Abstract

This work explores the new exact solutions of nonlinear fractional partial differential equations (FPDEs). The solutions are obtained by adopting an effective technique, the first integral method (FIM). The Riemann–Liouville (R–L) derivative and conformable derivative definitions are used to deal with fractional terms in FPDEs. The proposed method is applied to get exact solutions for space-time fractional Cahn–Allen equation and coupled space-time fractional (Drinfeld’s Sokolov–Wilson system) DSW system. The suggested technique is easily applicable and effectual, which can be implemented successfully to obtain the solutions for different types of nonlinear FPDEs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fractional Calculus (FC) is an imperative field of science which deals with real number powers of the differential equations. FC has numerous applications in science, for instance, in electromagnetics, fluid mechanics, biological models, optics, and signal processing. Aforementioned physical phenomena are accurately modeled by nonlinear FPDEs [1, 2]. FPDEs have gained a great significance and popularity over the last few years for their powerful potential applications, mainly in mathematical physics, biology, and engineering [3,4,5]. Recently, researchers are taking interest to investigate the exact solutions of nonlinear FPDEs [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Many effective methods have been introduced in order to acquire exact solutions of nonlinear FPDEs such as hyperbolic function method [12], extended hyperbolic tangent method [13,14,15,16], the sub-equation method [17], homotopy perturbation technique [18], exponential rational function method [19], and homotopy analysis method [20].

The FIM was first introduced by Feng for the solution of Burgers–KdV equation [21]. The FIM is based on commutative algebra ring theory. The FIM constructs the first integrals having explicit polynomial coefficients to an independent planar system using division theorem. The FIM, due to its reliability and efficacy, is eminently used by many researchers to interpret results for various kinds of nonlinear problems [21,22,23]. In contrast with different methods, the proposed technique has many advantages. The FIM avoids complex and tedious computations and provides exact and explicit solutions. Guner et al. applied the FIM to a fractional Cahn–Allen equation using Jumarie’s definition [24]. Therefore, in this work, the FIM is adopted to obtain exact solutions of the nonlinear space-time fractional Cahn–Allen equation and a coupled space-time fractional DSW system. Two definitions of fractional derivatives are applied: R–L derivative [4] and conformable derivative [25]. The R–L derivative is chosen as it is more general than the Caputo derivative.

The paper is arranged as follows. The basic definitions, properties, and theorems of R–L and a new conformable derivative are provided in Sect. 2. Section 3 illustrates the main steps of FIM. Afterwards, in Sect. 4, the exact solutions of fractional Cahn–Allen equation and fractional DSW system are given. Finally, Sect. 5 comprises conclusions and recommendations.

2 Preliminaries

Riemann–Liouville introduced the following definition [4]:

Definition

Let there be a continuous function g such that \(g:R\rightarrow R\), \(t\rightarrow g(t)\). The R–L derivative of fractional order α is expressed as follows:

From the above definition (1), we have

Recently, Khalil et al. presented a new simple definition of derivative of fractional order which is called conformable fractional derivative [25].

Definition

Let \(g:[0,\infty)\rightarrow R\) be a function, then it is a fractional conformable derivative of order α and can be presented as follows:

where \(\alpha\in(0,1)\) and holds for all \(x>0\). If the function g is α-differentiable in \((0, l)\) for \(l>0\) and further \(\lim_{x\rightarrow0^{+}}g^{(\alpha)}(x)\) exists, then the conformable derivative at 0 is defined as \(g^{(\alpha)}(0)=\lim_{x\rightarrow 0^{+}}g^{(\alpha)}(x)\).

Conformable integral of function g is defined as

where \(l\geq0\), and \(\alpha\in(0,1]\). Equation (4) represents the usual Riemann improper integral.

According to the definition in Eq. (3), Khalil et al. presented the following theorem [25], which provides some useful properties satisfied by the conformable derivative.

Theorem

Suppose the functions u and v are α-differentiable at any point \(x>0\) for \(\alpha\in(0,1]\). Then

-

(1)

\(T_{\alpha}(au+bv)=aT_{\alpha}(u)+bT_{\alpha}(v)\) \(\forall a,b\in \mathbb{R}\).

-

(2)

\(T_{\alpha}(x^{m})=mx^{m-\alpha}\) \(\forall m\in\mathbb{R}\).

-

(3)

\(T_{\alpha}(C)=0\) \(\forall u(x)=C\) (constant functions).

-

(4)

\(T_{\alpha}(uv)=uT_{\alpha}(v)+vT_{\alpha}(u)\).

