Abstract

Introduction

The presence of larger trees in semi-arid African savannas creates sub-habitats, which influences on herbaceous plant communities grown under their canopies differently from opened areas. Knowledge of seed banks accumulated in the soils over time beneath larger trees could facilitate the recovery of plant communities that might disappear due to sustained heavy grazing, prolonged fire, or other anthropogenic factors in semi-arid African savannas. However, the impact of larger trees on soil seed bank composition and its similarity with plant communities grown under their canopies are less understood in semi-arid African savannas. Therefore, we studied the effect of leguminous and non-leguminous tree species and their canopies on soil seed bank (SSB) composition and its similarity with understory vegetation (USV) in a semi-arid savanna of Ethiopia.

Methods

We selected 20 matured trees from 3 dominant tree species, representing one leguminous (Acacia robusta Burch) and 2 non-leguminous tree species (Ziziphus spina-Christi and Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del), found in isolation, a total of 60 trees for this study. Under each selected individual tree, the species composition of USV were recorded using 1-m2 quadrat in four directions (north, south, east, and west) under the inside and outside tree canopies during the flowering stage. Similarly, soil samples in a 1-m2 quadrat were also collected under the inside tree canopies and their corresponding outside canopies, in each individual tree, for the determination of SSB composition, using a seed emergence method. Then, the soil was thoroughly mixed after removal of all roots and plant fragments, and spread over sand in plastic pots to a depth of 20 mm. The pots were placed at random in a glasshouse, examined every 3 days, for the first 2 months, and thereafter weekly for 6 months. A total of 960 soil samples were used for the determination of SSB composition during this study.

Results

A total of 64 species were emerged from the SSB samples, of which 27 were grasses (19 annual and 8 perennial grasses), 35 annual forbs and 2 woody species. Acacia robusta had a higher seedling density in the SSB compared to other tree species, whereas Z. spina-Christi had higher species diversity in the SSB than other tree species. Moreover, seedling density and species diversity were higher under the inside canopies than outside tree canopies. The mean similarity in species composition between the SSB and USV was low. However, it was higher under the leguminous trees than non-leguminous trees, and under the inside tree canopies than outside canopies.

Conclusions

We found that mature tree species maintained a higher SSB species diversity and abundance under their canopies than the surrounding opened areas. Therefore, conservation of mature dominant tree species is of paramount importance for ecological stability and possible restoration of degraded semi-arid savannas under the changing climate and global warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The typical feature of semi-arid African savannas is the co-existence of scattered trees and shrubs with a continuous grass layers (Scholes and Archer 1997; Sankaran et al. 2004). The abundance and spatial distribution of grass species in semi-arid savannas is determined by the complex dynamic interactions between trees and grasses (Van de Koppel and Prins 1998; van Langevelde et al. 2003). However, the tree: grass balance in semi-arid African savannas is highly disturbed as a result of continuous heavy grazing (Rietkerk and van de Koppel 1997; Tessema et al. 2011), frequent fires (van Langevelde et al. 2003), and bush encroachment (Ward 2005; Angassa and Oba 2010), leading to land and vegetation degradation (Dodd 1994; Vetter 2005). Therefore, the lack of perennial grasses (Zimmermann et al. 2010; Tessema et al. 2012) that serve as a source of feeds is a serious challenge to both wild and domestic herbivores, thus threatening the livelihoods of millions of people in semi-arid savannas worldwide (Vetter 2005; Kassahun et al. 2009).

According to previous studies (e.g., Belsky 1994; Belsky et al. 1989; Weltzin and Coughenour 1990; Ludwig et al. 2001), grass species diversity is higher under tree canopies than open areas due to the increased soil nutrients and shade in semi-arid African savannas. A higher grass diversity and productivity beneath tree canopies than outside canopies in semi-arid savannas might be also attributed as a result of increased soil moisture availability due to the higher hydraulic lift effect of the roots of larger trees (Ludwig et al. 2001; 2003). In addition, leguminous woody trees could accumulate higher soil nutrients under their canopies than non-leguminous trees in semi-arid African savannas that could facilitate higher species diversity (Belsky et al. 1993; Scholes and Archer 1997).Larger trees usually modify the micro-climate beneath tree canopies in semi-arid African savannas, where there are extreme gradients of moisture and soil nutrients, leading to a complex local interaction between understory vegetation and soils (Wilson 1990; Mitchell et al. 2012). Because large trees could create micro-habitats conducive to understory plant communities compared to outside tree canopies (Jetsch et al. 1996; Bertiller 1998).

