Abstract

Background

Microbial communities are crucial for ecosystems. A central goal of microbial ecological research is to simplify the biodiversity in natural environments and quantify the functional roles to explore how the ecosystems respond under different environmental conditions. However, the research on the stability and dynamics of lake microbes in response to repeated warming stress is limited.

Methods

To exclude confounding environmental factors, we conducted a 20-day repeated warming simulation experiment to examine the composition and function dynamics of lake microbial communities.

Results

Experimental warming significantly altered the community structure of bacteria instead of fungi. Microbial community structure, together with microbial biomass, jointly regulated the function of microbial communities. The plummeting of aerobic denitrifiers Pseudomonadaceae decreased by 99% (P < 0.001) after high temperature, leading to reduced microbial nitrogen metabolism on nitrogen respiration and nitrate respiration. Under warming conditions, the microbial community with higher adaptability showed more positive correlations and less competitive relationships in co-occurrence networks to acclimate to warming.

Conclusion

Microbiome composition controlled carbon and nitrogen metabolism, thus determining lake microbial communities’ adaptability to heat stress. This study extended our insights on the lake microbial community response and adaptability under warming drivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the core of the ecosystem, microorganisms are not only numerous but also have greater diversity than other organisms, which have made significant contributions to the biogeochemical cycles (e.g., nitrogen fixation, oxygen generation, and methane generation) (Shilky et al. 2023) and stability of ecosystem services (Fuhrman 2009; Graham et al. 2016). Understanding how climate changes determine the spatial and temporal diversity of microbial species is a central goal of microbial ecology.

Temperature, a main driving factor of global environmental changes, can affect the structures and ecological functions of microbiota (Bai et al. 2013; Gillooly et al. 2001). The response of microorganisms to warming varies greatly in both taxonomy and geography. For example, archaea methanogens are more abundant in lakes in warmer regions, and future methane emissions will be more controlled by archaea methanogens under global warming (Winder et al. 2023). Over the globe, the microbial carbon use efficiency is lower in lower-latitude regions, reflecting that microbes reduce the proportion of carbon allocated to organic synthesis to adapt to the high-temperature environment to maintain more energy required for metabolism (Tao et al. 2023). In the soil vertical profile, warming does not change the carbon use efficiency of microorganisms in surface and deep soil layers (Zhang et al. 2023a). From the secular variation of more than half a century, warming accelerates the growth, respiration, and uptake of microbial communities (Walker et al. 2018), while the short-term and local-area effects of temperature on ecosystems are still complex. On one hand, extreme warming could result in biodiversity loss and halting of biodiversity recovery (Haase et al. 2023), and weaken the ecosystem functions and services related to biodiversity (Guo et al. 2018, 2019). On the other hand, warming can alter microbial enzyme activity, accelerate microbial turnover, and promote carbon accumulation in the environment (Hagerty et al. 2014). The microbial network response could also be enhanced by warming, which results in higher community stability (Thébault and Fontaine 2010; Yuan et al. 2021). Even under stress conditions, well-adapted microbial communities have special mechanisms to maintain important biogeochemical processes (Lay et al. 2013; Zorz et al. 2019). At present, studies on the impact of warming on microbial communities are mostly focused on soil ecosystems, while only very few studies have a full understanding of the response of microorganisms to warming in aquatic environments. As one of the most sensitive ecosystems on Earth to environmental change (Dudgeon et al. 2006), lake ecosystems have species that are more susceptible to the negative consequences of environmental change than terrestrial and marine species (O’Reilly et al. 2015; Woolway and Maberly 2020). Therefore, understanding how microbial species respond to sustained climate change is crucial for assessing freshwater ecosystem vulnerability and avoiding potential biodiversity losses.

Previous studies have conducted many long-term in situ warming experiments to explore the warming-induced changes and mechanisms in microbial communities. Warming and concomitant decrease in soil moisture exacerbate the reduction of soil microbial biodiversity (Wu et al. 2022). In aquatic environments, warming-induced acceleration of organic carbon decomposition and the promotion of algae growth affect the response of microorganisms to environmental changes (Hu et al. 2024; Sarmento et al. 2016). In addition, the interaction between eutrophic water bodies and temperature can amplify the effects of warming and may also lead to high variability in the composition of planktonic bacterial communities (Cross et al. 2022; Ren et al. 2017). What’s more, the decrease in microbial diversity caused by early warming will change the microbial community composition and lead to the enrichment of thermophilic taxa (Nottingham et al. 2022). However, microbial communities are highly complex under inhabiting intricate natural environments. In situ experiments would be influenced by various factors so the work on establishing causal relationships between microbial communities, environmental conditions, and ecosystem functions is difficult (Pascual-Garcia and Bell 2020). Other big data-based research evaluated the microbial data and environmental variables at the global scale (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2019; Yang et al. 2019), while such inference of the correlations between species and climate conditions ignored potential biological mechanisms, such as biomass changes, species interactions, and so on. Laboratory microcosm experiments have a greater potential for understanding ecological communities than generally thought (Cadotte et al. 2005; Gilpin et al. 1986). The environment for laboratory community studies can be precisely controlled and easily replicated and can answer many fundamental ecological questions through the construction of rapidly growing species and communities (Jessup et al. 2004; Lawton 1998).

To investigate the adaptability of microbes and their metabolisms and functional potential in differential lake environments under repeated warming, we conducted a 20-day microcosm experiment to simulate the responses of river microbes to warming. According to the microbial activity monitoring and amplicon sequencing analyses, we identified the differences between microbial populations and communities in the ability to respond to warming. Combined with Biolog EcoPlate experiments and metabolomics, we identified which taxonomic groups may play a key role, and described the potential ecological important nutrient cycles that may exist. We investigated the adaptability of the microbial community level and the responsive changes of the microbial community function to repeated heat stress. The mechanistic insight identified by this study corroborates the stability and recovery dynamics of freshwater microbes under heat stress.

Materials and methods

Samples collection and microcosm experiments

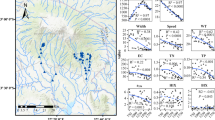

Due to the minimum temperature difference between the north and south of China, samples were collected during the summer (August 2020) at a depth of 0.5 m of 8 lakes in China (Additional file 1: Table S1) to present different microbial communities and physicochemical properties. All samples were transported on ice to Tianjin Key Laboratory of Environmental Remediation and Pollution Control in China and stored at 4 °C.

