Abstract

Background

Although several measures have been taken to control hand foot and mouth disease (HFMD) and herpangina (HA), these two diseases have been prevalent in China for 10 years with high incidence. We suspected that adults’ inapparent infection might be the cause of the continued prevalence of HFMD/HA infection in mainland China.

Methods

To explore the role of adults (especially caregivers) in the transmission process of HFMD/HA among children, 330 HFMD/HA cases and 330 healthy children (controls) were selected for a case–control study. Then, data were analyzed by logistic regression.

Results

Single-variable analyses revealed that caregivers who tested positive for enterovirus was a significant risk factor of HFMD/HA transmission to children (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 9.22; 95% CI, 1.16 to 73.23). In the final multivariable model, caregiver behavior, such as cooling children’s food with mouth (OR = 1.85; 95% CI, 1.11 to 3.08) and feeding children with their own tableware (OR = 2.19; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.45), significantly increased the risk of transmitting HFMD/HA to children. On the contrary, washing hands before feeding children reduced such risk.

Conclusions

These results implied that the caregivers might be the infectious source or carriers of enterovirus. Therefore, preventing or treating the caregivers’ enterovirus infection and improving their hygiene habits, especially when they are in contact with children, could provide a breakthrough for the effective control of HFMD/HA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) and herpangina (HA) are caused by human enterovirus, especially by serotypes of human enterovirus 71 (EV71), coxsackievirus A, and coxsackievirus B [1]. As reported, HFMD/HA epidemics predominantly occur in the Asia–Pacific region [2], such as South Korea [3], Thailand [4], Vietnam [5]. For most cases, the symptoms of HFMD/HA are mild and self-limiting. However, severe complications, including myocarditis, acute flaccid paralysis, and even death, occur in a few cases [6, 7]. In China, HFMD has been a notifiable disease in 2008. From January 2004 to December 2013, the incidence of HFMD has ranked third in the incidence of infectious diseases [8]. Although the EV71 vaccine has been successfully licensed in 2016, approximately 2 million cases of HFMD are reported in China every year [9]. Thus, the prevalence of HFMD/HA in China remains severe.

At present, most studies on HFMD/HA suggest that nurseries and kindergartens are the primary sites for the transmission of infection [10]. Therefore, the prevention and control of HFMD/HA is mainly to take secondary prevention measures, that is, early detection, early report, early diagnosis, early treatment, and early isolation. During an HFMD/HA epidemic, children in nurseries and kindergartens should be screened in the morning, and suspected cases should be reported, isolated, and treated in time. In case of an HFMD/HA outbreak, measures are taken to close classes or kindergartens in strict accordance with school suspension standards. A series of measures plays a good regulating role in preventing the further spread of HFMD/HA among children living collectively [11, 12], thus greatly reducing the number of cases of mutual infection. However, among the 2 million reported cases of HFMD, children aged 1–2 have the highest risk of disease although they are generally scattered children who have no experience of living in nurseries or kindergartens. In addition, most of them have no clear history of patient contact. Therefore, how to reduce these primary infections has become the key issue to control the HFMD/HA epidemic in China.

Generally, the HFMD/HA epidemic can only be controlled effectively by containing HFMD/HA from the source, i.e., identifying the exact source and route of transmission. Consequently, different methods have been used in related studies. For example, Lu et al. [13] showed that children’s hospitals may have a crucial role in HFMD transmission. Wang et al. [14] established a mathematical model to illustrate the important role of asymptomatic infection and contaminated environments in new HFMD infections. In addition, the caregivers may have had contact with children with HFMD/HA or article surfaces with enterovirus attachment; then, as a vector of the enterovirus, transmit the virus to their children. Studies have also found that hand washing by caregivers is a protective factor for HFMD among children [15, 16], suggesting that transmission from adults to children is possible.

Hence, a case–control study was conducted to explore the role of caregivers in the transmission mechanism of HFMD/HA by analyzing data obtained from the cities of Guangzhou and Shaoguan. Thus, a theoretical basis for the prevention and control strategies and measures of HFMD/HA is provided from the perspective of caregivers.

Method

Study population

This study was conducted in the community health service center in Yonghe, Yongning Street, Zengcheng District, Guangzhou City and the Yuebei People’s Hospital of Shaoguan City between May 1, 2019 and June 30, 2019. All children aged five years old or younger and their caregivers who volunteered for the study were chosen by using the convenient sampling method. Then, throat swab samples of the caregivers were collected and stored at − 80 °C. In addition, the caregivers were asked to complete a study questionnaire.

