Abstract

Background

Despite evidence-based efficacy, mental health services are underutilized due to low rates of help-seeking, leaving unmet mental health needs a global concern. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has been applied to understand the help-seeking process and in the development of behavior change interventions. The aim of this scoping review was to map the literature on the TPB as applied to mental health help-seeking in adults aged >18 years.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted based on the methodology presented by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). Six databases (CINAHL, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, ProQuest Health and Medicine, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Web of Science) and two grey literature sources (OpenGrey, Google Scholar) were systematically searched in February 2018 and updated in March 2020. Studies that explicitly discussed the TPB in the context of mental health help-seeking were initially selected; only studies that explored formal help-seeking for mental health problems and were published in English were retained. Data were extracted using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Initially, 8898 records were identified. Of these, 49 met the selection criteria and were included: 32 were journal articles and 17 were theses. Forty-three papers reported on non-intervention studies and seven articles reported on TPB-based interventions. Most studies (n = 39) identified predictors of help-seeking intentions. Attitudes and perceived behavioral control were significant predictors of intentions in 35 and 34 studies, respectively. Subjective norms were a significant predictor of intentions in 23 studies. Few studies aimed to predict help-seeking behavior (n = 8). Intentions and perceived behavioral control were significant predictors of behavior in seven and six studies, respectively. Only six TPB-based interventions were identified, all used digital technology to influence help-seeking, with mixed results.

Conclusions

The present scoping review identified a considerable evidence base on the TPB for predicting mental health help-seeking intentions. Attitudes and perceived behavioral control were frequently found to be significant predictors of help-seeking intentions. Knowledge on the TPB for predicting mental health help-seeking behavior, and on TPB-based interventions, is limited. Thus, the role of the TPB in developing help-seeking interventions remains unclear. Recommendations are presented to address such research gaps and inform policy and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental health problems are a major public health concern. Recent prevalence estimates indicate 10.7% of the world’s population live with a mental health disorder, and the number of years lived with a mental health disorder has increased by 13.5% from 2007 to 2017, which is likely to be a reflection of increasing prevalence rates and greater life expectancy [1,2,3]. Associated with the rising prevalence rates of mental health problems is a high level of unmet mental health needs. Unmet mental health needs not only extend the period in which someone lives with the burden of ill mental health, but are also associated with greater levels of disability, reduced quality of life, and an increased likelihood of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [4, 5].

Pervasive unmet mental health needs have been reported in prominent and large-scale studies of mental health such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Mental Health Surveys and are reflected in low rates of service utilization [6,7,8,9]. For example, results of the World Mental Health Surveys conducted across 21 countries revealed only 27.6% of people with anxiety disorders received treatment over the course of one year, and less than one in 10 received adequate treatment [10]. People in low- and middle-income countries were the least likely to receive treatment (13.1%). Furthermore, national data from Australia and Canada indicate a little over half of the people who experienced emotional distress in 2013 and 2016 received treatment; however, many people (37% in Australia and 30% in Canada) reported that they did not want treatment [11].

Individual and social factors, such as perceived need for treatment, poor mental health literacy, and low rates of help-seeking have been shown to influence rates of service utilization. Researchers have noted that many people with mental health problems go undiagnosed and untreated, often due to a lack of knowledge about mental health disorders and their treatments, as well as a lack of help-seeking for mental health problems [12, 13]. This has led to a widely recognized mental health treatment gap, whereby more individuals are diagnosed with mental health problems than those who receive treatment [14, 15]. This treatment gap continues to exist even with the growing evidence base on effective mental health treatments.

The literature indicates that despite the effectiveness of evidence-based mental health treatments, most people do not seek help, or delay seeking help, which has significant personal, social, and economic costs [14, 16]. There are many factors that influence help-seeking including stigma, attitudes, knowledge, financial resources, perceived need, and structural barriers/facilitators [12, 17,18,19]. Understanding these factors and addressing the disparity between the need for mental health services and their use are critical to understanding and addressing mental health outcomes. Still, most of the research on mental health help-seeking has been exploratory and devoid of a theoretical orientation, which has been identified as a gap in the body of knowledge. A clear theoretical framework would greatly improve our ability to understand, explain, predict, and address maladaptive behaviors such as refraining from seeking professional mental health support.

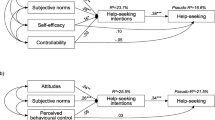

In recent years, researchers have attempted to address this gap [20,21,22], and a number of theories have been applied to mental health help-seeking [23]. One such theory is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). The TPB is an extension of Ajzen and Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and suggests people make conscious decisions to act, or not act, based on their attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [24]. The theory posits that attitudes towards a behavior influence a person’s plan or intention to act, and subsequently, the action or behavior itself [25]. Subjective norms, defined as perceived social pressures from significant others to perform a behavior, also influence a person’s intentions and behavior [26]. Perceived behavioral control, which is the perceived opportunities, skills, and resources needed to perform a behavior, can influence behavior directly or indirectly as it affects intentions [24]. The inclusion of perceived behavioral control as an antecedent to intentions and behavior is the main difference between the TPB and the TRA. By considering the role of perceived behavioral control, the TPB includes non-motivational factors that influence behavior, thereby overcoming criticisms of the TRA [26, 27]. Thus, the TPB proposes that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence behavioral intentions, which predict behavior [24].

The utility of the TPB to explain factors that contribute to decision-making, and how behavior change occurs, is thought to be particularly useful in understanding mental health issues, the help-seeking process, and developing interventions to facilitate mental health behavior change [28,29,30]. Whilst there is no commonly accepted definition of professional help-seeking, Cornally and Mccarthy [31] defined help-seeking as “a problem focused, planned behavior, involving interpersonal interaction with a selected health-care professional”. Seeking help from a professional, also known as formal help-seeking, involves seeking help from professional sources who can provide appropriate care [16]. Seeking help from a professional is considered optimal for the receipt of evidence-based treatments [23, 32]. The conceptualization of help-seeking as a planned behavior aligns well with the TPB, as it suggests seeking help involves a conscious or planned decision to seek or not seek support. There is also evidence supporting attitudes and intentions as influential to mental health help-seeking behavior, further substantiating the relevance of the TPB in this area [33]. Applying theories that encompass attitudes and intentions when investigating behavior, such as the TPB, is recommended by scholars and has been a major focus of research across fields [34].

