Abstract

A discrete tuberculosis model with direct progression and treatment of latently infected individuals is presented. The model does not consider the drug-resistant TB, and it assumes that latently infected individuals develop the active disease only because of being endogenous reactive, and a small fraction of infected individuals is assumed to develop the active disease soon after infection. The global stability of a disease-free equilibrium, the persistence of system, and the local stability of endemic equilibrium are discussed. The basic reproductive numbers with different control measures are determined and analyzed, and we give the critical value of probability of successful detection and treatment of infectious individuals. If a treatment only of infectious individuals cannot control TB transmission, the treatment of latent TB individuals should be carried out, and we give the critical value of the probability of treatment of infectious individuals. Numerical simulations are done to demonstrate the complex dynamics of the model.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Differential equations and difference equations are widely applied in epidemiological modeling. They are two typical mathematical approaches for modeling infectious diseases. Since the theory and method for dynamical studies of differential equations have developed much more completely than those for difference equations, there are relatively few difference equations in epidemiological modeling compared with differential equations. In recent years, there were increasing interest and research results on discrete epidemic models [1–8]. The fact that the epidemiological data are usually collected in discrete time units, such as days, weeks or months, makes the discrete model a natural choice to describe a disease transmission. The straightforward recurrence relationship of the difference equation models is easier to understand, which is also a prominent advantage over the differential equation models. The direct comparison of the model results with the actual data provides us a fast and simple way to validate the model structure and parameter estimation. The fact that the discrete models exhibit a richer dynamical behavior than the continuous models brings about more challenging problems for researches, and more interesting results can be obtained. For example, the simple logistic model, \(x_{n+1}=rx_{n}(1-x_{n}/K)\), the Ricker model \(x_{n+1}=x_{n}e^{r-x_{n}/K}\) [9–11], and the Hassell model, \(x_{n+1}=\lambda x_{n}(1+a x_{n})^{-b}\) [12] exhibit a rich dynamical behavior.

There have been increasing interest and more studies on the discrete time epidemic models recently. Various discrete epidemic models have been successfully applied to describe the infectious disease transmission, such as SARS, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS [13–18]. The theoretical study of discrete epidemic models focuses on the computation of the basic reproduction number [19–21], the existence and the global stability of the disease-free equilibrium [4, 5, 14–16], the existence and the local stability of the endemic equilibrium [22, 23], and the persistence of the disease [14, 15]. Attention has also be paid to various bifurcations of the discrete epidemic models, the equilibrium bifurcation [3, 21, 24–26], the transcritical bifurcation, the flip bifurcation, the saddle-node bifurcation, the Hopf bifurcation, and the bifurcation to chaos [3–5].

There also have been many researches studying mathematical models of the transmission dynamics of TB in human populations. Those researches include slow and fast progression, a variable latent period, MDR TB, multiple strains, exogenous reinfection, generalized households, co-infection with HIV, and the control strategy for TB [27–35]. However, there are a few papers using discrete mathematical models to study the treatment of latent TB as a TB control strategy [3, 36, 37]. The treatment of latent tuberculosis infection is essential to controlling and eliminating TB, because it substantially reduces the risk from latent TB to active TB cases. In this paper, we use the discrete models with direct progression and treatment of latently infected individuals to analyze the impact of the treatment of latently infected individuals on TB transmission.

Our discrete model with treatment of latent TB individuals is presented in the next section. The positivity of solutions is also discussed. The global stability of the disease-free equilibrium and the persistence of the system is discussed in Section 3. The stability of endemic equilibrium is proved in Section 4. The effect of two treatment strategies is studied in Section 5. Numerical simulations are done on the basis of the TB infection data in China to show the effect of treatment strategies. The last section includes concluding remarks and discussions.

2 The discrete TB model

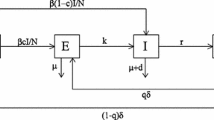

TB is an airborne infectious disease transmitting from person to person via droplets with TB bacilli. After being infected, most people become latently infectious, with the bacteria being alive in the body but inactive. Latently infectious individuals do not have symptoms and cannot spread the infection to others. Most people are able to fight the infection with their immune system, but those people with latent infection are at risk of developing the active disease. Based on these characteristics, there have been many continuous models to be used to describe TB transmission. Here, we will build the discrete mathematical model for TB transmission which considers the direct progression, chemoprophylaxis for the latent individuals, and treatment of the infectious individuals.

The total population is epidemiologically divided into susceptible, latent, and infectious classes. Let \(S(t)\) be the number of susceptible individuals at time t, \(L(t)\) be the number of latent individuals, and \(I(t)\) be the number of infectious individuals. \(N(t)=S(t)+L(t)+I(t)\) is the total population size. We assume that individuals recovered by successful treatment do not acquire immunity, and they will become member of the susceptible compartment. Hence our model is of SLIS type.