Case and control groups

The clinical diagnosis criteria of HFMD cases included children who have the symptoms with fever; scattered herpes in oral mucosa; maculopapular rash and herpes in hands, feet, and buttocks; and inflammatory erythema around herpes. Moreover, the diagnosis criteria of herpangina cases included children who have the signs with anorexia, high fever, salivation, and vomiting; moreover, pale herpes could be observed in the soft palate, pharyngeal palatal arch, and the mucosa of the uvula. Children who had the above signs and were diagnosed with HFMD/HA by clinicians were defined as cases in the study. Furthermore, the cases were collected from the pediatric clinic of the Yonghe community health service center and the Yuebei People’s Hospital. A total of 330 cases were selected.

The control group in the study included healthy children who were recruited from the vaccination clinics of the Yonghe community health service center. Moreover, the control group had not suffered from HFMD/HA in the past months. All the children’s ages were divided into < 6 months old, ~ 6 months old, ~ 12 months old, ~ 24 months old, ~ 36 months old, ~ 48 months old, 60–71 months old. Then, 330 control–children who were matched to the case–children in terms of frequency by age group were selected.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire used in the study covered demographic information of the children (e.g., children’s age) and the caregivers (e.g., caregivers’ age; hygiene habits, such as washing hands before meals; behavior when looking after children, such as washing hands before feeding children). In order to ensure the validity of the questionnaire, the first draft of the questionnaire was designed through literature review, and then the final draft was determined through expert discussion and pre-investigation. All interviewers were systematically trained.

Laboratory methods

The throat swab specimens of caregivers were defrosted in a − 4 °C environment. Each 200 μl specimen was processed by using LogPure Viral RNA/DNA Kits (250 reactions) (Magen, Guangzhou, China). Lastly, 60 μl of viral RNA was extracted. Reverse transcription was conducted using a HiScript® II Q Select RT SuperMix for qPCR kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The primers for enterovirus were designed on the basis of other literature [17, 18]. Table 1 lists the details of the primers for enterovirus (Invitrogen Custom Primers, Shanghai). Next, 10 μl of 2 × qPCR mix (iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix, Bio-Rad, America), 1 μl of forward primer, 1 μl of reverse primer, 1 μl of probe, 3 μl of tri-distilled water and 4 μl s of cDNA sample were added into each PCR tube. Afterwrad, Taqman real-time PCR was conducted with a quantitative fluorescence analyzer (Bio-rad CFX96, America). All experiments were performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instruction. When the Ct value was greater than 20 or less than 40, corresponding specimens were considered positive.

Statistical analysis

Mean (SD) was used for continuous data, and categorical data were expressed as frequency (percentage, %). Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the potential risk factors of HFMD/HA infection among children by using SPSS ver. 25. Initially, statistically significant predictors were screened by single variable analysis. Then, the statistically significant variables were place into the multivariable model during stepwise regression. Moreover, children’s age as the control variable was placed into the multivariable logistic regression model. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to determine whether a variable is a risk factor of HFMD/HA infection in children. P < 0.1 indicated statistical significance in single-variable analysis, whereas P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance in the multivariable model. Stratified analysis was further performed to assess whether the associations between the variables and HFMD/HA among children were modified by demographic characteristics, such as children’s age. Moreover, 0.05 was chosen as the level of significance (P < 0.05).

Results

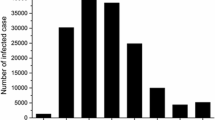

As shown in Tables 2, 27.6% (91/330) of the cases were aged between 12 and 23 months old, and the cases aged under 6 months old had the lowest rate with 2.1% (7/330); the same goes for the control group. Moreover, compared with children whose family monthly income was less than RMB 5000, children whose family monthly income was RMB 10000–30,000 and RMB 30000–50,000 had a higher risk of contracting HFMD/HA. In addition, compared with children whose families had no other children under five, children whose families had other children aged five and under were more likely to contract HFMD/HA (OR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.87). However, having extra-curricular classes was a protective factor (OR = 0.54; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.89) for HFMD/HA suffering in children. Otherwise, children’s gender, children’s current residence, and scattered children or not did not significantly differ between the case and control groups.

