Abstract

Objective

To explore the impacts of surgical mask in normal subjects on cardiopulmonary function and muscle performance under different motor load and gender differences.

Design

Randomized crossover trial.

Setting

The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, June 16th to December 30th, 2020.

Participants

Thirty-one college students (age: male 21.27 ± 1.22 years; female 21.31 ± 0.79 years) were recruited and randomly allocated in two groups.

Interventions

Group 1 first received CPET in the mask-on condition followed by 48 h of washout, and then received CPET in the mask-off condition. Group 2 first received CPET in the mask-off condition followed by 48 h of washout, then received CPET in the mask-on condition. The sEMG data were simultaneously collected.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max) from CPET, which was performed on a cycle ergometer—this is the most important parameter associated with an individual’s physical conditioning. The secondary parameters included parameters reflecting exercise tolerance and heart function (oxygen uptake, anaerobic valve, maximum oxygen pulse, heart rate reserve), parameters reflecting ventilation function (respiration reserve, ventilation volume, tidal volume, breathing frequency), parameters reflecting gas exchange (end-tidal oxygen and carbon dioxide partial pressure, oxygen equivalent, carbon dioxide equivalent, and the relationship between dead space and tidal volume) and parameters reflecting skeletal muscle function [oxygen uptake, anaerobic valve, work efficiency, and EMG parameters including root mean square (RMS)].

Results

Comparing the mask-on and mask-off condition, wearing surgical mask had some negative effects on VO2/kg (peak) and ventilation (peak) in both male and female health subjects [VO2/kg (peak): 28.65 ± 3.53 vs 33.22 ± 4.31 (P = 0.001) and 22.54 ± 3.87 vs 26.61 ± 4.03 (P < 0.001) ml/min/kg in male and female respectively; ventilation (peak): 71.59 ± 16.83 vs 82.02 ± 17.01 (P = 0.015) and 42.46 ± 10.09 vs 53.95 ± 10.33 (P < 0.001) liter in male and female respectively], although, based on self-rated scales, there was no difference in subjective feelings when comparing the mask-off and mask-on condition. Wearing surgical masks showed greater lower limb muscle activity just in male subjects [mean RMS of vastus medialis (load): 65.36 ± 15.15 vs 76.46 ± 19.04 μV, P = 0.031]. Moreover, wearing surgical masks produced a greater decrease in △tidal volume (VTpeak) during intensive exercises phase in male subjects than in female [male − 0.80 ± 0.15 vs female − 0.62 ± 0.11 l P = 0.001].

Conclusions

Wearing medical/surgical mask showed a negative impact on the ventilation function in young healthy subjects during CPET, especially in high-intensity phase. Moreover, some negative effects were found both in ventilation and lower limb muscle actives in male young subjects during mask-on condition. Future studies should focus on the subjects with cardiopulmonary diseases to explore the effect of wearing mask.

Trial registration

Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000033449).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wearing mask is an effective way to prevent respiratory diseases in daily life, especially for respiratory infectious diseases during the pandemic [1]. The efficacy of public health measures to control the transmission of severe acute respiratory diseases is not certain, thus, wearing a mask outside and inside in public might be normalized for a long time. Compared with respirators (which just recommended to use by medical, wearing surgical mask is more recommended for health people in the daily life to reduce transmissions from the wearer to the patient or contact with large infectious droplets due to its easy availability, comfort, and compliance with community requirements [2]. So, all the medical masks mentioned in this study referred to the surgical masks.

Wearing mask could reduce the risk of contracting contagious respiratory infections [3, 4], but its direct physical effect hinders gas exchange at the same time, which might affect human motor performance under mask-on conditions, and even safety under high-intensity exercise.

The relevant research is extremely limited. For example, in Sven Fikenzer’s and Davies’s studies, ventilation and cardiopulmonary exercise capacity were reduced by surgical masks in 9and 12 healthy males, respectively [5, 6]. The studies published so far have each recruited only a small number of male subjects with a relatively large age span; however, age and gender differences are important factors affecting exercise and cardiopulmonary function [7, 8]. Meanwhile, none of the published studies have addressed the effect of wearing mask on the direct motor effector (muscle performance).

In this study, we used the cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) and lower limber simultaneous surface electromyography (sEMG) to explore the impacts of surgical mask in normal subjects on cardiopulmonary function and muscle performance under different motor load and gender differences.

