Abstract

Background

Interprofessional rehabilitation programs have demonstrated effectiveness at improving health-related quality of life, function, work abilities, and reducing pain, for patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP). However, the characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs vary widely across studies. Therefore, clarifying and describing key characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP will be valuable for future intervention design and implementation. This scoping review aims to identify and describe the key characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP.

Methods

Our scoping review will follow the framework developed by Arksey and O'Malley, further enhanced by Levac et al. and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). Electronic databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SCOPUS, PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library, will be searched to identify relevant published studies. Our scoping review will consider all primary source peer-reviewed published articles that evaluated interprofessional rehabilitation programs for adults with CLBP from all countries and any therapeutic settings.

The Covidence software will be used to remove duplicates, article screening, record the step-by-step selection process, and data extraction. The analysis will involve a descriptive numerical summary and narrative analysis. Data will be presented in graphical and tabular format based on the nature of the data.

Discussion

This scoping review is expected to provide a source of evidence for developing and implementing interprofessional rehabilitation programs in new settings or contexts. As such, this review will guide future research and provide key information to health professionals, researchers and policymakers interested in designing and implementing evidence and theory-informed interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP.

Trial registration

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a major public health problem globally [1, 2], incurring serious health system burdens and economic consequences on individuals, societies, and governments [3,4,5]. Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is defined as “a deep, aching, dull or burning pain or discomfort, localized below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds, with or without pain referred into leg persisting for a period of greater than 12 weeks” [6, 7]. In addition to pain and functional limitations, people with CLBP often experience anxiety, depression, and poor health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at higher rates than those without low back pain [8].

CLBP is among the leading cause of years lived with disabilities (YLDs) worldwide [1, 14]. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2017 estimates, the number of people with LBP increased from 377.5 million in 1990 to 577.0 million in 2017 [1, 9]. Hence, it remains a common problem in both high and low- and-middle-income countries [8, 10, 11]. The growing number of years lived with disability associated with LBP is being driven by increases in YLDs in low-and-middle-income countries [1, 9].

The complex, dynamic and multifactorial nature of CLBP makes it challenging to manage [12]. Increasingly, CLBP is well explained within a biopsychosocial model [13]. Interprofessional rehabilitation is recommended to address the multiple biological, psychological, and social factors associated with CLBP [14,15,16]. Recent studies indicate that an interprofessional rehabilitation program is effective in improving health-related quality of life, reducing pain, and improving the function and work participation of patients with CLBP [14,15,16]. However, currently, there is no single well-accepted description of an interprofessional rehabilitation program, and it is unclear what the optimal components of the interventions are, and which healthcare professionals shall be involved [6, 17]. Often, interprofessional rehabilitation programs have been defined as interventions consisting of at least two or more combinations of physical, psychological, social, vocational, and behavioral components delivered by a team of professionals with different backgrounds [15, 18]. The elements, duration, intensity, professionals involved, and descriptions of interprofessional rehabilitation programs vary widely across studies [18, 19], making it challenging to implement the evidence in new settings, especially in low- and middle-income countries. There is no evidence that an intervention component, duration, or setting of interprofessional rehabilitation programs described in the evaluated studies is superior to any of the other study treatment plan [20]. In addition, the health outcomes assessed were also heterogeneous, and there is no agreement on the measurement instrument [19].

Furthermore, heterogeneity in the contents, intensity of the interventions, and choice of outcomes may hamper comparisons between studies, knowledge synthesis, and conclusiveness of the evidence. To our knowledge, there is no published scoping review on descriptions and components of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP. A synthesis of the key characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs may facilitate the design and implementation of future interprofessional rehabilitation programs [21]. Hence, this scoping review aims to synthesize the descriptions and characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for people with CLBP evaluated in the literature.

The rationale for a scoping review

A scoping review is selected as an appropriate and rigorous evidence synthesis approach for reviewing a heterogeneous body of evidence and mapping rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area [22,23,24]. A preliminary search of the CINAHL (EBSCO), MEDLINE (Ovid), SCOPUS, Cochrane Library, and JBI Evidence Synthesis was performed in June 2022, and no current or underway scoping reviews on the topic were identified.