Despite their huge importance, larger trees are being cut for charcoal, firewood, and timber production in semi-arid eastern and southern African savannas (Caro et al. 2005; Treydte et al. 2007; Tessema et al. 2011), leading to the loss of biological diversity and ecological stability (Mekuria et al. 2007; Treydte et al. 2007) that could affect the restoration potentials of degraded semi-arid African savannas (Kassahun et al. 2009; Tessema et al. 2012). Knowledge of long-lived seeds in the soils accumulated over time beneath larger trees in semi-arid African savannas could facilitate the re-colonization of grass species after disappearance (O’Connor and Pickett 1992), since seeds of various types of understory vegetation might survive for longer time (Scott et al. 2010). In addition, the influence of mature trees on plant communities growing under their canopies is reported to be tree species and site-specific in semi-arid African savannas (Kahi et al. 2009; Mitchell et al. 2012). However, the impacts of larger trees on soil seed bank composition and its similarity with plant communities grown under their canopies are less understood, and information is either minimal or lacking in semi-arid African savannas. Therefore, we studied the effect of leguminous and non-leguminous tree species and their canopies on soil seed bank composition and its similarity with understory vegetation in an experimental setup, and tested the following hypotheses: (i) soil seed bank composition and understory vegetation are higher under leguminous trees than non-leguminous trees, (ii) inside tree canopies amplify increased soil seed bank composition and understory vegetation than the surrounding open areas, and (iii) the similarity in species composition between the soil seed bank and understory vegetation is higher under the canopies of leguminous trees.

Methods

Description of the study area

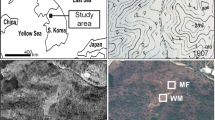

The study was conducted at Babile Elephant Sanctuary (BES: 08° 22′ 30″–09° 00′ 30′′ N; 42° 01′ 10′′–43° 05′ 50′′ E; 850–1785 meter above sea level), located in the eastern parts of Ethiopia (Fig. 1). The BES, which was established in 1970, covers about 6 982 km2 and is located 560 km southeast of Addis Ababa, which represents a semi-arid savanna ecosystems of Ethiopia (Belayneh et al. 2011; Tessema and Belay 2017). The BES was selected for this study because there are larger tree species found in isolation compared to the neighboring communal grazing lands, and it is possible to contrast the inside tree canopies with the surrounding opened areas for the composition of the soil seed bank and understory vegetation. The mean annual rainfall of BES was 702.9 mm, ranging between 452–1116.9 mm, and was highly variable among years (Tessema and Belay 2017). Its main rainy season is from July to September, with a short rainy season from March to April. The mean daily minimum and maximum temperatures are 11.9 and 27.2 °C, respectively, with a mean daily temperature of 19.6 °C (Belayneh et al. 2011).

The BES was established to protect the only surviving African elephant (Loxodonta Africana orleansi) population in the Horn of Africa (Barnes et al. 1999). The area is also known for its diverse groups of wild animals, which include crested porcupine (Hystrix cristata), Abyssinian hare (Lepus habessinicus), grivet monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops), lesser galago (Galago senegalensis), black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas), white-tailed mongoose (Ichneumia albicauda), dwarf mongoose (Helogale parvula), spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta), large-spotted genet (Genetta macullata), caracal (Lynx caracal), rock hyrax (Procavia capensis), warthogs (Phacochoerus africanus and P. aethiopicus), lesser (Tragelaphus imberbis) and greater kudus (T. strepsiceros), bush duiker (Sylvica pragrimmia), Phillip’s dik-dik (Madaqua saltiana), and Guenther’s dik-dik (Rhynchotragus guentheri) (Belayneh et al. 2011). The vegetation of BES is composed of Acacia-Commiphora woodland, semi-desert scrubland, and evergreen scrub ecosystems, dominated by A. robusta Burch., Tamirandus indica L., Oncoba spinosa Forsk, A. tortilis, Balanites aegyptiaca, and Ziziphus spina-Christi. Lantana camara, Grewia shweinfurtii, and Glycine spp. are the dominant shrub species in BES (Belayneh et al. 2011).

Selection of sampling sites

Based on visual field observation and previous vegetation studies (Belayneh et al. 2011), three dominant tree species, representing one leguminous (Acacia robusta Burch) and two non-leguminous tree species (Ziziphus spina-Christi and Balanites aegyptiaca L.), found in isolation, were selected for this study. These tree species were selected based on their abundance and distribution, as well as based on their canopy size, basal areas (DBH = cross-sectional area of the stem), and tree heights in the study site according to previous vegetation studies (Belayneh et al. 2011; Biru and Bekele 2012) and based on visual field observations prior to this study. Accordingly, 20 mature trees, from each species, were systematically selected based on their similar canopy size (≈25 m2 diameter) and tree height (≈8 m) according to previous studies (Ludwig et al. 2004; Kahi et al. 2009; Tessema and Belay 2017), without shrubs or termite mounds under or close to their canopies. Moreover, exclosures were erected around all the experimental trees and adjacent open areas before the start of the main rain, beginning of June 2012 up to October 2012, the end of the study, to keep off wild and domestic herbivores from grazing. In total, 60 trees (3 tree species × 20 trees) were selected for this study. The height of each individual trees from each tree species was estimated by walking away from the tree bending forward and looking through two legs back to the tree by stopping as reached at a point where it is possible to see the top of the tree (at 45o) and measure the distance along the ground of the tree. It is assumed that this distance is equivalent to the height of the tree (Savadogo and Elfving, 2007). The canopy diameter (CD) of trees was measured by using measuring tape on ground level throughout the canopy length in two dimensions, at right angle to each other. According to Savadogo and Elfving (2007), the vertical projected canopy area of each tree species was calculated using the following formula: CA = (CD1 × CD2) × π/4, where CD1 and CD2 are the two canopy diameters in two dimensions at right angle to each other’s.

