Abstract

From the biotechnological viewpoint, the enzymatic disintegration of plant lignocellulosic biomass is a promising goal since it would deliver fermentable sugars for the chemical sector. Cellobiose dehydrogenase (CDH) is a vital component of the extracellular lignocellulose-degrading enzyme system of fungi and has a great potential to improve catalyst efficiency for biomass processing. In the present study, a CDH from a newly isolated strain of the agaricomycete Coprinellus aureogranulatus (CauCDH) was successfully purified with a specific activity of 28.9 U mg−1. This pure enzyme (MW = 109 kDa, pI = 5.4) displayed the high oxidative activity towards β-1–4-linked oligosaccharides. Not least, CauCDH was used for the enzymatic degradation of rice straw without chemical pretreatment. As main metabolites, glucose (up to 165.18 ± 3.19 mg g−1), xylose (64.21 ± 1.22 mg g−1), and gluconic acid (5.17 ± 0.13 mg g−1) could be identified during the synergistic conversion of this raw material with the fungal hydrolases (e.g., esterase, cellulase, and xylanase) and further optimization by using an RSM statistical approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As alternative feedstock for biotechnological and industrial applications, lignocellulosic materials like wood and agricultural residues become more and more economically important, not least against the background of intensified utilization of biomass in the sense of the biorefinery concept and the idea of sustainable development. Agricultural crops in Asia are primarily based on wet rice cultivation, annual production of which leaves roughly 600 to 800 million tons of rice straw accounting for 90% of the worldwide amount [1]. Despite the wide potential of rice straw, the challenging goal in converting this lignocellulosic biomass is to produce value-added chemicals at high selectivity and commercial efficiency. Thus, rice straw generally contains complex cell wall polymers such as cellulose (32–39 wt%), hemicellulose (20–36 wt%), and lignin (14 wt%-22 wt%), along with silica and other minor components (10–17wt%) [2], which provide rigidity and mechanical stability and protecting it from microbial and enzymatic attack.

Cellobiose dehydrogenase (CDH; EC 1.1.99.18; cellobiose: [acceptor] 1-oxidoreductase), an extracellular flavocytochrome, is a vital component of the extracellular lignocellulose-degrading enzyme system of both basidiomycetous and ascomycetous fungi [3]. Based on its function to support polysaccharide depolymerization by lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase (LPMO), CDH is classified into the auxiliary activity families (AA3_1) that cover redox enzymes acting in conjunction with carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes; www.cazy.org) [4]. The enzyme catalyzes the oxidation of soluble cellobiose, cellodextrins, mannodextrins, and lactose to their corresponding lactones in the presence of a suitable electron acceptor such as 2,6-dichloro-indophenol (DCIP), cytochrome c (cyt c), or metal ions.

Although biological function of CDHs has not been comprehensively elucidated yet, the previous reports implicate an important role of this oxidative enzyme for bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass into sugars by catalyzing the redox-mediated cleavage of glycosidic bonds in crystalline cellulose and hemicellulose [5, 6]. It is assumed to play a role in reinforcement of manganese peroxidase, lignin peroxidase, laccase and cellulase, reducing aromatic radicals formed during lignin degradation, producing lignocellulose-modifying hydroxyl radicals and catalyzing quinone reduction as detoxification mechanism during fungal plant attack. Due to their bioelectrochemical properties, CDHs have a broad application potential in bioprocesses such as electrobiocatalysis, bioremediation, and in enzyme-based biofuel cells [4, 5, 7, 8]. Numerous CDHs have been isolated and characterized from fungal sources including white-rot fungi, such as Phanerochaete chrysosporium [9], Trametes hirsuta [10], Schizophyllum commune [11], Sporotrichum pulverulentum [12], soft-rot fungi like Chaetomium cellulolyticum [13], Sporotrichum thermophile [14], Humicola insolens [15], and the brown-rot fungus Coniophora puteana [16].

To get more insight into the fungal CDH system, we describe herein the production, purification and characterization of a CDH from a newly isolated fungus Coprinellus aureogranulatus (designated as CauCDH). This agaricomycete was chosen as one of the most efficient CDH producers from nearly fifty fungal strains in our previous screening and selection strategies [17]. Not least, the enzymatic degradation of rice straw without chemical pretreatment was optimized by using the pure CauCDH catalysed synergistically with various hydrolases (e.g., esterase, cellulase, and xylanase) to improve the efficiency of the conversion process.

Materials and methods

Materials

Hydrolase preparation [cellulase and xylanase (Cell/Xyl) activities, 1.0–1.6 U mg−1] from Trichoderma reesei was obtained from AB Enzymes (Darmstadt, Germany). The acetyl (xylan) esterase was purified from the wood-rot fungus Xylaria polymorpha (AE, specific activity of 1.3 U mg−1) as previously described [18].

Rice straw [45.7 wt% cellulose, 22.5 wt% hemicellulose, 19.6 wt% lignin, and 12.3 wt% ash content (dry basis)] was collected from Cu Chi District, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. The paddy straw was thoroughly rinsed and air-dried before ground into pieces of ~ 40 × 40 µm by a planetary ball mill (Fritsch, Oberstein, Germany).