In this experiment, there was significant heterogeneity in the physicochemical property data of 8 lakes, making it difficult to elucidate the impact of environmental changes on microbial adaptability using natural lake samples. Microcosm experiments allow for the study of individual environmental change factors through simplified microbial ecosystems (Lü et al. 2022), providing strong support for studying the potential relationship between warming and microbial community changes. Microcosm experiments were guided by an original batch incubation (Valenzuela et al. 2018) to explore the adaptability of the microbial population. Based on meteorological data from the website of Chinese Weather (https://lishi.tianqi.com/), we calculated the monthly environmental temperature at sampling sites in August from 2011 to 2020. Considering that the highest monthly temperature at sampling sites was 35 °C, we set the ambient temperature at 25 °C and the warming temperature at 35 °C for the experiment (Renes et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2023). Lake samples were cultured in 10 mL round bottom centrifuge tubes with sterile artificial freshwater medium (Additional file 1: Table S2; Reasoner and Geldreich 1985) with a mean light intensity of 3000 lx under a 12:12 h light–dark cycle. The culturing tubes were covered with sterile sealing films to avoid microbial contamination but allow gas exchange. Microbes were first cultured for 5 days initial stage (Stage 0) to allow the microbial population to reach the stationary phase (Qu et al. 2023). Then, experiments were performed in triplicates for two control and warmed groups for 4 stages (every 5 days was one stage) and were kept under sterile and nutrient-replete growth conditions. During incubation, the microbial inoculum was homogenized by shaking centrifuge tubes every day. At the end of each stage, count living microbial cells with the flow cytometer (Accuri™ C6 Plus, BD, USA) to ensure the initial cell density in about 1 × 103 cells mL−1. Then transfer a small amount of cultures (approximately 5–30 μL) into a fresh medium to restart the growth in a new stage. The control groups were cultured under constant temperature at 25 °C, while warmed groups were under temperature stress (the temperature was 35 °C during stage 1 and stage 3) (Fig. 1A). In warmed groups, communities were at ambient temperature after high-temperature condition to assess whether microbes from the previous stage could recover from disturbance to an appropriate population growth state (Fig. 1A).

Experimental design. A The microcosm experiment began with the pre-incubation (stage 0) of lake samples. Then the culture was separated as the initial communities into control and repeated warmed groups for 20 days of incubation (stages 1–4). B According to the changing trend of microbial biomass and response ratio (see Additional file 1: Figure S1), two types of microbial communities (vulnerable and adaptive microbial communities) were selected in the microcosm experiment. In four-line charts, the gray column represents temperature variation; the solid lines and dotted lines represent microbial biomass trends

After the 20-day microcosm experiment, the natural logarithm of response ratio (RR) was used to measure the impact of experimental warming on microbes (Zhang et al. 2023b). RR was defined as the microbial living cells in the warmed groups divided by those in the control groups. If the lnRR value is greater than zero, it indicates that the experimental warming has a promoting effect on microbial growth. Previous researchers distinguished freshwater microbial communities based on net growth rate under temperature pulse conditions (Qu et al. 2023), and we defined the adaptability of microbial communities under experimental warming using the positive or negative response rate (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). In the four stages, if the lnRR values of two or more stages are greater than zero, it indicates that the microbial community has recovery and adaptability to experimental warming. On the contrary, it indicates that the microbial community is vulnerable and difficult to recover to the original state. Thus, the adaptive classification of microbial communities in our experiment was divided into two types: adaptive and vulnerable (Adger 2006; Brooks and Adger 2005). After incubation, two representative groups with significant differences were chosen to represent vulnerable and adaptive communities (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). 3.75 mL of cultures in each centrifuge tube (n = 54) was collected and centrifuged, and collected sediment was stored at – 80 °C for DNA extraction. Another 2.0 mL of cultures were collected, centrifuged, washed once by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and centrifuged, and the collected sediment was stored at − 80 °C for metabolites extraction. A total of 54 samples were constructed in this experiment, including 3 replicated samples for each of the two types of lake microbial communities at the initial stage, and 24 samples were collected in 4 stages of microcosmic experiment (3 × 4 controls and 3 × 4 repeated high-temperature treatments).

DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing

Microbial DNA was extracted from samples using the E.Z.N.A.® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Biotek, Norcross, GA, USA). Using a NanoDrop 2000 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA) to concentrate and purify DNA, with the DNA quality checking by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

The bacterial 16S rRNA and the fungal ITS genes were amplified with the primers 338F/806R and ITS3F/ITS4R, respectively. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation for 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 27 cycles for 30 s at 95 °C, annealing for 30 s at 55 °C and elongation for 45 s at 72 °C, with final extension for 10 min at 72 °C. The triplicate PCRs were performed, and PCR amplification was carried out in a 20 μL mixture according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplicons were extracted from 2% agarose gels and further purified. The purified amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts and paired-end sequenced (2 × 300) by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) on a platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). QIIME (version 1.17) was used to process raw FASTQ files.

After demultiplexed, quality-filtered by Trimmomatic and merged, the raw 16S rRNA and ITS gene sequencing reads generated 2,843,696 high-qualities sequences with 434 bp in length on average for 54 bacterial samples and 4,147,841 sequences with 319 bp in length on average for 54 fungal samples. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with a 97% similarity level were clustered by UPARSE (version 7.0.1090). RDP Classifier (version 2.11, with a confidence threshold of 0.7) analyzed the taxonomy of each representative OTU sequence against the Silva database (Release 138) and fungal OTU sequences against Unite database (Release 8.0). Finally, the microbial amplicon reads were normalized based on the minimum data of samples.

Microbial metabolic capacity experiments and analysis

The carbon metabolic fingerprints of the microbial community were indicated by EcoPlates (Biolog Inc., USA). The EcoPlates consist of 96 wells with 31 different carbon sources. Microbial suspensions were dispensed into 96 wells (150 μL per well with the initial microbial concentration of 1 × 104 cells mL−1) with another 3 blank samples. Then the incubation was at 25 °C in the dark for 5 days, and the optical denticity at 590 nm (OD590) of each well was read with a microplate reader (Synergy H4, Bio-Tec, USA) in 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h. Average well color development (AWCD) change rate of each hole on the microplates was used to evaluate the ability of microbial communities to utilize a single carbon source, i.e. the overall metabolic activity of microorganisms. Simpson’s diversity index (D) was calculated to evaluate the dominance of the most common species and to further analyze the functional diversity of communities. The equations were as follows:

where Ri is the OD590 of each well on the EcoPlates, R0 is the OD590 value of the control well (if Ri–R0 ≤ 0, R0 is regarded as 0), and N is the number of carbon sources in 32 holes on the EcoPlates, i.e. N = 31.

In the above formula, \({P}_{i}\) is the ratio of the difference of OD590 between the hole with carbon source and the control hole to the total difference of the whole plate, i.e. \(\frac{{R}_{i}-{R}_{0}}{\sum \left({R}_{i}-{R}_{0}\right)}\). \({R}_{{s}_{i}}\) is the standardized absorbance value. Based on the AWCD value, the utilization of various carbon substrates (at 120 h) by microorganisms was analyzed.

Metabolite extraction and LC/MS analysis

Refer to previous research (Meyer-Cifuentes et al. 2020), the metabolites in metabolomics analysis were extracted from the microbial pellets. Briefly, the cell pellets for metabolic extraction gained at the end of Sect. Samples collection and microcom experiments were resuspended in methanol and removing residual plastic film/particulate material. The supernatant was concentrated by using a vacuum centrifugal concentrator (SCIENTZ-1LS, Scientz, China). After two-step derivatization of adding methoxyamine hydrochloride dissolved in pyridine (20 mg/mL, 50 μL) and N-methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (80 μL), the injected samples were analyzed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC–MS, 6890A/5977A, Agilent, USA). Metabolic data was performed by a platform, called MetaboAnalyst (version 5.0, https://www.metaboanalyst.ca). Metabolites in significant differences were screened by volcano plots (FC > 2.0 or < 0.5) and T test with P < 0.05.

