Abstract

In this paper, firstly we will give the global construction of the mixed type extremal surface in Minkowski space along the analytic light-like line. Furthermore, we construct simply the local existence of extremal surface along a single light-like line.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

It is important to study the extremal surfaces in the theory of elementary particle physics, and it has also drawn attentions by mathematicians in geometrical analysis. In Minkowski space, the extremal surfaces include space-like type, time-like type, light-like type and mixed type. For time-like case, Milnor gave entire time-like minimal surfaces in the three-dimensional Minkowski space via a kind of Weierstrass representation [1]. Barbashov et al. studied the nonlinear differential equations describing in differential geometry the minimal surfaces in the pseudo-Euclidean space [2]. Kong et al. studied the equation of the relativistic string moving and the equation for the time-like extremal surfaces in the Minkowski space \(R^{1+n}\) [3, 4]. Liu and Zhou also gave the classical solutions to the initial boundary problem of time-like extremal surface [5, 6]. The time-like surfaces with vanishing mean curvature are constructed by [7, 8]. For the case of space-like extremal surfaces, we can see the classical papers of Calabi [9] and Cheng and Yau [10]. There are also important results for the purely space-like maximal surfaces [11, 12]. For the case of extremal surfaces of mixed type, we can also see the papers [12–15]. In addition, for the multidimensional cases, we refer to the papers by Lindblad [16], and Chae and Huh [17].

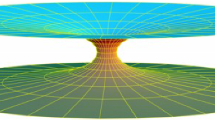

In this paper, firstly we consider the following mixed type extremal surface in Minkowski space:

We will give a sketch on constructing mixed extremal surfaces in 3-dimensional Minkowski space. The whole surface is presented with explicit formulas, starting from a plane analytic function of the arc length. Thus such surfaces are determined by a positive real analytic function.

In the next section we will discuss the characteristic of extremal surface along a light-like line. We denote by \(y = \phi(x, t)\) the surface in Minkowski space \(R^{1+(1+1)}\). Many examples of space-like maximal surfaces containing singular curves have been constructed [18–20]. In particular, if one gives a generic regular light-like curve, then there exists a zero mean curvature surface which changes its causal type across this curve from a space-like maximal surface to a time-like minimal surface [12, 21–23]. This can be constructed by Weierstrass-type representation formula. However, if L is a light-like line, the construction fails since the isothermal coordinates break down along the light-like singular points. Locally, such surfaces are the graph of a function \(y = \phi(x, t)\) satisfying (1). We call this and its graph the zero mean curvature equation and zero mean curvature surface, respectively. Gu [12] and Klyachin [24] gave several fundamental results on zero mean curvature surfaces which might change type.

2 The properties and representations of extremal surface

2.1 The general formulas and analytic function

Extremal surfaces (1) in Minkowski space are defined as surfaces with vanishing mean curvature \(H = 0\). And the surface is a graph \(y = \phi(t, x)\), we can rewrite the equation as the following type:

where

Equation (2) can be obtained by the variation problem

When \(1+q^{2}-p^{2}<0\) (>0), the surface is called time-like (space-like).

By the Legendre transformation, we have

Then we can get the linear dual equation of φ

which is hyperbolic (elliptic) when \(1+q^{2}-p^{2}<0\) (\(1+q^{2}-p^{2}>0\)).

It can be easily checked that the function

is a positively homogeneous harmonic function in \((u,v,w)\) of degree 1. If \(w\neq0\), Φ satisfies the linear wave equation

From the Legendre transformation, the extremal surfaces can be written in a parameter form:

If \(w\neq0\), t, x, z are functions of p, q and satisfy the mixed equation [25]

In the following, we can give the parametric expression of extremal surfaces. If \(1+q^{2}-p^{2}>0\), \(|q|>|p|\), then let

and let \(\lambda=\theta+\ln(\frac{1}{\rho}+\sqrt{1+\frac{1}{\rho^{2}}})\), \(\mu =\theta-\ln(\frac{1}{\rho}+\sqrt{1+\frac{1}{\rho^{2}}})\), we obtain the parametric expression of extremal surfaces

If \(1+q^{2}-p^{2}>0\), \(|q|<|p|\), we denote \(\rho=\sqrt{p^{2}-q^{2}} \), \(\theta=\operatorname{arcth}\frac{q}{p}\) and \(\lambda=\theta+\operatorname{ch}^{-1}\frac{1}{\rho}\), \(\mu=\theta-\operatorname{ch}^{-1}\frac {1}{\rho}\), we can get the parametric expression of extremal surfaces as follows:

On the other hand, if \(1+q^{2}-p^{2}<0\), we denote \(\rho=\sqrt {p^{2}-q^{2}} \), \(\theta=\operatorname{arcth}\frac{q}{p}\) and let

We can also get the parametric expression of extremal surfaces

Here \(f(\lambda)\) and \(g(\mu)\) are \(C^{1}\) functions with \(f(\lambda )\neq0\), \(g(\mu)\neq0\) and \(\tilde{f}(\lambda)\) is an analytic function. Thus we have (under the condition \(|q|<|p|\)) the following.