The evidence on the effectiveness of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for CLBP has been synthesized in systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [25, 26]. However, the characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs varied substantially across studies [17], and the systematic reviews have not synthesized the characteristics of each of the interprofessional rehabilitation programs evaluated. Hence, implementing the evidence from these systematic reviews in new settings is challenging. Further, systematic reviews of effectiveness have been limited to randomized control trials and have not included interprofessional rehabilitation programs for CLBP that have been evaluated through other study designs. Characteristics of the interprofessional rehabilitation programs that have been tailored to particular settings or contexts may be particularly beneficial for developing and evaluating interprofessional rehabilitation programs in new settings, including those with resource limitations.

This scoping review aims to provide a fulsome description of characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for CLBP evaluated in the peer-reviewed literature to support the development of interprofessional rehabilitation programs in new settings or contexts without limiting the search to particular trial designs. We anticipate the scoping review findings will provide a comprehensive overview of the characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs, including professions involved, program components or interventions, frequency, duration, and theoretical foundations of interprofessional rehabilitation programs.

Methods

Protocol design

Our scoping review will follow the framework developed by Arksey and O'Malley [22], which has been further enhanced by Levac et al. [27] and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [24]. The review process will include the following six stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies using an iterative team approach; (4) charting the data using the data extraction framework; (5) collate, summarize and report the results; and (6) consultation with key stakeholders [22, 27].

Our research team includes researchers from multiple disciplines, including team members with expertise in low back pain, interprofessional rehabilitation, and knowledge syntheses.

Stage 1: identifying the research questions

Through discussion with the research team, the overarching research question guiding this review is: what are the key characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP that have been evaluated in the peer-reviewed literature?

More specifically, this scoping review will try to address the following research questions:

-

1.

What types of interventions have been included in interprofessional rehabilitation programs used to treat patients with CLBP?

-

2.

How are interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP described across the studies?

-

3.

What is the duration and intensity/frequency of visits included in interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP?

-

4.

What health professionals have been involved in interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP?

-

5.

What health outcomes have been assessed in interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP?

-

6.

In what setting have interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP been provided?

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Eligibility criteria

The JBI updated guidance for scoping review [24] recommends including detailed inclusion criteria in the protocol, containing the PCC (Population, Concept, and Context) elements. Accordingly, we have developed the following inclusion and exclusion criteria to guide the search and help identify relevant studies (Table 1).

Types of sources

All primary published studies with any methodological approach (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed design research) will be the sources of evidence considered in this scoping study. The scoping review will include all studies that evaluate interprofessional rehabilitation programs for CLBP. The reference lists of systematic reviews and relevant studies identified through our search will be scanned to identify relevant primary research articles. However, we will not consider grey literature due to the time constraints we have in searching a large volume of grey literature, the lack of resources to manage a large volume of information found, and the inability to cover all grey literature repositories. As it is known, grey literature is less formally archived evidence, and searching will be time-consuming and inefficient. In addition, we wanted to include peer-reviewed high-quality evidence with a robust methodology and low risk of bias. In addition, opinion papers, all types of systematic reviews, and undergrad students’ theses not published in peer-reviewed journals will be excluded. In addition, commentaries, book reviews, and studies focusing on single-model interventions will also be excluded.

Search strategy

Electronic databases like MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SCOPUS, and Web of Science will be searched to identify relevant published studies.

A systematic approach will be followed to search for relevant articles using a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) and keywords related to an interprofessional rehabilitation program and CLBP. A Queen’s University librarian (AP) helps to refine the search strategy, keywords, and MeSH terms for each database. In addition, titles of articles from an initial search will also be checked to refine search terms. The following initial key search terms are developed by the research team and refined with the support of Queen’s University librarian (AP):

Key concepts

-

Concept 1: Chronic low back pain, Low Back Pain [MeSH Term], Low back ache, Back pain, Low backache, Lumbago, Mechanical low back pain, Lumbar pain

-

Concept 2: Multidisciplinary, Interdisciplinary, Interprofessional, Team, Transdisciplinary, Team-based, Collaborative, Multi-professional