Fungal isolation

The fungus (initially designated as MPG14) growing on deciduous deadwood was collected in the Muong Phang primeval forest (21°27'N, 103°09'E), Dien Bien Province, Northwest Vietnam and isolated using 2% malt-agar plates supplemented with antibiotics (0.005% streptomycin, penicillin, chloramphenicol, benomyl and 0.004% nystatin). The fungal strain used in this study was purified by repeated sub-culturing on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Merck, Germany) and preserved at − 80 °C (25% glycerol); it has been deposited at the Vietnam Type Culture Collection (VTTC, Vietnam) under accession number VTCC 930003.

Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis

The fungal isolate was identified based on the sequence of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the ribosomal gene repeat unit. The genomic DNA was isolated using Plant/Fungi DNA isolation Kit (Norgenbiotek, Canada) and purified using the GeneJET genomic DNA purification kit (Thermo Scientific, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The genomic DNA amplification was achieved by PCR technique with the following primers ITS1: TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG and ITS4: TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC [19]. The 25 μL reaction mixture contained 3 μL of genomic DNA (10–20 ng); 7 μL distilled H2O; 12.5 µL of PCR Master mix kit (2X); 1.25 μL of each primer (10 pmol/μL). The following PCR thermal cycle parameters were used: 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 55 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified products were purified by using Qiaquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, USA). The sequences obtained were analyzed in the ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and compared with GenBank databases (nr) using BLAST tool.

Phylogenetic trees were constructed by using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) [20, 21]. The BI summarized two independent runs of four Markov Chains for 10,000,000 generations. A tree was sampled every 100 generations, and a consensus topology was calculated for 70,000 trees after discarding the first 30,001 trees (burn-in = 3,000,000). Parameter estimates and convergence was checked using Tracer v1.7.1 [22]. Strength of nodal support in the ML tree was analyzed using non-parametric bootstrapping (MLBS) with 1,000 replicates. Pairwise comparisons of uncorrected sequence divergences (p-distance) were calculated in Mega 7.0 [23].

Enzyme activity assay

CDH activity was assayed by recording the decrease in absorbance of 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol (DCIP) at 520 nm in a reaction mixture (200 μL) containing 0.3 mM DCIP, 30 mM lactose and 4 mM NaF in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0). The reaction was initiated by adding an appropriate amount of enzyme extract or purified CDH, and incubation of reaction mixtures occurred at 37 °C for 5 min [24].

Production and purification of cellobiose dehydrogenase

The production of the CDH of C. aureogranulatus (strain MPG14) was performed in the sterile plastic bags, each containing about 500 g rice straw. After three weeks of fungal growth, the proteins were extracted with the distilled water, then the mycelium and straw particles were removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min) and filtration (filter GF6; Whatman, UK). The clear supernatant was repeatedly dialyzed and concentrated in a tangential flow ultrafiltration system at 11 °C (10 kDa cut-off; Sartorius, Germany).

Subsequently, the crude enzyme preparation was purified by three steps of fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) using an ÄKTA Pure system (GE Healthcare, Danderyd, SWE) with a detector operating at 280 nm. The first and final separation steps by ion-exchange chromatography were carried out on DEAE-Sepharose and HiTrap™ Q FF columns, respectively, using sodium acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.0) as the mobile phase. Elution of the target protein was performed with the same buffer and an increasing sodium chloride gradient (0 to 1.5 M for DEAE-Sepharose and 0 to 0.5 M for the HiTrap™ Q FF column respectively). The second purification step was performed by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex™ 75 column and sodium acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.0) containing sodium chloride (100 mM) as the eluent. The fractions with CDH activity were pooled, dialyzed against 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 6.0), and stored at − 80 °C for further use.

Enzyme characterization

Molecular weight (MW) of the purified enzyme was determined by SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE Novex 10% Bis–Tris gel; Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) using an omniPAGE Mini vertical electrophoresis system (Cleaver Scientific, Warwickshire, UK). Analytical isoelectric focusing (IEF) was performed with the same electrophoresis system but using IEF precast gels (Novex IEF gel; Invitrogen) under the conditions described previously [25]. The protein bands were visualized in the gels with a colloidal blue staining kit (Invitrogen). Protein concentrations were determined by using a Roti-Nanoquant protein assay kit (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Spectral studies

Spectra of purified CauCDH were recorded in the range from 250 to 700 nm in both the oxidized and the reduced states using a Spark microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). The spectrum of the reduced enzyme was prepared from its oxidized form by adding 500 mM of cellobiose. The purity of the enzyme from C. aureogranulatus was also assessed using the ratio of the absorbances at 420 and 280 nm of CDH in its oxidized form [6].

Effects of temperature and pH on enzyme activity and stability

The pH profile of purified CauCDH was determined using the assay with DCIP as described above at pH values ranging from pH 4.0 to 8.0. The pH stability of CauCDH was evaluated by incubating the enzyme at 25 °C for different time periods in 100 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.0 as well as in sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 and 8.0.

