Abstract

Background

Chronic conditions are a leading cause of death and disability worldwide and respective data on dietary patterns remain scant. The present study aimed to investigate dietary patterns and identify sociodemographic factors associated with Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) scores within a multi-ethnic population with various chronic conditions.

Methods

The present study utilised data from the 2019-2020 Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices study on diabetes in Singapore – a nationwide survey conducted to track the knowledge, attitudes, and practices pertaining to diabetes. The study analysed data collected from a sample of 2,895 Singapore residents, with information from the sociodemographic section, DASH diet screener, and the modified version of the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3.0 checklist of chronic physical conditions.

Results

Respondents with no chronic condition had a mean DASH score of 18.5 (±4.6), those with one chronic condition had a mean DASH score of 19.2 (±4.8), and those with two or more chronic conditions had a mean DASH score of 19.8 (±5.2). Overall, the older age groups [35– 49 years (B = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.23 – 2.33, p <0.001), 50–64 years (B = 2.86, 95% CI: 22.24 – 3.47, p <0.001) and 65 years and above (B = 3.45, 95% CI: 2.73 – 4.17, p <0.001)], Indians (B = 2.54, 95% CI: 2.09 – 2.98, p <0.001) reported better diet quality, while males (B = -1.50, 95% CI: -1.87 – -1.14, p <0.001) reported poorer diet quality versus females.

Conclusion

Overall, respondents with two or more chronic conditions reported better quality of diet while the sociodemographic factors of age, gender and ethnicity demonstrated a consistent pattern in correlating with diet quality, consistent with the extant literature. Results provide further insights for policymakers to refine ongoing efforts in relation to healthy dietary practices for Singapore.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, chronic conditions are defined as “conditions lasting a year or more that require ongoing medical attention and/or limit activities of daily living” [1]. Chronic conditions are an ongoing cause of substantial ill health, disability, and premature death, making them an important global, national, and individual health concern [2]. Based on the latest statistics from the World Health Organization, it is estimated that the contribution of major chronic conditions toward death and global burden of disease is approximately 71% as of 2021 [3].

Globally, one in three adults live with multiple chronic conditions (MCC) [4], a figure that is expected to rise significantly with studies suggesting that the proportion of patients with four or more diseases is expected to double by 2035 in countries such as the United Kingdom [5]. MCC has long been associated with adverse health outcomes, with individuals experiencing early mortality [6], poorer physical and mental health [7] and reduced quality of life [8]. Additionally, given the complexities of clinical treatment and patient management, MCC is consequently associated with higher resource utilisation and increased medical costs [9, 10]. Specifically, average per capita health care spending increases exponentially with the number of chronic conditions – a figure estimated at $1,081 for people with no chronic conditions to $5,074 for those with two chronic conditions and $14,768 for people with five or more chronic conditions [11].

The etiology of chronic conditions is complex and multifactorial. Risk factors include age, family history, genetic predisposition, current and lifetime weight and physical activity, smoking, alcohol, and diet [12, 13]. Of these risk factors, dietary choices may arguably be the most amenable to modification and with the greatest public health impact [14]. Of note, Sofi et al. [15] highlighted that individuals reporting a greater degree of adherence to healthier dietary intake such as the Mediterranean diet showed a significant protection against the development of chronic conditions; with approximately 6-13% reduction in deaths and/or incidence of neurodegenerative disease, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Evidently, such a dietary pattern is recognised as a major contributing factor towards the prevention, development and treatment of chronic conditions [15]. Correspondingly, a growing and evolving body of scientific inquiry on dietary intake with health and chronic conditions has led to recommendations emphasizing a variety of plant-based foods (e.g., vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds) and de-emphasising processed food consumption with added sugar or a diet that is rich in meat content [14, 16].