Methods

Trial design

The study was designed as a randomized cross-over study to explore the impacts of surgical mask in normal subjects on cardiopulmonary function and muscle performance under different motor load and gender differences, which has been registered at the China Clinical Trial Registration Center (No. ChiCTR2000033449).

Participants

Subjects were recruited from college students at Guangzhou Medical University. The inclusion criteria were: subjects between 18 and 26 years old; who could pass the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) test [9]; were physically healthy; without professional sports training experience; and were able to understand the experiment and voluntarily cooperate with the whole process of the test. The exclusion criteria were: cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases; subjects with lower limb motor dysfunction caused by other diseases; subjects who could not cooperate with the experiment; smokers and any other contraindications to CPET [10]. A total of 35 subjects were recruited through electronic posters, and travel expenses were reimbursed. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

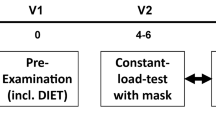

Interventions

The participants were randomly allocated into two groups using a digit table: Group 1 first received CPET in the mask-on condition followed by 48 h of washout, and then received CPET in the mask-off condition. Group 2 first received CPET in the mask-off condition followed by 48 h of washout, then received CPET in the mask-on condition. The sEMG data were simultaneously collected. The design and recruitment of the study are shown in Figs. 1 and 3A.

Surgical/medical masks

The typical and widely used disposable surgical mask with ear loops (Haozheng Weicai, Haozheng Sanitary Materials Factory, Guangzhou, China) was used in the mask-on condition during the CPET test.

Subject preparation

The laboratory temperature was set at 25 °C, and the instrument was calibrated before each test. Subject preparation including as follows: eating only a light meal at least two hours prior to the procedure, avoiding carbonated or caffeinated drinks, as well as alcohol, avoiding exercise at the day of the test, and dressing in comfortable clothes.

Spirometry testing

The participant was instructed to take a deep breath in, hold the breath for a few seconds, and then exhale as hard as he/she could into the breathing mask, which was used to test the baseline lung function in the mask-off condition (Fig. 2). The participant was asked to repeat this test at least three times to make sure the results were consistent. Forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were collected as the two main parameters to measure airflow into and out of the lungs. The FEV1/FVC ratio was calculated and used as an exclusion criterion (if less than 70%, which indicates a relatively low lung function) [11].

Cardiopulmonary exercise tests (CPETs)

The mode of cycle ergometer exercise and progressive incremental exercise (ramp protocol) were used in the CPET protocol, which consists of 2 min of the resting stage, followed by 2 min of the unloaded pedaling stage (Unloaded stage: 0 watt/min), followed by 8–12 min of incremental/ramp exercise stage [Loaded stage: increased by ramp (watt/min), and the ramp was based on the formula as follow] until the subjects reach volitional exhaustion or the test is terminated by the medical monitor (see criteria for terminating the exercise test). This CPET study protocol was referred with our previous study [12]. Then, the participant ended with 3 min of recovery stage (0 watt/min) and 3 min of observation stage (static sitting). 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) (Fig. 3B), pulse oximetry, and blood pressure were tracked to detect any abnormalities during the process (Fig. 4).

The formulas below were used for calculating the CPET performance for each participant [13]:

Criteria for terminating the exercise test

Based on the American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians Guidelines, CPET is a relatively safe procedure, especially in healthy individuals. This study followed the criteria for exercise termination before symptom limitation, as follows: chest pain suggestive of ischemia, ischemic ECG changes, complex ectopy, second- or third-degree heart block, fall in systolic pressure 20 mmHg from the highest value during the test, hypertension (250 mmHg systolic; 120 mmHg diastolic), severe desaturation: SpO2 80% when accompanied by symptoms and signs of severe hypoxemia, sudden pallor, loss of coordination, mental confusion, dizziness or faintness, and signs of respiratory failure [10].

Post-CPET assessments

The Borg category ratio scale (Borg CR-10 scale) [14] was performed after every CPET (mask-on CPET and mask-off CPET), which was used for reflecting the intensity load of performing the cycle-ergometer exercise.