Theorem 1

The general expression of regular and dually regular time-like or space-like extremal surface in \(R^{1+(1+1)}\) is (12) or (13), respectively. If these two pieces can be matched regularly along the arc \(\rho=1\), \(a<\theta<b\), then the surface is analytic not only in the space-like part but also in the region \(a<\mu\leq\lambda<b\).

Remark 2.1

Under the assumption that \(|q|<|p|\), we can easily get the pieces of surfaces (12) and (13) connected regularly along arc \(\rho=1\), \(a<\theta<b\). Then \(\tilde{f}(\theta)\) must be a real analytic function and

2.2 Global construction of extremal surfaces

We are interested in the construction of whole mixed extremal surfaces. First we assume \(|q|<|p|\), it is convenient to start with a borderline of the space-like part and time-like part. The curve should be an analytic curve of null length

We construct the curve in the following way.

Let L be an analytic plane curve

We assume that the radius of curvature is always positive. Let τ be the angle between the tangent of L and x-axis. s can be expressed as an analytic function of τ in \((a,b)\) with \(\frac{ds}{d\tau}>0\). Then the borderline is

and we have

Actually, the curve is determined by the function \(s=s(\tau)\). Then the time-like surface extension from the borderline is

with \(\sigma=\operatorname{ch}^{-1}\frac{1}{\rho}\), \(\rho<1\). Using similar procedures, we can get the biggest extension. In particular, if s is an integral function such that \(s' \neq0\), the extension is valid for all \(\rho<1\) except for \(\rho=0\).

The surface can be extended further so that σ will be valued in \((\frac{\pi}{2},\pi)\). When \(\sigma\rightarrow\pi\), we can obtain a curve

This is another borderline on the surface or the surface is not of \(C^{2}\).

The space-like extension through the first borderline is

with \(\sigma= \arccos\frac{1}{\rho}\), \(\rho>1\). The extension can reach \(\sigma=\frac{\pi}{2}\) (\(\rho\rightarrow\infty\)), and the corresponding planes are parallel to the y-axis.

Then we can construct the extension through the second borderline in a similar way.

3 Extremal surface along a light-like line

Suppose that \(y = \phi(x,t) \in C^{\infty}\) is a solution of the extremal surface equation (1), and its graph contains a singular light-like line L. Without loss of generality, we can assume that L is included in \(\{(t, 0, t), t\in R\}\) and

where \(\alpha(t)\) and \(\beta(x, t)\) are \(C^{\infty}\)-functions. Denote

Note that \(B > 0\) (resp. \(B < 0\)) if and only if the graph is space-like (resp. time-like). Then we can get

Noting the definition of extremal surface, we have \(A_{xx}|_{x=0} = 0\). Then there exists a constant \(\mu\in R\) such that

Then \(B_{xx}|_{x=0} =-2\mu\). Using the Taylor extension, we can get the following.

Proposition 3.1

If \(\mu> 0\) (\(\mu< 0\)), then the graph of \(y = \phi(x, t)\) is time-like (space-like) on both sides of L.

In particular, the graph might change type across L from space-like to time-like only if the constant μ vanishes. However, even in this case, the graph might not change type. We can normalize the constant μ to be −1, 0, 1. We can also get the general solutions to (24) and local existence of extremal surfaces with a light-like line.

Theorem 2

For the following three cases of μ and the arbitrary constant C, we have

Then there exists a real analytic extremal surface in \(R^{1+(1+1)}\) locally containing a light-like line \((t, 0, t)\).

Lastly, we will give the solutions of extremal surface equations (1) with the following form:

where \(b_{k}(t)\) (\(k=1,2,\ldots\)) are \(C^{\infty}\)-functions. Without loss of generality, we assume that \(b_{0}(t)=t \), \(b_{1}(t)=0\). Using the same procedures as above, we have that there exists a real constant μ such that \(b_{2}(t)\) satisfies

Next we will derive the ordinary differential equations of \(b_{k}(t)\) for \(k\geq3\). We denote

Then we can obtain

where

for \(k\geq4\), and equation (1) can be rewritten as

By comparing the coefficients of \(x^{k}\), we can get that each \(b_{k}\) (\(k\geq3\)) satisfies the following ordinary differential equation:

where \(P_{3}=Q_{3}=R_{3}=0\) and \(P_{k}\), \(Q_{k}\) and \(R_{k}\) are as in (27) for \(k\geq4\). Note that \(P_{k}\), \(Q_{k}\) and \(R_{k}\) are written in the terms of \(b_{j}\) (\(j=1,2,\ldots,k-1\)) and their derivatives.