Whilst there is no universally accepted theory or model in the area of mental health help-seeking [23], the body of research applying the TPB to understand mental health help-seeking continues to gain momentum, and the TPB has been favored as the most common approach to frame help-seeking in the literature [16]. Studies on the TPB have identified predictors of mental health help-seeking intentions as well as behavior. For example, Tomczyk et al. [29] found attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy (a component of perceived behavioral control), significantly influence intentions, and intentions significantly predict behavior, among people with untreated depressive symptoms in Germany. Moreover, Zorrilla et al. [35] explored predictors of help-seeking intentions among young adults in the USA and found attitudes was a strong, significant predictor of help-seeking intention for mental health services, followed by perceived behavioral control and subjective norms. Conversely, Bohon et al. [36] found partial support for the influence of TPB variables on help-seeking, with attitudes and perceived behavioral control significantly predictive of intentions to seek help, but not subjective norms.

There is a need to synthesize what is known about the TPB in the context of mental health help-seeking, to facilitate the identification of factors related to mental health help-seeking, which may provide viable targets for intervention to encourage mental health service utilization and potentially reduce the treatment gap. Recent research has attempted to improve rates of mental health help-seeking through TPB-based interventions [37,38,39], however these are yet to be reviewed. It is important to understand what efforts have been made to improve mental health help-seeking to progress the effectiveness of interventions and inform future directions.

The aim of the current scoping review was to map the literature on the TPB when applied to mental health help-seeking. Given the favorable results of the TPB in the health field, and logical expansion of the TPB to mental health help-seeking, this theory provides an important evidence base from which mental health help-seeking can be understood and improved. A scoping review allowed the identification of different types and sources of evidence on this topic, as well as gaps in them, which limit our understanding. The purpose of this scoping review was to:

-

1)

Identify how the TPB has been applied to mental health help-seeking

-

2)

Identify and summarize the theoretical factors, which influence help-seeking intentions and behavior

-

3)

Explore the current state of knowledge on TPB-based interventions designed to improve mental health help-seeking

-

4)

Highlight how this understanding can inform future research and practice on mental health help-seeking in adult populations.

Methods

The current scoping review was based on the methodology outlined by Arksey and O’Malley [40]. Arksey and O’Malley proposed a five-stage process, which includes (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. This process was followed, and the scoping review is reported based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (see Additional file 1) [41].

Review protocol

The scoping review protocol was drafted using Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage process and was published on the Open Science Framework on 9th November 2017 (https://osf.io/73c5a/).

Identifying the research question

The research question for this scoping review was: What is known about the application of the TPB to mental health help-seeking in adults?

Criteria for study inclusion

Table 1 summarizes the study eligibility criteria.

Types of studies

All studies, which explicitly discussed the TPB in the context of mental health help-seeking, independently of the TRA, were included in the current review. Studies that utilized mediation, moderation, and extended models of the TPB were included only if they examined all variables in the TPB model, and these variables were examined independently (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intentions and, where applicable, behavior). For the purposes of this study, we defined traditional TPB models as models which included only the aforementioned TPB variables and extended TPB models as those which included any additional predictor(s).

Intervention studies were included if they utilized the TPB model in the design and development of the intervention. Editorials, opinion pieces, and conference abstracts were excluded. Qualitative studies were also excluded as these tended to be formative research, which use the TPB as an exploratory framework rather than apply the TPB constructs to mental health help-seeking.

Participants

This review included papers focused on adults aged >18 years. Samples with and without mental health problems were included, as well as samples restricted to specific sociodemographic criteria (such as age, gender, and occupation). Populations with cognitive deficits such as dementia, intellectual disabilities, and head injuries were excluded, as a person’s cognitive ability directly affects their capacity to seek help as well as process the TPB variables. Studies specific to people diagnosed with schizophrenia, drug users, and survivors of cancer were also excluded due to the cognitive impairments often found in these populations resulting from their treatments or drug use.

Concepts

Only papers focused on formal mental health help-seeking were included in the current review. Formal help-seeking has been defined as seeking help from professional sources who can provide appropriate care [16]. In the context of mental health help-seeking, a professional source may include a primary health care provider (general practitioner, nurse, medical specialist) or mental health specialist (psychologist, social worker, counselor, psychiatrist). Formal mental health help-seeking may be face-to-face or online (e.g., e-counseling) as long as it was from a professional source. Self-help programs and resources were excluded, and papers which did not distinguish between formal and informal sources of support were also excluded.

Studies were included if the reason for seeking help was for mental health problems or concerns. For the purposes of the current review, a mental health problem included any symptoms of emotional distress or psychological disturbance, to ensure all studies relevant to mental health were encompassed. The mental health problem did not have to be formally diagnosed as a mental disorder or meet established criteria for a mental disorder.

Some mental health problems such as substance abuse and eating disorders have been considered health-related behaviors in previous research [42, 43]. In the present review, these conditions were excluded, as our aim was to examine how the TPB has been applied to mental health problems beyond the traditional application of the TPB to health-related behaviors.

Additionally, studies which focused on secondary help-seeking (seeking help for someone else such as a peer, family member, or friend) were excluded as we sought self-agency over help-seeking behavior, in line with the TPB assertion that behavior must be under volitional control [24].

Measures

Standardized quantitative measures of the TPB are scarce, and therefore, all questionnaires and tools that measure TPB variables were included.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes founded in the TPB framework were (1) attitudes: attitudes toward seeking help for mental health problems; (2) subjective norms: beliefs about whether others approve or disapprove of help-seeking; (3) perceived behavioral control: beliefs about one’s own ability to seek help for mental health problems; and (4) help-seeking intentions: conscious decision to seek or not seek help.

The secondary outcome was help-seeking behaviors, defined as actual help-seeking from a health professional.

Identifying relevant studies

Searches were conducted across six databases (CINAHL, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, ProQuest Health and Medicine, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, and Web of Science) and two gray literature sources (OpenGrey and Google Scholar). Only papers published in English were included. The searches were run during February 2018 and updated in March 2020. With the help of an experienced subject librarian, keywords were selected, which allowed for breadth of coverage (see Table 2).

