Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of alcohol-based hand rubs (ABHRs) depends substantially on their acceptability and tolerability. In this study, we assessed the acceptability and tolerability of a new ABHR (product EU 100.2018.02).

Methods

Among physicians, nurses, and cosmetologists who used the ABHR for 30 days, we assessed the product’s acceptability and tolerability according to a WHO protocol. Additionally, we used instrumental skin tests. Participants assessed the product’s color, smell, texture, irritation, drying effect, ease of use, speed of drying, and application, and they gave an overall evaluation. Moreover, they rated the tolerability, i.e. their skin condition, on the following dimensions: intactness, moisture content, sensation, and integrity of the skin. The tolerability was also assessed by an observer as follows: redness, scaliness, fissures, and overall score for the skin condition. Instrumental skin tests included transepidermal water loss, skin hydration, sebum secretion, and percentage of skin affected by discolorations. All assessments were made at baseline (visit 1), and 3–5 days (visit 2) and 30 days (visit 3) later.

Results

We enrolled 126 participants (110 [87%] women) with a mean age of 34.3 ± 11.65 years. Sixty-five participants (52%) were healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses), and 61 (48%) were cosmetologists. During visit 2 and visit 3, about 90% of participants gave responses complying with the WHO’s benchmark for acceptability and tolerability. Similarly, the ABHR met the WHO criteria for observer-assessed tolerability: on all visits, in more than 95% of participants, the observer gave scores complying with the WHO benchmark. Transepidermal water loss decreased from baseline to visit 3 (p < 0.001), whereas skin hydration, sebum secretion, and the percentage of skin affected by discolorations did not change significantly during the study (p ≥ 130).

Conclusions

The EU 100.2018.02 had both high acceptability and tolerability, meeting the WHO criteria. The WHO protocol proved useful in the analysis of acceptability and tolerability of ABHRs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hand hygiene plays a central role in the prevention of infections, including those with multidrug-resistant pathogens [1, 2]. However, in healthcare and cosmetology, hand hygiene is insufficient, which is associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [3, 4].

Although consistent use of alcohol-based hand rubs (ABHR) improves hand hygiene substantially, poor acceptability and tolerability of ABHRs in the workplace is one of the most common causes of ineffective hand hygiene [5, 6]. Thus, acceptability and tolerability are important criteria for selecting ABHRs, and high acceptability and tolerability help maintain hand hygiene practices [7,8,9]. In 2009, the WHO put forward both a protocol and criteria for assessing the acceptability and tolerability of ABHRs [10].

In this study, we evaluated the acceptability and tolerability of a new ABHR (product EU 100.2018.02) among healthcare professionals and cosmetologists. We followed the WHO protocol and used additional instrumental skin tests.

Methods

Participants

We enrolled adult participants (> 18 years) among physicians and nurses of a gynecological ward and among cosmetologists of a private clinic. We excluded people with skin diseases or known hypersensitivities to the ingredients of the investigational product. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw (KB213/2018). All participants signed informed consent before enrollment. Basic characteristics of participants were gathered in accordance with the WHO protocol [10].

Investigational product

The investigational product, an ABHR (EU 100.2018.02, HCS Europe, Poland), complied with the EN 1500:2013–07 and EN 12791 + A1:2017–12 standards. The ABHR contained ethanol CAS 64–17-5 (80 g/100 g), vegetable glycerin, vitamin E, bisabolol, and flavonoids.

Study procedures

The study assessed the tolerability and acceptability of the investigational product according to the protocol proposed by the WHO [10]. Briefly, on a seven-point Likert scale, participants rated the product’s:

color (“unpleasant”-“pleasant”),

smell (“unpleasant”-“pleasant”),

texture (“sticky”-“non-sticky),

irritation (“very irritating”-“not irritating”),

drying effect (“very much”-“not at all”),

ease of use (“very difficult”-“very easy”),

speed of drying (“very slow”-“very fast”),

application (“unpleasant”-“pleasant”), and.

overall evaluation (“dissatisfied”-“satisfied”).