As shown in Table 3, caregivers’ age was positively associated with HFMD/HA among children (P < 0.1). Meanwhile, caregivers with a high education level could reduce the possibility of HFMD/HA among children. Compared with that of caregivers with primary education or below, the OR for HFMD/HA among children whose caregivers had junior high school education, senior high school education, college education, university education, and master education or above was 0.49, 0.45, 0.22, 0.37, and 0.50, respectively. In addition, the relationship between the children and caregivers was also associated with HFMD/HA among children. Compared with caregivers who were fathers, caregivers who were grandfathers or grandmothers significantly increased the risk of HFMD/HA among children (OR = 2.33; 95% CI, 1.31 to 4.13). Nevertheless, no statistical difference was found between fathers and mothers (OR = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.55 to 1.32). In addition, caregivers’ gender was not significantly different between the two groups.

In the single-variable analyses of caregivers’ hygiene habits (Table 4), “washing of hands of caregivers after using the bathroom” was not associated with HFMD/HA among children (P = 0.507). Compared with that of “almost always washing hands before meals,” the OR for “sometimes washing hands before meals” was 0.74 (95% CI, 0.55 to 1.02), and that for “never washing hands before meals” was 9.78 (95% CI, 1.25 to 76.62). In addition, “washing hands after going out” was a protective factor of HFMD/HA among children (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.91). Moreover, a similar HFMD/HA prevention effect could be found in “using soaps or hand sanitizers,” “washing hands for 20 seconds,” and “wiping hands after washing hands;” the ORs were 0.43 (95% CI, 0.32 to 0.59), 0.32 (95% CI, 0.23 to 0,45) and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.34 to 0.75), respectively.

As shown in Table 5, children whose caregivers tested positive for enterovirus were more likely to contract the disease (OR = 9.22; 95% CI, 1.16 to 73.23). Meanwhile, compared with “never kissing the children per day,” “kissing the children 1–3 times per day” (OR = 1.59; 95% CI, 1.13 to 2.24), “kissing the children 4–6 times per day” (OR = 2.57; 95% CI, 1.34 to 4.94) and “kissing the children more than 6 times per day” (OR = 2.37; 95% CI, 1.26 to 4.47) were risk factors of HFMD/HA among children. In addition, “washing hands before feeding the children,” “washing hands after defecating,” “preparing special utensils and towels for children,” “cooling children’s food with their mouth,” “feeding the children with their own tableware,” “disinfecting the tableware and bottles,” “disinfecting the toys,” “the number of times a week children are taken out,” and “the average time of outdoor activities for children every day” contributed to children’s HFMD/HA infection. However, no significant association was found between “caregivers and children sleeping in the same bedroom” and HFMD/HA among children.

Children’s ages, which were matching variables, and the variables that were statistically significant through single-variable analyses were included in the multivariable model (Table 6). Then, the final multivariable model identified the monthly income of RMB 10000–30,000 (OR = 5.43; 95% CI, 2.61 to 11.32) and RMB 30000 ~ 50,000 (OR = 16.38; 95% CI, 5.59 to 47.99), “cooling children’s food by blowing with their mouth” (OR = 1.85; 95% CI, 1.11 to 3.08), “always feeding the children with their own tableware” (OR = 2.19; 95% CI, 1.07 to 4.45), “taking children out twice a week” (OR = 3.87; 95% CI, 1.67 to 8.99), “taking children out thrice a week” (OR = 3.85; 95% CI, 1.34 to 11.08), “taking children out four times a week or more” (OR = 14.34; 95% CI, 6.97 to 29.49), and “an average of 4 hours and more of outdoor activities for children every day” (OR = 5.74; 95% CI, 1.78 to 18.49) as independent risk factors of HFMD/HA among children. By contrast, “having extra-curricular classes” (OR = 0.40; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.95), “caregivers with college education level or above,” “washing hands before feeding the children” and “disinfecting the toys” (OR = 0.12; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.21) were protective factors for HFMD/HA among children.

The results of stratified analysis by children’s age (under 3 years old and 3 years old and above) could be seen in Table 7. Regardless of children’s age, no statistical associations were found between having extracurricular class and HFMD/HA among children in the single-variable analysis model (P > 0.05). The same results could be found in the multivariable analysis model.

Discussion

HFMD/HA is generally regarded as children’s disease; thus, studies have focused on children aged five and under. Although adults could contract HFMD/HA, researchers have not paid enough attention to this group [19, 20]. Nevertheless, the findings of the present study suggested that adults, especially caregivers, might be the latent infectious source or carriers of children’s HFMD/HA.