Susceptible individuals may get infected and enter the latent compartment. The surviving latent individuals will experience one of the two mutually exclusive events to leave the latent compartment, naturally progressing into infectious class, or receiving the treatment. These two events happen randomly. The probabilities for receiving the treatment is m, and \(1-m\) is the probabilities for natural progression. Our model framework takes the following form:

where Λ is the recruitment rate into the population, p the survival probability; k is the conditional probability that a latent individual is treated successfully given that the individual receives the treatment, and it should rely on the capability of finding latent individuals and budgetary issues. α is the probability that a latent individual becomes an infectious individual that the natural progression happens; γ the probability that an infectious individual recovers successfully; \(1-\frac{\beta I(t)}{N(t)}\) is for the probability of not becoming infected, where β characterizes the disease transmission probability, satisfying \(0<\beta<1\); q is the probability that the infected ones enter the latent compartment, accordingly, \(1-q\) is the probability that the infected ones enter the infectious compartment by the fast development; all parameters are positive and less than one.

Based on biological considerations, system (1) will be studied in the following region:

In the following, we first discuss the positivity and boundedness of solutions for system (1). The following theorem holds.

Theorem 2.1

The solutions \(S(t)\), \(L(t)\), and \(I(t)\) of system (1) with initial value \(S(0)=S_{0}\geq0\), \(L(0)=L_{0}\geq0\), and \(I(0)=I_{0}\geq0\), respectively, are non-negative for all \(t\geq0\), \(t\in N\). For the system (1), the region Ω is positively invariant and all solutions starting in the Ω approach, enter, or stay in Ω.

Proof

Let \(S(0)=S_{0}\geq0\), \(L(0)=L_{0}\geq0\), and \(I(0)=I_{0}\geq0\), by using (1), we have

Because of \(0\leq I(t)\leq N(t)\) for any \(t\geq0\), \(t\in N\), \(0\leq\beta \leq1\), we know that \(1-\frac{\beta I_{0}}{N_{0}}\geq0\). It implies that \(S(1)>0\). In addition, \(0<\alpha<1\), \(0< k<1\), and \(0< m<1\) illustrate \(L(1)\geq0\). Furthermore, \(0<\gamma<1\) implies that \(I(1)\geq0\) holds. The recurrent procedure implies that \(S(t)>0\), \(L(t)\geq0\), \(I(t)\geq0\) for all \(t\geq0\), \(t\in N\). The solutions of (1) are non-negative.

By using \(N(t)=S(t)+L(t)+I(t)\), we know \(N(t)\) satisfies

The fact \(0< p<1\) and the last equation in (2) implies that \(N^{*}=\frac{\Lambda}{1-p}\) is the unique equilibrium of (2), and \(N^{*}\) is globally asymptotically stable, i.e., for any solution \(N(t)\) of (2) with positive initial value \(N(0)\), \(\lim_{t\rightarrow\infty}N(t)=N^{*}\) holds. It implies that \(N(t)\) is bounded and all solutions starting in the region Ω approach, enter or stay in Ω. □

Using the limiting equations and \(S(t)=N^{*}-L(t)-I(t)\), we reduce the three dimensional system (1) into two dimensional ones:

In the following, we will study the dynamical behavior of model (3) since model (3) exhibits the same qualitative dynamics as those of system (1) [38]. It is clear that the positively invariant of system (3) is

Applying the approach in [39] to our model, we can obtain the basic reproductive number of model (3):

The basic reproductive number \(R_{0}\) is defined mathematically as the spectral radius of the next generation matrix in [39]; in fact, each term in \(R_{0}\) has a clear epidemiological interpretation. \(1/ (1-p(1-\gamma) )\) is the average infection period. \((1-m)p\alpha/ (1-p(1-km)+p\alpha(1-m) )\) is the proportion of latent individuals that become infectious by natural progression. \(p\beta/ (1-p(1-\gamma) )\) is the average of new cases generated by a typical infectious member in the entire infection period, where \(qp\beta/ (1-p(1-\gamma) )\) is the average of new cases generated by a typical infectious member who enters the infectious compartment by natural progression in the entire infection period, \((1-q)p\beta/ (1-p(1-\gamma) )\) is the average of new cases generated by a typical infectious member who enters the infectious compartment by direct progression in the entire infection period.

3 The extinction and persistence for the disease

By directly calculating model (3), we know there exists the disease-free equilibrium \(P_{0}^{*}=(L_{0}^{*},I_{0}^{*})=(0,0)\) when \(R_{0}<1\), and there is an endemic equilibrium \(P_{1}^{*}=(L_{1}^{*},I_{1}^{*})\) when \(R_{0}>1\), where

In the following, we will use the linearization matrix to discuss the local stability of equilibrium. The Jacobian matrix of model (3) at equilibrium \(P^{*}\) is

3.1 The extinction for the disease

Theorem 3.1

If \(R_{0}<1\), then the disease-free equilibrium \(P_{0}^{*}\) of model (3) is globally asymptotically stable; if \(R_{0}>1\), then \(P_{0}^{*}\) is unstable.