The above search strategy was used for each database search, and keywords from this search strategy were used to search the gray literature sources. Multiple combinations of the keywords were used to conduct the Google Scholar searches, and the first 50 pages (representing 1000 results) were screened using Google search engines relevancy ranking to order the results [44]. Reference list searches were also conducted from articles selected for inclusion to identify other relevant studies, which may have been absent in the electronic searches.

Study selection

All titles and abstracts retrieved through the literature searches were reviewed independently by two researchers to identify studies that met the inclusion criteria. The reviewers met during the title and abstract screening and at the conclusion of this stage to discuss and resolve conflicts regarding the inclusion of articles. The inclusion criteria at the title and abstract level were limited to any paper that utilized the TPB or any of its primary variables (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control) in relation to mental health problems. Studies excluded at this stage were those including children under the age of 18 exclusively, people with cognitive deficits, and studies not published in English. The covidence systematic review platform was used for title and abstract screening [45].

Once the relevant studies had been selected, the full-text was retrieved and read independently by two researchers to determine eligibility for inclusion, based on the criteria described above. A third senior reviewer was consulted to resolve conflicts regarding the inclusion of articles, and a final decision was reached once a consensus was achieved.

Charting the data

A standard data charting form was developed and pilot-tested in Microsoft Excel before data extraction. Data collected from each study were organized according to key information: basic descriptors (title, first author, year of publication, publication type, country), eligibility information (aim/purpose of the paper, reason for seeking help, source of help), study population (population group, mental health status, sample size, setting, method of recruitment, sociodemographic information), research methods (study design, measures used, analysis, intervention details if applicable), primary and secondary outcome measures (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intentions, behavior), and description of key findings.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

Descriptive tables were used to outline the key information from each paper. Based on the content of the articles and the present research question, the studies were organized according to non-interventions and interventions. Tables were used to highlight the pertinent information from the non-intervention and intervention studies according to our review objectives.

Results

A PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Fig. 1, which outlines the process of selecting studies. There were 8898 records identified through the literature searches. After the removal of duplicates, 5626 records were screened for eligibility. There were 5436 records excluded at the title and abstract stage, 143 articles excluded after full-text screening and three articles excluded after data extraction. The reasons for exclusion are provided in Fig. 1. A further 5 articles were identified through reference list searches and screened. This process resulted in the inclusion of 49 articles.

Characteristics of studies

The 49 articles that were chosen were published between 1998 and 2020; 32 (65%) were journal articles and 17 (35%) were theses. Of these, 42 (86%) were non-intervention studies, six (12%) were intervention studies, and one paper (2%) reported on both cross-sectional data and an intervention (Fig. 2).

Most studies were conducted in North America (n = 27, 55%), followed by Europe (n = 9, 19%), Asia (n = 8, 16%), Oceania (n = 4, 8%), and Africa (n = 1, 2%). In terms of the populations, most targeted college students (n studies = 16, 33%; n participants = 6048), followed by community samples (n studies = 12, 25%; n participants = 7305), both students and community samples (n studies = 1, 2%; n students = 320; n community adults = 208), armed forces or emergency service workers (n studies = 8, 16%; n participants = 1910), older adults (n studies = 2, 4%; n participants = 568), and other specific populations (n studies = 10, 20%; n participants = 3137).

Most studies included all participants with and without symptoms of mental health problems (n studies = 42, 86%; n participants = 17371), three studies (6%; n participants = 1542) only included participants with psychological symptomatology, two studies (4%; n participants = 160) targeted people who screened positive for a mental disorder, one study (2%; n participants = 400) included dysphoric individuals only, and an intervention design paper (n studies = 1, 2%; n participants = 23) only included young adults with experience in seeking help for mental health issues.

TPB-based non-intervention studies

Forty-three articles reported on non-intervention studies [21, 29, 35, 36, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83]. Of these, 28 (65%) were journal articles and 15 (35%) were theses. A summary of the final selected non-intervention articles is given in Additional file 2, Supplementary Table 1.

Two journal articles reported on the same sample [77, 79], and one thesis reported pre-intervention cross-sectional data and intervention data and thus was included in both sections [58]. One study reported on post-intervention data only and was included under non-intervention studies as the intervention was not based on the TPB [62]. The results of the study are not reported due to the study design.

Most of the non-intervention studies were conducted in North America (n = 23, 53%), followed by Europe (n = 9, 21%), Asia (n = 8, 19%), Oceania (n = 2, 5%), and Africa (n studies = 1, 2%). The most commonly targeted populations were students (n studies = 14, 33%; n participants = 5588), followed by armed forces or emergency service workers (n studies = 7, 16%; n participants = 1900) and community samples (n studies = 10, 23%; n participants = 7231).

Of the 43 non-intervention papers, 38 were cross-sectional studies that aimed to identify predictors of mental health help-seeking intentions and/or behaviors. Five of the cross-sectional papers included a psychometric study or elicitation study, which designed and/or evaluated measures to assess TPB variables, for use in the main cross-sectional study [36, 50, 53, 54, 59]. Three papers were solely psychometric evaluations, which examined the validity and reliability of attitudinal mental health help-seeking scales. Two centered on the reliability and validity of the Inventory of Attitudes towards Seeking Mental Health Services (IASMHS) [49, 84]. The third paper developed and tested the Mental Help-Seeking Attitudes Scale (MHSAS) [76]. One psychometric study also reported on predictors of help-seeking intentions [84].

In addition, one paper was an experimental between-group design, which aimed to influence intentions to seek help for depression through evoking positive emotions using nostalgic messages [62], and one paper presented baseline data from a randomized controlled trial examining students’ intentions to seek help and actual counselling usage [58].

The type of mental health problem was rarely defined in the literature, most commonly referred to as a psychological problem or mental health problem/concern (n studies = 21, 49%). Other terms used included psychological stress/distress, personal and/or emotional problems, psychological difficulties, mental health conditions, persistent issues, and common concerns. Some studies gave examples of mental health problems, for example, Mo and Mak [21] used the term mental health problems and provided a definition to include low mood, tense, anxious, and problems sleeping. Stecker et al. [55] used the term mental health concerns and defined these to include major depressive disorder, panic disorder, generalized anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and/or alcohol abuse disorder. Some studies presented a list of symptoms or problems such as depressed mood, anxiety, relationship difficulties, personal concerns, memory loss, and alcohol or drug abuse [50, 51, 59].