Studies in Asian populations have identified various dietary patterns labelled “traditional,” “meat,” “Western,” and “prudent”. Dietary patterns observed in China characterised by a high intake of meat and dairy products have been associated with obesity [17, 18]. In Thailand, a more traditional carbohydrate-rich pattern was associated with metabolic syndrome [19]. In other populations such as Japan and Korea, a more traditional dietary pattern was inversely associated with risk factors such as high blood pressure [20, 21]. In Pakistan where 33% of the adult population suffers from hypertension, the high intake of fish, prawns and yoghurt was found to be inversely associated with hypertension [22]. Within the Singapore Chinese population, a “fruit-vegetable-soy” pattern was inversely associated, and a “meat-dim-sum” pattern was directly associated with cardiovascular disease mortality [23]. Evidently, the association between various dietary patterns and chronic conditions has been established within singular ethnic populations across the considerable corpus of research in this area. Yet, much less is known regarding the association between healthy dietary patterns and chronic conditions across a multi-ethnic population.

Singapore is a multi-ethnic city-state situated in Southeast Asia with a population of approximately 5.6 million of which 4.1 million are Singapore residents (Singapore citizens or permanent residents) [24]. The population is largely comprised of inhabitants from three major Asian ethnic groups: Chinese (76.0%), Malay (15.0%) and Indian (7.5%) [25]. Based on the results from the Singapore Mental Health Study, it was found that a total of 25.4% individuals reported having one chronic condition, and 16.3% had MCC [26]. Given the relatively substantial figures of individuals living with chronic conditions, it underscores the need to address the paucity of dietary data in this population. Additionally, a study in this setting provides a unique opportunity to elucidate the dietary patterns of a multi-ethnic population, the results of which can be extrapolated to other countries with a similar ethnic composition.

Given the diverse ethnic composition in Singapore, it follows that a culturally relevant diet screener is required for use in this multi-ethnic population. Whitton et al. [27] developed a reliable and validated short diet screener designed to assess the intake of selected food groups that is representative of the overall dietary patterns across a multi-ethnic Asian population. Specifically, the short 37-item diet screener assesses the intake of selected food groups representative of a multi-ethnic Asian population via a priori dietary quality indices such as DASH. In the extant literature, DASH has been demonstrated to be the most sensitive diet score to examine associations between diet and various health-related outcomes [28]. Adopting DASH dietary patterns has several benefits including but not limited to lowered mortality from cardiovascular diseases and diabetes [28, 29], lowered blood pressure [30], decreased body weight and waist circumference in obesity related weight management [31].

Taken together, the aims of the present study were to (1) characterise and examine the dietary patterns of a multi-ethnic population between persons with no chronic condition, one chronic condition and MCC through scoring their dietary intake according to the DASH score, and (2) identify socio-demographic correlates of DASH scores amongst persons with no chronic condition, one chronic condition and MCC.

Methods

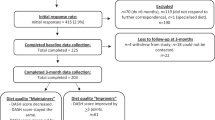

Participants and procedures

The data for this research comes from a population based, cross-sectional study lasting from February 2019 to September 2020 aimed at evaluating the Knowledge, Practice and Attitudes towards Diabetes Mellitus (DM) amongst residents of Singapore aged 18 years and above. A more to detailed methodology of the study can be found in an earlier paper [32]. The sample was randomly selected via a disproportionate stratified sampling design according to ethnicity (Chinese, Malay, Indian, Others) and age groups (18-34, 35-49, 50-64, 65 and above) from a national population registry database of all citizens and permanent residents within Singapore. The study oversampled certain minority populations, such as Malay and Indian ethnicity, as well as those above 65 years of age, in order to ensure sufficient sample size and to improve the reliability of the parameter estimates for these subgroups.

Citizens and permanent residents who were randomly selected were sent notification letters followed by home visits by a trained interviewer from a survey research company to obtain their informed consent to participate in the study. Face-to-face interviews with those who were agreeable to participate were conducted in their preferred language (English, Mandarin, Malay, or Tamil). Responses were captured using computer assisted personal interviewing. Individuals who were unable to be contacted due to incomplete or incorrect addresses, were living outside of the country, or were incapable of attending the interview due to severe physical or mental conditions, language barriers, or were institutionalized or hospitalized at the time of the survey were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents prior to the survey, and for those aged 18 to 20 years, parental consent was sought as the official age of majority in Singapore is 21 years and above.