Simultaneous surface electromyography (sEMG)

sEMG data were simultaneously collected using the BTS FREEEMG 1000 (BTS Bioengineering Spa, Italy) device with surface electrodes during the CPET. The electrodes were attached to the tibialis anterior (TA), lateral gastrocnemius (LG), medial gastrocnemius (MG), rectus femoris (RF), vastus medialis (VM), vastus lateralis (VL), semitendinosus (ST), and biceps femoris caput longus (BFCL) in the dominant lower limb (Fig. 3C and D).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max) from CPET, which was performed on a cycle ergometer—this is the most important parameter associated with an individual’s physical conditioning. The secondary parameters included parameters reflecting exercise tolerance and heart function (oxygen uptake, anaerobic valve, maximum oxygen pulse, heart rate reserve), parameters reflecting ventilation function (respiration reserve, ventilation volume, tidal volume, breathing frequency), parameters reflecting gas exchange (end-tidal oxygen and carbon dioxide partial pressure, oxygen equivalent, carbon dioxide equivalent, and the relationship between dead space and tidal volume) and parameters reflecting skeletal muscle function [oxygen uptake, anaerobic valve, work efficiency, and EMG parameters including root mean square (RMS)].

Sample size estimation

The number of subjects required in this cross-control trial study was calculated to ensure adequate statistical effectiveness. The value of VO2 peak was used as the main outcomes. The mean and standard deviation of five subjects in mask-on and mask-off were 1326.2 ± 123.2 and 1091.6 ± 187.6, respectively. The sample size was calculated using G-Power 3.1.9. We set effect size of 0.39 and a power of 0.95 for determining the required minimum sample size of nine.

Data collection and management

CPET data during the unloaded pedaling stage and incremental/ramp exercise stage were exported from the CPET equipment into an Excel file for statistical analysis. sEMG data were analyzed using the Smart EMG software (BTS system-provide). A 300 Hz low-pass filter and a 10 Hz high-pass filter were used by Hamming filter, and then full-wave rectification was performed, taking 100 ms as the time window for root means square (RMS) amplitude value to intercept the unload and load signals, respectively. The mean of unloading and loading were calculated for final statistical analyses.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 25, IBM Crop., Armonk, NY, USA) and figures made using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., California, USA), as described in previous studies [15, 16]. The data were expressed as means and standard deviations, and the significance level was defined as P < 0.05. The paired t-test was used for comparing differences of CPET and sEMG parameters between the mask-on condition and mask-off conditions. An independent sample t-test was used for comparing the differences between male and female subjects.

Results

The subjects in this study were recruited from college students at Guangzhou Medical University from June 16th to December 30th, 2020. Thirty-five college students were recruited in this study, and four subjects were excluded (one male subject getting cold after the first CPET and three female subjects with personal reasons after the first CPET). Thirty-one subjects completed the whole study (15 males and 16 females). None of them reported any important harms or unintended effects. The recruitment information of the study are shown in Fig. 1. There were no significant differences showed in age and body mass index (BMI) between the male group and the female group. The average age was 21.27 ± 1.22 years old in the male group and 21.31 ± 0.79 years old in the female group (P = 0.902). The average BMI was 21.33 ± 2.74 kg/m2 in the male group and 20.02 ± 2.70 kg/m2 in the female group (P = 0.190). The male group showed significantly higher forced vital capacity (FVC) and higher forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) compared with the female group. The FVC was 4.43 ± 0.38 l in the male group and 3.10 ± 0.47 l in the female group (P < 0.001). The FEV1 was 3.85 ± 0.32 l in the male group and 3.10 ± 0.47 l in the female group (P < 0.001). However, the ratio of FEV1/FVC showed no significant difference between the male group and the female group (Table 1).

Primary outcome

Table 2 showed the CPET parameters of within-group comparisons between mask-on condition and mask-off condition in male group and female group, respectively. For exercise tolerance and cardiac functions, comparing with mask-off condition, the male and female groups showed significantly decreased VO2/kg (ml/min/kg) (in unload stage, peak point, and anaerobic threshold/AT point), decreased VO2AT/VO2max (%), decreased O2/HR (ml/kg/beat) (in unload stage and peak point), decreased △VO2/△WR [ml/(min*watt)], and decreased MET (in unloading stage and peak point) in mask-on condition. At the same time, the male and female groups showed no significant differences in HR (in unload stage and at peak point) and HRR (heart rate reserve) when comparing mask-on and mask-off conditions. Also, compared with the mask-off condition, the male group showed no significant difference in SpO2 (%) in unload stage with mask-on condition, but decreased SpO2 (%) at peak point. Whereas the female group showed no significant differences in SpO2 (%) – neither in unload stage nor at peak point – between mask-on and mask-off conditions. For ventilatory function and gas exchange parameters, compared with mask-off condition, the male group and the female group showed significantly increased BR% (in unload stage and peak point) with mask-on condition. Moreover, the male group and the female group showed significantly decreased VE (in unload stage and peak point) with mask-on condition. Only the male group showed significantly increased VE/VCO2 (slope) with mask-on condition. For CPET performance, there were no significant differences in Load max (watt), exercise duration, or Borg’s scales between mask-off and mask-on conditions. There was no significant difference in exercise time for male between mask-on and mask-off, while there was no significant difference in exercise time for female between mask-on and mask-off either.