-

Concept 3: Rehabilitation, Treatment, Management, Intervention, Approach, Care, Therapy

A comprehensive search strategy will be developed using Boolean operators and truncation to fit each database. First, each term identified under each concept will be entered into different databases to identify subject headings and similar keywords. Then, we will search one concept at a time, and terms within each concept will be connected with ‘OR’ Boolean operator. Finally, we will search all identified MeSH terms and keywords together in different databases. We will use the Boolean operator ‘AND’ between each concept. An iterative process will be applied to identify and develop a list of key search terms. The librarian (AP) in our research team will test relevant MeSH terms, keywords, and filters to enhance the sensitivity and specificity within each database. A sample search strategy for OVID MEDLINE and CINAHL databases is found in Appendix 1. The search strategy we use in different bibliographic databases will be available upon request from the authors.

The search will be limited to articles published in English due to the time and costs associated with translating articles published in other languages. However, there will be no date limits applied to our search.

Stage 3: study selection

The reference lists and abstracts of articles found from each database will be retrieved and imported into Covidence software [30]. The Covidence software will be used to remove duplicates and save references for further screening and data extraction process. Covidence was chosen to remove duplicates due to its accuracy, specificity and sensitivity to detect de-duplicates [31].

The study selection process will be conducted independently by two reviewers. Disagreement will be resolved by mutual consensus or by a third reviewer through a two-step process using Covidence software to record the step-by-step selection process according to our inclusion criteria. First, the two reviewers will independently review all the titles and abstracts of articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. As Levac et al. [27] suggested, the two reviewers will also meet part-way through the abstract review process to discuss any difficulties or confusion related to study selection and refine the search strategy. Hence, we will follow an iterative process and check whether the inclusion/exclusion criteria are followed consistently throughout the review process. Full-text articles will be reviewed when reviewers agree, based on the abstract, that the article is likely to be included and when it is difficult to decide based on the title and abstract. Next, the two reviewers will independently review the full articles of each selected for full-text review. We will compute Cohen’s kappa statistic to measure the inter-rater reliability (level of agreement) between the two reviewers [32]. A third reviewer will be consulted to decide the final inclusion when a disagreement happens between the two reviewers at either of the two stages of the screening process. Each reviewer will note the reasons when excluding the articles.

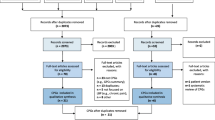

A flow chart will be prepared to show the study selection procedure at each stage of the review, including the reasons for exclusion. The study selection process will be reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram [33]. Since a scoping review methodology does not indicate the necessity for evaluating study quality and risk of bias assessment criteria [22, 24], we include all articles that fulfill the inclusion criteria. Hence, we will not perform a critical appraisal of included studies.

Stage 4: charting the data

Two reviewers will independently extract the data from articles included in the scoping review using the data charting framework in the software program, Covidence. A draft extraction form is provided (see Table 2). We will regularly update and refine the data charting framework and consider it an iterative process [24]. Any uncertainties related to the data extraction will be resolved through discussion between the research team. Moreover, regular discussions will be held between the research team to refine the framework.

Before the formal data extraction process, two reviewers will test the framework independently by extracting data from 10% of the included studies to ensure that their data extraction approach is uniform, and the framework is consistently used (reliability between extractors). We will only begin formal extraction when the percentage agreement is above 90% between the two reviewers. Inconsistency in extracted data between the two reviewers will be discussed until consensus is reached or resolved by a third reviewer [27].

Data to be extracted from relevant selected studies will include information about the author, year of publication, the objective of the study, study design, detailed descriptions of the interventions, country, settings, targeted population, and types of outcomes assessed (Table 2).

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The analysis will involve a descriptive numerical summary (e.g., frequency, percentage) and a narrative summary. First, we will apply a numerical description of the characteristics of included studies, including the overall number of studies included, years of publication, types of study designs, countries where studies were conducted, characteristics of the study population, detailed description of interventions, health professions involved in delivering the program, delivery mode, frequency and duration of the program, and settings of the intervention (Table 2).