Proof

When \(R_{0}<1\), we have \(P^{*}=P_{0}^{*}\), and

We denote

It is clear that

Since \(R_{0}<1\), we have \(\frac{(1-m)p\alpha\times qp\beta}{ (1-p(1-km)+p\alpha(1-m) ) (1-p(1-\gamma) )}<1\). Furthermore, we obtain \((1-m)p\alpha qp\beta< (1-p(1-km)+p\alpha (1-m) ) (1-p(1-\gamma) )\). Therefore,

Similarly, \(R_{0}<1\) implies that \(\frac{(1-q)p\beta}{1-p(1-\gamma)}<1\). We obtain \((1-q)p\beta<1-p(1-\gamma)\). So, we have

which illustrates that \(f(0)<1\) as \(R_{0}<1\). By using of the Jury criterion, we know the disease-free equilibrium \(P_{0}^{*}\) is of local stability. If \(R_{0}>1\), we have \(f(1)<0\). The Jury criterion implies that the disease-free equilibrium \(P_{0}^{*}\) is unstable. □

In the following, we use the Lyapunov function to prove the globally asymptotically stability of \(P_{0}^{*}\). We define \(F:[0, N^{*}]\times[0, N^{*}]\rightarrow[0, N^{*}]\times[0, N^{*}]\) by

Obviously, F is the mapping derived by system (3), and \((0, 0)\) is a fixed point of F. The linear function

on \([0, N^{*}]\times[0, N^{*}]\) is continuous and positive definite with respect to \((0, 0)\). Therefore, V is a Lyapunov function on the domain of F. For any \((L, I)\in[0, N^{*}]\times[0, N^{*}]\),

Hence, if \(R_{0}<1\), then \(\Delta V(L, I)<0\) holds for \((L, I)\in[0, N^{*}]\times[0, N^{*}]\). It follows from Theorem 4.22 in [40] that \(P_{0}^{*}\) is globally asymptotically stable.

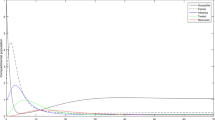

We illustrate our theoretical results on disease extinction by numerical simulation. Taking \(\Lambda=10\), \(p=0.994\), \(q=0.95\), \(\beta=0.3\), \(\alpha=0.003\), \(m=0.001\), \(k=0.001\), and \(\gamma=0.2\), we obtain \(R_{0}=0.5298<1\), and the disease-free equilibrium \(P_{0}^{*}=(0, 0)\) is globally asymptotically stable. The solution curves of the latently infected individuals \(L(t)\) and the infectious individuals \(I(t)\) are given in Figure 1(a) and (b), respectively. The initial values at \(t=0\) are \((100, 1)\), \((70, 1.5)\), and \((40, 2)\), respectively. We observe that solutions with positive initial values will converge to the disease-free equilibrium \(P_{0}^{*}\).

The global stability of disease-free equilibrium \(\pmb{P_{0}^{*}}\) of model ( 3 ) as \(\pmb{R_{0}<1}\) .

3.2 The persistence for the disease

Theorem 3.2

If \(R_{0}>1\), then the disease will have persistence in the population, i.e., there exists a positive ϵ, such that the solution of model (3) with the initial value \(L(0)>0\) and \(I(0)>0\) satisfies

Proof

We denote \(\mathcal{X}=\Omega\), \(\mathcal{X}_{0}=\{(L,I)\in\mathcal {X}\mid L>0, I>0\}\), and \(\partial\mathcal{X}_{0}=\mathcal{X}\backslash \mathcal{X}_{0}\). Let \(\Phi: \mathcal{X}\rightarrow\mathcal{X}\), \(\Phi_{t}(x_{0})=\phi (t,x_{0})\) be the solution map of model (3) with \(\phi(0, x_{0})=x_{0}\), and \(x_{0}= (L(0), I(0) )\).

Define \(\mathcal{M}=\{P_{0}^{*}\}\), and

It is clear that \(M_{\partial}=\{(0,0)\}\). Furthermore, there is exactly one fixed point \(P_{0}^{*}=(0,0)\) in \(M_{\partial}\). Because \(N^{*}\) is globally attractive in \(\partial X_{0}\) and due to Lemma 5.9 in [41], we know that no subset of \(\mathcal{M}\) forms a cycle in \(\partial \mathcal{X}_{0}\). The definition of \(M_{\partial}\) implies that \(M_{\partial}\) is the maximum positive invariant set in \(\partial\mathcal{X}_{0}\), that is, \(\Phi_{t}(M_{\partial})\subset M_{\partial}\). Therefore, \(\bigcup_{(L(0),I(0))\in M_{\partial}}=P_{0}^{*}\).

