions of peppers were determined using gas chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry. We presented data as total phenolic acids (that is sum of soluble and insoluble forms). In capsicum fruits, p-coumaric, caffeic, sinapic, and ferulic acids are the major phenolic acid derivatives [7]. Limited studies are available on the levels of phenolic acids in pepper fruits. Zhuang et al. [10] identified seven phenolic acids in fresh pepper fruits of nine cultivars, including gallic (nd ~ 16.12 µg/g fw; nd for non-detected, fw for fresh weight), 3,4-dihydrobenzoic (0.40 ~ 31.39 µg/g fw), vanillic (0.05 ~ 3.26 µg/g fw), benzoic (0.15 ~ 176.76 µg/g fw), and salicylic acids (nd ~ 70.61 µg/g fw), catechin (4.14 ~ 8.13 µg/g fw), and luteolin (0.53 ~ 0.84 µg/g fw). In our study, the contents (in µg/g dw) of the six total phenolic acids (p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, syringic, p-coumaric, ferulic, and sinapic acids) quantified in 11 pepper cultivars across two locations for three years are presented in Table 2 and Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2 for soluble phenolic acids and insoluble phenolic acids, respectively. In addition, soluble, insoluble, and total phenolic acids of each individual variety by location and year are shown in Additional file 1: Figs. S3, S4, and S5, respectively.

In our study, six phenolic acids were detected in both the soluble and insoluble fractions. p-Coumaric acid was found mainly in the insoluble form, whereas others were present more abundantly in the soluble form (Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2). The contents of p-Coumaric acid ranged from 16.02 µg/g dw to 22.47 µg/g dw in the soluble fractions, whereas they were from 288.1 µg/g dw to 349.7 µg/g dw in the insoluble fractions (Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2). Lekala et al. [24] showed that 11 red sweet pepper cultivars grown under shade nets and controlled-temperature plastic tunnel environments exhibited higher levels of phenolic acids in the free extract than in the bound extracts. Whereas caffeic acid was found both in the free extracts (26.6 ~ 80.1 µg/g dw) and in the bound extracts (nd ~ 2.1 µg/g dw), p-hydroxybenzoic (nd ~ 28.9 µg/g dw), vanillic (nd ~ 4.1 µg/g dw), p-coumaric (2.0 ~ 13.7 µg/g dw), ferulic (6.0 ~ 13.4 µg/g dw), and sinapic acids (nd ~ 35.2 µg/g dw) were found only in the bound extract [24], which is inconsistent with our study. In contrast, Alu´datt et al. [22] reported that the contents and profiles of free and bound phenolic contents in five various peppers, with different extract conditions. In previous study [22], phenolic acids were present more abundantly in the free extracts than in the bound extract for five peppers. The contents of individual free and bound phenolics were dependent on pepper-cultivar and on the extraction conditions. For example, caffeic acid was found in green hot and green sweet peppers but not in yellow sweet, red hot, and red sweet peppers. In addition, for red sweet pepper, ferulic acids were 32.4% and 66.4% in bound phenolic-base and-acid extract, respectively [22]. In our study, the sum of individual phenolic acids was higher in the insoluble fraction than in the soluble fraction because of the higher levels of p-coumaric acid in the insoluble fraction (Additional file 1: Tables S1, S2). Some of the discrepancies may have resulted from differences in plant materials, extraction methods, and analytical methods.