Statistical analyses

The microbial community structure composition at different taxonomic levels (e.g., phylum, family, and OTU) was performed by R (version 3.6.3). Qualified OTU data were used to calculate Chao1 index (microbial richness) and Shannon index (microbial diversity) by Mothur (version 1.30.2). Based on the normalized intensities of OTUs, the distribution of top OTUs in different groups was shown by enrichment charts made on an online tool ImageGP (Chen et al. 2022), and used hierarchical clustering analysis of pairwise Bray–Curtis distances to explore the similarity and difference among different groups of samples. Beta diversity (β-diversity) analysis was assessed and mapped by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). Using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) coupled with effect size measurements (LEfSe) analysis to describe the significant differences from phylum to OTU level. The OTUs data of bacteria and fungi were annotated with function information by matching with the functional annotation of prokaryotic taxa (FAPROTAX) database (Louca et al. 2016) and the FUNGuild database (http://www.funguild.org/). Co-occurrence analyses were constructed using the R package “Hmisc”. To reduce complexity, OTUs with a total abundance more than 50 were retained, and the OTU-based pairwise Spearman’s correlations were calculated (with the absolute value of a correlation coefficient > 0.6 and P < 0.05), then networks were visualized by Gephi (version 0.9.7). Mantel-test analysis was conducted using the R package “ggcor” and Spearman correlation analysis was used to present the relationship between microbial taxa and differential metabolites, which was performed by clustering correlation heatmaps using the OmicStudio (https://www.omicstudio.cn).

All experiments in our study were performed in triplicate, with the results as the means ± standard deviation (SD). The data was tested for normality and variance homogeneity, and then, data analysis was processed by IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 22.0) and Graphpad prism (version 8.0.2). The significant differences (P < 0.05) between the control and warmed groups were calculated by T-test, and one-way ANOVA test was used to seek significant differences between multiple groups.

Results

Changes in microbial community structure under warming

In the microcosm experiment, warming significantly influenced the relative abundance of the vulnerable community (P < 0.0001) with plummeting in microbial numbers, while that of adaptive communities increased relatively after disturbance (Fig. 1B). Compared with the control, microbial biomass of both communities was in great hit under the first high-temperature disturbance (Fig. 1B, stage 1). The microbial biomass of the vulnerable community was near to collapse and hard to recover during cushioning periods (hollow circles and dash lines in red, in stage 2 and stage 4), while the biomass of the adaptive community was in steady-state growth after warming (hollow circles and dash lines in blue).

The 16S and ITS rRNA gene amplicons identified 142 and 212 taxa in the 54 samples of bacterial and fungal communities, respectively. In general, the abundance and diversity of bacteria were lower than that of fungi (Fig. 2A, B). For OTU-level profiling and hierarchical clustering analysis (Additional file 1: Fig. S2), the differences caused by high temperature to bacteria were more differentiable than those to fungi. This result was also reflected in partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and β-diversity (Additional file 1: Fig. S3).

The taxonomic composition of bacteria and fungi. A The mean richness of bacterial and fungal OTUs, evaluated by the Chao1 index, was mainly shown by the gathering of control (n = 12) and warmed groups (n = 12). Statistical significance between the two groups was calculated by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, showing no significant difference. B The differences of microbial diversity between control and warmed were analyzed by Student’s t-tests (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). Bacterial (C) and fungal (D) communities of vulnerable and adaptive communities at phylum and family levels under initial (Init.), control, and repeated warmed groups. Stages from 0 to 4 represent temperature conditions in treatment at 25, 35, 25, 35, 25 °C, respectively

Both types of initial microbial communities were mainly represented by phyla Proteobacteria (Fig. 2C). Warming had no significant impact on the community structure of adaptive communities, but greatly altered the vulnerable community, whose dominant phylum turned to Firmicutes (with abundance from 17.00% to 99.38%). At the family level of bacteria, the majority of phyla Firmicutes were dominated by the family Paenibacillaceae in control groups, while dominated by the family Bacillaceae in warmed groups (Fig. 2C, Additional file 1: Fig. S4A, C; P < 0.00001). It can be inferred from the changes in the community composition of the adaptation group at the family level (Fig. 2C) that the community biomass fluctuations were primarily driven by the abundance of the bacterial family Pseudomonadaceae, whose relative biomass plummeted in vulnerable groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S4A; 82.22% vs. 0.51% in controls and treatments, respectively; P < 0.001) but increased in adaptive groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S4C; 29.25% vs. 57.53% in controls and treatments, respectively; P < 0.05) after warming. The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) cladograms showed more detailed changes and differences in community structure after repeated warming from phylum-level to OTU-level (Additional file 1: Fig. S5, S6).

Changes in microbial network and carbon metabolic capability

Warming had different effects on the complexity of the associated networks in different microbial communities. After warming disturbance, the microbial network complexity of adaptive communities decreased with lower richness and connectivity but the cohesiveness increased (0.55 vs. 0.82 cohesiveness in control and warmed samples, respectively), while the vulnerable community networks exhibited opposite characteristics (Fig. 3A and Additional file 1: Table S3). What’s more, all the relative links in the adaptive community after warming were positive links (Additional file 1: Table S3).

The cooccurrence networks and function prediction for microbial communities. A The nodes in different colors indicated individual bacterial or fungal OTU, colored according to phylum. Larger nodes indicate the OTU was relatively more abundant within that group. The lines represented significant Spearman correlations (|R|< 0.6 and P < 0.05) between OTUs. The gray and black lines indicated positive and negative correlations, respectively. B Functional characteristics of bacterial samples (n = 54) were predicted by Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxonomy (FAPROTAX). C Pairwise comparisons and significant testing (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05) for vulnerable (red bar) and adaptive (blue bar) communities

Warming disturbance had a greater impact on bacterial function than fungi. The Faprotax function prediction results for bacteria showed significant variation among the treatments for over half of the bacterial functions (Fig. 3B, P < 0.05), while the FUNGuild function prediction for fungi showed significant differences only in two functional groups between control and warmed groups (Additional file 1: Fig. S7). After the high-temperature disturbance, the bacterial functional groups like nitrogen respiration and nitrate respiration significantly decreased in vulnerable groups (Fig. 3C, P < 0.05) but showed no significant changes in adaptive groups (P > 0.05). There were some functional groups, such as dark hydrogen oxidation, nitrite respiration, and so on, with significant small increases in both two microbial communities after warming (Fig. 3C, P < 0.01).

According to the Biolog results, the utilization of carbon sources fluctuated in different microbial communities under high-temperature disturbance. The results of the corresponding ratio of heatwaves to microbial carbon metabolism activity showed that warming decreased the microbial diversity and carbon metabolic capacity of vulnerable groups (Fig. 4A, B). Warming had slightly different effects on carbon metabolic capacity in the adaptive groups, with statistically significant at stage 4 (Fig. 4A). High temperature impaired the metabolic capability of labile carbon in vulnerable groups (Fig. 4C), while enhancing such capability in adaptive communities (Fig. 4D).