For any solutions \((L(t), I(t))\) of model (3) with initial value \((L(0),I(0) )\in\mathcal{X}_{0}\), we further claim that

If it is not true, there exists \(t_{1}>0\), \(t_{1}\in N\), such that \(L(t)\leq \epsilon\), \(I(t)\leq\epsilon\) for all \(t\geq t_{1}\), \(t\in N\). Let \(H(t)=L(t)+I(t)\), then \(H(t)\leq2\epsilon\), \(t\geq t_{1}\), \(t\in N\), and we have

Furthermore, we have

It is clear that the perturbed equation

or

\(R_{0}>1\) implies that \(p\beta+p(1-\gamma)>1\), namely, \(p\beta+p(1-\gamma )-\frac{p\beta\epsilon}{N^{*}}>1\) holds for a small \(\epsilon>0\). Therefore, \(H_{1}(t)\rightarrow\infty\) as \(t\rightarrow\infty\) and \(\epsilon\rightarrow0\). The comparison principle implies that \(H(t)\rightarrow\infty\) as \(t\rightarrow\infty\) and \(\epsilon\rightarrow0\). In fact, \(H(t)\leq2\epsilon\) for all \(t\geq t_{1}\), \(t\in N\), a contradiction. It implies that \(L(t)+I(t)\rightarrow\infty\), for all \(t\geq t_{1}\), \(t\in N\). On the other hand, \(0\leq L(t)\leq\epsilon\), \(0\leq I(t)\leq\epsilon\) for all \(t\geq t_{1}\), \(t\in N\). It implies that \(L(t)\rightarrow\infty\) and \(I(t)\rightarrow\infty\) at least established for all \(t\geq t_{1}\), \(t\in N\). There is a contradiction, that is, the conclusion in (4) holds.

Equation (4) implies that \(P^{*}_{0}\) is isolated in \(\mathcal {X}_{0}\), and \(W^{s}(P^{*}_{0})\cap\mathcal{X}_{0}=\emptyset\). In fact, \(P^{*}_{0}\) is also isolated in \(\partial\mathcal{X}_{0}\) because \(N^{*}\) is globally attractive in \(\partial\mathcal{X}_{0}\). Thus, \(P^{*}_{0}\) is isolated in \(\mathcal{X}\). From Theorem 1.3.1 and Remark 1.3.1 in [42], it follows that Φ is uniformly persistent with respect to \((\mathcal{X}_{0}, \partial\mathcal{X}_{0})\). Furthermore, Theorem 1.3.4 in [42] implies that the solutions of model (3) are uniformly persistent with respect to \((\mathcal{X}_{0}, \partial\mathcal{X}_{0})\) when \(R_{0}>1\). That is, there exists an \(\epsilon>0\), such that

□

4 The stability of the endemic equilibrium

Theorem 4.1

If \(R_{0}>1\), then the endemic equilibrium \(P_{1}^{*}\) of model (3) is locally asymptotically stable.

Proof

In the case where \(P^{*}=P_{1}^{*}\), we have

We denote

By directly calculating, we obtain

Rearranging the expression of \(g(-1)\), we have

where

\(a_{2}>0\) implies that the quadratic function curve opens upward. \(a_{0}<0\) implies that the quadratic function equation has two real roots, which are positive and negative, respectively. Because of \(a_{2}+a_{1}>0\), we obtain \(-\frac{a_{1}}{2a_{2}}<\frac{1}{2}\), which implies that the axis of symmetry of the quadratic function curve is on the left of \(R_{0}=1\). In addition,

with \(R_{0}=1\). Because of \(1-p(1-km)+p\alpha(1-m)>(1-m)p\alpha qp\beta\), and \(1+p(1-km)-p\alpha(1-m)=1+p(1-\alpha)(1-m)+p(1-k)m>1\), we obtain \(a_{2}R_{0}^{2}+a_{1}R_{0}+a_{0}>0\) as \(R_{0}=1\). Therefore, \(a_{2}R^{2}_{0}+a_{1}R_{0}+a_{0}>0\) as \(R_{0}>1\), that is, \(g(-1)>0\).

Similarly, we have

where

\(b_{2}>0\) implies that the quadratic function curve opens upward. \(b_{0}>0\) implies that the quadratic function equation has roots which are of the same sign. Because of \(b_{2}+b_{1}>0\), we obtain \(-\frac{b_{1}}{2b_{2}}<\frac{1}{2}\), which implies that the axis of symmetry of the quadratic function curve is on the left of \(R_{0}=1\). In addition, \(b_{2}R_{0}^{2}+b_{1}R_{0}+b_{0}>0\) as \(R_{0}=1\). Therefore, we obtain \(b_{2}R^{2}_{0}+b_{1}R_{0}+b_{0}>0\) as \(R_{0}>1\), that is, \(g(0)<1\). The Jury criterion implies that the endemic equilibrium \(P_{1}^{*}\) is locally stable as \(R_{0}>1\). □

The global stability of the endemic equilibrium of (3) is very difficult, though Theorems 3.2 and 4.1 established the persistence and local stability as \(R_{0}>1\). We investigate the global stability of the endemic equilibrium by numerical simulations. Taking \(\Lambda=10\), \(p=0.994\), \(q=0.95\), \(\beta=0.7\), \(\alpha=0.003\), \(m=0.001\), \(k=0.001\), and \(\gamma=0.2\), we obtain \(R_{0}=1.2363>1\). In this case, the numerical simulation shows that the endemic equilibrium \(P_{1}^{*}=(313.3017, 5.2621)\) may be globally asymptotically stable. The solution curves of the latently infected individuals \(L(t)\) and the infectious individuals \(I(t)\) are given in Figure 2(a) and (b), respectively. The initial values at \(t=0\) are \((310,5)\), \((313,5.3)\), and \((325,5.5)\), respectively. We observe that solutions with positive initial values will converge to the endemic equilibrium \(P_{1}^{*}\).