In this study, nine (2.7%) caregivers in the case group and one (0.3%) caregiver in the control group tested positive for enterovirus. The single-variable analysis also showed that the caregiver who tested positive for enterovirus was a significant risk factor of HFMD/HA among children. However, after controlling for the age group and other factors, this factor (caregivers with enterovirus infection) was not included in the multivariable model because the number of caregivers who tested positive for enterovirus was too small. In our previous study, the positive rate for enterovirus of children’s caregivers was 7.14% [17]. Another previous study reported that the positive rate for enterovirus of sick children’s close contacts was 14.1% [21]. Furthermore, in consideration of the nondifferential misclassification bias between the case and control groups, the conclusion that caregivers who test positive for enterovirus increase the possibility of HFMD/HA among children is unchanged. Moreover, the inference that the caregivers probably transmit enterovirus to their children and even to other children they contacted with was reasonable [22, 23].

The study showed that compared with a monthly family income of less than RMB 5000, a monthly family income of RMB 10000–30,000 and RMB 30000–50,000 increased the risk of HFMD/HA infection in children. This result contradicts Chen’s study [24] probably because the present study was conducted in hospitals rather than in a village clinic, where high-income families preferred to see doctors for their children.

Taking “caregivers with primary education or below” as reference, “caregivers with college education or above” could reduce children’s risk of HFMD/HA; Chen’s study revealed a similar finding [24, 25]. Similar to other studies, the present study found that the higher the level of caregivers’ education, the richer the knowledge of HFMD/HA and the higher the awareness of acquiring new knowledge through various channels [26]. Meanwhile, our study revealed that having extra-curricular classes was a protective factor of HFMD/HA in children on the basis of the multi-variable non-conditioned logistic regression model. Generally, children who had extra-curricular class were school-aged children, not children under three years old who were susceptible to HFMD/HA [27, 28]. However, the difference of having extra-curricular classes between two groups had no significant when it was analysed with stratification according to children’s age. Therefore having extra-curricular class was not a significant influence factor of HFMD/HA among children.

This study also reveals that factors, such as “cooling children’s food by blowing with their mouth” and “always feeding the children with their own tableware,” increase risk of HFMD/HA among children. By contrast, “washing hands before feeding the children”and “disinfecting the toys” are protective factors. These findings are consistent with those of other studies [29,30,31]. The reason could be that although majority of adults infected with enterovirus are mostly recessive and healthy carriers, they can be the source of infection. In addition, enterovirus could also be transmitted through contact with respiratory secretions or feces of infected persons or contaminated hands or objects. All the results showed that the caregivers may be the infectious source or carriers of enterovirus in children. At the same time, children’s living habits and behavior are easily affected by their families and environment. Moreover, the health habits of children mainly depend on their caregivers. Therefore, to control HFMD/HA, caregivers’ enterovirus infection must be prevented, and some poor health habits, such as cooling children’s food by blowing with their mouth, must be stopped.

Lastly, this study also found that taking children out twice a week or more and an average of 4 h and more of outdoor activities for children every day increase the likelihood of contracting HFMD/HA among children. The studies of Feng et al. [15] and Xiang et al. [32] support our findings. A possible reason is that in crowded public places, pathogens could be carried by different individuals, making children susceptible to enterovirus infection. Therefore, caregivers should avoid taking children to crowded places or shorten the time outside with their children during an HFMD/HA epidemic.

This study has some limitations. First, most of the questionnaire content was about the survey of the healthy habits of the caregivers and thus was mainly based on the subjective judgment of the caregivers. Moreover, the caregivers intentionally exaggerated or minimized information about their health habits, leading to information bias. To control the information bias, all interviewers were professionally trained. Second, our study suggested that caregivers who tested positive for enterovirus were associated with HFMD/HA among children; however, a causal link between the two could not be established through a case–control study for the infection sequence of children and their caregivers could not be distinguished. In the future, a related cohort study should be conducted.

Conclusion

This study suggested that children’s caregivers with latent enterovirus infection might become a potential source of HFMD/HA among children. To control the sustaining epidemic of HFMD/HA in Guangdong, China, some approaches should be taken to prevent the transmission of caregivers’ enterovirus infection to children.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HFMD:

-

Hand foot and mouth disease

- HA:

-

Herpangina

- EV71:

-

Human enterovirus 71

- cDNA:

-

Complementary Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic Acid

- Ct:

-

Cycle threshold

- μl:

-

Microliter

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Zhou HT, Guo YH, Chen MJ, Pan YX, Xue L, Wang B, et al. Changes in enterovirus serotype constituent ratios altered the clinical features of infected children in Guangdong Province, China, from 2010 to 2013. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):399. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1690-0.