The warming effect on carbon metabolic capacity. A, B The microbial carbon metabolic activity (evaluated by AWCD) and diversity (evaluated by Simpson’s diversity index) at 120 h in the Biolog experiment. Response ratio (RR) was calculated as warmed/control. C, D Carbon metabolic capacity of different types of carbon sources. The differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05), marked by black stars. E The carbon metabolic capacity of three labile carbon sources. The change in carbon metabolism was calculated as (warmed − control)/control × 100%. Error bars represent standard error (n = 3). The differences between control and warmed were analyzed by Student’s t-tests (***P < 0.01, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05), and marked by red stars. Stages from 1 to 4 represent temperature conditions in treatment at 35, 25, 35, 25 °C, respectively

The intracellular metabolite changes of microbial communities

In revealing microbial metabolism associated with microbial communities, Mantel test analysis (Fig. 5) suggested that the significant correlations between bacteria and metabolites were more than that between fungi and that the majority of correlations were positive correlations between metabolites (80.95% of all 231 correlations). To further clarify these associations, we constructed links between representative differentially abundant metabolites and microbial species described earlier. In the correlation data set of differential metabolites and microbes, only 11.57% and 5.71% of all associations with bacteria and fungi, respectively, were significant (Additional file 1: Fig. S7, P < 0.05). Of these statistically significant associations, the connection between differential metabolites and bacterial communities was stronger than that of fungal communities. The correlation heatmap and microbial relative abundance bars indicated that the relative abundance of microbial species had little effect on such correlations and that the significant relationships between microbes and metabolites were mostly concentrated in metabolites related to amino acid metabolism pathways (Additional file 1: Fig. S8).

Under high-temperature disturbance, the types of differential metabolites in vulnerable groups were far more than those in adaptive groups (Fig. 6A, stage 1 and stage 3). What’s more, the significant effects of high-temperature on the metabolic pathway were mainly concentrated on the metabolism of amino acids. High-temperature generally downregulated the amino acid metabolism in vulnerable communities, but upregulated the amino acid metabolism in adaptive communities (Fig. 6B). The differential metabolites related to carbohydrate and energy metabolism only appear during the recovery phase after high-temperature disturbance (Fig. 6A, stage 2 and stage 4).

The differential metabolites and metabolomics analysis of microbes under warmed disturbance. A Relative abundance of differential metabolites between groups. These metabolites were mainly engaged in carbohydrate, energy, amino acid, lipid, and nucleotide metabolism. The abundance of differential metabolites (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05) was standardized by Z-score. The size of the black circles represented the relative abundance of differential metabolites, which was the proportion of the substance to the total abundance of all differential metabolites in the current stage. Stages from 1 to 4 represent temperature conditions in treatment at 35, 25, 35, 25 °C, respectively. B Metabolic pathway analysis. Metabolites marked green were differential metabolites, and those indicated by arrows were those significantly different between the control and warmed groups. The number below the arrow represents the stage that the metabolite changed

Discussion

Bacterial community is less stable than fungal community under warming

The warming-induced changes in the microbial communities are different, most intuitively reflected in their impact on the structure of microbial communities. Our study verified that the fungal community structure was much more stable than the bacterial community in the face of high-temperature disturbance. In our experiment, the overall richness of fungi was higher compared to bacteria, and species-rich communities were more able to maintain their ecosystem functions and had higher resistance to fluctuating environmental conditions (Bestion et al. 2021). The changes in community structure also indicate that bacteria are more sensitive to short-term environmental temperature changes and have a faster evolutionary response (Huang et al. 2021). Although short-term warming had no significant impact on bacterial and fungal OTU richness, long-term warming can decrease the richness of bacteria and fungi (Wu et al. 2022).

The dynamic changes in community structure were partly due to the direct impact of temperature on the growth status of microorganisms, confirmed research that Proteobacteria is the main core species in colder lakes, and the population gradually decreases and eventually disappears as the temperature increases (Guo et al. 2023). For phyla Firmicutes, as the optimum growth temperature of the family Bacillaceae was higher than that of Paenibacillaceae and they can also survive in harsh environmental conditions, so family Bacillaceae dominated the phyla Firmicutes after warming (Kakagianni 2022; Patowary and Deka 2020). Other studies have shown that under competitive conditions, Bacillaceae has a more adaptive advantage than Paenibacillaceae (Sun et al. 2022). Another reason might be the indirect influence of temperature on growth conditions. Because the bacterial family Pseudomonadaceae’s optimal growth temperature is above 20 °C (Chakravarty and Anderson 2015) and they are not acid-tolerant and unable to grow below pH 4.5 (Dodd 2014), we inferred that the temperature indirectly affected the acidity of the environment, leading to changes in its relative abundance. Therefore, community structure changes to drive better adaptation of microorganisms to warming. For the adaptive microbial community, the community structure can adapt to the changes in environmental conditions in a short time, while the vulnerable community needs a longer time to recover. Although the biomass of vulnerable communities did not recover in this short-term experiment, as species with higher heat tolerance limits became more abundant, the temperature range of biological activity may be amplified or transferred (Jabiol et al. 2020; Manning et al. 2018).

Highly stable microbial communities adapt to warming by positive species correlations and adaptive functional changes

In the microbial network, the “clustering phenomenon” (low connectivity and high cohesiveness) implied that microbes altered the clustering mode to maintain microbial function under high-temperature stress (Wang et al. 2023a). What’s more, taxonomic groups tend to construct a dominant position of positive correlations to face high-pressure environments (Hernandez et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2023b). Such positive correlations between nodes in microbial co-occurrence networks could be the result of functional interdependencies among microbial communities under extreme environmental conditions (Mandakovic et al. 2018; Neilson et al. 2017). Our study also showed that microbes in adaptive communities tend to establish positive correlations to adapt to experimental warming.

The results of the bacterial functional prediction showed that warming significantly impaired nitrogen respiration and nitrate respiration in vulnerable groups, evidenced by the inhibition of the growth and activity of denitrifying communities. Our results are consistent with previous studies which found that the higher temperature ascribed to climate change might decrease the reduction of nitrate in the lakes (Jiang et al. 2023b). It has been reported that denitrifiers display a notable sensitivity to changes in temperature (Kuypers et al. 2018; Palacin-Lizarbe et al. 2018). In this study, we also observed that a significant decrease in aerobic denitrifiers Pseudomonadaceae after high temperature led to such responsive changes in nitrogen metabolism. Because of the diverse forms of nitrogen in the process of nitrogen metabolism (Gruber and Galloway 2008; Ollivier et al. 2011), nitrogen cycle-based metabolic functions are particularly vulnerable to environmental fluctuations, such as temperature, nutrient, pH and dissolved oxygen (Jiang et al. 2023a; Palacin-Lizarbe et al. 2018). The stability of microbial communities has an impact on their maintenance of ecosystem functions because highly stable microbial communities (strong resistance to warming) play a more important role in preserving the initial “functional optimal” communities and ecosystem functions (Hammill et al. 2018; Pasari et al. 2013).

Moderate warming enhances the metabolic capacity of microbial communities by stimulating fungal metabolism

Warming can affect the carbon use efficiency of microbes through changes in microbial growth and the microbial community structure (Dijkstra et al. 2015). Warming significantly weakened the microbial biomass of the vulnerable communities, resulting in the decrease of degrading enzymes, which leads to a decrease in carbon metabolism. Microbial adaptation or changes in microbial communities may lead to an increase in carbon use efficiency, offsetting the decline in microbial biomass (Allison et al. 2010). Generally, the decomposition of carbon increases in warming conditions (Hu et al. 2024). From the view of the carbon sources, molecules with higher energy availability are easier decomposed by microbes as the temperature increases (Williams and Plante 2018). The energy source of most microorganisms is labile carbon (Huang et al. 2021; Nottingham et al. 2019). Warming at suitable temperatures can increase the rapid utilization of labile carbon (Sullivan et al. 2020).