The temperature optimum was determined by measuring the enzyme activity of CauCDH at different temperatures (30–70 °C) in 100 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.5). The effect of temperature on enzyme stability was studied at 25 °C, 50 °C, and 70 °C in sodium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 5.5). After incubation intervals of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h, aliquots of the samples were taken for measurement of the residual CDH activities.

Kinetic parameters and substrate specificity

The Michaelis–Menten constant (Km), catalytic constant (kcat) of the purified enzyme from C. aureogranulatus MPG14 were determined for various CDH substrates and electron acceptors (Table 2). Kinetics of electron acceptors were measured at 520 nm with 20 mM cellobiose as the electron donor, while DCIP (0.3 mM) was used as the electron acceptor to determine the kinetics of substrate oxidations [28].

Synergistic conversion of rice straw by an enzymatic cocktail containing CauCDH

The rice straw was ground to a fine powder (particle size 40 × 40 µm, determined microscopically). This material (3%, wt/vol) was incubated with CauCDH (specific activity ≥ 28.0 U mg−1) and other selected enzymes (presented in supplementary material, Additional file 1: Table S1) in 100 mM sodium citrate buffer at pH 6.0, at 37 °C under continuous shaking at 50 × g. To follow both synergistic effects and the single effects of each enzyme, enzymatic conversion was performed with each enzyme alone and in combinations on the one hand with all hydrolases [in-house AE from X. polymorpha and commercial AB Enzymes preparation (Cell/Xyl)] and on the other hand, with all tested enzymes. Controls containing heat-denatured enzymes (95 °C for 15 min) were used for comparison. After that, aliquots were taken and the amount of released carbohydrates was quantified by using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (1200 series, Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). The samples were equilibrated at 80 °C in the headspace oven, followed by injection onto a Rezex™ ion-exclusion column [RPM-Monosaccharide Pb+2 (8%), 7.8 mm × 300 mm, Phenomenex®] and monitoring the eluting substances with a refractive-index (RI) detector. For gluconic acid determination, the same HPLC system was used but equipped with a Shim-pack CLC-NH2 column (150 mm × 6 mm, Shimadzu, CA, U.S.A) and a UV detector operating at 210 nm.

Experimental design for optimization by response surface methodology (RSM)

Enzymatic conversion of lignocellulose-rich material (3% rice straw, wt/vol) by pure CauCDH and further hydrolases was optimized to improve the efficiency of the conversion process. The ratio of enzyme to straw substrate (in Units per gram biomass; U g−1) of each enzyme was varied according to the amplitude of the experiment.

The RSM approach, in conjunction with the Box-Behnken design, was employed to estimate the effect of three main fators (enzyme concentrations of Cell/Xyl, AE, and CauCDH) on the product yields [Y] of glucose, xylose, and gluconic acid. Procedure for the construction of the 15-experiment design matrix with the mathematical-statistical treatments and the determination of optimal conditions were carried out using Design-Expert 7.0.0 software (Stat-Ease, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Results of preliminary single factor experiments were used as inputs in an orthogonal design matrix to determine range and central points of variables (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2). To be specific, in this investigation, three parameters were varied individually with other factors being kept in a fix (Additional file 1: Figure S2). Estimating results were tested with ANOVA analysis to confirm model validity (Additional file 1: Table S3). Then, optimal conditions were calculated from the final model and verified by the actual experimental approach (Fig. 5, Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6). The dependent variables (the above product yields) as a function of independent variables were expressed using the following second order polynomial Eq. (1).

where Ŷ is the predicted response; b0 is the intercept coefficient; bj is the linear coefficient; bjj is the square coefficient; buj is the interaction coefficient; Xu and Xj are the coded independent variables, terms of XuXj and Xj2 are the intersection and quadratic terms, respectively.

The three factors [Cell/Xyl, AE, and CauCDH (U g−1)] chosen for this study were designated as A, B, C, respectively. The three variables were coded according to following equation:

where: \({Z}_{j}^{0}= \frac{{Z}_{j}^{max} + {Z}_{j}^{min}}{2} ; {\Delta Z}_{j}= \frac{{Z}_{j}^{max}- {Z}_{j}^{min}}{2}\) \({Z}_{j}\) was the actual value of the variable [Cell/Xyl, AE, and CauCDH (U g−1); Additional file 1: Table S1]; \({Z}_{j}^{0}\) was the actual value of the independent variable at the center point; and \({\Delta Z}_{j}\) was the step change of the variable. A, B, C were prescribed into three levels + 1, 0, − 1 for high, intermediate, and low value, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistically significant differences were realized at p < 0.05 via Student’s t-test. Statistical analysis was performed using the JMP Pro. 13.2 software.