Sampling of understory vegetation composition

To compare the soil seed bank composition with the understory vegetation, the herbaceous species, as well as seedlings and saplings of woody species under the inside tree canopies and outside their canopies (≥8 m) of each tree species were assessed. Under each selected individual tree, the species diversity and abundance of understory vegetation were recorded and identified using 1-m2 quadrat in four directions (north, south, east, and west) under the inside and outside canopy (Fig. 2) during the flowering stage of most herbaceous species in September 2012. Four quadrats were used under the inside and outside canopy of each individual tree, totaling 480 samples (3 tree species × 20 trees/species × 2 canopy cover × 4 directions as sample quadrats). For those plant species that were difficult to identify in the field, their local names were recorded, herbarium specimens were collected, pressed and dried properly, and transported to the herbarium at Haramaya University of Ethiopia, for further identification. The species were classified into grasses (annuals and perennials), herbaceous legumes, forbs, and woody species to determine the contribution of each functional group. Individual plants in each species were counted in each quadrat to determine relative abundance. For further details, the understory vegetation composition was described in Tessema and Belay (2017). Moreover, the list of species in the understory vegetation with their relative abundance, life forms, and functional groups in each tree species under the inside and outside tree canopies at BES of Ethiopia is presented as a Supplementary data (Appendix Table 5) of this manuscript.

Sampling design for data collection of both understory vegetation and soil seed bank composition under the inside and outside tree canopy at Babile Elephant Sanctuary, eastern Ethiopia. Understory vegetation and soil seed bank composition were recorded on a 1-m2 quadrats, and sampling plots were laid out in four directions (north, south, east, and west) within the canopy and outside the canopy of each tree

Procedures of soil seed bank study

Soil samples for the soil seed bank study were collected at the end of September 2012, during the end of the growing season, after seed production of most herbaceous species, at the same sampling site of the understory vegetation. The sampling of herbaceous species after seed production serve as an indication of viable seeds not germinated in the soil over the season. Four soil samples in a 1-m2 quadrat, at two soil depths (0–5 and 5–10 cm) were collected at the north, south, east, and west direction, under the inside tree canopies and their corresponding outside canopies, in each individual tree, yielding a total of 960 samples (3 tree species × 20 trees × 2 canopy cover × 2 soil depth × 4 directions as sample quadrats) for determination of SSB composition (Fig. 2). Sampling of soil at two soil depths was to examine the vertical distribution of seeds buried along the depth and to differentiate between transient and persistent seed banks under the inside and outside canopies of each tree species. The soil samples from the same soil depth in each sampling site were pooled and mixed to form a composite soil sample for each of the two soil depths under the inside tree canopy and outside canopies in each tree, yielding 48 composite soil samples (3 tree species × 2 canopy covers × 2 soil depths × 4 directions as sampling site). Finally, each of the 48 composite soil samples was divided into three equal parts, out of which one was randomly chosen for the SSB germination study.

The number of seedlings of different species emerging from the soil samples was used as a measure of the number of viable seeds for the species composition of SSB (Gross 1990). We used a seed emergence method instead of the actual seed identification (Gross 1990; Page et al. 2006) because it determines the relative abundance of viable seeds that can germinate by excluding the non-viable seeds (Poiani and Johanson 1988; Page et al. 2006). The soil was thoroughly mixed after removal of all roots and plant fragments, and spread over sand in plastic pots to a depth of 20 mm. Five pots (area = 0.053 m2) were used per composite soil sample per soil depth, totaling 60 pots (3 tree species × 2 canopy covers × 2 soil depths and 5 replications).The pots were placed at random in the glasshouse at Haramaya University, with no artificial light supplied. The glasshouse temperature was 19–22 °C during the day time and 10–12 °C during the night. The pots were examined every 3 days for the first 2 months, and thereafter weekly until the end of the experiment. Each pot was hand-watered regularly until saturated. Seedlings started to emerge after 1 week, and those seedlings that were readily identifiable counted, recorded, and discarded. Those difficult to identify at the seedling stage were counted, but maintained in the pots until they were identified. The soil sample incubation was done for a period of 6 months (November 2012–April 2013), since the number of emerging seedlings, particularly grasses and annual forbs declined considerably after 6 months. For plant nomenclature, we followed Cufodontis (1953–1972), Fromman and Pearson (1974), and Philips (1995).