The positive correlations between bacteria and intracellular metabolites indicated a possibility that the metabolite promoted the growth of the species, or that the metabolite was generated from the species (Franzosa et al. 2019). However, most differential metabolites tended not to be linked mechanistically to most microbes, and vice versa (Franzosa et al. 2019). High temperatures reduced the metabolic capacity of vulnerable communities because the significant decrease in microbial biomass caused by excessively high temperatures has reduced microbial respiration and metabolic capacity. Nevertheless, warming increased the metabolic capacity of the adaptive community, because a 5–10 °C warming stimulated fungi metabolism (Ferreira and Chauvet 2011) and improved the nutrient utilization efficiency and organic matter turnover compacity of microbes (Fernandes et al. 2014). The structure of bacterial communities (Wan et al. 2023) and labile carbon were major factors in the changes in bacterial metabolism, while recalcitrant carbon was mainly influencing the fungi community (Wang et al. 2022). Another reason that the warming-induced effect on different communities was different in microbial metabolism and function is that the environmental temperatures of different microbial communities are inherently different, and the optimal growth temperature dominates the growth and growing states of species (García et al. 2018). Therefore, there is a certain temperature preference range for specific species within the community. The adaptive community with high species richness (Albrecht et al. 2021) and high stability would contribute more to resisting environmental changes and maintaining ecosystem functions than vulnerable communities (Pasari et al. 2013).

Conclusions

In our study, the microbial community originated from the freshwater environment in nature, and the extent to which the two types of community classifications determined in the experiment can be transferred to more complex natural communities remains a challenge. Nevertheless, our research showed that lake bacteria were more likely to be impacted by warming than fungi based on the short-term response of microbial communities under fluctuating environmental temperature. Bacterial communities were characterized by low stability under disturbance, such as biomass reduction, community composition dynamics, species diversity decreasing, and microbial function changes. Although the exact nature of the predicted interactions between bacteria and fungi has not been fully elucidated, our data revealed that microbial communities with higher adaptive ability have closer bacterial-fungal connections and more positive correlations to be interdependent to adapt to disturbances. We also found that the degree of influence of warming varies in the microbial community. For example, in China, the resilience and resistance of lake microbial communities in colder areas are far inferior to those in warmer areas when facing the same degree of heatwaves. As temperature’s indirect effects varied between microbial communities, these responses reflect the differences in the functionality and metabolic activity of microbial communities to some extent. This study provides useful information about the effect of short-term experimental warming on lake microbial communities and provides more insights to fully understand microbial adaptive mechanisms under climate warming and to illustrate how these ecosystems are at risk from climate change.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AWCD:

-

Average well color development

- FAPROTAX:

-

Functional annotation of prokaryotic taxa

- LDA:

-

Linear discriminant analysis

- LEfSe:

-

Linear discriminant analysis effect size

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PLS-DA:

-

Partial least squares discriminant analysis

- RR:

-

Response ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Adger WN (2006) Vulnerability. Global Environ Chang 16:268–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006

Albrecht J, Peters MK, Becker JN, Behler C, Classen A, Ensslin A, Ferger SW, Gebert F, Gerschlauer F, Helbig-Bonitz M, Kindeketa WJ, Kühnel A, Mayr AV, Njovu HK, Pabst H, Pommer U, Röder J, Rutten G, Schellenberger Costa D, Sierra-Cornejo N, Vogeler A, Vollstädt MGR, Dulle HI, Eardley CD, Howell KM, Keller A, Peters RS, Kakengi V, Hemp C, Zhang J, Manning P, Mueller T, Bogner C, Böhning-Gaese K, Brandl R, Hertel D, Huwe B, Kiese R, Kleyer M, Leuschner C, Kuzyakov Y, Nauss T, Tschapka M, Fischer M, Hemp A, Steffan-Dewenter I, Schleuning M (2021) Species richness is more important for ecosystem functioning than species turnover along an elevational gradient. Nat Ecol Evol 5:1582–1593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01550-9

Allison SD, Wallenstein MD, Bradford MA (2010) Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology. Nat Geosci 3:336–340. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo846

Bai E, Li SL, Xu WH, Li W, Dai WW, Jiang P (2013) A meta-analysis of experimental warming effects on terrestrial nitrogen pools and dynamics. New Phytol 199:441–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12252

Bestion E, Haegeman B, Alvarez Codesal S, Garreau A, Huet M, Barton S, Montoya JM (2021) Phytoplankton biodiversity is more important for ecosystem functioning in highly variable thermal environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118:e2019591118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2019591118

Brooks N, Adger WN (2005) Assessing and enhancing adaptive capacity. In: Lim B, Spanger-Siegfried E, Burton I, Malone E, Huq S (eds) Adaptation policy frameworks for climate change: developing strategies, policies and measures. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 165–181

Cadotte MW, Drake JA, Fukami T (2005) Constructing nature: laboratory models as necessary tools for investigating complex ecological communities. Adv Ecol Res 37:333–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2504(04)37011-x

Chakravarty S, Anderson G (2015) The genus pseudomonas. In: Goldman E, Green LH (eds) Practical handbook of microbiology. CRC Press, New York, pp 321–344

Chen T, Liu Y-X, Huang L (2022) ImageGP: An easy-to-use data visualization web server for scientific researchers. iMeta 1:e5. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.5

Chinese weather. https://lishi.tianqi.com. Accessed 20 September 2020

Cross WF, Hood JM, Benstead JP, Huryn AD, Welter JR, Gíslason GM, Ólafsson JS (2022) Nutrient enrichment intensifies the effects of warming on metabolic balance of stream ecosystems. Limnol Oceanogr Lett 7:332–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/lol2.10244

Delgado-Baquerizo M, Maestre FT, Reich PB, Jeffries TC, Gaitan JJ, Encinar D, Berdugo M, Campbell CD, Singh BK (2016) Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nat Commun 7:10541. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms10541

Dijkstra P, Salpas E, Fairbanks D, Miller EB, Hagerty SB, van Groenigen KJ, Hungate BA, Marks JC, Koch GW, Schwartz E (2015) High carbon use efficiency in soil microbial communities is related to balanced growth, not storage compound synthesis. Soil Biol Biochem 89:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.06.021

Dodd CER (2014) Pseudomonas. In: Batt CA, Tortorello ML (eds) Encyclopedia of food microbiology, 2nd edn. Academic Press, Oxford, pp 244–247

Dudgeon D, Arthington AH, Gessner MO, Kawabata Z-I, Knowler DJ, Lévêque C, Naiman RJ, Prieur-Richard A-H, Soto D, Stiassny MLJ, Sullivan CA (2006) Freshwater biodiversity: Importance, threats, status and conservation challenges. Biol Rev 81:163–182. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006950

Fernandes I, Seena S, Pascoal C, Cássio F (2014) Elevated temperature may intensify the positive effects of nutrients on microbial decomposition in streams. Freshwater Biol 59:2390–2399. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12445