Measures

Socio-demographic information and body mass index

Socio-demographic data on age (18-34, 35-49, 50-64 and 65 and above), gender (Female, Male), ethnicity (Chinese, Malay, Indian and Others), education (Primary and below, Secondary, Pre-U/Junior College, Vocational Institute/ITE, Diploma, Degree, professional certifications and above), marital status (Single, Married/Cohabiting, Divorced/Separated/Widowed), employment (Employed, Economically inactive and Unemployed), and monthly personal income (Below $2,000 and no income, $2,000-$3,999, $4,000-$5,999, $6000-$9,999 and $10,000 and above) was collected. Further, Body Mass Index (BMI) scores were categorised into four groups based on World Health Organization guidelines: ‘underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), ‘normal range’ (≥ 18.5 kg/m2 and < 25 kg/m2), ‘overweight’ (≥ 25 kg/m2 and < 30 kg/m2), and ‘obese’ (>30 kg/m2) [33].

Diet screener

The diet screener comprises a list of 30 food/beverage items, that respondents’ rate on a 10-point scale ranging from ‘never/rarely’ to ‘6 or more times per day’, the frequency at which they consumed a particular food/beverage within the last one year [27]. Accordingly, scores obtained from the list of 30 food/beverage items are categorised into each of the seven intake components: fruit, vegetables, nuts/legumes, whole grains, red and processed meat, low fat dairy, and sweetened beverages. Based upon the scores within each of the seven components, participants received a score between 1 and 5 corresponding to the quintile of the intake they fall in, with reverse scoring utilized for meat and sweetened beverages. Followingly. these seven quintile scores are summed to form the overall DASH score. Standard serving sizes were indicated for each food/beverage item to facilitate this process. Intake frequencies were standardised to a number of servings per day for each food/beverage item. Fung et al. [34] provides a detailed description on the calculation of DASH scores. The diet screener was interviewer-administered.

Chronic physical conditions

A modified version of the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 3.0 [35] checklist of chronic conditions was used, and the respondents were asked to report any of the conditions listed in the checklist. The question was read as, “I am going to read to you a list of health problems some people have. Has a doctor ever told you that you have any of the following chronic medical conditions?” This was followed by a list of 18 chronic physical conditions (such as asthma, high blood sugar, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, neurological condition, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, heart disease, back problems, stomach ulcer, chronic inflamed bowel, thyroid disease, kidney failure, migraine headaches, chronic lung disease, and hyperlipidaemia) which were considered to be prevalent among Singapore’s population. If the participant gave a positive response for any of the conditions listed, they were then asked, “How old were you when you were diagnosed with the medical condition?” and, “Did you receive any treatment for it at any time during the past 12 months?”.

Statistical analysis

Analyses in the present study were conducted with Stata version 15. In order to ensure representativeness of the data to the general population, survey weights were used to account for complex survey design. Means and standard deviations are provided for continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages are presented for categorical variables. In order to examine the variables associated with the total DASH score, four linear regressions were conducted (within the total sample, and the three subgroups of no chronic condition, one chronic condition and multimorbidity) with the following predictor variables: age, gender, ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, personal income, BMI and chronic conditions. Statistical significance was set at the conventional alpha level of p < 0.05, using two-tailed tests.

Results

Socio-demographics distribution and prevalence of physical comorbidities of the sample

Table 1 summarises the socio-demographic characteristics for the sample of 2,895 respondents. Chinese respondents made up 75.8% of the sample distribution, Malays 12.7%, Indians 8.6%, and Others 2.9%. 51.6% of the respondents were female, and BMI scores indicated that 53.4% of the respondents were in the normal range based on WHO BMI classification. 46.2% had no chronic physical condition, 26.3% had one chronic physical condition, and 27.2% had two or more chronic physical conditions. The most prevalent chronic condition was hyperlipidemia (22.2%, n=640), followed by hypertension (20.6%, n=668), high blood sugar (10.5%, n=465), back problems (10.2%, n=252), and asthma (9.9%, n=324). The results describing the prevalence of the different types of chronic physical conditions are displayed in Table 2.