Similarly, on a seven-point Likert scale, participants assessed the skin condition of their hands:

appearance (“abnormal”-“normal”);

intactness (“abnormal”-“normal”);

moisture content (“abnormal”-“normal”);

sensation (“abnormal”-“normal”);

overall integrity of the skin (“very altered”-“not altered”).

Skin condition was also rated by an observer, as follows:

redness (0–4, no redness-very bright with edema),

scaliness (0–3, no scaliness-very pronounced separation from skin),

fissures (0–3, no fissure-extensive cracks with bleeding or seeping), overall

overall score for the skin condition (0, no observable scale or irritation of any kind; 1, occasional scale that is not necessarily uniformly distributed; 2, dry skin and/or redness; 3, very dry skin with whitish appearance, rough to touch, and/or redness, but without fissures; 4, cracked skin surface but without bleeding/seeping; 5, extensive cracking of skin surface with bleeding/seeping).

All evaluations were carried out at baseline and 3–5 and 30 days after using the ABHR. All participants used 30 ml or more of the ABHR daily. Each participant received a personal container of the ABHR. Participants were allowed to use hand lotion or hand cream throughout the study.

Instrumental skin assessments

During all three visits, the skin on hands was assessed with an MPA-5 Corneometer to evaluate skin hydration; an MPA-5 Sebumeter to evaluate sebum secretion; a TM300 Tewameter with a cylindrical probe to evaluate transepidermal water loss; and a Derma Visualizer camera to assess the percentage of skin affected by discolorations (all devices by Courage & Khazaka, Cologne, Germany). The Corneometer measures hydration in the stratum corneum of the epidermis based on the electrical properties of the skin; skin hydration is reported in units from 0 to 130 (each unit indicates 0.02 mg of water per square centimeter of the stratum corneum). The Sebumeter measures sebum content in a foil attached previously to the skin for 30 s; the results range from 0 to 350 micrograms of sebum per square centimeter of skin. The Tewameter estimates transepithelial water loss based on the skin’s wetness and temperature, which are used to calculate water vapor pressure. Transepithelial water loss is reported in g/m2/h, with higher values indicating worse skin hydration. The Derma Skin Visualizer uses parallel and crossed polarized light to measure pigment discoloration on the skin; the result is given as the percentage of the studied area with discolorations.

End points

The WHO criteria for product acceptability were as follows:

≥ 50% of participants responding above 4 for “Color” and “Smell”, and ≥ 75% of participants responding above 4 for “Texture”, “Irritation”, “Drying effect”, “Ease of use”, “Speed of drying”, “Application”, and “Overall evaluation”.

The WHO criteria for skin tolerability were as follows:

≥ 75% of participants responding above 4 for the skin’s “Appearance”, “Intactness”, “Moisture content”, “Sensation”, and “Overall integrity”

≥ 75% of participants with scores below 2 on the skin evaluation by the observer.

Statistical analysis

Variables are presented as counts and percentages or as means±standard deviations (SD). Comparisons were carried out with repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc Scheffe contrasts. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All calculations were carried out with SPSS software (version 2018).

Results

Participants

We enrolled 126 participants (110 [87%] women) with a mean age of 34.3 ± 11.65 years. Sixty-five participants (52%) were healthcare professionals (physicians, nurses) and 61 (48%) were cosmetologists. Their mean professional experience was 9 ± 10 years; 88 (67%) participants worked full-time. Thirty-three (26%) participants had non-occupational activates that could damage skin, 10 (15%) participants declared frequent skin irritation, and 88 (70%) participants declared non-frequent skin irritation. Fifty-nine (48%) participants used ABHRs for five years or longer. Forty-five (36%) participants had Fitzpatrick skin type 1, 58 (46%) had Fitzpatrick skin type 2, and 23 (18%) had Fitzpatrick skin type 3. Table 1 shows the frequency of hand hygiene practices assessed during visit 3.