Data analyses

The density of seeds (number of emerged seedlings), number of species (species richness), species composition and life forms (grasses, herbaceous legumes, forbs, and woody species), and number of individual plants in each species (plant abundance) were recorded both in the soil seed banks and understory vegetation. Species diversity was calculated using Shannon Wieners Diversity (H’), and Jaccard’s coefficient of similarity (Magurran 2004) was used to test for similarities in species composition of the soil seed banks between tree species and their canopy covers, as well as between soil seed banks and understory vegetation. To compare the similarity in species composition between soil seed banks and understory vegetation, ordination of sampling sites under the inside and outside canopies in each tree species was also carried out by multivariate analysis (Canoco 4.5, ter Braak 1997), using principal component analysis (PCA). First, we confirmed the length of gradient on the first ordination axis is whether linear (<3) or unimodal (>4) by detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) using the abundance data of herbaceous vegetation under the inside and outside canopies of each tree species before running a PCA analysis. To test for differences in all data recorded, a generalized linear model (GLM) was applied with tree species, canopy cover, soil depth, and their interactions, as independent factors, using SAS Software (SAS Statistical Analysis System 2009). Results are presented as means ± 95% C.I., and Tukey’s HSD test was employed to investigate significant differences between means at P ≤ 0.05. Proportional data were arcsine transformed to meet the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance.

Results

Seed density in the soil seed banks

The inside tree canopy had a higher seed density (16.3 seeds/m2) in the soil seed banks compared with the outside tree canopies (12.1 seeds/m2) under each tree species (Table 1). There were also tree species-specific differences, as the number of emerged seedlings under A. robusta was higher than those under B. aegyptiaca, and Z. spina-Christi. As expected, the upper soil layer had more number of emerged seeds (16.6 seeds/m2) compared with the deeper soil layer (11.8 seeds/m2). More seeds emerged under the inside canopies of A. robusta than under the canopies of other tree species (interaction term of tree species × canopy cover; Table 1).

Species richness and composition in the soil seed banks

Of the 64 species emerged from the soil seed banks samples, 27 were grasses (19 annual and 8 perennial grasses), 35 annual forbs, and 2 woody species (Appendix Table 4). The number of species germinated from the soil seed bank samples under Z. spina-Christi was higher (48 species) than other tree species, whereas the number of species germinated from the SSB samples under A. robusta and B. aegyptiaca was similar (38 and 39 species, respectively). The PCA ordination result showed a clear separation of the sampling sites for the species composition of soil seed banks, as the species composition of the soil seed banks under the inside canopy are separately clustered from the outside canopies under each tree species (Fig. 3). The first and second axes explained together 76% of the total variation extracted by PCA.

Ordination diagram of the sampling sites for the soil seed bank composition under the inside and outside canopies of three tree species by principal component analysis (PCA) in Babile Elephant Sanctuary of eastern Ethiopia. ARIC Acacia robusta inside canopy, AROC Acacia robusta outside canopy, BAIC Balanites aegyptiaca inside canopy, BAOC Balanites aegyptiaca outside canopy, ZSIC Ziziphus spina-Christi inside canopy, ZSOC Ziziphus spina-Christi outside canopy

The average number of emerged species (species richness) in the soil seed banks was higher under Z. spina-Christi tree species (11.9 species/m2) than other tree species (Table 1). More species emerged from the inside canopies of trees compared with outside tree canopies, with a mean of 11.6 and 8.8 species/m2, respectively. Similarly, the upper soil layer had a higher number of emerged species (12.5 species/m2) than the deeper soil layer (7.9 species/m2). Ziziphus spina-Christi had a higher Shannon Wiener species diversity in the SSB than A. robusta and B. aegyptiaca (Table 1). A higher Shannon Wieners species diversity values were recorded under the inside canopies compared with the outside canopy of trees.

Life forms in the soil seed banks

The number of emerged seedlings for annual grass, annual forbs, and woody species were higher (P < 0.05) under Z. spina-Christi than other tree species, whereas tree species had no significant effect (P > 0.05) on number of germinated seeds of perennial grasses from the soil seed bank samples (Table 2). Similarly, the number of annual and perennial grass seedlings emerged from the soil seed banks were not affected (P > 0.05) by the canopy cover of tree species, whereas the inside canopy had a higher number of seeds of annual forbs and woody species emerged from the soil seed banks. The upper soil layer produced more emerged seedlings of annual grasses, perennial grasses, annual forbs, and woody species compared with the deeper soil layer (Table 2).