DASH components score distribution and comparisons between chronic physical condition groups

The means and standard deviations of each of the seven DASH components (fruit, vegetables, nuts/legumes, low fat dairy, whole grains, red and processed meat, and sweetened beverages) and the overall DASH scores of the total sample, those with no chronic physical condition, one chronic physical condition and two or more chronic physical conditions are displayed in Table 3.

Socio-demographic correlates of DASH score

Table 4 shows the socio-demographic correlates associated with DASH scores within the full sample and across the three chronic physical condition groups. Within the full sample, the older age group [35– 49 years (B = 1.78, 95% CI: 1.23 – 2.33, p <0.001), 50–64 years (B = 2.86, 95% CI: 2.24 – 3.47, p <0.001) and 65 years and above (B = 3.45, 95% CI: 2.73 – 4.17, p <0.001)] had significantly higher DASH scores as compared to those aged 18-34. Males reported significantly lower DASH scores (B = -1.50, 95% CI: -1.87 – -1.14, p <0.001) than females. Indians (B = 2.54, 95% CI: 2.09 – 2.98, p <0.001) had significantly higher DASH scores than Chinese. Respondents who were less educated [primary and below (B = -1.99, 95% CI: -2.69 – -1.29, p <0.001), secondary (B = -1.72, 95% CI: -2.31 – -1.12, p <0.001), vocational institute/ITE (B = -1.42, 95% CI: -2.15 – -0.69, p <0.001), and diploma (B = -0.84, 95% CI: -1.40 – -0.27, p =0.004)] had significantly lower DASH scores than those with degree, and above qualifications.

Across all three groups, the older age groups reported [no chronic physical condition group: 35– 49 years (B = 1.77, 95% CI: 1.02 – 2.52, p <0.001), 50–64 years (B = 2.38, 95% CI: 1.47 – 3.28, p <0.001) and 65 years and above (B = 3.41, 95% CI: 2.20 – 4.63, p <0.001), one chronic physical condition group: 35– 49 years (B = 1.54, 95% CI: 0.45 – 2.63, p =0.01), 50–64 years (B = 2.87, 95% CI: 1.67 – 4.07, p <0.001) and 65 years and above (B = 4.19, 95% CI: 2.76 – 5.63, p <0.001) and two or more chronic physical condition group: 35– 49 years (B = 2.90, 95% CI: 1.52 – 4.27, p =0.001), 50–64 years (B = 4.10, 95% CI: 2.78 – 5.41, p <0.001) and 65 years and above (B = 3.87, 95% CI: 2.45 – 5.29, p <0.001)] significantly higher DASH scores as compared to those aged 18-34.

Males reported [no chronic physical condition group: (B = -1.89, 95% CI: -2.42 – -1.35, p <0.001), one chronic physical condition group: (B = -0.97, 95% CI: -1.71 – -0.22, p =0.01) and two or more chronic physical condition (B = -1.48, 95% CI: -2.19 – -0.77, p <0.001)] significantly lower DASH scores than females.

Respondents of Indian ethnicity reported [no chronic physical condition group: (B = 2.65, 95% CI: 1.99 – 3.31, p <0.001), one chronic physical condition group: (B = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.30 – 3.09, p <0.001) and two or more chronic physical condition group: (B = 2.61, 95% CI: 1.78 – 3.44, p <0.001)] significantly higher DASH scores than Chinese.

In the no chronic physical condition group, respondents who were less educated [primary and below (B = -2.06, 95% CI: -3.23 – -0.88, p =0.001), secondary (B = -1.42, 95% CI: -2.28 – -0.57, p =0.001), vocational institute/ITE (B = -1.75, 95% CI: -2.77 – 0.73, p =0.001)] had significantly lower DASH scores than those with degree, professional certification and above. Similarly, respondents with lower education in the one chronic physical condition group [primary and below (B = -3.04, 95% CI: -4.39 – -1.69, p <0.001), secondary (B = -2.35, 95% CI: -3.54 – -1.16, p <0.001), diploma (B = -1.51, 95% CI: -2.61 – -0.40, p =0.01)] had significantly lower DASH scores in contrast to their counterparts with degree, professional certification and above. In the two or more chronic physical condition group, respondents of “Others” ethnicities (B = 1.49, 95% CI: 0.01 – 2.97, p =0.04) demonstrated significantly higher DASH scores than Chinese ethnicity.