Self-assessed acceptability and tolerability of the product

During visit 2 and visit 3, the ABHR met the WHO criteria for self-assessed acceptability. More than 90% of participants gave responses of 4 or more to all questions about the product’s acceptability (Fig. 1). Similarly, the ABHR met the WHO criteria for self-assessed tolerability. About 90% or more participants gave responses of 4 or more to all questions about skin condition (Fig. 2).

Observer-assessed tolerability of the ABHR

The ABHR met the WHO criteria for observer-assessed tolerability. On all visits, in more than 95% of participants, the observer gave scores of ≤1 to all items that assessed skin tolerability (Table 2).

Instrumental skin assessments

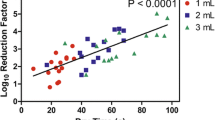

Transepidermal water loss decreased from baseline to visit 3 (p < 0.001); only the difference between visit 1 and visit 3 was significant on post-hoc comparisons (p < 0.05, Fig. 3 A). Skin hydration, sebum secretion, and number of discolorations on the skin on hands did not change significantly during the study (p ≥ 130, Fig. 3 B-D).

Discussion

This study showed that the investigational ABHR (EU 100.2018.02) had good acceptability and tolerability among healthcare professionals and cosmetologists. The ABHR met all WHO criteria for both acceptability and tolerability. Moreover, participants declared that the product could improve hand hygiene in their workplace.

Hand hygiene is insufficient among healthcare professionals and other staff [1]. For example, Anwar et al. found that hand hygiene is observed only 30% of the time [11]. Lack of time is one of the reasons for poor hand hygiene, which was observed among our participants and in previous studies [12, 13]. Over 80% of our participants admitted that a lack of time causes non-compliance with hand hygiene procedures.

Acceptability and tolerability of hand sanitizer products are also very important for consistent hand hygiene. Therefore, improvements in acceptability and tolerability can translate into fewer infections. Hand products, particularly those containing sodium laureth sulfates, irritate the skin and deplete skin lipids [14,15,16]. ABHRs seem to be better tolerated than detergents and are now recommended by the WHO as preferred hand sanitizers [17,18,19]. Because the skin tolerates ethanol better than n-propanol or isopropanol, ethanol is the preferred active substance in ABHRs (also included in the product tested in our study) [20, 21]. Additionally, ethanol has a potent killing effect against viruses [22]. Emollients or other skin conditioners can substantially reduce the skin drying effect of alcohol [23,24,25,26]. The investigational product in our study contained vegetable glycerin as a skin conditioner. Importantly, in developmental studies, glycerin did not reduce the bactericidal effect of the product. Moreover, bisabolol, another ingredient of the tested ABHR, has a soothing effect on the skin, in addition to its anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects [27].

Because ABHRs are important for hygiene, the WHO put forward both a protocol and criteria for assessing the acceptability and tolerability of these products. To our knowledge, only one published study followed this protocol. In that study, in contrast to our study, the product investigated did not meet all the WHO criteria for acceptability [28]. In the study by Wolsfensbergeret et al., the ABHR was too sticky, and it dried too slowly [28]. In contrast, in our study, more than 90% of participants were satisfied with the ABHR’s texture and speed of drying. Moreover, in more than 95% of participants in our study, the product’s tolerability complied with the WHO benchmark. We did not observe any adverse effects of the ABHR, although such products could induce, for example, contact dermatitis, phototoxicity, or pruritus.

We found that the ABHR significantly reduced transepidermal water loss over a month of use, although previous studies on ABHRs found no such effect [29, 30]. Moreover, the ABHR did not impair skin hydration or sebum secretion, nor did it induce skin discolorations. These findings are in line with the excellent acceptability and tolerability of the tested product reported by participants and the observer. However, one has to keep in mind that the study lasted for only one month, and skin condition could change over a longer period. Although the instrumental skin test enabled an objective assessment of skin condition, we needed twice as much time to complete all assessments compared to the WHO protocol alone.