Previous studies have shown that the composition and content of phenolic acids differ considerably based on chili pepper cultivars, fruit maturation stage, and agricultural practices [7, 10, 23]. In total phenolic acids, the less abundant phenolic was syringic acid (PSUL variety with a mean content of 8.2 µg/g) and the most abundant one was p-coumaric acid (PMBI variety with a mean content of 367.2 µg/g), followed by ferulic (GCH variety with a mean content of 159.3 µg/g) and sinapic acids (HBC variety with a mean content of 151.6 µg/g) (Table 2). The contents of vanillic (41.3 ~ 64.0 µg/g dw), syringic (8.2 ~ 10.2 µg/g dw), ferulic (96.0 ~ 136.4 µg/g dw), and sinapic acids (78.6 ~ 151.6 µg/g dw) were significantly different among the 11 varieties (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA), whereas no difference was found for p-coumaric acid (312.8 ~ 367.2 µg/g dw) and p-hydroxybenzoic acid (28.5 ~ 36.9 µg/g dw) contents (Table 2). The levels of p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, syringic, and p-coumaric acids were significantly different in peppers grown at two locations across varieties and cultivation years (Table 2). p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, and p-coumaric acids were higher in peppers cultivated in IS than in those cultivated in YY. In addition, all phenolic acids varied according to cultivation year (Table 2). Overall, peppers from 2017 across varieties and locations had higher phenolic acid contents compared to other years. For example, p-coumaric acid was specifically higher at both locations in 2017 (Additional file 1: Fig. S3). Each pepper variety exhibited a broad range of individual phenolic acid compositions (soluble, insoluble, and total) according to cultivation location and year (Additional file 1: Figs. S3–S5), indicating the contribution of the environment to phenolic acids.

Variance components and genotype-environment effect

ANOVA using the linear model was applied to data across the two locations for three years to determine the extent of variables (genotype, location, year, and respective interactions) influencing carotenoids and total phenolic acids (Table 3). For all the components measured, the genotype effect (variety) was significant, with the exception of antheraxanthin and p-coumaric acid. The location effect was significant for all components, with the exception of capsanthin. The year effect was significant for all components. With regard to carotenoids, the contents of zeaxanthin and β-cryptoxanthin were strongly affected by the location effect, accounting for 41% and 33.4%, respectively, expressed by TSS%. The β-carotene content was influenced by variety (27.8%), followed by year (21.1%), whereas α-carotene and capsanthin were most influenced by year, with 40.6% and 78.5% TSS% values, respectively. This observation is in agreement with Kumar and Goel [28], who reported that the location of production (field vs. glasshouse), stage of development, cultivar, and their interactions are major variables that determine carotenoid levels in several pungent and non-pungent peppers.

Total phenolic acids, including p-coumaric acid (83.4%), ferulic acid (64.1%), p-hydroxybenzoic acid (50.2%), and vanillic acid (34.1%), were predominantly influenced by the year, with less variation due to the growing locations. Syringic acid and sinapic acid were most influenced by the variety, with 45.8%, followed by the year effects (30.3% and 39.6%, respectively). Although to a lesser degree, the interactions of variety and environmental factors (V × L, V × Y, and V × L × Y), and the interaction of environmental factors (L × Y) were significant for most of the carotenoids and total phenolic acids. Among them, the L × Y effect was the major contributor in the level of carotenoids.

PCA and OPLS-DA of carotenoids and phenolic acids

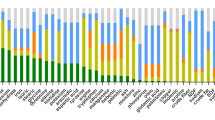

Chemometric methods, such as PCA and OPLS-DA, are useful for the classification of compositional datasets from different environments or genotypes [37,38,39]. PCA and OPLS-DA were employed to investigate the degree to which compositions are separated by cultivar, location, and cultivation year (Fig. 1). In addition, the loading score plots of PCA and OPLS-DA were used to identify the components responsible for data variation (Additional file 1: Fig. S6). The PCA results for carotenoids and phenolic acids by varieties showed no apparent separation among the 11 pepper varieties (Fig. 1a, d). These results demonstrated that these components were not significantly differentiated by genotype.