Discussion

The current study found that 42.9% of the population had no chronic physical condition, 26.3% had one chronic physical condition, and 30.5% had MCC. Overall, people with MCC had demonstrated better dietary practices in terms of number of servings taken per day for the DASH components. In the context of Singapore, this could be attributed to various initiatives and support received from primary care providers. Firstly, the focus upon nudging and facilitating healthier dietary choices is seen across the multitude of nationwide health promotion campaigns. One such example relates to the “Healthier Dining Programme” launched in 2014 which provides incentives to restaurants offering 500-calorie meals. Essentially, consumers are “nudged” towards choosing such healthier meal options that are identified with a “Healthier Choice Symbol” on menus in these restaurants (36). More importantly, better dietary practices amongst persons with MCC can also be attributed to the role of primary care providers as outlined in several guidelines and regulations. Of relevance, the “Chronic Disease Management Programme” introduced earlier in 2006 represents one avenue aiding in the management of chronic physical conditions in Singapore [37]. Briefly, the programme involves structured disease management aimed at reducing out-of-pocket payments for outpatient treatments required in the management of an individual’s chronic diseases [38]. In terms of dietary habits, healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians and dieticians) provide individuals with practical dietary guidelines aimed at making adjustments to current dietary choices [39]. Taken together, the combination of both healthier dietary practices campaigns and prevention efforts in the clinical setting provide plausible explanations to the present finding of better dietary patterns observed in persons with MCC.

Findings from the present study lends further support to several well-established risk factors associated with diet quality in the extant literature. Within the study population, females and those of older age reported better diet quality based on their respective DASH scores. In a study determining the demographic profile of fast-food consumers amongst a Singapore population, Whitton et al. [40] reported that older adults consumed lesser fast food in comparison to their younger counterparts. As highlighted by Allman-Farinelli et al. [41], this is consistent with the notion that younger individuals demonstrate certain dietary habits that reduce overall diet quality. Food and beverages with high saturated fat, sugar and sodium contents such as those purchased at quick service restaurants feature prominently in the younger population’s diet across many countries such as USA, UK and Australia [41].

Gender differences in terms of dietary patterns was also demonstrated to be consistent with prior studies; where women tended to report better diet quality in comparison to men. For example, in Montreal, women’s diets were closer to recommendations for vegetables, fruits, and sodium intake as compared to men [42]. As demonstrated in prior literature, women generally reported being more invested in relation to food-related matters and having better knowledge in terms of food and nutrition [43, 44]. Additionally, women reported consuming higher intakes of fruits and vegetables, dietary fibre, and lower intakes of fat and salt [43, 45]. Taken together, it follows that greater importance attributed by women to their diet correspondingly translates into better dietary practices.

Across the sample population, ethnicity was also identified to be significantly associated with diet quality. Among the major ethnic groups in Singapore, Indians reported having healthier diet based on respective DASH scores. This is consistent with the healthy dietary pattern as outlined in the National Nutrition Survey conducted in 2010 [46], with Indians consuming the most bread and breakfast cereals, vegetable dishes, fruit, milk and dairy products and fewer eggs, poultry and meat dishes.

Diet and nutrition represent important factors in both promotion and maintenance of good health throughout the entire life course. We identified several important factors associated with diet quality among persons with no chronic conditions and one chronic condition. Within these subgroups, education level was significantly associated with diet quality. Specifically, those with less than a degree reported having poorer diet quality. Similar findings regarding educational level have been reported elsewhere; adults with a college diploma in USA demonstrated having a better overall diet quality as compared to all other education levels [47]. Therein, it has been posited that education might be associated not only with increased nutritional knowledge, but could also be an indicator of ability to translate such nutritional knowledge into better dietary practices throughout the person’s lifetime [47]. Lastly, it was interesting to observe that BMI was not a factor associated with diet quality in the present study. In current literature, it has been evidenced that individuals with chronic conditions generally reported higher-than-normal BMI (48). Accordingly, multiple studies have also demonstrated that healthier dietary patterns are associated with lower BMI [49, 50]. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the use of self-reported chronic conditions may plausibly have resulted in reporting bias – underestimating the true prevalence of chronic conditions and therein, an underestimation of the strength of the association between BMI and diet quality.