-

(5)

\(T_{\alpha}(\frac{u}{v})=\frac{vT_{\alpha}(u)-uT_{\alpha }(v)}{v^{2}}\).

-

(6)

Additionally, if the function u is differentiable, then \(T_{\alpha }(u)(x)=x^{1-\alpha}\frac{du}{dx}\).

The new definition has gained significant attention due to its simplicity. Abdeljawad [26] used the conformable derivative to express chain rule, integration by parts, exponential functions, Taylor power series expansion, Gronwall’s inequality, and Laplace transform. Conformable time-scale calculus was introduced by Benkhettoua et al. [27]. Many scientists used this new derivative in some physical applications due to its convenience, simplicity, and usefulness [28,29,30]. Chung [31] discussed conformable Newtonian mechanics using this new definition. Hammad and Khalil [32] interpreted the results for the conformable heat equation.

3 The first integral method

A brief exposition of the FIM is presented as follows.

Step 1: First, we take into account a nonlinear FPDE of the following form:

Step 2: Then, the following transformation is applied:

In order to apply the R–L derivative, we have

In order to use a conformable derivative, we have

Using these transformations given in Eq. (7) and Eq. (8), we reduce the FPDE into an integer order nonlinear ODE as follows:

where \(U'(\xi)=\frac{dU(\xi)}{d\xi}\) and ξ is a new transformed variable.

Step 3: Afterwards, introducing some new independent variables, we get

A new system of nonlinear ODE is generated which is given as follows:

Step 4: According to the qualitative theory of ODEs, the general solutions of Eq. (11) can be directly obtained if one can find integrals of Eq. (11). Generally it is difficult to obtain even one first integral, because there is no systematic or logical procedure to find first integrals for a plane independent system. Division theorem presents an idea to find first integrals. One first integral of Eq. (11) is obtained by applying the division theorem, which reduces a nonlinear ODE to an integrable first order ODE. Finally, we obtain exact solutions of the problem after solving the system.

The division theorem is stated below which is defined in \(\mathbb{C}\) for two variables.

Division Theorem

([21])

Assume there are two polynomials \({P}(x,y)\) and \({Q}(x,y)\) in a complex domain \(\mathbb{C}(x,y)\) such that \({P}(x,y)\) is an irreducible polynomial in \(\mathbb{C}(x,y)\). If at all the zero points of \({P}(x,y)\) the polynomial \({Q}(x,y)\) vanishes, then a polynomial \({R}(x,y)\) exists in \(\mathbb{C}(x,y)\) and the following equality holds:

4 Applications

This section contains exact solutions of the considered models of fractional order.

4.1 Exact solutions of the space-time fractional Cahn–Allen equation

Cahn–Allen equation appears in numerous applications of science including quantum mechanics, mathematical biology, and plasma physics [33].

Consider the Cahn–Allen equation fractional in space and time

where \(\alpha\in(0,1)\). Firstly, we apply the R–L definition of fractional derivative. The following transformation is introduced:

where ξ is the transformation variable and k, c are the constants. Using Eq. (14) in Eq. (13), we convert our problem into an ODE:

Then using Eq. (10), the 2-D autonomous system is attained

Now, to find the first integral of Eqs. (16a)–(16b), we implement the division theorem. In accordance with the FIM, it is assumed that nontrivial solutions of the above system (cf. Eqs. (16a)–(16b)) are X and Y respectively. Thus, irreducible polynomial \(Q(X,Y)= \sum_{j=0}^{n}a_{j}(X)Y^{j}\) exists in \(\mathbb {C}[X,Y]\) and the following holds:

for \(j=0,1,\ldots,n\), and \(a_{n}(X)\neq0\). Now a polynomial \(r(X)+s(X)Y\) exists in \(\mathbb{C}[X,Y]\), so

Suppose \(n=1\). On equating coefficients of \(Y^{j}\) (\(j=0,1\)) in Eq. (18) on both sides, we get

As \(a_{j}(X)\) are polynomials of X, then from Eq. (19) we come to know that the polynomial \(a_{1}(X)\) is constant in nature, therefore \(s(X)=0\). Let us consider \(a_{1}(X)=1\), for convenience. After substituting afore values, we balance the degrees of the functions \(r(X)\) and \(a_{0}(X)\) and deduce the \(\operatorname{deg}(r(X))\) equal to 0 or 1. Assume that \(r(X)=A_{1}X+A_{0}\), therefore Eq. (20) gives

Here, B is the integration constant.