The global stability of the endemic equilibrium \(\pmb{P_{1}^{*}}\) of ( 3 ) as \(\pmb{R_{0}>1}\) .

We always assume that the parameter obeys \(0<\beta<1\) in theoretical discussions so as to guarantee the positivity of the solution of (3). In fact, if \(\beta>1\), and β is not large enough, the numerical simulation shows that solutions of (3) are still positive, and the endemic equilibrium \(P_{1}^{*}\) may lose the global stability and there exists chaos as β increases, which can lead to increasing \(R_{0}\) (see Figure 3). In Figure 3, we fix \(\Lambda=10\), \(p=0.994\), \(q=0.01\), \(\alpha=0.001\), \(m=0.01\), \(k=0.1\), \(\gamma=0.8\), and \(\beta\in[0.01, 6.00)\), furthermore, \(0< R_{0}<7.3701\). Figure 3 illustrates that one only has a disease-free equilibrium as \(R_{0}<1\), and an endemic equilibrium exists as \(1< R_{0}<6\). In addition, the endemic equilibrium loses the global stability as \(R_{0}>6\), and exhibits chaotic behavior.

5 Effect of control strategies

In our model, we consider the direct progression to active TB once one is infected, and both treatment of latently infected individuals and infectious individuals. By directly calculating, we obtain

The two equations of (5) illustrate that the basic reproductive number \(R_{0}\) decreases as the proportion of m and the probability k of successful detection and effective treatment of latently infected individuals. The treatment of latent tuberculosis infection contributes to slowing down TB transmission because it substantially reduces the risk that TB infection will progress to TB disease. Therefore, we consider both treatment of the latently infected individuals and for the infectious individuals. We assume that the word ‘control’ would mean bringing down the number of infectious TB cases.

To see the effect of these interventions, we need to consider the basic reproduction number of the model without treatment of the latent and infectious individuals. This is given by

\(R_{1}<1\) implies that TB will die out without any treatment. In fact, \(R_{1}>1\) is the usual case for the current TB epidemic in many countries. Taking China as an example, large scale national sampling surveys of TB epidemiology were carried out in 1979, 1984/85, 2000, and 2010, respectively. The 1979 and 2000 national surveys were more comprehensive and more information was obtained. The tuberculin skin test was done in those two sampling surveys. The result of those two surveys show that PPD (purified protein derivative) positive rates in 1979 and 2000 are 27.9% and 44.5%, respectively [43]. The 2010 national TB epidemiological survey shows that the prevalence of active TB cases in the population 15 years of age and older is 459 cases per 100,000, a little lower than the 466 cases per 100,000 in 2000. The estimated active TB prevalence in the Chinese population in 2010 is 392 cases per 100,000, a little higher than the 367 cases per 100,000 found in 2000 [44]. This information indicates that TB infection remains a serious public health challenge in China.

In China, the population recruitment mainly depends on births. Therefore, we use the average natural death from 2000-2009 as the natural death rate, namely, \(p=0.994\). It is estimated that about 5%-10% of latent TB infection will progress to TB disease [45]. We assume that the lifespan of the population is 75, then the age of the infected individual may be from 1 year old to 75 years old. The individuals may survive 1 year, 2 years, …, or 75 years after becoming TB latent. We choose the average survival time to be \(\frac{75}{2}\approx38\). The estimate of the annual progression rate from latent to infectious is \(\alpha\in[\frac{0.05}{38}, \frac{0.1}{38}]=[0.00132, 0.00263]\). We take \(q=0.99\), and \(\beta\in[0.1, 0.6]\) [46]. The numerical calculation shows that \(R_{1}>1\) (see Figure 4). In short, we always assume that \(R_{1}>1\) in this section.

In addition, as \(m\rightarrow0\), the system (3) reduces to a model in which there is no treatment of latent TB individuals. In this case, every TB infected individual leaves the latent compartment only by the natural progression and the reproductive number becomes

We first consider the effect of both treatment of latently infected individuals and for infectious individuals on control TB transmission. The difference between \(R_{1}\) and \(R_{0}\) is

It easy to see that \(\Delta_{1}>0\). It implies that both the treatment of latently infected individuals and for infectious individuals can lead to a decrease of the basic reproductive number. That is, treatment is effective at the population level so as to slow down the spread of TB, while having treatment of the individuals in the latent and the infectious compartment.