The present study was a nationwide survey conducted in four different languages (English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil) to address potential language barriers for participation in a multi-ethnic population. Additionally, the use of a large sample size, randomised design and survey weighted analysis improves the overall reliability of the present results. Nonetheless, several limitations of the present study warrant comment and conclusions drawn should be considered in light of these limitations. Firstly, given that the present study adopts a cross-sectional design, we are not able to establish any causal relationship between dietary pattern and chronic conditions. Secondly, the diet screener utilised is fundamentally based on the past-year self-reported diet recall of the respondent, with no correlation to any blood or urinary parameters. In that regard, we are not able to rule out the likelihood of recall bias in this self-reported format. Additionally, while it has been demonstrated that intakes such as whole grains and fruits can be adequately assessed in the present diet screener, more comprehensive and detailed instruments such as comprehensive food frequency questionnaires are still recommended for the assessment of other dietary components such as nutrients.

Conclusion

Chronic conditions remain the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Despite this, it should be noted that chronic conditions are largely preventable, and dietary patterns play a key role in such prevention activities. Given its significance, it reasons that establishing population norms in relation to dietary habits represent an important aspect of research in this area. Given the limited research conducted regarding dietary patterns of a multi-ethnic population, the present study furthers the understanding on the dietary patterns of a multi-ethnic population like Singapore. Notably, while the dietary patterns of individuals with chronic conditions are positive, the present study highlights areas of improvement for better dietary practices amongst individuals without chronic conditions. Given that individuals who are younger and healthy at present tended to have lower DASH scores, it is critical that efforts are directed towards monitoring less-than-ideal dietary practices given its significance towards the development of chronic conditions. As noted earlier, ongoing efforts such as the “Healthier Dining Programme” are initiatives aimed at providing healthier meals for individuals. Results on the dietary intakes as categorised by food groups such as fruits and vegetables provide up-to-date information which policymakers can utilise to modify ongoing initiatives and campaigns if necessary. In the global context, studies and reviews have generally reached the conclusion that there are some similarities in terms of dietary recommendations albeit minor differences when a country’s geographical environment and culture are taken into account [51, 52]. Accordingly, information obtained from the present study may provide certain insights to international counterparts pertaining to the effectiveness of diet related policies and initiatives in Singapore. Such information may be useful in aiding policymakers with modifying or forming new polices to better suit their respective population. Taken together, the present study provides both local and international policymakers with up-to-date information on dietary patterns in Singapore to better support the design and evaluation of policies and initiatives.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DASH:

-

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- CIDI:

-

World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- MCC:

-

Multiple Chronic Conditions

- DM:

-

Diabetes Mellitus

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- Pre-U:

-

Pre-University

- ITE:

-

Institute of Technical Education

- SGD:

-

Singapore Dollars

References

Multiple chronic conditions. A strategic framework optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1037/e507192011-001.

Chronic conditions and multimorbidity. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2020 https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/chronic-conditions-and-multimorbidity.

World Health Organization. 2021. Non communicable diseases. WHO | World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, Meinow B, Fratiglioni L. Aging with multimorbidity: A systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003.

Kingston A, Robinson L, Booth H, Knapp M, Jagger C. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: Estimates from the population ageing and care simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing. 2018;47(3):374–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx201.

Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, Van den Bos GA. Causes and consequences of comorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):661–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00363-2.

Kadam U, Croft P. Clinical multimorbidity and physical function in older adults: A record and health status linkage study in general practice. Fam Pract. 2007;24(5):412–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmm049.

Pati S, Swain S, Hussain MA, Van den Akker M, Metsemakers J, Knottnerus JA, Salisbury C. Prevalence and outcomes of multimorbidity in South Asia: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e007235. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007235.

Lehnert T, Heider D, Leicht H, Heinrich S, Corrieri S, Luppa M, Riedel-Heller S, König H. Review: Health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68(4):387–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558711399580.