Similarity between soil seed bank composition and understory vegetation

The total number of germinated species in the soil seed banks was lower (64 species) than the total number of species recoded in the understory vegetation (87 species; Appendix Table 5). The total number of annual and perennial grass species emerged from the soil seed banks was lower than the total number of grass species recorded in the understory vegetation. In a similar fashion, the total number of annual forbs and woody species recorded from the soil seed banks were lower than the understory vegetation.

The mean similarity in species composition between the understory vegetation samples was relatively high at 0.560 (Table 3), and ranged from 0.435 (between samples collected under the inside canopy of Z. spina-Christi and outside canopy of A. robusta) to 0.740 (between samples collected under the outside canopy of Z. spina-Christi and inside canopy of Z. spina-Christi). However, the mean similarity in species composition between the soil seed bank samples was relatively lower at 0.44, and ranged from 0.359 (between samples collected under the outside canopy of Z. spina-Christi and outside canopy of B. aegyptiaca) to 0.563 (between samples collected under the inside canopy of Z. spina-Christi and inside A. robusta). The mean similarity in species composition between the soil seed banks and understory vegetation was low (0.302; Table 3), but this was, as predicted, higher under the leguminous tree species (0.306) than non-leguminous tree species (0.295), and under the inside tree canopies (0.314) than outside canopies (0.291).

The PCA ordination separated the soil seed bank and understory vegetation composition along the first ordination axis (Fig. 4). Moreover, the PCA ordination result showed that the soil seed bank sampling sites are already separated on the first two axes, distinguishing both the inside and outside canopies under each tree species. Indeed, the soil seed bank samples were clustered together, and the understory vegetation samples were more heterogeneous, clustered in two separate groups (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Effect of tree species and canopy cover on soil seed bank composition

The number of emerged seeds (seed density) under A. robusta was higher than those under B. aegyptiaca and Z. spina-Christi in the present study. Moreover, the inside tree canopies had a higher seed density than the outside tree canopies in the soil seed banks under each tree species, as expected in our hypothesis. A higher seed density in the soil seed banks under the inside tree canopies might be due to the availability of seeds in the nests formed by birds within tree branches. Moreover, higher seeds of understory vegetation might be accumulated by domestic animals when sheltered beneath tree canopies during the sun. In addition, seeds of understory vegetation could be washed by flood during torrential rainfall from areas outside tree canopies and accumulated beneath tree canopies in semi-arid savannas (Table 5).

According to Kahi et al. (2009), tree canopies promote the growth and establishment of understory plant communities from seeds blown by wind from the outside tree canopies. Moreover, persistent soil seed banks under tree canopies can be formed when matured seeds are retained in the soil due to delayed release of seeds, which is a typical feature of semi-arid tropical environments (Tapias et al. 2001; Goubitz et al. 2004). Because delayed seed release might be important adaptation strategies of plant communities to a high intensity of disturbance in semi-arid tropical environments since it might destroy the understory vegetation. Thus, restoration of understory vegetation should rely on soil seed banks under the canopies of tree species accumulated over time. According to Keeley and Zedler (1998), delayed seed release is common among tree species growing in semi-arid savannas, particularly, in Australia and Africa, which are prone to frequent fires. Hence, considerable variation in the level of delayed release of seeds could exist among understory vegetation in semi-arid African savannas that might contribute to the composition of soil seed banks inside tree canopies than outside tree canopies.

In our study, annual forb species were found under the canopies of tree species compared to the surrounding opened areas, indicating that they are more adapted to the shaded micro-environments compared to grass species. The difference in soil temperature and evaporation under the inside tree canopies compared to outside tree canopies could contribute to the differences in the distribution of understory vegetation (Breshears et al. 1998), leading to the higher composition and species and species diversity in the soil seed banks under tree canopies than outside tree canopies in the present study.

Similarity between the soil seed banks and understory vegetation

We found that the number of species germinated in the soil seed banks was lower than the number of species recorded in the understory vegetation in the present study. According to Tessema et al. 2012), the dissimilarity between the composition of soil seed banks and aboveground vegetation in a semi-arid savanna of Africa could be characterized by more frequent occurrence of perennial grasses and woody plants in the aboveground vegetation, which could be due to short dormancy period of perennial grasses compared to annual species. In addition, Godefroid et al. (2006) indicated that the presence or absence of tree canopy cover might be also a reason for the imbalance between the composition of understory vegetation and soil seed banks, as the composition of a soil seed banks highly depends upon the types and availability of understory vegetation in the past and at present. According to Hutchings and Booth (1996), the species composition of the soil seed banks in semi-arid tropical environment are dependent upon seed rains from adjacent seed sources, indicating the contribution of outside tree canopies.