5.1 Effect of treatment of the infectious individuals

Because the latently TB infected individuals cannot infect others, one does not take to treatment of latently infected individuals in developing and undeveloped countries so as to save expense. Therefore, we only consider treatment of the TB infectious individuals. We will give the critical value \(\gamma^{*}\) of the probability γ of successful detection and treatment of infectious individuals so that the basic reproductive number of the model is less than one.

When \(m=0\) and \(\gamma>0\) (with only treatment for the infectious individuals), the basic reproductive number is \(R_{2}\). With the application of only treatment of the population in the infectious compartment, we can obtain the difference between \(R_{1}\) and \(R_{2}\):

\(\Delta_{2}>0\) implies that the treatment is effective at the population level so as to slow down the spread of TB, while having treatment of the individuals in the infectious compartment.

Using (6), we can calculate the critical values \(\gamma^{*}\) of the disease control parameters γ to have \(R_{2}<1\). Namely,

Rearranging (7), we can obtain

Equation (8) shows that the basic reproductive number \(R_{2}<1\), while the successful detection and effective treatment probability γ of infectious individuals is more than \(\gamma^{*}\). However, \(\gamma<\gamma^{*}\) will lead to \(R_{2}>1\), which implies that successful detection and effective treatment of infectious individuals is not enough, TB transmission will be in persistence. Therefore, we should strengthen the successful detection and effective treatment of infectious individuals so as to eradicate TB transmission in the population. Taking the same parameter values in Figure 4, the function of the basic reproductive number, \(R_{2}\), is shown in Figure 5 with \(m=0\) and for \(\gamma=0.05\), \(\gamma=0.1\), and \(\gamma=0.2\), respectively.

5.2 Effect of treatment of the latent individuals

When the probability γ of successful detection and treatment of infectious individuals does not reach the critical value \(\gamma^{*}\), we also take the treatment of latently TB individuals, and give the critical value \(m^{*}\) of the probability m of the treatment of latently individuals, so that \(R_{0}<1\).

In this case, we assume that \(\gamma<\gamma^{*}\), or \(R_{2}>1\). Similarly, we can obtain the difference between \(R_{2}\) and \(R_{0}\):

\(\Delta_{3}>0\) implies that the treatment is effective at the population level so as to slow down the spread of the disease, while having treatment of the individuals in the latent and the infectious compartment.

Using (9), we can calculate the critical values \(m^{*}\) of the disease control parameters m to have \(R_{0}<1\). Namely,

Rearranging (10), we can obtain

Because of \(R_{2}>1\), we obtain \(p\alpha qp\beta> (1-p(1-\alpha) ) (1-p(1-\gamma)-(1-q)p\beta )\). It is clear that \((1-p(1-\alpha) ) (1-p(1-\gamma)-(1-q)p\beta )> (p(1-k)-p(1-\alpha) ) ((1-q)p\beta-(1-p(1-\gamma)) )\), which implies \(m^{*}>0\). By (11), we know that if the effective treatment of the individuals in the infectious compartment satisfies \(0<\gamma<\gamma^{*}\), we should strengthen control measures so as to have \(R_{0}<1\). Therefore, we also take the treatment of latent TB individuals, and the probability for receiving the treatment m satisfies \(m>m^{*}\).

Taking the same parameter values in Figure 4, by calculating, we can obtain \(\gamma^{*}=(\frac{1}{p}-1) (R_{1}-1 )\in[0.0127, 0.1798]\), furthermore, we fix \(\gamma=0.01\), satisfying \(0<\gamma<\gamma^{*}\). In addition, taking \(k=0.9\), we use the same parameter values to obtain \(m^{*}\in[0.0015, 0.1391]\). The numerical method shows that \(R_{0}\) with \(\gamma=0.01\) and \(k=0.9\) for \(m=0.001\), \(m=0.01\), \(m=0.1\), and \(m=0.2\), respectively (see Figure 6). Figure 6 shows that, in the case where \(\gamma<\gamma^{*}\), we can control the probability \(m>m^{*}\) of the treatment of latent individuals, so that \(R_{0}<1\).

6 Conclusion and discussion

In this paper, we analyze a class of discrete SLIS models with direct progression and chemoprophylaxis for latent TB individuals. The basic reproductive numbers \(R_{0}\) with both treatment of latently infected individuals and infectious individuals are determined. Furthermore, we study the global stability of the disease-free equilibrium as \(R_{0}<1\), the persistence of the system, and the local stability of the endemic equilibrium as \(R_{0}>1\). The numerical simulation shows that when \(\beta>1\), and β is not large enough, the solutions of the model are still positive, and the endemic equilibrium may lose the stability and there exists chaos as β increases, which can lead to \(R_{0}\) increasing. By analyzing \(R_{0}\), we learn that the treatment of latent TB individuals contributes to a decrease of the basic reproductive number, namely, a reduction of the speed of TB transmission.