Depression was the only mental health problem to be examined independently, with eight studies (19%) focusing only on help-seeking for depression, and one study (2%) focusing on depression and suicidal thoughts [35, 36, 48, 53, 58, 60, 62, 72]. These studies included all participants irrespective of their mental health status, with the exception of one paper which included only dysphoric individuals [60]. Additionally, three studies (7%) explored help-seeking for suicidality as well as other emotional or mental health problems [54, 66, 80].

As only formal mental health help-seeking was included, most studies reported the source of help as mental health services, psychological/psychiatric help, mental health professional, or a combination of these terms (n studies = 27, 63%). Additional terminology included counseling (n studies = 7, 17%), treatment (n studies = 5, 12%), cyber-counseling (n studies = 1, 2%), therapy for depression (n studies = 1, 2%), psychotherapy (n studies = 1, 2%), and prison psychologist (n studies = 1, 2%). Of the studies that defined the type of service, common examples included social workers, counselors, psychologists, and psychiatrists. Six studies (14%) also specified physicians/general practitioners within their definition [49, 55, 57, 67, 71, 75].

Factors which influence help-seeking intentions and behavior

The theoretical factors, which predict help-seeking intentions and behavior, are summarized in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Some studies (n = 13, 33%) used traditional models of the TPB to explore help-seeking, whereby only the original TPB variables (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intentions, and where applicable, behavior) were included in the model. Other studies (n = 19, 49%) used extended models of the TPB, in which the original TPB variables and additional variables were included in the model (either as predictors or control variables), to identify further predictors of mental health help-seeking relevant to the population. Seven studies (18%) explored both traditional and extended models.

Overall, 39 studies identified predictors of mental health help-seeking; 31 studies identified predictors of mental health help-seeking intentions only, and eight studies identified predictors of intentions and behavior.

From the 39 studies that identified predictors of mental health help-seeking intentions, attitudes was a significant predictor of intentions in 35 (90%) studies, perceived behavioral control was a significant predictor of intentions in 34 (87%) studies, and subjective norms was a significant predictor of intentions in 23 (59%) studies. The variance in mental health help-seeking intentions explained by the TPB ranged from 7 to 93% for both the traditional and extended models.

There were eight articles that examined factors, which influence mental health help-seeking behavior. Seven of the eight articles (88%) found intentions to be a significant predictor of mental health help-seeking behavior, and six of the eight (75%) articles found perceived behavioral control to be a significant predictor of behavior. Two of the articles (25%), which did not support perceived behavioral control as a predictor of help-seeking behavior only examined one component of this construct, control factors, which may account for the insignificant findings [55, 64]. Furthermore, two articles (25%) found perceived behavioral control to be a significant predictor of behavior in the traditional TPB model, but not when the model was extended to include other variables [47, 83].

An additional paper examined help-seeking behavior but did not utilize the full TPB model [60]. In this paper, intentions were found to be a significant direct predictor of prospective help-seeking, and direct relationships were also found between attitudes and prospective help-seeking, and subjective norms and current help-seeking.

Overall, the variance in mental health help-seeking behavior explained by the TPB ranged from 3 to 61% for the traditional models and 10 to 63% for the extended models.

TPB-based interventions

Seven articles were identified on TPB-based interventions; four were journal articles and three were theses [30, 37,38,39, 58, 85, 86]. The seven articles comprised six unique interventions, which used the TPB model to improve intentions or behavior to seek professional help. A summary of the final selected intervention articles is given in Additional file 2, Supplementary Table 2.

Three of the interventions were evaluated in randomized controlled trials, two were evaluated in pre-post studies, and one was assessed using a randomized post-test-only design. All six interventions used digital technology: two interventions were short videos on seeking counseling services, three were web-based tools, and one was a theory-guided multimedia presentation. The target population were mainly young adults (n studies = 5, n participants = 704), one study targeted USA war veterans (n participants = 10), and one study focused on adolescent mothers with a mean age of 18 (n participants = 289).

The findings from each study were mixed. One study demonstrated improvements in mental health help-seeking intentions and behavior after intervention. Logsdon et al. [39] employed a pre-post design to evaluate an Internet-based depression intervention encouraging adolescent mothers to seek depression treatment and found a statistically significant increase in both intentions to seek treatment and actually receiving treatment over time in the intervention group compared to the control group. Another study that designed a web-based psychoeducational tool for USA veterans reported an increase in willingness to consider mental health treatment post-intervention [30].

Two studies, both using video interventions on attending counseling, demonstrated significant improvements in all three TPB predictor variables (attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control) immediately after the intervention [58, 85]. Chang [58] also conducted a follow-up and found sustained improvements in subjective norms and perceived behavioral control at 4-weeks post-intervention. In both studies, changes in predictor variables did not translate to improvements in intentions or behavior. Furthermore, Lindsley’s [86] guided multimedia presentation on treatment seeking reported findings consistent with overall improvements in TPB predictor variables after intervention; however, this declined over time and no differences between the experimental and control group were found. Finally, an online navigation tool for young adults designed to match participants with appropriate services did not demonstrate improvements in help-seeking intentions; changes in other TPB variables were not assessed [37, 38].

Discussion

The current scoping review mapped existing literature on the TPB when applied to mental health help-seeking. Of the 49 articles included, the earliest paper identified was published in 1998, with a rise in the number of studies since 2008, indicating growing interest in this field. Most studies were conducted in western countries (North America and Europe), with college students and community samples the most common populations targeted. Participants with and without mental health problems were typically included, which aligns with an early intervention approach to mental health care [87].

This body of research typically applied the TPB to predict mental health help-seeking intentions (n = 39). Most studies found the TPB accounted for a large amount of variance in intentions; however, the range in variance explained was large. Of the theoretical factors, which influence mental health help-seeking intentions, attitudes and perceived behavioral control were frequently found to be significant predictors of help-seeking intentions, and subjective norms were found to be a significant predictor in more than half of the studies. This indicates that across population groups, a person’s favorable or unfavorable evaluation towards using mental health-related services, and their perceived resources, skills, and opportunities to access services, influence their intentions to seek help. For example, the belief that seeing a mental health professional will be helpful, and beliefs regarding potential costs of mental health consultations, influence help-seeking intentions [53]. The influence of subjective norms on intentions, that is, perceived social pressures to seek help, was less consistent, which may be due to differences in cultural norms and beliefs. For example, western cultures are typically individualistic and therefore, people from these cultures may be more motivated to act according to their own goals and beliefs [88]. In the present review, we found subjective norms were not statistically significant predictors of help-seeking intentions in some studies conducted in the USA [36, 55]. In studies conducted in non-western cultures such as South Asia and among Chinese populations, social pressures were found to significantly predict help-seeking intentions [21, 73]. This may be reflective of the collectivistic nature of these societies, which traditionally encourage interconnectedness with others [88].