In our study, we found that higher annual species found beneath tree canopies compared to outside tree canopies, indicating that they are more adapted to the shaded micro-environments. This might contribute to the low similarity between the soil seed banks and understory vegetation in the present study, which could be due to the low seed production potential of shade-intolerant herbaceous species beneath tree species in a semi-arid environment. Because shade intolerant species beneath trees subsequently decrease in number and/or disappeared before seed setting due to their poor competition for light and/or other resources(O’Connor and Pickett 1992), which might lead to the existence of low soil seed banks beneath tree canopies. In addition, differences in hard seeded coat, germination ability, and mortality of seeds could contribute to the low similarity between the species composition of the soil seed banks and understory vegetation in semi-arid African savannas. According to previous studies (Andrew and Mott 1983; Veenendaal et al. 1996; Tessema et al. 2016), seedling mortality is expected in most semi-arid African savannas because of insufficient and erratic rainfall distribution. For instance, the mean mortality rate of grass species from the seedling stage to adult plants was 65% in semi-arid Ethiopian savannas, indicating that the seed-to-seedling stage is the most critical transitional stage for grass survival (Tessema et al. 2016), because a minimum of 15–25-mm rainfall can trigger germination of grass species in semi-arid savannas (Veenendaal et al. 1996), since perennial grasses break their dormancy immediately after seed dispersal (Tessema et al. 2016).

According to Breshears et al. (1998), soil temperature and evaporation are important factors for the understory vegetation, as they directly affect germination and growth of herbaceous species. This might be due to the difference between tree species on the effect of micro-climate with respect to soil temperature and evaporation, which in turn influence on the germination and survival of herbaceous species because it facilitates the amount of available water to understory vegetation. Similarly, the canopy effects of tree species on micro-climate may provide a facilitation effect for germination (Martens et al. 1997), as understory vegetation is primarily dependent on the moisture available beneath tree species in semi-arid tropical environments. Belsky et al. (1993) reported that the dynamics of understory vegetation in semi-arid environments depends up on the horizontal heterogeneity of soil resources, such as, moisture and temperature, created by matured tree species. Thus, tree species in semi-arid African savannas could modify the micro-climate at patch scale under their canopies, with respect to soil moisture, temperature and evaporation, which in turn affect the germination and growth of herbaceous species understory (Carr and Krueger 2012), leading to a higher seed density and species diversity in the soil seed banks of understory vegetation that would promote increased ecosystem resilience under the changing climate and environmental degradation (Table 4).

Conclusions

Our study showed that A. robusta had a higher seedling density in the soil seed banks compared to other tree species, whereas Z. spina-Christi had higher species richness and Shannon Wiener species diversity indices in the soil seed banks than other tree species. As predicted, in our hypothesis, seedling density and species diversity were higher under the inside tree canopies than outside canopies. The mean similarity in species composition between the soil seed banks and understory vegetation was low, but this was, as predicted, higher under the leguminous trees than non-leguminous trees, and under the inside tree canopies than outside canopies. We concluded that mature tree species maintained a higher soil seed bank composition inside their canopies than the surrounding open areas. If persistent understory seed banks are more diverse and had higher seed abundance, it would suggest an improved ability to tolerate environmental disturbances and ease of recovery of degraded semi-arid savannas. Therefore, conservation of mature trees of dominant species is of paramount importance for ecological stability and possible restoration of degraded semi-arid savannas of Ethiopia under the changing climate and global warming.

References

Andrew MN, Mott JJ (1983) Annuals with transient seed banks: the population biology of indigenous Sorghum species of tropical north-west Australia. Aust J Ecol 8:265–276

Angassa A, Oba G (2010) Effects of grazing pressure, age of enclosures and seasonality on bush cover dynamics and vegetation composition in southern Ethiopia. J Arid Environ 74:111–120

Barnes RFW, Craig GC, Dublin HT, Overton G, Simons W, Thouless CR (1999) African Elephant Database 1998. IUCN/SSC African Elephant Specialist Group, Gland

Belayneh A, Bekele T, Demissew S (2011) The natural vegetation of Babile elephant sanctuary, eastern Ethiopia: implications for biodiversity conservation. Ethiop J Biol Sci 10(2):137–152

Belsky AJ (1994) Influences of trees on savanna productivity - tests of shade, nutrients and tree - grass competition. Ecology 75:922–932

Belsky AJ, Amundson RG, Duxburg JM, Riha SJ, Ali AR, Mwonga SM (1989) The effect of trees on their physical, chemical and biological environments in a semi-arid savanna in Kenya. J Appl Ecol 26:1005–1024

Belsky AJ, Amundson RG, Duxburg JM, Riha SJ, Ali AR, Mwonga SM (1993) Comparative effects of isolated trees on their under canopy environments in high and low rainfall savannas. J Appl Ecol 30:143–155