Sambamoorthi U, Tan X, Deb A. Multiple chronic conditions and healthcare costs among adults. Expert Rev PharmacoEcon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(5):823–32. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737167.2015.1091730.

Anderson GF. Chronic care: making the case for ongoing care. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010.

Adams ML, Grandpre J, Katz DL, Shenson D. The impact of key modifiable risk factors on leading chronic conditions. Prev Med. 2019;120:113–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.01.006.

Oates GR, Jackson BE, Partridge EE, Singh KP, Fouad MN, Bae S. Sociodemographic patterns of chronic disease: How the mid-south region compares to the rest of the country. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1):31–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.004.

Neuhouser ML. The importance of healthy dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention. Nutr Res. 2019;70:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2018.06.002.

Sofi F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A. Accruing evidence on benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on health: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1189–96. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29673.

Bishwajit G. Nutrition transition in South Asia: The emergence of non-communicable chronic diseases. F1000Research. 2015;4:8. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.5732.1.

Zhang Q, Chen X, Liu Z, Varma D, Wan R, Wan Q, Zhao S. Dietary patterns in relation to general and central obesity among adults in Southwest China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(11):1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13111080.

Yu C, Shi Z, Lv J, Du H, Qi L, Guo Y, Bian Z, Chang L, Tang X, Jiang Q, Mu H, Pan D, Chen J, Chen Z, Li L. Major dietary patterns in relation to general and central obesity among Chinese adults. Nutrients. 2015;7(7):5834–49. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7075253.

Aekplakorn W, Satheannoppakao W, Putwatana P, Taneepanichskul S, Kessomboon P, Chongsuvivatwong V, Chariyalertsak S. Dietary pattern and metabolic syndrome in Thai adults. J Nutri Metabolism 2015, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/468759.

Akter S, Nanri A, Pham NM, Kurotani K, Mizoue T. Dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome in a Japanese working population. Nutr Metabolism. 2013;10(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-10-30.

Kim J, Jo I. Grains, vegetables, and fish dietary pattern is inversely associated with the risk of metabolic syndrome in South Korean adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(8):1141–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.001.

Safdar NF, Bertone-Johnson E, Cordeiro L, Jafar TH, Cohen NL. Dietary patterns and their association with hypertension among Pakistani urban adults. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutri. 2015; 24(4).

Odegaard AO, Koh W, Yuan J, Gross MD, Pereira MA. Dietary patterns and mortality in a Chinese population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(3):877–83. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.086124.

Singapore population. 2020. Base. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/modules/infographics/population.

What are the racial proportions among Singapore citizens? (2019). gov.sg. https://www.gov.sg/article/what-are-the-racial-proportions-among-singapore-citizens.

Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Picco L, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA. Multiple chronic medical conditions: Prevalence and risk factors — results from the Singapore mental health study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(4):375–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.03.002.

Whitton C, Ho JC, Rebello SA, Van Dam RM. Relative validity and reproducibility of dietary quality scores from a short diet screener in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(15):2735–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980018001830.

Whitton C, Rebello SA, Lee J, Tai ES, Van Dam RM. A healthy Asian a posteriori dietary pattern correlates with a priori dietary patterns and is associated with cardiovascular disease risk factors in a multiethnic Asian population. J Nutr. 2018;148(4):616–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxy016.

Folsom A, Parker E, Harnack L. Degree of concordance with DASH diet guidelines and incidence of hypertension and fatal cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(3):225–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.09.003.

Filippou C, Thomopoulos C, Mihas C, Dimitriadis K, Sotiropoulou L, Siafi E, Zammanis I, Dimitriadi M, Chrysochoou C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Tousoulis D, Tsioufis C. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet and blood pressure reduction in adults with and without hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2020; 41. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/ehaa946.2765.

Paula Bricarello L, Poltronieri F, Fernandes R, Retondario A, De Moraes Trindade EB, De Vasconcelos FD. Effects of the dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) diet on blood pressure, overweight and obesity in adolescents: A systematic review. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;28:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.09.003.

AshaRani P, Abdin E, Kumarasan R, Siva Kumar FD, Shafie S, Jeyagurunathan A, Chua BY, Vaingankar JA, Fang SC, Lee ES, Van Dam R, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. Study protocol for a nationwide knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) survey on diabetes in Singapore’s general population. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e037125. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037125.

WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004 Jan;363(9403):157–63.

Fung TT. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(7):713. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.7.713.

Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.168.

HPB steering singaporeans to eat healthier. (2016). The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/hpb-steering-singaporeans-to-eat-healthier.

HPB steps up health campaign to engage more S’poreans. (2016). The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/hpb-steps-up-health-campaign-to-engage-more-sporeans.

Living well with chronic conditions - NUHS | National University health system. https://www.nuhs.edu.sg/Care-in-the-Community/Living-Well/Pages/default.aspx.

Foo KM, Sundram M, Legido-Quigley H. (2019). Facilitators and barriers of managing patients with multiple chronic conditions in the community: A qualitative study. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.15520/v2.

Whitton C, Ma Y, Bastian AC, Chan F, M., & Chew L. Fast-food consumers in Singapore: Demographic profile, diet quality and weight status. Public Health Nutr. 2013;17(8):1805–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980013001997.

Allman-Farinelli M, Partridge SR, Roy R. Weight-related dietary behaviors in young adults. Curr Obes Rep. 2016;5(1):23–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-016-0189-8.

Shatenstein B, Nadon S, Godin C, Ferland G. Diet quality of Montreal-area adults needs improvement: Estimates from a self-administered food frequency questionnaire furnishing a dietary indicator score. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(8):1251–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2005.05.008.

Grzymisławska M, Puch E, Zawada A, Grzymisławski M. Do nutritional behaviors depend on biological sex and cultural gender? Adv Clin Experimental Med. 2020;29(1):165–72. https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/111817.

Li K, Concepcion RY, Lee H, Cardinal BJ, Ebbeck V, Woekel E, Readdy RT. An examination of sex differences in relation to the eating habits and nutrient intakes of University students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(3):246–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2010.10.002.

Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisie F. Gender differences in food choice: The contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(2):107–16. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2702_5.

Health Promotion Board. National Nutrition Survey 2010 [Internet]. Singapore: Health Promotion Board; 2013 [cited 2021 Apr 30]. Available from: https://www.hpb.gov.sg/docs/default-source/pdf/nns-2010-report.pdf?sfvrsn=18e3f172_2.

Hiza HA, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2013;113(2):297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.011.

New England Journal of Medicine, 364(8), 719-729. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1010679.

Fogelholm M, Anderssen S, Gunnarsdottir I, Lahti-Koski M. Dietary macronutrients and food consumption as determinants of long-term weight change in adult populations: A systematic literature review. Food & Nutrition Research. 2012;56(1):19103. https://doi.org/10.3402/fnr.v56i0.19103.

Newby P, Muller D, Hallfrisch J, Qiao N, Andres R, Tucker KL. Dietary patterns and changes in body mass index and waist circumference in adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(6):1417–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1417.

Herforth A, Arimond M, Álvarez-Sánchez C, Coates J, Christianson K, Muehlhoff E. A global review of food-based dietary guidelines. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(4):590–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy130.

Rong S, Liao Y, Zhou J, Yang W, Yang Y. Comparison of dietary guidelines among 96 countries worldwide. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;109:219–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.01.009.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants and staff involved in the study.

Funding

This research funding was provided by National Medical Research Council of Singapore (NMRC/HSRG/0085/2018). The funding bodies did not have any role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS, AN, LES, and SCF conceptualised the design of the study. MS, AN, FD, KR, WP, LES, and SCF were involved in questionnaire design. EA provided the statistical design and sampling strategy, while JHL analysed and interpreted the data. LYY, CW, SS, SC, AJ and CBY have substantively revised the work. YWBT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors provided intellectual input in the development of the article. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the relevant ethics committee (Domain Specific Review Board, National Healthcare Group, Singapore), and all respondents provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Consent for publication

N.A.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, Y.B., Lau, J.H., AshaRani, P. et al. Dietary patterns of persons with chronic conditions within a multi-ethnic population: results from the nationwide Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices survey on diabetes in Singapore. Arch Public Health 80, 62 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00817-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-022-00817-2