Indeed, cultural factors such as race, ethnicity, and religion have been shown to influence help-seeking intentions and behavior. For example, mental health problems are commonly stigmatized in Chinese societies, which hinders people’s intentions to seek help for fear of social rejection [50, 64]. In some extended and modified models of the TPB, variables such as adherence to Asian values, shame/izzat, and a Strong Black Woman ideal were included and were shown to significantly predict help-seeking intentions [22, 47, 72]. Some authors have advocated for the use of extended models of the TPB to better explain help-seeking intentions and behavior [89, 90]. In the present scoping review, most non-intervention studies (67%) used extended models or both traditional and extended models to conceptualize help-seeking intentions; however, the variances explained by these models were comparable to traditional TPB models. Thus, factors that influence help-seeking intentions beyond the theoretical factors in the TPB require further investigation.

Fewer studies applied the TPB to predict mental health help-seeking behavior (n = 8). Intentions and perceived behavioral control were significant predictors of behavior in most of these studies, supporting the TPB framework. Of the studies that did predict help-seeking behavior, past and/or present behaviors were commonly used as the outcome. We only located three studies, which explored the ability of the TPB to predict future behavior [29, 55, 75]. This is a key gap in the evidence related to predicting whether people would seek help for mental health problems if a future need arose. Whilst studies have found past behavior to have been a good indicator of future behavior, this is not always the case [24]. Additionally, there is a widely recognized intention–behavior gap, where positive intentions are not always antecedent for actual behavior [91]. Thus, there exists an important opportunity to develop TPB models for predicting future behavior, to identify groups who are in need and yet are less likely than other populations to seek help, and to enable targeted interventions to address their needs as well as increase help-seeking behaviors among them.

The current state of knowledge on TPB-based interventions for mental health help-seeking is in its infancy, with few studies published, all within the last decade. It is both difficult and premature to draw conclusions as to the role of the TPB as a framework for developing behavior change interventions for mental health help-seeking, due to the variation in predictor variables examined, lack of diversity in populations, and limited ways in which the interventions were delivered. Of the seven studies we located on TPB-based interventions to improve mental health help-seeking, six used digital technology, mostly to target young adults. This is of concern, given recommendations from researchers to use the TPB to promote behavioral change across populations, and the various approaches which can be trialed to facilitate the greatest change in behavior, e.g., persuasive communications, face-to-face discussions, and observational modeling [42, 92, 93]. There is a need and room for the development and evaluation of TPB-based interventions using different modes of delivery and targeting both community samples and at-risk populations, which may be effective in promoting help-seeking and facilitating service utilization.

There is also space for the TPB to be applied across subgroups who experience disparities in service provision, to explain intentions and behavior towards mental health service utilization; however, this has been largely overlooked in studies to date. Background factors such as age, race, ethnicity, and social class are associated with different behavioral beliefs, behavioral intentions, and prevalence rates of behaviors [94]. Such factors can be incorporated into the TPB model to identify inequities in health and health-related behaviors and guide the allocation of resources to better meet the needs of diverse communities who have differential access to care [94]. For example, people from culturally and linguistically diverse groups are less likely to engage mental health services than members of the wider population, due to a lack of knowledge of services and how to access them, communication barriers, financial barriers, racism, and culturally insensitive practices [95,96,97]. Moreover, attitudes towards and beliefs about mental health problems and treatments among diverse groups may differ from dominant Western approaches, and access to culturally appropriate care is often limited [98]. The TPB can be applied to identify background factors that influence help-seeking, and attitudes, norms, and control beliefs associated with help-seeking among racial and ethnic minority groups, providing insight into service access and use. Such research is important to accurately address the needs of marginalized populations and promote inclusive practices.

Implications for future research and practice

The current scoping review provides a resource for researchers and practitioners to understand mental health help-seeking through the lens of TPB. Prominent research gaps are highlighted in Fig. 3.

There is scope for a number of systematic reviews to determine the most significant predictors of mental health help-seeking intentions and behavior, which can be used as target areas for intervention. Systematic reviewers may wish to focus their investigations on determining the key TPB-based predictors of mental health help-seeking among student samples, given the predominance of studies on this population. There is also scope to conduct a systematic review on methods for measuring TPB variables due to the diversity in quantitative tools used to assess these constructs. This will enable more accurate measurement of these variables and greater ability to compare findings. An investigation of the most reliable evidence for the effects of TPB-based interventions on mental health help-seeking intentions and behaviors is also warranted. Such reviews could provide stakeholders a sound basis for their decisions on how to assess and improve mental health help-seeking.

Strengths and limitations

By employing a scoping review methodology and a systematic approach to the selection of studies, we conducted a comprehensive and structured review of the literature in line with current recommendations for good practice [99]. This clear structure makes the current results more accessible to stakeholders interested in applying the findings to inform policy and practice [40]. It is still possible that we did not locate all relevant studies or misclassified relevant papers.

Whilst we aimed to include only those studies relevant to adults, defined as people aged 18 years and over, there were three studies which did not define the age of participants [65, 66, 68]. As the sample in Miller [65] comprised lawyers, it is safe to assume that the age of participants was >18 years. In Rathbone (2014) and Mills (2010), however, the target samples were college students, and it is, therefore, possible that the mean age of participants in these studies was <18 years [66, 68]. As we cannot be certain, these three studies were included in this review to ensure we did not falsely exclude relevant papers.