Bertiller MB (1998) Spatial patterns of the germinable soil seed bank in northern Patagonia. Seed Sci Res 8:39–45

Biru Y, Bekele D (2012) Food habits of African elephant (Loxodonta africana) in Babile elephant sanctuary, Ethiopia. Trop Ecol 58(1):43–52

Breshears DD, Nyhan JN, Heil CH, Wilcox BP (1998) Effects of woody plants on microclimate in a semi-arid woodland: soil temperature and evaporation in canopy and inter-canopy patches. Int J Plant Sci 159(6):1010–1017

Caro TM, Sungula M, Schwartz MW, Bella EM (2005) Recruitment of Pterocarpus angolensis in the wild. For Ecol Manage 219:169–175

Carr CA, Krueger WC (2012) The role of the seed bank in recovery of understory species in an Eastern Oregon Ponderosa Pine forest. North West Sci 86(3):168–178

Cufodontis G (1953-1972) Enumeratioplantarum Aethiopicum spermatophyte (sequentia), Bulletin du jardinbotanique de 1 Etat a bruxelles 30: 653-708

Dodd J (1994) Desertification and degradation in sub-Saharan Africa: the role of livestock. Bioscience 44:28–33

Fromman B, Pearson S (1974) An illustrated guide to the grass of Ethiopia. Chilalo Agricultural development unit, Asella

Godefroid S, Phartyal SS, Koedam N (2006) Depth distribution and composition of soil seed banks under different tree layers in a managed temperate forest ecosystem. Acta Oecol 29:283–292

Goubitz S, Nathan R, Roitemberg D, Shmida A, Ne’eman G (2004) Canopy seed bank structure in relation to: fire, tree size and density. Plant Ecol 173:191–201

Gross KL (1990) Comparison of methods for estimating soil seed banks. J Ecol 78: 1079–1093.

Hutchings MJ, Booth KD (1996) Studies on the feasibility of re-creating chalk-grassland vegetation on ex-arable land. The potential roles of the soil seed bank and the seed rain. J Appl Ecol l33:1171–81

Jetsch F, Mutton SJ, Dean WRJ, Rooyen NV (1996) Trees spacing and co-existence in semi-arid savannah. J Ecol 84:583–595

Kahi CH, Ngugi RK, Mureithi SM, Ng’ethe JC (2009) The canopy effects of Prosopis juliflora (Dc.) and Acacia tortilis(Hayne) trees on herbaceous plants species and soil physico-chemical properties in Njemps Flats, Kenya. Trop Subtrop Agro-Ecosystems 10:441–449

Kassahun A, Snyman HA, Smit GN (2009) Soil seed bank evaluation along a degradation gradient in arid rangelands of Somali regions, eastern Ethiopia. Agric Ecosyst Environ 129:428–436

Keeley JE, Zedler PH (1998) Evolution of life histories in Pinus. In: Richardson DM (ed) Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 219–251

Ludwig F, de Kroon H, Prins HHT et al (2001) Effects of nutrients and shade on tree–grass interactions in an East African savanna. J Veg Sci 12(4):579–588

Ludwig F, Dawson TE, de Kroon H, Berendse F, Prins HHT (2003) Hydraulic lift in Acacia tortilis trees on an East African savanna. Oecologia 34:293–300

Ludwig F, de Kroon H, Berendse F, Prins HHT (2004) The influence of savanna trees on nutrient, water and light availability and the understory vegetation. Plant Ecol 170:93–105

Magurran AE (2004) Measuring of biological diversity. Blackwell publishing, London, p 256

Martens SN, Breshears DD, Meyer CW, Barnes FJ (1997) Scales of above-ground and below-ground competition in a semi-arid woodland detected from spatial pattern. J Veg Sci 8:655–664

Mekuria W, Veldkamp E, Haile M, Nyssen J, Muys B, Gebrehiwot K (2007) Effectiveness of enclosures to restore degraded soils as a result of overgrazing in Tigray, Ethiopia. J Arid Environ 69:270–284

Mitchell R, Keith A, Potts J (2012) Overstory and understory vegetation interact to alter soil community composition and activity. Plant Soil 352:65–84

O’Connor TG, Pickett GA (1992) The influence of grazing on seed production and seed banks of some African savanna grasslands. J Appl Ecol 29:247–260

Page MJ, Baxter GS, Lisle AT (2006) Evaluating the adequacy of sampling germinable soil seed banks in semi-arid systems. J Arid Environ 64:323–341

Philips S (1995) Poaceae (Gramineae). In: Hedberg I, Edwads S (eds) Flora of Ethiopia, vol 7. The National Herbarium. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa and University of systematic botany, Uppsala University, Sweden

Poiani KA, Johnson WC (1988) Evaluation of the emergence method in estimating seed bank composition of prairie wetlands. Aquatic Botany 32: 91–97.