Score plots of the principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal projections to latent structure discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) obtained from compositional data of 11 red pepper varieties. Data of carotenoids and total phenolic acids were subjected to PCA by variety (a, d), and to OPLS-DA by location (b, e) and to OPLS-DA by cultivation year (c, f). PC1 principal component 1, PC2 principal component 2; OPLS 1 in (b, c, e, f), predictive component 1; OPLS 2 in (b, e), X side orthogonal component 1; OPLS 2 in (c, f), predictive component 2

OPLS-DA is a supervised partial least squares regression method in which can divide the systematic variation in the X variables into two parts: (1) that models the correlation between X and Y (prediction), and (2) that models the orthogonal components. It can be used to identify the variables responsible for class discrimination [40]. In this study, OPLS-DA of data indicated better separation than PCA for location and cultivation year. Carotenoids were well clustered by location and cultivation year (Fig. 1b, 1c). The R2 and Q2 values indicate the explained variance of the total variance and prediction goodness parameter, respectively, and were calculated minimum zero to maximum one. The R2 value closer to 1 indicates a good value, and if Q2 > 0.5, the model is considered to have good predictive capacity [41]. The model showed one predictive and 5 orthogonal components, with R2 = 0.697 and Q2 = 0.643 in carotenoids by location. OPLS 1 (predictive component 1) separated carotenoids of the peppers grown in IS and YY (Fig. 1b), which is consistent with the higher levels of carotenoids in peppers from IS than in those grown in YY (Table 1). In addition, the model showed three predictive and two X side orthogonal components, with R2 = 0.806 and Q2 = 0.774 in carotenoids by cultivation year. OPLS 1 (predictive component 1) separated carotenoids of the pepper grown in 2018 from those grown in 2016 and 2017, whereas OPLS 2 (predictive component 2) separated carotenoids of the pepper grown in 2017 from 2016 and 2018 (Fig. 1c). With respect to phenolic acids, the model showed one predictive and five X side orthogonal components, with R2 = 0.353 and Q2 = 0.262 by location, but IS and YY were not well segregated (Fig. 1e). The model showed the three predictive components and three X side orthogonal components, with R2 = 0.689 and Q2 = 0.628 in phenolic acids by cultivation year. The phenolic acid contents of the peppers grown in the three years were distinctively separated across OPLS 1 (prediction component 1, 53.6%) and OPLS 2 (prediction component 2, 9.49%) (Fig. 1f). This is consistent with the higher phenolic acids overall in 2017 compared with those from the cultivation years 2016 and 2018 (Table 1). The variation in OPLS 1 of phenolic acids by cultivation year was attributable to p-coumaric and ferulic acids, whereas that in OPLS 2 was due to syringic acid (Additional file 1: Fig. S6f). These results indicate that variations in carotenoids and phenolic acids are greatly influenced by the location and cultivation year.

The present study demonstrated that genotype (variety), environment (location and year), and genotype-environment interactions had significant effects on the levels of carotenoids and phenolic acids in 11 pepper fruit pericarps produced at two locations over three years. Although most components measured showed significant differences among the 11 pepper varieties grown at both locations per year, the genotypic effect was a relatively minor source of variation in the 11 red pepper varieties across the six environments. Regarding the carotenoid levels, overall, peppers from IS exhibited higher levels of carotenoids than those from YY, and it was the lowest in 2016 compared with those in 2017 and 2018. Variance component analysis demonstrated major roles of the location, the year, and the interaction of location and year effects in the variation. Total phenolic acids, overall, were higher in the peppers from IS than from YY, and it was the highest in 2017 compared to other years. The results from variance component analysis showed that the year and genotype mainly accounted for the variation of total phenolic acids. Finally, the chemometric evaluation verified discrimination by location and year for carotenoids, and by location for phenolic acids. Taken together, the accumulation of carotenoids and phenolic acids in the pericarps of pepper fruits can be determined by genotype, but they can be strongly influenced by the growing environment. Thus, the selection of growing regions needs to be considered to optimize pepper fruit traits as well as pepper varieties.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Bosland PW, Votava EJ (2012) Peppers: vegetable and spice capsicums, 2nd edn. CABI, London

Baenas N, Belović M, Ilic N, Moreno DA, García-Viguera C (2019) Industrial use of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) derived products: technological benefits and biological advantages. Food Chem 274:873–885

Wahyuni Y, Ballester A-R, Sudarmonowati E, Bino RJ, Bovy AG (2011) Metabolite biodiversity in pepper (Capsicum) fruits of thirty-two diverse accessions: variation in health-related compounds and implications for breeding. Phytochemistry 72:1358–1370