Finally, we consider the case that \(1+\phi_{x}^{2}-\phi_{t}^{2}\) changes sign across the light-like line \(\{t=t,x=0\}\). This case occurs only when \(\mu= 0\) as in (26). We can set \(b_{2}(t)=0\) (\(t\in R\)). Then

where c is a non-zero constant. Therefore, we have

In this situation, we will find a solution satisfying

Then (28) reduces to

and \(Q_{k}=R_{k}=0\) for \(4\leq k\leq6\), where the fact that \(b_{2}(t)=0\) has been extensively used. For example,

Then we can get the following result.

Theorem 3

For each positive number c, the formal power series solution \(\phi (x,t)\) uniquely determined by (32), (33), (34) and (35) gives a real analytic extremal surface on a neighborhood of \((x,t)=(0,0)\). In particular, there exists a non-trivial 1-parameter family of real analytic extremal surfaces, each of which changes type across a light-like line.

To prove Theorem 3, it is sufficient to show that for arbitrary positive constants \(c>0\) and \(\delta>0\), there exist positive constants \(n_{0}\), \(\theta_{0}\), and C such that

holds for \(k\geq n_{0}\). In fact, if (36) holds, then the series (30) converges uniformly over the rectangle \([-C^{-1},C^{-1}]\times[-\delta,\delta]\). The key assertion to prove (36) is the following.

Proposition 3.2

For each \(c>0\) and \(\delta>0\), we set

where τ is the positive constant such that

Then the function \(\{b_{l}(t)\} _{l\geq3}\) formally determined by the recursive formulas (32)-(35) satisfies the inequalities:

for any \(t\in[-\delta,\delta]\), where

We prove the proposition using induction on the number \(l\geq3\). If \(l=3\), then

hold, using that \(b_{3}(t)=3ct\), \(M^{0}=1\), and \(3^{*}=-1\). So we prove the assertion for \(l\geq4\). Since (40), (41) follow from (39) by integration, it is sufficient to show that (39) holds for each \(l\geq4\). (In fact, the most delicate case is \(l=4\). In this case \(l^{*}=-1/2\), and we can use the fact that \(\int_{0}^{t_{0}}1/\sqrt {t} \, dt\) for \(t_{0}>0\) converges.) From inequality (39) it follows that for each \(k\geq4\),

under the assumption that (39), (40) and (41) hold for all \(3\leq l\leq k-1\) (see in [26]). In fact, if (42) holds, (39) for \(l=k\) follows immediately. Then, by the initial condition (32) (cf. (31)), we have (40) and (41) for \(l=k\) by integration. Then we obtain the proof of Proposition 3.2.

In conclusion, we have finished the proof of Theorem 3 and given the local existence of extremal surfaces that change type beside a light-like line.

Change history

04 May 2018

The editors have retracted this article [1] as it contains sections that substantially overlap with the following articles [2–4]. The authors have not responded to any correspondence regarding this retraction.

References

Milnor, TK: Entire timelike minimal surfaces in \(E^{3, 1} \). Mich. Math. J. 37, 163-177 (1990)

Barbashov, BM, Nesterenko, VV, Chervyakov, AM: General solutions of nonlinear equations in the geometric theory of the relativistic string. Commun. Math. Phys. 84, 471-481 (1982)

Kong, DX, Sun, QY, Zhou, Y: The equation for time-like extremal surfaces in Minkowski space \(R^{n+2}\). J. Math. Phys. 47, 013503 (2006)

Kong, DX, Zhang, Q, Zhou, Q: The dynamics of relativistic strings moving in the Minkowski space \(R^{1+n}\). Commun. Math. Phys. 269, 153-174 (2007)

Liu, JL, Zhou, Y: Initial-boundary value problem for the equation of timelike extremal surfaces in Minkowski space. J. Math. Phys. 49, 043507 (2008)

Liu, JL, Zhou, Y: The initial-boundary value problem on a strip for the equation of timelike extremal surfaces. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 23(1-2), 381-397 (2009)

Hua, LK: A speech on partial differential equations of mixed type. J. China Univ. Sci. Technol., 1-27 (1965)