Results

Identification of the isolated fungal strain with high CDH activity

In order to identify the fungal isolate, total DNA was extracted with suitable quality and amplified by PCR with primers (ITS1/ITS4) at an annealing temperature of 55 °C. Both ends of the gene segment were sequenced and a sequence of 453 nucleotides in length was obtained and deposited in GenBank nucleotide database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under the accession number MT427740. Nucleotide sequencing was then compared to the reference sequences in GenBank database. The results revealed 100% identity with the sequences of species Coprinellus aureogranulatus GQ249274. Based on this genetic identification, and additional microscopic characteristics, the strain MPG14 was classified as Coprinellus aureogranulatus (Psathyrellaceae, Agaricales, Agaricomycetes, Basidiomycota; Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Fig. S1), which is a new species for Vietnam (www.gbif.org/species/2534597). Nevertheless, the few existing records indicate that it is a tropical to subtropical species [27].

Purification and physicochemical characterization of CDH from C. aureogranulatus

For purification studies, a sufficient amount of CDH was produced under conditions of solid-state fermentation with rice straw as growth substrate at a larger scale (0.5 kg bags) to obtain a crude extract with a total CDH activity of 1817 U (measured with DCIP). Subsequently, CDH was purified up to 41.9-fold with the yield of 22.7% starting from crude culture filtrate and resulting in a specific activity of 28.9 U mg−1 (total 412 units) by a three-step purification procedure involving anion-exchange and size-exclusion chromatography. Thus, filtrated protein aliquots of C. aureogranulatus’s culture extract was applied to the first chromatographic step on the weak anion exchanger DEAE-Sepharose and most of the dark polyphenolic pigments could be removed from the CDH-exhibiting protein fraction. Thereby, the specific activity of CDH increased 5.6-fold from 0.7 to 3.8 U mg−1. The next purification step was performed on a Superdex™ 75 column and resulted in a significant increase of the specific activity of CauCDH (up to 30.9-fold), but also in a decrease of its total activity from 889 to 549 U.

The purity of C. aureogranulatus CDH (CauCDH), after the final step on HiTrap™ Q (Fig. 2a) columns, was assessed by 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis, which revealed a distinct band with apparent molecular mass of 109 kDa. Purified CauCDH exhibited a weak acidic pI of 5.4 appearing as one homogeneous protein band in the corresponding native IEF gel after staining with colloidal blue (Fig. 2b). The purification results are summarized in Table 1.

FPLC elution profile of the final purification step of CauCDH performed on HiTrap™ Q a column: absorbance at 280 nm (solid line), CDH activity (black circles), and NaCl gradient (dashed line). b SDS-PAGE (left) and native isoelectric focusing (right) of purified CauCDH (lane 2, 3); lanes 1 and 4, protein markers. c Spectra of the oxidized (black line) and reduced (grey line) states of CauCDH

Figure 2c shows the UV–visible spectrum of purified CauCDH with the typical characteristics of a flavocytochrome-heme CDH. Thus, the Soret band at 422 nm of the oxidized enzyme indicates the heme b cofactor, while the broad shoulder between 450 and 500 nm is indicative for a reduced Flavin (FAD) [3, 26]. The enzyme preparation had a high purity with an A420/A280 ratio of 0.6, which is within the range of data reported previously for other fungal CDHs [28, 29].

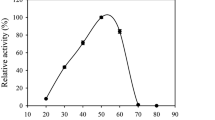

The highest relative activities of CauCDH were observed at 50 °C and pH 5.5. The enzyme activity slightly decreased under suboptimal conditions, e.g., ≤ 15% activity loss at 45 °C and 55 °C as well as at pH 5.0 and 6.0, respectively. A temperature of 70 °C caused a 50% activity loss within 2 h, and at 40 °C, over 50% of the initial activity was still detectable after 12 h of incubation. CauCDH activity significantly decreased after 2 h incubation at 70 °C probably due to less efficient interdomain electron transfer between heme and flavin of CDH [3]. The enzyme seems to be relatively stable at acidic and neutral conditions (i.e., pH 4.0–7.0) but lost about 80% of its activity within 2 h at pH 8.0 (Fig. 3).

Effects of temperature (at pH 5.5; a and pH (at 25 °C; b on the activity and stability of CauCDH at different temperatures c and pH-values (d); c 25 °C (circles), 40 °C (diamonds), 70 °C (triangles) at pH 5.5; d pH 8.0 (diamonds), pH 7.0 (triangles), pH 4.0 (circles) at 25 °C in 100 mM citrate/phosphate buffers. All experiments were performed in triplicates, standard deviation (SD) < 5%

Kinetic parameters and substrate specificities

As summarized in Tables 2 and 3, the broad substrate spectrum of purified CauCDH becomes evident by its ability to catalyze the oxidization of different β-1–4 linked di- and oligosaccharides (cellobiose, cellotriose, cellotetraose, lactose), whereas conversion and affinity of/for the α-1,4-linked disaccharide maltose as well as for monosaccharides such as mannose and glucose was low. Michaelis–Menten constants (Km = 117.1 up to 1,354,000 µM) and catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km values from 25.8 × 104 to 21.7 M−1 s−1 for cellobiose and maltose, respectively) could be determined for all tested substrates. The highest affinity (Km = 117.1 µM) and catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km = 25.8 × 104 M−1 s−1) was ascertained for cellobiose, which is also thought to be the physiological substrate of CauCDH. Lactose used to assay CDH activity turned out be in fact a rather suitable substrate for this purpose with a high specific activity (39.3 U mg−1) and appreciable turnover number (kcat = 61.7 s−1).