Rietkerk M, van de Koppel J (1997) Alternate stable states and threshold effects in semi-arid grazing systems. Oikos 79:69–76

Sankaran M, Ratnam J, Hanan NP (2004) Tree-grass coexistence in savannas revisited-insights from an examination of assumptions and mechanisms invoked in existing models. Ecol Lett 7:480–490

SAS (Statistical Analysis System) (2009) Applied statistics and the SAS programming language 2nd edition Cary. SAS, North Carolina

Savadogo P, Elfving B (2007) Prediction models for estimating available fodder of two savanna tree species (Acacia dudgeon and Balanites aegyptiaca) based on field and image analysis measures. Afr J Range Forage Sci 24:63–71

Scholes RJ, Archer SR (1997) Tree-grass interactions in savannas. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 28:517–544

Scott K, Setterfield S, Douglas M, Anderson A (2010) Seed banks confer resilience to savanna grass-layer plants during seasonal disturbance. Acta Oecol 36:202–210

Tapias R, Gil L, Fuentes-Utrilla P, Pardos JA (2001) Canopy seed banks in Mediterranean pines of southeastern Spain: a comparison between Pinus halepensis Mill., P. pinaster Ait., P. nigra Arn. and P. pinea. L. J Ecol 89:629–638

Ter Braak CJF (1997) CANOCO - a FORTRAN program for canonical community ordination by [partial] [Detrended] canonical] correspondence analysis, principal component analysis and redundancy analysis (version 3.15). Institute of Applied Computer Science, 95, Wageningen

Tessema ZK, Belay E (2017) Effect of tree species on understory vegetation, herbaceous biomass and soil nutrients in a semi-arid savanna of Ethiopia. J Arid Environ 139:76–84

Tessema ZK, de Boer WF, Baars RMT, Prins HHT (2011) Changes in vegetation structure, herbaceous biomass and soil nutrients in response to grazing in semi-arid savanna in Ethiopia. J Arid Environ 75:662–670

Tessema ZK, de Boer WF, Baars RMT, Prins HHT (2012) Influence of grazing on soil seed banks determines the restoration potential of aboveground vegetation in a semi-arid savanna of Ethiopia. Biotropica 44:211–219

Tessema ZK, de Boer WF, Prins HHT (2016) Changes in grass plant populations and temporal soil seed bank dynamics in a semi-arid African savanna: Implications for restoration. J Environ Manage 182:166–175

Treydte AC, Heitkonig IMA, Prins HHT, Ludwig F (2007) Trees improve grass quality for herbivores in African savannas. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst 8:197–205

Van de Koppel J, Prins, HHT (1998) The importance of herbivore interactions for the dynamics of African savanna woodlands: an hypothesis. J Trop Ecol 14: 565–576.

Van Langevelde F, Van de Vijver CADM, Kumar L, Van de Koppel J, de Ridder N, Van Andel J, Skidmore AK, Hearene JW, Stroosnijder L, Bond WJ, Prins HHT, Rietkerk M (2003) Effects of fire and herbivory on the stability of savanna ecosystems. Ecology 84:337–350

Veenendaal EM, Ernst WHO, Modise GS (1996) Effect of seasonal rainfall pattern on seedling emergence and establishment of grasses in a savanna in south-eastern Botswana. J Arid Environ 32:305–317

Vetter S (2005) Rangelands at equilibrium and non-equilibrium: recent developments in the debate around rangeland ecology and management. J Arid Environ 62:321–341

Ward D (2005) Do we understand the causes of bush encroachment in African savannas? Afr J Range Forage Sci 22:101–105

Weltzin JF, Coughenour MB (1990) Savanna tree influence on under canopy vegetation and soil nutrients in northwestern Kenya. J Veg Sci 1: 325–334.

Wilson JR (1990) Agroforestry and soil fertility. (1) The eleventh hypothesis: shade. (2) Root nodulation: the twelfth hypothesis. Agrofor Today 2:14–15

Zimmermann J, Higgins SI, Grimm V, Hoffmann J, Linstader A (2010) Grass rate of change in semi-arid savanna: the role of fire, competition and self-shading. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst 12:1–8

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Haramaya University, Ethiopia, for providing transport during the field work and for analyzing the soil samples. We are grateful to the management of Babile Elephant Sanctuary for allowing us to conduct our research.

Authors’ contributions

TZK initiated the idea and designed the research, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. BE conducted the field research and analyzed the data. LN assisted in the write-up of the manuscript and interpretation of the results. All authors revised the manuscript, read, and approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tessema, Z.K., Ejigu, B. & Nigatu, L. Tree species determine soil seed bank composition and its similarity with understory vegetation in a semi-arid African savanna. Ecol Process 6, 9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0075-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0075-7