A further limitation is the paucity of TPB-based standardized questionnaires on mental health help-seeking, which restricts our confidence in the accurate measurement of TPB variables. Many authors have created their own measures or adapted previous measures to fit their study contexts [21, 53, 78]. Additionally, validated tools such as the Attitude Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale (ATSPPHS) and IASMHS have been constructed and applied to mental health help-seeking, but do not necessarily reflect the true nature of the TPB. For example, the ATSPPHS has been widely used as a measure of help-seeking attitudes; however, this tool precedes the TPB and its development was not guided by any explicit theoretical framework [49, 76]. The IASMHS was designed to improve upon this measure by including items, which directly target the TPB predictor variables; however, the three subscales of the IASMHS only loosely reflect the TPB and contain other constructs such as mental health literacy, self-disclosure, avoidance coping, or self-concept clarity [49, 76]. We, therefore, cannot detect whether intentions to seek help were influenced by the components of the TPB or the overlapping or related constructs inherent in this measure. Furthermore, studies that used the IASMHS but did not reference the TPB would not have been identified by our searches but may add to our understanding of mental health help-seeking within a TPB framework. More consistency is needed in the assessment of TPB variables to strengthen the conclusions drawn about the explanatory role of the TPB in the present context.

Additionally, we applied a strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, which may have resulted in the exclusion of closely related studies. We chose this approach to strengthen our understanding of the original TPB framework, without modifications.

Conclusions

As the TPB is one of the most prominent theories in the social and behavioral sciences, the current scoping review was prudent to improve our understanding of the role of the TPB in explaining mental health help-seeking among adults. With the increase in effective psychological treatments, there is a pressing need for researchers and clinicians to promote engagement with mental health services to alleviate some of the personal and societal costs associated with ill mental health.

As a result of mapping the evidence base, we have identified a considerable body of research on the TPB for predicting mental health help-seeking intentions. Attitudes and perceived behavioral control, in particular, appear to be well-cited factors influencing people’s intentions to seek or not seek help. Less attention was paid to help-seeking behavior; however, among the eight studies that explored help-seeking behavior, intentions and perceived behavioral control were found to be significant predictors of help-seeking behavior, which further supports the TPB in this context. The evidence base for TPB-based interventions to improve mental health help-seeking is in its early stages, and there appears to be a number of gaps in the literature that limit our understanding of the applicability of the TPB in this context and warrant further research.

An important line of future enquiry could be to utilize the theoretical framework of the TPB to find ways to increase help-seeking behavior to improve mental health outcomes. A particular focus should be paid to groups at-risk of mental health problems, such as veterans, people with chronic illnesses, and immigrants, to reduce the personal and societal burden of unmet mental health needs. The current scoping review provides a broad map of the evidence related to mental health help-seeking, which can inform future research, policy, and practice.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- ATSPPHS:

-

Attitude Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale

- IASMHS:

-

Inventory of Attitudes towards Seeking Mental Health Services

- MHSAS:

-

Mental Help-Seeking Attitudes Scale

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews

- TPB:

-

Theory of Planned Behavior

- TRA:

-

Theory of Reasoned Action

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

Ritchie H, Roser M. Mental health. Our World in Data; 2018. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health

Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Degenhardt L, Feigin V, Vos T. The global burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders: an analysis from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):1–14.

Ali MM, Lackey S, Mutter R, McKeon R. The relationship between perceived unmet mental health care needs and suicidal ideation and attempt. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res. 2018;45(5):709–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0856-z.

Alonso J, Codony M, Kovess V, Angermeyer MC, Katz SJ, Haro JM, et al. Population level of unmet need for mental healthcare in Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(4):299–306 Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0007125000171776/type/journal_article.

Ishikawa H, Kawakami N, Kessler RC. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence, severity and unmet need for treatment of common mental disorders in Japan: results from the final dataset of World Mental Health Japan Survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25(3):217–29.

Roll JM, Kennedy J, Tran M, Howell D. Disparities in unmet need for mental health services in the United States, 1997-2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(1):80–2.

Tran LD, Ponce NA. Who gets needed mental health care? Use of mental health services among adults with mental health need in California. Californian J Health Promot. 2017;15(1):36–45.

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Worldwide use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders: results from 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–50 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673607614147.

Alonso J, Liu Z, Evans-Lacko S, Sadikova E, Sampson N, Chatterji S, et al. Treatment gap for anxiety disorders is global: results of the World Mental Health Surveys in 21 countries. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(3):195–208.

Corscadden L, Callander EJ, Topp SM. Who experiences unmet need for mental health services and what other barriers to accessing health care do they face? Findings from Australia and Canada. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019;34(2):761–72.

Bonabi H, Müller M, Ajdacic-Gross V, Eisele J, Rodgers S, Seifritz E, et al. Mental health literacy, attitudes to help seeking, and perceived need as predictors of mental health service use: a longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204(4):321–4.

Tay JL, Tay YF, Klainin-Yobas P. Mental health literacy levels. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(5):757–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.04.007.

Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858–66.

Wainberg ML, Scorza P, Shultz JM, Helpman L, Mootz JJ, Johnson KA, et al. Challenges and opportunities in global mental health: a research-to-practice perspective. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(5):28–44 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11920-017-0780-z.

Rickwood D, Thomas K, Bradford S. Help-seeking measures in mental health: a rapid review. New South Wales: The Sax Institute; 2012. Available from: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/02_Help-seeking-measures-in-mental-health.pdf.

Schnyder N, Panczak R, Groth N, Schultze-Lutter F. Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(4):261–8.

Staiger T, Waldmann T, Rüsch N, Krumm S. Barriers and facilitators of help-seeking among unemployed persons with mental health problems: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-1997-6.

Umubyeyi A, Mogren I, Ntaganira J, Krantz G. Help-seeking behaviours, barriers to care and self-efficacy for seeking mental health care: a population-based study in Rwanda. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(1):81–92.

Britt TW, Bennett EA, Crabtree M, Haugh C, Oliver K, Mcfadden A, et al. The theory of planned behavior and reserve component veteran treatment seeking. Mil Psychol. 2011;23(1):82–96.

Mo PKH, Mak WWS. Help-seeking for mental health problems among Chinese: the application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(8):675–84.

Pilkington A, Msetfi RM, Watson R. Factors affecting intention to access psychological services amongst British Muslims of South Asian origin. Ment Heal Relig Cult. 2012;15(1):1–22.

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Brewer JL. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(81):1–12.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1980.

Conner M, Sparks P. Theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting Health Behaviour. 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2005. p. 170–222.

Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality and behavior. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 1988.

Conner M, Heywood-everett S. Addressing mental health problems with the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Health Med. 1998;3(1):87–95.

Tomczyk S, Schomerus G, Stolzenburg S, Muehlan H, Schmidt S. Ready, willing and able? An investigation of the theory of planned behaviour in help-seeking for a community sample with current untreated depressive symptoms. Prev Sci. 2020;21(6):749–60.

Whealin JM, Kuhn E, Pietrzak RH. Applying behavior change theory to technology promoting veteran mental health care seeking. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(4):486–94.

Cornally N, Mccarthy G. Help-seeking behaviour: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(3):280–8.

Brown JSL, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L, Henderson MJ, Hatch SL, Hotopf M. Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):1–15.

Ten Have M, De Graaf R, Ormel J, Vilagut G, Kovess V, Alonso J. Are attitudes towards mental health help-seeking associated with service use? Results from the European study of epidemiology of mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(2):153–63.

Marcinkowski T, Reid A. Reviews of research on the attitude–behavior relationship and their implications for future environmental education research. Environ Educ Res. 2019;25(4):459–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1634237.

Zorrilla MM, Modeste N, Gleason PC, Sealy DA, Banta JE, Trieu SL. Depression and help-seeking intention among young adults: the theory of planned behavior. Am J Health Educ. 2019;50(4):236–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2019.1616014.

Bohon LM, Cotter KA, Kravitz RL, Cello PC, Fernandez y Garcia E. The theory of planned behavior as it predicts potential intention to seek mental health services for depression among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2016;64(8):593–603.

Kauer S, Buhagiar K, Sanci L. Facilitating mental health help seeking in young adults: the underlying theory and development of an online navigation tool. Adv Ment Health. 2017;15(1):71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/18387357.2016.1237856.

Kauer SD, Buhagiar K, Blake V, Cotton S, Sanci L. Facilitating mental health help-seeking by young adults with a dedicated online program: a feasibility study of Link. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7):1–12.

Logsdon MC, Myers J, Rushton J, Gregg JL, Josephson AM, Davis DW, et al. Efficacy of an internet-based depression intervention to improve rates of treatment in Adolescent mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21(3):273–85.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Ajzen I, Manstead ASR. Changing health-related behaviours: an approach based on the theory of planned behaviour. In: Hewstone M, Schut HAW, De Wit JBF, Van Den Bos K, Stroeb MS, editors. The scope of social psychology: theory and applications. London: Psychology Press; 2007. p. 43–64.

Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11(2):87–98.

Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, Leatherdale ST. Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Syst Rev. 2015;4(138):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0.

Covidence. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne: Veritas Health Innovation; n.d. Available from: www.covidence.org.

Aldalaykeh M, Al-Hammouri MM, Rababah J. Predictors of mental health services help-seeking behavior among university students. Cogent Psychol. 2019;6(1):1–10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1660520.

Li W, Denson LA, Dorstyn DS. Help-seeking intentions and behaviors among mainland Chinese college students: integrating the theory of planned behavior and behavioral model of health services use. Int J Adv Couns. 2017;39(2):125–48.

Logsdon MC, Morrison D, Myers JA, Capps J, Masterson KM. Intention to seek depression treatment in Latina immigrant mothers. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39(11):962–6 Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01612840.2018.1479905.

Mackenzie CS, Knox VJ, Gekoski WL, Macaulay HL. An adaptation and extension of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2004;34(11):2410–33.

Mak HW, Davis JM. The application of the theory of planned behavior to help-seeking intention in a Chinese society. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1501–15.

Mesidor JK, Sly KF. Mental health help-seeking intentions among international and African American college students: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Int Stud. 2014;4(2):137–49.

Pumpuang W, Seeherunwong A, Vongsirimas N. Factors predicting intention among nursing students to seek professional psychological help. Pacific Rim Int J Nurs Res. 2018;22(3):200–11 Available from: https://he02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/PRIJNR/article/view/89827.

Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Attitudes that determine willingness to seek psychiatric help for depression: a representative population survey applying the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Med. 2009;39(11):1855–65.

Skogstad P, Deane FP, Spicer J. Social-cognitive determinants of help-seeking for mental health problems among prison inmates. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2006;16(1):43–59 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/cbm.54.

Stecker T, Fortney J, Hamilton F, Sherbourne CD, Ajzen I. Engagement in mental health treatment among veterans returning from Iraq. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:45–9.

Teo T, Shi W, Huang F, Hoi CKW. Intergenerational differences in the intention to use psychological cybercounseling: a Chinese case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(8):1615–22.

Westerhof GJ, Maessen M, De Bruijn R, Smets B. Intentions to seek (preventive) psychological help among older adults: an application of the theory of planned behaviour. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(3):317–22.

Chang KF. An intervention to increase counseling service usage among female college students. (Publication No. 3540311) [Doctoral dissertation, University of California]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2012.

Clansy CD. The relationship between mental health ministries in the African Amercian church and professional mental health help-seeking. (Publication No. 9822860) [Doctoral dissertation, Saint Louis University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 1998.

Farmer CS. Understanding poor help-seeking rates for major depressive disorder. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Exeter]. Open Research Exeter; 2013. Available from: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/14620

Hamidi E. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict international students’ help-seeking intentions and behaviors. [Masters thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University]. Virginia Tech Electronic Theses and Dissertations. http://hdl.handle.net/10919/48593; 2014.

Hussain SA. Bittersweet nature of nostalgia and its impact on depression related help-seeking. (Publication No. 10843189) [Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global; 2018.

Jarvis J. If we build it will they come? The impact of attitudes, subjective social norms, and perceived behavioral control on help-seeking intentions. (Publication No. 3049630) [Doctoral dissertation, Long Island University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2002.

Lee AM-S. Understanding the help-seeking process among second generation Chinese Canadians using the theory of planned behaviour: what is the role of culture? [Doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa]. University of Ottawa digital repository; 2016. https://doi.org/10.20381/ruor-5103.

Miller JR. Attitudes and beliefs lawyers have about seeking professional mental health services. (Publication No. 3141098) [Doctoral dissertation, Marquette University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2004.

Mills JL. Does the theory of planned behavior predict intentions to seek help for suicidality? (Publication No. 3461849) [Doctoral dissertation, Marshall University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2010.