Two-electron acceptors such as cyt c and DCIP showed nearly identical Km values (1.3 and 1.6 µM, respectively), whilst a much higher Km was observed for another acceptor, i.e., potassium ferricyanide (18.5 µM). Moreover, the enzyme acted just poorly on one-electron acceptors such as 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone and 2,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone with Km-values around 300 µM.

Optimization of enzymatic conversion

Predicted model and statistical analysis

The fundamental levels and ranges of the reaction parameters were derived from the results of single factor investigation, of which the ratio of each enzyme activity to straw substrate (i.e., Cell/Xyl, AE, and CauCDH; U g−1) was selected as independent variable. In general, the most significant increase of metabolites (monosaccharides, carboxylic acid) could be observed at the enzyme ratios up to 18 U g−1 for Cell/Xyl, 35 U g−1 for AE, and 50 U g−1 for CauCDH. As the higher relative enzyme ratios led to only a slight increase of the released metabolites (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). Accordingly, three ratios of each enzyme were chosen as the survey area of the input parameters to create an experimental design matrix, such as 12, 18, 24 U g−1 of Cell/Xyl, 25, 35, 45 U g−1 of AE, and 40, 50, 60 of CauCDH, which corresponded to the low level (-1), the baseline (0), and the high level (+ 1), respectively (Additional file 1: Table S1). The dependent variables, i.e., the yields (Y) of released glucose (mg g−1), xylose (mg g−1), and gluconic acid (mg g−1) were determined experimentally as shown in the experimental design matrix (Additional file 1: Table S2). The model outcomes from analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the objective functions (product yields after enzymatic conversion) were evaluated using the F-value, p-value, and R2-value (Additional file 1: Table S3). The predicted responses of the three objective functions Y1, Y2, and Y3 and the independent variables related by quadratic polynomial equations were given (Additional file 1: Table S4). ANOVA of the quadratic regression model demonstrated that all three models corresponding to three objective functions fitted well and were highly significant. The F-values of the Y1, Y2 and Y3 were 84.44, 110.35 and 38.60, respectively, and the p-value was less than 0.05 indicating all models to be statistically significant. The model coefficients of determination (R2) were 0.9835, 0.9850 and 0.9858, respectively, suggesting that most of the yield variability can be explained by the experimental data. These data support the accuracy of the established model as well as confirm a high agreement between the measured and theoretically calculated data.

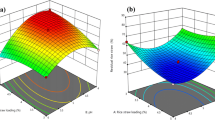

Response surface analysis

The estimated quadratic model was analyzed and plotted by using Design Expert 7.0.0 software. The x- and y-axes of 3D responsive surfaces represent the interaction of couple process parameters, i.e., the interaction of Cell/Xyl and AE (CauCDH, 50 U g−1); Cell/Xyl and CauCDH (AE, 35 U g−1); AE and CauCDH (Cell/Xyl, 18 U g−1). The z-axis represents one of three evaluation indices (Y1-glucose, Y2-xylose, and Y3-gluconic acid) and was reserved for the predicted response, resulting in three separate plots. The 3D response surfaces were constructed as shown in Fig. 4. It could be realized that the two-way interaction affected all objective functions in descending order by AB > BC > AC. This is consistent with the descending influence of single parameters in order of B > A > C (the coded variables of AE, Cell/Xyl, and CauCDH, respectively) as shown in the quadratic equations (Additional file 1: Table S4). As shown in Fig. 4a, b, an improvement in the objective functions, i.e., Y1 and Y2, could be reached following with the increased values of the single parameters A, B, C and vice versa. Uniquely, the Y3 was improved following the increase of the single parameters A and B only, while it reduced with a raise of the parameter C (Fig. 4c). Thus, there was a direct correlation between the objective functions (i.e., Y1, Y2, and Y3; Fig. 4) and the single parameters (A, B, and C) of the model equations as shown in the Additional file 1: Table S4. Of which, the influence of square parameters A2, B2, C2 was insignificant in comparison to A, B, and C, respectively, due to their variety to be in the range of (-1, + 1).

Optimization and model verification

The desired function was used to optimize the objective functions after the enzyme catalyzed process with the expectation for the Y1, Y2, and Y3 can reach the maximum values. As the result, 10 experimental options were found, of which the best plan to maximize the predicted objective function (as shown in Fig. 5). Thus, the optimal values of the objective functions were Y1 = 165,689, Y2 = 65.56, Y3 = 5.26 (mg g−1); and the values of the encoded variables at the optimal conditions were A = 0.2, B = 0.38 and C = 0.28, respectively. Then, the real variables were determined according to formula (2) to be 19.2 U g−1 for Cell/Xyl, 38.8. U g−1 for AE, and 52.8 U g-1 for CauCDH, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S5). The experimental values at optimal conditions were compared with the predicted values to determine the validity of the model, which exhibited a negligible difference (Additional file 1: Table S6). This again confirms that the construction model was compatible with the experimental conditions.