Ferreira V, Chauvet E (2011) Synergistic effects of water temperature and dissolved nutrients on litter decomposition and associated fungi. Global Change Biol 17:551–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02185.x

Franzosa EA, Sirota-Madi A, Avila-Pacheco J, Fornelos N, Haiser HJ, Reinker S, Vatanen T, Hall AB, Mallick H, McIver LJ, Sauk JS, Wilson RG, Stevens BW, Scott JM, Pierce K, Deik AA, Bullock K, Imhann F, Porter JA, Zhernakova A, Fu J, Weersma RK, Wijmenga C, Clish CB, Vlamakis H, Huttenhower C, Xavier RJ (2019) Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Microbiol 4:293–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0306-4

Fuhrman JA (2009) Microbial community structure and its functional implications. Nature 459:193–199. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08058

Funguild database. http://www.funguild.org. Accessed 20 February 2022

García FC, Bestion E, Warfield R, Yvon-Durocher G (2018) Changes in temperature alter the relationship between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:10989–10994. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805518115

Gillooly JF, Brown JH, West GB, Savage VM, Charnov EL (2001) Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate. Science 293:2248–2251. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1061967

Gilpin ME, Carpenter MP, Pomerantz MJ (1986) The assembly of a laboratory community: multispecies competition in drosophila. In: Diamond J, Case TJ (eds) Community ecology. Harper and Row, New York, pp 23–40

Graham EB, Knelman JE, Schindlbacher A, Siciliano S, Breulmann M, Yannarell A, Beman JM, Abell G, Philippot L, Prosser J, Foulquier A, Yuste JC, Glanville HC, Jones DL, Angel R, Salminen J, Newton RJ, Bürgmann H, Ingram LJ, Hamer U, Siljanen HM, Peltoniemi K, Potthast K, Bañeras L, Hartmann M, Banerjee S, Yu RQ, Nogaro G, Richter A, Koranda M, Castle SC, Goberna M, Song B, Chatterjee A, Nunes OC, Lopes AR, Cao Y, Kaisermann A, Hallin S, Strickland MS, Garcia-Pausas J, Barba J, Kang H, Isobe K, Papaspyrou S, Pastorelli R, Lagomarsino A, Lindström ES, Basiliko N, Nemergut DR (2016) Microbes as engines of ecosystem function: when does community structure enhance predictions of ecosystem processes? Front Microbiol 7:214. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00214

Gruber N, Galloway JN (2008) An earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 451:293–296. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06592

Guo X, Feng J, Shi Z, Zhou X, Yuan M, Tao X, Hale L, Yuan T, Wang J, Qin Y, Zhou A, Fu Y, Wu L, He Z, Van Nostrand JD, Ning D, Liu X, Luo Y, Tiedje JM, Yang Y, Zhou J (2018) Climate warming leads to divergent succession of grassland microbial communities. Nat Clim Change 8:813–818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0254-2

Guo X, Zhou X, Hale L, Yuan MM, Ning D, Feng J, Shi ZJ, Li Z, Feng B, Gao Q, Wu L, Shi W, Zhou A, Fu Y, Wu L, He Z, Van Nostrand JD, Qiu G, Liu X-d, Luo Y, Tiedje JM, Yang Y, Zhou J (2019) Climate warming accelerates temporal scaling of grassland soil microbial biodiversity. Nat Ecol Evol 3:612–619. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0848-8

Guo Y, Gu S, Wu K, Tanentzap AJ, Yu J, Liu X, Li Q, He P, Qiu D, Deng Y, Wang P, Wu Z, Zhou Q (2023) Temperature-mediated microbial carbon utilization in China’s lakes. Global Change Biol 29:5044–5061. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16840

Haase P, Bowler DE, Baker NJ, Bonada N, Domisch S, Garcia Marquez JR, Heino J, Hering D, Jähnig SC, Schmidt-Kloiber A, Stubbington R, Altermatt F, Álvarez-Cabria M, Amatulli G, Angeler DG, Archambaud-Suard G, Jorrín IA, Aspin T, Azpiroz I, Bañares I, Ortiz JB, Bodin CL, Bonacina L, Bottarin R, Cañedo-Argüelles M, Csabai Z, Datry T, de Eyto E, Dohet A, Dörflinger G, Drohan E, Eikland KA, England J, Eriksen TE, Evtimova V, Feio MJ, Ferréol M, Floury M, Forcellini M, Forio MAE, Fornaroli R, Friberg N, Fruget J-F, Georgieva G, Goethals P, Graça MAS, Graf W, House A, Huttunen K-L, Jensen TC, Johnson RK, Jones JI, Kiesel J, Kuglerová L, Larrañaga A, Leitner P, L’Hoste L, Lizée M-H, Lorenz AW, Maire A, Arnaiz JAM, McKie BG, Millán A, Monteith D, Muotka T, Murphy JF, Ozolins D, Paavola R, Paril P, Peñas FJ, Pilotto F, Polášek M, Rasmussen JJ, Rubio M, Sánchez-Fernández D, Sandin L, Schäfer RB, Scotti A, Shen LQ, Skuja A, Stoll S, Straka M, Timm H, Tyufekchieva VG, Tziortzis I, Uzunov Y, van der Lee GH, Vannevel R, Varadinova E, Várbíró G, Velle G, Verdonschot PFM, Verdonschot RCM, Vidinova Y, Wiberg-Larsen P, Welti EAR (2023) The recovery of european freshwater biodiversity has come to a halt. Nature 620:582–588. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06400-1

Hagerty SB, van Groenigen KJ, Allison SD, Hungate BA, Schwartz E, Koch GW, Kolka RK, Dijkstra P (2014) Accelerated microbial turnover but constant growth efficiency with warming in soil. Nat Clim Change 4:903–906. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2361

Hammill E, Hawkins CP, Greig HS, Kratina P, Shurin JB, Atwood TB (2018) Landscape heterogeneity strengthens the relationship between β-diversity and ecosystem function. Ecology 99:2467–2475. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2492

Hernandez DJ, David AS, Menges ES, Searcy CA, Afkhami ME (2021) Environmental stress destabilizes microbial networks. ISME J 15:1722–1734. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-00882-x

Hu A, Jang K-S, Tanentzap AJ, Zhao W, Lennon JT, Liu J, Li M, Stegen J, Choi M, Lu Y, Feng X, Wang J (2024) Thermal responses of dissolved organic matter under global change. Nat Commun 15:576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-44813-2

Huang R, Crowther TW, Sui Y, Sun B, Liang Y (2021) High stability and metabolic capacity of bacterial community promote the rapid reduction of easily decomposing carbon in soil. Commun Biol 4:1376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02907-3

Jabiol J, Gossiaux A, Lecerf A, Rota T, Guérold F, Danger M, Poupin P, Gilbert F, Chauvet E (2020) Variable temperature effects between heterotrophic stream processes and organisms. Freshwater Biol 65:1543–1554. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.13520

Jessup CM, Kassen R, Forde SE, Kerr B, Buckling A, Rainey PB, Bohannan BJM (2004) Big questions, small worlds: microbial model systems in ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 19:189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.01.008