Solomon T, Lewthwaite P, Perera D, Cardosa MJ, Mcminn P, Ooi MH. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70194-8, 11.

Ryu WS, Kang B, Hong J, Hwang S, Kim J, Cheon DS. Clinical and etiological characteristics of enterovirus 71-related diseases during a recent 2-year period in Korea. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(7):2490–4. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02369-09.

Samphutthanon R, Tripathi NK, Ninsawat S, Duboz R. Spatio-temporal distribution and hotspots of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) in northern Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;11(1):312–36. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110100312.

Nguyen HX, Chu C, Nguyen H, Nguyen HT, Do CM, Rutherford S, et al. Temporal and spatial analysis of hand, foot, and mouth disease in relation to climate factors: a study in the Mekong Delta region, Vietnam. Sci Total Environ. 2017;581-582:766–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.006.

Zhang H, Yang L, Li L, Xu G, Zhang X. The epidemic characteristics and spatial autocorrelation analysis of hand, foot and mouth disease from 2010 to 2015 in Shantou, Guangdong. China Bmc Public Health. 2019;19(1):998. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7329-5.

Puenpa J, Auphimai C, Korkong S, Vongpunsawad S, Poovorawan Y. Enterovirus A71 infection, Thailand, 2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(7):1386–7. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2407.171923.

Yang S, Wu J, Ding C, Cui Y, Zhou Y, Li Y, Deng M, Wang C, Xu K, Ren J, Ruan B, Li L Epidemiological features of and changes in incidence of infectious diseases in China in the first decade after the SARS outbreak: an observational trend study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 716–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30227-X, 7.

National Health Commission Of The People'S Republic Of China TBOD. 2019. The situation of statutory infectious diseases throughout the country. Available from http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/pqt/new_list_4.shtml. .

Li F, Wu K, Li Y, Ren S, Yang Y, Du C, et al. Analysis on epidemic characteristics ofhand-foot-mouth disease outbreaks in Hongta District. Chin J Women and Children Health. 2018;9:24–8. https://doi.org/10.19757/j.cnki.issn1674-7763.2018.04.006.

Qian C, Gu M, Ma Y, Yao J, Shu F. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of hand-foot-mouth disease caused by cox A16 in a kindergarten. J Med Pest Contr. 2017;33:144–6. https://doi.org/10.7629/yxdwfz201702009.

Sheng S, Yang J, Zhang Z, Chen Y. The epidemiological investigation and disposal of an outbreak of hand, foot and mouth disease in a kindergarten. J Med Pest Contr. 2018;34:981–3. https://doi.org/10.7629/yxdwfz201810019.

Lu J, Sun L, Zeng H, Tan X, Lin H, Liu L, et al. Enterovirus contamination in pediatric hospitals: a neglected part of the hand-foot-mouth disease transmission chain in China? Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:524–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ940.

Wang J, Xiao Y, Cheke RA. Modelling the effects of contaminated environments on HFMD infections in mainland China. Biosystems. 2016;140:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2015.12.001.

Ruan F, Yang T, Ma H, Jin Y, Song S, Fontaine RE, et al. Risk factors for hand, foot, and mouth disease and herpangina and the preventive effect of hand-washing. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e898–904. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1497.

Zhang D, Li Z, Zhang W, Guo P, Ma Z, Chen Q, et al. Hand-washing: the main strategy for avoiding hand, foot and mouth disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060610.

Li P, Li T, Gu Q, Chen X, Li J, Chen X, et al. Children's caregivers and public playgrounds: potential reservoirs of infection of hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):36375. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36375.

Verstrepen WA, Kuhn S, Kockx MM, Van De Vyvere ME, Mertens AH. Rapid detection of enterovirus RNA in cerebrospinal fluid specimens with a novel single-tube real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(11):4093–6. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.39.11.4093-4096.2001.

Murase C, Akiyama M. Hand, foot, and mouth disease in an adult. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(14):e20. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMicm1713548.

Drago F, Ciccarese G, Broccolo F, Rebora A, Parodi A. Atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):e51–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.046.