Replacing the values of \(a_{0}\), \(a_{1}\), r, and s in Eq. (21), we obtain a nonlinear system of algebraic equations by putting all coefficients equal to zero for the same powers of X. After calculations, we get:

Case 1:

Applying the conditions given in Eq. (23) and Eq. (22) in Eq. (17), we have

Combining Eq. (24) with Eq. (16a), the solution of fractional Cahn–Allen equation with R–L derivative is obtained as follows:

Case 2:

Applying the conditions given in Eq. (26) and Eq. (22) in Eq. (17), we have

Combining Eq. (27) with Eq. (16a), the solution of fractional Cahn–Allen equation with R–L derivative is obtained as follows:

Case 3:

Using the conditions given in Eq. (29) and Eq. (22) in Eq. (17), we have

Combining Eq. (30) with Eq. (16a), the solution of fractional Cahn–Allen equation with R–L derivative is obtained as follows:

Case 4:

Using the conditions given in Eq. (32) and Eq. (22) in Eq. (17), we have

Combining Eq. (33) with Eq. (16a), the solution of fractional Cahn–Allen equation with R–L derivative is obtained as follows:

Now we apply the conformable definition of fractional derivative. The following transformation is introduced:

where ξ is the transformation variable and k, c are the constants. Afterwards, applying the same procedure given from Eq. (15) to Eq. (22), we get four different solutions:

Case 1: For \(A_{1}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{k}\), \(A_{0}=\frac{\sqrt {2}}{k}\), \(B=0\), \(c=\frac{3k\sqrt{2}}{2}\), \(k=k\),

Case 2: For \(A_{1}=\frac{\sqrt{2}}{k}\), \(A_{0}=-\frac{\sqrt {2}}{k}\), \(B=0\), \(c=-\frac{3k\sqrt{2}}{2}\), \(k=k\),

Case 3: For \(A_{1}=-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{k}\), \(A_{0}=\frac{\sqrt {2}}{k}\), \(B=0\), \(c=\frac{3k\sqrt{2}}{2}\), \(k=k\),

Case 4: For \(A_{1}=-\frac{\sqrt{2}}{k}\), \(A_{0}=-\frac{\sqrt {2}}{k}\), \(B=0\), \(c=-\frac{3k\sqrt{2}}{2}\), \(k=k\),

It is important to note that the solutions \(u_{1}\), \(u_{2}\), \(u_{3}\), \(u_{4}\) are acquired by using the R–L derivative and \(u_{5}\), \(u_{6}\), \(u_{7}\), \(u_{8}\) are obtained by using the conformable derivative.

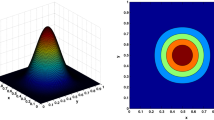

In Figs. 1–4, graphs of exact solutions of fractional Cahn–Allen equation are presented by using the R–L and conformable derivatives.

Figure 5 shows the effects of α on solutions \(u_{5}(x,t)\) using the conformable definition. Figure 5 reveals that the steeper peaks are originating from origin for smaller values of α, whereas wider peaks are found for values of α closer to 1.

4.2 Exact solutions of the space-time fractional Drinfeld’s Sokolov–Wilson system

One of the widely used models is a DSW system introduced by Drinfeld, Sokolov, and Wilson. Zha and Zhi [34] solved this system using an improved F-expansion method. Inc utilized the Adomian decomposition method to find solutions of the DSW system [35]. The solitary solution of this model was obtained by Zhang using variational approach [36].

Consider the space-time fractional DSW system [37]

In Eqs. (40a)–(40b), α is the order of the fractional derivative and \(\alpha\in(0,1)\).

Firstly, we apply the R–L definition of fractional derivative. The following transformation is introduced:

where ξ is the transformation variable and k, c are the constants. Using Eq. (41) into Eqs. (40a)–(40b), we convert the problem into ODE:

Considering Eq. (42a) and rearranging,

Integrating Eq. (43) w.r.t ξ and taking integration constant to be equal to zero, we get

Embedding Eq. (43) and Eq. (44) into Eq. (42b), we get a nonlinear ODE:

Integrating Eq. (45) with respect to ξ and taking integration constant equal to zero, we arrive at the following ODE:

Then using Eq. (10), the 2-D autonomous system is attained

Now, to find the first integral of Eqs. (47a)–(47b), we implement the division theorem. In accordance with the FIM, it is assumed that nontrivial solutions of the above system (cf. Eqs. (47a)–(47b)) are X and Y respectively. Thus, the irreducible polynomial \(Q(X,Y)= \sum_{j=0}^{n}a_{j}(X)Y^{j}\) exists in \(\mathbb {C}[X,Y]\) and the following holds:

for \(j=0,1,\ldots,n\), and \(a_{n}(X)\neq0\). Now, a polynomial \(r(X)+s(X)Y\) exists in \(\mathbb{C}[X,Y]\), so