Jiang X, Liu C, Cai J, Hu Y, Shao K, Tang X, Gong Y, Yao X, Xu Q, Gao G (2023a) Relationships between environmental factors and N-cycling microbes reveal the indirect effect of further eutrophication on denitrification and dnra in shallow lakes. Water Res 245:120572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.120572

Jiang X, Liu C, Hu Y, Shao K, Tang X, Zhang L, Gao G, Qin B (2023b) Climate-induced salinization may lead to increased lake nitrogen retention. Water Res 228:119354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.119354

Kakagianni MN (2022) Spoilage organisms: geobacillus stearothermophilus. In: McSweeney PLH, McNamara JP (eds) Encyclopedia of dairy sciences, 3rd edn. Academic Press, Oxford, pp 384–393

Kuypers MMM, Marchant HK, Kartal B (2018) The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat Rev Microbiol 16:263–276. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2018.9

Lawton JH (1998) Ecological experiments with model systems: the ecotron facility in context. In: Resetarits WJ, Bernardo J (eds) Experimental ecology: issues and perspectives. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 170–182

Lay C-Y, Mykytczuk N, Yergeau E, Lamarche-Gagnon G, Greer C, Whyte L (2013) Defining the functional potential and active community members of a sediment microbial community in a high-arctic hypersaline subzero spring. Appl Environ Microb 79:3637–3648. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00153-13

Louca S, Parfrey LW, Doebeli M (2016) Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 353:1272–1277. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf4507

Lü W, Ren H, Ding W, Li H, Yao X, Jiang X, Qadeer A (2022) Biotic and abiotic controls on sediment carbon dioxide and methane fluxes under short-term experimental warming. Water Res 226:119312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2022.119312

Mandakovic D, Rojas C, Maldonado J, Latorre M, Travisany D, Delage E, Bihouée A, Jean G, Díaz FP, Fernández-Gómez B, Cabrera P, Gaete A, Latorre C, Gutiérrez RA, Maass A, Cambiazo V, Navarrete SA, Eveillard D, González M (2018) Structure and co-occurrence patterns in microbial communities under acute environmental stress reveal ecological factors fostering resilience. Sci Rep 8:5875. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23931-0

Manning DWP, Rosemond AD, Gulis V, Benstead JP, Kominoski JS (2018) Nutrients and temperature additively increase stream microbial respiration. Global Change Biol 24:e233–e247. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13906

Metaboanalyst. https://www.metaboanalyst.ca. Accessed 2 August 2021

Meyer-Cifuentes IE, Werner J, Jehmlich N, Will SE, Neumann-Schaal M, Ozturk B (2020) Synergistic biodegradation of aromatic-aliphatic copolyester plastic by a marine microbial consortium. Nat Commun 11:5790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19583-2

Neilson J, Califf K, Cardona C, Copeland A, Treuren W, Josephson K, Knight R, Jack G, Quade J, Caporaso J, Maier R (2017) Significant impacts of increasing aridity on the arid soil microbiome. mSystems 2:e00195-e216. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00195-16

Nottingham AT, Whitaker J, Ostle NJ, Bardgett RD, McNamara NP, Fierer N, Salinas N, Ccahuana AJQ, Turner BL, Meir P (2019) Microbial responses to warming enhance soil carbon loss following translocation across a tropical forest elevation gradient. Ecol Lett 22:1889–1899. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13379

Nottingham AT, Scott JJ, Saltonstall K, Broders K, Montero-Sanchez M, Püspök J, Bååth E, Meir P (2022) Microbial diversity declines in warmed tropical soil and respiration rise exceed predictions as communities adapt. Nat Microbio 7:1650–1660. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-022-01200-1

Ollivier J, Töwe S, Bannert A, Hai B, Kastl E-M, Meyer A, Su MX, Kleineidam K, Schloter M (2011) Nitrogen turnover in soil and global change. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 78:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01165.x

Omicstudio. https://www.omicstudio.cn. Accessed 23 April 2023

O’Reilly CM, Sharma S, Gray DK, Hampton SE, Read JS, Rowley RJ, Schneider P, Lenters JD, McIntyre PB, Kraemer BM, Weyhenmeyer GA, Straile D, Dong B, Adrian R, Allan MG, Anneville O, Arvola L, Austin J, Bailey JL, Baron JS, Brookes JD, de Eyto E, Dokulil MT, Hamilton DP, Havens K, Hetherington AL, Higgins SN, Hook S, Izmest’eva LR, Joehnk KD, Kangur K, Kasprzak P, Kumagai M, Kuusisto E, Leshkevich G, Livingstone DM, MacIntyre S, May L, Melack JM, Mueller-Navarra DC, Naumenko M, Noges P, Noges T, North RP, Plisnier P-D, Rigosi A, Rimmer A, Rogora M, Rudstam LG, Rusak JA, Salmaso N, Samal NR, Schindler DE, Schladow SG, Schmid M, Schmidt SR, Silow E, Soylu ME, Teubner K, Verburg P, Voutilainen A, Watkinson A, Williamson CE, Zhang G (2015) Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophys Res Lett 42:10773–10781. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL066235

Palacin-Lizarbe C, Camarero L, Catalan J (2018) Denitrification temperature dependence in remote, cold, and N-poor lake sediments. Water Resour Res 54:1161–1173. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017WR021680

Pasari JR, Levi T, Zavaleta ES, Tilman D (2013) Several scales of biodiversity affect ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:10219–10222. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1220333110

Pascual-Garcia A, Bell T (2020) Community-level signatures of ecological succession in natural bacterial communities. Nat Commun 11:2386. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16011-3

Patowary R, Deka H (2020) Paenibacillus. In: Amaresan N, Senthil Kumar M, Annapurna K, Kumar K, Sankaranarayanan A (eds) Beneficial microbes in agro-ecology. Academic Press, pp 339–361

Qu Q, Xu J, Kang W, Feng R, Hu X (2023) Ensemble learning model identifies adaptation classification and turning points of river microbial communities in response to heatwaves. Global Change Biol 29:6988–7000. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16985

Reasoner DJ, Geldreich EE (1985) A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl Environ Microb 49:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.49.1.1-7.1985

Ren L, He D, Chen Z, Jeppesen E, Lauridsen TL, Søndergaard M, Liu Z, Wu QL (2017) Warming and nutrient enrichment in combination increase stochasticity and beta diversity of bacterioplankton assemblages across freshwater mesocosms. ISME J 11:613–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.159

Renes SE, Sjostedt J, Fetzer I, Langenheder S (2020) Disturbance history can increase functional stability in the face of both repeated disturbances of the same type and novel disturbances. Sci Rep 10:11333. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68104-0

Sarmento H, Morana C, Gasol JM (2016) Bacterioplankton niche partitioning in the use of phytoplankton-derived dissolved organic carbon: quantity is more important than quality. ISME J 10:2582–2592. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.66

Shilky, Patra S, Harshvardhan A, Kumar A, Saikia P (2023) Role of microbes in controlling the geochemical composition of aquatic ecosystems. In: Madhav S, Singh VB, Kumar M, Singh S (eds) Hydrogeochemistry of aquatic ecosystems. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., pp 265–281

Sullivan PF, Stokes MC, McMillan CK, Weintraub MN (2020) Labile carbon limits late winter microbial activity near Arctic treeline. Nat Commun 11:4024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17790-5