Kantar MB, Anderson JE, Lucht SA, Mercer K, Bernau V, Case KA, Le NC, Frederiksen MK, Dekeyser HC, Wong Z-Z et al (2016) Vitamin variation in Capsicum spp. provides opportunities to improve nutritional value of human diets. PLoS ONE 7:1–12

Sarpras M, Gaur R, Sharma V, Chhapekar SS, Das J, Kumar A, Yadava SK, Nitin M, Brahma V, Abraham SK et al (2016) Comparative analysis of fruit metabolites and pungency candidate genes expression between Bhut Jolokia and other Capsicum species. PLoS ONE 11:e0167791

Kim S, Park M, Yeom S-I, Kim Y-M, Lee JM, Lee HA, Seo E, Choi J, Cheong K, Kim KT et al (2014) Genome sequence of the hot pepper provides insights into the evolution of pungency in Capsicum species. Nat Genet 46:270–279

Materska M, Perucka I (2005) Antioxidant activity of the main phenolic compounds isolated from hot pepper fruit (Capsicum annuum L.). J Agric Food Chem 53:1750–1756

Marín A, Ferreres F, Tomás-Barberán FA, Gil MI (2004) Characterization and quantitation of antioxidant constituents of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). J Agric Food Chem 52:3861–3869

Thuphairo K, Sornchan P, Suttisansanee U (2019) Bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and inhibition of key enzymes relevant to alzheimer’s disease from sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum) extracts. Prev Nutr Food Sci 24:327–337

Zhuang Y, Chen L, Sun L, Cao J (2012) Bioactive characteristics and antioxidant activities of nine peppers. J Funct Foods 4:331–338

Gómez-García MR, Ochoa-Alejo N (2013) Biochemistry and molecular biology of carotenoid biosynthesis in chili peppers (Capsicum spp.). Int J Mol Sci 14:19025–19053

Berry HM, Rickett DV, Baxter CJ, Enfissi EMA, Fraser PD (2019) Carotenoid biosynthesis and sequestration in red chilli pepper fruit and its impact on colour intensity traits. J Exp Bot 70:2637–2650

Muhammad Shah SN, Tian S-L, Gong Z-H, Mohamed Hamid A (2014) Studies on metabolism of capsanthin and its regulation under different conditions in pepper fruits (Capsicum spp.). Ann Res Rev Biol 4:1106–1120

Hassan NM, Yusof NA, Yahaya AF, Rozali NNM, Othman R (2019) Carotenoids of Capsicum fruits: pigment profile and health-promoting functional attributes. Antioxidants 8:469

Pérez-Gálvez A, Minguez-Mosquera MI (2001) Structure-reactivity relationship in the oxidation of carotenoid pigments of the pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). J Agric Food Chem 49:4864–4869

Hornero-Méndez D, Minguez-Mosquera MI (2000) Rapid spectrophotometric-determination of red and yellow isochromic carotenoid fractions in paprika and red pepper oleoresins. J Agric Food Chem 49:3584–3588

Guzman I, Vargas K, Chacon F, McKenzie C, Bosland PW (2021) Health-promoting carotenoids and phenolics in 31 Capsicum Accessions. HortScience 56:36–41

Sricharoen P, Lamaiphan N, Patthawaro P, Limchoowong N, Techawongstien S, Chanthai S (2017) Phytochemicals in Capsicum oleoresin from different varieties of hot chilli peppers with their antidiabetic and antioxidant activities due to some phenolic compounds. Ultrason Sonochem 38:629–639

Martin A, Ferreres F, Tomas-Barberan FA, Gil MI (2004) Characterization and quantitation of antioxidant constituents of sweet pepper (Capsium annuum L.). J Agric Food Chem 52:3861–3869

Blanco-Ríos AK, Medina-Juárez LA, González-Aguilar GA, Gámez-Meza N (2013) Antioxidant activity of the phenolic and oily fractions of different sweet bell peppers. J Mex Chem Soc 57:137–143