After optimization of three dependent variables, the optimal factors were determined to be 19.2 U g−1 for Cell/Xyl, 38.8 U g−1 for AE, and 52.8 U g−1 for CauCDH after incubating the rice straw for 48 h at 45 °C and pH 5.0. Accordingly, the objective functions were determined to be 165.18 ± 3.19; 64.21 ± 1.22, and 5.17 ± 0.13 (mg g−1) for glucose, xylose, and gluconic acid.

Discussion

Most efficient lignocellulolytic fungi are found among the basidiomycetous fungi degrading all components of lignocellulose and hence most of the characterized CDHs have been isolated from this group of fungi. In the present study, a successful purification strategy involving different steps of anion-exchange and size exclusion chromatography was developed to obtain a homogeneous CDH protein with high activity from solid-state cultures of the agaricomycete Coprinellus aureogranulatus (CauCDH). The approx. 42-fold purified CauCDH recovered after the final step on a HiTrap™ Q column was comparatively high with a yield of 22.7%. Thus, the recovery of purified CauCDH is comparable to percentages reported for the CDHs from the polypores Cerrena unicolor [28] and Trametes hirsuta [10] and the agaric Termitomyces clypeatus [30], but higher than that reported for the CDH of another polypore, Pycnoporus sanguineus (14.7%) [31]. The specific activity (28.9 mg−1 at pH 5.0 and 37 °C) of purified CauCDH for DCIP was found to be noticeably higher than the respective activities of other CDHs from basidiomycetous fungi [10, 29, 30]. In general, however, the physical and catalytic properties of CauCDH, i.e., MW (109 kDa), pI (5.4), optimum pH and temperature (pH 5.5 and 50 °C, respectively), have been expectable and within the range of reported values for other basidiomycetous CDHs, such as of P. chrysosporium [32], Schizophyllum commune [11], T. hirsuta [10], and Trametes versicolor [33].

Among the various carbohydrates tested, di- and oligosaccharides with β-(1,4) glycosidic bonds were the best substrates, for which CauCDH exhibited high specific activities, whereas substrates with α-(1,4)-interlinkages as well as monosaccharides were just converted very slowly and with low catalytic efficiencies. Thus, CDHs preferably catalyse the oxidation of soluble β-(1,4)-linked saccharides over that of monosaccharides, which seems to be an inherent property of this fungal enzyme type [34]. Increasing the number of glucosyl units in the cello-oligosaccharides tested resulted in decreasing substrate affinity (higher Km values) and lower catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km). This phenomenon has also been observed for other CDHs such as those from Volvariella volvacea [5] and T. clypeatus [30]. Although lactose is structurally similar to cellobiose and CauCDH exhibited the highest specific activity and turnover number for this substrate (39.3 U mg−1 and 61.7 s−1, respectively) along with high catalytic efficiency (84.5 × 103 M−1 s−1) and moderate affinity (Km = 731 µM), cellobiose is without doubt the physiological (i.e., natural) substrate of the enzyme, with the highest affinity and catalytic efficiency of all sugars tested (Km = 117.1 µM, kcat/Km = 25.8 × 104 M−1 s−1) and appreciable turnover number (30 s−1) and specific activity (28.9 U mg−1). In this context, kinetic properties of CauCDH are consistent with those of the Class-II basidiomycetous CDHs, which exhibit higher affinities and turnover numbers for cellobiose than basidiomycetous Class-I CDHs do [3]. The enzyme acted poorly on the electron acceptors 2,6-dimethyl-1,4-benzoquinone and 2,6-dimethoxy-1,4-benzoquinone with one to two orders of magnitude higher Km-values compared to other acceptors (cyt c, DCIP, 1,4-benzoquinone) examined. We assume that substitution of 1,4-benzoquinone with two methyl or methoxy groups caused a drastic activity reduction due to steric hindrance that was also observed for a CDH from the corticoid plant pathogen Sclerotium (Athelia) rolfsii [35].

The ability of purified CauCDH to catalyze the conversion of the lignocellulosic material as an auxiliary enzyme in cooperation with polysaccharide hydrolases, i.e., cellulase/xylanase (Cell/Xyl) and acetyl esterase (AE), was tested with rice straw as target, without any chemical pre-treatment. As main metabolites, glucose, xylose, and gluconic acid were detected, which are all biotechnological interest (as renewable resources for subsequent biological or chemical conversions). Thus, supplementation of purified CDH to the optimized rice-straw reaction setup, led to a moderate but significant increase of all product yields. Cellobiose accumulation during the hydrolytic process may have caused a feedback inhibition of cellobiohydrolases and endoglucanases. It is reasonable to assume that the role of fungal CDHs is to facilitate lignocellulose degradation for the concomitant attack, depolymerizing enzymes. Similar effects were reported for the synergistic acting CDHs from P. chrysosporium [36] or V. volvacea [5] and cellulases from T. reesei. Here, carbohydrate yields were increased by adding CDH, resulting in an increased formation of gluconic acid due to the hydrolysis of cellobionic acid by β-glucosidase that was also present in the T. reesei enzymatic cocktail [37]. In addition, the desired enzymatic activity/function was applied in this study to optimize the objective functions (i.e., the yields of carbohydrates and gluconic acid) during the enzyme-catalyzed process with the expectation of their max values will reach. Accordingly, the conversion of rice straw meal by hydrolyzing enzymes, i.e., cellulases, xylanases (Cell/Xyl), and/or acetyl esterase (AE), in the presence of CauCDH could be optimized with increased amounts of released C-5 and C-6 sugars (glucose, xylose) as well as of gluconic acid.