Sun X, Xu Z, Xie J, Hesselberg-Thomsen V, Tan T, Zheng D, Strube ML, Dragoš A, Shen Q, Zhang R, Kovács ÁT (2022) Bacillus velezensis stimulates resident rhizosphere pseudomonas stutzeri for plant health through metabolic interactions. ISME J 16:774–787. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-01125-3

Tao F, Huang Y, Hungate BA, Manzoni S, Frey SD, Schmidt MWI, Reichstein M, Carvalhais N, Ciais P, Jiang L, Lehmann J, Wang Y-P, Houlton BZ, Ahrens B, Mishra U, Hugelius G, Hocking TD, Lu X, Shi Z, Viatkin K, Vargas R, Yigini Y, Omuto C, Malik AA, Peralta G, Cuevas-Corona R, Di Paolo LE, Luotto I, Liao C, Liang Y-S, Saynes VS, Huang X, Luo Y (2023) Microbial carbon use efficiency promotes global soil carbon storage. Nature 618:981–985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06042-3

Thébault E, Fontaine C (2010) Stability of ecological communities and the architecture of mutualistic and trophic networks. Science 329:853–856. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188321

Valenzuela JJ, Garcia L, de Lomana A, Lee A, Armbrust EV, Orellana MV, Baliga NS (2018) Ocean acidification conditions increase resilience of marine diatoms. Nat Commun 9:2328. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04742-3

Walker TWN, Kaiser C, Strasser F, Herbold CW, Leblans NIW, Woebken D, Janssens IA, Sigurdsson BD, Richter A (2018) Microbial temperature sensitivity and biomass change explain soil carbon loss with warming. Nat Clim Change 8:885–889. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0259-x

Wan P, Zhang F, Zhang K, Li Y, Qin R, Yang J, Fang C, Kuzyakov Y, Li S, Li F-M (2023) Soil warming decreases carbon availability and reduces metabolic functions of bacteria. Catena 223:106913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.106913

Wang H, Li J, Chen H, Liu H, Nie M (2022) Enzymic moderations of bacterial and fungal communities on short- and long-term warming impacts on soil organic carbon. Sci Total Environ 804:150197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150197

Wang S, Wang R, Vyzmal J, Hu Y, Li W, Wang J, Lei Y, Zhai X, Zhao X, Li J, Cui L (2023a) Shifts of active microbial community structure and functions in constructed wetlands responded to continuous decreasing temperature in winter. Chemosphere 335:139080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139080

Wang Z, Hu X, Qu Q, Hao W, Deng P, Kang W, Feng R (2023b) Dual regulatory effects of microplastics and heat waves on river microbial carbon metabolism. J Hazard Mater 441:129879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129879

Williams EK, Plante AF (2018) A bioenergetic framework for assessing soil organic matter persistence. Front Earth Sci 6:143. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2018.00143

Winder JC, Braga LPP, Kuhn MA, Thompson LM, Olefeldt D, Tanentzap AJ (2023) Climate warming has direct and indirect effects on microbes associated with carbon cycling in northern lakes. Global Change Biol 29:3039–3053. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16655

Woolway RI, Maberly SC (2020) Climate velocity in inland standing waters. Nat Clim Change 10:1124–1129. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0889-7

Wu L, Ning D, Zhang B, Li Y, Zhang P, Shan X, Zhang Q, Brown MR, Li Z, Van Nostrand JD, Ling F, Xiao N, Zhang Y, Vierheilig J, Wells GF, Yang Y, Deng Y, Tu Q, Wang A, Global Water Microbiome C, Zhang T, He Z, Keller J, Nielsen PH, Alvarez PJJ, Criddle CS, Wagner M, Tiedje JM, He Q, Curtis TP, Stahl DA, Alvarez-Cohen L, Rittmann BE, Wen X, Zhou J (2019) Global diversity and biogeography of bacterial communities in wastewater treatment plants. Nat Microbiol 4:1183–1195. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0426-5

Wu L, Zhang Y, Guo X, Ning D, Zhou X, Feng J, Yuan MM, Liu S, Guo J, Gao Z, Ma J, Kuang J, Jian S, Han S, Yang Z, Ouyang Y, Fu Y, Xiao N, Liu X, Wu L, Zhou A, Yang Y, Tiedje JM, Zhou J (2022) Reduction of microbial diversity in grassland soil is driven by long-term climate warming. Nat Microbiol 7:1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-022-01147-3

Yang J, Jiang H, Dong H, Liu Y (2019) A comprehensive census of lake microbial diversity on a global scale. Sci China Life Sci 62:1320–1331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-018-9525-9

Yang J, Yu Q, Su W, Wang S, Wang X, Han Q, Qu J, Li H (2023) Metagenomics reveals elevated temperature causes nitrogen accumulation mainly by inhibiting nitrate reduction process in polluted water. Sci Total Environ 882:163631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163631

Yuan MM, Guo X, Wu L, Zhang Y, Xiao N, Ning D, Shi Z, Zhou X, Wu L, Yang Y, Tiedje JM, Zhou J (2021) Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat Clim Change 11:343–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-00989-9

Zhang Q, Qin W, Feng J, Li X, Zhang Z, He J-S, Schimel JP, Zhu B (2023a) Whole-soil-profile warming does not change microbial carbon use efficiency in surface and deep soils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120:e2302190120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2302190120

Zhang Y, Li J-T, Xu X, Chen H-Y, Zhu T, Xu J-J, Xu X-N, Li J-Q, Liang C, Li B, Fang C-M, Nie M (2023b) Temperature fluctuation promotes the thermal adaptation of soil microbial respiration. Nat Ecol Evol 7:205–213. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01944-3

Zorz JK, Sharp C, Kleiner M, Gordon PMK, Pon RT, Dong X, Strous M (2019) A shared core microbiome in soda lakes separated by large distances. Nat Commun 10:4230. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12195-5

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of People’s Republic of China as a key technology research and development program project (Grant number 2023YFC3709001), the Ministry of Education of People's Republic of China as a discipline innovation and intelligence introduction project (Grant number B17025), and the Tianjin Science and Technology Bureau as a key science and technology supporting project (Grant number S19ZC60133).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaotong Wu: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Qixing Zhou: Conceptualization, Resources, Project administration, Supervision, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Hui Zeng: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization. Xiangang Hu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed and approved the manuscript for publication in Ecological Processes.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1.

Information on the 8 lakes. Table S2. The components in R3A medium (in mg L-1 of double distilled water). Table S3. Microbial networks characteristics for each group. Fig. S1. The cell number changes in the microcosm experiment. Fig. S2. OTU profiling. Fig. S3. Analysis of differences between groups. Fig. S4. Experimental warming regulated the abundance of microbial OTUs on a family-level. Fig. S5. The distribution of the bacterial lineages showed essential bacteria in the classification level from phylum to OTU. Fig. S6. The distribution of the fungal lineages associated with vulnerable and adaptive communities. Fig. S7. FUNGuild function prediction on fungal functional group. Fig. S8. Spearman correlations between differentially abundant microbial taxa and differential metabolites.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Zhou, Q., Zeng, H. et al. Lake microbiome composition determines community adaptability to warming perturbations. Ecol Process 13, 33 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-024-00516-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-024-00516-6