O’Flaherty R. Factors affecting psychological help-seeking in men. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick]. Warwick Research Archive Portal http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/96714; 2017.

Rathbone J. Understanding psychological help-seeking behaviour: the application of the theory of planned behaviour to medical professionals in training. (Publication No. 10137130) [Doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2014.

Seyala ND. Older adults’ intentions to utilize mental health services: the effects of cohort membership. (Publication No. 3490144) [Doctoral dissertation, Ball State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2011.

Taylor RE. Explaining intentions to seek mental health services among Black Canadians. (Publication No. 10843421) [Masters thesis, University of Windsor]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2018.

Walther AT. Factors affecting intentions to seek professional mental health services. (Publication No. MQ73099) [Masters thesis, Queen’s University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2002.

Woods KC. The strong black woman archetype and intentions to seek therapy for depression: a cultural application of the theory of planned behavior. (Publication No. 3599504) [Doctoral dissertation, Michigan State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.; 2013.

Chandrasekara WS. Help seeking attitudes towards mental health problems and actual help seeking behavior. Res J Soc Sci Manag. 2016;5(9):45–53 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342926067_Help_Seeking_Attitudes_towards_Mental_Health_Problems_and_Actual_Help_Seeking_Behavior.

Cuyler M, Guerrero L. Mental health help-seeking intentions and organizational climate among military members. Mil Psychol. 2019;31(4):315–25.

Damghanian M, Alijanzadeh M. Theory of planned behavior, self-stigma, and perceived barriers explains the behavior of seeking mental health services for people at risk of affective disorders. Soc Heal Behav. 2018;1(2):54–61 Available from: https://www.shbonweb.com/article.asp?issn=2589-9767;year=2018;volume=1;issue=2;spage=54;epage=61;aulast=Damghanian.

Hammer JH, Parent MC, Spiker DA. Mental help seeking attitudes scale (MHSAS): development, reliability, validity, and comparison with the ATSPPH-SF and IASMHS-PO. J Couns Psychol. 2018;65(1):74–85.

Hyland P, Boduszek D, Shevlin M, Adamson G. Investigating the latent structure of the theory of planned behavior and its effectiveness in explaining intentions to participate in counseling among a sample of police officers. J Police Crim Psychol. 2012;27(2):129–40.

Hess TR, Tracey TJG. Psychological help-seeking intention among college students across three problem areas. J Couns Dev. 2013;91(3):321–30.

Hyland PE, McLaughlin CG, Boduszek D, Prentice GR. Intentions to participate in counselling among front-line, at-risk Irish government employees: an application of the theory of planned behaviour. Br J Guid Couns. 2012;40(3):279–99.

Karras E, Stokes CM, Warfield SC, Elder H, Stephens B, Bossarte RM. The use of theory-based formative research to design suicide prevention messaging for U.S. veterans in midlife. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(6):1016–24 Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1090198118769344.

Kgathi C, Pheko MM. Application of theory of planned behaviour on Batswana men’s psychological help-seeking behaviours. J Couns Dev High Educ South Africa. 2011;2(1):63–75 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288653630_Application_of_Theory_of_Planned_Behaviour_on_Batswana_Men’s_Psychological_Help-seeking_Behaviours.

Lee JEC, Sudom KA, Fikretoglu D, Blais AR, Beatty E. Mental health services use intentions among Canadian military recruits. Mil Psychol. 2016;28(6):498–505.

Li W, Denson LA, Dorstyn DS. Understanding Australian university students’ mental health help-seeking: an empirical and theoretical investigation. Aust J Psychol. 2018;70(1):30–40.

Hyland P, Boduszek D, Dhingra K, Shevlin M, Maguire R, Morley K. A test of the inventory of attitudes towards seeking mental health services. Br J Guid Couns. 2015;43(4):397–412.

Hartong JM. Help seeking and the theory of planned behavior in college students: experiment and model testing. (Publication No. 3490121) [Doctoral dissertation, Ball State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global; 2011.

Lindsley TW. A multimedia intervention to increase the likelihood that university students in need will utilize counseling services. (Publication No. 3606867) [Doctoral dissertation, Utah State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global; 2013.

Wilson CJ, Bushnell JA, Caputi P. Early access and help seeking: practice implications and new initiatives. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(Suppl 1):34–9.

Cohen AB, Wu MS, Miller J. Religion and culture: individualism and collectivism in the east and west. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2016;47(9):1236–49.

Conner M. Extending not retiring the theory of planned behaviour: a commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(2):141–5.

Gollwitzer PM, Oettingen G. From studying the determinants of action to analysing its regulation: a commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(2):146–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.919511.

Sheeran P, Webb TL. The intention–behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503–18.

Fife-Schaw C, Sheeran P, Norman P. Simulating behaviour change interventions based on the theory of planned behaviour: impacts on intention and action. Br J Soc Psychol. 2007;46(1):43–68.

Ajzen I. Behavioral interventions based on the theory of planned behavior. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst; 2006. Available from: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.intervention.pdf.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press; 2010.

Wohler Y, Dantas JA. Barriers accessing mental health services among culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) immigrant women in Australia: Policy implications. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(3):697–701 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10903-016-0402-6.

Le CB, Trinh NH, Li Z, Hou SSY, Progovac AM. Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004-2012. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(1):9–16.

Thomson MS, Chaze F, George U, Guruge S. Improving immigrant populations’ access to mental health services in Canada: a review of barriers and recommendations. J Immigr Minor Heal. 2015;17(6):1895–905 Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10903-015-0175-3.

Cross W, Singh C. Dual vulnerabilities: mental illness in a culturally and linguistically diverse society. Contemp Nurse. 2012;42(2):156–66.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Beron Wei Zhong Tan for his assistance during the initial stages of the project.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CA under the supervison of EG and NS designed the study and drafted the study protocol. CA conducted the systematic searches of databases and gray literature. CA and NS screened and extracted the articles. CA prepared the draft manuscript. EG and NS technically edited the manuscript. The author(s) have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Additional file 2: Table S1

. Characteristics of studies – non-interventions. Table S2. Characteristics of studies – interventions.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, C., Gringart, E. & Strobel, N. Explaining adults’ mental health help-seeking through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: a scoping review. Syst Rev 11, 160 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02034-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02034-y