In addition, the basic reproductive number \(R_{1}\) without treatment, and the basic reproductive number \(R_{2}\) with treatment of infectious individuals are determined, respectively. We also discuss the effect of the treatment of the infectious individuals on TB transmission, and give the critical value \(\gamma^{*}\) of the probability γ of successful detection and treatment of infectious individuals so that the basic reproductive number of the model is \(R_{2}<1\). Once \(R_{2}>1\), that is, \(\gamma<\gamma^{*}\), we need to strengthen control measures so as to slow down the TB transmission. In this situation, we take both the treatment of latently infected individuals and infectious individuals, and give the critical value \(m^{*}\) of probability m of the treatment of latently infected individuals so that the basic reproductive number of the model obeys \(R_{0}<1\).

By using the TB data in China, we compare the effect of these different treatment strategies for the control of TB. The numerical simulations totally support our theoretical results. Moreover, our conclusions show that, if the probability γ of successful detection and treatment of infectious individuals cannot reach the critical value \(\gamma^{*}\), only treatment of infectious individuals cannot effectively control the TB transmission, which implies that we should strengthen control measures so as to slow down the TB transmission. That is, we should take both the treatment of latently infected individuals and of infectious individuals.

References

Allen, L: Some discrete-time SI, SIR, and SIS epidemic models. Math. Biosci. 124, 83-105 (1994)

Allen, L, Burgin, A: Comparison of deterministic and stochastic SIS and SIR models in discrete time. Math. Biosci. 163, 1-33 (2000)

Cao, H, Zhou, YC, Song, BJ: Complex dynamics of discrete SEIS models with simple demography. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2011, Article ID 653937 (2011). doi:10.1155/2011/653937

Castillo-Chavez, C, Yakubu, AA: Discrete-time SIS models with complex dynamics. Nonlinear Anal. TMA 47, 4753-4762 (2001)

Castillo-Chavez, C, Yakubu, AA: Discrete-time SIS models with simple and complex population dynamics. In: Castillo-Chavez, C, Blower, S, van den Driessche, P, Kirschner, D, Yakubu, AA (eds.) Mathematical Approaches for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases: An Introduction, pp. 153-163. Springer, New York (2002)

Franke, JE, Yakubu, AA: Discrete-time SIS epidemic model in a seasonal environment. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 66, 1563-1587 (2006)

Zhou, YC, Ma, ZE: Global stability of a class of discrete age-structured SIS models with immigration. Math. Biosci. Eng. 6, 409-425 (2009)

Zhou, YC, Paolo, F: Dynamics of a discrete age-structured SIS models. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst., Ser. B 4, 843-852 (2004)

May, RM: Biological population obeying difference equations: stable points, stable cycles, and chaos. J. Theor. Biol. 51, 511-524 (1975)

May, RM: Deterministic models with chaotic dynamics. Nature 256, 165-166 (1975)

May, RM: Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 261, 459-467 (1976)

Hassell, MP: Density dependence in single-species populations. J. Anim. Ecol. 44, 283-289 (1975)

Cao, H, Dou, ZH, Liu, X, Zhang, FJ, Zhou, YC, Ma, ZE: The impact of antiretroviral therapy on the basic reproductive number of HIV transmission. Math. Model. Appl. 1, 33-37 (2012)

Cao, H, Xiao, YN, Zhou, YC: The dynamics of a discrete SEIT model with age and infection-age structures. Int. J. Biomath. 5, 61-76 (2012)

Cao, H, Zhou, YC: The discrete age-structured SEIT model with application to tuberculosis transmission in China. Math. Comput. Model. 55, 385-395 (2012)

Zhou, YC, Cao, H: Discrete tuberculosis transmission models and their application. In: Sivaloganathan, SA (ed.) Survey of Mathematical Biology. Fields Communications Series, vol. 57, pp. 83-112. A co-publication of the AMS and Fields Institute, Canada (2010)

Zhou, YC, Khan, K, Feng, ZL, Wu, JH: Projection of tuberculosis incidence with increasing immigration trends. J. Theor. Biol. 254, 215-228 (2008)

Zhou, YC, Ma, ZE, Brauer, F: A discrete epidemic model for SARS transmission and control in China. Math. Comput. Model. 40, 1491-1506 (2004)

Allen, L, van den Driessche, P: The basic reproduction number in some discrete-time epidemic models. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 14, 1127-1147 (2008)

Cao, H, Zhou, YC: The basic reproduction number of discrete SIR and SEIS models with periodic parameters. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst., Ser. B 18, 37-56 (2013)

Li, X, Wang, W: A discrete epidemic model with stage structure. Chaos Solitons Fractals 26, 947-958 (2005)

Arreola, R, Crossa, A, Velasco, MC, Yakubu, AA: Discrete-time SEIS models with exogenous re-infection and dispersal between two patches. http://mtbi.asu.edu/files/0835_001.pdf (2000). Accessed 15 Apr 2015