The results will be reported through a thematic presentation and tables that align with the purpose of the scoping study. In addition, data will be presented in graphical representations such as pie charts and bar graphs when appropriate. Finally, we will discuss the meaning of the findings and implications for future research, policy, and clinical practice [27].

In this analysis, we will compare and describe interprofessional rehabilitation programs for people with CLBP evaluated across studies. The analysis will also explore the types of outcomes that have been reported in interprofessional rehabilitation programs for people with CLBP. In addition, we will try to show gaps in the descriptions and contents of an interprofessional rehabilitation program and indicate areas where further analysis is required. This scoping review will adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [33]. Any deviation from this protocol will be clearly detailed and justified in the full review report. The findings at this stage will be used to inform the stakeholders’ consultation process.

Stage 6: consultation with key stakeholders

Although Arksey and O'Malley (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005) suggest that consultation is an optional stage in conducting a scoping review, Levac et al. (Levac et al. 2010) argue that it should be a required component to add methodological rigour. Accordingly, we will conduct consultation with stakeholders to share preliminary results, to help identify potential meaning from the findings, obtain their feedback about the findings not revealed by the scoping study, and identify additional references about potentially relevant studies which offer extra value to a scoping study. Hence, we will use a preliminary finding to inform the consultation, which enables stakeholders to build on the evidence and offer a higher level of meaning and perspective to the preliminary findings.

Experts in CLBP, including healthcare providers and researchers in CLBP and interprofessional rehabilitation, will be consulted, thus offering important insights beyond what has been reported from the available evidence. We will conduct a focus group discussion (FGD) through a Zoom meeting with six to eight stakeholders. We will purposively recruit participants based on their expertise and lived experiences and send an invitation with a consent form through email. We will ask for any additional insights on how to interpret the findings of what has been reported in the literature and identify important gaps for future research. Focus groups will be video/audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using a descriptive qualitative approach.

Discussion

This review aims to synthesize the characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP evaluated in the literature. The characteristics described will include professions involved, program components or interventions, frequency, duration, the outcome evaluated, and theoretical foundations of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP evaluated in the literature to date. Synthesizing and describing the characteristics and components of interprofessional rehabilitation programs is expected to provide valuable evidence to inform new program development and implementation. For example, this review will constitute the initial step in a multistage research project to identify and develop an evidence and theory-informed interprofessional rehabilitation program for patients with CLBP that can be implemented in Ethiopia. This scoping review is expected to provide evidence for this, and other initiatives aimed at developing and implementing interprofessional rehabilitation programs in new settings or contexts. As such, this review will be beneficial in guiding future research and providing key information to health professionals, researchers and policymakers interested in designing and implementing evidence and theory-informed interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with CLBP.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- CLBP:

-

Chronic low back pain

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica Database

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Heading

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trial

- YLDs:

-

Years lived with disabilities

References

Wu A, March L, Zheng X, Huang J, Wang X, Zhao J, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Annals of translational medicine. 2020;8(6):299.

Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet (London, England). 2017;389(10070):736–47.

Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2008;8(1):8–20.

Maniadakis N, Gray A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain. 2000;84(1):95–103.

Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, Woolf A, Bain C, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):968–74.

Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J, Klaber-Moffett J, Kovacs F, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2006;15 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S192–300.

Joines JD. Chronic low back pain: progress in therapy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10(6):421–5.

Stewart Williams J, Ng N, Peltzer K, Yawson A, Biritwum R, Maximova T, et al. Risk Factors and Disability Associated with Low Back Pain in Older Adults in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Results from the WHO Study on Global AGEing and Adult Health (SAGE). PloS one. 2015;10(6):e0127880.

Wu A, March L, Zheng X, Huang J, Wang X, Zhao J, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Annals of translational medicine. 2020;8(6):299-.

Morris LD, Daniels KJ, Ganguli B, Louw QA. An update on the prevalence of low back pain in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):196.

Louw QA, Morris LD, Grimmer-Somers K. The prevalence of low back pain in Africa: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:105.

Cieza A, Stucki G, Weigl M, Disler P, Jäckel W, van der Linden S, et al. ICF Core Sets for low back pain. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2004(44 Suppl):69–74.