Secondary outcomes

Table 3 showed the gender differences on the CPET parameter changes (“△” was used to indicate the change between mask-on and mask-off condition). No significant differences in exercise tolerances and cardiac function as well as gas exchange were found between the male group and the female group. However, the male group showed significantly greater △VT (peak) and △BR% (peak) than the female group (△VTpeak: male − 0.80 ± 0.15 l, female − 0.62 ± 0.11 l, P = 0.001; △BR%peak: male − 1.94 ± 0.29 l, female 1.22 ± 0.22 l, P < 0.001).

Table 4 showed the within-group comparison of lower limb muscle activity (mean RMS) between mask-on and mask-off conditions in unload stage and incremental exercise stage, respectively. During the unload CPET phase, the results of sEMG showed that there were no significant differences of mean RMS between mask-on condition and mask-off condition in VM. RF, VL, TA, ST, BFCL, MG and LG. However, during the load CPET phase, the male group showed significant difference of mean RMS in VM between mask-on condition and mask-off condition.

Discussion

Principal findings

This was a randomized cross-over study exploring the impacts of surgical masks on cardiopulmonary exercise capacity (by CPET) and lower limb muscle performance (by simultaneously sEMG), which was to further investigate based on our previous study [12]. Moreover, to our knowledge, this study is the first study to simultaneously measure sEMG data during CPETs and allocated the subjects considering the gender effect.

The main findings of this study are: wearing surgical masks has some negative effects on cardiopulmonary function in both male and female health subjects, although, based on self-rated scales, there was no difference in subjective feelings when comparing the mask-off and mask-on condition. Wearing surgical masks might produce a greater decrease in ventilatory function and lower limb muscle activity during high-intensity phase of CPET in male subjects than in female subjects.

Comparison with other studies

First, wearing a surgical mask might have some negative effects on exercise tolerance and cardiac function, as reflected in the decreased VO2/kg, O2/HR, and △VO2/△WR after wearing a mask in both the male and female groups, which are related to the increased breathing resistance in the medical mask, requiring more work of the respiratory muscles and leading to higher oxygen consumption. However, Sven Fikenzer et al. [5] detected a similar cardiac output with and without mask during the incremental exercise test. This might be related to the greater age distribution and smaller subject size in Sven Fikenzer’s study (age 38.1 ± 6.2 years, nine males recruited subjects) [5]. This study also found out that no significant differences in HR and HRR in both male and female groups, which gave clue that monitoring HR alone is not the most sensitive indicator of exercise-related cardiac performance [17]. However, Lässing J et al. [18] found out that there was no significant difference in the change of blood pressure in exercise with mask on, but the peak heart rate of exercise was higher, the average cardiac output was higher, while Drivers’s study [19] indicated that the peak heart rate of wearing cloth mask for exercise test was lower, which might be related to the different test schemes. The former adopted constant power exercise test, and the latter adopted gradual treadmill exercise test, while this study adopted gradual incremental bicycle exercise test. Mehdi Ahmadian et al. [20] explored the effects of surgical mask, N95 mask and mask-off on hemodynamics and blood function in 144 healthy subjects. The results showed that there was no statistical difference in the changes of hemodynamics (systolic blood pressure, heart rate, rate pressure product) before and after exercise, regardless of gender, mask type and exercise intensity.