Gonzalez, PA, Saenz, RA, Sanchez, BN, Castillo-Chavez, C, Yakubu, AA: Dispersal between two patches in a discrete time SEIS model. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/221711667_Dispersal_between_two_patches_in_a_discrete_time_SEIS_model (2000). Accessed 15 Apr 2015

Hu, Z, Teng, ZD, Jiang, H: Stability analysis in a class of discrete SIRS epidemic models. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 13, 2017-2033 (2012)

Hu, Z, Teng, ZD, Zhang, L: Stability and bifurcation analysis of a discrete predator-prey model with nonmonotonic functional response. Nonlinear Anal., Real World Appl. 12, 2356-2377 (2011)

Li, L, Sun, GQ, Jin, Z: Bifurcation and chaos in an epidemic model with nonlinear incidence rates. Appl. Math. Comput. 216, 1226-1234 (2010)

Aparicio, JP, Capurro, AF, Castillo-Chavez, C: Transmission and dynamics of tuberculosis on generalized households. J. Theor. Biol. 206, 327-341 (2000)

Blower, SM, McLean, AR, Porco, TC, Small, PM, Hopwell, PC: The intrinsic transmission dynamics of tuberculosis epidemics. Nat. Med. 1, 815-821 (1995)

Blower, SM, Small, PM, Hopwell, PC: Control strategies for tuberculosis epidemics: new models for old problems. Science 273, 497-500 (1996)

Castillo-Chavez, C, Feng, Z: To treat or not to treat: the case of tuberculosis. J. Math. Biol. 35, 629-656 (1997)

Castillo-Chavez, C, Feng, Z: Global stability of an age-structure model for TB and its application to optimal vaccination strategies. Math. Biosci. 151, 135-154 (1998)

Castillo-Chavez, C, Feng, Z: Mathematical models for the disease dynamics of tuberculosis. In: Arino, O, Axelrod, D, Kimmel, M (eds.) Advances in Mathematical Population Dynamics: Molecules, Cells and Man, pp. 629-656. World Scientific, Singapore (1998)

Feng, Z, Huang, W, Castillo-Chavez, C: On the role of variable latent periods in mathematical models for tuberculosis. J. Dyn. Differ. Equ. 2, 425-452 (2001)

Feng, Z, Castillo-Chavez, C, Capurro, AF: A model for tuberculosis with exogenous reinfection. Theor. Popul. Biol. 57, 235-247 (2000)

Kirschner, D: Dynamics of co-infection with M. tuberculosis and HIV-1. Theor. Popul. Biol. 55, 94-109 (1999)

Song, BJ, Castillo-Chavez, C: Tuberculosis control in the U.S.A.: A strategy to meet CDC’s goal. Department of Biometrics Technical Report Series BU-1562-M, Biometrics Department, Cornell University

Ziv, E, Daley, CL, Blower, SM: Early therapy for latent tuberculosis infection. Am. J. Epidemiol. 153, 381-385 (2001)

Zhao, XQ: Asymptotic behavior for asymptotically periodic semiflows with applications. Commun. Appl. Nonlinear Anal. 3, 43-66 (1996)

Allen, L, van den Driessche, P: The basic reproduction number in some discrete-time epidemic models. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 14, 1127-1147 (2008)

Elaydi, SN: An Introduction to Difference Equations. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer, New York (1999)

Elaydi, SN: Persistence in a discrete-time stage-structured epidemic model. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. 16, 73-103 (2010)

Zhao, XQ: Dynamical Systems in Population Biology. Springer, New York (2003)

National Technical Steering Group of the Epidemiological Sampling Survey for Tuberculosis, Office of the Nationwide Epidemiological Sampling Survey for Tuberculosis: On nationwide random survey for the epidemiology of tuberculosis in 2000. J. Chin. Antituberc. Assoc. 24, 65-108 (2002)

National Technical Steering Group of the Epidemiological Sampling Survey for Tuberculosis, Office of the Nationwide Epidemiological Sampling Survey for Tuberculosis: On nationwide random survey for the epidemiology of tuberculosis in 2010. J. Chin. Antituberc. Assoc. 34, 485-508 (2012)

Kumar, V, Abbas, AK, Fausto, N, Robbins, RN: Basic Pathology, 8th edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2007)

Bhunu, CP, Garira, W, Mukandavire, Z, Zimba, M: Tuberculosis transmission model with chemoprophylaxis and treatment. Bull. Math. Biol. 70, 1161-1191 (2008)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China Grant 11301314; by Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China Grant 2014JQ1025; by Backbone Youth Training Scheme of Shaanxi University of Science & Technology Grant XSG(4)014; and by National Nature Science Foundation of China Grant 11400856.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Authors’ contributions

HC is responsible for the model formulation, the calculation, and the proof. HT has done the simulation and the application. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, H., Tan, H. The discrete tuberculosis transmission model with treatment of latently infected individuals. Adv Differ Equ 2015, 165 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-015-0505-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-015-0505-8