Future approaches in the field of lignocellulose conversion by CDH-containing enzymatic cocktails should include LPMOs, the most probable physiological partners of CDHs.

References

Abraham A, Mathew AK, Sindhu R, Pandey A, Binod P (2016) Potential of rice straw for bio-refining: an overview. Bioresour Technol 215:29–36

Goodman BA (2020) Utilization of waste straw and husks from rice production: a review. J Biores Biopro 5:143–162

Harreither W, Sygmund C, Augustin M, Narciso M, Rabinovich ML, Gorton L, Haltrich D, Ludwig R (2011) Catalytic properties and classification of cellobiose dehydrogenases from ascomycetes. Appl Envir Microbiol 77:1804–1815

Scheiblbrandner S, Ludwig R (2020) Cellobiose dehydrogenase: bioelectrochemical insights and applications. Bioelectrochem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioelechem.2019.107345

Chen K, Liu X, Long L, Ding S (2017) Cellobiose dehydrogenase from Volvariella volvacea and its effect on the saccharification of cellulose. Proces Biochem 60:52–58

Rai R, Basotra N, Kaur B, Falco MD, Tsang A, Chadha BS (2020) Exoproteome profile reveals thermophilic fungus Crassicarpon thermophilum (strain 6GKB; syn. Corynascus thermophilus) as a rich source of cellobiose dehydrogenase for enhanced saccharification of bagasse. Biomas Bioenerg. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2019.105438

Baldrian P, Valášková V (2008) Degradation of cellulose by basidiomycetous fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:501–521

Cameron MD, Aust SD (2001) Cellobiose dehydrogenase-an extracellular fungal flavocytochrome. Enzym Microb Technol 28:129–138

Bao W, Usha S, Renganathan V (1993) Purification and characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenase, a novel extracellular hemoflavoenzyme from the white-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch Biochem Biophys 300:705–713

Nakagame S, Furujyo A, Sugiura J (2006) Purification and characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenase from white-rot basidiomycete Trametes hirsuta. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 70:1629–1635

Fang J, Liu W, Gao P (1998) Cellobiose dehydrogenase from Schizophyllum commune: Purification and study of some catalytic, inactivation, and cellulose-binding properties. Arch Biochem Biophys 353:37–46

Ayers AR, Ayers SB, Eriksson KE (1978) Cellobiose oxidase, purification and partial characterization of a hemoprotein from Sporotrichum pulverulentum. Eur J Biochem 90:171–181

Fähnrich P, Irrgang K (1982) Conversion of cellulose to sugars and cellobionic acid by the extracellular enzyme system of Chaetomium cellulolyticum. Biotechnol Lett 4:775–780

Coudray MR, Canevascini G, Meier H (1982) Characterization of a cellobiose dehydrogenase in the cellulolytic fungus Sporotrichum (Chrysosporium) thermophile. Biochem J 203:277–284

Schou C, Christensen HM, Schulein M (1998) Characterization of a cellobiose dehydrogenase from Humicola insolens. Biochem J 330:565–571

Schmidhalter DR, Canevascini G (1993) solation and characterization of the cellobiose dehydrogenase from the brown-rot fungus Coniophora puteana (Schum ex Fr.) Karst. Arch Biochem Biophys 300:559–563

Giap VD, Hiep TTM, Nghi DH (2020) Cellulose-dehydrogenase production by some fungal species isolated in rain forests of northern Vietnam. Vietnam J Biotechnol 18:135–145

Nghi D, Ullrich R, Moritz F, Huong L, Giap V, Chi D, Hofrichter M, Liers C (2015) The ascomycete Xylaria polymorpha produces an acetyl esterase that solubilises beech wood material to release water-soluble lignin fragments. Appl Biol Chem 58:415–421

White T, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor F, White TJ, Lee SH, Taylor L, Taylor JS (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. Academic Press, New York

Jobb G, Haeseler A, Strimmer K (2011) TREEFINDER: a powerful graphical analysis environment for molecular phylogenetics. BMC Evol Biol 4:9–18

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP (2003) Mr BAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinform 19:1572–1574

Rambaut A, Drummond AJ, Xie D, Baele G, Suchard MA (2018) Posterior summarisation in Bayesian phylogenetics using Tracer 1.7. Syst Biol 67:901–904

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Molecul Biolog Evolut 33:1870–1874