Kumar N, Goel N (2019) Phenolic acids: natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol Rep 24:e00370

Alu´datt MH, Rababah T, Alhamad MN, Gammoh S, Ereifej K, Al-Karaki G, Tranchant CC, Al-Duais M, Ghozlan KA, (2019) Contents, profiles and bioactive properties of free and bound penolics extracted from selected fruits of the Oleaceae and Solanaceae families. LWT Food Sci Technol 109:367–377

Guilherme R, Aires A, Rodrigues N, Peres AM, Pereira JA (2020) Phenolics and antioxidant activity of green and red sweet peppers from organic and conventional agriculture: a comparative study. Agriculture 10:652

Lekala CS, Madani KSH, Phan ADT, Maboko MM, Fotouo H, Soundy P, Sultanbawa Y, Sivakumar D (2019) Cultivar-specific responses in red sweet peppers grown under shade nets and controlled-temperature plastic tunnel environment on antioxidant constituents at harvest. Food Chem 275:85–94

Conforti F, Statti GA, Menichini F (2007) Chemical and biological variability of hot pepper fruits (Capsium annuum var. acuminatum L.) in relation to maturity stage. Food Chem 102:1096–1104

Ribes-Moya AM, Adalid AM, Raigón MD, Hellín P, Fita A, Rodríguez-Burruezo A (2019) Variation in flavonoids in a collection of peppers (Capsicum sp.) under organic and conventional cultivation: effect of the genotype, ripening stage, and growing system. J Sci Food Agric 100:2208–2223

Bhandari SR, Jung B-D, Baek H-Y, Lee Y-S (2013) Ripening-dependent changes in phytonutrients and antioxidant activity of red pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruits cultivated under open-field conditions. HortScience 48:1275–1282

Russo VM, Howard LR (2002) Carotenoids in pungent and non-pungent peppers at various developmental stages grown in the field and glasshouse. J Sci Food Agric 82:615–624

Tripodi P, Cardi T, Bianchi G, Migliori CA, Schiavi M, Rotino GL, Lo Scalzo R (2018) Genetic and environmental factors underlying variation in yield performance and bioactive compound content of hot pepper varieties (Capsicum annuum) cultivated in two contrasting Italian locations. Eur Food Res Technol 244:1555–1567

Tripodi P, Lo Scalzo R, Ficcadenti N (2020) Dissection of heterotic, genotypic and environmental factors influencing the variation of yield components and health-related compounds in chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum). Euphytica 216:112

Lo Scalzo R, Campanelli G, Paolo D, Fibiani M, Bianchi G (2020) Influence of organic cultivation and sampling year on quality indexes of sweet pepper during 3 years of production. Eur Food Res Technol 246:1325–1339

Beleggla R, Plantani C, Nigro F, Vita P, Cattvelli L (2013) Effect of genotype, environment and genotype-by environment interaction on metabolite profiling in durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) grain. J Cereal Sci 57:183–192

Chen M, Rao RSP, Zhang Y, Zhong C, Thelen JJ (2016) Metabolite variation in hybrid corn grain from a large-scale multisite study. Crop J 4:177–187

Kim E-H, Lee S-Y, Baek D-Y, Park S-Y, Lee S-G, Ryu T-H, Lee S-K, Kang HJ, Kwon O-H, Kil M et al (2019) A comparison of the nutrient composition and statistical profile in red pepper fruits (Capsicum annuum L.) based on genetic and environmental factors. Appl Biol Chem 62:48

Park S-Y, Lim S-H, Ha S-H, Yeo Y, Park WT, Kwon DY, Park SU, Kim JK (2013) Metabolite profiling approach reveals the interface of primary and secondary metabolism in colored cauliflowers (Brassica oleracea L. ssp. botrytis). J Agric Food Chem 61:6999–7007