Chen H, Huang W, Yang C, Su L, Zhang X, Meng J, et al. A preliminary study on adult HFMD close contacts. J Prev Med Inform. 2016;32:766–9.

Yu L, He J, Wang L, Yi H. Incidence, aetiology, and serotype spectrum analysis of adult hand, foot, and mouth disease patients: a retrospective observational cohort study in northern Zhejiang, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;85:28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2019.05.016.

Koh WM, Bogich T, Siegel K, Jin J, Chong EY, Tan CY, et al. The epidemiology of hand, foot and mouth disease in asia: a systematic review and analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(10):e285–300. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001242.

Chen SM, Du JW, Jin YM, Qiu L, Du ZH, Li DD, et al. Risk factors for severe hand-foot-mouth disease in children in Hainan, China, 2011-2012. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015; 27: 715–722. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515579123, 7.

Han Y, Wang Y, Mao Y, Wang S, Li J, Shen F, et al. Investigation on related factors of hand-foot-mouth disease in preschools institutions in Huangpu District of Shanghai occupation and health 2018; 34: 2244–2249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13329/j.cnki.zyyjk.2018.0583.

Guo N, Ma H, Deng J, Ma Y, Huang L, Guo R, et al. Effect of hand washing and personal hygiene on hand food mouth disease: a community intervention study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(51):e13144. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013144.

Mao YJ, Sun L, Xie JG, Yau KK. Epidemiological features and spatio-temporal clusters of hand-foot-mouth disease at town level in Fuyang, Anhui Province, China (2008-2013). Epidemiol Infect 2016; 144: 3184–3197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268816001710, 15.

Wang Y, Feng Z, Yang Y, Self S, Gao Y, Longini IM, Wakefield J, Zhang J, Wang L, Chen X, Yao L, Stanaway JD, Wang Z, Yang W Hand, foot, and mouth disease in China: patterns of spread and transmissibility. Epidemiology 2011; 22: 781–792. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e318231d67a, 6.

Xie YH, Chongsuvivatwong V, Tan Y, Tang Z, Sornsrivichai V, Mcneil EB. Important roles of public playgrounds in the transmission of hand, foot, and mouth disease. Epidemiol Infect 2015; 143: 1432–1441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268814002301, 7.

Xing N, Yang D, Xie J. Investigation of the influencing factors for hand-foot-and-mouth disease among preschool children in Hexi District of Tianjin. Modern Prev Med. 2014;41:1015–7.

Li E, Xu X, Zhou Z, Pan H. Risk factors of hand,foot and mouth disease in the scattered migrant children in Shanghai City. Pract Prev Med 2017; 24: 57–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-3110.2017.01.017.

Xiang L, Yuan G, Yang X, Jin K, Zhang Y, Wang J. Risk of enterovirus between hand foot and mouth disease among family members of infected and healthy children in Baoshan District of Shanghai. Chin J School Health 2018; 39: 1063–1065. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2018.07.030.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance offered by the National Mega Project on Major Infectious Disease Prevention, the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Program in sample collection, the Yonghe community health service center, Yongning Street, Zengcheng District, Guangzhou City,the Yuebei People’s Hospital of Shaoguan City and Shenzhen Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Mega Project on Major Infectious Disease Prevention (2017ZX10103011) and the Guangdong Provincial Science and Technology Program (2017A070713013). The funding had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL was in charge of coordination work of field epidemiology, the data-cleansing process, further data analysis laboratory experiments and manuscript drafting. JL, YC, PH and LG conducted the field investigation, the transportation of specimens and the questionnaire data entry. JL, PH, LG, CF, HP, DL and YH were responsible for repacking and refrigeration of specimens. QT, XH and ZM were the project partner, responsible for providing project implementation site and coordinating the fieldwork. CL, DW and XZ were the project partner, responsible for guiding and coordinating the laboratory work. DZ designed the research, supervised all aspects of the work and checked the manuscript. All authors re-examined and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In accordance with the guidelines for the protection of human subjects, ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the School of Public Health at Sun Yat-sen University (2019019). After learning the research subject matter and being promised to keep their personal information confidential, written informed consent was obtained from all caregivers and a parent or guardian for participants aged five years old or younger. Each participant could withdraw any time if they wanted to.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Chen, Y., Hu, P. et al. Caregivers: the potential infection resources for the sustaining epidemic of hand, foot, and mouth disease/herpangina in Guangdong, China?. Arch Public Health 79, 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00574-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-021-00574-8