Suppose \(n=1\). On equating coefficients of \(Y^{j}\) (\(j=0,1\)) in Eq. (49) on both sides, we get

As \(a_{j}(X)\) are polynomials of X, then from Eq. (50) we come to know that the polynomial \(a_{1}(X)\) is constant in nature, therefore \(s(X)=0\). Let us consider \(a_{1}(X)=1\), for convenience. After substituting these values, we balance the degrees of the functions \(r(X)\) and \(a_{0}(X)\) and deduce the \(\operatorname{deg}(r(X))\) equal to 0 or 1. Assume that \(r(X)=A_{1}X+A_{0}\), therefore Eq. (51) gives

Here, B is the integration constant.

Replacing the values of \(a_{0}\), \(a_{1}\), r, and s in Eq. (52), we get a nonlinear system of algebraic equations by putting all coefficients equal to zero for the same powers of X. After some calculations, we get

Applying the conditions given in Eq. (54) and Eq. (53) in Eq. (48), we have

Combining Eq. (55) with Eq. (47a), the solutions of fractional DSW system with R–L derivative are obtained as follows:

Now we apply the conformable definition of fractional derivative. The following transformation is introduced:

where ξ is the transformation variable and k, c are the constants. Afterwards, adopting the same procedure given in Eqs. (42a)–(42b) to Eq. (53), we get two different solutions:

It is important to note that the solutions \(u_{1}\), \(v_{1}\) are acquired by using the R–L derivative and \(u_{2}\), \(v_{2}\) are obtained by using the conformable derivative.

In Figs. 6–7, graphs of exact solutions of fractional DSW system are shown by using the R–L and conformable derivatives.

Figure 8 shows the effects of α on the solution \(v_{1}(x,t)\) using the R–L definition. Figure 8 depicts that the curved nonlinearity is observed for smaller values of α, whereas less nonlinear trends are found for α closer to 1.

5 Conclusion

The focus of the paper was to find exact solutions of FPDEs using two fractional derivatives. The FIM was used to find new exact solutions of nonlinear FPDEs, namely, a space-time fractional Cahn–Allen equation and a coupled space-time fractional DSW system. The R–L derivative and conformable derivative definitions were used to deal with the fractional terms in FPDEs. The suggested technique proved itself direct and concise. The FIM performs tedious and complicated algebraic calculations easily using a computer. Based on its good performance, we deduce that this technique is very effective to deal with various nonlinear fractional order systems.

References

Carvalho, A.R., Pinto, C.M., Baleanu, D.: HIV/HCV coinfection model: a fractional-order perspective for the effect of the HIV viral load. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 2 (2018)

Singh, J., Kumar, D., Baleanu, D.: On the analysis of fractional diabetes model with exponential law. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 231 (2018)

Kilbas, A.A., Srivastava, H.M., Trujillo, J.J.: Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations. North-Holland Mathematics Studies. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2006)

Miller, K.S., Ross, B.: An Introduction to the Fractional Calculus and Fractional Differential Equations. Wiley, New York (1993)

Podlubny, I.: Fractional Differential Equations: An Introduction to Fractional Derivatives, Fractional Differential Equations, to Methods of Their Solution and Some of Their Applications. Academic Press, San Diego (1998)

Polyanin, A.D., Zhurov, A.I.: Exact separable solutions of delay reaction–diffusion equations and other nonlinear partial functional–differential equations. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 19(3), 409–416 (2014)

Zhai, C., Jiang, R.: Unique solutions for a new coupled system of fractional differential equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-017-1452-3

Agarwal, R.P., Ahmad, B., Garout, D., Alsaedi, A.: Existence results for coupled nonlinear fractional differential equations equipped with nonlocal coupled flux and multi-point boundary conditions. Chaos Solitons Fractals 102, 149–161 (2017)

Zheng, B., Wen, C.: Exact solutions for fractional partial differential equations by a new fractional sub-equation method. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2013, 199 (2013)

Lu, D., Seadawy, A.R., Khater, M.: Structure of solitary wave solutions of the nonlinear complex fractional generalized Zakharov dynamical system. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 266 (2018)

Gepreel, K.A.: Explicit Jacobi elliptic exact solutions for nonlinear partial fractional differential equations. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2014, 286 (2014)