Harreither W, Sygmund C, Dunhofen E, Vicuña R, Haltrich D, Ludwig R (2009) Cellobiose dehydrogenase from the ligninolytic basidiomycete Ceriporiopsis subvermispora. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:2750–2757

Nghi DH, Bittner B, Kellner H, Jehmlich N, Ullrich R, Pecyna MJ, Nousiainen P, Sipilä J, Huong LM, Hofrichter M, Liers C (2012) The wood-rot ascomycete Xylaria polymorpha produces a novel GH78 glycoside hydrolase that exhibits α-L-rhamnosidase and feruloyl esterase activity and releases hydroxycinnamic acids from lignocelluloses. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:4893–4901

Zhang R, Fan Z, Kasuga T (2011) Expression of cellobiose dehydrogenase from Neurospora crassa in Pichia pastoris and its purification and characterization. Protein Express Purif 75:63–69

Huang M, Bau T (2018) New findings of Coprinellus species (Psathyrellaceae, Agaricales) in China. Phytotaxa 374:119–128

Sulej J, Janusz G, Osińska-Jaroszuk M, Rachubik P, Mazur A, Komaniecka I, Choma A, Rogalski J (2015) Characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenase from a biotechnologically important Cerrena unicolor strain. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 176:1638–1658

Ludwig R, Salamon A, Varga J, Zamocky M, Peterbauer C, Kulbe K (2004) Characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenases from the white-rot fungi Trametes pubescens and Trametes villosa. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 64:213–222

Saha T, Ghosh D, Mukherjee S, Bose S, Mukherjee M (2008) Cellobiose dehydrogenase production by the mycelial culture of the mushroom Termitomyces clypeatus. Proces Biochem 43:634–641

Sulej J, Janusz G, Osińska-Jaroszuk M, Małek P, Mazur A, Komaniecka I, Rogalski J (2013) Characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenase and its FAD-domain from the ligninolytic basidiomycete Pycnoporus sanguineus. Enzym Microb Technol 53:427–437

Lehner D, Zipper P, Henriksson G, Pettersson G (1996) Small-angle X-ray scattering studies on cellobiose dehydrogenase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Biochem Biophys Acta 1293:161–169

Roy BP, Dumonceaux T, Koukoulas AA, Archibald FS (1996) Purification and characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenases from the white rot fungus Trametes versicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:4417–4427

Kracher D, Ludwig R (2016) Cellobiose dehydrogenase: an essential enzyme for lignocellulose degradation in nature—a review. J Land Manag Food Environ 67:145–163

Baminger U, Subramaniam SS, Renganathan V, Haltrich D (2001) Purification and characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenase from the plant pathogen Sclerotium (Athelia) rolfsii. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:1766–1774

Wang M, Lu X (2016) Exploring the synergy between cellobiose dehydrogenase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium and cellulase from Trichoderma reesei. Front Microbiol 7:620

Bey M, Berrin JG, Poidevin L, Sigoillot JC (2011) Heterologous expression of Pycnoporus cinnabarinus cellobiose dehydrogenase in Pichia pastoris and involvement in saccharification processes. Microb Cell Fact 10:1–15

Acknowledgements

This research is partly funded by Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) under grant number FWO.104.2017.03, and Ministry of Science and Technology (NĐT.45.GER/18), as well as the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) VnmDiv 031B0627 and CEFOX 031B0831B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DHN, MH, HK project design and funding acquisition. DHN, HK, TTNH, DTQ, CL experimental performance, data analysis, and manuscript preparation. LMH, AV, LD, CL, MH, participated in data analysis and manuscript revision. LXD joined in experimental design for optimization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

13765_2021_637_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region of nuclear DNA (rDNA) was used to identify fungal taxonomy of MPG14. Fig. S2. Single factor investigations of the effect of enzyme ratio (units per gram substrate; U g-1) on the yields of carbohydrates [glucose (diamond; mg g-1), xylose (triangle; mg g-1)] and gluconic acid (circle; mg g-1). A The effect of various Cell/Xyl ratio and fixed AE (25 U g-1) and CaCDH (40 U g-1); B The effect of various AE ratio and fixed Cell/Xyl (18 U g-1) and CaCDH (40 U g-1); C The effect of various CaCDH ratio and fixed Cell/Xyl (18 U g-1) and CaCDH (40 U g-1). Table S1. Ranges of parameters determined by experimental design. Table S2. Empirical data compared with actual and predicted response values. Table S3. Regression coefficients of the predicted second-order polynomial models for the amount of released glucose (Y1), xylose (Y2) and gluconic acid (Y3). Table S4. Empirical second-order polynomial models of the glucose (Y1), xylose (Y2) and gluconic acid content (Y3). Table S5. Values of the independent variable and real variables. Table S6. Predicted response values and experimental response values obtained under optimum conditions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nghi, D.H., Kellner, H., Büttner, E. et al. Cellobiose dehydrogenase from the agaricomycete Coprinellus aureogranulatus and its application for the synergistic conversion of rice straw. Appl Biol Chem 64, 66 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-021-00637-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-021-00637-y