Park S-Y, Kim JK, Lee SY, Oh S-D, Lee SM, Jang J-S, Yang C-I, Won Y-J, Yeo Y (2014) Comparative analysis of phenolic acid profiles of rice grown under different regions using multivariate analysis. Plant Omics 7:430–437

Baker JM, Hawkins ND, Ward JL, Lovegrove A, Napier JA, Shewry PR, Beale MH (2006) A metabolomic study of substantial equivalence of field-grown genetically modified wheat. Plant Biotechnol J 4:381–392

Kokkinofta R, Yiannopoulos S, Stylianou MA, Agapiou A (2020) Use of chemometrics for correlating Carobs nutritional compositional values with geographic origin. Metabolites 10:62

Kim TJ, Park JG, Kim HY, Ha S-H, Lee B, Park SU, Seo WD, Kim JK (2020) Metabolite profiling and chemometric study for the discrimination analyses of geographic origin of Perilla (Perilla frutescens) and Sesame (Sesamum indicum) seeds. Food 9:989

Mehl F, Marti G, Boccard J, Debrus B, Merle P, Delort E, Beroux L, Raymo V, Velazco MI, Sommer H et al (2014) Differentiation of lemon essential oil based on volatile and non-volatile fractions with various analytical techniques: a metabolomic approach. Food Chem 143:325–335

Eriksson L, Johansson E, Kettaneh-Wold N, Trygg J, Wikstrom C, Wold S (eds) (2006) Multi- and megavariate data analysis. Part I: basic principles and application. Umetrics, Sweden

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of "Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Project No. PJ01432202)" Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SWO and SGL: project design and management; KML and SYP: conducting experiments and data analysis; SYL and SGL: assistance in experimental performance; EHK and SYP: manuscript preparation; THR: assistance in manuscript revision; MK and OHK: contributing to pepper materials. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. Soluble phenolic acid contents of 11 red pepper varieties across 2 locations for 3 years by variety. Table S2. Insoluble phenolic acid contents of 11 red pepper varieties across 2 locations for 3 years by variety. Figure S1. Chromatograms of carotenoids (a), and mehtanol-soluble (b) and - insoluble phenolic acids (c) of a red pepper sample (cv. GCH) cultivated at YY fields in 2016. IS 1, β-apo-8′-carotenal; IS 2, 3,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid; 1, antheraxanthin; 2, capsanthin; 3, lutein; 4, zeaxanthin; 5, β-cryptoxanthin; 6, α-carotene; 7, β-carotene; 8, p-hydroxybenzoic acid; 9, vanillic acid; 10, syringic acid; 11, p-coumaric acid; 12, ferulic acid; 13, sinapic acid. Figure S2. Scatter plots of carotenoid composition of 11 pepper varieties grown at Imsil (IS) and Youngyang (YY) in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Each point represents mean of three replicates. Figure S3. Scatter plots of total phenolic acids pepper varieties grown at Imsil (IS) and Youngyang (YY) in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Each point represents mean of three replicates. Figure S4. Scatter plots of soluble phenolic acids pepper varieties grown at Imsil (IS) and Youngyang (YY) in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Each point represents mean of three replicates. Figure S5. Scatter plots of insoluble phenolic acids pepper varieties grown at Imsil (IS) and Youngyang (YY) in 2016, 2017, and 2018. Each point represents mean of three replicates. Figure S6. Loading plots of the principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal projections to latent structure discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) analyses obtained from compositional data of 11 red pepper varieties. Carotenoids and total phenolic acids data were subjected to PCA by variety (a, d), and to OPLS-DA by location (b, e) and to OPLS-DA by cultivation year (c, f). PC1, principal component 1; PC2, principal component 2; OPLS 1 in (b, c, e, f), predictive component 1; OPLS 2 in (b, e), X side orthogonal component 1; OPLS 2 in (c, f), predictive component 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, EH., Lee, K.M., Lee, SY. et al. Influence of genetic and environmental factors on the contents of carotenoids and phenolic acids in red pepper fruits (Capsicum annuum L.). Appl Biol Chem 64, 85 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-021-00657-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-021-00657-8