Xia, T.C., Li, B., Zhang, H.Q.: New explicit and exact solutions for the Nizhnik–Novikov–Vesselov equation. Appl. Math. E-Notes 1, 139–142 (2001)

El-Wakil, S.A., Abdou, M.A.: New exact travelling wave solutions using modified extended tanh-function method. Chaos Solitons Fractals 31(4), 840–852 (2007)

Fan, E.: Extended tanh-function method and its applications to nonlinear equations. Phys. Lett. 277(4), 212–218 (2000)

Wazwaz, A.M.: The tanh method: solitons and periodic solutions for the Dodd–Bullough–Mikhailov and the Tzitzeica–Dodd–Bullough equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 25(1), 55–63 (2005)

Ma, W.X., Fuchssteiner, B.: Explicit and exact solutions to a Kolmogorov–Petrovskii–Piskunov equation. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 31(3), 329–338 (1996)

Zhang, S., Zhang, H.Q.: Fractional sub-equation method and its applications to nonlinear fractional PDEs. Phys. Lett. 375(7), 1069–1073 (2011)

Momani, S., Odibat, Z.: Homotopy perturbation method for nonlinear partial differential equations of fractional order. Phys. Lett. 365(5), 345–350 (2007)

Aksoy, E., Kaplan, M., Bekir, A.: Exponential rational function method for space-time fractional differential equations. Waves Random Complex Media 26(2), 142–151 (2016)

Dehghan, M., Manafian, J., Saadatmandi, A.: Solving nonlinear fractional partial differential equations using the homotopy analysis method. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 26(2), 448–479 (2010)

Feng, Z.: On explicit exact solutions to the compound Burgers–KdV equation. Phys. Lett. 293(1), 57–66 (2002)

Bekir, A., Unsal, O.: Analytic treatment of nonlinear evolution equations using first integral method. Pramana 79(1), 3–17 (2012)

Bekir, A., Guner, O., Unsal, O.: The first integral method for exact solutions of nonlinear fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 10(2), 021020 (2015)

Guner, O., Ahmet, B., Cevikel, A.C.: A variety of exact solutions for the time fractional Cahn–Allen equation. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 130(7), 146 (2015)

Khalil, R., Al Horani, M., Yousef, A., Sababheh, M.: A new definition of fractional derivative. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 264, 65–70 (2014)

Abdeljawad, T.: On conformable fractional calculus. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 279, 57–66 (2015)

Benkhettou, N., Hassani, S., Torres, D.F.: A conformable fractional calculus on arbitrary time scales. J. King Saud Univ., Sci. 28(1), 93–98 (2016)

Atangana, A., Baleanu, D., Alsaedi, A.: New properties of conformable derivative. Open Math. 13(1), 889–898 (2015)

Eslami, M., Rezazadeh, H.: The first integral method for Wu–Zhang system with conformable time-fractional derivative. Calcolo 53(3), 475–485 (2016)

Cenesiz, Y., Kurt, A.: The new solution of time fractional wave equation with conformable fractional derivative definition. J. New Theory 7, 79–85 (2015)

Chung, W.S.: Fractional Newton mechanics with conformable fractional derivative. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 290, 150–158 (2015)

Hammad, M.A., Khalil, R.: Conformable fractional heat differential equation. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 94, 215–221 (2014)

Tascan, F., Bekir, A.: Travelling wave solutions of the Cahn–Allen equation by using first integral method. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 207(1), 279–282 (2009)

Xue-Qin, Z., Hong-Yan, Z.: An improved F-expansion method and its application to coupled Drinfeld–Sokolov–Wilson equation. Commun. Theor. Phys. 50(2), 309 (2008)

Inc, M.: On numerical doubly periodic wave solutions of the coupled Drinfeld’s Sokolov–Wilson equation by the decomposition method. Appl. Math. Comput. 172(1), 421–430 (2006)

Zhang, W.M.: Solitary solutions and singular periodic solutions of the Drinfeld–Sokolov–Wilson equation by variational approach. Appl. Math. Sci. 5(38), 1887–1894 (2011)

Shehata, A.R., Kamal, E.M., Kareem, H.A.: Solutions of the space-time fractional of some nonlinear systems of partial differential equations using modified Kudryashov method. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 101(4), 477–487 (2015)

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the anonymous reviewers for improving this manuscript. The authors gratefully acknowledge Mr. Muhammad Asif Javed for helping in grammatical and stylistic editing of the article.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Javeed, S., Saif, S. & Baleanu, D. New exact solutions of fractional Cahn–Allen equation and fractional DSW system. Adv Differ Equ 2018, 459 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1913-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1913-3