In our study, each participant received a personal container of the tested ABHR, which could have had an effect of the perceived acceptability and tolerability. Wolsfensbergeret et al. found that hand sanitizers available from personal containers might improve self-reported assessments [28]. Participants in our study were allowed to used hand lotions or creams, which could have interfered with our assessments. Moreover, the study was carried out in the winter, which could have worsened the condition of the skin.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that the investigational ABHR (EU 100.2018.02) had high acceptability and tolerability. Thus, it could improve hand hygiene. The WHO protocol proved to be a useful tool in the analysis of acceptability and tolerability of ABHRs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABHR:

-

alcohol-based hand rub

- EU:

-

European Union

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Boyce J, World Health Organization World Alliance for Patient Safety First Global Patient Safety Challenge Core Group of Experts. The World Health Organization Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care and Their Consensus Recommendations. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Jul 2];30:611–22. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19508124.

Gerberding JL, Director David Fleming MW, Snider DE, Thacker SB, Ward JW, Hewitt SM, et al. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings recommendations of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA hand hygiene task force Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [internet]. 2002. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5116.pdf

Oliveira AC, Focaccia R. Survey of hepatitis B and C infection control: procedures at manicure and pedicure facilities in São Paulo, Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2019 Jul 2];14:502–7. Avaiable from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21221480.

Garbaccio JL, de Oliveira AC. Adherence to and knowledge of best practices and occupational biohazards among manicurists/pedicurists. Am J Infect Control [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2019 Jul 2];42:791–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24799121.

Grayson ML, Russo PL, Cruickshank M, Bear JL, Gee CA, Hughes CF, et al. Outcomes from the first 2 years of the Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative. Med J Aust [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Jul 2];195:615–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22107015.

Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Sax H, Chraiti M-N, Griffiths W, Richet H, et al. Double-Blind, Randomized, Crossover Trial of 3 Hand Rub Formulations: Fast-Track Evaluation of Tolerability and Acceptability. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2019 Jul 2];28:1344–51. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17994514.

Ho M, Seto W, Wong L, Wong T. Effectiveness of Multifaceted Hand Hygiene Interventions in Long-Term Care Facilities in Hong Kong: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Jul 2];33:761–7. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0195941700031234/type/journal_article

Yeung WK, Tam WSW, Wong TW. Clustered Randomized Controlled Trial of a Hand Hygiene Intervention Involving Pocket-Sized Containers of Alcohol-Based Hand Rub for the Control of Infections in Long-Term Care Facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2019 Jul 2];32:67–76. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21087125.

Behnke M, Gastmeier P, Geffers C, Mönch N, Reichardt C. Establishment of a National Surveillance System for Alcohol-Based Hand Rub Consumption and Change in Consumption over 4 Years. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Jul 2];33:618–20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22561718.

The World Health Organisation. Protocol for Evaluation of tolerability and acceptability of alcohol-based handrub in use or planned to be introduced: Method 1 [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2019 Jun 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Protocol_for_Evaluation_of_Handrub_Meth1.doc?ua=1

Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 16];388:1545–602. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27733282.

Pittet D. Compliance with hand disinfection and its impact on hospital-acquired infections. J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2019 Jul 2];48:S40–6. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S019567010190012X

Awoke N, Geda B, Arba A, Tekalign T, Paulos K. Nurses Practice of Hand Hygiene in Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harari Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia: Observational Study. Nurs Res Pract [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 2];2018:1–6. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/nrp/2018/2654947/

Pedersen LK, Held E, Johansen JD, Agner T. Short-term effects of alcohol-based disinfectant and detergent on skin irritation. Contact Dermatitis [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2019 Jul 2];52:82–7. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00504.x

Pedersen LK, Held E, Johansen JD, Agner T. Less skin irritation from alcohol-based disinfectant than from detergent used for hand disinfection. Br J Dermatol [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2019 Jul 2];153:1142–6. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06875.x

Kaiser NE, Newman JL. Formulation technology as a key component in improving hand hygiene practices. Am J Infect Control [Internet]. Elsevier; 2006 [cited 2019 Jul 2];34:S82–97. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0196655306009515