Second, the direct physical mechanism of wearing a medical mask is to affect ventilation and increased breathing resistance due to the 3-ply structure of non-woven material for preventing the spread of pathogenic organisms [21]. The related effect of wearing a surgical mask during different exercise conditions (unload and load) was the main aim of the study. The results showed increased breathing resistance and limitation of ventilation after wearing medical masks were found both in the unload and load phase that led to decreased VT and VE as well as increased BR% and VE/VCO2 (slope), which was likely higher during the load phase. Lässing J et al. [22] (14 males, mean age 25.7 ± 3.5 years) confirmed a significant increase in respiratory tract resistance (0.58 ± 0.16 kPa l − 1 vs. 0.32 ± 0.08 kPa l − 1; p < 0.01) in patients wearing surgical masks. p < 0.01), and VE also decreased accordingly (77.1 ± 9.3 l min − 1 vs. 82.4 ± 10.7 l min − 1; p < 0.01). Shaw K et al. [23] considered that there was no significant effect on blood oxygen saturation, tissue oxygenation index and self-perceived fatigue in healthy young subjects wearing masks during intensive exercise, and that wearing masks was safe. Susan R et al. [24] reviewed the effects of wearing different masks on cardiopulmonary function through literatures, demonstrated that although the existing data indicated the negative impact of wearing cloth or surgical masks in healthy people could be ignored, and it would not significantly affect exercise endurance, but for people with severe cardiopulmonary conditions, any increase in resistance and / or small changes in blood gas may lead to dyspnea, thereby affecting exercise ability. So, further research is needed on the safety of wearing masks for long periods of time or during exercise in such subject groups. The study also found the bigger negative effect of ventilator function in wearing a mask during the load phase in the male group than in the female group, which might be related to more exercise intensity in male subjects.

Third, the study explored not only the direct cardiopulmonary effect of wearing a medical mask, but also the close related peripheral muscle performance by lower limb sEMG during CPET. We detected a decreased mean vastus medialis muscle activity after wearing medical mask compared to no mask in the male group. The sEMG results suggest that wearing a mask might decrease motor function, especially during high-intensity exercises, due to the dominant role of vastus medialis in cycling exercises [25]. Combined with the previous changes in cardiopulmonary function, the decline of exercise tolerance in healthy people caused by surgical masks, which may be caused by the peripheral mechanism. Because masks cause ventilation restriction to the reduction of oxygen intake, resulting in the decrease of oxygen intake in peripheral muscles and exercise tolerance. Although in Sven Fikenzer’s study, there was no significant change in blood lactate value as one of the main indicators of muscle metabolism before and after wearing medical masks [5]. Moreover, female subjects in the study showed no significant differences in muscle activities between the mask-on and mask-off conditions, which might also be related to the relatively lower exercise intensity compared with male subjects.

Finally, the study also showed no significant differences in subjective fatigue feeling based on Borg’s scales assessment after the CPET test in both the male and the female groups. However, the cardiopulmonary parameter changed between the mask-on and off conditions found in the study still suggested some negative effect on wearing medical masks during exercises.

Limitations

There were three main limitations to this study. First, the blood test was not included in this study due to a previous study reporting no significant difference in peak blood lactate response when comparing the mask-on and mask-off conditions [5]. Furthermore, not immediately collecting arterial blood samples during or after CPET was also decided based on safety. The arterial blood pressure might be increased after strenuous exercise, which may cause difficulty in hemostasis. Second, our study only focused on the effect of wearing surgical masks on cardiopulmonary function because these masks are widely used and readily available in the community. Moreover, it is rarely possible to wear N95 masks for prolonged aerobic exercise due to the discomfort and community inapplicability. Third, elders and patients with cardiopulmonary diseases were not recruited in the study due to relatively little experience in this field. Further study should recruit various participants to extend the safety of application of wearing the surgical mask in daily life.

Conclusions

Wearing medical/surgical mask showed a negative impact on the ventilation function in young healthy subjects during CPET, especially in high-intensity phase. Moreover, some negative effects were found both in ventilation and lower limb muscle actives in male young subjects during mask-on condition. Future studies should focus on the subjects with cardiopulmonary diseases to explore the effect of wearing mask.

Abbreviations

- AT:

-

Anaerobic threshold per kilogram

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- BFCL:

-

Biceps femoris caput longus

- CPET:

-

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

- ECG:

-

Electrocardiography

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiatory volume in 1 second

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- HRR:

-

Heart rate reserve

- LG:

-

Lateral gastrocnemius

- kg:

-

Kilogram

- MET:

-

Metabolic equivalent

- ms:

-

Millisecond

- MG:

-

Medial gastrocnemius

- PAR-Q:

-

Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire

- RF:

-

Rectus femoris

- RMS:

-

Root mean square

- SpO2 :

-

Pulse oxyhemoglobin saturation

- ST:

-

Semitendinosus

- sEMG:

-

Surface electromyography

- TA:

-

Tibialis anterior

- VO2/kg:

-

Oxygen uptake per kilogram

- VCO2 :

-

Volume of carbon dioxide released

- VE :

-

Ventilation

- VL:

-

Vastus lateralis

- VM:

-

Vastus medialis

- VO2 max :

-

Maximal oxygen uptake

- VO2 :

-

Peak oxygen consumption

- VT:

-

Tidal volume

References

Letizia AG, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission among marine recruits during quarantine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2407–16.