Waddell G. Biopsychosocial analysis of low back pain. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1992;6(3):523–57.

Gianola S, Andreano A, Castellini G, Moja L, Valsecchi MG. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: the need to present minimal important differences units in meta-analyses. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):91.

Marin TJ, Van Eerd D, Irvin E, Couban R, Koes BW, Malmivaara A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for subacute low back pain. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017;6(6):Cd002193.

Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, Smeets RJ, Ostelo RW, Guzman J, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014(9):Cd000963.

Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2001;322(7301):1511–6.

Saragiotto BT, de Almeida MO, Yamato TP, Maher CG. Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation for Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain. Phys Ther. 2016;96(6):759–63.

Chiarotto A, Boers M, Deyo RA, Buchbinder R, Corbin TP, Costa LOP, et al. Core outcome measurement instruments for clinical trials in nonspecific low back pain. Pain. 2018;159(3):481–95.

Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670–8.

Schmidt AM, Terkildsen Maindal H, Laurberg TB, Schiøttz-Christensen B, Ibsen C, Bak Gulstad K, et al. The Sano study: justification and detailed description of a multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation programme in patients with chronic low back pain. Clin Rehabil. 2018;32(11):1431–9.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Wickremasinghe D, Kuruvilla S, Mays N, Avan BI. Taking knowledge users’ knowledge needs into account in health: an evidence synthesis framework. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(4):527–37.

Peters M, Marnie C, Tricco A, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI evidence synthesis. 2020;18:2119–26.

Waddell G. The Back Pain Revolution. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier; 2004.

Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn A, Chiarotto A, Smeets R, Ostelo R, Guzman J, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;350: h444.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation science : IS. 2010;5:69.

Owen D Williamson, Cameron P. The Global Burden of Low Back Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain. https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/the-global-burden-of-low-back-pain/; 2021 9 July 2021.

Arnetz BB, Goetz CM, Arnetz JE, Sudan S, vanSchagen J, Piersma K, et al. Enhancing healthcare efficiency to achieve the Quadruple Aim: an exploratory study. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):362-.

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org. 2022.

McKeown S, Mir ZM. Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: evaluating the performance of different methods for de-duplicating references. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):38.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–82.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Funding

The MasterCard Foundation Scholarship Program financially supported this research work. The funder had no role in the design of this study, article searching, studies selection, reporting of results and decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SDW and JM contributed to the study design, defining the review question, developing preliminary search terms, and writing the protocol. SF, CD, and KAG contributed to refining the search terms, protocol write-up and review. AP contributed to identifying and testing appropriate search strategies, keywords, and MeSH terms that fit the different databases. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: Search strategy

Appendix 1: Search strategy

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL < 1946 to June 04, 2022 >

# | Query | Results from 4 June 2022 |

|---|---|---|

1 | exp Rehabilitation/ | 334,918 |

2 | exp Therapeutics/ | 4,937,770 |

3 | exp Pain Management/ | 38,802 |

4 | (Rehabilitat* or Therap* or manag* or treat* or intervention or approach* or care).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | 12,195,314 |

5 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 13,714,858 |

6 | exp Patient Care Team/ | 71,854 |

7 | exp Interdisciplinary Studies/ | 1,163 |

8 | (Interprofessional* or inter-professional* or Multidisciplinary or multidisciplinary or team or Interdisciplinary or inter-disciplinary or transdisciplinary or trans-disciplinary or collaborative or multi-professional).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | 419,846 |

9 | 6 or 7 or 8 | 419,859 |

10 | exp back pain/or exp low back pain/ | 42,434 |

11 | (backpain or "back pain" or Backache or "back ache" or lumbago).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] | 70,680 |

12 | 10 or 11 | 70,916 |

13 | 5 and 9 and 12 | 1,897 |

Box 1. Sample of search terms from the CINAHL database

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wami, S.D., Fasika, S., Donnelly, C. et al. Characteristics of interprofessional rehabilitation programs for patients with chronic low back pain evaluated in the literature: a scoping review protocol. Syst Rev 12, 105 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02275-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-023-02275-5