Löffler H, Kampf G. Hand disinfection: How irritant are alcohols? J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2019 Jul 2];70:44–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0195670108600109

Kampf G. Dermatological aspects of a successful introduction and continuation of alcohol-based hand rubs for hygienic hand disinfection. J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 2003;55:1–7. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0195670103002238

Winnefeld M, Richard MA, Drancourt M, Grob JJ. Skin tolerance and effectiveness of two hand decontamination procedures in everyday hospital use. Br J Dermatol [Internet] 2000;143:546–550. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2000.03708.x

Cartner T, Brand N, Tian K, Saud A, Carr T, Stapleton P, et al. Effect of different alcohols on stratum corneum kallikrein 5 and phospholipase a 2 together with epidermal keratinocytes and skin irritation. Int J Cosmet Sci [Internet] 2017;39:188–196. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12364

Houben E, De Paepe K, Rogiers V. Skin condition associated with intensive use of alcoholic gels for hand disinfection: a combination of biophysical and sensorial data. Contact Dermatitis [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2019 Jul 2];54:261–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16689810.

Kampf G. Efficacy of ethanol against viruses in hand disinfection. J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 2018;98:331–8 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0195670117304693.

Ahmed-Lecheheb D, Cunat L, Hartemann P, Hautemanière A. Prospective observational study to assess hand skin condition after application of alcohol-based hand rub solutions. Am J Infect Control [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Jul 2];40:160–4. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0196655311006870

Kramer A, Bernig T, Kampf G. Clinical double-blind trial on the dermal tolerance and user acceptability of six alcohol-based hand disinfectants for hygienic hand disinfection. J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2019 Jul 2];51:114–20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12090798.

Kanlayavattanakul M, Rodchuea C, Lourith N. Moisturizing effect of alcohol-based hand rub containing okra polysaccharide. Int J Cosmet Sci [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd (10.1111); 2012 [cited 2019 Jul 2];34:280–3. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2494.2012.00715.x

Ionidis G, Hübscher J, Jack T, Becker B, Bischoff B, Todt D, et al. Development and virucidal activity of a novel alcohol-based hand disinfectant supplemented with urea and citric acid. BMC Infect Dis [Internet]. 2016;16:77. Available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/16/77

Maurya A, Singh M, Dubey V, Srivastava S, Luqman S, Bawankule D. α-(−)-bisabolol reduces Pro-inflammatory Cytokine Production and Ameliorates Skin Inflammation. Curr Pharm Biotechnol [Internet]. 2014;15:173–81. Available from: http://www.eurekaselect.com/openurl/content.php?genre=article&issn=1389-2010&volume=15&issue=2&spage=173

Wolfensberger A, Durisch N, Mertin J, Ajdler-Schaeffler E, Sax H. Evaluating the tolerability and acceptability of an alcohol-based hand rub – real-life experience with the WHO protocol. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control [Internet]. 2015;4:18. Available from: https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-015-0052-9

Boyce JM, Kelliher S, Vallande N. Skin Irritation and Dryness Associated With Two Hand-Hygiene Regimens: Soap-and-Water Hand Washing Versus Hand Antisepsis With an Alcoholic Hand Gel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol [Internet]. 2000;21:442–8. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0195941700042764/type/journal_article

Kampf G. Dermal tolerance and effect on skin hydration of a new ethanol-based hand gel. J Hosp Infect [Internet]. 2002; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0195670102913113

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided by own sources. Linguistic support were funded by HCS Europe sp. z o.o. The funding source was not involved in study design, collection, and interpretation of the data, and manuscript submission. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PT, KG and A N-O participated in the planning and execution of the study. PT and A N-O performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. The manuscript was revised and approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Warsaw (KB213/2018). All participants singed informed consent before enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tarka, P., Gutkowska, K. & Nitsch-Osuch, A. Assessment of tolerability and acceptability of an alcohol-based hand rub according to a WHO protocol and using apparatus tests. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 8, 191 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0646-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0646-8