Bielecki M, et al. Reprint of: Air travel and COVID-19 prevention in the pandemic and peri-pandemic period: A narrative review. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;38:101939.

Epstein D, et al. Return to training in the COVID-19 era: The physiological effects of face masks during exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31(1):70–75.

Lynch JB, et al. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines on infection prevention for health care personnel caring for patients with suspected or known COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;27:ciaa1063.

Fikenzer S, et al. Effects of surgical and FFP2/N95 face masks on cardiopulmonary exercise capacity. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(12):1522–30.

Davies A, et al. Testing the efficacy of homemade masks: would they protect in an influenza pandemic? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(4):413–8.

Casar Berazaluce AM, et al. The chest wall gender divide: females have better cardiopulmonary function and exercise tolerance despite worse deformity in pectus excavatum. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36(11):1281–6.

Sciomer S, et al. Role of gender, age and BMI in prognosis of heart failure. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27(2_suppl):46–51.

Duncan MJ, et al. What is the impact of obtaining medical clearance to participate in a randomised controlled trial examining a physical activity intervention on the socio-demographic and risk factor profiles of included participants? Trials. 2016;17(1):580.

American Thoracic Society, American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):211–77.

Magnussen C, et al. FEV1 and FVC predict all-cause mortality independent of cardiac function - Results from the population-based Gutenberg Health Study. Int J Cardiol. 2017;234:64–8.

Zhang G, et al. Effect of Surgical Masks on Cardiopulmonary Function in Healthy Young Subjects: A Crossover Study. Front Physiol. 2021;12:710573.

Luks AM. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation: Including Pathophysiology and Clinical Applications. 4th ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Foster C, et al. A new approach to monitoring exercise training. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;15(1):109–15.

Zhang W, et al. The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation versus electroacupuncture on working memory in healthy subjects. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(6):637–42.

Liang J, et al. The lower body positive pressure treadmill for knee osteoarthritis rehabilitation. J Vis Exp. 2019;149.

Bai Y, et al. Comparative evaluation of heart rate-based monitors: apple watch vs fitbit charge HR. J Sports Sci. 2018;36(15):1734–41.

Lässing J, et al. Effects of surgical face masks on cardiopulmonary parameters during steady state exercise. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):22363.

Driver S, et al. Effects of wearing a cloth face mask on performance, physiological and perceptual responses during a graded treadmill running exercise test. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(2):107–13.

Ahmadian M, et al. Does wearing a mask while exercising amid COVID-19 pandemic affect hemodynamic and hematologic function among healthy individuals? Implications of mask modality, sex, and exercise intensity. Phys Sportsmed. 2021:1–12.

Chughtai AA, et al. Compliance with the use of medical and cloth masks among healthcare workers in Vietnam. Ann Occup Hyg. 2016;60(5):619–30.

Lässing J, et al. Decreased exercise capacity in young athletes using self-adapted mouthguards. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2021;121(7):1881–8.

Shaw K, et al. Wearing of cloth or disposable surgical face masks has no effect on vigorous exercise performance in healthy individuals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):8110.

Hopkins SR, et al. Face masks and the cardiorespiratory response to physical activity in health and disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(3):399–407.

Gregor RJ, Broker JP, Ryan MM. The biomechanics of cycling. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1991;19(1):127–69.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge PT Anniwaer Yilifate, the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, for his help in proof reading.

Data sharing

The data and trial protocol are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request (qianglin0925@gzhmu.edu.cn).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 81902281, the Guangzhou Municipal Health and Family Planning under Grant No. 20211A011106 and 20211A010079, Guangzhou Key Medical Disciplines (2021-2023), and the Guangzhou Key Laboratory Fund under Grant No. 201905010004. The funders had not role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data, and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HNO and YXZ are joint first authors. QL and HXC obtained funding. QL, HNO, and HXC designed the study. QL, HNO, and YXZ drafted the manuscript. ML, JJL, and HXC performed data analysis. SJL, QYL, DLC, YWL, QXC, YCJ, MFZ and TTY collected the data. HXC, QL and HNO approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project received the Ethics Review Committee approvement from Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (No. KY01–2020-06-06). Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ou, H., Zheng, Y., Li, M. et al. The impacts of surgical mask in young healthy subjects on cardiopulmonary function and muscle performance: a randomized crossover trial. Arch Public Health 80, 138 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00893-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00893-4