Busemann, A: Infinitesimale Kegelige uberschall-stromungenn. Schr. Dtsch. Akad. Luftfahrtforsch. 7B, 105-122 (1943)

Calabi, E: Examples of Bernstein problems for some nonlinear equations. Proc. Symp. Pure Math. 15, 223-230 (1970)

Cheng, SY, Yau, ST: Maximal space-like hypersurfaces in the Lorentz-Minkowski spaces. Ann. Math. 104, 407-419 (1976)

Courant, R, Hilbert, D: Methods of Mathematical Physics, vol. II. Interscience, New York (1962)

Gu, CH: The extremal surface in the 3-dimensional Minkowski space. Acta Math. Sin. New Ser. 1, 173-180 (1985)

Gu, CH: Complete extremal surfaces of mixed type in 3-dimensional Minkowski space. Chin. Ann. Math. 15, 385-400 (1994)

Gu, CH: Extremal surfaces of mixed type in Minkowski space \(R^{n+1}\). In: Variational Methods, pp. 283-296. Birkhäuser, Boston (1990)

Gu, CH: A global study of extremal surfaces in 3-dimensional Minkowski space. In: Differential Geometry and Differential Equations, pp. 26-33. Springer, Berlin (1987)

Lindblad, H: A remark on global existence for small initial data of the minimal surface equation in Minkowskian space time. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 132, 1095-1102 (2004)

Chae, D, Huh, H: Global existence for small initial data in the Born-Infeld equations. J. Math. Phys. 44, 6132-6139 (2003)

Estudillo, FJM, Romero, A: Generalized maximal surfaces in Lorentz-Minkowski space \(L^{3}\). Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 111, 515-524 (1992)

Kim, Y, Yang, SD: A family of maximal surfaces in Lorentz-Minkowski three-space. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 134, 3379-3390 (2006)

Umehara, M, Yamada, K: Maximal surfaces with singularities in Minkowski space. Hokkaido Math. J. 35, 13-40 (2006)

Fujimori, S, Kim, YW, Koh, S-E, Rossman, W, Shin, H, Umehara, M, Yamada, K, Yang, S-D: Zero mean curvature surfaces in Lorentz-Minkowski 3-space which change type across a light-like line (2012). arXiv:1211.4912

Kim, YW, Yang, SD: Prescribing singularities of maximal surfaces via a singular Björling representation formula. J. Geom. Phys. 57, 2167-2177 (2007)

Kim, Y-W, Koh, S-E, Shin, H-Y, Yang, S-D: Spacelike maximal surfaces, timelike minimal surfaces, and Björling representation formulae. J. Korean Math. Soc. 48, 1083-1100 (2011)

Klyachin, V: Zero mean curvature surfaces of mixed type in Minkowski space. Izv. Math. 67, 209-224 (2003)

Yuan, ZX: Born-Infeld equation and extremal surface. Acta Math. Sin. 2, 121-125 (1990) (in Chinese)

Fujimori, S, Kim, YW, Koh, S-E, Rossman, W, Shin, H, Takahashi, H, Umehara, M, Yamada, K, Yang, S-D: Zero mean curvature surfaces in \(L^{3}\) containing a light-like line. C. R. Math. 350, 975-978 (2012)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Jianli Liu for his suggestions. The third author was partially supported by Doctoral Fund of Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China (20133108120002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The authors declare that the work was realized in collaboration with the same responsibility. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The editors have retracted this article [1] as it contains sections that substantially overlap with the following articles [2, 3, 4]. The authors have not responded to any correspondence regarding this retraction.

1. Gao, R, Wang, F, Xhang, X, Wang, Y: Extremal surface with the light-like line in Minkowski space R1+(1+1). Boundary Value Problems. 58: 2017 (2017).

2. Gu C. A global study of extremal surfaces in 3-dimensional Minkowski space. Differential Geometry and Differential Equations. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol 1255. (1987).

3. Fujimori, S., Kim, Y.W., Koh, S.-E., Rossman, W., Shin, H., Umehara, M., Yamada, K. and Yang, S.-D., Zero mean curvature surfaces in Lorentz-Minkowski 3-space which change type across a light-like line, Osaka J. Math. 52 (2015), 285-297.

4. Fujimori, S, Kim, YW, Koh, S-E, Rossman, W, Shin, H, Takahashi, H, Umehara, M, Yamada, K, Yang, S-D: Zero mean curvature surfaces in L3 containing a light-like line. C. R. Math. 350, 975-978 (2012).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, R., Wang, F., Zhang, X. et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Extremal surface with the light-like line in Minkowski space \(R^{1+(1+1)}\) . Bound Value Probl 2017, 58 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-017-0786-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-017-0786-9